(Arlington, Massachusetts, August 8, 1892 – August 26, 1918, near Bapaume).1

Henry Bradley Frost was from a family with deep roots in Massachusetts and New England. An ancestor, Edmond Frost, was among the early Puritan settlers in Massachusetts, having emigrated in 1635; on Frost’s mother’s side, the Bradleys can be traced back to an Isaac Bradley of Branford, Connecticut, whose presence there is attested as early as 1667.2 Frost was the youngest of three children and the only son of an Arlington farmer, Frank Clifton Frost, and his wife, Martha Ann (née Bradley) Frost.3

After graduating from high school in Arlington, Frost entered Dartmouth in 1910, graduating with an A.B. degree in 1914. He travelled that summer to England; on his return in September, he pursued studies at Dartmouth’s Thayer School and received a degree in civil engineering in 1915. His thesis, “Plans and specifications of a private drive on the estate of Frank C. Frost, Arlington, Mass.” is preserved in the Dartmouth archives.4 His draft registration card indicates that in 1917 he was working for Swift and Company in Boston and that he had served for eight months in the Iowa National Guard. Another source indicates that he had worked for Swift in Illinois and Iowa in 1916 and 1917 and, that in the summer of 1916, at the time of the Mexican Punitive Expedition, he was stationed with the Iowa National Guard (Company G, 3rd Iowa Infantry) near Brownsville, Texas, on the Mexican border.5

In the summer of 1917 Frost started ground school at M.I.T., graduating August 25, 1917.6 Along with about a third of his M.I.T. classmates, he was selected for training in Italy, and he was thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania, departing New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departing Halifax as part of a convoy on September 21, 1917. After an uneventful Atlantic crossing the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, and the men proceeded not to Italy, but to Oxford, where they repeated ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. There is a photo of him alongside Harold Kidder Bulkley, Donald Elsworth Carlton, and Walter Chalaire, taken apparently in front of the building which served as the dormitory for the majority of the second Oxford detachment men.

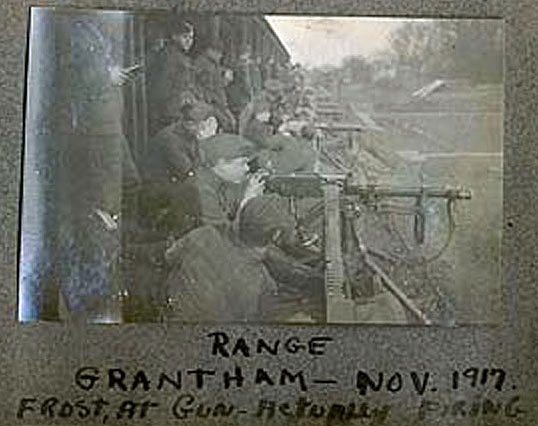

On November 3, 1917, Frost travelled with most of the detachment to Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gun school. There he shared a hut with four men from his M.I.T. ground school class (Harvard DeHart Castle, Edward Addison Griffiths, Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, and Melville Folsom Webber) as well as Parr Hooper, Edward Russell Moore, and Thomas M. Nial.7

Frost was one of the fifty men from the second Oxford detachment chosen in mid-November to leave Grantham for flying schools. On November 19, 1917, he, along with Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, Hamilton, Joseph Ralph Sandford, and Hugh Douglas Stier, set off for No. 14 Training Squadron near Tadcaster in West Yorkshire; a picture of them captioned “The Big Five at Tad” is preserved in Milnor’s photo album.8 The training planes used at No. 14 were Maurice Farman Shorthorns (“Rumpties”). Frost, along with Sandford and Hamilton, was assigned to A flight. Assuming Frost’s progress resembled Milnor’s and Stier’s in C flight, he would have had his first (dual) flight before Thanksgiving and would have flown solo in the first part of December.8a

