(Van Wert, Ohio, September 25, 1891 – Turnberry, Scotland, June 5, 1918).1

The family of Richard Brumback Reed’s mother can be traced back to Brumbachs who emigrated from Germany in the eighteenth century and settled in Virginia; it seems this branch of the family changed the spelling of the name to Brumback.2 One of Reed’s maternal great-grandfathers moved from Virginia to central Ohio, and Reed’s maternal grandfather, John Sanford Brumback, worked in various places in that state before settling in Van Wert, where he is particularly remembered for leaving funds in his will to establish a county library. In 1886 John Sanford Brumback’s daughter, Estella Brumback, married John Perry Reed, Jr. The latter, born in Pennsylvania, had moved to Van Wert in 1882; soon after his marriage he became cashier of the Van Wert National Bank.3 The couple had three children of whom Richard Brumback Reed was the oldest.

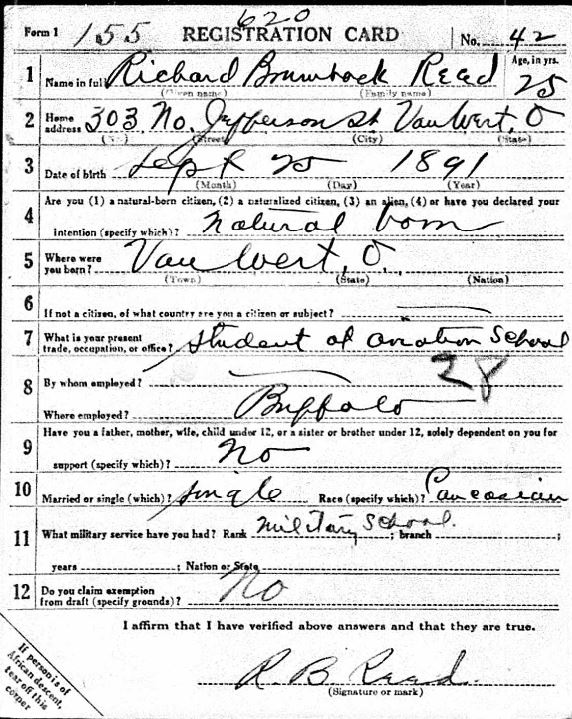

Reed attended the public schools in Van Wert; for the academic year 1908–1909 he is listed in the roster of cadets at the Culver Military Academy in Indiana.4 Reed then entered the University (now College) of Wooster in Wooster, Ohio, with the class of 1913; he was there an active member of the local chapter of the Sigma Chi fraternity.5 He transferred to Princeton (where an uncle had studied and a cousin was enrolled), graduating in 1916.6 Reed returned for a time to Van Wert to work in the bank where his father was cashier and then for at time for Standard Oil Company in Clarksburg, West Virginia.7 Soon after the U.S. entered the war Reed enrolled in the Curtiss Aviation School in Buffalo, graduating in June 1917.8 He went on from there to ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at Cornell University, from which he graduated September 1, 1917.9 He is reported to have been having a problem with his eyes, which might easily have put paid to his aviation career, but he evidently passed the final physical exam without it becoming an issue.10

Reed returned home and on September 9, 1917, married Gladys Marie Gilliland, daughter of another prominent Van Wert family, before proceeding to Mineola on Long Island.11 On September 17, 1917, as one of a 150-man strong detachment of cadets who had chosen or been chosen for flying training in Italy, Reed boarded the Carmania at a pier on the Hudson River on the west side of Manhattan. The Carmania sailed initially to Halifax where, after a brief stopover, she joined a convoy of ships for the Atlantic crossing. The men of the detachment travelled first class and had plenty of leisure, apart from daily Italian lessons conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them, and submarine watch duty towards the end of the voyage.

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. They soon made their peace with the change and in retrospect recognized the benefit of the R.F.C. training they received in England over the next few months. In the short term, classes at Oxford covered much of the same material that the men had had at ground school in the States, so that the cadets were not overburdened with homework or studying and had time to enjoy the amenities of Oxford college life and to explore the surrounding countryside.

