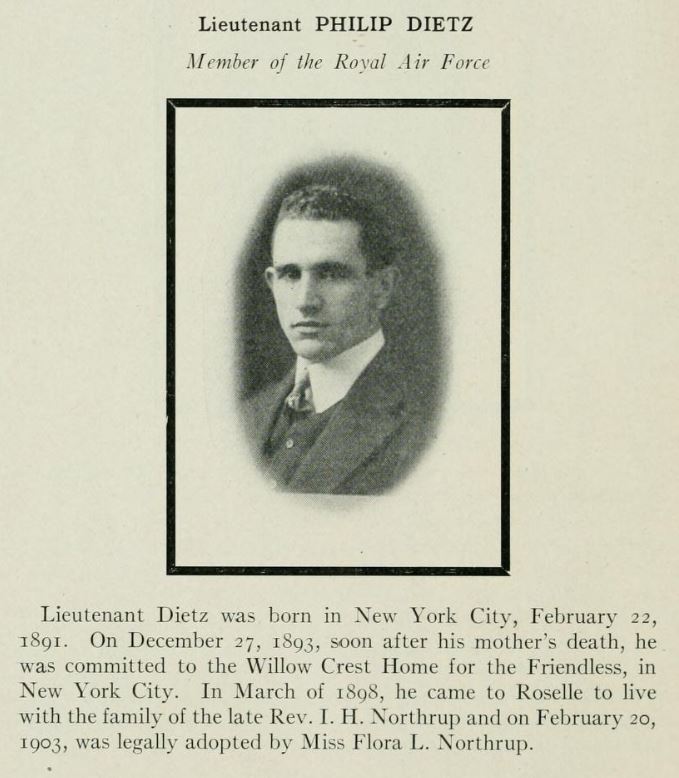

(New York City, February 22, 1891 – Alsace, July 30, 1918).1

Dietz’s father apparently deserted his wife and children; Dietz’s mother, having fallen ill, gave him and his sister Sarah up as orphans in late 1893. Sarah Dietz was one of the “orphan train children” sent out to Iowa in 1902. Philip was taken in by an elderly Presbyterian minister, Israel Hoit Northrup, in New Jersey. When Northrup died in 1902, his daughter Flora became Philip’s foster mother. Philip and his sister Sarah did not see one another again, but corresponded, and letters he wrote to her are preserved in the chapter about her in Orphan Train Riders: Their Own Stories.2

Dietz grew up and went to school in Roselle, New Jersey. He entered Sheffield Scientific School at Yale, working his way through college, at least initially, by waiting tables. He spent part of his time at Yale in the School of Forestry, and then graduated with the Sheffield class of 1915. Following graduation he worked for a time as a gardener and groundskeeper on a large estate, then taught at a military academy before becoming a director of athletics for a navy Y.M.C.A. in Brooklyn. He was working there in June 1917 when he registered for the draft and enlisted in the Signal Corps, Aviation Section.3

Dietz went through ground school at Ohio State University with the class that graduated August 25, 1917.4 He was one of the eighteen men from this group selected for training in Italy, and they were among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania, departing New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departing Halifax in a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. Dietz shared a room on board with William Ludwig Deetjen, Leonard Joseph Desson, and John Joseph Devery.5 The Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, and the men were informed, to their initial dismay, that they not going on to Italy, but were to remain in England, where they would repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University.

At the beginning of November, most of the men went from Oxford to Grantham to a machine gun school. Dietz, however, was one of twenty men who set off to Stamford, where they were to have flying instruction, instead. The War Birds entry for November 6, 1917, indicates that Dietz, Deetjen, and Roy Olin Garver were selected by Elliott White Springs, despite their lack of flying experience, to go to Stamford along with men with experience, because they had helped with clerical work for the detachment. Deetjen notes that the three of them went out together from Stamford one November morning to see Burghley House.6

