(Pea Ridge, Arkansas, March 13, 1896 – Kelly Field, Texas, February 1, 1920)1

Northolt, Croyden, Turnberry & Ayr ✯ Ferry pilot work ✯ No. 65 Squadron R.A.F. ✯ The 148th Aero at Dunkirk ✯ The 148th at Allonville ✯ The Cambrai Push ✯ The American Front and post-armistice

John Kindley, one of Field Eugene Kindley’s ancestors, emigrated from Europe (perhaps Scotland, but probably Germany) before the Revolutionary War to what is now North Carolina.2 One of his descendants, Kindley’s grandfather, moved from North Carolina to northwest Arkansas just before the Civil War. Kindley’s father, George Cephus Kindley, was born in Missouri, where the family briefly took refuge during the conflict.3 Kindley’s mother, Frances Ella Kindley, née Spraker, was the daughter of William Spraker, a fifth-generation New Yorker, who also had moved to Arkansas around the time of the Civil War.4

Kindley’s parents were both teachers and lived and taught for a time in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma).5 His mother died when Kindley was two years old.6 Not long afterwards, in early 1902, Kindley’s father sailed for the Philippines as one of the many U.S. government teachers dispatched to the newly acquired territory, leaving Kindley, an only child, in the care of his Arkansas relatives.7 In 1903 Kindley, accompanied by an acquaintance of his parents from their Oklahoma days, travelled to the Philippines to join his father, returning, apparently on his own, to Arkansas in the spring of 1908.8 He spent the next five years in Gravette, Arkansas, living with his father’s brother and his family, including Uther Kindley, a cousin to whom he became particularly close.9 Kindley attended high school in Gravette and worked a variety of jobs; he did not attend college.10 In 1916 he became a co-owner, with James C. Perry, of a movie theater in Coffeyville, Kansas, about eighty miles northeast of Gravette. The move had perhaps been facilitated by the presence there of another cousin (technically a second cousin), Edward Ellsworth Kindley.11

In early May 1917, less than a month after the U.S. entered the war, Kindley determined to try for a commission in the army and applied for the officers training corps at Fort Riley, Kansas. He was accepted for the infantry.12 Towards the end of June, an opportunity arose to volunteer for the Signal Corps and aviation, and he jumped at it.13

It has sometimes been assumed that college attendance was required of aviation candidates. In 1919 an ill-informed congressman would inquire of WWI ace Field Kindley whether he was “familiar with that requirement that the War Department evidently had prohibiting any man but a college graduate from entering the Aviation Service as a flyer.”14 But already the 1916 Signal Corps requirements left some wiggle room by stipulating that candidates for the Aviation Section have “the equivalent of a college education.”15 When, in 1917, the age requirement was lowered from 21 to 19, regulations noted the desirability of some college work, but required only high school graduation.16 When Kindley filled out his application for the Aviation Section, Signal Officers Reserve Corps in mid-July 1917, his five years of business experience was accepted as “the equivalent of two years’ college education.”17 It is nonetheless true that Kindley would be in a minority, as most of his American fellow pilots would, indeed, have been to college.

His application accepted, Kindley left for ground school at the University of Illinois in mid-July 1917.18 He graduated September 1, 1917.19 Then, along with most of the men from his ground school class of about thirty, he chose or was chosen to go to Italy for flying training and thus sailed with the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” to England. They departed New York on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania, which made a brief stopover at Halifax before joining a convoy. During the voyage across the Atlantic, there was leisure time, but the men also took Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, who sailed with them, and, once they entered dangerous waters, took turns at submarine watch.20 When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men learned that they were not to go to Italy, but to stay in England. They travelled by train to Oxford where they spent the month of October repeating ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics.

On November 3, 1917, most of the detachment, including Kindley, went to Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend gunnery school at Harrowby Camp and to wait for places at training squadrons. Kindley would later remark that “We had a very thorough machine-gun course in the United States. We had a thorough machine-gun course at Oxford, and then took another machine-gun course at Grantham.”21

While at Grantham, Kindley’s moustache was the object of cadet high jinks. Grider wrote in his diary shortly after their arrival that “[Uel Thomas] McCurry came in our hut tonight and begged me with tears in his eyes to go with him to cut Kindley’s mustasche [sic] off,” and a week later that “We caught Kindley last night and cut off his mustasche.”21a For whatever reason, there was enmity between the two Arkansans, and another diary entry suggests that when the two of them were among a group of fifty cadets at Grantham assigned to training squadrons in mid-November, Grider ensured that Kindley was not assigned with him to Thetford: “I had Kindley in my crew tonight and swapped him off for [Marvin Kent] Curtiss [sic]. [Clarence Horn] Fry said it was like trading horses. I would have given boot to be rid of Kindley.”21b

Northolt, Croyden, Turnberry and Ayr

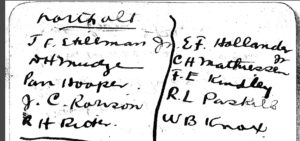

Perhaps well away from the rather boisterous group going to Thetford, Kindley set out with nine others on November 9, 1917, for Northolt, on the northwest outskirts of London.22 Another of the men assigned to Northolt, Parr Hooper, reported that “Everybody here are officers except the mechanics. There are about 150 men training, 2 elementary squadrons and one advanced. We 10 Americans (5 in the 2nd squadron and 5 in the 4th squadron) are ranked as cadets but are treated as officers.”23 Kindley was assigned to No. 4 Training Squadron.24

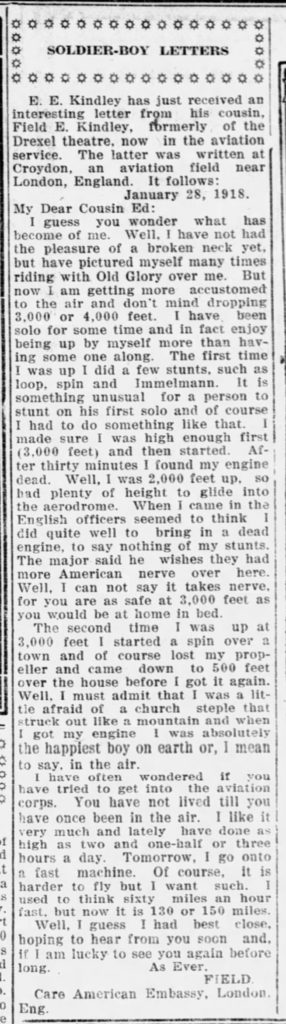

The plane flown by pilot trainees at Northolt was the ubiquitous Maurice Farman S. 11 Shorthorn or “Rumpty,” and when there was “good calm weather flying goes on all day from sunrise to sunset with time out for the instructor to eat and have tea.” In the frequent bad weather, the men put in time at “at wireless, machine gun, bombs, Art. Obs. [artillery observation] classes.”25 Around the first week of December, the men had enough hours to start flying solo: Conrad Henry Matthiessen soloed on December 3, Hooper on December 4, and Kindley, after some bumpy dual flying, on December 8, 1917.26 After just a month at Northolt and about eight hours total flying time, Kindley was posted to No. 40 Reserve [Training] Squadron at Croydon on London’s southern outskirts. There he began flying the next-stage trainer, the Avro. Passages from a letter he wrote from Croydon on January 28, 1918, to his cousin Ed Kindley indicate he was from the first an intrepid flyer:

I have been solo for some time and in fact enjoy being up by myself more than having someone along. The first time I was up I did a few stunts, such as loop, spin and Immelmann. It is something unusual for a person to stunt on his first solo and of course I had to do something like that. I made sure I was high enough first (3,000 feet) and then started. After thirty minutes I found my engine dead. Well, I was 2,000 feet up, so had plenty of height to glide into the aerodrome. When I came in the English officers seemed to think I did quite well to bring in a dead engine, to say nothing of my stunts. The major said he wishes they had more American nerve over here. Well, I cannot say it takes nerve, for you are as safe at 3,000 feet as you would be at home in bed.

The second time I was up at 3,000 feet I started a spin over a town and of course lost my propeller and came down to 500 feet over the house before I got it again. Well I must admit that I was a little afraid of a church steeple that stuck out like a mountain and when I got the engine I was absolutely the happiest boy on earth or, I mean to say, in the air.27

Around this time, Kindley moved on to flying a Sopwith Pup, and on January 29, 1918, he graduated from the first stage of R.F.C. training.28

Kindley’s next station was apparently the aerial gunnery school at Turnberry in Scotland; he later recalled training there for about two weeks.29 From Turnberry he moved a few miles up the coast to Ayr on February 19, 1918, to train in aerial fighting—he was among the first, and perhaps the first, of the second Oxford detachment to arrive in Ayr.30 Four days later he flew a Camel for the first time.31 By this time he had completed sufficient training to qualify for his commission, and Pershing forwarded the recommendation to Washington in a cable dated March 13, 1918; approval came back in a cable dated March 29, 1918.32 The commission apparently did not become official until April 15, 1918, but Kindley knew before then that it had come through. In another letter to Ed Kindley, dated April 12, 1918, he asked “What do you think of me being a first lieutenant?”33

Ferry pilot work

Kindley, like many of his fellow second Oxford detachment members, was eager to get to the front and was frustrated by the pace of A.E.F. bureaucracy. He later recalled that after his training at Ayr, he was “ready for France, . . . but because of the fact that my commission had not arrived, I could not proceed and was held up for a considerable time,” and that “I accumulated about 80 hours by having flown machines from England to France as pilot while awaiting my commission.”34 In fact, his ferry pilot work extended from late March through May, well after his commission was official. In the words of second Oxford detachment member Raymond Watts, the delay arose because “the American authorities had not quite made up their minds what was to be done with us.”35

Ferrying planes was no sinecure; Hooper remarked in early May that “Some of us have had pretty bad luck at this ferrying game.”36 Kindley, in his April 12, 1918, letter to his cousin Ed wrote that “On my first two trips I was the only lucky one out of four to get there altogether, so I decided I was bad luck to the others, so struck out alone. Things went very nicely for a while for a few trips.” However, on about April 6, 1918, Kindley had the first of the three crashes he would experience while ferrying. In the same April 12, 1918, letter to Ed Kindley, he writes that while flying near the Channel, “my engine suddenly cut out with a jerk. Before I knew it I ‘turned up’ and couldn’t get straight before I saw a hedge staring me in the face. Of course I hit it and soon I was out in the middle of a beautiful green field with little bits of an aeroplane all about me.” Having escaped with minor injuries, he “sent the necessary telegrams and phone calls. They asked me over the phone if they should send a truck to gather up the machine. I told them they had better send a small boy with a gunny sack. It is a crying shame to send $12,000 ‘west’ like that, but it’s often done here and little thought of it.” In this same letter Kindley recounts an experience presumably quite unusual for a ferry pilot: he had “been at the front and had a few of the Hun guns pointed at me, for I could see the little gray clouds bursting underneath me. How it happened was that I became lost while trying to locate the aerodrome I was to stop at. I soon got away out of their sight, however, and finally found myself.”

