(West River, Maryland, May 3, 1896 – west of Courtrai [Kortrijk], Belgium, July 29, 1918).1

Training in England ✯ France & No. 206 ✯ Afterwards ✯ Postscript

Galloway Grinnell Cheston was born into a prominent Maryland family. His father was Galloway Cheston, a landowner and farmer in West River in Anne Arundel County. He was a widower with four daughters when he married Henrietta Seymour McCulloch of Montreal, Canada, in 1893; Galloway Grinnell Cheston was born in 1896. Galloway Cheston died in 1905, and five years later Henrietta McCulloch Cheston married Theodoric Porter, retired commodore of the U.S. Navy and a widower with three daughters. Richly endowed with step-sisters, Galloway Grinnell Cheston was the only son in the family and his mother’s only child.2

He had a number of notable relatives. A great-uncle, (another) Galloway Cheston, was the first president of the board of trustees of The Johns Hopkins University.3 On his mother’s side, he was distantly related to Josiah Bushnell Grinnell, the founder of Grinnell College. Also on his mother’s side, a second cousin, Duncan William Grinnell-Milne, had been a pilot in No. 16 Squadron R.F.C. and would in 1918 join No. 56 Squadron R.A.F. and become its commanding officer.4 A first cousin on his mother’s side, Andrew Blyth McCulloch Bogle, had been killed leading an assault on Longueval early in the Battle of the Somme.5

Cheston was in the Signal Corps as early as 1911 when he was a pupil at St. John’s College Preparatory School in Annapolis (where yet another cousin, Daniel Murray Cheston, Jr., was briefly on the faculty as a professor of military science and tactics, and was, also briefly, commandant of the campus Signal Corps).6 Cheston was singled out as a “distinguished cadet” in the Signal Corps and received a medal as an expert rifleman as he continued as a student of mechanical engineering at St. John’s College at Annapolis.7 His name does not appear on college rosters after 1915, but he is posthumously listed as “class of 1916.”8 Cheston’s R.A.F. service record lists his “occupation in civilian life” from March through May 1917 as “farmer.”9 Perhaps at this time he was thinking of following the Cheston family tradition of gentleman farmers. A description of his uncle Robert Murray Cheston could apply to Galloway Grinnell Cheston as well: “descended from the area’s landed, tobacco-growing elite . . . part of the privileged planter class that dominated Chesapeake society and politics during the Colonial Period, and remained very influential throughout most of the 19th century.”10 However, a military career was evidently more appealing. Cheston joined the Reserve Officers Training Corps at Fort Myer, Virginia, on May 3, 1917.11 He evidently applied to and was accepted by the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and was sent to ground school at Cornell’s School of Military Aeronautics—where Daniel Murray Cheston, Jr., was now commandant—and graduated August 25, 1917.12

Training in England

Along with three quarters of his Cornell classmates, Cheston chose or was chosen to train in Italy and was thus among the 150 cadets of the “Italian” or “Second Oxford Detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York on September 18, 1917, bound initially for Halifax, where they joined a convoy that set off across the Atlantic on September 21, 1917. The men of the detachment travelled first class and had plenty of leisure, apart from Italian lessons given by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them, and, once they entered dangerous coastal waters, submarine watch duty.

When, after an uneventful crossing, the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the cadets found that they would in fact not continue on to Italy, but would remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. Initially disappointed by the change of plans, the men soon became reconciled to it. Their British instructors, unlike the ones in U.S., had had war flying experience, and this added considerable interest to the course work. Since the men had already covered much of the material, they did not have to study especially hard, and they enjoyed Oxford hospitality and explored the town and surrounding countryside.

The men were eager to start flying training, but more disappointment was in store for most of them at the end of four weeks at Oxford. The R.F.C. was able to accommodate twenty men from the detachment at No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford in early November, but the others, including Cheston, set out on November 3, 1917, for Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend a machine gun course at Harrowby Camp. As Cheston’s fellow Marylander, Parr Hooper, also sent to Grantham, remarked: “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”13

The men spent two weeks learning and practicing with the Vickers machine gun. In mid-November it was announced that there were openings for fifty men at squadrons, but Cheston was not among those posted, and thus, like the majority of the men, remained at Grantham and completed another two-week machine gun course, this time on the Lewis gun.

