(Newport News, Virginia, July 12, 1891 – Maulan, France, October 3, 1918)1

Oxford & Grantham ✯ Harrietsham ✯ No. 5 T.D.S. ✯ Wyton ✯ Marske & Stonehenge ✯ France ✯ Epilogue

Perkins family members trace their ancestry to a Humphrey Perkins (or Purkins) who came to Virginia from England in the seventeenth century, and there is some speculation that they are descended from Francis Perkins (Perkin) of the colony at Jamestown.

Pryor Richardson Perkins’s grandfather, Carter Perkins, fought in the War of 1812, and Perkins’s father, also Carter Perkins, was old enough to have served in the Confederate Army. The younger Carter Perkins had trained and practiced as a dentist; after the Civil War he became involved in the lumber trade before settling in Newport News; there he practiced dentistry again for a time as well as becoming involved in various business enterprises. He married his first wife shortly before the Civil War; they had four sons and a daughter. A few years after his wife’s death in 1883, Perkins married Mary Sue Richardson, daughter of William Pryor Richardson, a graduate of the College of William and Mary who went on to study medicine in Baltimore before returning to eastern Virginia to practice medicine. Pryor Richardson Perkins—who went by Richard or Dick—was the second of four children and only son of Carter Perkins’s second marriage.2

Perkins attended high school in Newport News and went on to the College of William and Mary. His college attendance can be documented for the year 1911; he appears not to have graduated.3 He was employed as a clerk between 1909 and 1917, initially in the Newport News office of the Clyde Steamship Company, which operated transportation steamships along the east coast, and then for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway.4

Meanwhile, in the latter part of 1915, when a field artillery unit of men from Hampton, Newport News, and other nearby Virginia towns was organized, Perkins, along with Edward Carter Braxton Landon, was among the first to enlist in what soon became “Battery D.”5 Their military activities initially involved drilling one evening a week. In June 1916 Battery D learned that it should “be prepared to move on arrival of Orders” because of the continuing tense situation on the U.S.–Mexico border.6 After some time camped at Richmond, Virginia, Battery D left for Texas, where they were stationed in the vicinity of San Antonio from October 1916 through the following March.7 When the U.S. entered the war in Europe shortly after the return of the unit to Virginia, the men of Battery D were assigned to protect shipping installations at Newport News. Perkins, however, again with Landon, transferred to aviation. They were enrolled in the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University and their No. 8 Squadron graduated from ground school there on September 1, 1917.8

Along with many of the men from the ground school classes of August 25 and September 1, 1917, Perkins chose or was chosen to train in Italy. It had initially been assumed the men would go to France for their actual flying training, but most were delighted when the possibility of “sunny Italy” was raised. On September 6, 1917, according to Perkins’s ground school classmate Murton Llewellyn Campbell, “Orders arrived this morning before Squad was out of bed. Believe me, it did not take long for the gang to get out. Everybody was ready at 9 o’clock to leave. There was a trifle of restlessness mixed in with the bunch on account of waiting so long for orders. . . . Twenty-three of No. [8] Squadron were ordered to N.Y. I expect we will all go to Italy. . . . This is a lively bunch, especially Perkins. It was well for us to get a private car, because we needed it.”8a They arrived the next day at Mineola on Long Island, where they were based for the next week and a half. On September 18, 1917, (again according to Murton Campbell) “We piled out at 4 A.M., had breakfast early and ‘fell in’ at 6 in front of Gate No. 6 with full equipment. We marched over to Garden City and took the Penna. to Long Island City, where we embarked on the Gen. Meigs, which took us down East River and up the Hudson to a dock. Then we walked aboard the Cunard liner, Carmania. . . . ”8b After an initial stop at Halifax, the Carmania set out as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. The 150 men of the detachment travelled first class and had plenty of leisure, apart from daily Italian lessons conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them, and submarine watch duty towards the end of the voyage.

Oxford and Grantham

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. Various explanations have been offered for the snafu, to use an acronym from the next war.9 Whatever the reason, the detachment made their peace with the change and in retrospect recognized the benefit of the R.F.C. training they received in England over the next few months. In the short term, classes at Oxford covered much of the same material that the men had had at ground school in the States, so that the cadets were not overburdened with homework or studying and had time to enjoy the amenities of Oxford college life and to explore the surrounding countryside.

