(Newark, New Jersey, August 23, 1896 – Castle Bromwich Aerodrome, Warwickshire, England, February 28, 1918).1

Ludwig’s paternal grandparents came from Germany. According to one account, his grandfather participated in the German Revolution of 1848 and, after its failure, emigrated with his wife and oldest son to the U.S., settling in New York, where he later volunteered to serve during the Civil War.2 His youngest son, William Walter Ludwig, was born in New York and, in 1894, married Sadie Rich Thompson, whose family had lived in the state for several generations. The couple had four sons born just a year apart, but each in a different town.3 In the early years of his service as a Baptist minister William Walter Ludwig moved from church to church and town to town. He was in Newark when Lloyd Ludwig, the second son, was born. In 1902 the senior Ludwig was called to the Borough Park Baptist Church in Brooklyn, and the family remained there until 1920.4

Lloyd Ludwig attended Manual Training High School in Brooklyn and then Colgate College in Hamilton, New York, graduating in 1917.5 By mid-May 1917 he was at the officers training camp at Madison Barracks in Sackets Harbor, New York.6 At some point in the summer of 1917 he applied for and was accepted by the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. On July 2, 1917, along with Guy Maynard Baldwin, Wendell Ellison Borncamp, Donald Swett Poler, and Donald Andrew Wilson, he went from Madison Barracks to Ithaca, New York, for aviation training at Cornell’s School of Military Aeronautics.7 Their class of sixteen men graduated August 25, 1917.8 They were among the twelve from the class who chose or were chosen for training in Italy and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment,” who sailed to England on the Carmania. The ship departed New York on September 18, 1917, sailing initially to Halifax. From there, as part of a convoy, the Carmania set out on September 21, 1917, to cross the Atlantic. The men had the good fortune to be travelling first class. They were evidently assigned to staterooms in alphabetical order, but some horse trading ensued. Ludwig “exchanged with another fellow so as to get into the same stateroom with Andy and Baldy.”9 “Baldy” was presumably Baldwin, and “Andy” was another Cornell ground school graduate, Robert Alexander Anderson.

During the voyage Ludwig had plenty of leisure to write in his diary, recording “our few duties as usual, Italian, calisthenics, boat drill, good meals, reading, walking and a little shuffleboard”10 Italian was taught by their shipmate, Fiorello La Guardia. The evenings were often whiled away with music. Ludwig’s fellow detachment members Anderson, Horace Wells, and Earl Adams were musicians. Also among the passengers was the famous violinist Albert Spalding, who gave several concerts. Ludwig was glad to encounter a high school friend, Stanley G. Saulnier, now a first lieutenant in the infantry.11 During the latter part of the voyage, once the Carmania had entered waters where German submarines were known to patrol, men from the detachment took turns on submarine watch. Ludwig noted on September 28, 1917, that “I went on duty at 5 this evening and will be on until tomorrow at the same time. I am in the first relief on the starboard end of the forward navigating bridge. It is very fascinating to sweep the seas and try to pick out every object right up to the horizon.” Fortunately, the Carmania encountered no U-boats.

On October 2, 1917, “When we woke up we found that we had dropped anchor in the Mersey right in front of our dock.” That morning at Liverpool the men boarded a train, and “About the middle of the morning a rumor started to spread around that we were not going to Italy but were to be sent to Oxford for 6 weeks more of ground school. At first nobody believed it, but it proved to be true.” Unlike some of his fellow detachment members, Ludwig does not mention being made unhappy by the change of plans, simply that they were “to be sent to Oxford under Capt. [John Warren] Swann’s charge. . . . We left for a fine trip thru a wonderful country about 5:30. . . . Along with about thirty others I went over to Christ Church College. We had dinner at 7:30 P.M. in a wonderful old hall.”