Dietz’s R.A.F. service record does not list the training squadrons to which he was assigned, but Yale biographies of him indicate that he was at (in addition to Stamford) Andover, Salisbury, and Turnberry.7 Andover and Salisbury were both associated with bomber pilot training; Turnberry had a school of aerial gunnery. The service record notes that Dietz had experience as a surveyor (perhaps part of his Forestry School training) and had flown B.E.12s, the AW 160 (this perhaps refers to the Armstrong Whitworth FK.8 with a 160 horsepower engine), and DH.4s and DH.9s.8 By early March 1918 Dietz was far enough along in his training to be recommended for his commission; Pershing’s cablegram forwarding the recommendation is dated March 16, 1918. A cablegram to Pershing dated April 6, 1918, confirmed Dietz’s appointment as a first lieutenant.9

Towards the end of June 1918 Dietz was assigned to a day bombing squadron in General Trenchard’s recently constituted Independent Air Force; the I.A.F. was to undertake bombing of aerodromes, railroad transport, and industrial centers inside Germany.10 Charles Louis Heater described the challenge in reaching their squadrons faced by the seven second Oxford detachment members, including Dietz and himself, who were assigned to the I.A.F. at this time: “Nine months of training in England should have given the party of American pilots who left for the Independent Air Force on the last of June an idea of the sort of thing they were running into when they got to France, but most of them were unpleasantly surprised when they were bombed the first night in Boulogne, the second in Paris, the third while on their way to their squadrons in tenders, and several succeeding nights after reaching their stations.”11 Dietz, “while in Paris dropped in at the Yale headquarters for a visit with some old friends.”12

Heater goes on to say that Dietz was initially assigned to No. 104 Squadron R.A.F., then “was transferred to 99 Squadron, but the change did not make much difference since all three squadrons were on the same airdrome, Azelot, eight kilometers south of Nancy.”13 Both 104 and 99 were long-range bombing squadrons flying DH.9s. The commanding officer of 99, Lawrence Arthur Pattinson, notes that towards the end of June 1918: “The Squadron was now very much below strength in flying personnel available for raids. . . .” A few days later: “On [July 4] only seven pilots were available for a raid.”14 It was perhaps this shortage that prompted the transfer or loan of Dietz from 104 to 99; Pattinson reports that “Lieut. P. Dietz, of the U.S.A. Aviation Section, reported for duty as pilot on July 5th.”15