After a month, on November 3, 1917, most of the detachment, including Perkins, left Oxford for Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend gunnery school at Harrowby Camp. Fifty of these men departed on November 19, 1917, for flying schools, but Perkins, as well as Landon, remained at Grantham until early December and completed the second of two machine gun courses, one on the Vickers and one on the Lewis machine gun. When not in classes, the men explored the countryside. Perkins, by the evidence of a postcard he sent from Grantham to one of his nieces, Mary Graham Lett, was also able to make a visit to London.10

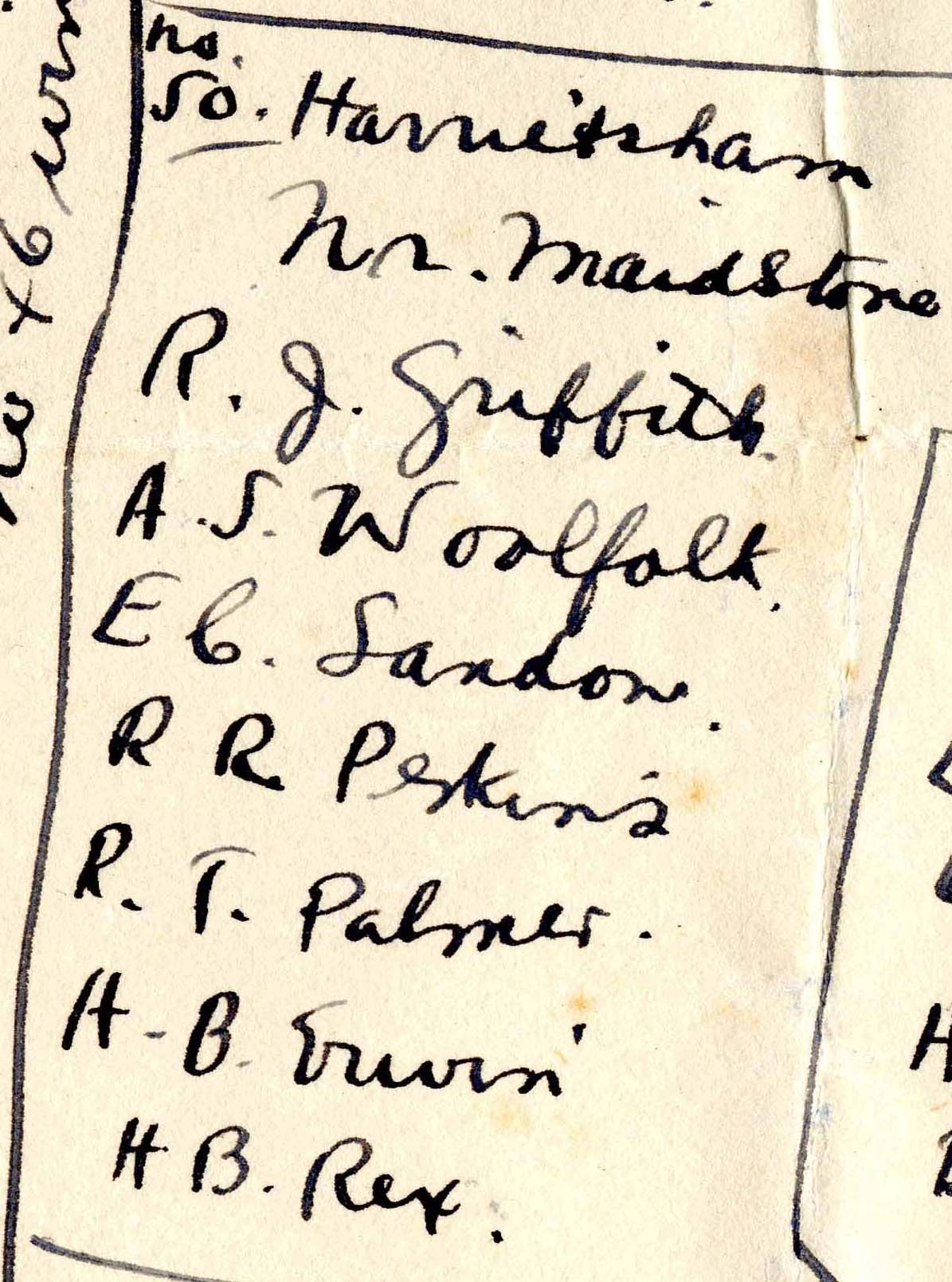

Harrietsham (50 H.D. Squadron)