In mid-December 1917 Frost was reassigned to No. 81 Squadron (a training squadron, despite its name) at Scampton a few miles north of Lincoln in Lincolnshire. Murton Llewellyn Campbell, who arrived there December 29, 1917, wrote in his diary that day: “Frost is also in the 81st, been here about two weeks but had no flying as yet.” Nonetheless, and despite winter weather, Frost evidently progressed rapidly. William Ludwig Deetjen, who had gone to flying school at Stamford directly from Oxford, noted in his diary entry for January 18, 1918, that “Frost landed here [Waddington] in an Avro the other day. That is progress and he was at Grantham at that.” If Campbell’s experience is any guide, Frost went on from Avros to Sopwith Pups, and then to Sopwith Camels while at Scampton; his otherwise uninformative R.A.F. service record indicates that he graduated (passed R.F.C. Central Flying School exams and tests) on January 22, 1918.9

About a month later Frost was posted to Turnberry in Scotland where there was a school of aerial gunnery; Murton Campbell’s diary entry for February 18, 1918, reads in part: “Got orders this afternoon to go to Turnberry together with Andy and Frosty tomorrow morning.” And for March 2, 1918: “Landis, Frost, Ortmayer and myself together with several R.F.C. men went to Ayr on the 5:01. . . . We are billeted in Middleton House on the opposite side of town from the airdrome.”10 Ayr, just up the coast from Turnberry, was the site of an R.F.C. school of aerial fighting where pilots trained on various planes, including Camels.

In the meantime, in a cable dated February 14, 1918, Pershing had forwarded to Washington the recommendation that Frost, Murton Campbell, Stier, and Earl William Sweeney be commissioned as first lieutenants; the confirming cable is dated February 21, 1918.11 There was always some delay between the confirming cable and when the news trickled down to the man in question, and not until March 3, 1918, does Murton Campbell record in his diary that “the surprise of my existence came this evening in the form of a commission. I had just about given up hopes of such coming through for some time. Evidently Frosty and I were the first to get our bars in the original Italian detachment.”12

The entry for April 7, 1918, in War Birds lists Frost as among those “going out on Camels to regular British squadrons just as if they were R.F.C. pilots.” Frost apparently left England for No. 2 A.S.D. on April 3, 1918, and then joined No. 210 Squadron R.A.F., a Camel squadron, at Treizennes, about ten miles southeast of Saint Omer, on April 7, 1918.13 No. 210 “was engaged in ground attack duties, helping to stop the German offensive” and in “offensive patrols and bomber escort missions over Belgium”; additionally 210 provided “fighter cover . . . to monitors off the Belgian coast.”14 It moved frequently during the time Frost was assigned to it, from Treizennes to Liettres and then to Saint Omer at the end of April and, on May 30, 1918, to Sainte-Marie-Cappel.15

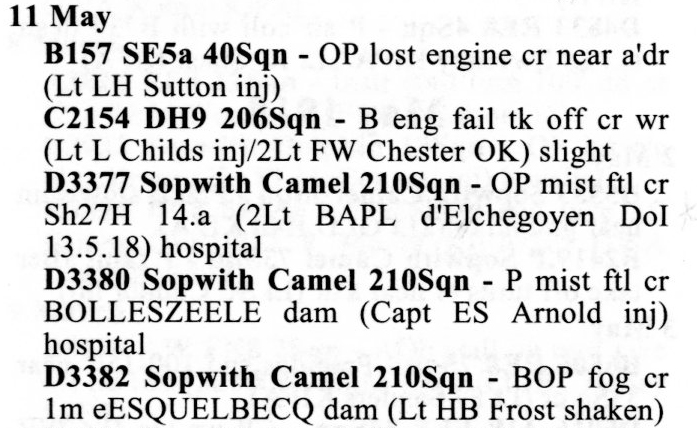

While the squadron was still at St. Omer, on May 11, 1918, Frost, taking part in a bombing and offensive patrol, crashed a mile east of Esquelbecq in fog; his Camel (D3382) was damaged, and he was “shaken” and sustained a “contusion wound under left eye. Not serious.” He returned to duty on May 16, 1918.16

Three weeks later, on about June 20, 1918, Frost was at Petite Synthe near Dunkirk, assigned to the U.S. 17th Aero Squadron, a pursuit squadron flying Camels; he was joined by fellow second Oxford detachment members Hamilton, Weston Whitney Goodnow, and Murton Campbell.17 The 17th, along with the 148th, was American in personnel, but stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until late in the war. Frost was appointed deputy commander of C Flight (Hamilton was commander).18 After about three weeks of getting to know their equipment and their territory while working on formation flying (and crossing the lines, despite R.A.F. regulations), the 17th flew their first offensive patrol on July 15, 1918; they began escorting DH.9 bombers into German occupied territory on July 20, 1918.19 Frost served as commander of C flight on this day, as Hamilton was on leave.20