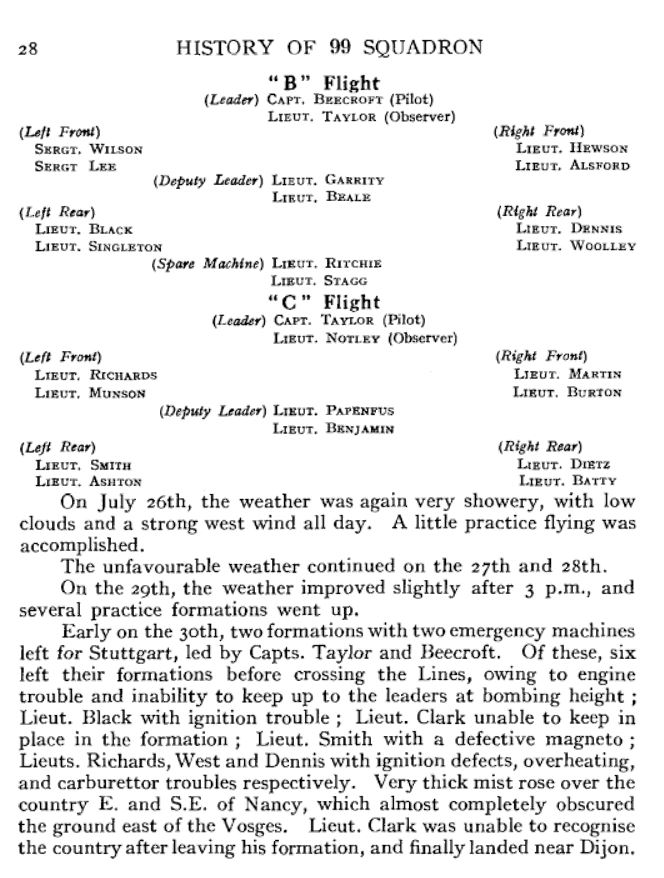

Dietz was assigned to C flight, and he and other newly assigned pilots were able to take advantage of days when the weather was not too inclement but operations were curtailed “owing to shortage of supplies, due to strikes in England” to get in “a considerable amount of valuable practice flying. . . .”16 Heater remarks that the “methods used by the British in training new pilots who had just come to the front were not altered for the Americans, except that instead of allowing three weeks to elapse between the day of arrival and the first trip over the lines, a two week interval was used for American personnel.”17 And, indeed, on July 20, 1918, C flight and Dietz were assigned to take part in a raid targeting the Mercedes aero engine works near Stuttgart.18 With equipment problems and unfavorable wind, Stuttgart was too far, and the railway station at Offenburg was bombed instead. Perhaps because of the strong wind, Dietz on take off struck a hangar; he and his observer/gunner Herbert Stanley Bynon immediately set off in another plane, but returned when Bynon became sick.19 (Bynon was admitted to hospital; he had already participated in at least four raids in June and, returned from hospital on August 20, 1918, went on to fly on about twelve more missions in the period from August through November 1918.20)