Later in April Kindley got into difficulties while he was flying from Lincoln to Wye; his log book entry reads “fog—soft wheat field—crashed.”37 It is worth noting that, while most of his ferrying involved Camels, Kindley on at least one occasion flew an S.E.5a from England to France.38

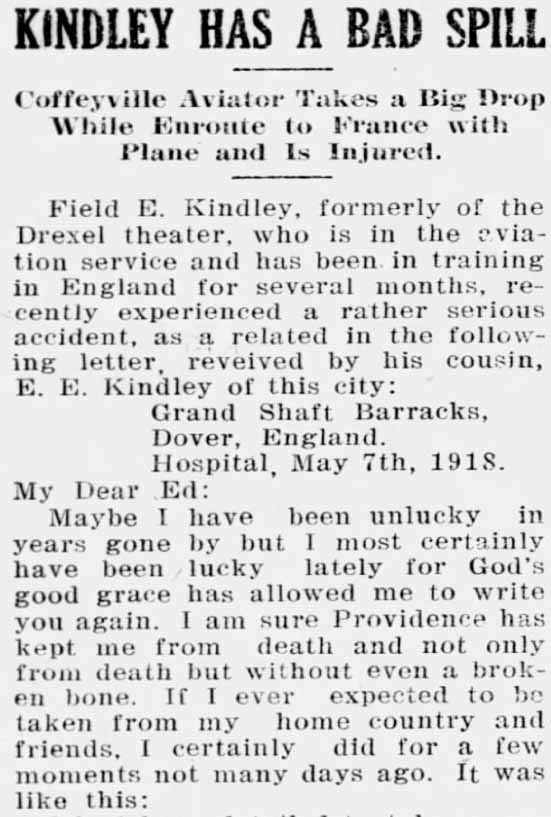

Kindley’s “third and worst fall” occurred early in May 1918. In a letter to Ed Kindley written from the hospital at the Grand Shaft Barracks at Dover Kindley reported that “If I ever expected to be taken from my home country and friends, I certainly did for a few moments not many days ago.”39 Kindley had been asked to fly a plane from an aerodrome in northern England to France, with a refueling stop at Lympne on the English coast. Once over the Channel, he ran into fog. His rather unclear account to his cousin Ed suggests he climbed above the fog only to realize that the aerodrome in France was also covered with mist and that he would have to choose another site to put down; evidently he turned back for England. His engine started to fail and he knew he had to throttle back to keep it from dying completely. He consequently lost altitude.

Very soon my instruments told me I was not over a hundred feet above land or sea. Well, it happened to be sea, for shortly I looked and fifty feet below me I saw muddy water. This told me to stear [sic] west to land, so regardless of vibration and fear of my machine being shaken to pieces, I opened up the throttle and tried to climb higher. It was hard work to gain any speed much less altitude. Shortly I could see the beach about two hundred feet below and before another thought could enter my head I saw something that loomed up like the headlight of a railway engine at night. It was the Dover Cliffs not over twenty-five feet ahead.40

Miraculously, after hitting the cliff and tumbling down, belted into the cockpit, to the beach about two hundred feet below, Kindley came out of the wreckage with only a cut on his forehead and a wrenched shoulder. Watts, who was at Lympne, recollected that an adjutant prepared an initial report indicating Kindley was responsible because he ought not to have attempted a crossing in bad weather, but that the C.O. revised the report to commend Kindley for attempting to ferry a much-needed plane to the front under adverse conditions.41 By May 12, 1918, Kindley was able to write to his cousin Uther “Just a few lines to let you know I have been a lucky boy, and that I am feeling fine and fit” and that he was just “setting here waiting for it to stop raining so I can hop on a street car, run out to my machine just outside of London and take it to France.”42

No. 65 Squadron R.A.F.

Ten days later, on May 22, 1918, Kindley was finally ordered to active duty in France and was assigned to No. 65 Squadron R.A.F. the next day.43 No. 65 was a Camel squadron stationed with the 22nd Wing, V Brigade, at Bertangles, just north of Amiens, which city was, as a result of the first phase of the German Spring Offensive, now only about fifteen miles from the front.44 Kindley was soon joined soon at 65 by Frank William Sidler; they were the only second Oxford detachment members assigned to this squadron.45

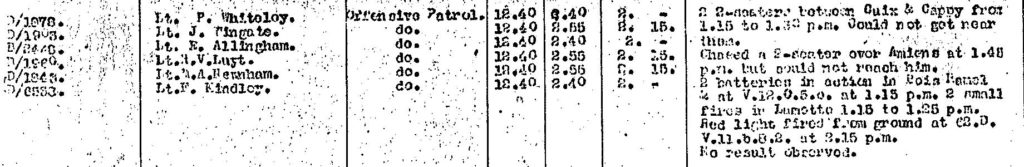

Kindley flew with B flight, led by Canadian Alfred Alexander Leitch. He made his first practice flight on May 25, 1918, in Camel D1899. The next day, after an hour and a half of practicing firing at a ground target in the afternoon, he took B2448 up for forty minutes in the early evening, “learning the country.”46 The R.A.F. typically gave new pilots two or three weeks of orientation before sending them over the lines, and this is what Kindley later described: “They gave me two or three weeks’ training behind the line of battle, detailed for duty as balloon patrols, to watch the balloons back of the line so that the enemy could not shoot them down. I was also supposed to do aerial sentinel work.”47 However, as early as May 29, 1918, he was one of six pilots assigned to an offensive patrol over Albert (in German-held territory); he did not complete the mission only because a broken tail skid on Camel D1878 forced him to turn back a few minutes into the flight.48 The next day he was again assigned to an offensive patrol, and he was one of the six pilots who flew east of Villers-Bretonneux, well inside the German lines, attempting twice, unsuccessfully, to engage enemy two-seater planes.

He flew another “O.P.” the next day; on June 2, 1918, he had aerial sentry duty at 17,000 feet. At some point during this period Kindley had the unnerving experience of encountering “friendly fire.” In a letter to his cousin Ed, he wrote that “Some of our machines mistook us the other day and proceeded to shoot us up. We dare not return the fire for fear it would result in a free-for-all. When at close range they saw our colors and withdrew.”49

On an offensive patrol on June 3, 1918, Kindley had his first encounter with enemy airplanes. In a postscript to the letter to his cousin Ed in which he mentioned being fired on by “our own machines,” he wrote that he had just returned from a patrol and had “had the pleasure of meeting five Hun planes. They had about 3,000 feet height on us and we were over their lines. They drove [sic] on us but did not fight long, until they beat it for home, of course we couldn’[t] follow them nor head them off. We think we got one of them as I saw one machine go straight down to within 1,000 feet of the ground when I lost track of him. Till yet none of us has been credited with this crash. They certainly put up a poor fight with all the advantages they had on us.” In a letter the next day to his cousin Uther, Kindley detailed what was apparently the same encounter: “Yesterday we had a nice interest [sic] scrap over the lines at about 10,000 ft. Three of us happened to be firing at one poor Fritz and now we can not decide who got him but never the less we know he wont [sic] fly on this earth again.”50 Kindley’s squadron mate, George Donald Tod, with Kindley’s confirmation, received credit for one Pfalz driven down out of control over Villers-Bretonneux.51

Kindley wrote to his cousin Ed again on June 9, 1918, to tell him of encounters his flight had had that day with what were evidently observation planes (two seaters) during a two-hour morning patrol that took them east of Moreuil.52 Kindley was fairly confident that he and Leitch (the other members of the flight not having kept up) downed one of them: “the last we saw of him he was settling down to the ground, which caused us to believe we got him,” but the squadron record book notes “E.A. chased East and down to 2,000. feet, but as far as could be seen under control.” There was some consternation that another plane the two of them attacked and one that the whole flight went after did not succumb: “we came to have an awful argument as to why these two seaters did not come down at our fire. It is evident they are armour plated for now they have such machines but we did not think there were any of them on our front.” Kindley remarks with some pride that he kept formation when other flight members were not able to, and he also comments favorably on Leitch: “If you could meet my flight commander, . . . you would think him a prince for he is so nice to us when we do our best or when we even try to do what’s right. He uses his head so much in the air: that is before he attacks, he makes sure everything is with us: no Huns are above us to dive on our tails as we dive on some Huns below. If some man gets lost, like a hen with little chickens, he comes around and picks the lost one up. He is just the kind of a man I like to fight alongside for I know he will stick with me and knowing that makes me stick with him.”