During late July and early August 1918 plans for an attack on the large enemy aerodrome at Varsenare, a few miles west of Bruges, were being made, and the 17th Aero joined R.A.F. squadrons in this successful mission on August 13, 1918. In early August, Frost took his allotted two weeks leave from the squadron, and this would account for his name being absent from accounts of the raid.21

On August 17, 1918, the 17th moved south from Petite Synthe to Auxi-le-Château northwest of Doullens.22 As part of the British drive towards Cambrai, they were again to escort R.A.F. bombers, but also to do their own bombing and strafing. On August 24, 1918, Frost participated in the raid during which Hamilton went missing. Frost, flying Camel C141 at about 1500 feet dropped bombs and fired rounds at transport near Quéant (about ten miles west of Cambrai); he went out on a further bombing mission later that day.23

Frost was informally appointed commander of C flight to replace Hamilton pending approval from headquarters. On the first sortie the day after Hamilton had gone missing, Samuel Baltz Eckert, the C.O. of the 17th, led the flight; he gave the leadership to Frost when the squadron went over the lines in the evening.24

In the afternoon of the next day (August 26, 1918), despite bad weather and strong east winds, and apparently unaware that the Germans had moved in air squadrons to support their troop withdrawal, “the colonel of the wing took it upon himself to send [planes of the 148th Squadron] out on another ground straffing expedition.”25 On learning that pilots of the 148th had gotten into trouble east of Bapaume, planes from the 17th, including Camel C141 flown by Frost, went out to assist them and ended up in a trap, severely outnumbered by enemy aircraft. Henshaw records that Frost was “seen in combat with 5 Fokker DVIIs e[ast of] Bapaume over Sh57C.E. 5-30pm. . . other E[nemy] A[ircraft] then joined fighting. . . .”26 Squadron historian Frederick Mortimer Clapp’s operations summary for that day reads: “1st Lieuts. William D. Tipton; Henry B. Frost; 2nd Lieuts. Robert M. Todd; Harry H. Jackson Jr.; Howard P. Bittinger and 1st Lieut. Laurence ‘missing’ from O[ffensive] P[atrol].”27

