(Evanston, Illinois, November 24, 1893 – Palm Beach, Florida, August 8, 1982).1

Mudge was, like myself, descended on his father’s side from Jarvis Mudge, one of the founders of Hartford, Connecticut, and on his mother’s from William Hersey, who emigrated from Reading, England, to the Massachusetts Bay Colony around 1635.2 Some of the Herseys settled in Maine, where Mudge’s great-grandfather, Samuel Freeman Hersey, was a prominent politician and “lumber baron”; his son, Roscoe Freeman Hersey, came to Minnesota to look after and expand the family lumber business.3 Some of the descendants of Jarvis Mudge settled on Long Island in what is now Roslyn Harbor; the “Mudge Farmhouse,” built around 1740, is on the National Register of Historic Places.4 Mudge’s grandfather, Daniel Coles Mudge, was born in Oyster Bay, not far from Roslyn Harbor, and died in Yonkers in Westchester County; he spent much of his business career in St. Louis and in Philadelphia, where his son Daniel Archibald Mudge was born. D. A. Mudge married Eva Estelle Hersey in 1889 in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he looked after his father-in-law’s timber interests; the couple had four children; Dudley Hersey Mudge was the second child and first of two sons.5

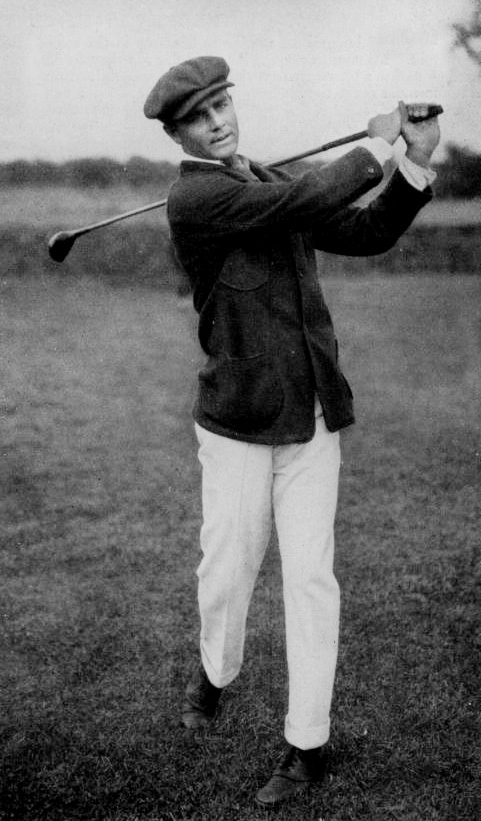

One of Mudge’s aunts on his father’s side, Lizzy Eddy Mudge, married Scottish-born John Reid, who is sometimes described as the father of American golf. This branch of the family evidently had quite an influence on the young Dudley Hersey Mudge, who in 1908 became the first junior member of St. Paul’s Town and Country Golf Club; soon his name was appearing prominently in newspaper reporting on golf.6

Mudge attended Hotchkiss School in Connecticut and then Yale, where he went out for baseball and hockey as well as golf. He would have graduated with the class of 1916, but “He left College junior year because of ill health and returned the next year, enrolled as a member of 1917.”7 Ill health did not affect his game: “Mudge earned national headlines in 1915 when he led the qualifying round at the U.S. Amateur in Detroit. That was the year that Mudge won the first of his two consecutive Minnesota State Amateur [golf] Championships.”8

Not long after the U.S. entered the war, Mudge was at officers training camp at Fort Snelling, Minnesota.9 He applied successfully for the aviation section of the signal corps; on July 1, 1917, he was in charge of a group of ten men setting out for Columbus, Ohio, and the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University.10 He graduated from ground school there with the class of September 1, 1917.11

Along with most of his O.S.U. classmates, Mudge chose or was chosen to train in Italy, and he joined the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania, departing New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917. They travelled first class, and Mudge was assigned to an outside stateroom, C.47, along with Joseph Frederick Stillman and Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, who had been in the class ahead of him at O.S.U., and William Hamlin Neely, who had attended ground school at Princeton.12 The Carmania made a brief stop at Halifax, and then set out as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. For much of the voyage the men’s only obligations were boat drills and daily Italian lessons taught by Fiorello La Guardia. Once the convoy entered dangerous waters around September 27, 1917, they took turns at submarine watch. On September 29, 1917, Neely noted in his diary that he had been paired with Mudge: “We had the fourth post which is at the starboard end of the aft navigating bridge. We saw nothing exciting.”