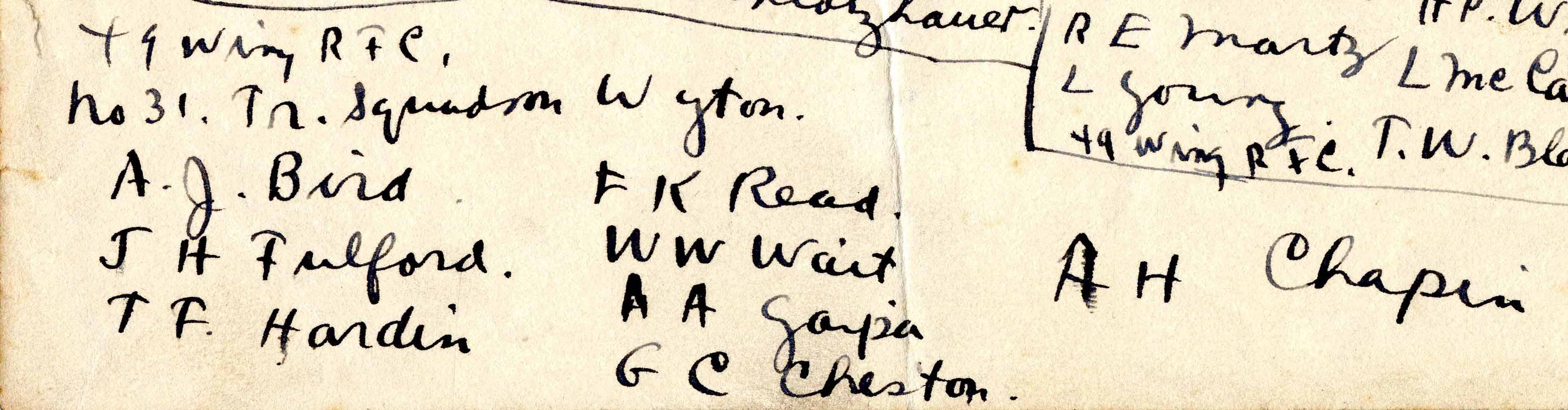

On December 3, 1917, the remaining cadets were finally posted to flying squadrons, and Cheston was one of eight assigned to No. 31 Training Squadron at Wyton, about fifteen miles northwest of Cambridge.14

At No. 31 T.S. Cheston would presumably have learned to fly initially on DH.6s—a two-seater aircraft designed for training—and then perhaps have gone on to fly dual on a Maurice Farman S.11; this is assuming his training resembled that of Francis Kinloch Read, also at Wyton, whose log book is extant. Cheston may, like Read, have completed his elementary training at No. 31 before Christmas, but this is surmise; there is very little documentation of his postings. His R.A.F. service record only notes planes he flew during training: DH.6, B.E.2c (an obsolete reconnaissance plane repurposed as a trainer), R.E.8 (used for reconnaissance and bombing), and DH.9 (a bomber, also used for reconnaissance).

By the latter part of February 1918 Cheston had completed enough flight training to be recommended for his commission, and Pershing’s cable forwarding the recommendation to Washington is dated February 28, 1918. The confirming cablegram announcing his appointment as a first lieutenant is dated March 11, 1918.15 One document indicates that when Cheston was placed on active duty on March 26, 1918, he was at Wyton.16 He may have been at No. 5 T.S. there, an advanced training squadron, but whether he had been posted away from Wyton and back, or had remained there throughout his training (which would have been exceptional) is not known.

