(Portland, Maine, August 9, 1892 – Portland, Maine, June 30, 1977) 1

Oxford ✯ Grantham, Boscombe Down, Turnberry ✯ No. 55 Squadron I.A.F. ✯ With the 166th Aero Squadron

Payson came from a prominent and well-to-do Maine family. His Puritan ancestor, Edward Payson, emigrated from Essex, England, in the 1630s and settled in Massachusetts. Edward’s son Samuel married Mary Phillips, and her last name was used as a first name in the next and some subsequent generations.2 Samuel’s descendants included a number of Harvard graduates and prominent clergymen in the Congregational Church. His great-grandson, Edward Payson, Phillips Merrill Payson’s great-grandfather, moved to Maine, where all his children were born; the sons, rather than continuing the clerical line, went into law, business, and banking.3 Henry Martyn Payson founded the investment firm H. M. Payson; Henry Martyn’s nephew, Charles Henry Payson, became president upon the founder’s retirement in 1886.4 In the same year Charles Henry Payson married Margaret Meta Merrill. Phillips Merrill Payson—who went by “Pat”—was their second son and the third of four children; the older son died in infancy.

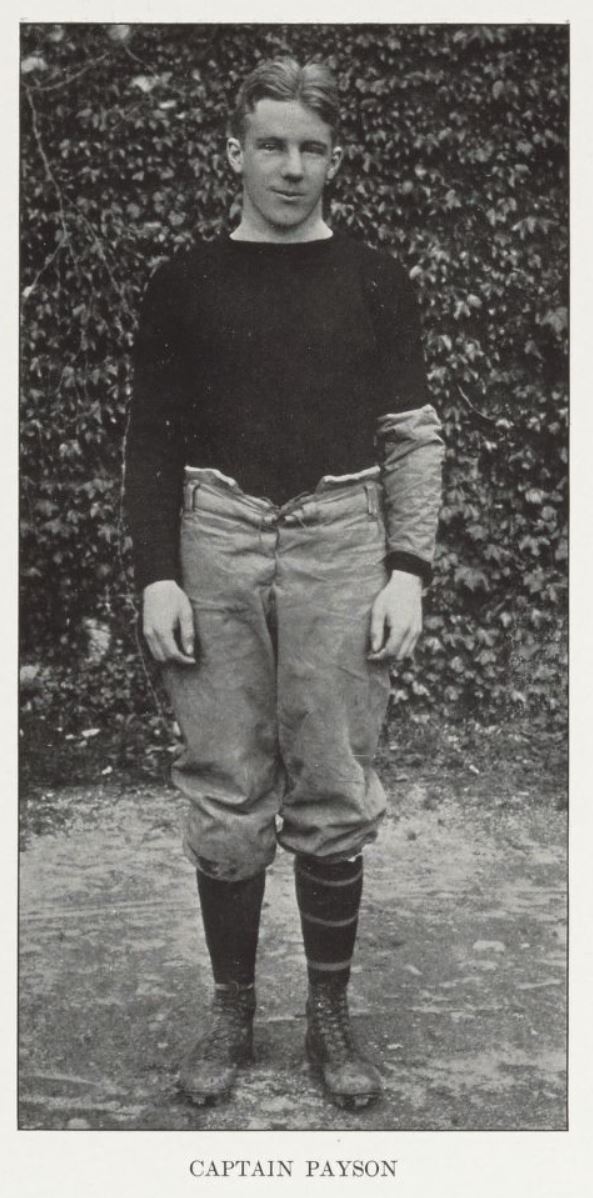

Payson attended St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, before entering Williams College in western Massachusetts with the class of 1915. In his freshman year he distinguished himself as a football player. His brief withdrawal from college due to illness meant that when he returned he was a member of the class of 1916. In the fall of 1913 he was elected captain of the 1914 football team, and, in general, he distinguished himself as an athlete.5

After graduation Payson spent ten months as a private in the cavalry of the Ohio National Guard and was for some of the time on the Mexican border in connection with the Mexican Punitive Expedition—it is not evident why he was with the Ohio rather than the Maine National Guard.6 On his return to Maine, he worked briefly as a bonds salesman for H. M. Payson Co., but soon after the U.S. entered the war, applied to and was accepted for the aviation corps.7 He attended ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at M.I.T. and was one of a group of eight men who are recorded as having graduated September 1, 1917.8 Of those eight, six—Payson, Leo McCarthy, John Lavalle, Andrew Joseph Shannon, George Dana Spear, and Perley Melbourne Stoughton—chose or were chosen for training in Italy, and these six were among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They left New York September 18, 1917, and arrived at Liverpool October 2, 1917.

Immediately on disembarking at Liverpool, the men were informed that they were not going to Italy, but were to remain in England where they would attend ground school (again). They boarded a train for Oxford and were enrolled at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University, where another, smaller, group of American cadets, the “first Oxford detachment,” was already ensconced. Thus the day after landing in England, Payson ran into a friend from Williams College, Paul Stuart Winslow of the first Oxford detachment, who recalled in his diary for October 3, 1917, that “I turned around and saw Pay [sic] Payson the captain and full back of the Williams team in 1911 . . . a great boy . . . and we talked for a long time—rehashing the old days.”9

The 150 men were divided into two groups, with ninety of them assigned rooms in Christ Church College in the charge of Elliott White Springs, and the remaining sixty in The Queen’s College under William Ludwig Deetjen. Though initially disappointed that they would not see sunny Italy, the men quickly became reconciled to the change and enjoyed England in the autumn. Having arrived too late for the start of that week’s classes, the men were free to settle in and explore Oxford and surroundings, and even once they started classes on October 8, 1917, because it was their second time going through much of the material, they did not have to put much effort into studying. On the second day of classes, Payson joined Deetjen, Joseph Frederick Stillman, Donald Swett Poler, and coxswain Donald Elsworth Carlton for “quite a workout on the river today. Formed a 4 oared crew from our detachment and rowed on the Thames.”10

Whether Payson was initially in Queen’s—as his palling around with Deetjen would suggest—or Christ Church I cannot determine, but during the latter part of October, he and Deetjen shared a room at Exeter College with Conrad Henry Matthiessen and Joseph Ralph Sandford, “all Tech men,” i.e., all men who had been at M.I.T. for ground school.11 The change of lodging came about when bibulous celebrations, mainly by the men of the first Oxford detachment, exceeded what the commandant of the Oxford S.M.A. felt was permissible, prompting him to insist that all the American be segregated into a single college, Exeter.

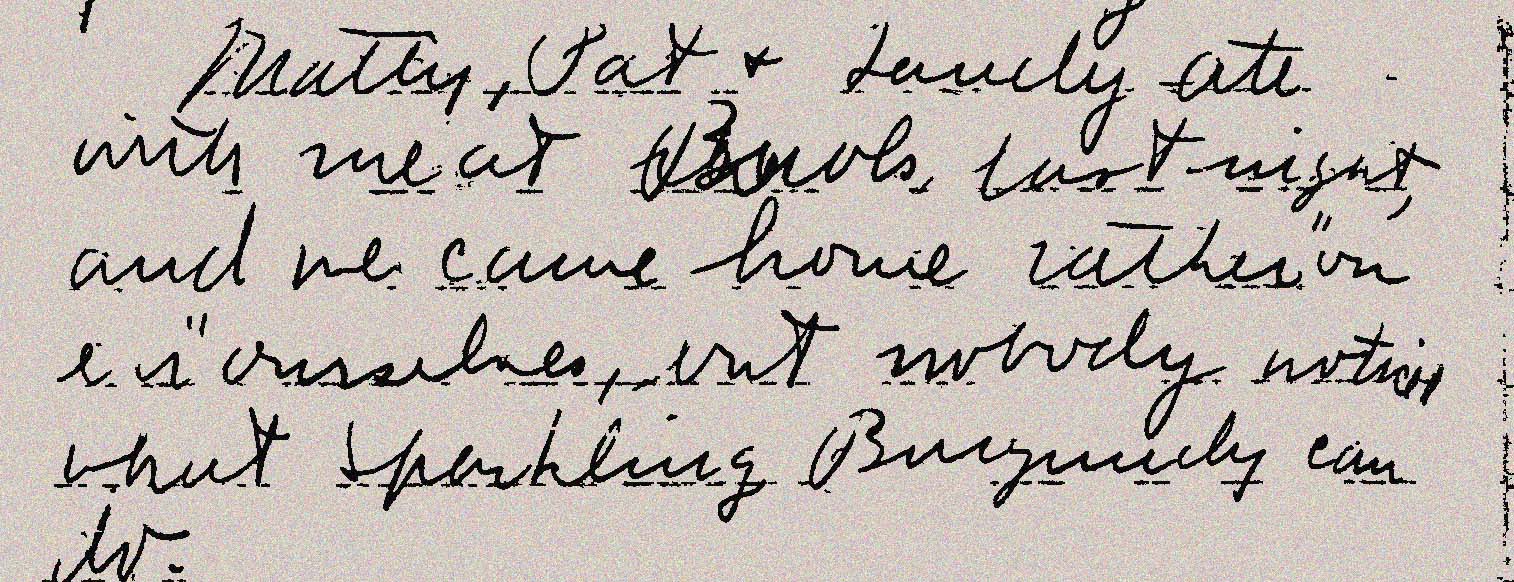

Some members of the second Oxford detachment had also been involved. Payson, Deetjen, Sandford, and Matthiessen were not among them, although they had that evening (Saturday, October 20, 1917) come “home rather ‘on air’” after supper at Buol’s.12