Near the close of Kindley’s letter of June 9, 1918, to his cousin Ed he mentions that “We are expecting another big push on our front, for today a battle was raging on our sector. That means low ground flying, firing into the trenches and dropping bombs on the infantry in groups. It is fine sport but a little hot at times.” It is unclear to me what the “big push” and “battle” were to which Kindley refers. However, 65’s offensive patrol reports for this period include observations of activities in the vicinity of Montdidier, and it is possible that Kindley was referring to the German Matz or Montdidier-Noyon Offensive, which was occurring perhaps within, but certainly very near the southernmost part of the British Fourth Army’s front.

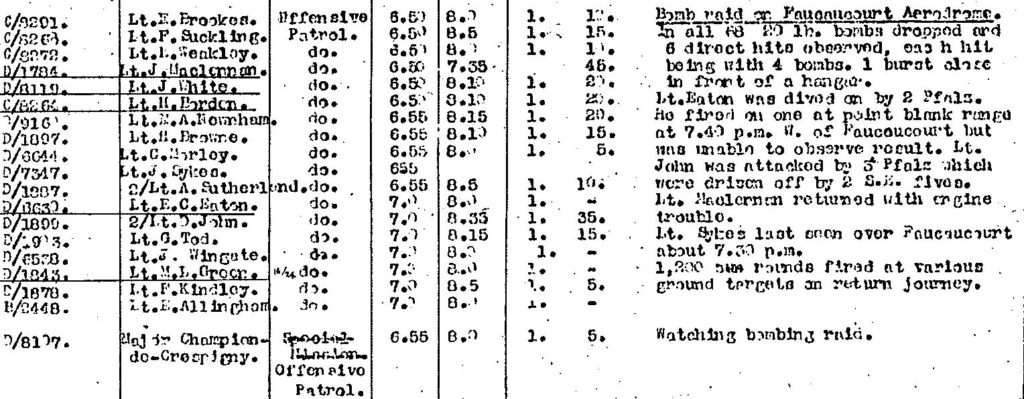

Kindley took part in many patrols in the first half of June, but I do not find any mention of low bombing and strafing in descriptions of them until June 16, 1918. On that day all three flights of No. 65 Squadron, eighteen planes, including D1878 flown by Kindley, set out around 7:00 p.m. and flew twenty-three miles east-southeast to bomb the airdrome at Foucaucourt-en-Santerre, where several German squadrons were stationed. Protected by S.E.5s, they were able to observe six direct hits; they also expended 1200 rounds of ammunition on various ground targets on their return journey. One pilot, John Acton Sykes, was shot down and killed over the airdrome; two pilots, Edward Carter Eaton (who sometimes led B flight in Leitch’s absence) and David Martin John, were unsuccessfully attacked by Pfalz planes.

Ten days after the bombing raid, on June 26, 1918, Kindley, flying Camel D1878, for the first time downed an enemy plane and received credit for it. B flight was on an evening offensive patrol east of Albert when Eaton was attacked by a German Pfalz. Kindley was too late to rescue Eaton, who was “last seen going down under control with smoke issuing from his machine.”53 However, according to Kindley’s accounts of the incident in his combat report and two letters, he was able to shoot down the plane that had attacked his squadron mate and friend. Here is the account in his letter of June 28, 1918, to Ed Kindley:

. . . five of us fliers flying in formation, and led by our fight [sic] commander, Capt. Leitch, M.C., were about four miles over the Huns’ lines and about 12,000 feet high when we saw nine Hun planes above us and, of course, tried to climb up to them when we noticed some “White Archie” west of us (White Archie is ours; Black Archie is Fritzs’ [sic]). This made us think we were being attacked from the rear so we turned to investigate when I noticed about 800 feet below me and to the right, a Pfalz machine close upon one of our machines, which was driven by Assistant Flight Commander Lieut. Eaton, a very good friend of mine. Realizing the danger I at once turned upon the Pfalz only to see Lieut. Eaton go down out of control. I closed in on him, shot a long burst into him from both my machine guns. He half rolled, did a flat spin on his back and then dived straight for the ground. . . . It is not altogether in order for a new man to get his adversary but I just felt that I had to get the damned Hun that shot down my Canadian friend Eaton.54

Leitch and infantry on the ground confirmed Kindley’s victory, and he received credit for one machine destroyed. The pilot of the downed machine has been tentatively identified as Wilhelm Lehmann, the commanding officer of Jagdstaffel 5.55

Trevor Henshaw in The Sky Their Battlefield II notes that Fritz Rumey of Jasta 5 made a “‘Camel’ claim combat eBouzincourt 8-25pm,” and tentatively attaches this claim to the downing of Eaton. In this Henshaw was presumably using the same information that led Norman Franks, Frank Bailey, and Richard Duiven in The Jasta War Chronology to credit Rumey with shooting down Eaton in Camel D6630.56 Given that matching claims and casualties is part art and part science; that Henshaw et al. probably did now know that Kindley stated that he shot down the plane that attacked Eaton; and that Lehman could not make a claim, it is understandable that Rumey’s claim has been matched—or mismatched—with the Eaton casualty, when perhaps Lehmann should have been credited.

After shooting down the plane that had attached Eaton, Kindley climbed back up to his own flight formation and assisted Leitch in downing another enemy aircraft and then attempted to attack two others, “which were almost too much for me so while fighting I worked myself across the lines,” and eventually his pursuers turned back. “I was shaking hands with myself when out of a cloud near by came a Fokker plane (the Huns’ best machines.) Around and around we went neither of us being able to bring our guns into action so he turned east and beat it for home.” Kindley again rejoined his formation at 10,000 feet where they were dived upon by three Albatros planes; unfortunately at this point Kindley’s guns jammed and his engine started giving him trouble, so he withdrew and turned back to the aerodrome, where he landed forty minutes after having taken off on this eventful patrol.57

Kindley flew Camel D1921 over the next days and then tested an apparently repaired D1878 on June 28, 1918, and flew it without incident on a bomber escort patrol the next day. On June 30, 1918, Kindley again flew D1878 on a quiet offensive patrol, his last of some twenty-six offensive patrols with No. 65 Squadron R.A.F.57a

The U.S. 148th Aero Squadron at Dunkirk

On July 1, 1918, Kindley, along with an American squadron mate from 65, Lawrence Theodore Wyly, was transferred to the U.S. 148th Aero Squadron; he was followed shortly by fellow second Oxford detachment members Marvin Kent Curtis, William Thomas Clements, Lynn Humphrey Forster, John Hurtman Fulford, and Walter Burnside Knox. Elliott White Springs, who had been with No. 85 Squadron R.A.F., had arrived at the 148th a few days previously.58 The 148th, stationed at Cappelle Airdrome near Dunkirk, was, along with the U.S. 17th Aero Squadron, American in personnel, but stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until very late in the war when they moved south to the American Front.

William P. Taylor, in his history of the 148th Aero describes how “The Squadron had been assigned nineteen Clerget Camel scout planes [the plane and engine Kindley knew from No. 65]. Soon the pilots, who had been assigned to flights, were practicing daily, sometimes in full squadron formation and then in diving and firing on the silhouetted plane in the marsh nearby at St. Pol.”59

The 148th was divided into the standard three flights, with about six pilots in each.60 Kindley was evidently assigned to A flight, which was led by first Oxford detachment member Bennett Oliver. Springs led B flight, and Henry Robinson Clay, also of the first Oxford detachment, led C.

Taylor continues: “. . . line-patrols were soon started and after careful study of the map, showing this sector from the coast at Nieuport down to Ypres, most of it flat, marshy country, where the Line had been permanent for four years, the patrol-leaders took their charges up to the edge of that awesome place, ‘Hunland’, and let them look it over. As aerial activity was comparatively quiet on this Front, few Huns were sighted. Day after day the line-patrols were practiced without an attempt yet at offensive work.”61

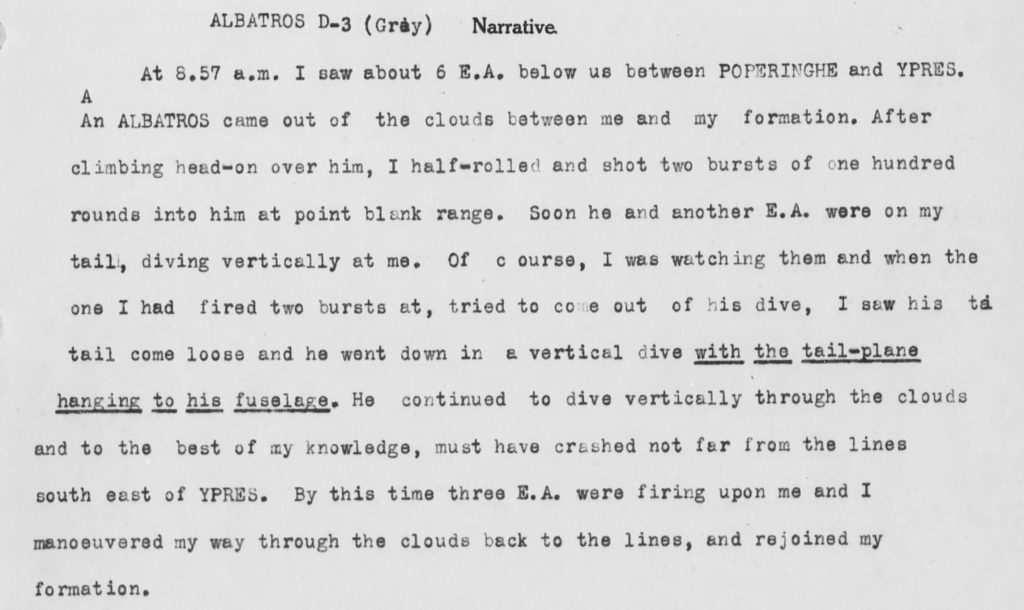

However, it was not entirely “quiet on this Front,” and on the squadron’s fourth line patrol, on July 13, 1918, Kindley, flying Camel D8245, sighted six enemy aircraft below his formation as it flew between Poperinghe and Ypres.