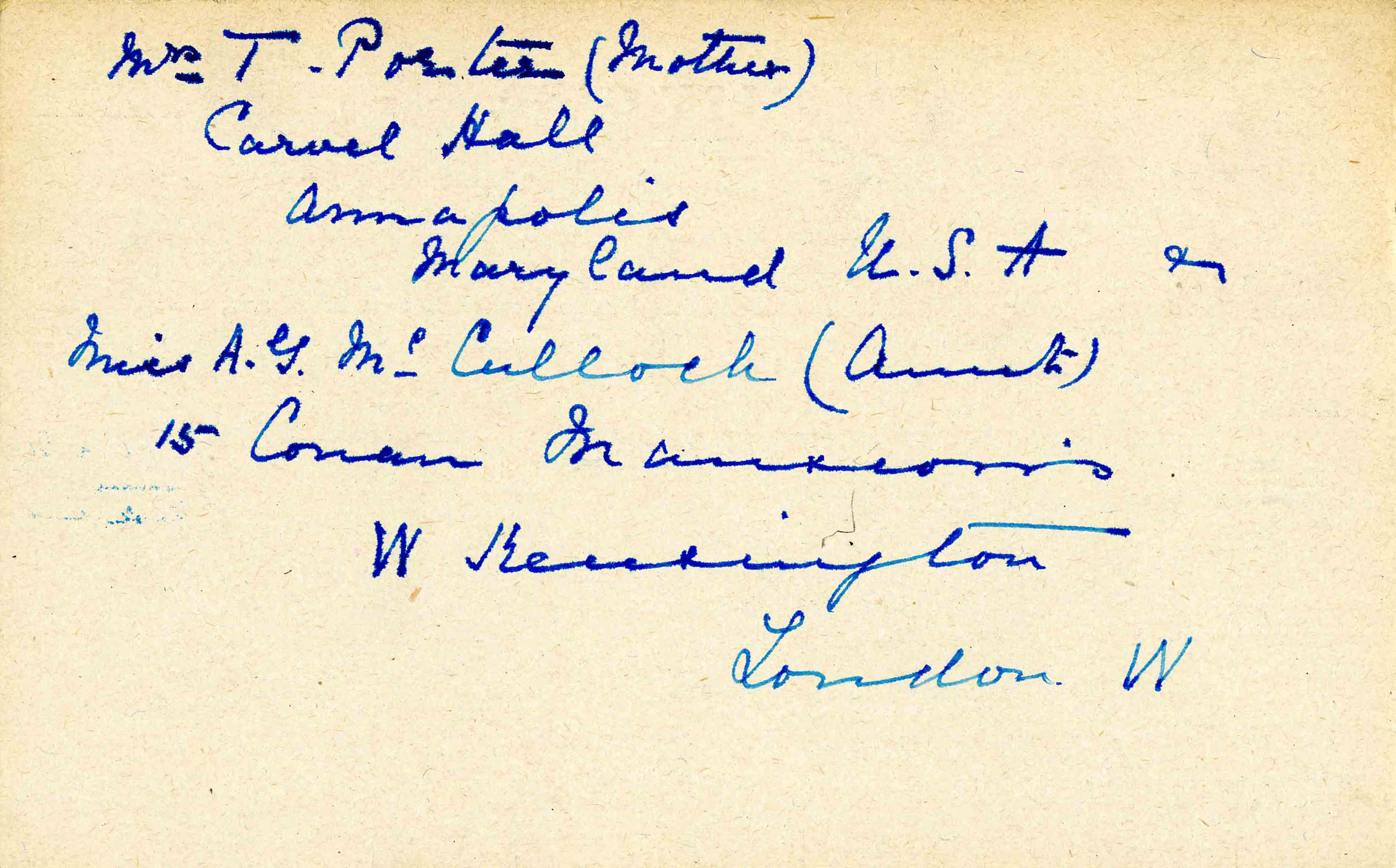

The records of other second Oxford detachment members show that they took the opportunity to travel within Great Britain during their training, and it is likely that Cheston did so also, particularly as he had family there. One of his mother’s sister’s, artist Alice Grinnell McCulloch, lived in London (she was designated as one of his emergency contacts), while the other, Helen Milne McCulloch Bogle (mother of Andrew, mentioned above), was in Edinburgh, where Cheston could have visited during graduation leave.

France and No. 206 Squadron R.A.F.