The following Saturday Deetjen recorded in his diary that “We went out on the river today, and I stroked our crew of Payson, [Harry Adam] Schlotzhauer, Stillman & [Alexander Miguel] Roberts coxswain. We never knew when we left Exeter that we were in for a final race. Well we just naturally pulled the bottom out of the river and won by two boat lengths from Corpus Christi. We were given passes tonight as a reward.” By this date the men were taking exams and hearing contradictory rumors about their future. On the last day of October, they heard that they would be another four weeks at Oxford, but the next day that “that 130 of us were going to Grantham Gunnery School in Lincolnshire.”13

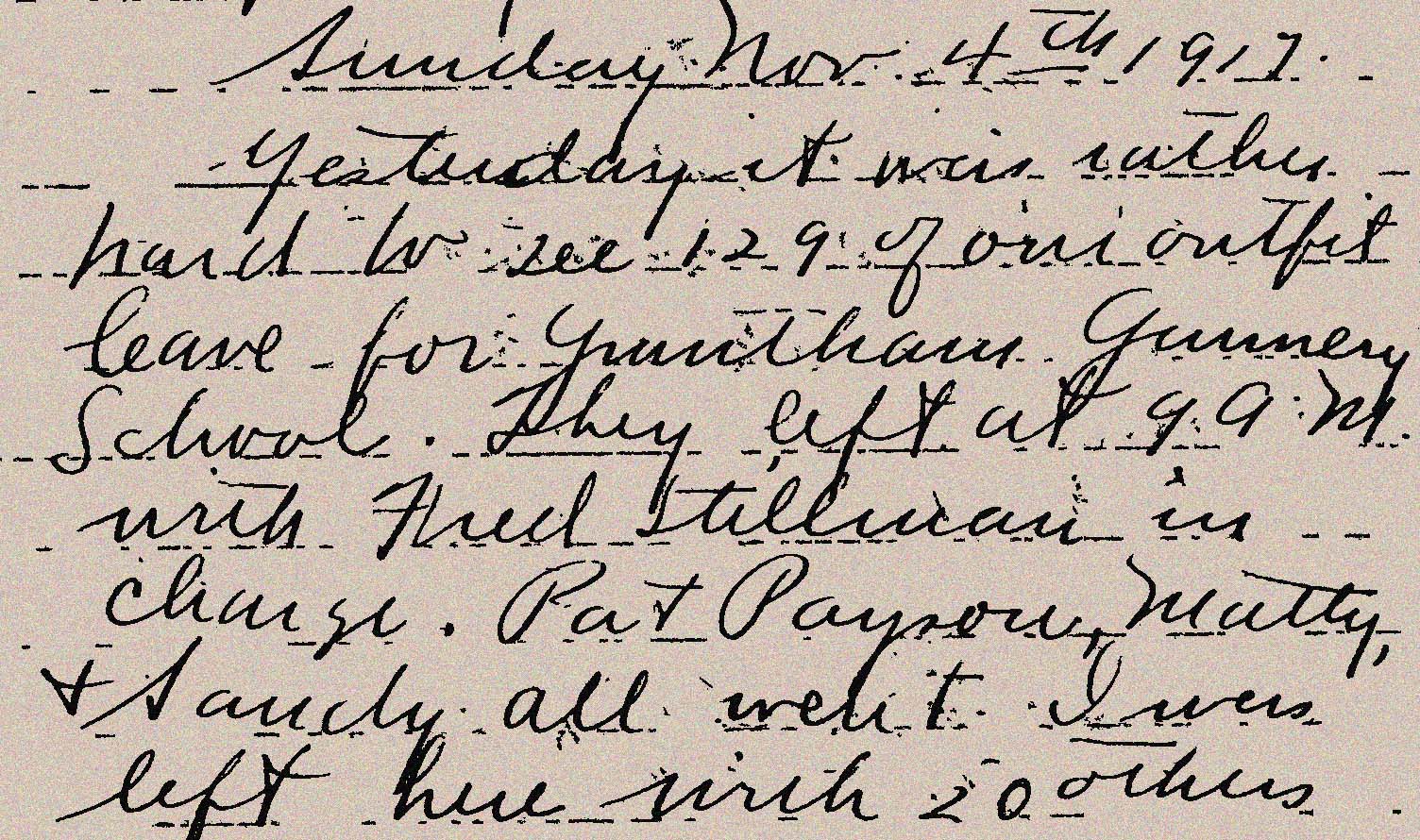

The latter turned out to be true. Twenty men were selected to go to Stamford to begin flying training, but the remaining men (less James Whitworth Stokes, who remained in Oxford for an operation) set out by train on November 3, 1917, for Harrowby Camp, a machine gun school near Grantham; Deetjen went to Stamford, but his Exeter roommates, including Payson, departed for Grantham.

Grantham, Boscombe Down, Turnberry

At Harrowby Camp the men initially attended a two-week course on the Vickers machine gun. A photo kept by Joseph Kirkbride Milnor and captioned “My Squad – Grantham” includes Payson, along with Thomas Welch Blackburn, Leonard Joseph Desson, Walter Ferguson Halley, Harrison Barbour Irwin, Wilbur Carleton Suiter, and Albert Elston Weaver.14 Midway through November 1917 it was learned that there were openings at training squadrons for fifty of the men. While Desson and Milnor, who were among the lucky fifty, departed on November 19, 1917, Payson and the others remained and commenced another two-week course, this time on the Lewis machine gun.

The highlight of their time at Grantham was Thanksgiving. Second Oxford detachment member Walter Chalaire, a journalist for the New York Herald in civilian life, wrote an article about the day (November 29, 1917) that appeared in a number of newspapers: “The big party was a reunion as well as a Thanksgiving day celebration. . . . The men who had already been posted to squadrons came in from all over England. . . . At 3 o’clock the curtain raiser was staged . . . a real live, honest-to-the-world football game between two teams composed of men who have recently played on the varsity teams of their respective colleges. . . . The intensity of the play may well be imagined from the final score, which stood: Unfits 9; Hardly Ables, 7.” According to Chalaire, Payson, who captained the Hardly Ables, “blames the war rations for the condition and defeat of his team, while ‘Temp’ [Temple Paul Hardin] attributes the success of the Unfits to the same thing.”15 A photo taken of players that day includes Payson. Although the names of the men from the winning team are known, there is no record the men who played with Payson beyond Edward Addison Griffiths.