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. As much of their class work repeated material already covered in the U.S., the cadets (as they were now called) did not have to study hard, and they enjoyed exploring Oxford and the surrounding countryside. There was also, according to accounts in War Birds, a good deal of carousing. Julian Carr (“Jake”) Stanley “gave a party at Buol’s” to celebrate his birthday. “It was a right good party. He had a private room on the third floor and there were present: Cal [Laurence Kingsley Callahan], [Elliott White] Springs, [James Whitworth] Stokes, Paul Winslow and his brother Alan, Hash [Harold Hatch] Gile, Dud Mudge, an English staff officer and myself. . . . Everybody was all teed up before they got there and then we had cocktails by the quart and champagne and then each man got a half-gallon pitcher of ale. We sang that old song and made everybody do bottoms-up by turn.”13 Stanley’s birthday was October 22, 1917, but the War Birds entry indicates that the party was held on Saturday the 20th, the same evening the men of the first Oxford detachment, pleased with their exam results and their impending departure from Oxford, staged a bibulous celebration that greatly annoyed the British authorities. In consequence all the Americans were ordered to move into the same college, Exeter, rather than remaining divided up between Christ Church and Queen’s. Milnor wrote that at Exeter “Fred [Stillman], Jake Stanley, Dud and I had a large room on the ground floor.”14