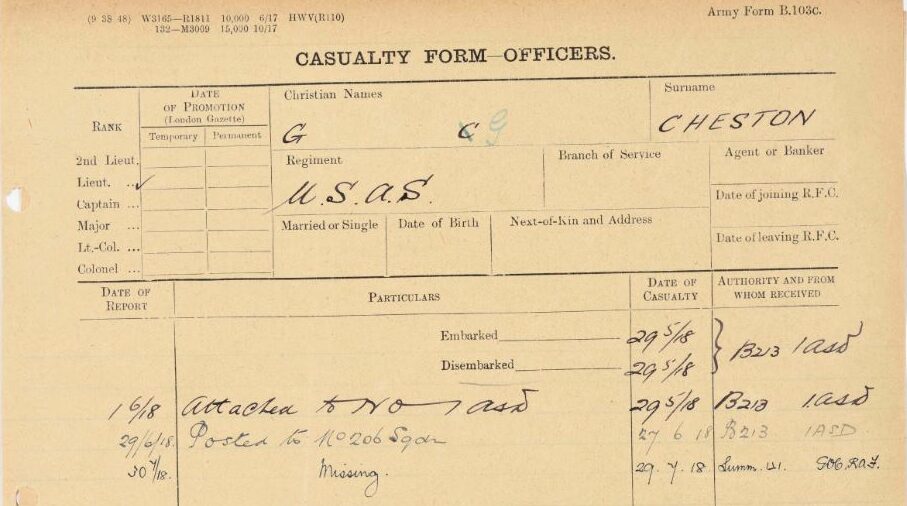

John Stephen Blanford, in his valuable account of his time at No. 206 Squadron, writes that Cheston joined 206, “the same day as I myself did,” i.e., May 29, 1918. However, Cheston’s casualty form indicates that on May 29, 1918, Cheston was posted to No. 1 Aeroplane Supply Depot at Marquise in France and was not assigned to 206 until June 27, 1918. He thus—I believe the casualty form is more likely to be accurate—apparently joined the squadron nearly a month after three other second Oxford detachment members: Harry Adam Schlotzhauer, John Warren Leach, and Hugh Douglas Stier.17

No. 206 Squadron, assigned to the R.A.F.’s 11th (Army) Wing, which supported the British Second Army, was stationed at Alquines, about twenty miles from the coast, east of Boulogne and south-southeast of Calais. The squadron had since February 1918 been flying DH.9s; they flew aerial reconnaissance and photography missions and carried out bombing raids.18 Blanford described 206’s remit during this period as follows:

“. . . our sector of operations, which was in fact the 2nd Army Front, ran from Houthulst Forest, 10 miles north of Ypres down as far as Nieppe Forest, 20 miles SW of that battered but unconquered old city [Ypres]–roughly 30 miles in all. The fierce fighting of the battle of the Lys (the final phase of the great German spring offensive) had petered out by the end of April and the 2nd Army Front had been stabilised. Since then the war on the ground had been passing through a relatively quiet period, with both sides resting and regrouping. In the air, however, there was still no lack of activity, and all 11 Wing squadrons were in the air whenever the weather permitted flying; . . .”19

There is little documentation directly related to Cheston’s time with No. 206. However, it is reasonable to assume that his experience resembled that of Schlotzhauer, whose time there is well documented by his log book. Like Schlotzhauer, Cheston was probably told to spend a week or so familiarizing himself with the squadron, the planes, and the geography. It may be that, as in Schlotzhauer’s case, a chronic shortage of manpower meant that Cheston, apparently assigned to B flight with Stier, went over the lines sooner rather than later. Weather would have cut into his gaining experience flying at the front: Blanford notes that there were twelve days in July when flying was not feasible, and there is a five day, presumably weather-related, gap in Schlotzhauer’s log book between a raid on Roulers on July 7 and the next on July 13, 1918. Around the time flying resumed in the middle of July “there was a marked increase in enemy fighter activity . . . the famous ‘Circus’, originally led by von Richthofen and now by Hermann Goering, was paying our sector a visit.”20

During the latter part of July, Schlotzhauer flew line patrols and long reconnaissance missions and took part in several bomb raids on Courtrai. Schlotzhauer and Cheston were in different flights, but likely flew on similar missions or, at times, on the same mission. Leach described how “We go over the lines in formations of five to twelve machines, and do our work,” i.e., sometimes one flight at a time, sometimes two. “We fly from 15,000 to 20,000 feet now—four miles high. We have to take oxygen with us, for we are up from two to four hours at a time.”21