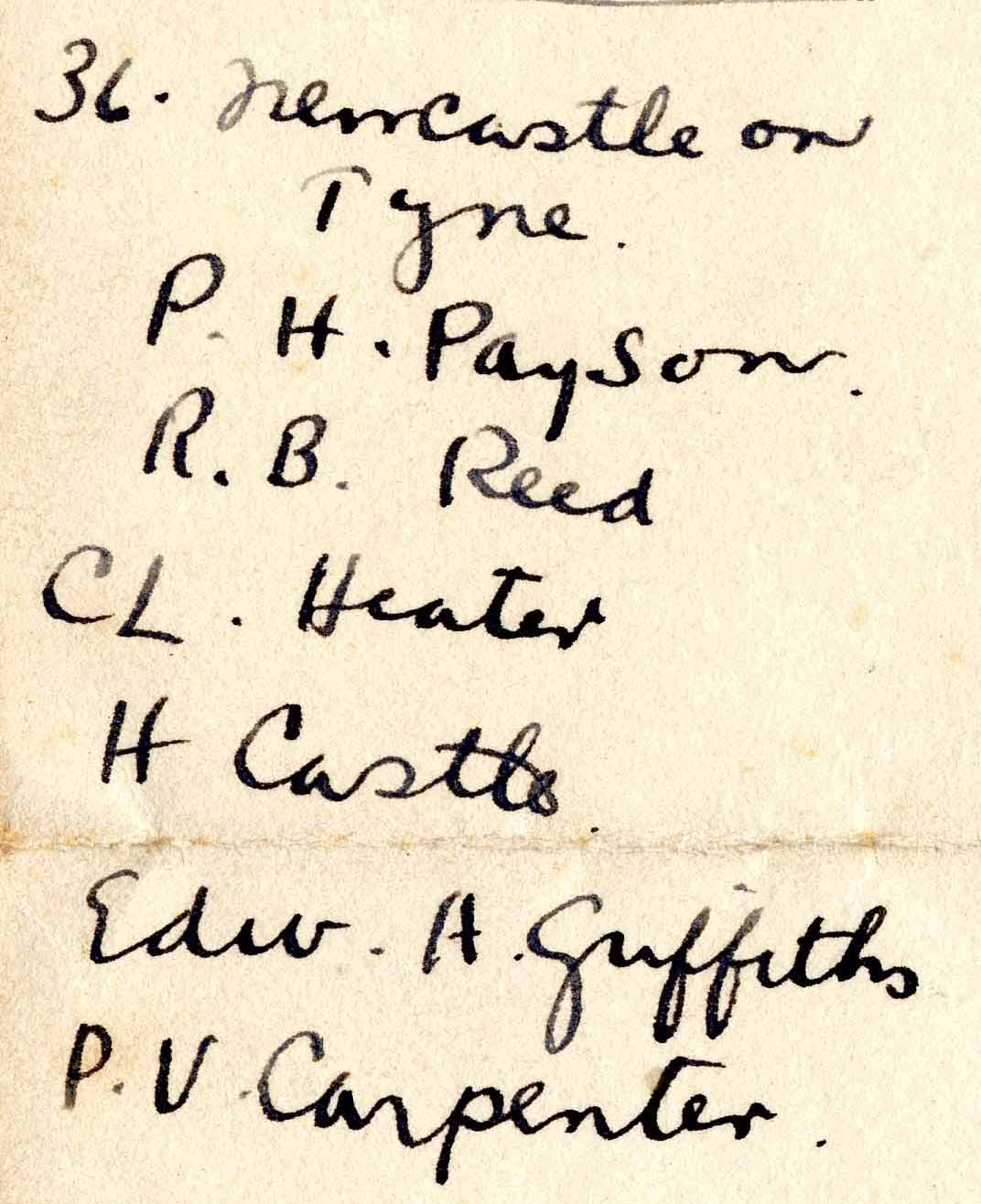

A few days later, on December 3, 1917, the Grantham men finally departed for flying squadrons. Payson, along with Paul Vincent Carpenter, Harvard DeHart Castle, Griffiths, Charles Louis Heater, and Richard Brumback Reed, was assigned to No. 36 Squadron. 36 was a home defense squadron flying F.E.2b’s and F.E.2d’s; based in Newcastle, it had detachments at Seaton Carew, Ashington, and Hylton.16 While most of the men assigned to other squadrons actually began training, the men assigned to 36 Squadron found, according to Heater, that “There was little flying activity . . . although we got a couple of short rides in the F.E.2b early British machines. . . . No instruction was given us.”17 This is corroborated by Castle, who early in the new year “said their crowd had had no instruction thus far; they were just marking time and fed up.”18 A visit to Edinburgh perhaps somewhat relieved the tedium. Of Christmas day there Deetjen wrote in his diary: “That evening I ran into Pat Payson, Castle and Griffith [sic; sc. Griffiths]. You can imagine the happy meeting between Pat & yours truly. . . . We all had dinner & movies & a good supper together. Next day was spent with the same bunch. . . .”19

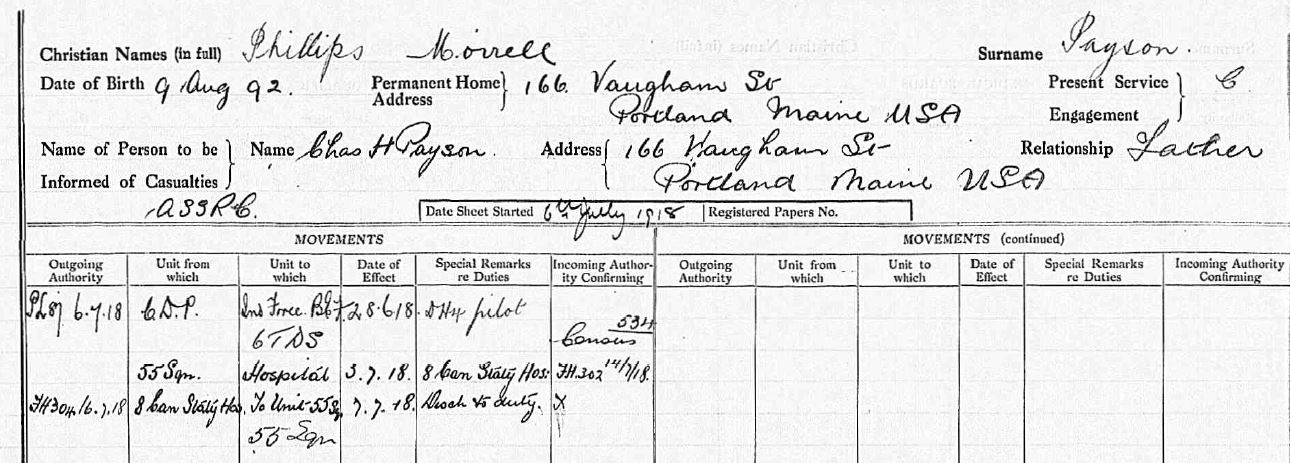

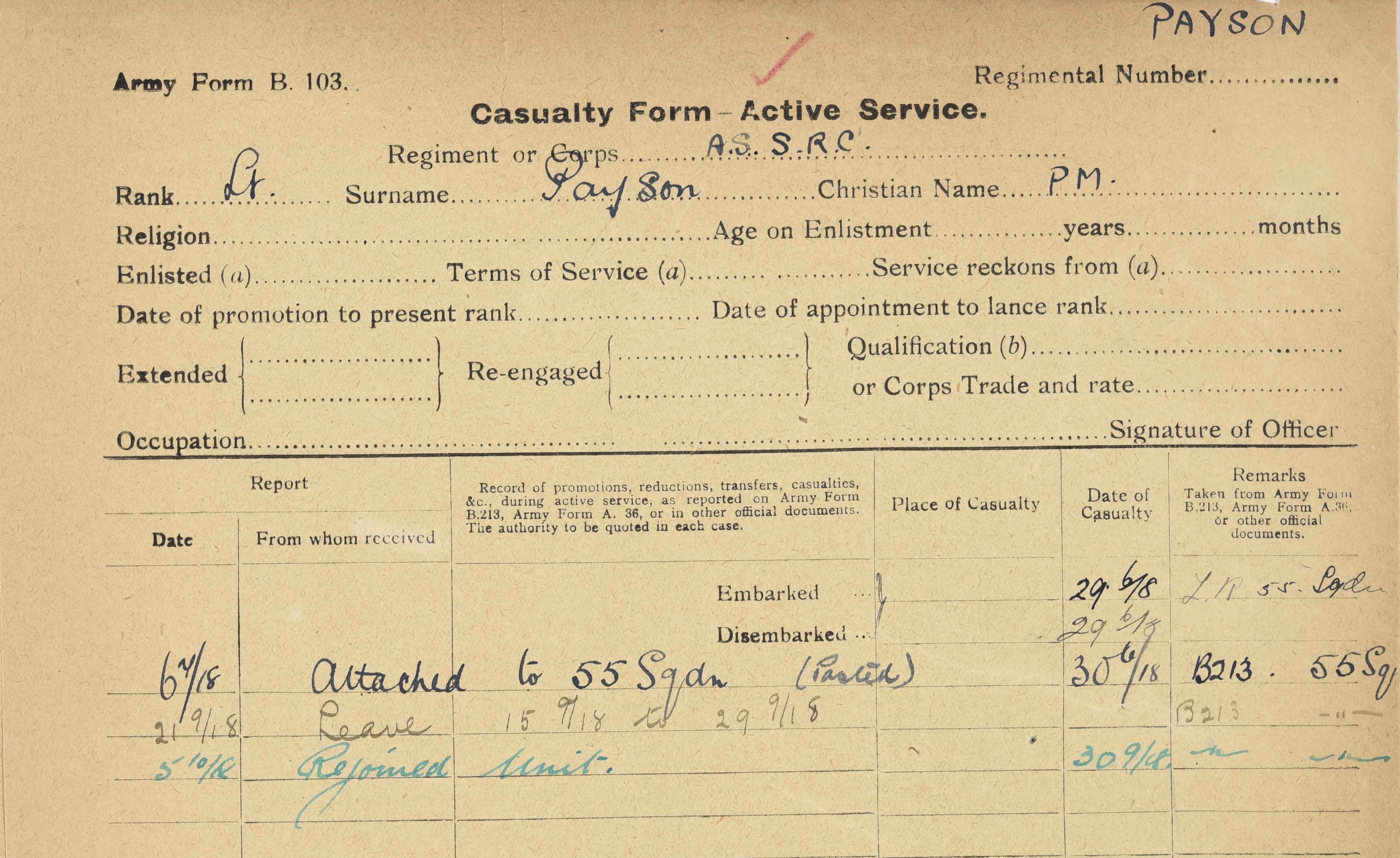

Payson’s R.A.F. service record notes, without providing a date, that he was at No. 6 Training Depot Station, one of the main training stations for day bomber pilots, located on Boscombe Down just outside of Amesbury in Wiltshire.20 It is likely that Payson went there at the end of January 1918, when many men from the second Oxford detachment were reassigned. Payson’s training at No. 6 T.D.S. probably paralleled that of Heater, who wrote of his time there that: “after seven hours of dual instruction I soloed with no difficulties on February 15, 1918. I flew from then on as often as a machine was idle, including slow, heavy, Armstrong-Whitworth early bombers, and B.E 2c’s, a lighter early bomber that was more fun to fly.”21 By early March 1918 Payson was ready to be recommeneded for his commission; in a cablegram dated March 13, 1918, Pershing forwarded the recommendation to Washington, and the confirmation came back dated March 19, 1918.22 He was still at Amesbury when he was placed on active duty on April 8, 1918.22a

On the preceding day, April 7, 1918, Edward Russell Moore, writing from Boscombe Down on April 7, 1918, recounted how “Four of my bunch, including myself, planned a 350-mile across country last Tuesday. Payson and I made the course, [George Clark] Sherman got lost in the clouds about half an hour from home on the start and [Robert Jenkins] Griffith got lost over Ipswich. The most distant point was Elmswell. It took us five hours and a half. Payson and I returned through a wind and rain storm, every twenty or thirty minutes we would strike rain or sleet. The machines tossed about like small boats at sea. I was sure glad to see the home field about 7:30 in the evening after three hours’ continuous flight.”23 A month later, Deetjen, now training at Stonehenge just to the northwest of Amesbury, noted in his diary “Saw old Pat Payson once more.”24

A post-war biography indicates that Payson trained at Turnberry,25 and this would again suggest that his training paralleled that of Heater, who was at the No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting and Gunnery at Turnberry, Scotland, from late May through the first part of June 1918. Payson may also, like Heater, have spent a brief period of time learning wireless telephony at Chattis Hill before serving as a ferry pilot—Payson’s laconic R.A.F. service record notes that he was assigned to the Independent Force B.E.F. from the “C.D.P.,” i.e., from the Central Despatch Pool, which oversaw the ferrying of planes to service units within England and from England to France.