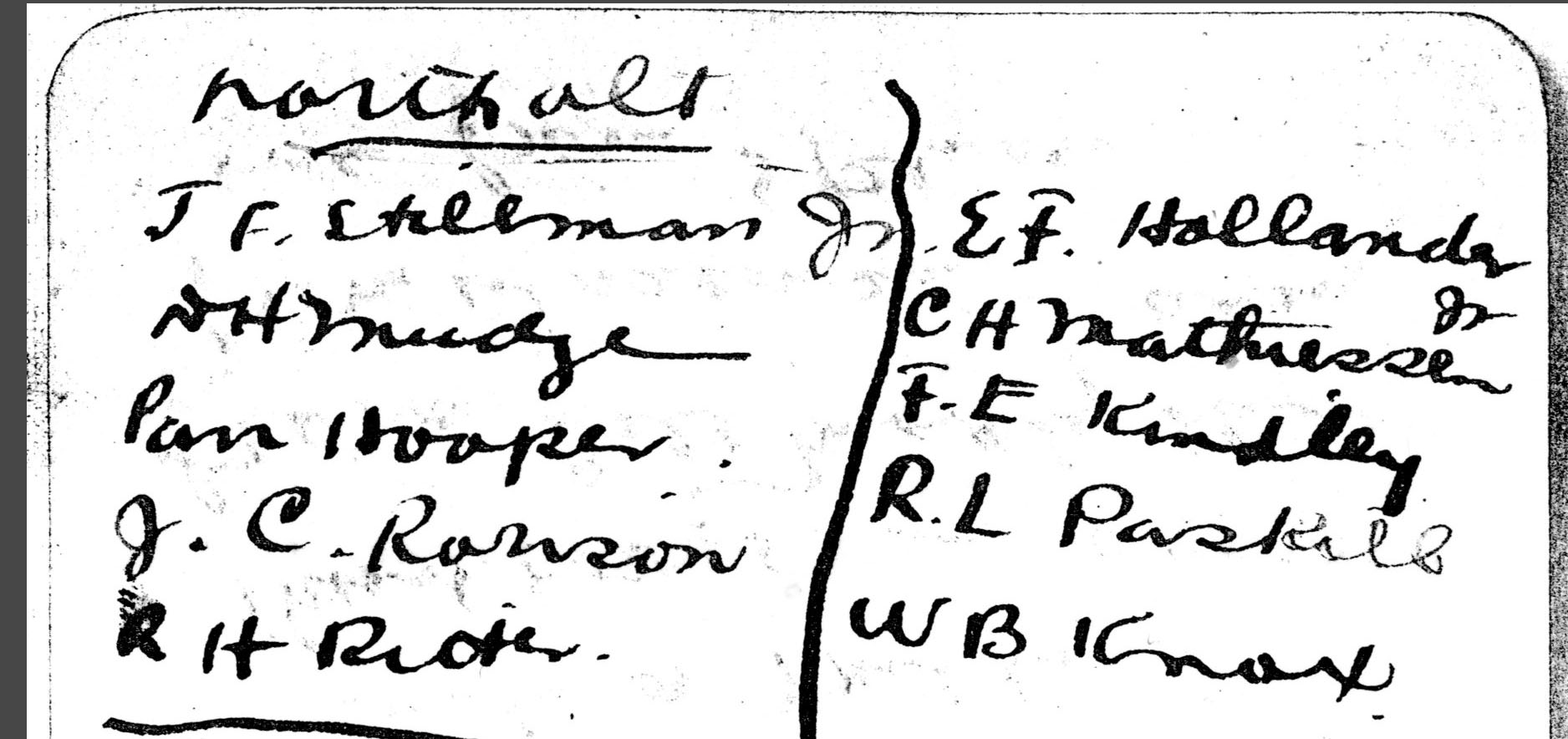

The men were eager to start flight training, and in early November twenty of them were able to go to Stamford for instruction. But, because there was a severe shortage of training places and equipment, the other men were ordered to a machine gun school, Camp Harrowby, near Grantham in Lincolnshire. They arrived November 3, 1917, and, Parr Hooper, who had been in the class ahead of Mudge at O.S.U., wrote home the next day that “We will be here 4 months”15—like so much information passed around among the detachment members, this turned out to be incorrect. Ten days later, Hooper wrote that he had “some good news. This morning when we fell in to go on the range, Capt. Hibbard, our C.O. (Commanding Officer, British) read out the 50 names of the men who go to flying schools next Monday.” Hooper’s name was on the list, as was that of “Dud Mudge who I particularly admire.”16 There was some initial confusion as to which men would go where, but in the event, Mudge and Hooper were among ten men posted to Nos. 2 and 4 Training Squadrons at Northolt airfield in Ruislip on the northwest outskirts of London.

Hooper describes their journey from Grantham to Northolt on November 19, 1917: “We packed up Sunday evening and loaded our luggage on motor lurries [sic; sc. lorries] at sunrise Monday. The train for London left at 7:30. We had a 1st class compartment and read the papers and watched the scenery. We arrived at King’s Cross Station unexpectedly soon 10:45. Fred and Dud Mudge went up to Paddington Station with our luggage on horse drawn busses. . . . we took the train for Northolt at 1:57 from Paddington. . . .We got to Northolt about 4 and after visiting headquarters had tea in our mess and then got our billets and baggage arranged.”17

The men quickly learned to take advantage of their proximity to London’s amenities; two days after arriving at Northolt, Hooper writes from the “Piccadilly Hotel where I am going to the Grill Room and have dinner with Fred Stillman, Dud Mudge and Robert [sic; sc. Roland Hammond] Ritter. Dud has just come.”18

Weather at Northolt was initially poor, but on November 22, 1917, Hooper went up for his first flight, and presumably the other men also began instruction around the same time. “In good calm weather flying goes on all day from sunrise to sunset with time out for the instructor to eat and have tea. The elementary squadrons use a very old type machine but one which they say is excellent to learn on because it has no inherent stability and must be flown (meaning controlled) all the time.”19 The “old type machine” was the Maurice Farman S. 11 Shorthorn, often referred to as a Rumpty or Rumpety. These were “pusher” biplanes (i.e., ones with the propeller mounted behind the cockpit) and had been developed before the war and used on the Western Front into 1915; in 1917 they were ubiquitous in elementary training.