When they arrived in Oxford, the cadets were housed in various colleges, but the next day were given more permanent rooms in Christ Church College and The Queen’s College. Reed was among the larger group at Christ Church; he shared a top floor room with Clark Brockway Nichol, Hilary Baker Rex, and Wilbur Carleton Suiter, all of whom had been in Reed’s ground school class at Cornell.11a

Reed initially understood that he would be at Oxford for six weeks, but it turned out to be four.12 Nevertheless, disappointment was in store for him and most of the cadets. On November 3, 1917, nearly all of the detachment, including Reed, left Oxford not for flying training, but to attend gunnery school at Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire. Fifty of these men left Grantham on November 19, 1917, for training squadrons, but Reed was again unlucky and remained at Grantham until early December to complete the second of two machine gun courses: they had been instructed initially on the Vickers and now moved on to the Lewis machine gun. The tedium was relieved somewhat when the cadets celebrated Thanksgiving in great style, with many of the men already at flying squadrons returning to Grantham for the festivities. The only other information I have found about Reed’s time at Grantham comes from the diary of a fellow detachment member, Fremont Cutler Foss, who, near the end of their time there, noted in his diary that “O. [R.] B. Reed got hell for violating censorship rules”—presumably in one of his letters home.13 There are many comments in letters written by detachment members about censorship and their uncertainty as to what could be included in letters; most, but clearly not all, erred on the side of caution.