On December 3, 1917, the remaining men at Grantham were posted to squadrons. Perkins, along with Robert Jenkins Griffith, Harrison Barbour Irwin, Landon, Robert Thomas Palmer, Hilary Baker Rex, and Albert Sidney Woolfolk (all of whom, with the exception of Rex, had been in Perkins’s O.S.U. ground school class), was assigned to No. 50 Squadron in Kent; No. 50 was a home defense rather than a training squadron.11 Its aircraft at the turn of the year included the B.E.2 and the A.W. FK.8, both two-seaters used for reconnaissance and bombing, and the B.E.12b, a single-seater night fighter.12 The squadron’s headquarters was at Harrietsham, near Maidstone, but its flights were at this time detached to Bekesbourne and Detling. Griffith, Irwin, and Woolfolk went to C flight at Bekesbourne near Canterbury, while Perkins, along with Landon, Palmer, and Rex, was assigned to B flight at Detling.12a

Palmer’s pilot’s flying log book and one of his letters home provide some information about the men’s time at Detling.13 The weather was, of course, not often good for flying at this time of year. Nevertheless, Palmer was able to put in a little time as a passenger in both a B.E.2e and an A.W., and Perkins was perhaps able to do the same—although there is no record of flights from this period in his log book. Palmer’s log book indicates that these were joy rides rather than instructional flights.

No. 5 T.D.S.

Towards the end of January 1918, after nearly two months at No. 50 Squadron, Perkins, along with Landon, Palmer and Rex, was posted to No. 5 Training Depot Station at Easton on the Hill, about two miles south-southwest of Stamford.14 Here they would have encountered other second Oxford detachment members, some at nearby No. 1 T.D.S., and some at No. 5 T.D.S. Among the latter was John Warren Leach who, like them, had been at a home defense squadron until the end of January. Unlike them, Leach had already received a good deal of instruction, thus underlining the discrepancies in training progress among the men of the detachment.

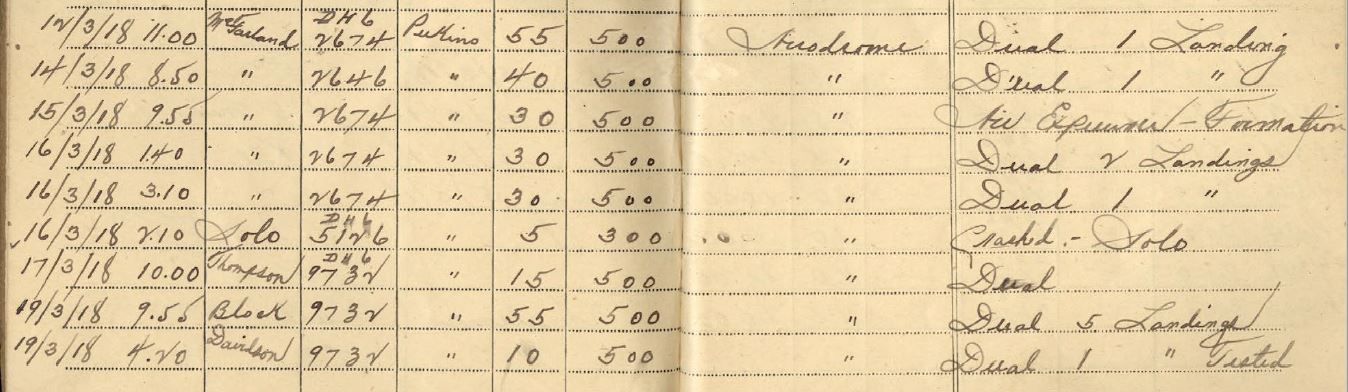

Perkins’s first entry in his log book records a flight of twenty minutes on February 4, 1918, when he was a passenger in B.E.2d 4494 piloted by Foster Murray MacFarland.15 Perkins made two similar dual control flights with MacFarland over the next two days. He did not fly again, perhaps because of bad weather, until February 18, 1918, when he went up again with MacFarland, this time in a DH.6, a dual-control training plane.

February 18, 1918, was the day that Clark Brockway Nichol, a second Oxford detachment member who had been posted to No. 5 T.D.S. at the same time as Perkins, went up solo, crashed, and was killed. Three days later, a funeral was held for him, and Perkins, along with John Joseph Devery, Landon, Rex, Wilbur Carleton Suiter, and Woolfolk, served as pall bearers.15a

Perkins continued to put in hours flying DH.6s dual, and once as a passenger in an R.E.8, fairly steadily until March 16, 1918. On that day, after two dual flights and some practice landings, Perkins took DH.6 C5126 up solo for the first time and crashed five minutes into the flight.