According to his R.A.F. service record, Payson was assigned to the “Ind Force. BEF” as a DH.4 pilot on June 28, 1918. His casualty form shows him embarking for France the next day.26 The Independent Force (also called the Independent Air Force) had just recently come into existence. Though made up of R.A.F. squadrons, it operated independently of the other forces. Under the leadership of Hugh Trenchard the I.A.F. undertook bombing of aerodromes, railroad transport, and industrial centers inside Germany. Initially the I.A.F. consisted of three day-bombing squadrons, Nos. 55, 99, and 104, and two night-bombing, Nos. 100 and 216. Payson was posted to 55 on the last day of June 1918; he was one of seven second Oxford detachment men assigned to I.A.F. day-bombing squadrons around this time. Heater, Kenneth MacLean Cunningham and George Clark Sherman, were also assigned to No. 55, while Philip Dietz, Linn Daicy Merrill, and Horace Palmer Wells were assigned to No. 104; Dietz was soon transferred to No. 99.

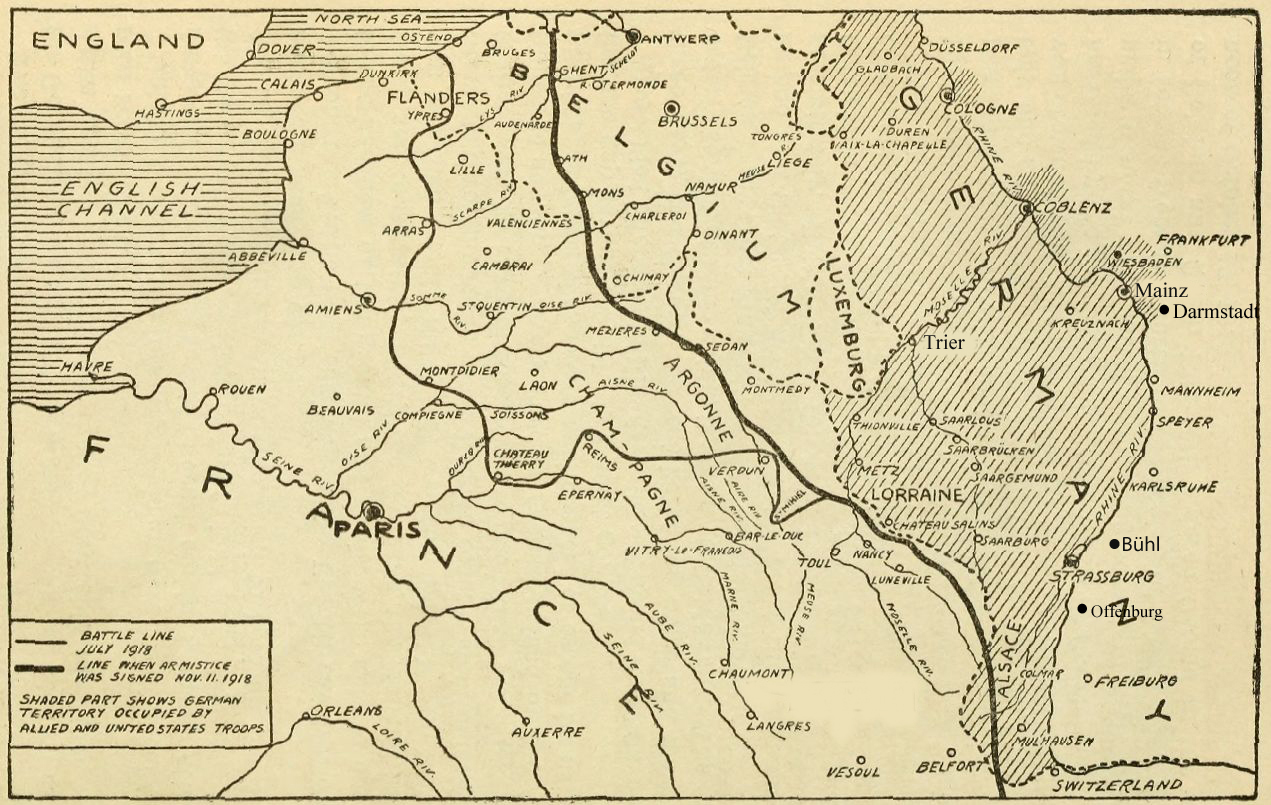

The day-bombing squadrons were stationed at Azelot in Lorraine, a few miles south of Nancy. Heater described the challenge faced by the seven second Oxford detachment members in getting there: “Nine months of training in England should have given the party of American pilots who left for the Independent Air Force on the last of June an idea of the sort of thing they were running into when they got to France, but most of them were unpleasantly surprised when they were bombed the first night in Boulogne, the second in Paris, the third while on their way to their squadrons in tenders, and several succeeding nights after reaching their stations.”27

Payson, Cunningham, and Wells were diagnosed with influenza soon after arriving in France. Payson was admitted to the 8th Canadian Stationary Hospital at Charmes, fifteen miles south of Azelot, on July 3, 1918, and discharged to No. 55 on July 7, 1918—just in time to experience a German raid on the aerodrome at Azelot that resulted in damage to structures but no casualties.28 While Heater and Sherman, after a fairly brief orientation period, began flying missions with No. 55 on July 16 and 17, 1918, respectively, Payson and Cunningham—perhaps slow to regain robust health after the ’flu—did not fly until the end of the month.29

On July 30, 1918, Payson flew his first mission. Both No. 99 Squadron, flying DH.9s, and No. 55, flying DH.4s, took off just after 5:00 in the morning, both intending to bomb the Mercedes aero engine works at Untertürkheim on the eastern outskirts of Stuttgart, 140 miles due east of Azelot. Each squadron set out, as customary for all three day-bombing squadrons, with twelve planes “in two formations of six machines each, the two formations acting as a protection for each other and keeping the Hun more or less at a loss as to the best method of attack.”30 As nearly always happened, adverse weather conditions encountered once the formations were in the air prompted a change of plan and the selection of a more manageable target. In this instance Frederick Williams, leader of Payson’s formation, determined that the squadron would target railway sidings at Offenburg, just a few miles east of the Rhine, well short of Stuttgart. Payson was almost certainly flying at the rear of the formation, the position generally assigned to new pilots—not, as Heater recalled, “that this position was any easier to fly than any other but it was less dangerous to the rest of the formation if the position was not flown correctly.”31 Heater also noted that new pilots usually flew planes new to them, further adding to the challenge. In Payson’s favor, however, on his first mission, was that his observer was experienced: Alexander Stewart Allan had been serving as a gunner and observer with 55 for at least four months, and probably longer. Since mid-July, Allan had been flying as Heater’s observer, but, exceptionally, Heater did not take part in the mission of July 30, 1918.

By the time the squadron neared Offenburg, flying at about 14,000 feet, each formation had lost one plane; it was the rule rather than the exception that a plane or planes had to drop out and return to the aerodrome, often because of engine trouble. The remaining ten planes apparently flew past Offenburg and then turned to approach their target from the east, at which point they encountered anti-aircraft fire. They dropped their bombs and were able to observe explosions. At 7:25, a little over two hours after leaving Azelot, they began the return flight. At this point they were attacked by five Albatross scouts which were soon joined by ten Fokker DVIIs. One DH.4 was badly damaged and two observers wounded, but all the planes and their crews arrived back otherwise safely at Azelot at 8:35. It is noteworthy that Payson, the new man flying a rear position, completed the mission without mishap.

The surviving planes of 99 Squadron had landed at Azelot fifteen minutes before those of 55. Thus Payson would have learned immediately on his return that Dietz, another new man flying a rear position, had not completed the mission. He had been, along with his observer, shot down and killed. Heater recalled that “now our trips against the Hun had more of a personal touch than they had before.”32

The next two missions flown by No. 55 Squadron were long ones, and Payson was assigned to take part in both. On July 31, 1918, twelve planes again set out in the early morning (5:20). This time Heater (with observer Allan), Sherman, and Cunningham were in the first formation. Payson, now with John Alfred Lee as his observer, was at the rear of the second formation. Once again two planes (including Cunningham’s) had to drop out, and once again weather conditions—wind and clouds—prompted a change of target. Cologne was abandoned in favor of Coblenz, where at 8:10 a.m., the DH.4s dropped “one 230lb, fourteen 112lb, sixteen 25lb and four 40lb phosphorous bombs”33; results could not be seen through the clouds. Returning home, the ten planes climbed to a bone-chilling 17,000 feet “to make it harder for any enemy aircraft trying to intercept them,”34 and, indeed, no enemy planes were sighted. The planes from No. 55 landed back at Azelot at 10:20, a grueling five hours after setting out.