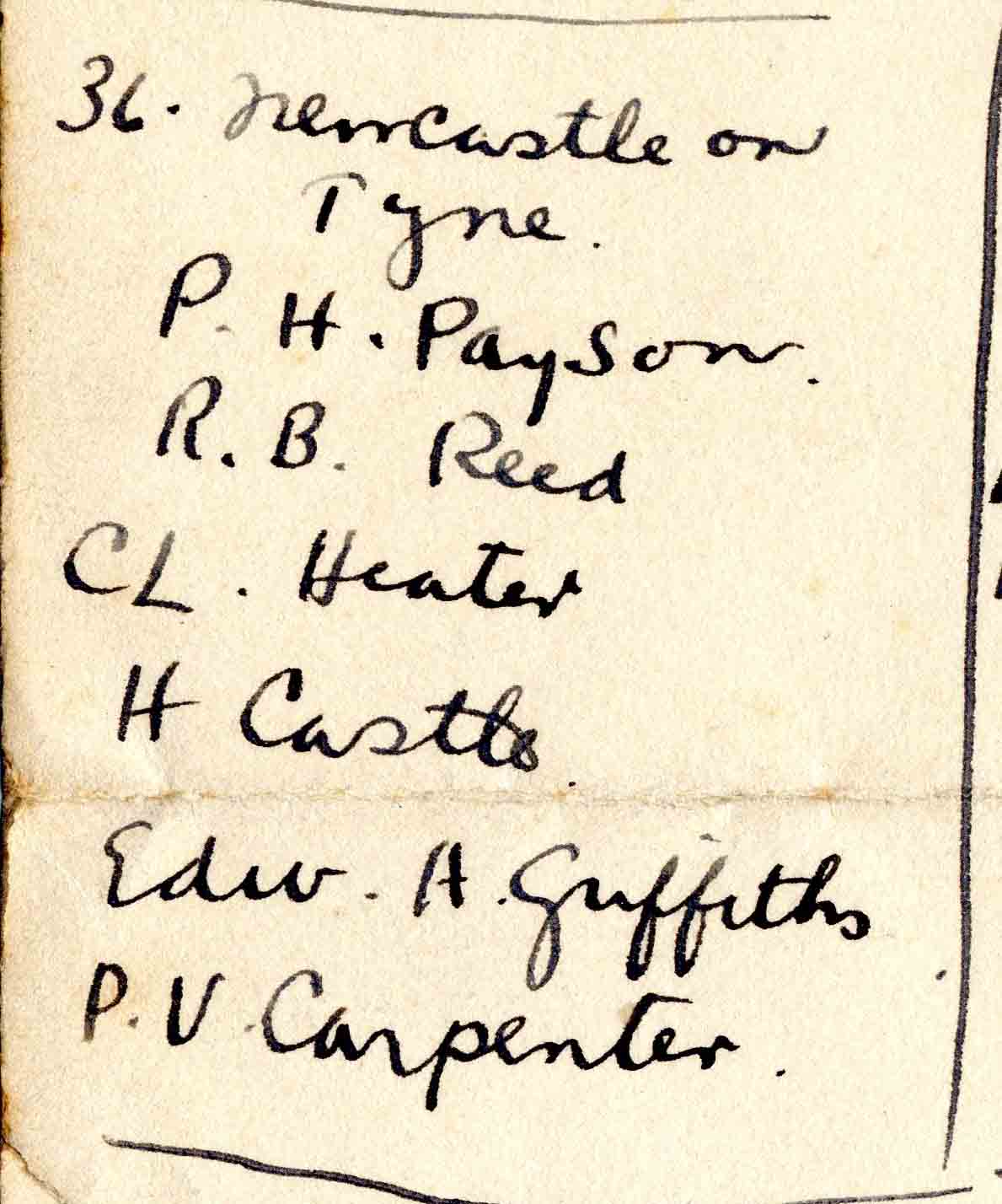

Finally, on December 3, 1917, the men still at Grantham were posted to squadrons, or, in the words of Reed’s Cornell ground school classmate Charles Louis Heater, to “any spot that could accommodate a few stray cadets.”14 Reed and Heater, along with Paul Vincent Carpenter, Harvard DeHart Castle, Edward Addison Griffiths, and Phillips Merrill Payson, were assigned to No. 36 Squadron, a home defense squadron flying F.E.2b’s and F.E.2d’s and based in and around Newcastle.15 Heater described this as a posting to “a night flying detachment of six or eight officers at a very small field near the North Sea coast entitled Hylton, near Sunderland.”16 While most of the men assigned to other squadrons actually began training, Reed, Heater, and their fellow detachment members found that at 36 “There was little flying activity . . . although we got a couple of short rides in the F.E.2b early British machines. . . . No instruction was given us.”17 This account is corroborated by Castle, who “said their crowd had had no instruction thus far; they were just marking time and fed up.”18 Again according to Heater, a welcome diversion came towards the end of the month when “we had a pass for London where on Christmas we were guests for dinner at the Royal Automobile Club, with a small party and the Marchioness of Tweesdale [sic], an amiable dowager, ‘doing her part’.”19

There is no direct documentation of Reed’s movements in the early part of 1918, but it is almost certain that his postings were the same as Heater’s, whose next assignment was to No. 6 Training Depot Station near Amesbury in Wiltshire. Many cadets were reassigned on January 26, 1918, and this is probably the date of Reed and Heater’s posting to No. 6 T.D.S.

Heater later recalled that “We were temporarily billeted in Amesbury and ate at the George Hotel, but not much later moved to tents at the field.”20 Heater, and presumably Reed, initially put in several hours of dual instruction on D.H.6s—about which Heater remarked: “Our first sight of the elementary D.H. 6 prompted a look to see who was holding the string, for they looked like box kites in a strong wind. However, they were very rugged and did their job well.”21 Heater, and presumably Reed, began flying solo in mid February and then moved on to the Armstrong Whitworth FK.8 and B.E.2c’s.22 It was apparent that Reed and Heater, like all the other men who had been with them at No. 36 Squadron, were being trained to fly the two-seater planes used for bombing and observation, rather than the single seater fighter planes: “Starting on the D.H. 6 til we soloed was a preliminary sign that we would not be trained for the more glamorous pursuit flying”—this is Heater again.23 Reed, writing home, suggests that this was a choice he had made: “After talking it over with the Major I have about decided to go over the lines with the two seater day-bombing machines.”24

By sometime in early March 1918 Reed had put in enough solo flying hours to qualify for a commission. The recommendation would have been forwarded to Pershing, who in turn forwarded it to Washington in a cable dated March 16, 1918.25 That army paperwork moved slowly was a source of frustration to the cadets. Action on Reed’s commission is a case in point: it was three weeks before Washington responded favorably to the recommendation.26