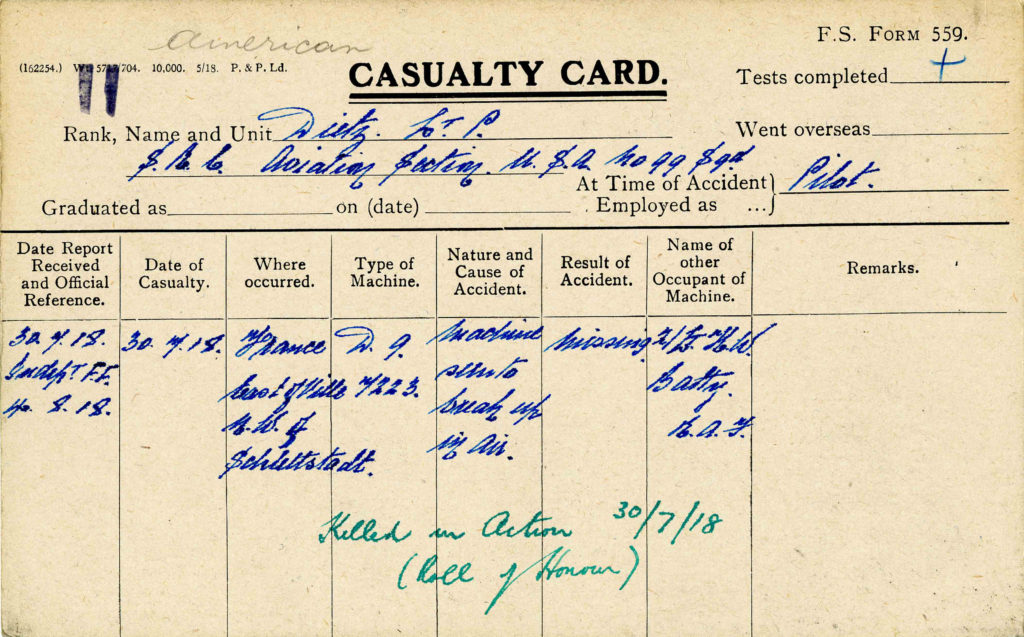

On July 22, 1918, another raid intended to target the Mercedes works was undertaken by No. 99 Squadron, but C flight and Dietz did not fly with them.21 Bad weather precluded anything but practice flights until July 30, 1918, when B and C flights left in the early morning for Stuttgart, with Dietz and his new observer/gunner, Horace Walter Batty (who had joined the squadron on July 11, 1918) flying DH.9 D7223 in the right rear position of C flight’s seven plane formation. Once again it was impossible to make the distance to Stuttgart, and bombs were instead dropped at Lahr near Strasbourg. As the considerably depleted formations (six of the initial fourteen planes from the two flights having returned early) crossed back over the Rhine, they were attacked by about twenty enemy aircraft.22 “Lieuts. Dietz and Batty were shot down and killed, their machine being seen to break up in the air”; according to the relevant casualty card, this occurred “east of Ville, N.W. of Schlettstadt.”23 Karl Kallmünzer of Jagdstaffel 78 is credited with having shot down a DH.9 near Rombach (about nine miles west northwest of Schlettstadt) at 8:40 a.m. Allied time (7:40 German time) on this day and is assumed to have been the German pilot responsible for downing Dietz’s plane.24

Heater, writing shortly after the war, remarked that “records show that more pilots went down on their first raid than went down on all other raids put together.”25 He also noted of the remaining men in the group of seven who had gone to the I.A.F. with Dietz, that their “enthusiasm underwent a change, when Lieutenant Dietz was killed on his first trip over the lines, and now our trips against the Hun had more of a personal touch than they had before.”26 They probably never knew that Dietz’s death was avenged, possibly by one of them, about two weeks later. Among the German casualties for which 55 and 104 were apparently responsible during their missions on August 12, 1918, was Kallmünzer, who died of injuries sustained when he crash landed after aerial combat that day over Wasselonne.26a

A note dated October 3, 1918, from the Frankfurt Red Cross reported Dietz and Batty to have been buried at Deutsch Rumbach. A similar report regarding Dietz made by Frederick Zinn and dated April 20, 1919, was forwarded to the U.S. Graves Registration Service.27 The source for both reports was presumably an entry in the Central Records Office in Berlin: “Dietz, Ph., Uffz. Flieger, 30.8. 18. tödl. abgeschossen [shot down and killed]. Beerdigt [buried] Deutsch-Rumbach.” The source for this information was the Inspektion der Fliegertruppen, the office that oversaw German military aviation.28