Either Ludwig did not write in his diary while he was in Oxford or, more likely, a section of the diary is missing. In any case, the rumored “6 weeks more of ground school” at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford turned out to be four; the authorities were scrambling to move the cadets along. At the beginning of November twenty of them were able to start flight training, but Ludwig was among the 129 who were assigned instead to the Harrowby Camp machine gun school near Grantham in Lincolnshire (according to the War Birds entry for November 6, 1917, one man, James Whitworth Stokes, stayed behind in Oxford to be operated on for appendicitis). During the first two weeks there they had an intensive course on the Vickers machine gun, at the end of which another group of men, this time fifty, went to training squadrons. Ludwig wrote on November 19, 1917, that “Andy and Baldy left for Wyton today. Was mighty sorry to see them go although it is fine luck for them. . . .” He had evidently been sharing sleeping quarters with them, but now “Our hut had to be all broken up and I went down to the hut with with Wilson, Poler, Borncamp, [George Atherton] Brader, [Hilary Baker] Rex, [Clark Brockway] Nichols [sic; sc. Nicholl], [Ralf Andrews] Crookston and [Burr Watkins] Leyson. We started our course on the Lewis [machine gun] today.” The next day “Started some agitation for a football game on Thanksgiving Day.”

Ludwig was evidently an enthusiastic and talented football player, and the game turned into a highlight of the festivities on November 29, 1917. Second Oxford detachment member and journalist Walter Chalaire described it as “a thriller—a real, live, honest-to-the-world football game between two teams composed of men who have recently played on the varsity teams of their respective colleges. . . . the throngs of British officers, nurses and men who witnessed the game were treated to a rare performance of forward passing, line bucking, punting and drop kicking. The intensity of the play may well be imagined from the final score, which stood: Unfits 9; Hardly Ables 7.”12 Ludwig played for the winning Unfits. “In the evening we had our Thanksgiving dinner—turkey, cranberry sauce & English attempt at ice cream. Had a lot of English officers as our guests and after dinner most of them and a lot of our fellows got pretty happy.”13

Ludwig goes on to note that “I spent the evening reading and writing,” and these sober activities may in part account for his good results the next day: “Had two more exams on the Lewis gun today—the last. I was quite lucky getting 296 out of a possible 300.” He also recorded that day getting “the good news that we would be posted to Squadron[s] on Monday. It looks as tho we’re going to a place called Marham Smeath, near Downham in Norfolk with Wilson, Poler, Brader, Borncamp, and [Melville Folsom] Webber.” And, indeed, on December 3, 1917, the six men, who would continue as a group as they progressed through their training postings, left Grantham for No. 51 Home Defense Squadron at Marham in Norfolk. No. 51, commanded at this time by Frederic Cecil Baker (“a mighty fine fellow”), was tasked with defending that part of England from Zeppelin raids; like other home defense squadrons, it also did its share of pilot instruction. Ludwig was billeted with Borncamp, Poler, and Webber at the vicarage, home of Harry Stanley Branscombe, vicar of Marham, “a very likeable gentleman and I am sure we are going to enjoy being here.”

The next day, December 4, 1917, was a red letter day for Ludwig: “The most important thing today, in fact in some ways the most important thing that has happened since I entered the army, was that I was up for my first flight this morning. I went up with Lieut. Hampton and was up for 23 minutes. It was great – far better, even, than I thought it could be and I enjoyed every second of it.” The same day also, however, brought the disappointing realization that: “All the machines here are FE2B’s and as none of them are dual control machines; we will not be able to learn to fly here.” Ludwig was philosophical: “ . . . we’ll have to make the best of it and the rides will give us a good foundation for later work.” His next day’s flight bore this out: “Had another good joy-flip today with Lt. [George William] Higgs, a Canadian. Was up for 50 minutes and before we came down he did some ‘stunts’ which were great. Did four Immelmans, several stalls, a spiral nose dive and a long sideslip. They certainly are great. Higgs is a mighty good chap as well as a fine pilot.”14 In a letter to William Henry Hoerrner, one of his Colgate professors, Ludwig describes sitting in the F.E.2b’s front seat: “All the machines here are of the pusher type and in these the observer is stuck out in the very nose of the machine and consequently all the sensations of flying are accentuated quite a little. You are perched out with nothing in front of you but the thin wall of the nacelle or body. I am glad to say that I haven’t been bothered in the least by dizziness or any other unpleasant sensations and some of the stunts, especially the ‘Immelman’ are considered pretty good tests of one’s ‘air legs’.”15