Heater noted the different planes and engines used by the day-bombing squadrons: 99 and 104 flew DH.9s with B.H.P. 230 hp engines, while 55 had “Rolls Royce, 275 Horsepower D.H.4’s.” “The D.H.4 squadron was able to get a higher altitude and more speed, due to the more refined and higher powered motor, so it was natural that the longer work should fall on them.”35 Better engines alone, however, would not have accounted for the success of the five-hour mission in which Payson had just participated, given that the DH.4 normally had an endurance (flying time) of between three and four hours.36

55 Squadron had been pushing past this limit since at least early 1918. On March 9, 1918, they had bombed Mainz and on March 12, 1918, Coblenz: reaching the target in each case had required about two and a half hours flying time, and then two more hours from the target back to the aerodrome.37 These achievements are almost certainly accounted for by extra gas tanks fitted on the squadron’s DH.4s. These are mentioned by Leonard Miller in his discussion of developments in 55 Squadron in the spring of 1918, and Trenchard, after the war, noted that “No. 55 Squadron was equipped solely with short-distance machines, which had an air endurance of 3 1/4 hours only. But the squadron itself rectified this to the best of its ability by adding extra petrol tanks to the machines, which gave them an air endurance of 5 1/4 hours.”38 (I should note in passing that crews of 55 Squadron had oxygen equipment as well as electrically heated clothing available for their high altitude flying.39)

On August 1, 1918, No. 55 Squadron again attempted to bomb Cologne in an early morning raid. Rather than heading due north from Azelot to cross the lines at Nomeny as they had done the previous day, the two formations, with Payson and Cunningham in the first and Heater in the second, initially flew northwest from Azelot over St. Mihiel in order to cross the lines near Verdun. It was presumably not long after this that Payson, flying again with observer Lee, experienced engine trouble and turned back; he landed back at Azelot two and a half hours after taking off. He would later have learned that Cologne eluded his squadron mates once again; they settled for bombing Düren, a little over twenty miles southwest of Cologne. On their return some of the planes ran out of fuel and had to glide into Azelot after a little over five hours of flying time.

Bad weather meant that none of the I.A.F. squadrons flew missions for the next six days. On August 8, 1918, No. 55 Squadron successfully targeted factories at Rombas north of Metz; Heater, Cunningham, and Sherman flew in the first formation; Payson with his observer Lee was in the second. Although they passed through anti-aircraft fire and encountered enemy scouts, all the planes arrived safely back at Azelot. The next mission (not counting the frequent and important single-plane reconnaissance missions flown by 55) took place on August 11, 1918. It was on this mission that Cunningham, flying in the first formation, provided cover for formation leader John Ross Bell, who had to return when his petrol tank was hit and began to leak badly. Heater, with observer Allan, and Payson, with observer Lee, were in the second formation, which was broken up in the encounter with enemy aircraft and returned to Azelot without reaching the target or dropping their bombs.40 The records available to me do not show whether Payson took part in that day’s second raid, which, after three planes returned with engine trouble, was in any case abandoned.41

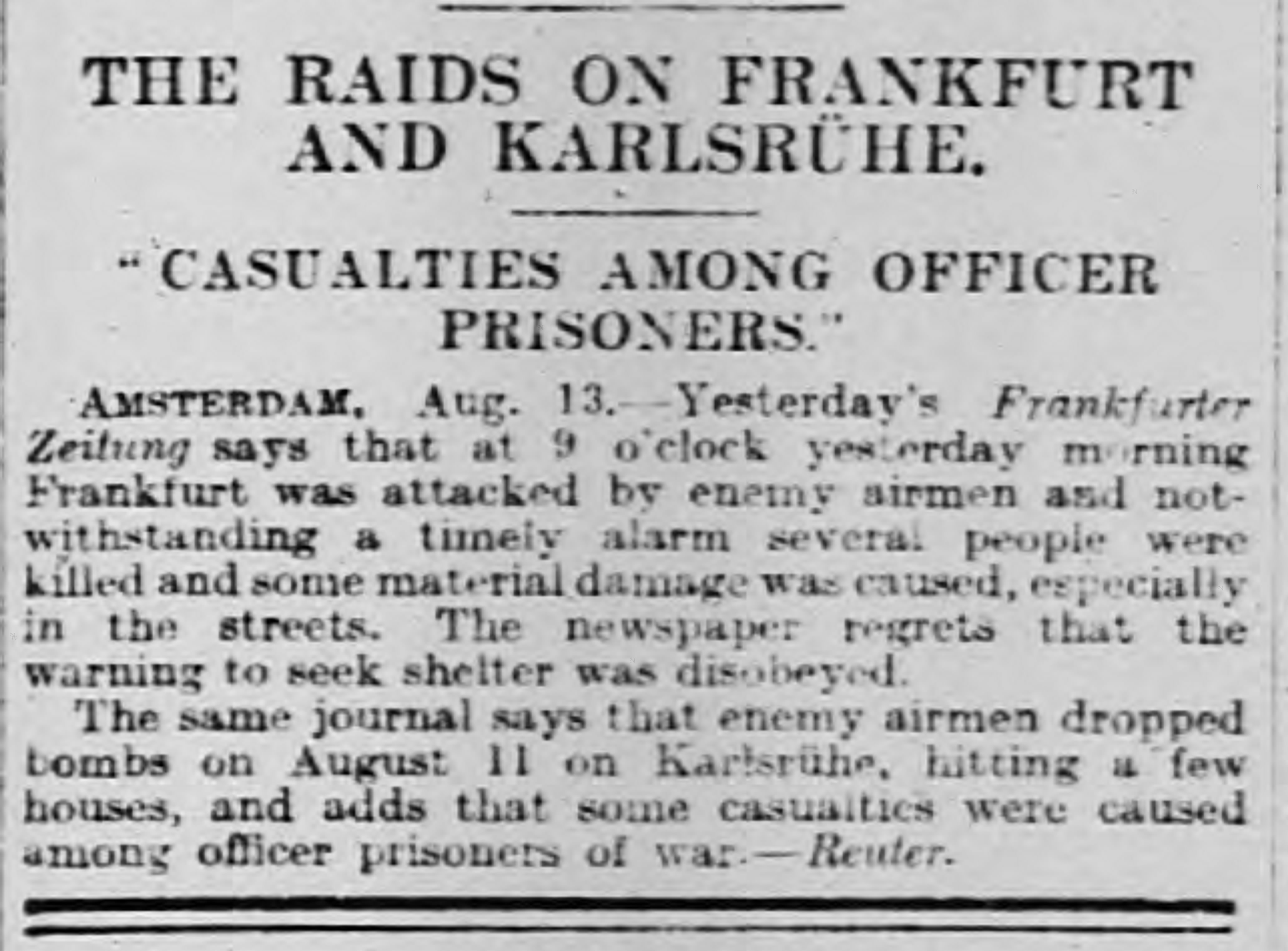

Payson did participate the next day, August 12, 1918, in what the Official History labeled the “superb raid on Frankfurt.”42 Heater, in a letter home a few days later, described this raid as “the worst time we’ve had since I’ve been here and from what others say it’s the worst the squadron has ever had.”43 Heater with observer Allan in DH.4 D8396 and Payson with observer Lee in A7783 flew in the second formation; the planes left Azelot at 5:20. 44 By the time the twelve planes of 55 were north of Mannheim, they were being shadowed and attacked by about forty enemy aircraft, “but they did not press the attack with much vigor owing to the excellent formation of the D.H.4s’s”45 and the work of 55’s observer/gunners—one of whom, Earle Richard Stewart, was the single casualty of this raid. “The pre-occupation provided by the fighting did not affect the bombing. Before leaving Frankfurt on which more than a ton of bombs was dropped, bursts were seen on the town east of the goods station and eight [photographic] plates were exposed to record them.”46 Enemy planes were again encountered on the return flight. All the planes of No. 55 Squadron reached Azelot, “though they only just cleared the trenches on their return journey, running completely out of petrol” after five and a half hours of flying.47 According to the raid report of the leader of this mission, Benjamin James Silly, “One enemy machine was shot down in flames and seen to break up, another seen to crash into a wood, two others were driven down out of control, and one was driven down.”48 In one official source, Payson is given credit for one of the downed planes.49

Payson with observer Lee continued to participate in every bombing mission flown by No. 55 through the end of August. On August 13, 1918, they were in DH.4 A7586; the initial target was again Frankfurt, but because of clouds, they bombed the German aerodrome at Bühl twenty miles northeast of Strasbourg instead. The next day Payson and Lee were in A7781 when the squadron, hoping for Cologne, instead bombed railway sidings at Offenburg, about twelve miles southeast of Strasbourg.