He was evidently not hurt, as he went up again dual the next day with Thomas Frederick Wailes Thompson. I find no record of what happened to C5126, but, as it does not appear again in Perkins’s log book, or in Palmer’s, it seems likely it badly damaged. This, Perkins’s only crash during his training, was notable enough that Landon apparently wrote home about it—which Perkins was careful not to do, and Perkins’s exasperation is evident when he later found that word of the crash had gotten back to his mother.16

Perkins worked on his landings, and on March 21, 1918, after going up twice with MacFarland in DH.6 [A]9732, he took the same plane up solo and made two uneventful landings.17 He now began piling on the hours of solo flying. On April 5, 1918, he flew to Wyton and back, thus passing one of the tests, a cross country flight, required for graduation from the first stage of R.A.F. training. A week later he began flying B.E.2d 4494 dual, and on April 24, 1918, he flew it solo for the first time. He fulfilled another graduation requirement, the altitude test, on May 8, 1918, when he flew a B.E.2e for an extended period of time at 8,000 feet. From there, in early May, he moved on to instruction on R.E.8s. When he flew an R.E.8 solo on May 10, 1918, he passed the final test for graduation. He made more solo flights over the next two days, and by the end of the day May 12, 1918, could record just over twenty-two hours of solo flying, in addition to nearly fifteen hours dual.

The recommendation for Perkins’s commission had been forwarded to Washington a little more than a month previously. Pershing had evidently been made aware that many American cadets who had been promised flight training in Europe had, because of insufficient instructional facilities, been progressing at uneven and at times very slow rates. In a cable dated March 13, 1918, Pershing wrote to the War Department that these men “would have been commissioned prior to this date if training facilities could have been provided. These conditions have produced profound discouragement among cadets.”18 To remedy this injustice, and to put the European cadets on an equal footing with their counterparts in the U.S., Pershing asked permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .” Washington approved Pershing’s plan in a cable dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.”19 Perkins’s name was among those in Pershing’s cable of April 8, 1918, recommending that the men be commissioned “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying.”20 Washington took its time responding to this cablegram, and it wasn’t until May 13, 1918, that the confirming cable was sent.21 For Perkins and most of the other second Oxford detachment members listed in the April 8, 1918, cablegram, the “non-flying” status was irrelevant, as they done enough training and flying to qualify for their commissions by the time word of the May 13, 1918, cablegram from Washington trickled down.

Wyton (No. 5 T.S.)