A few days later, Ludwig went with Poler to nearby Narborough Aerodrome where they had the opportunity to fly in a DH.6—a training aircraft that felt to Ludwig like “a steady slow bus” compared to the FE2b.16

On December 13, 1917, ten days after their arrival at Marham, Ludwig and Poler went to Mattishall, about twenty miles due east of Marham, where No. 51’s A flight was located.17 They remained there only a few days. On December 17, 1917, he and his fellow American cadets were sent on to No. 192 Night Training Squadron at Newmarket—journeying via Ely, whose cathedral was “the most wonderful I have yet seen.” No. 192 also flew F.E.2bs, but again the machines lacked dual controls, and, in any case, Ludwig notes, there were “practically no machines serviceable for flying,” so opportunities to fly were limited—a state of affairs to which the December weather also contributed. Distraction came in the form of an enjoyable Christmas leave spent in London with Borncamp. Not long after their return, they learned that they would shortly be reassigned; this meant returning to London—no hardship—“to get instruction to where we were to go.”18

The luck of the six American cadets had finally turned; they were about to commence real training.19 On December 31, 1917, “Left the Waterloo station at 9:35 for Gosport” on the south coast where they reported to the School of Special Flying, Fort Rowner, Gosport, “about 20 minutes ride from Portsmouth.” “Best of all is the fact that this is said to be the best flying school in England.” This was where Robert Raymond Smith-Barry had developed a training method for R.F.C. pilots that replaced seat-of-the-pants flying with theory and experience-based training, providing pupils with the knowledge and skills to, for example, get into and out of a spin. Smith-Barry had been able to take advantage of the two-seater Avro 504j, “a reliable aircraft with the handling characteristics of a single-seater fighter . . . [it] could thus be used to carry out all the aerobatics in his syllabus.”20 The School used Grange Aerodrome, an open area to the west of Gosport’s Forts Grange and Rowner; the students were quartered in the Fort Rowner barracks. “Don Poler and I have a room together with an English officer. The rooms are fine—each of us has a spring bed, mattress, blankets & sheets, a washstand, a table and a wicker arm chair. It really is almost like luxury after what we have been having. The mess appears to be very good.”21

Poor weather meant that Ludwig flew only briefly on New Year’s Day, but on January 2, 1918, serious instruction commenced. He “started flying soon after nine o’clock. . . . First tried flying straight, then tried a few simple things such as climbing and gliding. Before coming down Lt. Benson gave me a few stunts; 4 loops, 4 Immelman’s, etc. Was up for just 60 minute[s] in the morning. In the afternoon I was up for 40 minutes. Climbed up to 7500 to get above the clouds and tried doing some turns up there. Was pretty poor on them, especially at first. The Avro is so sensitive on the controls that it is not going to be easy to learn to fly it, but once we do we’ll be alright for almost anything.”22

The weather was on many days remarkably clement, given the time of year, and by mid-month, Ludwig had gotten in a great deal of dual flying. After two days of no flying due to snow and then rain, he was ready, on January 16, 1917, to fly solo. “I got along quite well—stayed up for 50 minutes and tried two loops. It was great to be up by oneself and enjoyed the feeling of freedom that one has at handling everything by oneself. I explored around the country a good bit; flew up the coast, over Fareham and Gosport and the surrounding country. My landing was not exceptionally good but Benson said that it was quite all right so I was delighted.” Ludwig built up confidence and on January 21, 1918, could write that “I was up for an hour and five minutes (solo). Got along quite well—did four loops”; in the afternoon, more loops and some side-slips. Two days later he “took the ‘Clip Wing’ up in the morning. This is quite ‘some’ machine and decidedly tricky. She is a little hard to land but on the whole is a fine bus to fly. I stunted her quite a little.” It is likely that the plane he flew that day was Avro 504j B4264, which, as part of experimentation with Avros at Gosport, had been fitted with short span, single bay (rather than the standard two bay) wings, reducing the total wing span (normally thirty-six feet) significantly.22a