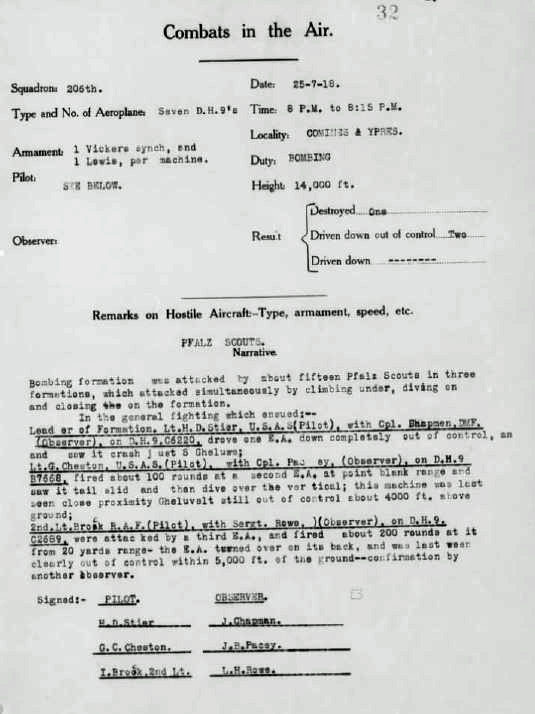

For most of July Schlotzhauer does not record any combats, and a perusal of this period in Henshaw’s The Sky Their Battlefield II shows 206 flying largely unscathed. This changed beginning July 25, 1918. That evening Cheston and Stier, presumably as part of B flight, set out on a bombing mission—I find no record of their objective, but it may well once again have been Courtrai. Flying at 14,000 feet in the vicinity of Ypres and Comines—probably on their return journey—the DH.9s “were attacked by about fifteen Pfalz Scouts in three formations, which attacked simultaneously by climbing under, diving on and closing on the formation.” Stier, who was leading the flight, and his observer James Chapman “drove one E.A. down completely out of control, and saw it crash just s[outh of] Geluwe.”22 Cheston, flying DH.9 B7668 with Joseph Woodley Pacey as his observer, “fired about 100 rounds at a second E.A. at point blank range and saw it tail slid [sic] and then dive over the vertical; this machine was last seen close proximity Gheluvelt still out of control about 4000 ft. above ground.”23 A third Pfalz was sent down out of control by Frederick Albert Brock and his observer, Leslie Holman Rowe.24