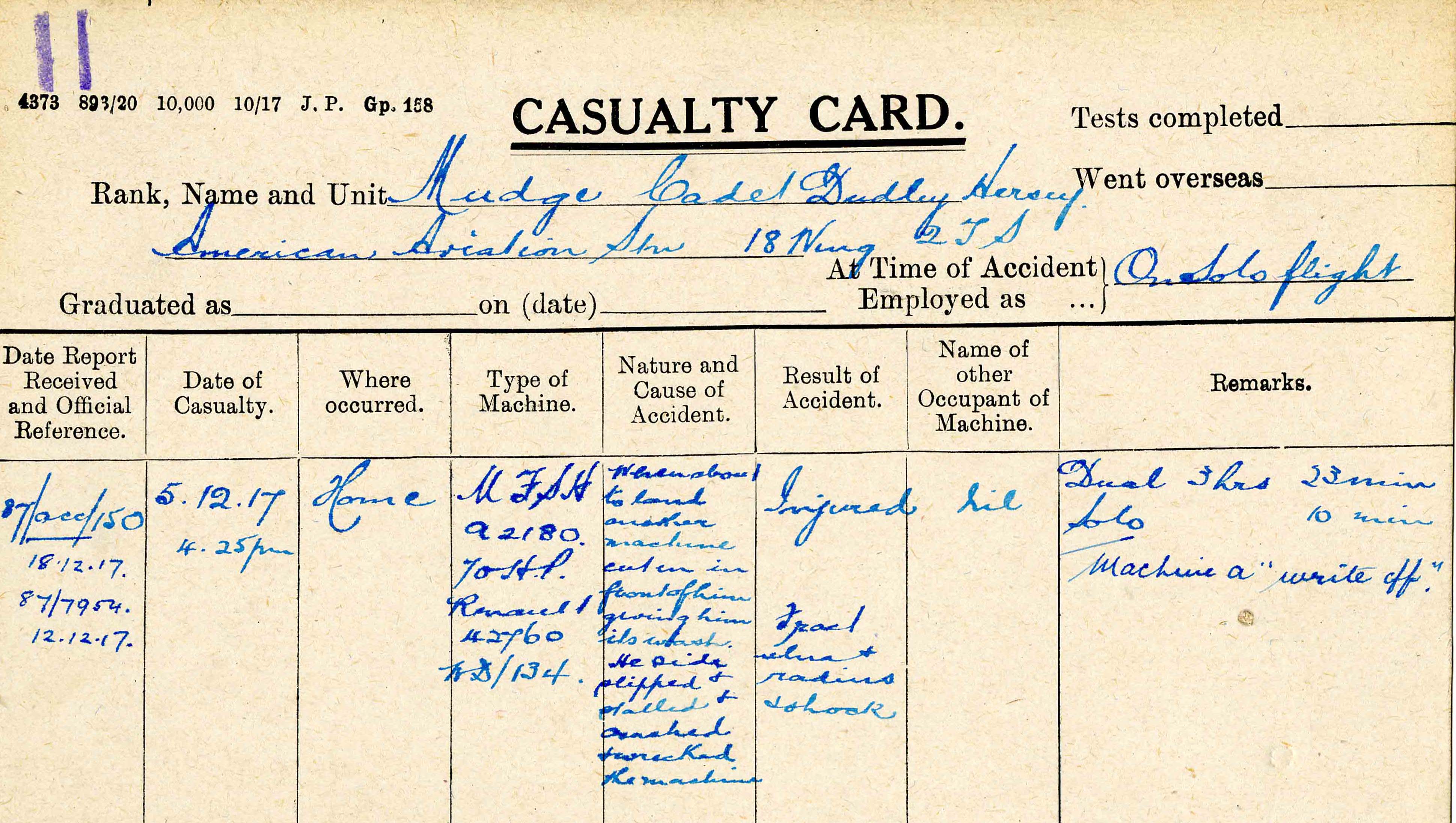

By December 5, 1917, Mudge had three hours and twenty-three minutes of dual instruction under his belt. Two days previously Conrad Henry Matthiessen had flown solo, and Hooper made his first solo flight the next day.20 On the 5th, a little before 4:30 p.m., Mudge took off in M.F. S.H. A2180 for his first solo flight. “When about to land another machine cut in in front of him giving him its wash. He side slipped & stalled & crashed & wrecked the machine”—this is the official description of the crash on the relevant R.F.C. casualty card.21 Mudge suffered a broken forearm (both radius and ulna) and shock, but, given that the machine was a “write off,” was fortunate to have fared no worse in this, the first plane crash involving a member of the second Oxford detachment.