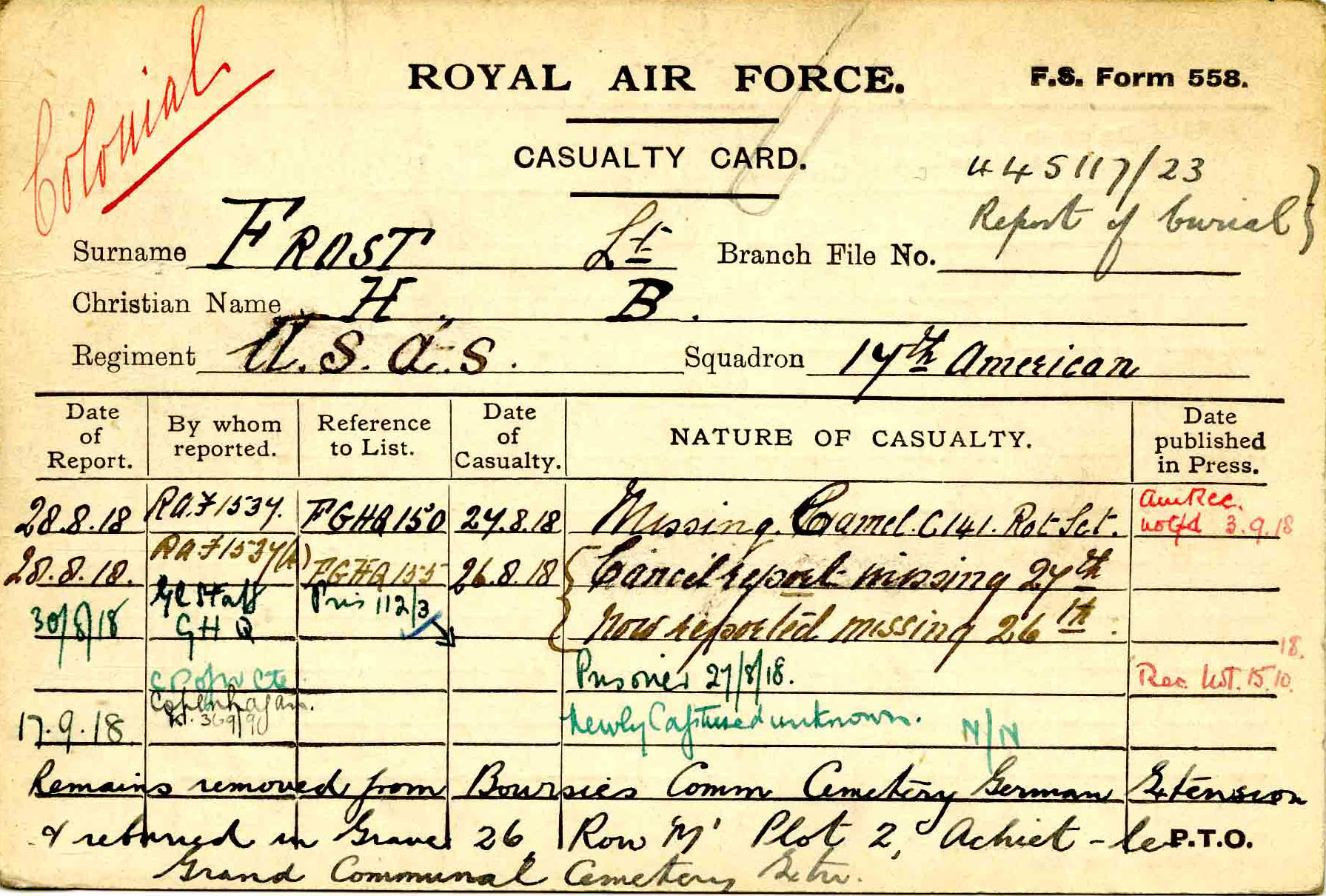

Tipton, taken prisoner, at some point sent a postcard with sketchy notes of the aftermath of the August 26, 1918, aerial battle, including the notation “Frost, severely wounded.”28 For a time it was thought that Frost was a prisoner of war, and he was reported as such.29 Eventually, however, his death was confirmed. According to his fellow pilot, Robert Miles Todd, who had been taken prisoner, Frost succumbed to injuries the evening of the 26th.30 Todd’s account is corroborated by information that Frederick W. Zinn, who devoted much effort to locating missing airman, was able to discover in an official German record. In a memo dated April 19, 1919, Zinn passed on a translation of the record to Frost’s sister Josephine Clifford Frost. “Lt. Engl. Aviator (American) died August 26, ’18 at the main dressing-station in Boursiers [sic; sc. Boursies], fracture of left & right lower thigh, hemorrhage left side, wound on the left cheek & left eye and hurt internally. Buried at Boursiers [sic]in the Military cemetery (on the road Cambrai-Bapaume) single grave No. 158.”31

An R.A.F. casualty card for Frost has a note (undated) indicating that Frost’s remains were removed from the Boursies Communal Cemetery, German Extension, and reburied in the Achiet-le-Grand Communal Cemetery Extension (Achiet-le-Grand is about eleven miles due south of Arras).32

In 1920 Josephine Frost travelled to Europe to visit her brother’s grave.33 In 1921, his body was brought home and he was reburied in the family plot in Mt. Pleasant Cemetery in Arlington, Massachusetts.34 He was an only son; neither of his sisters married, so he was the last of his line.35

mrsmcq July 13, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For his place and date of birth, see U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Henry Bradley Frost. The photo is a detail from a photo taken by Parr Hooper at Grantham in November 1917. The full photo appears after Chapter 3 of Hooper, Somewhere in France.

2 Information about Frost’s ancestry comes from records available at Ancestry.com; on the Bradleys, see Bradley, Descendants of Isaac Bradley.

3 See Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Frank C Frost.

4 On Frost’s education, see “College News,” pp. 238–9. On his travel, see Ancestry.com, UK, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960, record for Henry B Frost, and Ancestry.com, Book Indexes to Boston Passenger Lists, 1899-1940, record for Mr Henry Bradley Frost. For his thesis, see [Civil engineering theses, 1915].