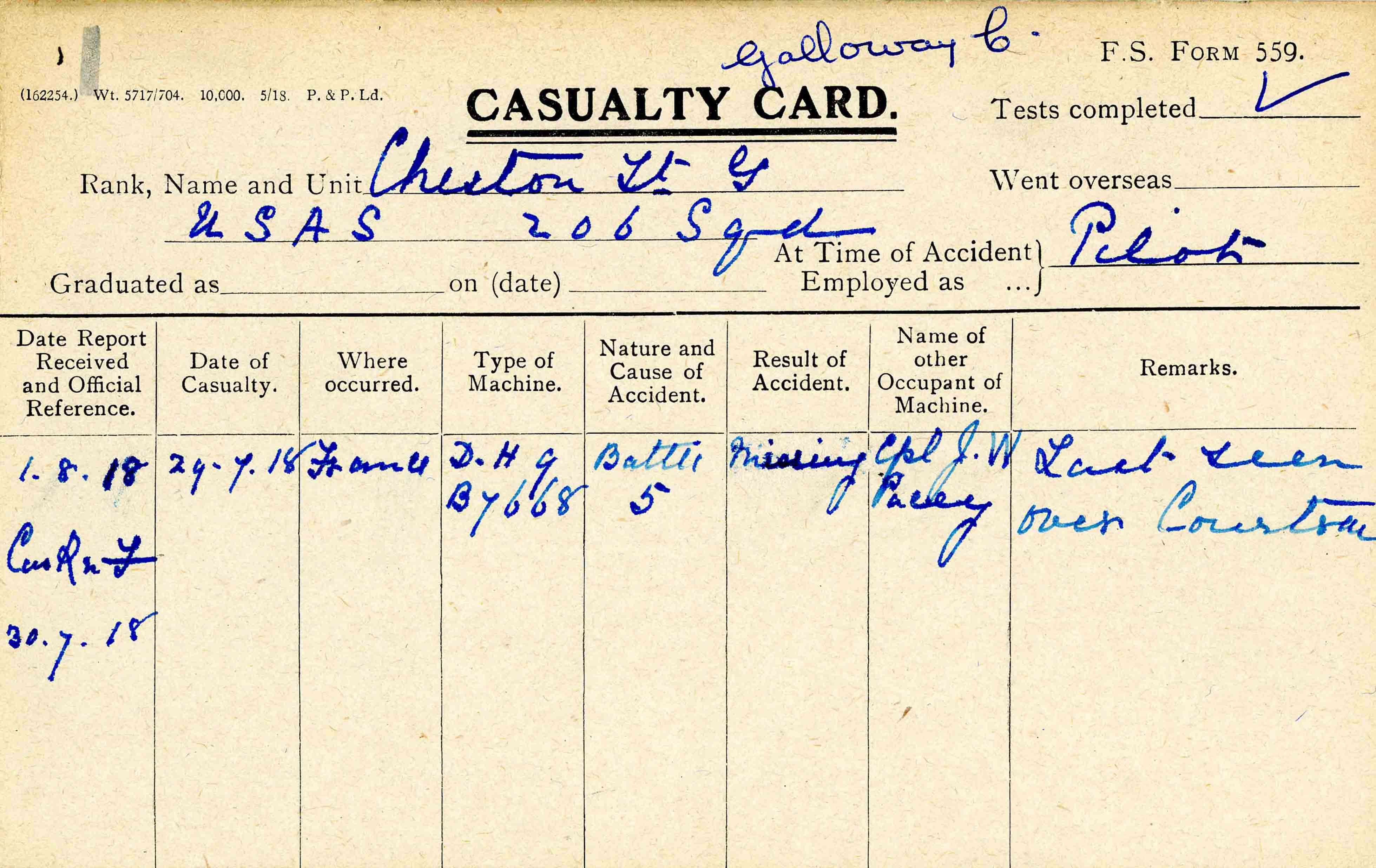

Four days later, on July 29, 1918, pilots from No. 206 Squadron flew two bombing missions over Courtrai. Blanford describes them (although because he was himself on a reconnaissance mission, his knowledge is second hand):

During the first raid, some Pfalz fighters attacked the 206 formation on their way home, two being shot down. . . . During the second raid, in the late afternoon, a much hotter fight took place, the eight aircraft of our formation being attacked by a far larger number of Pfalz—Schlotzhauer stopped counting at 20!—while our chaps were about to drop their bombs. In the ensuing combat, 206 shot down four Pfalz, a notable feat achieved at some cost. Schlotzhauer and [Horace Walter] Williams were badly shot up. . . . Williams was hit in the left arm. . . . Our other casualties were Lt Cheston, US Army and his observer, who were both killed; and 2 Lts [John Frederick Spencer] Percival and [Frederick James] Paget.25

An unnamed comrade is recorded as having given the following account:

The day that ‘Chess’ did not return our squadron was very hard hit. They set out to bomb Courtrai railroad station and yards, which at that time were at least fifteen miles beyond the front lines. ‘Chess’ had been having a little engine trouble for two or three days preceding, but it was not serious enough to prevent his crossing the lines. On this raid about 4 P.M. they had to run through a pretty stiff ‘archie’ barrage, but as they approached the target at about fourteen thousand feet altitude the barrage died away. They dropped their bombs, and as the formation turned it was noticed that ‘Chess’ was slightly lower than he should have been, but not seriously out of his position in the formation. Just as they were turning they were attacked by about three times their number of Huns, and from there on it was a running fight back to the lines. Several pilots and observers noticed that one machine seemed to be losing altitude, as if the engine was not giving its full power, and it was assumed that the pilot was depressing the nose of his machine in order to keep up his speed and not fall behind the others, thus keeping under the formation for protection. Each machine was engaged in desperate fighting all this time and making for the lines, so that no one really had an opportunity to look about him to see how the others were faring. However, one pilot states that he saw ‘Chess’’ machine, which was getting lower and lower, though still under control, and the last anyone saw it was surrounded by five or six Huns, and was manoeuvering desperately to get away or beat them, but obviously the odds were too great.26