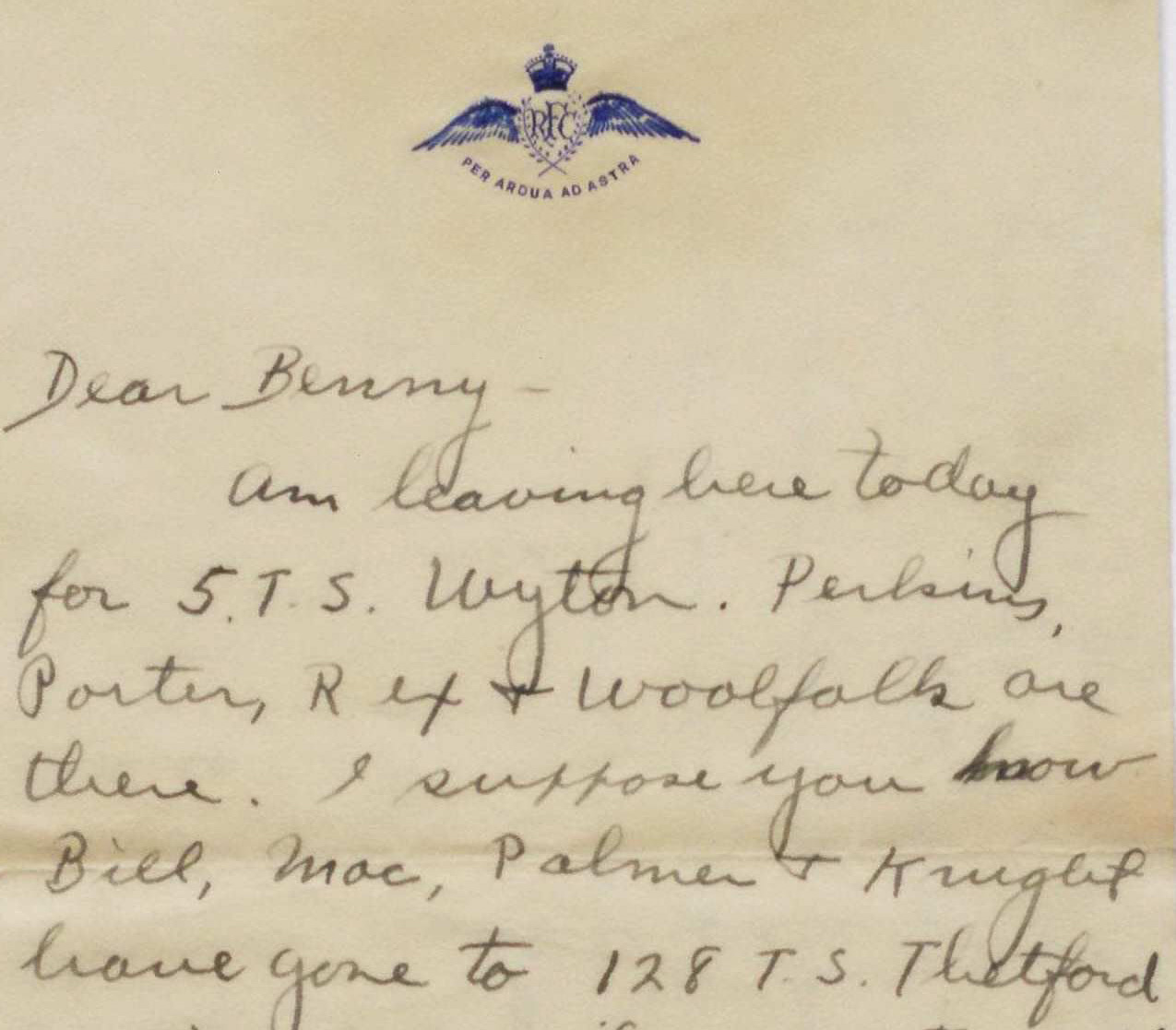

In a letter of May 22, 1918, to his niece, Lalie Lett, Perkins indicates that news of the commission had still not reached him. However, “[I] Have received my graduation certificate from this Squadron and am now entitled to wear my wings.” There are no entries in Perkins’s log book from May 13 through May 19, 1918, and it is likely that this represents his taking the leave that was routinely given flying students on graduation.

Perkins made his final flights at No. 5 T.D.S. on May 20 and 21, 1918, before beginning his next stage of training at No. 5 Training Squadron, at Wyton—with which he was already familiar from his cross country flight test. Rex and Woolfolk were also there, as were Robert Brewster Porter from Perkins and Woolfolk’s O.S.U. ground school class and Charles Carvel Fleet from the class ahead of them.22 Neither Landon nor Palmer went with Perkins to Wyton.

Perkins made his first flight at No. 5 T.S. on May 25, 1918 as a passenger in a DH.9 piloted by William Petre; it was apparent now that he was to be trained as a bombing or observation plane pilot. Over the next three weeks, he put in many hours in DH.6s, B.E.2e’s and DH.9s, including some solo flying on the first two types. Finally, on June 18, 1918, he took a DH.9, [D]5562, up solo for a twenty-five minute flight. His log book indicates that he did not fly again in June, but in early July he was once again flying solo, usually in a DH.9, and he began practicing formation flying, aerial flying, and evasive flying. By the end of July, his number of hours flying solo, nearly forty-eight, exceeded the number flown dual, for a total of just over eighty-one hours.

Marske and Stonehenge

On the last day of July 1918, Perkins went to No. 2 Fighting School at Marske-by-the-Sea in the northeast of Yorkshire for advanced flying training. His first two weeks there were presumably spent in classes on the ground; he does not record flying there until August 12, 1918. On that date he went up dual in an Avro, evidently giving his instructor the opportunity to check his flying skills. This was apparently standard practice, but slightly ironic, given that Perkins had never flown this basic training plane before. He must have passed muster; four days later he began piloting DH.9s with an unnamed observer as his passenger, and over the next few days, he went up numerous times and practiced formation flying, firing, and aerial fighting.

Perkins made his last flight at Marske on August 21, 1918, just before 3 p.m. He must then have caught a night train for the long journey south to Wiltshire, as his log book records his presence at Stonehenge, a little west of Amesbury, the next day. The No. 1 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping at Stonehenge was his final training assignment. He would probably have crossed paths there with first Oxford detachment members Fremont Cutler Foss and Gilbert Allan Woods, who were just finishing up. As at Marske, Perkins’s initial flight was a test flight with an instructor, this time, however, in a DH.9. The next day, August 26, 1918, he was piloting, but back in a B.E.2e. He continued to fly B.E.2e’s over the next days, usually with a passenger, observer-in-training Thomas Norman Drake. They practiced formation flying, bombing, and cloud flying. On the first of September 1918 formation flying took them over the Isle of Wight during a flight that lasted nearly three hours. Two days later, they made a cross country flight to Bath. On three occasions Perkins wrote in the log book’s remarks column “head in bag”—this does not, as I initially assumed, mean that the ride was nausea-inducingly bumpy for one or both of the them. Rather it refers to a way pilots could practice flying through clouds when there were none. According to Perkins’s fellow second Oxford detachment member Vincent Paul Oatis, who had been at Stonehenge in June, “When there were no clouds they used a business like an awning of black cloth that completely enclosed the pilot. You can’t see a thing but your instrument board.”22a On September 5, 1918, Perkins flew dual in a DH.9A, i.e., a DH.9 with the more powerful American “liberty” engine, but was back piloting a B.E.2e for three flights on September 6, and again on September 7, 1918. He then, on September 8 and 13, 1918, piloted a DH.9 on seven flights before moving on to a second dual flight in a DH.9A on the fifteenth. Over the course of the week, he flew as the pilot of DH.9A’s nine times. He practiced cloud flying and made an extended formation practice flight to Cardiff. On his final four flights he was unfortunate to be flying DH.9A [E]8409, which had a “dud engine.” This meant that his flights were short, and his last, a test, was only ten minutes. At the end of his last day of training, September 20, 1918, Perkins recorded that he had accumulated seventy-five hours and fifteen minutes of solo flying, sixteen of them in DH.9s and four in DH.9A’s.