5 See p. 81 of the “Necrology” in Annual for 1919 of the Thayer School.

6 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].” I do not find him in the squadron photo kept by Payden, and he is not among those who signed the back.

7 See commentary to Hooper’s letter of November 4, 1917, in Hooper, Somewhere in France.

8 Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917; Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 14, 1917.

8a Milnor, diary entries for November 22 through December 11, 1918.

9 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for H. B. Frost.

10 The other men Campbell mentions are Andrew (“Andy”) Carl Ortmayer, an American lieutenant who was serving as an instructor, and Reed Gresham Landis of the first Oxford detachment. A photo that presumably originally belonged to Campbell and is reproduced on p. 75 of Reed and Roland’s Camel Drivers, perhaps commemorates this period: it includes Campbell, Frost, and Landis, as well as “Andy from Chicago,” who is presumably Ortmayer.

11 Cablegrams 602-S and 821-R.

12 The cable (813-R) confirming the appointments of Leach, Middleditch, Pudrith, and Stahl is dated February 20, 1918, but they (and Stier & Sweeney) may not have received word and been sworn in until after Frost and Campbell. Or Campbell may not have been aware of their status, as they were apparently training elsewhere.

13 Dates are taken from Leslie C. Bradley’s post at “[WW1] WW1 Aviation Question by ‘Leslie C & Maria C Bradley’”; Bradley presumably had original documents related to Frost’s military service. (The information is now corroborated by Frost’s casualty form: see “Lieut. Henry Bradley Frost USAS”.) Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 16, indicates Frost had been with No. 209, but this is probably a slip of the pen. Bradley has indicated (private communication) that Frost was with 210, and this is corroborated by Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon and the 17thAero Squ.,” p. 158. On the (confusing and changing) location of No. 2 A.S.D. (Aeroplane Supply Depot), see mickdavis’s August 29, 2006, contribution to “Lieutenant Allen Denison” and Dye, The Bridge to Airpower, p. 179.

14 “210 Squadron.”

15 Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 435.

16 Information on the accident is taken from the relevant entry in the “Accidents Addendum” in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, and from a medical card for Lt. H. B. Frost, a copy of which Leslie C. Bradley obtained from the Royal Air Force Museum in London; I am grateful to Bradley for a scan of his copy.

17 Campbell’s diary entry for June 20, 1918, indicates that he found Frost already there when he (Campbell) arrived that day; Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 155, has Frost, Campbell, and others assigned to the 17th the next day. Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 188 and 193 (3 and 8), lists them as assigned on June 20, 1918.

18 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 29.

19 See Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 24; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 35 and 40.

20 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 40; on the 17th’s early activities generally, see pp. 35–40.

21 Regarding Frost’s leave, see Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 45 and 66 (where he is listed as on leave on August 20, 1918). The biography of Frost in Ticknor, New England Aviators 1914–1918 (vol. 1, p. 270) gives August 3, 1918, as the start date for his “two weeks’ furlough.”

22 See Murton Campbell’s diary entry for August 17, 1918, for the date of the move, which is unclear from other sources (Clapp A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 37; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 64).

23 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, reproduces the bombing report on p. 103; see Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 77, regarding Frost’s second patrol of that day.

24 See Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 77 and 79.

25 Clements, diary entry for August 26, 1918. See Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 80, on the German squadrons moved towards this part of the front.

26 Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II. “Sh57C.E” is a map reference that puts the combat in the general vicinity of Moeuvres, about nine miles east northeast of Bapaume. On understanding such map references, see Fetubi’s post of December 22, 2015, at “Boswell A.T.W and Gundill R.P. crashed and missing.” Franks, Bailey, and Duiven, The Jasta War Chronology, p. 233, indicate that H. Frommherz was responsible for shooting down Frost.

27 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 158.

28 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 75.

29 See “Prisoner in Germany.”

30 See Reed & Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 82; they cite a letter dated November 26, 1918, that Todd wrote to his mother, Lilles H. Todd.

31 Zinn, Memo, p. 1. Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 203, is almost certainly incorrect when he states that Frost “came down inside British lines.”

32 See “Frost, H.B.”

33 Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Josephine Clifford Frost.

34 “War Hero’s Funeral.”

35 This information is based on records available at Ancestry.com.