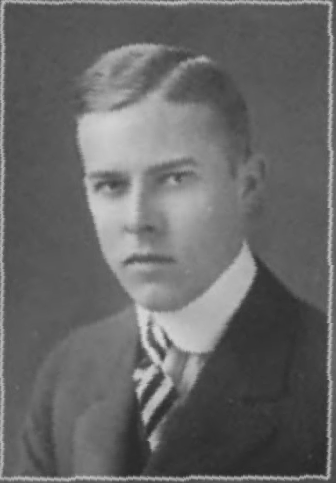

(Athens, Georgia, May 25, 1894 – Boscombe Down, England, May 9, 1918).1

The Griffith family had lived in Georgia for several generations, but Griffith’s mother, who died when he was about six, was a northerner, from Brooklyn. Griffith was the middle of three sons; his father worked in the insurance industry.2

Griffith attended the University of Georgia, graduating with a B.S. in 1915. I have found no record of his activity following his graduation until he enlisted in the reserve corps in April 1917. He was subsequently assigned to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and attended ground school at Ohio State University, graduating September 1, 1917.3

Along with most of his O.S.U. classmates, Griffith chose or was chosen for training in Italy and was thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed on the Carmania, departing New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departing Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University.

On November 3, 1917, most of the detachment, including Griffith, went to Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend gunnery school at Harrowby Camp.4 Fifty of the men departed on November 19, 1917, for flying schools; Griffith was among the men who remained at Grantham until early December and completed two two-week machine gun courses, the first on the Vickers, the second on the Lewis machine gun.