About three weeks later, on February 12, 1918, he recorded that “In the afternoon went up in the S.E.5 and got away with it all right.” Going from an Avro to an S.E.5 was a major step, and it is not clear whether he was “got away” with something unauthorized or simply with making the transition to an advanced machine. The next day he made a cross country flight to Shoreham, nearly forty miles to the east (he overshot due to clouds, but eventually located his objective). He was perhaps making the cross-country flight required for graduation from the initial stage of R.F.C. training—a prerequisite for a commission as a first lieutenant. Borncamp and Brader are recorded as having graduated on February 15, 1918, and it is likely that Ludwig also graduated that day, or perhaps earlier; the recommendation for his commission (as well as Poler’s) was forwarded by Pershing to Washington on February 16, 1918 (the confirming cable is dated March 1, 1918).23

When not flying, studying, or reading and writing letters, Ludwig and his compatriots got to know the area around Gosport and gradually developed quite an active social life. Ludwig and Wilson played tourist on Lord Nelson’s H.M.S. Victory, moored at Portsmouth. Not long afterward they got to know a number of American naval and medical officers, and through them residents of the Glenlyon Hotel in Southsea, where they dined and danced. There were also the cinema (D. W. Griffiths’ “Intolerance”) and plays (“The Better Ole,” “Maid of the Mountains,” “Zig-Zag”). Relations between the cadets and the Gosport instructors were clearly very cordial. After a sumptuous dinner with an American naval officer, Henry Emil Quenstedt, on the U.S.S. Gargoyle the evening of January 27, 1918, Borncamp, Ludwig, and their instructor, Lt. Benson, “stopped at Benson’s for a while after coming back and had a very nice time. Mrs. Benson played for us. . . .” On February 11, 1918, in a show of appreciation, “the six of us Americans . . . gave a dinner for our instructors at the Queens,” an elegant Edwardian hotel in Southsea. “Capt. Smart, Capt. Watson, Lt. Benson, Lt. Long and Lt. Holbrow were there we had a fine dinner and fine time and went into the Hippodrome afterwards.”24

Ludwig noted in his diary on Thursday, February 14, 1918, that he “Heard we were going to leave here after this week.”24a And, indeed, he, Poler and Wilson (and presumably Borncamp, Brader and Webber) were soon posted to No. 28 Training Squadron at Castle Bromwich, near Birmingham; they were to train on S.E5s. Ludwig was already slightly familiar with S.E.5s from his flight on February 12, 1918, and found he liked them. “They are wonderful for stunting; very strong; have a beautiful engine and fly very easily—at least I think so. The fastest I have travelled in one so far is 160 M. Per hour.”25 He apparently took an S.E.5 up for the first time at Castle Bromwich on February 25, 1918 and, as he wrote his mother, had “quite an interesting experience. . . . the country was entirely new to me. I was up several thousand feet doing some stunts when quite a heavy ground mist came up. At the speed one travels it does not take long to cover a good deal of ground and by the time I was down to where I could see anything clearly I was completely lost.” He eventually set down in a farmer’s field (“much better than many airdromes I have seen”) near a town, and “What was my delight when upon inquiry I found out that the town was Stratford-on-Avon.” He phoned his squadron, got lunch, and enjoyed playing tourist before refueling and setting off back to Castle Bromwich around 4:30. “When I got back and told Capt. [Arthur] Coningham, our squadron commander, about my experience he was tickled to death especially when I told him that after finishing with my business I went around and saw the place there ‘Bill’ Shakespeare was born. The captain is a splendid fellow and ‘some’ pilot.”26