France

On September 27, 1918, Perkins, along with Foss, Woods, Woolfolk and others, was ordered to France, to Colombey-les-Belles, the American aircraft depot south of Toul.23 It would have taken three or four days to cross the Channel and then to travel from the coast to the American sector, so they probably did not arrive at Colombey-les-Belles until the last day of September or the first of October. On October 2, 1918, Perkins and Woolfolk were assigned to the 20th Aero Squadron.24 Other than Melville Folsom Webber, who was assigned to the 20th Aero in November 1918, Perkins and Woolfolk were the only members of the second Oxford detachment to serve with the 20th Aero. However, a number of men from the detachment were stationed at the nearby 11th Aero Squadron.

The 20th Aero Squadron, along with the 11th and the 96th , had been assigned to the newly constituted American 1st Day Bombardment Group at Amanty a few miles west of Colombey-les-Belles, on September 10, 1918, two days before the opening day of the St. Mihiel Offensive. The 96th flew Breguet 14B.2s, while the 11th and 20th had American DH-4s. After St. Mihiel, in preparation for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the three squadrons were relocated to Maulan, about twenty miles north-northwest of Amanty. On the opening day of the offensive, September 26, 1918, the 20th Aero lost a number of crews during their first mission, a raid on Dun-sur-Meuse, and it was apparently in response to this shortage of flying officers that Perkins and Woolfolk were assigned to the 20th on October 2, 1918.25

The next day, October 3, 1918, men of the 20th Aero flew no missions but, along with crews from the other two squadrons, made practice formation flights.26 Perkins went up in a DH-4—a plane of the type that was the predecessor of the DH.9s and DH.9A’s he had trained on—with Leonard Beeman Fuller as his observer; Fuller had also reported to the 20th Aero the preceding day.27 The DH-4 crashed, and both men were killed.

Clarence George Barth, an enlisted man who served with the squadron, wrote in his History of the Twentieth Aero published in 1920 that “Something went wrong with the engine and they crashed, killing both instantly.”28 It is not apparent whether this is based on Barth’s personal knowledge or taken from one of his sources. Whereas it is possible to find individual records for most R.A.F. plane casualties, this is not the case for those associated with the American Air Service—either because such records were not made or kept, or because they are not public. Thus it is not known which plane Perkins and Fuller were flying, nor is there official information regarding what went wrong.

The crash may have occurred at the airfield itself, as one of the operations orders for the 1st Day Bombardment Group on October 3, 1918, allocates three hours for “the removal of crashed planes, or debris of any kind from the flying fields.”29

Epilogue

Word of Perkins’s death reached his parents at the end of October 1918 in a communication from Woolfolk; Woolfolk provided no details.30 Fuller’s sister, apparently through official channels, learned of Fuller’s death on November 4, 1918, and his name appeared on the official casualty list on November 11, 1918.31 Perkins’s name for some reason does not appear until the list of December 1, 1918.32 Both men were buried in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery near Romagne-sous-Montfaucon.

Fuller was from Vermont, the son of a farmer and Methodist pastor, Asa Colby Fuller. A junior at Wesleyan College in Connecticut when the U.S. entered the war, Fuller initially enlisted in the marines but then transferred to the aviation service and trained at M.I.T., Cornell, and in Texas.33 He was a second lieutenant in the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps when he sailed with a casual detachment from Hoboken for Europe on August 18, 1918.34 I have no record of his activities from then until he was assigned to the 20th Aero on October 2, 1918.

After the war Fuller’s mother, Harriet (Hattie) A. Fuller, née Borroughs, expressed interest in the Gold Star Mothers Program which facilitated pilgrimages to European war graves.35 Ship manifests do not include enough detail to be certain that she actually made the journey.