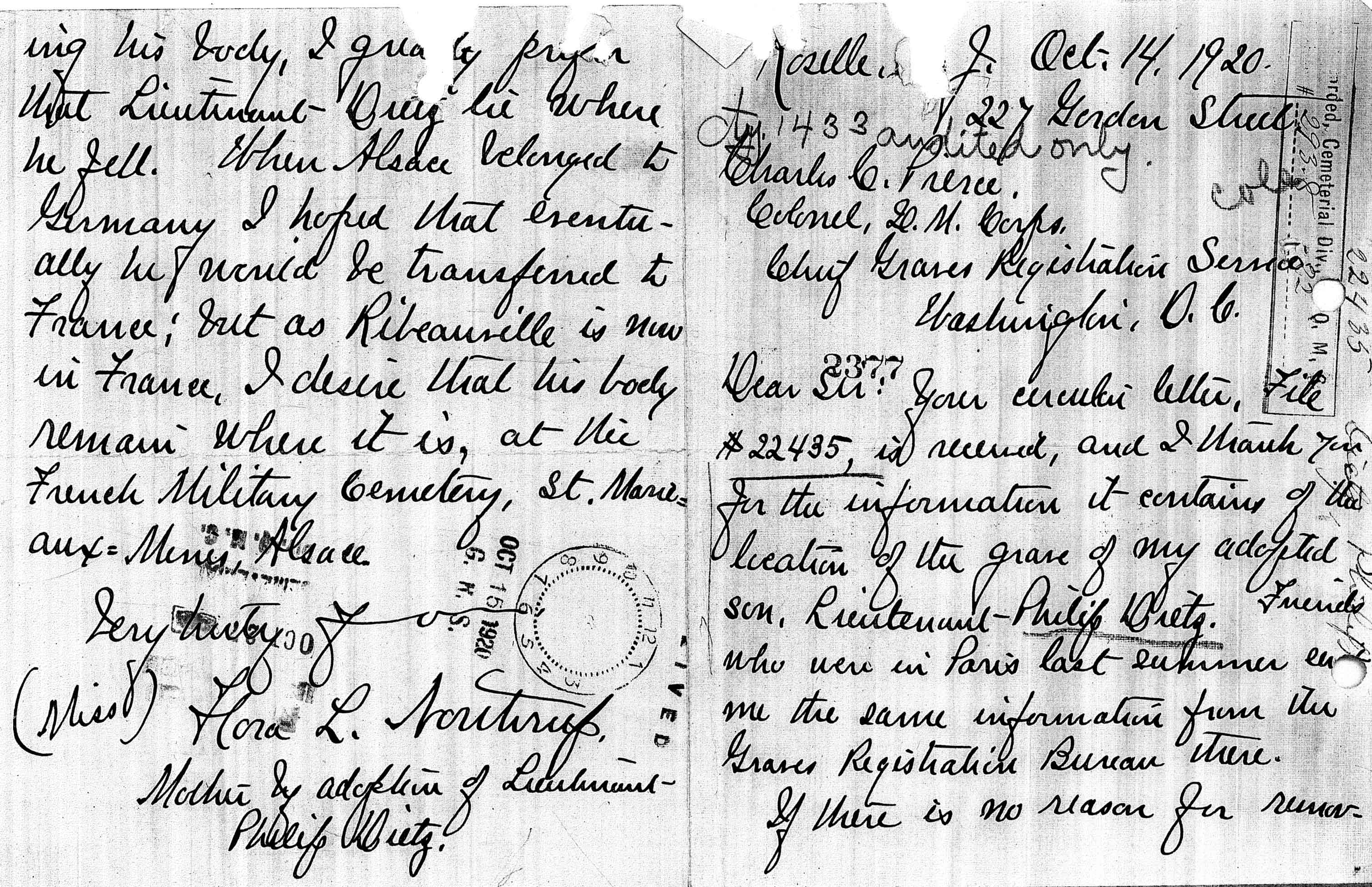

It was established more precisely that Dietz had been buried in the French Military Cemetery at Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, the commune to which Deutsch Rumbach (Rombach-le-Franc) belonged. His foster mother, Flora Northrup, was notified. The United States offered relatives the choice of leaving fallen soldiers’ remains in a European cemetery or having them returned to the U.S.; Northrup initially chose the former.

However, shortly after taking this decision she learned that Dietz—the only American in the Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines cemetery—was to be exhumed and reburied in a “concentration” cemetery in France in accordance with the policies of the Office of the Quartermaster General, and she requested that his body be shipped back and buried at Arlington. Delays occurred, arising apparently in part from Dietz’s status as an orphan and the need to establish that Northrup had the legal right to make decisions related to his (re)burial. His body was removed from Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines on August 24, 1921, and reburied in the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery on October 12, 1921. A little over a month later, on November 22, 1921, Dietz’s remains were taken from Meuse-Argonne preparatory to their being shipped to the U.S. on the St. Mihiel in December 1921. Further delay occurred when a Solomonic decision had to be made whether Dietz would be buried at Arlington or in Parkersburg, Iowa, where his sister lived. At last, on January 26, 1922, Dietz was given a permanent grave at Arlington.28a

In 1924, Batty, initially also buried at Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, was reburied in the Plaine French National Cemetery.29 In late 1923 one of Batty’s brothers emigrated from the family home at Stockton-on-Tees, County Durham, in the north of England, to Chicago; he was followed in early 1925 by his theater manager father and the rest of the family.30 Contact information for the family in Commonwealth Graves Commission documents includes a Chicago address, and for this reason Batty is sometimes assumed to have been an American.31

mrsmcq June 21 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Dietz’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Philip Dietz. The photo is a detail from a group photo of Squadron 7 at the Ohio State University School of Military Aeronautics.

2 “Sarah Dietz Tjebkes”; “Northrup, Rev. I. H.”; Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census and 1910 United States Federal Census, records for Phillip Deitz [sic].