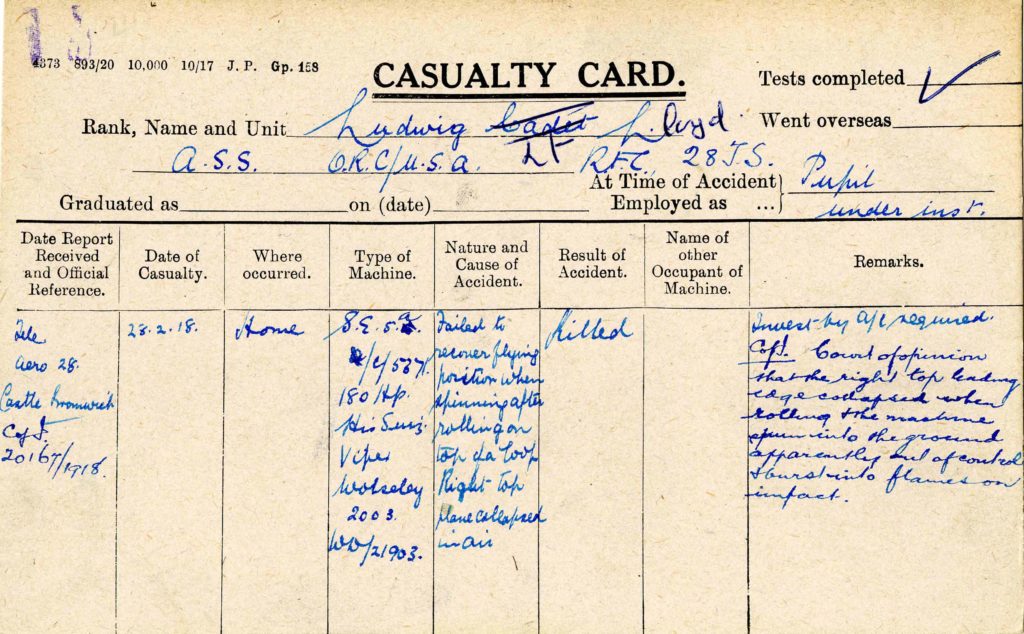

On February 28, 1918, the day after he wrote his mother about his unplanned trip to Stratford, Ludwig, Poler, and Wilson practiced flying for about an hour. Wilson recalled that “It was snowing hard—a regular blizzard, but [Ludwig] stayed up after we landed. Finally he came down out of a great flurry of snow, and, after warming himself and talking to us, while the airplane was looked after, he decided to go up for another short ‘flip’.”27 He was flying S.E.5a C5371. While stunting he “failed to recover flying position when spinning after rolling on top of a loop. Right top plane collapsed in air.”28 The aircraft was now out of control and spun into the ground; Ludwig was killed. The next day Ludwig’s father received a telegram notifying him of his son’s death.29

Ludwig was apparently initially interred in a church cemetery in Castle Bromwich.30 It became U.S. policy that American war dead could be repatriated at the request of the family, but transport was not feasible until after the cessation of hostilities. The Ludwig family chose to have their son returned to them, and his was one of fifty-seven bodies of military deceased transported on the Northern Pacific from Liverpool to Hoboken in late October 1920.31 The bodies of Ludwig’s fellow second Oxford detachment members Chester Albert Pudrith and Elwood D. Stanbery, both of whom had also been killed in flying training accidents in England, were also among the fifty-seven. Services were held for Ludwig on November 13, 1920, at the Borough Park Baptist Church in Brooklyn where his father had been pastor; his final resting place was Brooklyn’s Greenwood Cemetery.32