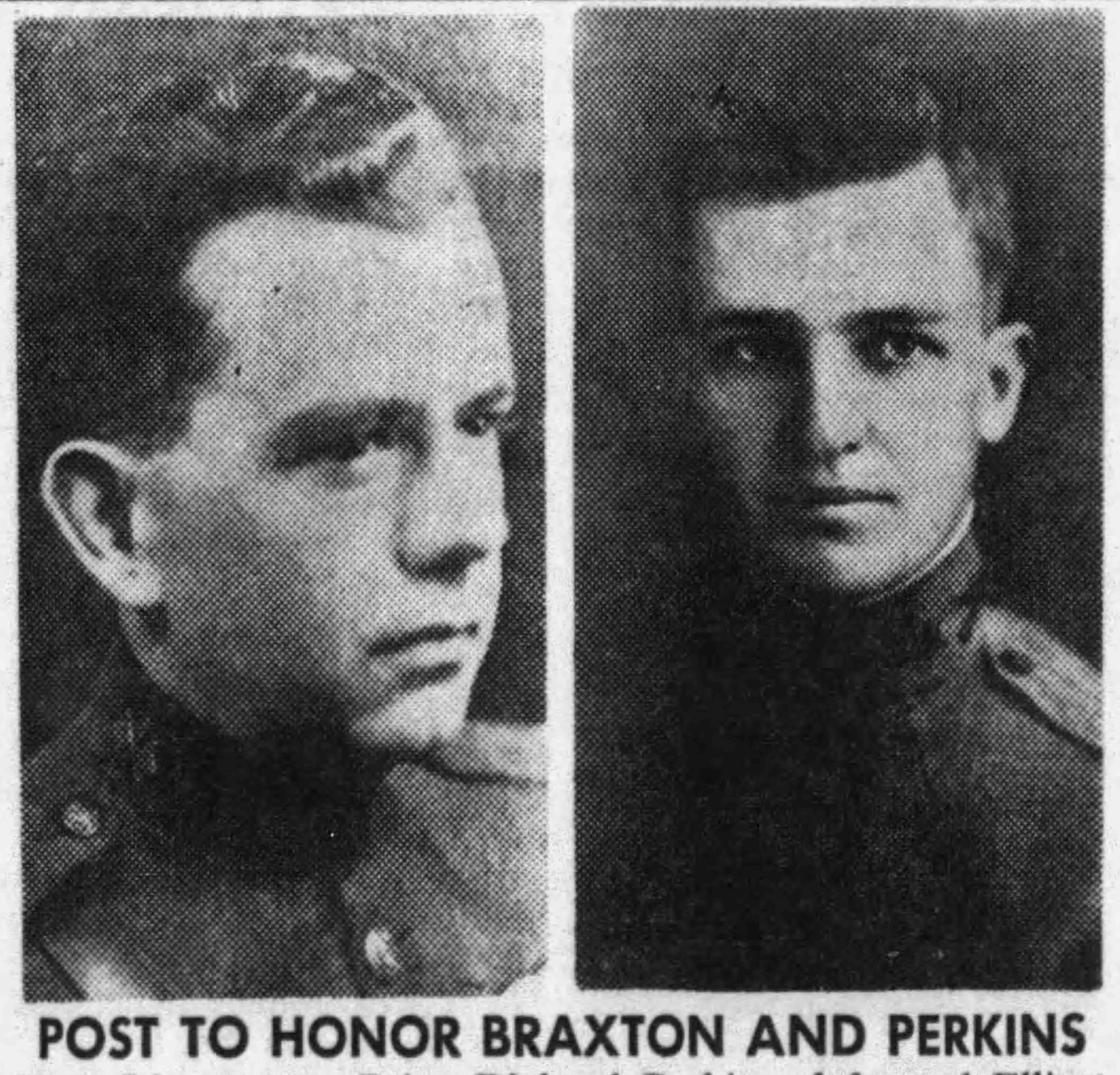

Perkins’s mother travelled as a Gold Star Mother to France in the summer of 1931.36 She was active in the auxiliary of the Newport News American Legion Post that had been founded in 1919 and named for her son and for another man from Newport News who had been killed during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, Elliott Muse Braxton III, a second cousin Perkins’s friend and fellow second Oxford detachment member, Edward Carter Braxton Landon.