There is a description of the crash in War Birds—comparison with the casualty card cited above and Hooper’s recollection (below) suggests that rumor and the desire to tell a good story played their part when this account was written:

Dud Mudge had a funny crash over at Northholt. He was up on his first solo in a Rumpty and lost his head coming in and flew right into the side of a hangar. The nacelle came on through and pitched Dud on the floor. A mechanic was at work in there and was smoking and he was so frightened at being caught smoking in a hangar that all he could do was to stammer and make excuses while poor Dud lay on the floor with a broken arm. The engine was full on outside and the throttle was on the inside and before anybody could get to it, the Rumpty slowly pushed the side of the hangar in and the roof fell on top of it. No one could get to the throttle then and it ran until the cylinders overheated and froze up. It must have been a funny sight to see that box-kite pushing madly at that hangar and then jump on top of it.22

Hooper, in a letter to his parents early in the new year, wrote that: “Dud Mudge was on his first solo, at Northolt in a Rumptie. When he was gliding down over the shops and hangers [sic] to land another machine came a bit close in front of him. He tried to turn away but stalled his bus and took a nose dive into a sail maker’s shop. Going down he put on his engine. The nacelle, the enclosed body that contains the pilot and engine, went through the wall just below the eaves, and the rest of the machine crumpled up outside. Dud was a bit bewildered and climbed out of the bus while one of the sail makers turned his engine off.” Hooper goes on to say that the crash “occurred just at dusk. I was feeling a bit too sentimental about the wreckage to take a picture of it, but after supper I went back and took a flash light of the nose of the nacelle from the inside of the hut. You can see how it came in where a window was. The window frame was hanging on the nacelle as shown in the picture.”23

About a week after Mudge’s accident, Hooper was in London and, after visiting the Science Museum in South Kensington until it got dark, “went to the R. F. C. Hospital and visited Dud Mudge”—this was perhaps the R.F.C. hospital at 82 Eaton Square in Belgravia, not far from the Science Museum. “His arm is getting along O.K. He is being very well cared for and was in excellent spirits. He is going to get a job in connection with the embassy while his arm is getting well and then is coming back to flying.”24

In early April 1918 Mudge was one of a large number of cadets whose names were forwarded by Pershing to Washington with the recommendation that they be appointed “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying.”25 The “non flying” stipulation had nothing to do with Mudge’s broken arm and interrupted training; rather, Pershing had been made aware that, due to insufficient training facilities, many would-be pilots in England were falling behind their stateside counterparts in gaining commissions, and he was recommending to Washington that the affected men receive commissions as first lieutenants aviation reserve; Washington agreed, with the stipulation that they be put on “non flying” status and transferred to flying status once they completed training.26 A cablegram dated May 13, 1918, included Mudge’s name among those whose commissions had been approved.27 Mudge was two weeks later placed on active duty.28

In the meantime, Mudge’s roommate from the Carmania and Exeter College, Milnor, also unable to continue flying training, had started working at American Aviation H.Q. at 35 Eaton Place in London; he wrote in his diary on May 4, 1918, that “We had a sort of Columbus reunion at luncheon at the Knightsbridge. Dud Mudge, Pat, Earl Adams, Red [Guy Samuel King] Wheeler, [Malcolm Leland?] McGuckin and myself.”29 Towards the end of the month, Milnor noted that “Dud went up to Lincoln with Jake Stanley to fly back and also to see if he still wants to fly.”30 The answer was evidently “Yes,” because three days later, according to Milnor, “Dud left for Oxford at 4:30 to No. 35 T.S. to fly Bristols.”31 Mudge would have been somewhat familiar with No. 35 Training Squadron, which had been at Northolt while he was there; it moved to the aerodrome at Port Meadow west of Oxford shortly after his accident.32 Mudge was to train on Bristol F.2 Fighters, two-seater planes intended for reconnaissance as well as fighting. Milnor met up with Mudge when he had business to take care of at Oxford, and Mudge occasionally dined with Milnor back in London.33