In the meantime, in a letter from the end of March 1918, Reed wrote about his further training: “The Aerial Navigation course teaches us to fly our machines entirely by instruments.” The earlier reprimand for censorship violation seems not to have made much of an impression, and the account in Reed’s letter of is unexpectedly detailed:

In this navigation course they teach one to plot a compass course making the necessary corrections for compass errors, unfavorable winds, speed of your machine and everything else that is necessary to keep one’s position in mind at all times. To graduate from this course the following examination must be successfully completed. The instructor gives a certain point on the map, informs the student of the speed and velocity of the wind at different altitudes up to twenty thousand feet. Then the student must plot his actual compass course and make a table in minutes of the exact location on the course his machine will occupy during the entire trip. Then the pilot is strapped in his seat and a canvas covering thrown over his cockpit so that he can not even see the wings of his machine or the earth. In other words his vision is limited to his “dashboard” or instrument board as it is called on an aeroplane. On this board are the following instruments: a compass illuminated by a small electric bulb, a propellor revolution indicator which tells him the theoretical speed of his machine and the running condition of his engine, a number of oil and gasoline gauges and their pressures, as well as numerous switches, etc., all necessary in keeping the engine at an even speed. Then there are “two way level bubbles” which show whether the machine is flying laterally and longitudinally level. There is also a suspended clock and a big illuminated map and chart board on which are the pilot’s course and incidental corrections. The trip generally covers a period of four hours and may be from 240 to 400 miles according to the speed of the machine. After the cover is put over the student’s head he does not again see the ground until at different points on the trip the instructor in the front seat pulls the cover off of his head and points to a spot on the ground and asks him to locate it precisely on the map. One cannot say “I think that it is Mannheim, or Berlin,” one must absolutely know. So you can realize that this military aviation is no longer a hit or miss luck game—it is being developed into a precise science and a fascinating science.27

Reed’s description of his training to fly by instrument resembles Vincent Paul Oatis’s account from his time at the No. 1 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping at Stonehenge, and it may be that Reed had been transferred there from No. 6 T.D.S.

The instructional period in Wiltshire was lengthy, and it was not until late May that Heater and Reed were assigned for the final stage of their training to the No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting and Gunnery, which, commanded by Lionel Wilmot Brabazon Rees, operated out of Turnberry and Ayr on the west coast of Scotland.28 Accommodations were “in the large resort hotel and were sumptuous!”29 The hotel was what in peacetime was the Turnberry golf course hotel, surely a welcome change after tents at Amesbury.