His combat report account is not entirely clear, and Ballard has understood it thus: “Field saw six enemy aircraft below him. While he was contemplating an attack, a German Albatros plane came out of the clouds at Field in his Sopwith Camel.” However, Kindley’s account in a letter to his cousin Ed indicates that the German Albatros was one of the six enemy planes he initially sighted: “. . . I was the only pilot that dived upon the six E.A. enemy planes. . . . Being anxious to be the first pilot . . . to get a Hun I dived on the six Hun machines and, as the report reads [!], I nailed to the cross the first man that came out of the clouds. My guns jammed and before I could clear them this one and another were peppering me with lead. As soon as I saw this Fritz machine going down I looked for some of my allies machines so that they would confirm the ‘hit’ but none of our machines were near. Hun reinforcements had come up in the meantime and soon the whole flock would have been on my tail if I did not make my get-away.” Kindley disappeared into a cloud and zigzagged his way back to the aerodrome. Subsequently “the second army report gave an account of a Hun plane being brought down across our lines at 8:54. My report read 8:57 but my watch was three minutes fast.”62 As Taylor remarks, “The rejoicing was great,” and the congratulations that poured in included a telegram from Brigadier General Edgar Rainey Ludlow-Hewitt, the General Officer Commanding X Brigade (the 148th and the 17th Aero Squadrons were part of 65 Wing R.A.F., which was attached to X Brigade): “Please convey my congratulations to the 148th Squadron and Lieut. Kindley for marking up the first point scored against the enemy by the American Air Service.”63

In his letter to his cousin Ed, Kindley remarked that “this honor might well be called an accident. . . . the reason I was the only pilot that dived upon the six E.A. enemy planes is because the rest of the men were new at the game and it is not wise to lead them into the fray till they can take care of themselves.”64 Kindley’s next victory, which was also the second scored by the 148th Aero, was not an accident.

On July 20, 1918, after about ten days of line patrols, the pilots of the 148th flew their first patrols over the lines,—“real war flying started today.”65 Their task was to escort DH.9s from No. 211 Squadron R.A.F. on their bombing raids on the Belgian coast cities of Zeebrugge and Ostend and on the inland city of Bruges. Most of the patrols were, aside from anti-aircraft fire, routine. On August 3, 1918, however, the escort, which apparently consisted of Kindley’s A and Springs’s B flights, encountered, as Clements of B flight described it,

a little excitement today. We accompanied the bombers over to Bruges. . . . After a rather disagreeable trip there, dodging Archie, and the bombers had dropped their bombs, we turned for home. Four Fokkers biplanes appeared out of a blue sky and immediately sat upon our tail. There were nine camels so they did not care to get down on our level, and we could not get up to theirs. They followed us for about 5 miles waiting for someone to straggle. Someone did and one of the Fokkers went down on him. Our entire bunch of camels turned and went down on the Fokker. Springs was the first and I was right next to him. Springs fired into the Hun and over he went on his back, then went into a vertical dive for the ground. This brought the other Huns down. Kinley [sic] got one of them and the other two were claimed by two other fellows. It was a fast scrap and over in about 5 minutes. All four Huns disappeared. How many of them we got I don’t know.66

Springs and Harry Jenkinson from B flight, and Kindley and Wyly from A submitted claims. Jenkinson’s and Wyly’s were labeled indecisive, but Springs’s and Kindley’s claims were confirmed—Kindley noted in his combat report that “Later I went down under the clouds over Ostend and saw S.E. of Ostend what appeared to be an airplane burning on ground underneath scene of engagement”; whether this was his target or Springs’s is not obvious.67 As Kindley’s encounter occurred, according to his combat report, at 9:38 and Spring’s at 9:40, Kindley was credited with the 148th’s second victory, and Springs with the third.68 Clements’s account suggests Kindley’s watch may still have been running fast. Oliver, originally appointed A flight leader, had gone on leave on July 30, 1918. Kindley had been appointed acting flight commander and was thus leading A flight during this escort patrol.69

The 148th at Allonville

Squadron historian Taylor recounts how “After three weeks of war-flying on the Nieuport-Ypres Front, . . . Major Fowler, who was now in charge of the American Air Forces with the British, asked that [the squadron] be transferred to a more active front. . . . Major Fowler’s request was acceded to, and on August 11th the Squadron was ordered to Allonville Airdrome or Horse Shoe Woods, as it was called, near Amiens,” some seventy-five miles south of Dunkirk.70 Kindley was thus back in the area where he had served with No. 65 and was once again in a squadron attached to the 22nd Wing, V Brigade, R.A.F., supporting the British Fourth Army, commanded by General Henry Rawlinson.71 The Fourth Army, operating on the front from Albert to Roye, had since August 8, 1918, been in the forefront of the Battle of Amiens, the opening push of the Allies’ Hundred Days Offensive. The 148th arrived too late to participate in the major combat of the Amiens Offensive, but it was nonetheless now on a far more active front than the one they had just left.

The 148th remained at Allonville only a week, but flew patrols from Albert south to Roye and Montdidier daily, sometimes twice daily, and engaged in at least five combats.72 Kindley was involved in what was apparently the first of these, which took place early in the afternoon of August 13, 1918, north of Roye. Kindley’s combat report is very brief; the account provided by Taylor is extensive and lively:

. . . Kindley, who was leading, sighted six Hun machines as they approached the lines and at a great distance. Turning northward to give the appearance of not having seen them he waited until they disappeared behind a cloud, still on their way to the lines. Turning, Lieut. Kindley led his flight back across the path he figured the Huns would take and then down through the clouds to attack. The clouds were a huge cumulus drift or fair weather clouds and as the two flights dove out into the clear air, there above, were six Huns, four Halberstadt two-seaters and two Fokker biplanes, The surprise was complete; the two flights, nine machines in all, “zoomed” up into the formation firing as they went. Those in the rear of the Hun formation were doomed, and the pilots killed or wounded, three machines fell out of control. The machines fired on by Lieuts. Kindley, Wyly and Seibold were the ones to fall. The others having heard the shots or having seen in time, turned eastward and by greater speed and dive managed to escape.73

Kindley’s fellow 65 Squadron veteran, Wyly experienced engine trouble and had to land near the front, fortunately on the allied side, a fact that the worried squadron only learned from a telegram the next day. Kindley, concerned that Wyly might have been injured, made a rather hazardous journey to fetch him and found him near the “front line. Wyly had made friends with an anti-aircraft machine gun company and was having the time of his life popping away at Hun planes as they came within range.”74

Two days later, on August 15, 1918, around 4:30 in the afternoon, Kindley’s A flight and Springs’s B flight encountered a large number of Fokkers east of Chaulnes and engaged with them; they shot down possibly as many as six, with three confirmed.75 For a second time, Wyly did not return with the patrol and was reported missing before a wire came stating that he had been wounded, though not seriously, and forced to land. The next day he went to hospital; the same day Kindley headed north for a well-earned two weeks rest.76 A few days later his cousin Ed received a cable: “Having a great time on leave in London. Four Hun planes officially credited.”77

The Cambrai Push

On August 18, 1918, two days after Kindley’s departure for England, the 148th was ordered to Remaisnil, about seventeen miles to the north, and assigned to the 13th Wing (attached to III Brigade) of the R.A.F., supporting the Third British Army, commanded by General Sir Julian Byng. The main thrust of the Allied advance was now being carried by this army, pushing toward Cambrai.78 Starting on August 22, 1918, the squadron undertook, in addition to their escort duties and high offensive patrols, the particularly dangerous work of low bombing and ground strafing. Kindley had had some experience with this kind of flying when he was with No. 65, but it was new for the 148th. On August 26, 1918, while Kindley was away, they got in trouble with it and lost one of his flight members, George Vaughn Seibold.

Kindley returned to the squadron on August 31, 1918, and the next day participated in two bombing raids.79 While with the 148th Kindley been on the relatively quiet front near Dunkirk, and then on a more active front near Amiens, but only after the main push was over. Now he and the squadron were suddenly in the thick of things. “After coming back from leave I found the war in the air had changed. For we were where the battle was raging. The Hun’s best pilots and machines were just across the line from us and every day we engaged them in the air.”80 Kindley’s remarks were prompted in part by an aerial encounter on September 2, 1918, just two days after his return to the squadron. His squadron mate, Springs, wrote this terse description in his log book: “2 September: 1 hour 35 minutes. Canal du Nord. Disaster itself.”81