I find no further information on Mudge’s training; he was apparently not posted to an operational squadron and remained in England. Like a number of other second Oxford detachment men who were in England when the war ended, he was able to leave from Liverpool for the U.S. on November 25, 1918, on the Mauretania; also on board were Robert Alexander Anderson, Bonham Hagood Bostick, Walter Chalaire, Raphael Sergius De Mitkiewicz, Alfred August Gaipa, Bradley Cleaver Lawton, John Warren Leach, Milnor, Francis Kinloch Read, Homer Ireland Smith, and Lynn Lemuel Stratton.34 There was much fanfare when the Mauretania arrived at Hoboken on December 2, 1918, as she carried the first American troops and aviators to return from Europe after the war.

After the war Mudge settled in Chicago where he became an advertising executive.35

mrsmcq October 9, 2020

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

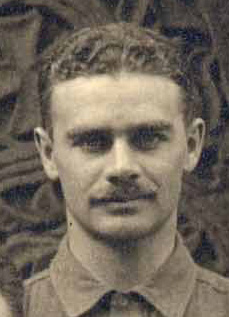

1 Mudge’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Dudley Hessey [sic] Mudge. His place and date of death are taken from “Funeral Notices,” The Palm Beach Post. The photo is a detail from the group photo of Mudge’s O.S.U. ground school class taken by Frank Hager Haskett on August 13, 1917.

2 On Jarvis Mudge and his descendants, see Mudge, Memorials, and Jacobs, “Jarvis Mudge, Hartford Founder”; on William Hersey, see Biographical Sketches of Representative Citizens of the State of Maine, p. 331.

3 See Wikipedia, “Samuel F. Hersey”; and “Roscoe Freeman Hersey.”

4 See Wikipedia, “Mudge Farmhouse,” and “1982 House Tour Guide,” pp. 71–81.

5 See documents available at Ancestry.com for information on Mudge’s family.

6 Shefchik, From Fields to Fairways, p. 15.

7 Oliver, ed., History of the Class of Nineteen Hundred and Sixteen Yale College, p. 298.

8 Shefchik, From Fields to Fairways, p. 15.

9 McGuiness, Among the Golfers.”

10 “Recruits are Wanted for Signal Service.”

11 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

12 Milnor, diary entry for September 18, 1917.

13 War Birds, entry for October 22, 1917.

14 Milnor, diary entry for October 22, 1917.

15 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 4, 1917.

16 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November [14], 1917.

17 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917.

18 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 21, 1917.

19 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917.

20 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 4, 1917.

21 “Mudge, D.H. (Dudley Hersey).”

22 War Birds, entry for January 14, 1918. See also the account on p. 193 of Ogilvie, “Training Errors of the A.E.F.,” which purports to be based on an otherwise unknown diary.

23 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of January 26, 1918. There is a photo from a slightly different angle taken by John Chadbourn Rorison, who was also at No. 2 T.S.; see Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 36.

24 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 13, 1917.

25 Cablegram 874-S.

26 See cablegrams 726-S and 955-R.

27 Cablegram 1303-R.

28 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.” There is no reason to doubt the date of this order for active duty, but Mudge’s inclusion in this particular list of active duty orders must have been an oversight, as it stipulates that each man on the list would be “on duty requiring him to participate regularly and frequently in aerial flights from the date indicated after his name.”

29 “Pat” is someone Milnor worked with at American Aviation H.Q., otherwise unidentified.

30 Milnor, diary entry for May 24, 1918.

31 Milnor, diary engry for May 27, 1918.

32 Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 299.

33 Milnonr, diary, May and June 1918, passim.

34 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for casual officers, Air Service, on Mauretania.

35 For his profession, see Ancestry.com, 1930 United States Federal Census, record for Dudley Mudge.