On August 16, 1918, Payson and Lee were in one of the eleven planes, rather than the customary twelve, that set out at 5:20 a.m., heading due east towards Strasbourg and the Rhine, and thence north to Mannheim and Darmstadt.50 Heater recalled that “Payson had a machine with a new motor, one that had never been over the lines and it started going dud on him just as we hit the Rhine, about fifty or sixty miles the other side of our lines. When he saw it was impossible to make it with the formation, he started for home, not however, until he had tried to make another machine, a new man who was hopelessly behind go back with him, and all the way he lost height. He made our side of the lines though, but only by sheer luck, for several Huns came for him, but lacked the nerve to come in close and shoot him down, for he was being Archied all the time and the Hun pursuit does not like it’s [sic] own Archie. The man whom Payson tried to turn back was shot down over the objective, as were two others later in the same show.”51 The unfortunate pilot whom Payson tried to help was almost certainly Ernest Albert Brownhill, who had been posted to No. 55 Squadron on July 31, 1918, and was flying last in the second formation on this, his first and only mission.52 His observer, also on his first mission and also killed, was William Thomas Madge, posted to No. 55 Squadron just ten days previously.53

On 55’s next mission, on August 22, 1918, after a period of unfavorable weather, the initial target of the twelve planes setting off at 5:30 a.m. was again Cologne. This time it was Heater with observer Allan who, along with three other teams, had to turn back. Two formations of four planes each, with Payson and observer Lee in the first, reached Trier; strong wind prompted leader Bell at this point to switch to the closer target of Coblenz, which the eight planes bombed shortly after 8:00; they arrived back at Azelot at 10:20, nearly five hours after setting out.

Payson with observer Lee and Heater with Allan were in the first formation taking off the next day at 10:15. Cologne was again the intended target, but it was again abandoned in favor of Coblenz because of heavy clouds, which then also made that target unfeasible. Ten planes—two from the first formation having returned early due to engine trouble—dropped their bombs on the railway station at Trier, and arrived safely back at Azelot at about 2:30 p.m. This was Heater’s last flight with 55, but a vivid account of the squadron’s next mission two days later evidently reached him: the last days of August were grim ones for the squadron.

On August 25, 1918, the two formations of No. 55 Squadron again got off to a late start, at 11:40, again with the intention of bombing Cologne or, as dictated by the weather, Coblenz. Payson and Lee were in DH.4 A2131 in the first formation, led by Bell. Because three of the planes in the second formation, including that of the leader, had engine trouble, they, exceptionally, failed to rendezvous with the first formation, which nevertheless pressed on, crossing the lines at Nomeny. Strong winds encountered over Trier made it imprudent to try for Coblenz, much less Cologne, and Bell led his formation southwest to Luxembourg, where they dropped their bombs.54 Just as they started back towards the lines to the west, they were attacked, fiercely. Observer Allan, flying with James Balfour Dunn, was wounded. Heater recounted how “Payson’s observer [Lee] was killed, his machine completely riddled, two of his controls shot away, several instruments on the instrument board were shot off, and five bullets when through the small pad on which he was sitting. . . . Lieutenant Payson succeeded in getting to a new position in the formation and reaching home.”55 Keith Rennles in his Independent Force gives more detail about “getting to a new position”: “Lt. Payson, now without an observer, slid his machine underneath that of Lt. [Donald Jayne] Waterous using his observer, 2Lt [Cyril Lancelot] Rayment to keep the enemy aircraft off his back. The fight continued towards the lines which were crossed at Verdun at 13,000ft.”56 Heater understood that “Four machines of the formation were shot down,” but he was perhaps conflating the events of this mission with those of August 30, 1918, for, on August 25, 1918, “All six machines made it back to Azelot with some badly shot about.”57 Lee was dead, and Allan, with whom Heater had flown many times and with whom Payson flew his first mission, died of his wounds two days later.

Weather prevented flying on August 26, 1918, and continued poor the following morning. In the afternoon, however, a mission was undertaken with the intended target of Bettembourg— reconnaissance indicated that train movements there had not been disrupted.58 Two planes from the second mission had engine trouble, but the other four, as well as the six planes of the first formation, in which Payson was flying with observer Charles Wilfred Clutsom, crossed the lines at Verdun.59 Extensive cloud cover prompted leader Evans Alexander McKay to decide the squadron should drop their bombs at Conflans-en-Jarnisy, due east of Verdun and well south of Bettembourg. Despite heavy anti-aircraft fire, all the planes returned safely to Azelot.

I.A.F. squadrons flew no missions on August 28 and 29, 1918, the weather being unfavorable. Curiously, the second of two victory credits accorded to Payson while he was with the I.A.F. is dated August 28, 1918.60

Despite continuing clouds and wind on August 30, 1918, both 99 and 55 set off on missions around 8:30 in the morning. 55 was once again tasked with bombing Cologne, but from the outset it was clear that this was wildly optimistic. Weather was not the only problem. “The raid was unfortunate from the start as the second formation under Lieutenant Ernest John Whyte was unable to keep up with the first formation, led by Captain J. R. Bell.”61 Payson was flying with observer Clutsom in this second formation of six planes, which, while Bell’s formation headed north from Nomeny, crossed the lines at Fresnes-en-Woëvre twelve miles east-southeast of Verdun and continued east-northeast to Conflans-en-Jarnisy, where they dropped their bombs. They were then attacked by eight Pfalz scouts, which shot down one plane (D8396) and mortally wounded an observer. Four planes from this formation, including Payson’s, returned to Azelot shortly after noon; the fifth plane, piloted by Edward Wood with his dying observer, Charles Evans Thorp, landed at Pont-Saint-Vincent, a few miles west of Azelot.

The first formation fared even worse. After dropping bombs on Thionville, they were attacked by Pfalz scouts and Fokker DVIIs. Only leader Bell with his observer Rayment made it back to Azelot. One plane was able to put down at Pont-Saint-Vincent, but the others had made forced landings or crashed in enemy territory. In total, 55 lost eleven men—killed or prisoners—on this raid. That evening “the Hun made his first really serious bomb raid on the Squadron’s living quarters, coming over about nine in the evening and catching everybody unawares.”62 No one from 55 was hurt, but the atmosphere must have been well beyond bleak that night.

No. 55 Squadron next flew bombing missions on September 2, 1918. In coordination with Nos. 99 and 104 Squadrons, they attacked the German aerodrome at Bühl in the morning and again in the afternoon. Payson is not recorded as having taken part in either of these, although incomplete records leave open the possibility that he was assigned to fly them but returned early with engine trouble.63

Payson took part in 55’s next mission, on September 4, 1918, which also targeted Bühl once it was determined that the wind was too strong to make reaching Karlsruhe feasible. Payson, now with observer George Frederick William Adams, was in the middle of the second formation. Both formations this day began with only five planes, perhaps necessitated by the recent heavy casualties. One plane had to return before the target was reached; the remaining nine planes dropped their bombs on the aerodrome and returned without incident.

Bad weather precluded missions on September 5 and 6, 1918. When flying resumed on September 7, 1918, Payson, again with Adams, flew his sixteenth and last mission with No. 55.64 Unusually, only one formation of six planes set out, despite what had happened to single formations at the end of August. The ambitious target was once again Cologne, but was changed en route to the railway at Ehrang just north of Trier. Having dropped their bombs from an altitude of 16,500 feet, the planes climbed to 17,5000 on their return before descending and arriving safely back at Azelot.

It was planned that the I.A.F. would assist in the run-up to the St. Mihiel Offensive by bombing selected railways and aerodromes, but the abysmal weather put paid to flying until two days after the offensive had begun.65 Although still with the squadron, Payson did not fly on September 14, 1918, when two formations from No. 55 Squadron again targeted Ehrang—perhaps because his two-week leave began the next day. The day after the leave was over, on September 30, 1918, he “rejoined unit,” which is to say, he left the I.A.F. for the American Air Service.

On October 4, 1918, Payson, along with Merrill from No. 104 Squadron I.A.F., reported to the U.S. 166th Aero Squadron at Maulan, about forty-five miles west of Azelot.66 Second Oxford detachment members Paul Vincent Carpenter, John Joseph Devery, Harrison Barbour Irwin, Stoughton, and Albert Elston Weaver had already been assigned to the squadron; Fremont Cutler Foss would join them on October 9, 1918.

The 166th had been added to the American 1st Day Bombardment Group on September 25, 1918, the day before the opening of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The other three squadrons in the group (the 11th, now led by Heater, the 20th, and the 96th) participated in the offensive from the beginning, but the 166th needed time to settle in and to do practice sorties in their “Liberty DH-4s,” i.e., DH.4s with American Liberty engines, before actually taking part in raids—particularly given that Payson and Merrill were apparently the only pilots in the squadron, other than the commanding officer, Victor Parks, Jr., with combat flying experience.