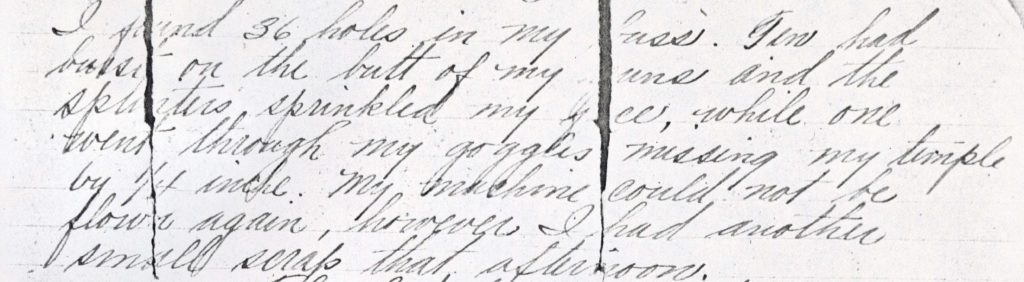

By September 1, 1918, significant advances had been made on the British front somewhat to the south of where the 148th was stationed: Bapaume had been retaken, and the line had advanced as far as Peronne. On September 2, 1918, the Allied focus shifted north, as a successful push was made to break the German’s defensive line between Drocourt and Quéant (the “Drocourt–Quéant switch line,” part of the Hindenburg line), running north to south across the major road between Arras and Cambrai. The 148th Aero was one of a number of squadrons assisting the push. Kindley’s A flight and Springs’s B flight had apparently set out at 11:00 a.m. on an offensive patrol and bombing raid.82 On their return journey, about forty-five minutes later, Kindley’s five-man formation was ahead, while Springs’s flight, still in the vicinity of the Canal du Nord, realized that British planes were being attacked by Fokkers and went to their aid 83 Soon thereafter Kindley’s flight turned back to assist as well. Kindley wrote his cousin Uther: “Nine of us engaged 25 Fokkers. Three of our men have not been heard of because we attacked them [the Fokkers] on their side of the lines. One died of wounds. While we only got two of them.”84 Later accounts suggest that as many as five German planes were shot down, but at a great cost.85 Of Springs’s four-pilot B flight, only he returned: Linn Humphrey Forster had been killed, and Oscar Mandel and Johnson Darby Kenyon taken prisoner. Of Kindley’s five-man flight, two pilots, Joseph Edwin Frobisher, Jr., and Jesse Orin Creech, were forced to land. Frobisher died of wounds eight days later; Creech, having crash landed in Allied territory, was unhurt. The three remaining A flight pilots were each credited with a victory: Walter Burnside Knox with having driven a Fokker down out of control, and Charles Ingoldsby McLean and Kindley each with having destroyed a Fokker.86 This was Kindley’s fifth victory.

Kindley had had a close call. In his letter to his cousin Uther he described finding “36 holes in my buss” and noted that a bullet had gone through his goggles, barely missing his face.87 His Camel, D8245, which he had flown most or all of his time with the 148th, was badly damaged and sent away the next day to be rebuilt.88

For the next two weeks the 148th apparently focused on offensive patrols when the weather permitted, rather than strafing and bombing raids.89 On September 5, 1918, in the late afternoon, Kindley was flying Camel E1539 in a formation at 9000 feet over “St. Quentin Lake” (probably Ecourt St. Quentin) when they were attacked; he was able to drive one of the attackers down out of control, an action confirmed by McLean.90 Spike Irvin noted in his diary two days later that the squadron had “33 Huns to our credit.”91 On this same day, September 7, 1918, Kindley encountered five enemy aircraft while on patrol and was confident of having shot one down out of control, although he did not receive credit for it.92 Over the next few days the weather was mercifully “dud,” but by September 13, 1918, the 148th was again flying offensive patrols, and on September 15 and 17, 1918, Kindley scored his seventh and eighth victories northwest of Cambrai over Dartford Wood and Epinoy respectively.93 During the second week of September 1918 Signal Corps photographers took a number of still and moving pictures in which men of the 148th appeared, including a well-known one of Kindley’s A flight.94

As the German armies fell back to the east, the flying distance from Resmaisnil to the front lines increased, and on September 20, 1918, the 148th Aero was ordered to move east to an airdrome at Baizieux, near Albert. Here they shared patrols with No. 60 Squadron R.A.F., the S.E.5a’s of 60 providing the “‘upper guard,’ while 148 flew low, bombing troops and attacking low-flying Fokkers.”95 Kindley was among eight pilots from the 148th who took part in a bombing raid early in the morning of September 22, 1918, each plane dropping “4 bombs on Marcoing, outskirts along railroad” from 6,000 feet.96

The next week was an extraordinary one for Kindley, one that would earn him the U.S.’s Distinguished Service Cross with Bronze Oak Leaf and the British Distinguished Flying Cross.

On September 24, 1918, a number of the pilots of the 148th, including Kindley, had the “Best fight these pilots were ever in.”97 With an R.A.F. squadron, presumably No. 60 R.A.F., flying protection for them, the three flights from the 148th set out from Remaisnil around 7:00 in the morning and flew east towards Cambrai, about forty-five miles away. Near Bourlon Wood, a few miles over the lines, Clay’s C flight, flying beneath the other two, encountered and engaged a flight of seven “blue-tail” Fokkers. Kindley’s A flight, and then Springs with B flight, dove down to assist.98 According to his combat report, Kindley brought down one of the attacking Fokkers at 7:28, the first of seven victories credited to the squadron that day.99 More Fokkers joined the combat, which, according to Clay, lasted thirty minutes; Springs afterwards reported that men on the ground had counted fifty-three German planes.100 Although many of the 148th’s planes were damaged, some badly, the squadron suffered no casualties. Later in the morning the 17th Aero Squadron, also now assigned to the 13th Wing, had a similar encounter with the “blue-tail” Fokkers with similar success, and congratulations from the highest levels of both British and American aviation added to the squadrons’ celebrations.101

Two days later, on the September 26, 1918, during an early afternoon mission, S.E.5a’s of No. 60 Squadron R.A.F., “ led by [John William] Rayner, drove down a flight of Fokkers into the jaws of 148, who tackled them with such effect that three were ‘crashed’ and one driven down out of control.”102 Kindley claimed a “Fokker biplane, black and white checked, blue tail” destroyed north of Bourlon Wood; this became his tenth confirmed victory.103 Spike Irvin wrote in his diary: “On O.P., Lts. Kindley, Creech, Wyly, and [Orville Alfred] Ralston each get a Fokker. Tomorrow looks like a big day.”104

The “big day,” September 27, 1918, marked the opening of the Battle of the Canal du Nord, the successful attack by the British First and Third Armies on a stretch of the formidable Hindenburg Line about seven miles to the west of Cambrai. The orders for the 148th during the attack specified their working with No. 60 Squadron R.A.F. and focussing, at least initially, on ground targets: “No. 148 American Squadron to work below No. 60 Squadron, and bombs will be carried by No. 148 American Squadron, whose lowest flight should work not above 3,000 feet at the commencement of the patrol. Suitable ground targets such as troops, transport or guns will be attacked. Approaches to the crossings of the Canal de L’Escault and all sunken roads should be specially looked at. Crossings themselves should not be bombed.”105

The morning of the 27th, around 8:40 a.m., the three flights of the 148th took off, accompanied by their escort squadron.106 At 9:00 Kindley dropped his bombs on a railway where transport was visible south of Marcoing and then, with the other members of his flight, attacked an observation balloon before attacking troops on the ground and then, guided by the firing of Allied guns and now flying at just 600 feet, located and silenced a German machine gun. Having climbed back up west to about 2,000 feet, Kindley was attempting to put another enemy machine gun out of commission when he was attacked by a German Halberstadt two-seater, which he in turn attacked and shot down, now flying at 800 feet. He observed and reported Allied tanks and troops “near beet root factory” east of Flesquières. Shortly after 10:00 a.m. he, another member of his flight, and Clay attacked and drove off five two-seater enemy planes that had apparently been trying to ground strafe. Finally, despite having used up all his ammunition, Kindley dove on two enemy aircraft (“two Fokkers picking upon a lone comrade”); his bluff worked, and they turned back east.107 The pilots from both squadrons, 60 and the 148th, returned safely to Baizieux.

Kindley’s actions on the 27th earned him the Bronze Oak Leaf added to the Distinguished Service Cross he was awarded for his attack on the flight of seven Fokkers on September 24, 1918. His actions of both days, as well as leadership of A flight are cited in the British Distinguished Flying Cross Award.108 Kindley’s downing of the Halberstadt on the 27th was counted as his eleventh victory, his only two-seater victory and apparently the only one about which he had misgivings. At the end of November 1918 he wrote to Geo. Jamison that “Only once have I hated to fire and that was when I attacked a two-seater and the observer behind evidently had jambed [sic] guns and he stood up with his hands above his head as if to surrender, but his pilot, was steering homeward so I had to fire. I saw the poor observer’s hands drop and hang over the side. Another burst from my guns and I got the pilot. They went straight down.”109

A. J. L. Scott, in his Sixty Squadron, R.A.F. writes that “During the whole of the advance towards Cambrai and beyond, the two squadrons [60 & 148] did at least one ‘show’ a day together until October 30.”110 According to Taylor, in his history of the 148th, “The work now resolved itself into patrol after patrol ‘with bombs’ and with orders to shoot up targets on the ground with the machine guns. In all sorts of weather, cloudy, misty, rainy or fair the flights went out at low altitudes to perform their work.”111 After his mission the morning of September 27, 1918, Kindley went out again in the early afternoon, targetting Cantaing and Flesquières west of Cambrai; the targets named in his subsequent bombing reports document the eastward movement of Byng’s army. By October 14, 1918, with Cambrai taken and the Allies advancing eastwards, the 148th once again, along with No. 60 Squadron R.A.F., moved, this time to the air field at Beugnâtre, about two miles northeast of Bapaume—Bapaume now “a cluster of ruins in the middle of a desert,” in squadron historian Taylor’s words.112 On October 23, 1918, Kindley dropped four bombs on a road southeast of Bois L’Eveque, seventeen miles to the east of Cambrai.113 In the record of what was apparently his last bombing raid, on October 26, 1918, Kindley’s target is represented by an incomplete map reference, but it was apparently in the vicinity of the Foret de Mormal.114 In a letter to his cousin Uther, Kindley remarked that “While we are pushing we have quite a hard time because not only do we have to fight the Hun in the air but also on the ground, that is we have to fly low and shoot the troops up as well as drop small bombs. After getting down to 500 ft you have to keep flying here and there to keep the machine guns from the ground hitting you. That is if you fly straight they are bound to hit you. It seems mighty cruel to dive down on a bunch of men and shoot them up but it is in the game of war so it must be done.”115

Kindley’s last aerial combat took place on October 28, 1918, just after noon in the vicinity of Villers Pol, about eighteen mile east-northeast of Cambrai.