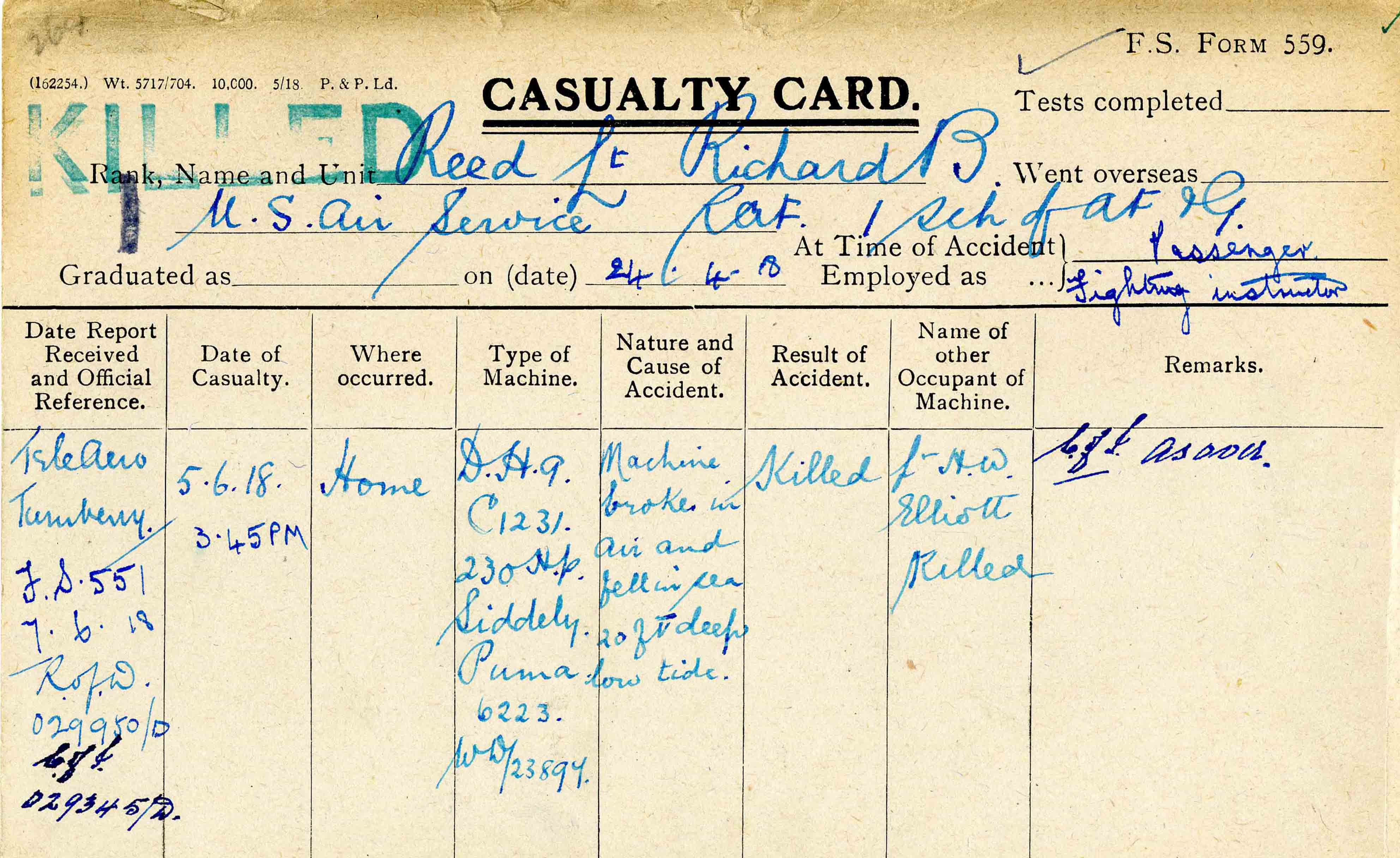

Reed spent his first week at Turnberry doing ground work and then on June 5, 1918, was taken up for his first flight there.30 The pilot of DH.9 C1231 was Hugh William Elliott, who had flown Bristol F.2 Fighters in France for over eight months, first with No. 48 and then with No. 11 Squadron R.A.F., before being posted to Turnberry as an instructor.31 “At about 3:45 p.m. . . . about one-fourth hour after leaving the aerodrome, and when at about two miles distance from it, in a Southwesterly direction, the machine, which was then at a height of about 500 feet above the sea at a point some 400 yards off shore, was seen to dive into the sea, parts of the fabric becoming detached in the course of descent and one of the planes being folded up.”32 This account is from a letter sent by Commandant Rees to Reed’s parents and reproduced in their local Van Wert paper in early July. Rees’s letter is unexpectedly lengthy and excruciatingly detailed, recounting attempts to locate the bodies of Elliott and Read, which “may be washed up at any part of the Firth of Clyde, or by the coast in the neighborhood of Stranraer, or even in the North of Ireland.” Rees reviews the evidence indicating that the men had not survived: “Elliott and Reed were undoubtedly in the machine when it took off, [and] two caps were recovered of which one bore Lieut Reed’s name . . . the officers were still missing after three days. . . .”