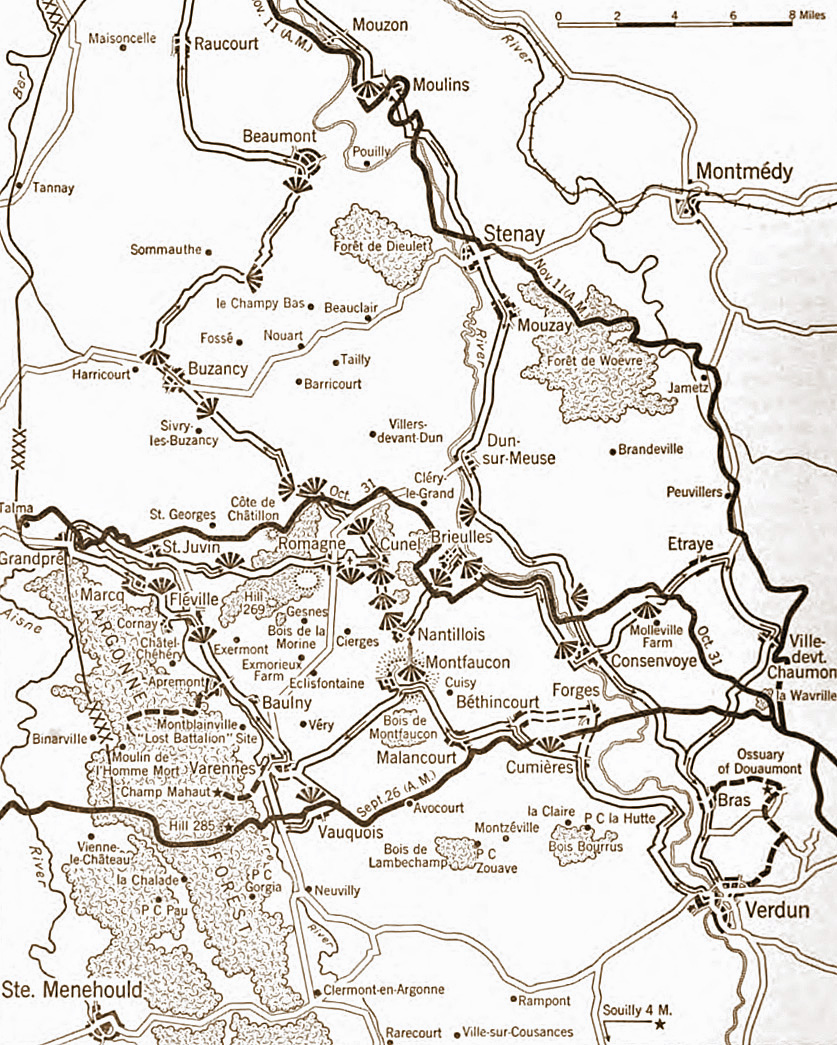

The 1st Day Bombardment Group squadrons flew relatively few missions in the first part of October, at least in part because of bad weather, and it was not until October 18, 1918, that the planes of the 166th Aero participated in a mission, a raid to bomb Buzancy, an important German defensive position in the Ardennes north of the slowly advancing American front lines.

The entry for the October 18, 1918, mission in Howard Rath’s “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” lists ten pilot / observer teams of the 166th on this raid; the list does not include Payson.67 According to the narrative “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron” by Charles C. Hicks, however, thirteen planes, rather than ten, from the 166th took off at 14:10 on this raid. Hicks’s narrative goes on to recount how “The formation was attacked by a formation of eight Fokkers and in the course of the combat two of our planes were crippled one with a bullet through the gasoline tank, the other with a disabled engine. Both landed behind our own lines.”68 Payson, with an unknown observer, was almost certainly flying the plane that was shot through the gas tank. In later recommending Payson for a D.S.C., C.O. Parks describes Payson’s actions on what appears to have been this raid, without providing a date: “On one raid over the lines with this Squadron, his plane was attacked in force by the enemy, and he fought them until far back of our own lines. Lieut. Payson skilfully [sic] manoeuvred his ship and evaded the German planes, . . . and with his Observer fought off five enemy planes, who seemed determined to bring him down. He landed near Révigny and his ship was salvaged, having been literally shot to pieces. The landing wires were shot away, the planes riddled, and his gas tank shot through.”69 Eleven years later, Payson was awarded a silver star citation, and the language of the award clearly draws on Parks’s wording, while also providing a date: “For gallantry in action near Buzancy, France, Oct. 18, 1918.”70

Payson with observer George Deady Melican was among the fourteen pilots assigned to take part in the squadron’s next mission on October 22, 1918.71 That day, however, “All planes returned before reaching ovjective [sic] on account of rain and very dense clouds near the lines.”72

Payson, now with observer Richard Smith Austin, flew the next afternoon’s mission, and every subsequent mission undertaken by the squadron. During the St. Mihiel Offensive in September 1918 the squadrons of the 1st Day Bombardment Group had learned to their cost (as had No. 55 Squadron in late August) that small formations were exceedingly vulnerable. Thus the mission on October 23, 1918, which was made up of four formations—twelve planes from the 96th Aero, ten from the 20th, thirteen from the 11th, and thirteen from the 166th—was standard; there are also occasional mentions of scout formations providing protection. On October 23, 1918, the forty-eight planes set off in the early afternoon to bomb the Bois-de-Barricourt and the Bois-de-la-Folie, just south and east of Buzancy, presumably part of the effort to clear the way for the advance of the American forces now a few miles to the south. According to the squadron history, six planes from the 166th led by Merrill reached the Bois-de-Barricourt and dropped their bombs, with “results unobserved on account of combat.”73 Whether Payson’s was among the planes that reached the objective cannot be determined from the documents available to me.

After three days of inclement weather, another four-squadron mission was flown the afternoon of October 27, 1918; the target this day was Briquenay, a few miles to the west of the target of the previous mission. An operations report for this raid indicates that Payson in DH-4 32871 with his observer Austin was among six (out of fifteen) pilots from the 166th who were unable to reach the objective; no reason is given, but engine trouble seems a likely culprit.74

After another day of bad weather, the 166th flew two missions on October 29, 1918. Payson took part in both of them. On the first one, which set out at 8:10 and returned two hours later, the 166th initially flew with planes from the 11th Aero, all of which, however had to drop out before reaching the objective as did five of the from the 166th. Payson and Austin, again in 32871, were among the eight teams that succeeded in reaching Montigny-devant-Sassey; they dropped their bombs and observed bursts on railroad yards and ammunition dumps just before 9:30. Although they saw enemy aircraft, they were, fortunately, not attacked; a note in the operations report indicates that “20 planes from the pursuit protected formation.”75

All four squadrons took part in the afternoon raid. Many planes had to drop out, but Payson and Austin in 32871 were among those who reached and bombed Damvillers, somewhat farther south and east of their previous objectives.

The next day, October 30, 1918, Payson in 32871 with observer Austin flew both the morning mission to Bayonville and the afternoon mission to bomb Belleville, reaching the objective both times. An operations report notes apropos the 166th that “8 EA Fokkers, Albatross and Siemen Schuckert attacked formation near Belleville 15:32,” but does not record the squadron’s response.76 Even without the enemy planes, Payson had a close call on the afternoon raid: the History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A. recounts how he “narrowly escaped being hit by one of our bombs as he flew under our formation just as the objective was reached.”77

Aggressive enemy aircraft were encountered again during the mission targeting Tailly the next day, the last day of October: “9 EA Fokkers D 5 attacked formation before reaching objective and continued attack back to the lines.”78 According to the squadron history, “two of our planes were crippled, one with a bullet through the gasoline tank, the other with a damaged engine. Both planes landed inside our own lines.”79 One of these planes was DH-4 32569, flown by Sam Pickard with observer Stanley Lockwood Cochrane; Cochrane was killed and Pickard wounded. It is likely that the other damaged plane was 32871 flown by Payson and Austin, as the next time Payson flew, he had a different plane; 32871 disappears from lists of teams and planes in the operations reports of the 166th Aero and of the 1st Day Bombardment Group.80

After two days of bad weather, the 166th flew its final four missions on November 3, 4, and 5, 1918, with the objective each day a bit farther north, reflecting the progress of the American advance in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Payson and Austin flew both raids on November 3, 1918; these were again missions made up of planes from all four 1st Day Bombardment Group squadrons. Two planes from the 166th, including Payson’s DH-4 32467, failed to reach the objective, Stenay, in the morning, but succeeded in bombing Beaumont in the afternoon. The objective the next afternoon, November 4, 1918, was Montmédy; Payson and observer Austin were able to reach the target. Fair weather this day made it possible to observe the results of the bombing but presumably also encouraged enemy aircraft to attack; it was on this four-squadron mission that two planes from the 11th Aero, including that flown by second Oxford detachment member Dana Edmund Coates, were shot down. The 166th shot down three enemy aircraft that day, one of these being shared among several pilot and observer teams, including Payson and Austin.81

On November 5, 1918, the 11th, 20th, and 166th Aero Squadrons flew their final raid. The 96th, for whatever reason, did not participate, and all of the planes of the 11th had to turn back before crossing the lines. While seven of the eleven planes from the 166th reached and bombed Raucourt-et-Flaba, four, including 32467 flown by Payson (on his thirteenth and final mission with the 166th) and Austin, did not. Unfavorable weather kept planes on the ground through November 11, 1918.