I was leading the squadron of the flights over the line when I saw the seven Huns and at once set a trap for them. I was leading the bottom flight with two other flights of ours far above me in the sun, out of sight of the seven Fokkers. I led the flight directly below them and was praying and hoping that they would attack. They did attack and got in a few shots before our top flights came down; then there were 14 machines crowded into a small space, each trying to shoot his opponent. I got my Hun and started to get another, but some one beat me to him. By this time every Hun had gone to his grave and we never lost a man. Of course, as leader, I got the credit for the whole show—why, I do not know—for I only did what any one would have done with things in his hands as they were in mine.116

Kindley and Creech between them accounted for one Fokker destroyed, while five other squadron members were also credited with planes either destroyed or driven down out of control.117 As Kindley wrote, the squadron suffered no casualties, although Wyly was forced to land prematurely. The “fight had been a wonderful success and a proper ending to [the squadron’s] war work, since only one more patrol, that without incident in the afternoon, was carried out.”118 Kindley’s joint destruction of the Fokker that day was counted as his twelfth official victory. He and Springs were tied, and their totals were exceeded only by their fellow second Oxford detachment member George Augustus Vaughan (13), and by Frank Luke (18) and Eddie Rickenbacker (25).119

The American front and post-armistice

The men of the 148th had for some time known that they were to be transferred to the American Front, and, in fact, the next day, October 29, 1918, they were ordered to cease war flying and to prepare to move south on November 1, 1918.120 Before they departed, General Charles Alexander Holcombe Longcroft, G.O.C. of III Brigade, visited the squadron and read a letter of thanks and farewell to the 17th and 148th Squadrons from General Byng. There was also a commendation from John Maitland Salmond, Commanding General of the R.A.F. in the Field, who noted the good formation flying demonstrated by the 148th and included a suggestion to his A.E.F. counterpart, Mason Patrick, that the squadron be equipped with S.E.5s.

After several days of uncomfortable train travel from Bapaume through Amiens and Paris the men of the 148th Aero arrived at Toul, where they were attached to the recently formed American Second Army. Kindley wrote his cousin Uther that “We are now operating with our own army and it is fine to see Yankees wherever you turn.”121 The pilots were disappointed to find that they were now expected to fly Spads, contrary to Salmond’s recommendation.122 The 148th, along with the 17th, celebrated the armistice at Toul and then settled in for the long wait for transport home.

On November 28, 1918, Kindley wrote Perry, who had been his partner at the Drexel Theater in Coffeyville, that he had “made application for a commission in the regular army. I was given three months’ leave by a medical board, but after getting my orders for U.S.A., some colonel decided he wanted me to stay over here, offering me the command of a squadron. He also promised to make me captain, and he said I had a good chance to be made a major. Any how, I have command of the Seventeenth Aero Squadron. He is going to give me seven day’s leave in London, so I don’t feel too badly. I shall leave for England tomorrow.”123

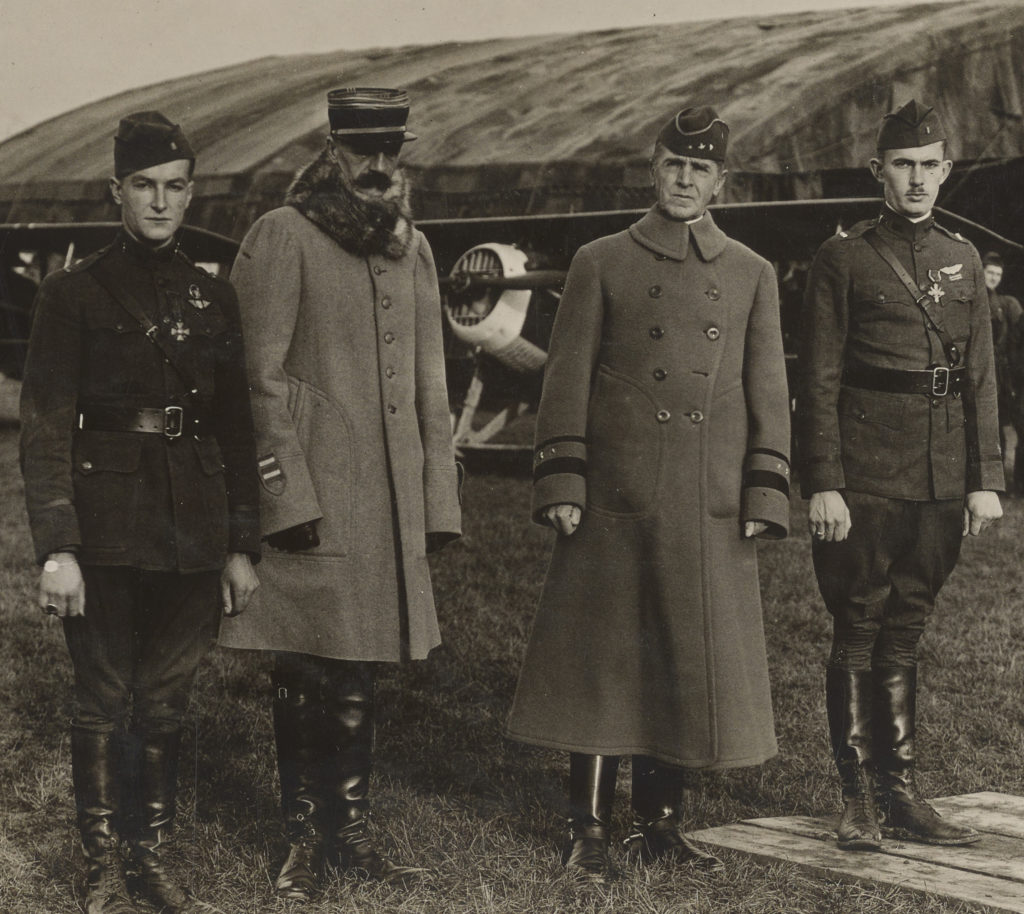

A day or so after Kindley’s return, on December 7, 1918, an awards ceremony–which was filmed—was held at Toul.124 Frank Purdy Lahm, Chief of Air Service of the American Second Army, wrote in his diary that day: “This morning Gen. [Robert] Bullard, with Col. [Bréart] de Boisanger and . . . myself went to the 4th Pursuit Group where General B. was to present a Distinguished Service Cross, with a bronze oak leaf added, to Lt. Kindley of the 17th for some great work he had done on the British front. . . .”125

Two weeks later, on December 21, 1918, Kindley took command of the 141st Aero Squadron, replacing Hobart Amory Hare “Hobey” Baker, who had died that day in an air accident flying one of the squadron’s Spads.126 Kindley’s captaincy came through on February 24, 1919, while he and the 141st were still in Toul.127 In April 1919 the 141st became part of the American Army of Occupation in Coblenz; the perhaps brighter side of this development was that they were able to take over the S.E.5s of the 25th Aero, which was heading back to the U.S.128 Promotion brought with it increased involvement in Army paperwork and bureaucracy; Lahm records going over an Air Service manual with Kindley and others in May 1919, and Kindley wrote a “lessons learned” document as part of the post-war review.129 Finally, in June 1919, Kindley and his 141st squadron sailed home, departing St. Nazaire on the U.S.S. Tiger on June 14, 1919, and arriving at Hoboken on June 27, 1919.130

After Kindley had finished duties associated with disbanding the 141st, he was assigned to Hazelhurst Field on Long Island. From that post he was “sent all over the United States to test and demonstrate new planes” and to promote the importance of aviation.131

On December 12, 1919, Kindley testified before the Aviation Subcommittee of the U.S. Congress House Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department.132 Some of the exchanges are inadvertently droll, as the congressmen and Kindley talk past one another about the respective merits of Camels, Nieuports, Spads, and De Havilland 4s, and as the congresssmen attempt to reconcile Kindley’s remarks with what they have just heard from Eddie Rickenbacker and James Arnold Meissner. But some points stand out clearly in Kindley’s testimony. He stresses the cooperative aspect of formation flying and its importance, wishing he had with him Salmond’s commendation of the 148th’s formation flying: “We did not work as separate airmen, but we went into combat like a basket ball team. If we saw one of our men needed any assistance we went and helped him”; he attributes this successful approach to combat to the training provided by the British and regrets that American pilots not trained by the British did not “realize the importance of cooperating in the air.”133 The congressmen give Kindley several opportunities to mention his own aerial victories and victory count, but Kindley doggedly and modestly reverts to the importance of teamwork. When offered the opportunity to add to the record anything he would like, he points to what he regards as the unfairness in the awarding of Distinguished Service Crosses. He knows “of pilots who have earned a distinguished-service-cross, possibly two or three oak leaves, much more than I have earned and received, and yet they have not received them.”134 He notes that American pilots on the American front had unfairly received disproportionately more of these awards than American pilots who served on the British front, mentioning George Augustus Vaughn and Wyly specifically as among those overlooked.135 His congressional testimony on this topic was followed up by a letter to James A. Frear, chair of the subcommittee.136 Whether as a result of Kindley’s advocacy or not, D.S.C.’s were later awarded to Vaughn (in 1920) and Wyly (in 1923).