Perkins’s log book passed to his older (full) sister, Anne, and she gave it along with other memorabilia to what is now the Virginia War Museum in Newport News.37

mrsmcq March 18,2022; M. L. Campbell diary entries added to opening section Jun 12, 2023

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Perkins’s dates of birth and death are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., Veterans Administration Master Index, 1917-1940, record for Pryor R Perkins; his place of birth is a reasonable surmise. His middle name is sometimes given as “Richard.” I find no official documentation of his full name, but have assumed that the name—Pryor Richardson Perkins—provided in Bruce’s Virginia: Rebirth of the Old Dominion, vol. 3, p. 204, is correct. The photo is a detail from a group photo of Perkins’s ground school class at O.S.U.

2 On Perkins’s family, see documents available at Ancestry.com, and the entry for Carter Perkins on pp. 203–05 of volume 3 of Bruce, Virginia: Rebirth of the Old Dominion.

3 Perkins’s name and picture appear in The Colonial Echo (the William and Mary yearbook) for 1911, but not in subsequent years until 1919, when his name is on the list of alumni killed in the war. There is some evidence that he entered with the class of 1914 which, however, had an enormous attrition rate. For “Perkins ’14,” see Griffing, Sixth Catalogue of [Theta Delta Chi], p. 74; on attrition, see The Colonial Echo for 1914, p. 32; and Thelin, The Attrition Tradition in American Higher Education, pp. 9– 10

4 Information on Perkins’s employment is gleaned from Newport News directories available at Ancestry.com; see also “Pryor Richard [sic] Perkins.”

5 Sayre and Roberts, A Brief History of Battery “D”, p. 25.

6 Ibid., p. 4.

7 Ibid., passim.

8 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

8a Murton Campbell, diary entry for September 6, 1917.

8b Murton Campbell, diary entry for September 18, 1917.

9 See, for example, the explanations supplied by Hamilton Hadley on p. 4 (286) of “Foreign Aviation Detachments,” by Geoffrey Dwyer on p. 2 of “Report on Air Service Flying Training Department in England,” and by Claude E. Duncan as recorded in Sloan and Hocutt, “The Real Italian Detachment,” p. 44.

10 Perkins, Postcard.

11 See Foss’s list of “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers.

12 On the planes used at 50, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 408.

12a Rex, World War I Diary, entry for December 5, 1917.

13 Palmer, Pilot’s Flying Log Book; Palmer, Letter dated December 12, 1918.

14 Palmer’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card indicates he left No. 50 Squadron for No. 5 T.D.S. on January 28, 1918, and Perkins was probably transferred at the same time. Perkins’s letter of May 5, 1918, indicates that he and Landon had thus far been training together. And see Rex, World War I Diary, entry for January 30, 1918.

15 Unless otherwise noted, details of Perkins’s flying training is taken from his Pilot’s Flying Log Book. I have identified some men he flew with for whom he provided only last names by looking at the relevant Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919 (Series AIR/76) digitized at The National Archives (U.K.) web site.

15a Rex, World War I Diary, entries for February 18 and 21, 1918.

16 Perkins, Letter of May 22, 1918.

17 Like many pilots, Perkins tended to leave the letter prefix off the serial numbers of the planes he flew; they can usually be supplied by consulting Robertson, British Military Aircraft Serials 1878–1987.

18 Cablegram 726-S.

19 Cablegram 955-R.

20 Cablegram 874-S.

21 Cablegram 1303-R..

22 Fleet, Letter to Benson dated May 31 [1918], in Benson, Leslie A. A. Benson Collection, 1917-1919.

22a Oatis, letter of July 12, 1918. See also Barber, Stonehenge Aerodrome and the Stonehenge Landscape, p. 19, on the “head in bag” test.

23 Biddle, “Special Orders No. 187.”

24 “Roll of Officers of the 20th Aero Squadron.”

25 Barth, History of the Twentieth Aero Squadron,” p. 39.

26 “First Day Bombardment Group,” p. 111.

27 “Roll of Officers of the 20th Aero Squadron.”

28 Barth, History of the Twentieth Aero Squadron, p. 39.

29 “First Day Bombardment Group,” p. 38.

30 “Lieut. Perkins Dead in France.”

31 “Casualties”; “List of Casualties Reported Among the United States Forces Overseas,”dated November 11, 1918, p. 26.

32 “List of Casualties Reported Among the United States Forces Overseas,” dated December 1, 1918, p. 24.

33 “Miss Fuller has Lost Chum-Brother.” On Fuller’s family, see records available at Ancestry.com.

34 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, [Outgoing], record for Leonard B Fuller.

35 Sewell and Palin, eds., U.S. World War I Mothers’ Pilgrimage, 1929, record for Mrs Harriet E Fuller.

36 “Society,” Daily Press.

37 “Museum Gets Scruggs Collection.”