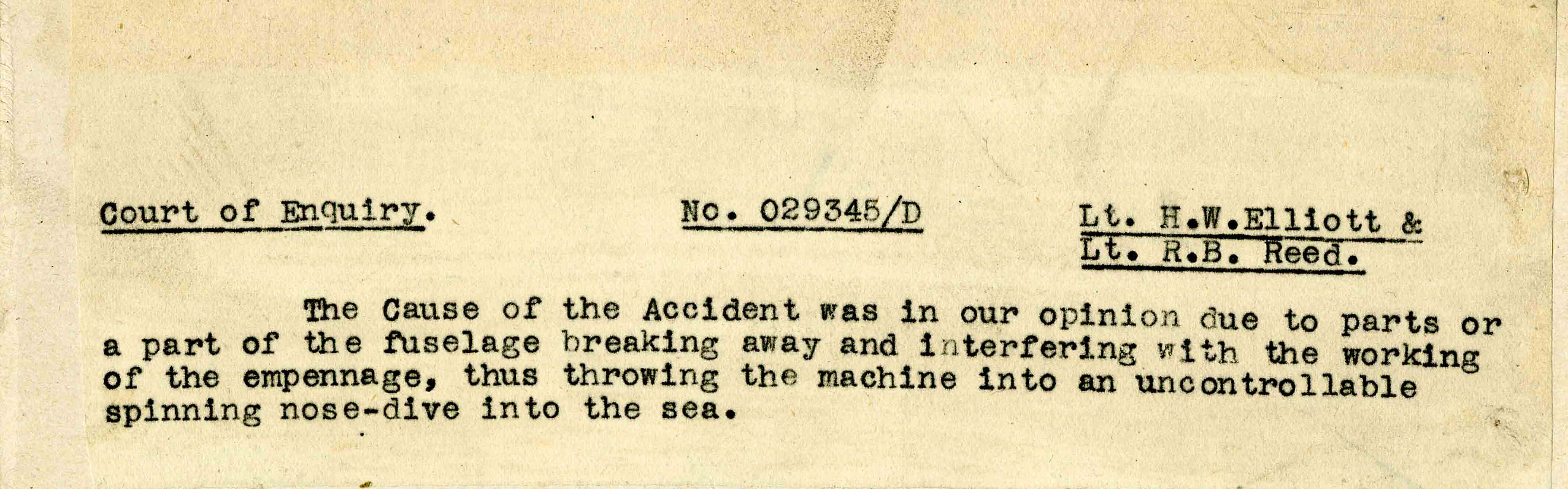

Regarding the cause of the fatal accident, Rees offers an account based on his understanding of the conclusions of the Court of Inquiry that was held three days after the accident: “the propeller of the machine exploded and disintegrated thus causing a sudden and overpowering strain to be put upon the engine from the violent increase in the number of revolutions per minute. This would unseat the engine from its bearers and partially wreck it whilst still aloft. This spin into which the machine got would throw a too strong strain upon the wing which was seen to fold, and there would then be no hope of a safe descent being effected.”33 This explanation seems to be at variance with the brief account of the Court of Inquiry’s conclusions attached to Reed’s and Elliott’s R.A.F. casualty cards: “The Cause of the Accident was in our opinion due to parts or a part of the fuselage breaking away and interfering with the working of the empennage, thus throwing the machine into an uncontrollable spinning nose-dive into the sea.”34

In either case, the crash is ascribed to catastrophic mechanical failure and not, as in many training accidents, pilot error.

In either case, the crash is ascribed to catastrophic mechanical failure and not, as in many training accidents, pilot error.

It fell to Heater to go through Reed’s personal belongings and to “act with the American Aviation Office, 35 Eaton Place, London, S.W.1, as representing the next-of-kin, in settling up the estate.”35 Heater wrote Reed’s family that

Dick was my best friend, we had been together constantly for nearly a year since leaving Cornell Aviation School and his going has been a big blow to me. . . . The week preceding Dick’s death he had been doing ground work . . . [at] Turnberry, Scotland, to which we had been recently transferred from Southern England. . . . At a strange aerodrome it is customary for a pupil to go up the first time with an experienced instructor in order to accustom him to the air conditions and the country about the Field. The instructor in this case was an Englishman named Elliottt, who had had ten months service in France and was considered a very good, steady flyer. The mishap was one that could not have been forseen [sic].36

Reed’s body was found on June 24, 1918, and a funeral was held for him that same day, when he was buried at Doune Cemetery in Girvan.37 As reported in the Van Wert newspaper, “Under the rule now being followed the bodies of American heroes are laid at rest in Europe. The family of Lieut. Reed expect to bring the body home at the close of the war.”38 His body now lies in the Reed family cemetery plot in Van Wert.