mrsmcq June 20, 2019

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

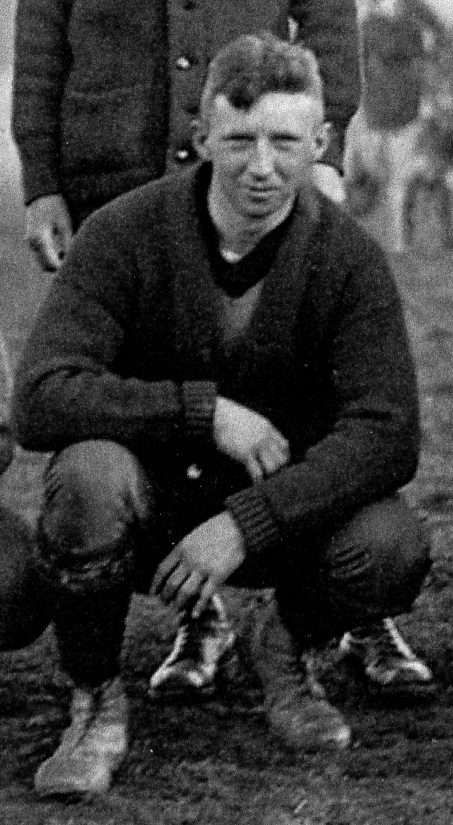

1 Ludwig’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, New Jersey, Births and Christenings Index, 1660–1931, record for Lloyd Ludwig. His place and date of death are taken from “Ludwig, L. (Lloyd).” I am grateful to Mike O’Neal for sharing information, documents, and photos related to Lloyd Ludwig. See also O’Neal’s account of Ludwig, “A Short Time Across the Pond.” The photo is a detail from a group photo of Ludwig’s ground school class at Cornell.

2 “Young Aviator Fought Autocracy, as Did His German Grandsire.”

3 On the family, see documents available at Ancestry.com.

4 “Former Brooklyn Pastor Retires from N. J. Church.”

5 See “Lloyd Ludwig Killed in Airplane Accident.”

6 See Ludwig’s diary entry for December 31, 1917, to which he appends a “Resume of events since entering the service.”

7 “Cadets Enjoy Their Usual Sunday Rest.”

8 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

9 Ludwig, diary entry for September 18, 1917. I should note that in quoting from the diary in what follows I have silently corrected what appear to be minor transcription errors. Further quotations from the diary will be footnoted only when the date would otherwise not be evident.

10 Ludwig, diary entry for September 25, 1917.

11 The transcript of Ludwig’s diary renders this name “Lauliner” (September 19, 1917) and Laulnier (September 29, 1917), but the correct spelling is almost certainly “Saulnier.”

12 Chalaire, “Thanksgiving Day with the Aviators Abroad.”

13 Ludwig, diary entry for November 29, 1917.

14 On Higgs, see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for George William Higgs..

15 “Letters from Lloyd Ludwig, Colgate Alumnus, Describe Training in England.” It appears that an error has been made in reproducing the place and date of the letter, given as “Grantham, Dec. 17, 1917.” Internal evidence makes clear it was written on December 8, 1917, while Ludwig was with No. 51 H.D.S. at Marham.

16 Ludwig, diary entry for December 11, 1917.

17 See Ludwig’s diary entry for that day.

18 Ludwig, diary entry for December 29, 1917.

19 Ludwig in his diary and Poler in his recollections (see Sloan & Hocutt, “One of the ‘War Birds’”) refer to six cadets training together, and Ludwig’s initial list (November 30, 1917) includes Webber. He does not mention Webber after mid-December, so the evidence that Webber’s training postings were the same as Ludwig’s after that is indirect.

20 Wise, Canadian Airmen and the First World War, p 105.

21 Ludwig, diary entry for December 31, 1917.

22 His instructor was probably Reginald John Bedlington Benson; see “Gosport School of Special Flying, names of instructors?” and The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Reginald John Bedlington Benson.

22a I am grateful to Aerodrome forum members for suggesting that Ludwig’s plane was B4264. See “Clip Wing”; see also Bruce, “The Avro 504,” p. 84.

23 Cablegrams 612-S and 852-R. Borncamp’s and Brader’s graduations are recorded in their R.A.F. service records. For some reason, their commission recommendations were not forwarded until mid-March (cablegram 739-S).

24 The guests were probably Harry George Smart, Donald Watson, Reginald John Bedlington Benson, Walter Brian Long, and William Gerald Holbrow. See “Gosport School of Special Flying, names of instructors?”.

24a His diary entry for February 14, 1918, is the last entry in the diary transcript.

25 See Ludwig’s letter of February 27, 1918, to his mother reproduced in “Letters from Lloyd Ludwig.”

26 Ibid.

27 Letter from Donald A. Wilson dated February 28, 1918, to Ludwig’s brother, William Walter Ludwig, reproduced in “Letters from Lloyd Ludwig.”

28 Note on casualty card, “Ludwig, L. (Lloyd).”

29 “Lloyd Ludwig Killed in Airplane Accident.”

30 This information appears in a note at the end of the transcription of Ludwig’s diary.

31 See Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Lloyd Ludwig.

32 “Lt. Lloyd Ludwig’s Funeral Saturday.”