That same day, December 12, 1919, Kindley had a more coherent exchange with a congressman at a hearing chaired by Fiorella La Guardia, whom Kindley knew from the voyage on the Carmania in September 1917.137 The subject was a united air service, i.e., one independent of both the army and the navy. Kindley favored such an entity, noting that while attached to the R.A.F. he had been involved in what were essentially naval operations. To La Guardia’s inquiry: “There is no difference in flying whether you are flying over water or over land?” Kindley responded: “There is none.”138

At the beginning of the new year, Kindley was transferred to Kelly Field at San Antonio, Texas, where he was to command the 94th Aero Squadron. On February 1, 1920, during practice for some exhibition flying, Kindley’s S.E.5 crashed, and he was instantly killed. An investigation of the crash did not definitively identify the reason for the crash, but suggested that a broken aileron control wire, a stall in a climbing turn, or wind could have been the cause. Kindley’s friend and 148th Aero Squadron mate, Clayton Bissell, who had witnessed the crash, stepped in to take care of funeral arrangements and accompanied Kindley’s body to Gravette, where Kindley was buried on February 5, 1920.139

mrsmcq August 8, 2018

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Kindley’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Field E Kindley. For his place and date of death, see Ancestry.com, Texas, Death Certificates, 1903-1982, record for Field E. Kindley. The photo is a detail from one taken by Signal Corp photographer Charles Roland Darwin at the ceremony at Toul on December 7, 1918, when Kindley was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (NARA 111-SC-37913).

2 See documents and family trees at Ancestry.com, and Wimberley, The William Kindley Family Genealogy, pp. 1–6.

3 See documents at Ancestry.com, and Wimberly, The William Kindley Family Genealogy, p. 156.

4 See documents at Ancestry.com, and Wimberly, The William Kindley Family Genealogy, p. 156.

5 Wimberly, The William Kindley Family Genealogy, pp. 117 and 156.

6 Ibid, p. 117.

7 Ibid., p. 156, and Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 10.

8 Ibid., p. 156; on his return, see Ancestry.com, Honolulu, Hawaii, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1900–1959, record for Master Field Kindley.

9 I do not find Kindley’s name in the 1910 census, but a letter dated June 28, 1918, from Kindley to his cousin Uther indicates he was living with his “Aunt Mollie” (wife of Amos Erastus Kindley and mother of Uther) from 1908 through 1912 (Kindley, Letters and Reports, 1918).

10 Hudson, “Captain Field E. Kindley,” pp. 4–5, indicates that Kindley completed high school; Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 16, reports that he did not graduate.

11 See “Drexel Theater” and Ballard, War Bird Ace, pp. 16–17.

12 Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 3.

13 See “Joins Aviation Corps” and Hudson, “Captain Field E. Kindley,” p. 6.

14 U.S. Congress, House, Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department, Hearings before Subcommittee No. 1 (Aviation), p. 3823.

15 Scriven, “Report of the Chief Signal Officer,” p. 886 (emphasis added); see also p. 887.

16 See U.S. Congress. House. Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department. Hearings before Subcommittee No. 1 (Aviation), pp. 4035–36 (where the date given in the first item is probably incorrect). See also “More Young Men Wanted for Flying Service in Army.”

17 Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 16, citing a document in the Kindley Records File.

18 “On Way to Skies” and “Likes Flying Corps.”

19 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].

20 See Hooper, Somewhere in France, Chapter 1.

21 U.S. Congress, House, Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department, Hearings before Subcommittee No. 1 (Aviation), p. 3822.

21a Grider, diary entries for November 6 and 13, 1917. In War Birds “Kindley” has been replaced by “Ken”; see diary entry for November 13, 1917.

21b Grider, diary entry for November 14. “To give boot” is to pay interest. In War Birds “Kindley” has again been replaced by “Ken”; see diary entry for November 17, 1917.

22 See Foss, diary entry for November 15, 1917, which lists the men leaving along with their assignments. See Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917, regarding their departure.

23 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917.

24 Hudson, “Captain Field E. Kindley,” p. 6, cites Kindley’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card in the Kindley Records File.

25 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917.

26 On Matthiessen and Hooper, see Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 4, 1917; on Kindley, see Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 24.

27 “Soldier-Boy Letters”; minor corrections have been made silently. Part of this letter was reprinted as “Flier Dodged Church Steeple”; this is presumably the clipping cited by Ballard, War Bird Ace, pp. 26–27.

28 Hudson, “Captain Field E. Kindley,” p. 8, cites Kindley’s R.F.C. graduation certificate in the Kindley Records File. Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 27, citing from Kindley’s log book, also in the Kindley Records File, indicates that Kindley first flew a Pup on January 27, 1918. In his January 28, 1918, letter to his cousin Kindley, remarks that “Tomorrow [i.e., January 29, 1918] I go onto a fast machine.” It is unlikely that he is referring to the Spad VII, the next plane typically used in training at Northolt, but only after more hours on a Pup than Kindley had thus far. Thus it appears that one of the dates relating to his first flight on a Pup must be off.

29 U.S. Congress, House, Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department, Hearings before Subcommittee No. 1 (Aviation), p. 3824.

30 Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 30.

31 Ibid.; Ballard cites Kindley’s log book, as well as a letter Kindley wrote to his father in the Philippines.

32 Cablegrams 726-S and 1008-R.

33 “Letters from Soldier Boys.”

34 U.S. Congress, House, Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department, Hearings before Subcommittee No. 1 (Aviation), p. 3824.

35 Rogers, “Another of the War Birds,” p. 270.

36 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of May 4, 1918. Curiously, there appear to be no casualty cards related to ferrying pilot accidents among the pilots of the second Oxford detachment. Perhaps, as ferry pilots were attached neither to training or operational squadrons, there was no mechanism for reporting their mishaps.

37 Hudson, “Captain Field E. Kindley,” p. 10. See also Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 38. Both writers cite Kindley’s log book in the Kindley Records File, but Hudson gives April 24, 1918, as the date, while Ballard dates it April 20, 1918.

38 Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 38.

39 “Kindley Has a Bad Spill.” Hudson, “Captain Field E. Kindley,” p. 10, dates this incident May 6, 1918, based on Kindley’s log book. The newspaper’s transcription of Kindley’s letter describing the crash “not many days ago” dates the letter, perhaps erroneously, “May 7th, 1918.” Watts, recalling the incident many years later, puts it in April (Rogers, “Another of the War Birds,” p. 271).

40 “Kindley Has a Bad Spill.”

41 Rogers, “Another of the War Birds,” p. 273.

42 Letter in Kindley, Letters and Reports, 1918.

43 “Lieut. Field E. Kindley U.S.A.S.” See also Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 49.

44 On 65’s Wing and Brigade assignments, see Franks and Bailey, “65 Squadron RFC/RAF,” pp. 50 and 51. 22nd Wing and V Brigade were at this time attached to the British Fourth Army, led by Rawlinson. (Numbers for RAF brigades normally corresponded to the number of the army they served. However, the Fifth Army was renamed the Fourth Army on April 2, 1918, in the wake of Rawlinson’s replacing Gough; see Edmonds, Military Operations in France and Belgium 1918, vol. 2, pp. 27–28 and 109.)

45 Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 241 (48).

46 Here and subsequently, details of flights, unless otherwise noted, are taken from RFC/RAF No. 65 Squadron Record Book (4 May 1918–31 July 1918).

47 U.S. Congress, House, Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department, Hearings before Subcommittee No. 1 (Aviation), p. 3824.

48 Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 51 (Ballard cites from Kindley’s log book).

49 “Soldier Boy Letters” [Kindley letter (mis)dated May 2, 1918]; internal evidence indicates this was written June 3, 1918. I do not find a reference to this incident in RFC/RAF No. 65 Squadron Record Book (4 May 1918–31 July 1918).

50 Kindley’s letter of June 4, 1918, is cited by Hudson on pp. 11–13 of “Captain Field E. Kindley”; here p. 12.

51 See the report in RFC/RAF No. 65 Squadron Combat Reports (23 November 1917–1 November 1918).

52 The letter is printed in “With our Soldiers.” See RFC/RAF No. 65 Squadron Record Book (4 May 1918–31 July 1918) for details of time and place.

53 RFC/RAF No. 65 Squadron Record Book (4 May 1918–31 July 1918), entry for June 26, 1918.

54 “Soldier Boy Letters” [Kindley letters of June 28 and July 18, 1918, to E. E. Kindley]. See also the text of a similar letter to his cousin Uther Kindley, reproduced on pp. 13–15 of Hudson, “Captain Field E. Kindley”; also Kindley’s combat report, reproduced on p. 21 of Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F. and in RFC/RAF No. 65 Squadron Combat Reports (23 November 1917–1 November 1918). In the latter the report is misdated “30.6.18.”

55 Franks and Bailey, Over the Front, p. 49; Shores, Franks, and Guest, Above the Trenches, p. 223.

56 Franks, Bailey, and Duiven, The Jasta War Chronology, p. 194. See also Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, p. 132.

57 Quotations are from Kindley’s letter to his cousin Ed of June 28, 1918; similar passages appear in his letter of the same date to his cousin Uther (see earlier note).

57a I am aware of only one photo depicting Kindley while he was with No. 65 Squadron. It apparently belonged to Frank Aloysius Dixon and was reproduced on p. 44 of Miller, “USAS Fliers with the RFC/RAF, 1917-1918.”

58 See the roster of officers of the 148th on pp. 61–63 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron.

59 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 25.

60 There does not appear to be a reliable listing of the men in each flight for any given date, much less the kind of detail provided for the flights of the 17th Aero by Reed and Roland in their Camel Drivers. But see “148th Aero Squadron Pilot rosters by Flight.”

61 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 26.