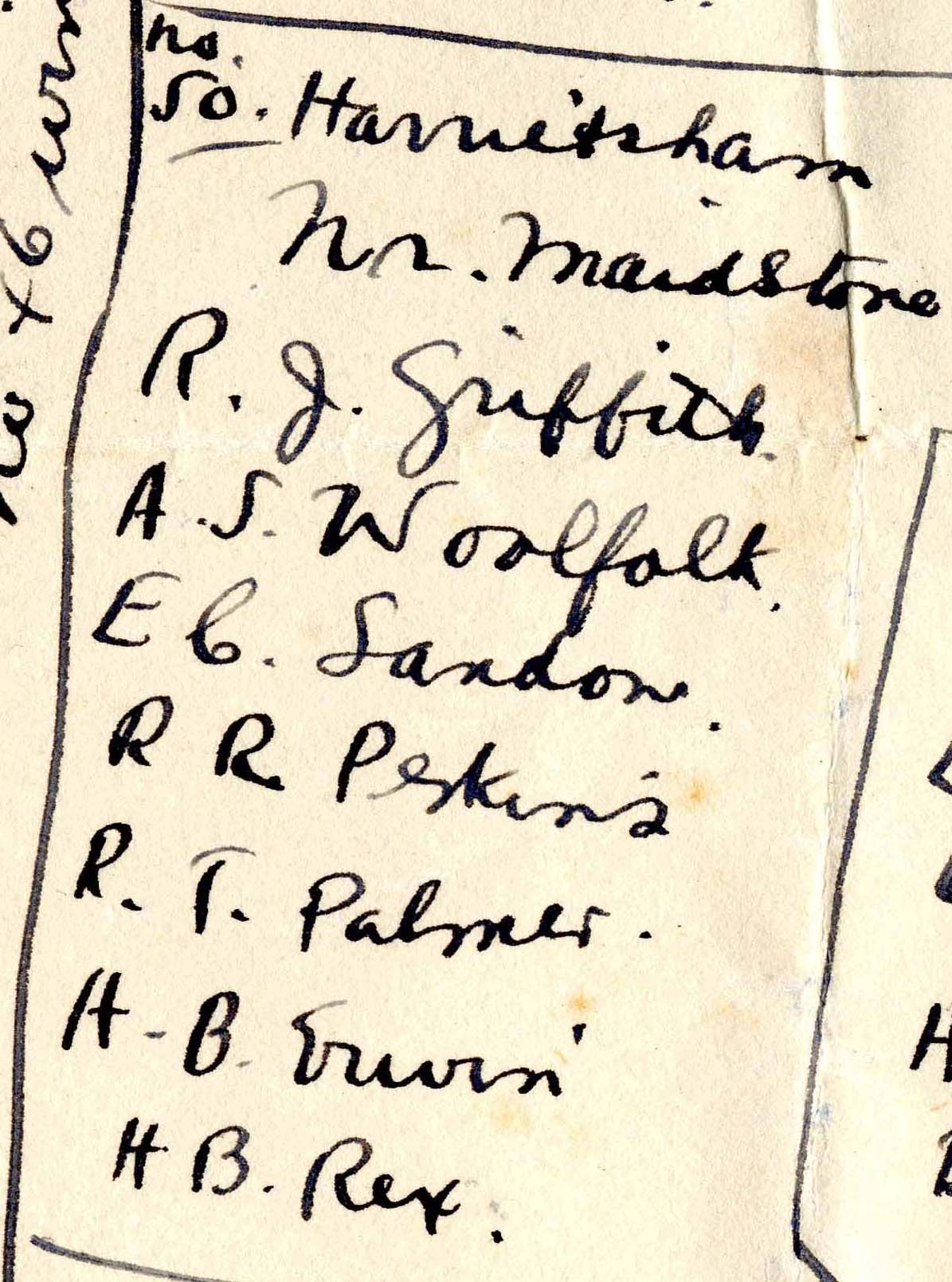

On December 3, 1917, the remaining men at Grantham were posted to flying training squadrons. Griffith, along with Harrison Barbour Irwin, Edward Carter Landon, Robert Thomas Palmer, Pryor Richardson Perkins, Hilary Baker Rex, and Albert Sidney Woolfolk (all of whom, except Rex, had been in his O.S.U. ground school class), was assigned to No. 50 Squadron, a home defense squadron.5 The squadron’s available aircraft at the turn of the year included the B.E.2e and the A.W. FK.8, both two-seaters used for reconnaissance and bombing, and the B.E.12b, a single-seater night fighter; No. 50 had no dual-control machines that could be used for training when the men arrived.6 The squadron’s headquarters was at Harrietsham, near Maidstone, in Kent, but its flights were at this time detached to Detling and Bekesbourne. Landon, Palmer, Perkins, and Rex were assigned to B flight at Detling, while Griffith, along with Irwin and Woolfolk, went to C flight at Bekesbourne near Canterbury.6a It is evident from Rex’s diary and Palmer’s pilot’s flying log book and one of his letters that they were able to get in some flying at Detling, though they had no formal instruction; it seems likely that the experience of Griffith, Irwin, and Woolfolk at Bekesbourne was similar.

Griffith’s R.A.F. service record indicates he went from No. 50 Squadron to “T.D.S. Boscombe Down” in Wiltshire on January 26, 1918.7 This was No. 6 Training Depot Station, where the pilots could do their initial training on on DH.6s (a two-seater plane designed for training purposes) or on Avros or B.E.2c’s or B.E.2e’s, and then move on to D.H.4s and D.H.9s, as well as B.E.12s, FK.8s and perhaps R.E.8s; the goal was to produce observation and bomber rather than scout pilots.8 Griffith apparently remained at Boscombe Down throughout his training. He was evidently there when pilots detached from the U.S. 148th Aero Squadron arrived at Boscombe Down for training in April and must have enjoyed the companionship of these fellow Americans; one of those pilots, Lawrence Leland Smart, refers to Griffith as one “of our group.”9

Griffith’s progress was such that on March 20, 1918, Pershing forwarded the recommendation that he be commissioned a first lieutenant; the cable confirming the appointment is dated April 2, 1918.10 That same day, according to a letter dated written by Edward Russell Moore, Griffith was one of a group making a cross-country flight: “Four of my bunch, including myself, planned a 350-mile across country last Tuesday. [Phillips Merrill] Payson and I made the course, [George Clark] Sherman got lost in the clouds about half an hour from home on the start and Griffith got lost over Ipswich. The most distant point was Elmswell. . . . Grif came home the next day at noon and all returned safe. The commanding officer is keen on such stunts so needless to say we won a little recognition.”10a