Parks’s recommendation dated November 12, 1918, that Payson be awarded the D.S.C. includes the information that he was now a Flight Commander. And Payson’s promotion, presumably to captain, was approved by the Air Service, but a letter dated November 26, 1918, from the Chief of Air Service, Mason Mathews Patrick, “expressed regret that instructions from the War Dept. had discontinued all promotions after Nov.11.”82

Payson remained with the 166th Aero for about four more months. Soon after the armistice, the squadron was reassigned to the Third Army (the Army of Occupation) and was stationed initially at Joppécourt and then relocated early in the new year to Trier. Payson was now seeing from the ground places he had targeted from the air while he was with No. 55 Squadron. Early in March 1919 Payson must have started making his way from Germany to the west coast of France; for on March 16, 1919, he sailed from Brest on the U.S.S. George Washington, arriving at Hoboken on March 25, 1919. Payson returned to Maine and the Payson family investment bank.

mrsmcq January 11, 2022

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Payson’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., Veterans Administration Master Index, 1917-1940, record for Phillips Merrill Payson. For his place and date of death, see Ancestry.com, Maine, U.S., Death Index, 1960-1997, record for Phillips M Payson. The photo is the one used on p. 81 of Ticknor’s New England Aviators 1914–1918, vol. 2.

2 On the marriage of Samuel Payson and Mary Phillips, see Anderson, The Great Migration: Immigrants to New England, 1634-1635, v. 5, p. 394. Jackson, A History of the Early Settlement of Newton, published in 1854, states, p. 452, that Samuel Payson married Mary, daughter of Thomas Wiswall. A few years later, Savage, A Genealogical Dictionary of the First Settlers of New England, p. 373, repeated this, while, p. 374, expressing doubts. The page for Phillips Payson, son of Samuel and Mary, at Wikipedia has unfortunately followed Savage’s p. 373 claim; see Wikipedia, “Phillips Payson.”

3 On the Payson family, see, in addition to the sources cited above, Winters, Memorials of the Pilgrim Fathers, pp. 60–63, as well as documents available at Ancestry.com.

4 The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, vol. 26, p. 163.

5 “1913 Eleven Fails in Crucial Games,” p. 2.

6 Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Phillips Merrill Payson. See also Ticknor, New England Aviators, vol. 2, p. 79.

7 See Payson’s draft registration, cited above.

8 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

9 Winslow, RFC/RAF No. 56 Squadron Diary of Paul Winslow. 1917-1918, p. 39.

10 Deetjen, diary entry for October 9, 1917.

11 Deetjen, diary entry for October 23, 1917.

12 Deetjen, diary entry for October 21, 1917.

13 Deetjen, diary entry for November 1, 1917.

14 Milnor, photo album.

15 Chalaire, “Thanksgiving Day with the Aviators Abroad.”

16 “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers. On 36, see See Philpott, Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 402, and Wikipedia, “RAF Usworth.”

17 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 259.

18 Castle’s remark is reported by Foss, in a diary entry for January 12, 1918.

19 Deetjen, diary entry for December 27, 1917.

20 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Phillips Morrell [sic] Payson.

21 Quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 260.

22 Cablegrams 726-S and 1008-R.

22a Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

23 “Letters from Soldiers” (May 23, 1918).

24 Deetjen, diary entry for May 11, 1918.

25 Ticknor, New England Aviators 1914–1918, vol. 2, p. 79.

26 “Lieut. P M Payson AS SRC.”

27 Heater, [Informal account], p. 124.

28 On his hospitalization, see Payson’s R.AF. service record, cited above. On the bombing of Azelot, see Miller, The Chronicles of 55 Squadron, R.F.C. and R.A.F., p. 74.

29 Accounts of the missions flown with No. 55 here and in what follows, unless otherwise noted, are based on Rennles, Independent Force.

30 Heater, [Informal account], p. 126.

31 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 118.

32 Heater, [Informal account], p. 126.

33 Rennles, Independent Force, p. 31.

34 Ibid.

35 Heater, [Informal account], p. 125.

36 Herris and Pearson, Aircraft of World War I: 1914–1918, pp. 65 and 146; Mason, The British Bomber since 1914, p. 68; Bruce, The de Havilland D.H.4, p. 11; Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File, p. 17.

37 Neate, “The Diaries of Captain Orlando Lennox Beater,” p. 72–73; The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924, pp. 21, 22.

38 Miller, The Chronicles of 55 Squadron, R.F.C. and R.A.F., p. 65; Trenchard, [Report on the work of the Independent Air Force], p. 134. 55 Squadron’s efforts to extend the endurance of the DH.4 can be traced back to the preceding autumn. Beater (see Neate, cited above), in his diary entry for November 23, 1917, records the arrival of “a new machine. . . . It has a 375hp engine, sufficient petrol for a nine or ten hour trip . . . .” A few days later, however, after a forced landing by [Alexander?] Gray, it was “practically a ‘write-off’” (Beater diary entry for November 30, 1917). I am grateful to Andrew Pentland for identifying this remarkable plane as DH.4 A7763 and for copies of the relevant R.F.C. aircraft documents. The engine in A7763 was an early Eagle VIII, and it was outfitted with “special tanks.” See the entry for A7763 at Pentland, Royal Flying Corps.

39 See Miller, The Chronicles of 55 Squadron, R.F.C. and R.A.F., pp. 29–30; and see Beater’s diary entry for February 12, 1918 (Neate, “The Diaries of Captain Orlando Lennox Beater,” p. 69).

40 The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924, p. 41, indicates that the original target for this raid was Mannheim; Rennles, Independent Force, p. 81, indicates Frankfurt.

41 The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924, p. 41.

42 Ibid, p. 42.

43 Heater, Letter of August 15, 1918 to Mr. and Mrs. J. R. Heater.

44 Rennles, Independent Force, provides plane numbers when available; the original records are evidently incomplete. There is a photo of A7783 on p. 39 of Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File, taken after a bad landing at Waddington; repaired, it had been allotted to 55 Squadron at the end of July 1918.

45 The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924, p. 42.

46 Ibid.

47 Trenchard, [Report on the work of the Independent Air Force], p. 137.

48 Miller, The Chronicles of 55 Squadron, R.F.C. and R.A.F., p. 103.

49 “Confirmed Victories U.S. Air Service Officers with Independent Air Force.” See also “American Fliers with the I.A.F.,” p. 134A.

50 Rennles, Independent Force, p. 91, indicates that the planned target for this raid was Cologne; The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924, p. 44, indicates that “The objective laid down in orders was the distant target at Darmstadt. . . .”

51 Heater, [Informal account[], pp. 129–30,

52 “2nd Lieut. Ernest Albert Brownlee [sic] RAF.”

53 “2nd Lieut. William Thomas Madge RAF.”

54 It is unclear whether by “Luxembourg,” Rennles, Independent Force, p. 103, and The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924, p. 45, mean the country or the city. There are sources that indicate that both the capitol and Bettembourg were bombed this day, and it appears that only 55 could have been responsible for this. See the IAF communiqué excerpted at “100 years ago today – 25 August 1918”; see also this date at the interactive map at The Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C²DH), Éischte Weltkrich.

55 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 121.

56 Rennles, Independent Force, p. 103.

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid., p. 105.

59 Clutsom’s last name is variously given on official and unofficial documents as Clutsom and Clutson, and I have not been able to find clear documentation of how he himself spelled it.

60 “Confirmed Victories U.S. Air Service Officers with Independent Air Force.”

61 The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924, p. 46.

62 Miller, Chronicles of 55 Squadron R.F.C. and R.A.F., p. 80.

63 See Rennles, Independent Force, pp. 111 and 112.

64 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 121, credits Payson with fourteen missions with 55; this is the number also given in a letter from the Air Ministry cited on p. 80 of Ticknor, New England Aviators 1914–1918, vol. 2.

65 The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924, p. 48.

66 See the roster on p. 87 of Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron.”

67 Rath, op. cit., p. 130. The list is identical to that signed by Devery on p. 90 of Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron”—which may simply mean that one inaccurate list was copied into another source.

68 Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron,” p. 85.

69 Cited in Ticknor, New England Aviators 1914–1918, vol. 2, pp. 79–80.

70 “Three Get Awards for War Exploits.”

71 Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron,” p. 91.

72 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 131.

73 Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron,” p. 85; quotation from Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 133. The 166th’s raid report indicates that “7 reached objective” (Hicks, “History…,” p. 104).

74 The 166th’s raid report (Hicks, “History…,” p. 105) indicates, without providing plane numbers, that eleven of the fifteen planes reached the objective. Here and elsewhere there are discrepancies among the reports provided by the documents. I have in the main followed the more detailed reports in Rath’s “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations.” On Rath and the writing of this document, see now Rath and Harrington, First to Bomb, pp. 121–23.

75 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 138.

76 Ibid., p. 140.

77 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 171.

78 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 142.

79 Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron,” p. 85.

80 It is possible—given some coincidence in details (shot through gas tank; damaged plane) that it was for this day’s work that Parks recommended Payson for the D.S.C. and that the later silver star citation made an error in providing the date of October 18, 1918. On balance, however, I believe the silver star citation date is the correct one.

81 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 149, records “1 E.A. went down in flames, another crashed, and one went down out of control. (166th).” For the official credits, see Sherman, Operations of Air Service, First Army from August 10th to November 11th, 1918, p. 102; also Victories and Casualties, p. 38.

82 Cited in Ticknor, New England Aviators 1914–1918, vol. 2, p. 79.