Reed’s papers, including letters home, were compiled into book form in 1967 by his brother and sister under the title The Story of One American’s Patriotism: Lieutenant Richard B. Reed and a copy deposited in the Brumback Library in Van Wert.39

mrsmcq February 20, 2023

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Reed’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Richard Brumbock [sic] Reed. For his date and place of death, see “Official Report.” The photo is the one published in “Our Nation’s Roll of Honor” in the New York Times’s Mid-Week Pictorial of July 11, 1918.

2 See Brumbaugh, Genealogy of the Brumbach Families, passim; p. 271, on changing the spelling of the name.

3 See “Van Wert Business Man Passes Away in Hospital in California.”

4 Culver Military Academy: Illustrated Catalogue 1909, p. 13.

5 See, for example, Harmon, ed., The Sigma Chi Fraternity Manual and Directory, p. 10.

6 Reed is also listed as a student in 1913 at Ohio Wesleyan; see Ohio Wesleyan University, Sixty-ninth Catalogue of Ohio Wesleyan University, pp. 143 and 209. This institution is not mentioned in biographical sketches in obituaries for Reed.

7 “The Great Sacrifice.”

8 See Reed’s draft registration, cited above, and “Solemn Service,” p. 4.

9 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

10 “Military Matters” (September 1, 1917).

11 “Society and Clubs.”

11a Rex, World War I Diary, entry for October 3, 1918; “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

12 “Military Matters” (October 6, 1917).

13 Foss, diary entry for December 1, 1917.

14 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 259.

15 “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers. On No. 36 Squadron, see See Philpott, Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 402, and Wikipedia, “RAF Usworth.”

16 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 259.

17 Ibid.

18 Castle’s remark is reported by Foss, in a diary entry for January 12, 1918.

19 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” pp. 259–60. The men were probably guests of the widowed Candida Louise, Marchioness of Tweeddale.

20 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 260.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid. (“slow, heavy, Armstrong-Whitworth early bombers, and B.E. 2cs”); Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 294, lists FK.8s and BE2b/e’s at No. 6 T.D.S.

23 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 260.

24 “His Last Letter,” p. 2. It is possible that the choice was not two-seater vs. pursuit, but day vs. night, or bombing vs. observation. It is, in any case, interesting that he had input into the decision rather than simply being assigned.

25 Cablegram 739-S.

26 Cablegram 1049-R, dated April 6, 1918.

27 “His Last Letter.” Minor spelling and punctuation errors have been corrected. On flying “head in bag,” see also Barber, Stonehenge Aerodrome and the Stonehenge Landscape, p. 19, as well as Vincent Paul Oatis’s letter of July 12, 1918.

28 The name was shortened at the end of May to No. 1 Fighting School; see Jefford, Observer and Navigators, p. 51.

29 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 260.

30 This according to Heater, excerpts from whose letters regarding Reed appear at the end of “Official Report.”

31 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Elliott.

32 “Official Report.”

33 “Official Report.” There is a similar account in the obituary of Reed on pp. 91–92 of “Among the Alumni.” Although reported as taken from an article in the August 9, 1918, Van Wert Daily Bulletin, only the account of the funeral appears in that newspaper article; the source of the account is thus uncertain.

34 See “Elliott, H.W. (Hugh William)” and “Reed, R.B. (Richard B.).”

35 “Official Report.”

36 Ibid.

37 “Body Found”; “Memory Extolled.”

38 “Body Found.”

39 “Patriotic Book is Memorial to Kin.” My efforts to gain access to the book have thus far (February 20, 2023) been unsuccessful.