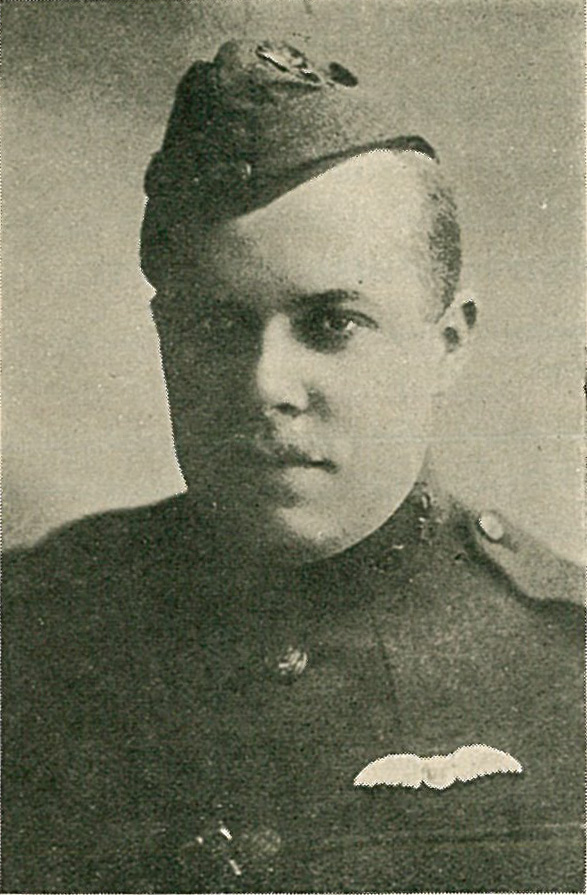

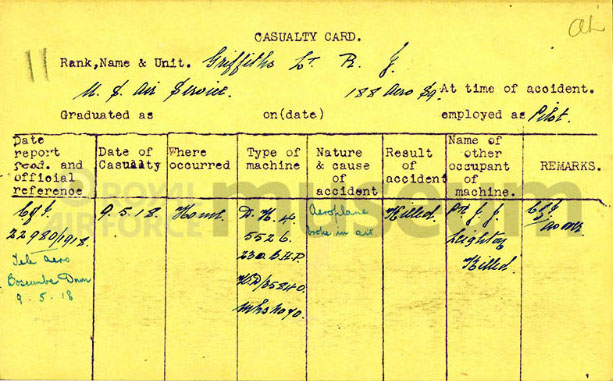

Just over a month later, on May 9, 1918, Griffith was flying Airco DH.4 B5526 with John Joseph Leighton from the American 188th Aero Squadron, which was training at Boscombe Down, as his crew.10b Griffith’s fellow second Oxford detachment member William Ludwig Deetjen, stationed nearby at Stonehenge, was walking home that afternoon and “watched a deH9 [sic] flying. Suddenly with a deafening sound the wings folded up and left the buss. The fuselage, with engine full on, made a spin or two and then came down to earth hell bent for election. ’Twas an awful roar that you could hear for miles. I’ll bet it reached 260 M.P.H. Later it developed that Bob Griffith of our detachment was pilot. He had an American A.M. with him. Needless to say both were badly messed up. That makes at least 16 of our original 150 gone west.”11 The War Birds entry for May 13, 1918, also states that Griffith had been flying a DH.9; perhaps Deetjen was the source for this error. In any case, the two planes are visually very similar.