62 Letter of July 18, 1918, reproduced in “Soldier Boy Letters” [Kindley letters of June 28 and July 18, 1918, to E. E. Kindley].

63 Ibid.

64 See also Kindley’s account on p. 3826 of U.S. Congress, House, Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department, Hearings before Subcommittee No. 1 (Aviation), where he explains that he and the flight leader, presumably Oliver, were the only experienced pilots.

65 Entry for July 20, 1918, in Irvin’s diary in Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section.

66 Clements, “World War Diary of W. T. Clements 1917-1918,” entry for August 3, 1918.

67 On Jenkinson’s and Wyly’s combats being designated “indecisive,” see Irvin’s diary entry for this day in Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, as well as their combat reports on pp. 40 and 41 of Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F. The time stated for Kindley’s combat on the report in Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F. (p. 45) is 9:38. It is reported as “9:30″ in the copy on p. 94 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron.

68 See Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F., p. 45 for Kindley, p. 42 for Springs. Kindley’s combat report on p. 94 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, gives 9:30 as the time.

69 On Oliver’s departure, see Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 22 & 77. Kindley’s letter of September 30, 1918, to his cousin Uther (in Kindley, Letters and Reports, 1918) documents his having become an “honest to God Flight Commander,” but does not supply a date for the change of status.

70 Ibid., p. 28.

71 On the 148th, the Fourth Army, and the 22nd Wing, see Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 29 and 79; see also Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 469. Taylor’s history reproduced in Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, inadvertently, p. 26, puts the 148th with the Third British Army, and this was presumably the source of confusion for Skelton and Williams on p. 98 of their biography of Henry R. Clay.

72 See the transcription of Springs’s log book for this period on pp. 198, 200, and 202 of Springs, Letters from a War Bird. I have not found anything like a squadron record book with records of all flights made by the 148th.

73 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 29; Kindley’s combat report, which claims a two-seater driven down out of control, is on p. 97 and lacks the notation “decisive,” as does the copy (with minor differences in the narrative) on p. 61 of Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F. The entry for Kindley on p. 207 (22) of Munsell, “Air Service History,” indicates “1 E.A. destroyed” for this date.

74 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 30.

75 See combat reports for Jesse Orin Creech, George Vaughn Seibold, and Harry Jenkinson, Jr., on pp. 99–101 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron. Jenkinson’s decisive claim this day seems to be overlooked in victory lists (see relevant sections of Victories and Casualties); the entry for him on p. 212 (27) of Munsell, “Air Service History,” does not mention it.

76 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 31 and 79 on Wyly, p. 79 on Kindley.

77 “Kindley Gets Hun Planes.” On his London leave, see also Kindley’s letter of September 30, 1918, to his cousin Uther Kindley (in Kindley, Letters and Reports, 1918).

78 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 31; the 148th’s bombing reports, arranged chronologically, are on pp. 161-244.

79 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 81.

80 Letter of September 30, 1918, to his cousin Uther Kindley (in Kindley, Letters and Reports, 1918).

81 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 221.

82 For the start time, see the entry for Kindley on p. 214 of Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II. For an account of R.A.F. assignments during this push, see Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, pp. 492–95; unfortunately, he does not here indicate what role the 148th Aero was expected to play. While Henshaw and the relevant combat reports label the flights’ activity an offensive patrol, Taylor, in his history of the squadron published in 1974, writes that “‘A’ and ‘B’ Flights were returning from a bomb-raid” (Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, p. 33). Bomb report number 28, which may have described the mission, is lacking in both Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron (in Gorrell), and the 1974 Taylor and Irvin publication. (On the sometimes non-distinction between offensive patrols and bombing raids, see Meech’s postings at “Offensive patrol vs. bombing/strafing patrol.”) Typically Taylor’s narrative account of the 148th is much the same in the version published in Gorrell and in the 1974 publication; however the account of this raid is not the same in both publications. The account on pp. 34–35 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron focuses on Springs, while the later version focuses on Kindley. Part of Springs’s combat report, otherwise apparently not extant, is reproduced in Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 499. See also Springs’s account of the raid in his September 3, 1918, letter to his father (Springs, Letters from a War Bird, pp. 221–23).

83 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 498, identifies the British planes as S.E.5a’s from No. 64 Squadron and Bristol Fighters from No. 22 Squadron.

84 Letter of September 30, 1918, to his cousin Uther Kindley (in Kindley, Letters and Reports, 1918).

85 See Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, p. 215.

86 The combat reports are reproduced in Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 116–18. Knox’s combat report reproduced on p. 118 of Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F. credits him with having destroyed an enemy plane.

87 See also Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 221, in a letter (mis-)dated September 1, 1918.

88 Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, p. 139.

89 See the bombing reports in Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, which jump from No. 27 on September 1, 1918, to No. 29 on September 16, 1918 (pp. 191–92).

90 See the combat report on p. 122 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, as well as Irvin’s diary entry for Sept. 5, 1918 (Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, p. 16). Ballard, War Bird Ace, Chapter 6, endnote 21, notes that Kindley recorded this encounter under September 6, 1918, in his flight log.

91 Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, p. 16.

92 See Ballard, War Bird Ace; p. 85; Ballard’s account is based on Kindley’s log book (Kindley Records File)..

93 See combat reports on pp. 124 and 132 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron (the September 15, 1918, report is missing from Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F.). Irvin, in his diary entry for September 14, 1918, writes that “Kindley brings down one Fokker” (Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, p. 16). Irvin is probably noting Kindley’s Fokker out of control over Dartford Wood; either Irvin’s date or the date of the combat report is incorrect. As Ballard notes no discrepancy between the combat report and Kindley’s log book, it seems more likely that Irvin’s date is off.

94 For the still pictures, see Catalogue of Official A.E.F. Photographs Taken by the Signal Corps, pp. 273–74; digitized images are now avaiable at the National Archives and Records Administration web site. For the moving pictures, see “Aviation Activities in the A.E.F., Miscellaneous Scenes [1918].”

95 Scott, Sixty Squadron R.A.F., p. 117. On the 148th’s cooperation with 60 as well as with No. 201 Squadron R.A.F. at Baizieux, see also Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 36. On the initiation of and rationale for these two squadron patrols, see Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, pp. 506–07.

96 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 194–95.

97 Irvin, diary entry for September 24, 1918 (Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, p. 17).

98 On the possible identity of these enemy planes, see “Blue-tail Fokkers, Sept. 24, 1918.”

99 See combat reports on pp. 136–42 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron and the narrative account on pp. 39–40. All the combat reports other than Kindley’s have times of 7:30 or later; one wonders whether Kindley’s watch still fast or whether he was perhaps more precise in his notation of time.

100 Skelton and Williams, Lt. Henry R. Clay, p. 128; Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 243.

101 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 40. See “Blue-tail Fokkers” on the corresponding German casualties (or lack thereof).

102 Scott, Sixty Squadron, R.A.F., pp. 117–18.

103 Kindley’s combat report is on p. 145 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron.

104 Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, p. 17.

105 Playfair, 13th Wing Special Operation Order No. 12.

106 Hudson, “Captain Field E. Kindley,” p. 22, provides the time, based on an account by Kindley titled “A Day in France” in the Kindley Records File.

107 See Kindley’s detailed combat report on p. 148 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, as well as the account provided by Hudson, Captain Field E. Kindley, pp. 22–23, which in turn is based on Kindley’s “A Day in France” and “An Oak Leaf Job,” the latter, the source of the quotation, was also in the no longer extant Kindley Records File.

108 The texts of the awards are reproduced on p. 164–65 of Ballard, War Bird Ace. See also Munsell, “Air Service History,” pp. 168–69, for the D.F.C. citation; and “Awarded Distinguished Service Cross.”

109 Letter to Jamison reproduced in “With our Soldiers.” Jamison was presumably George Washington Jamison, whom Kindley had known in Coffeyville, Kansas. .

110 P. 118.

111 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 40.

112 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, quotation taken from p. 41; date from p. 42.

113 See bombing reports 33 ff. in Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 198 ff.

114 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 243 (report No. 59).

115 Letter of September 30, 1918, to Uther Kindley, in Kindley, Letters and Reports, 1918. Kindley’s tone regarding ground strafing is much more flippant in the letter he wrote to Geo. Jamison in late November (reproduced in “With our Soldiers”).

116 From Kindley’s letter of November 10, 1918, to his cousin Uther Kindley, printed in “Arkansas ‘Ace’ Downed 11 ½ Huns.” See also Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, for another account of this engagement.

117 See the combat reports for Laurence Kingsley Callahan, Clayton Lawrence Bissell, Thomas Lewis. Moore, Creech, and George Chadsey Dorsey on pp. 155–59 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron.

118 Ibid., p. 49.

119 Thayer, America’s First Eagles, p. 316; cf. Victories and Casualties, p. 50, which includes Lufberry, with 17.

120 Taylor, A History of the 148th Squadron, pp. 48 and 52.

121 From Kindley’s letter of November 10, 1918, to his cousin Uther Kindley, printed in “Arkansas ‘Ace’ Downed 11 ½ Huns.”

122 Taylor, A History of the 148th Squadron, pp. 53–54.

123 The letter is reproduced in “Kindley to Stay in Army.” It is one of at least four letters Kindley wrote that day with generally the same news. Ballard, War Bird Ace, pp. 108–09, cites from Kindley’s letter to his father. A letter to his cousin Uther is in Kindley, Letters and Reports, 1918. His letter to Geo. Jamison is printed in “With Our Soldiers” [Kindley letter of November 28, 1918, to Geo. Jamison].

124 “Aviation Activities in the A.E.F., Miscellaneous Scenes [1918]”; the ceremony appears in the last quarter of reel 3.

125 Lahm, The World War I diary of Col. Frank P. Lahm, Air Service, A.E.F., p. 153.