3 See Dietz’s letter of January 3, 1910, in “Sarah Dietz Tjebkes,” (p. 105), regarding waiting tables; a letter from 1916 (pp. 105-06) describes his post-college activities. On his college career generally, see “Lieut. Dietz, Ex-’15, Missing in Action.”

4 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

5 Deetjen, diary entry for September 23, 1917.

6 Deetjen, diary entry for November 14, 1917.

7 “Lieut. Dietz, Ex-’15, Missing in Action,” and entry for Dietz on pp. 188-89 of volume 1 of Nettleton, Yale in the World War.

8 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for Philip Dietz.

9 Cablegrams 739-S and 1049-R.

10 “List of American Fliers who Served with the Independent Air Forces.” There is considerable controversy surrounding the I.A.F. and Trenchard. Chapter 11 of Wise’s Canadian Airmen and the First World War provides an account and an assessment based on original documents that is worth reading. See also his description of the shortcomings of the DH.9 on pp. 293–94, 303, and 309.

11 Heater, [Informal account], p. 124. The other American pilots in the group were Kenneth MacLean Cunningham, Linn Daicy Merrill, Phillips Merrill Payson, George Clark Sherman, and Horace Palmer Wells.

12 “Lieut. Dietz, Ex-’15, Missing in Action.”

13 Heater, [Informal account], p. 124. The “List of American Fliers who Served with the Independent Air Forces” indicates that Dietz served with 104 and 99. Dietz’s casualty form (“Lieut. Philip Dietz US Air Service att RAF”) indicates he was attached to 104 on July 2 and posted to 99 on July 6, 1918.

14 Pattinson, History of 99 Squadron, pp. 18 and 21.

15 Pattinson, History of 99 Squadron, p. 22.

16 Pattinson, History of 99 Squadron, p, 23.

17 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 117.

18 Pattinson, History of 99 Squadron, p. 26, indicates the raid took place on July 21, 1918; Rennles, Independent Force, p. 63, describes the raid under the date July 20, 1918, and Rennles’s dating is confirmed by entries for July 20, 1918 in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II.

19 Rennles, Independent Force, p. 63.

20 See Pattinson, History of 99 Squadron, pp. 27 & 34, for dates of Bynon’s admission to hospital and return to squadron; see Renless, Independent Force, passim, regarding his participation in raids.

21 Pattinson, History of 99 Squadron, p. 26; Rennles, Independent Force, p. 66.

22 See Pattinson, History of 99 Squadron, p. 23, for the date Batty joined the squadron; p. 27-29 on the makup of the formations and the raid.

23 See Pattinson, History of 99 Squadron, p. 29, and “Dietz, P.” Henshaw, in the entry for this casualty in The Sky Their Battlefield II, locates the break up of the plane east of Lille, but this is probably a misreading of the casualty card or a mistranscription in another document.

24 Rennles, Independent Force, p. 69; see also the entry for this date in Franks, Bailey, and Duiven, The Jasta War Chronology, as well as the one in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II; see the latter, pp. viii-ix, on time issues.

25 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 118.

26 Heater, [Informal account], p. 126.

26a See Rennles, Independent Force, p. 82, where he credits the downing of Kallmünzer to 55. However, given that he was apparently shot down over Wasselnheim (Wasselonne) not far from Hagenau, 104’s target, it seems to me more likely that 104 was responsible. Rennles notes Kallmünzer had been in “combat with DH4s,” but it would have been understandable if 104’s D.H.9s had been mistaken for D.H.4s in German reports.

27 These documents are in Dietz, World War One Burial File.

28 Nettleton, Yale in the World War, vol. 1, p. 188, reproduces the German Central Records Office entry.

28a Information in this paragraph is taken from documents in Dietz, World War One Burial File.

29 “Second Lieutenant Horace Walter Batty.”

30 Ancestry.com, Massachusetts, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1963, records for Edvard [sic] John Batty and for Walter Batty.

31 “Second Lieutenant Horace Walter Batty.”