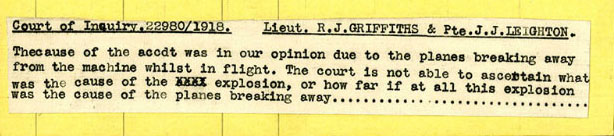

A court of inquiry was held, but the cause of the fatal accident remained obscure: “The cause of the accident was in our opinion due to the planes breaking away from the machine whilst in flight. The court is not able to ascertain what was the cause of the explosion, or how far if at all this explosion was the cause of the planes breaking away.”12 Smart recalls that “No one ever found the cause of this incident; the colonel gave orders to ground all D.H.4’s and D.H.9’s until they had been given a thorough inspection from prop to rudder.”13

Griffith was buried in the cemetery in nearby Amesbury; after the war his body was exhumed and reburied at Brookwood American Military Cemetery.14

Griffith’s crew, John Joseph “Jack” Leighton had been born in Ballina, County Mayo, Ireland, June 19, 1891.15 He emigrated with a sister to the United States in 1911, and it appears that other members of his family joined him in Philadelphia.16 He was working as an auto mechanic and supporting his parents when he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917 (he was still an alien at the time). At some point he was assigned to the 188th U.S. Aero, which had formed at Kelly Field in Texas in November 1917. The squadron sailed to England in March 1918. At the end of that month they were posted to Boscombe Down for training in maintenance of DH.4s, DH.6’s, and DH.9s.17

The squadron history for the 188th preserved in Gorrell has an account of the fatal accident that is somewhat at variance with Deetjen’s description: “. . . when about five thousand feet in the air, the panels on one side [of the plane] collapsed. Private Leighton was seen to climb out onto the remaining wing in an endeavor to balance the machine. No sooner had he done this than the wing he was on was torn loose and he fell with it until only a short distance from the ground, when he jumped presumably for a haystack which he missed by a few yards.”18

Leighton was buried in England; his body was apparently exhumed and returned to the U.S. after the war, although his current resting place is not public knowledge.

mrsmcq August 11, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Griffith’s date of birth is taken from Ancestry.com, Georgia, World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919, record for Robort [sic] J Griffith. The photo is a detail from a group photo of his ground school class.

2 Information on Griffith’s descent is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com. On his siblings and his father’s business, see Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Arthur Griffith.

3 For Griffith’s graduation year and degree, see The University of Georgia, Announcement of the University of Georgia for the Session of 1916– 1917, p. 51. On his reserve corps enlistment date, see Ancestry.com, Georgia, World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919, record for Robort [sic] J Griffith. For his ground school attendance, see “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

4 There is a photo on p. 49 of Milnor’s photo album originally captioned “Castle Griffiths Ham”; the caption has been modified by a later hand to read, in part, “R J Griffiths.” However, the man pictured is almost certainly Edward Addison Griffiths, not Robert Jenkins Griffith.

5 See Foss’s list of “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers.

6 On the planes used at 50, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 408. On there being no training planes, see Rex, World War I Diary, entry for December 16, 1917.

6a Rex, World War I Diary, entry for December 5, 1917.

7 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Robert J. Griffith.

8 On 6 T.D.S. and the planes used, see the November 25, 2006, contribution by mickdavis at “Introduction and new Question TDStations,” as well as Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 294.

9 Smart, The Hawks that Guided the Guns, p. 18.

10 Cables 756-S and 1028-R.

10a Moore’s letter, dated April 7, 1918, is reproduced in “Letters from Soldiers” (May 23, 1918).

10b For the plane’s type and serial number, see “Griffiths, R.J. (Robert J.).”

11 Deetjen, Diary, May 9, 1918.

12 The report is pasted onto the verso of the casualty card, “Griffiths, R.J. (Robert J.).”

13 Smart, The Hawks that Guided the Guns, p. 18.

14 See the Georgia World War I service card for Griffith, cited above, which gives his initial place of burial. The National Archives, UK, has a record entry for a document held at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Center described as “Amesbury: to exhume corpse of Robert J Griffith and convey it to Brookwood,” dated 1929. And see “Robert J. Griffith.”

15 See Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for John Joseph Leighton; other documents give different dates.

16 Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1800-1962, record for Jack Leighton.

17 “188th Aero Squadron.”

18 Ibid., p. 237 (2).