Afterwards

It was reported—by what authority is not stated—in the Baltimore Sun on August 17, 1918, that Cheston was a prisoner. Cheston’s mother learned officially by August 20, 1918, that he was missing in action, and his name appeared among the missing in action in the official casualty list of August 23, 1918.27 Strenuous efforts were made to find out what had happened to Cheston, his mother making a public appeal in the spring of 1919.28 Sallie Maxwell Bennett, mother of Louis Bennett, who had been shot down while flying with No. 40 Squadron R.A.F., assisted in the search when she was in Europe in the summer of 1919 trying to locate the remains of her own son.29 She apparently had a photo of Cheston on the back of which were noted, possibly by Henrietta McCulloch Cheston Porter, contact information, some of Cheston’s identifying physical characteristics, and details of Cheston’s plane and last flight, including the information that he was “last seen over Courtrai.”30 This last would accord with a notation on the relevant casualty card, and had perhaps been relayed to Cheston’s mother by 206 Squadron C.O. Colin Temple MacLaren.

Official efforts to determine Cheston’s fate involved no less a person than the Chief of U.S. Army Air Service Mason Mathews Patrick, who in late January 1919 wrote to Charles Campbell Pierce, head of the American Graves Registration Services, asking whether the G.R.S. had any record of Cheston’s interment.31 Some of the information Patrick forwarded to Pierce was accurate, but he was under the impression that No. 206 Squadron was part of the Independent Air Force “near Nancy” and that “Cheston was shot down while on a mission toward the Rhine.” Pierce, apparently relying on a garbled telephone message, wrote back to Patrick that “D. P. Cheston . . . was reported . . . as missing in action July 21st.”32 Errors and miscommunications, perhaps inevitable in such chaotic times, continued and multiplied, and hampered the investigation into Cheston’s fate. It was unfortunate that, when Bennett drafted a note with information for Pierce, she wrote that Cheston’s plane had been “last seen going down slowly . . . in the direction of Courtrai” [my emphasis].33

A search was conducted in June 1919 by Herbert Eugene Felter of the G.R.S. “in the vicinity of Ypres,” without result.34 But just as he completed his report Felter was redirected, apparently because of the information supplied by Bennett to Pierce, to search in the vicinity of Courtrai.35 Another false lead came from a report made by the otherwise unidentified William Mordly, who told of a priest’s story of a plane falling over Courtrai and injuring a girl on July 29, 1918: “It seems to me probable that Lieutenant Cheston must have been one of the occupants of this plane.”36 After a long investigation, it was determined that a DH.9 had indeed fallen on Courtrai, but the date was October 14, 1918, and the pilot H[arold] W[illiam] Bingham.37

The American G.R.S. continued to focus on Courtrai until the autumn of 1920, when Guy Ichabod Rowe—whose interview of the injured girl put paid to Mordly’s surmise—concluded that “Cheston did not fall in the vicinity of Courtrai on July 29, 1918.”38 Not long after this, Schlotzhauer was apparently debriefed, and, finally, in early 1921, American authorities in general realized that Cheston’s plane must have crashed a few miles west of Courtrai in the vicinity of Becelaere.39

British authorities who knew of the casualty report for DH.9 B7668 were aware that the plane had last been seen not over Courtrai, but “West of Menin, (Roulers Road).”40 During the summer of 1919, the R.A.F. searched for the bodies of fallen airmen, including that of Cheston, “in this area in which he is thought to have been buried, namely West of the Kruissecke Wevicq Road.” The search in this particular area may have been prompted by awareness of a claim made by Jagdstaffel 16’s Friedrich Röth for a Bristol Fighter [sic] over Gheluvelt at 7:35 p.m.41 However, during this search “no graves of airmen were found,” and this negative information was communicated by the Imperial War Graves Commission to the G.R.S. in late 1920.42 The paper trail shows that American efforts to locate Cheston’s body continued well into 1921.

In late July 1919 Cheston’s mother had been notified that her only child had been declared killed in action—this was based not on new information but the lapse of time.43 In 1925 a boyhood friend of Cheston raised hopes that Cheston’s plane and body had been found, but it was quickly determined that this was incorrect.44

In the early 1930s Cheston’s mother planned to take part in one of the Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimages to Europe which would allow her to visit in particular the Flanders Field American Cemetery and Memorial in Waregem, Belgium, where Cheston’s name had been inscribed in the memorial chapel “together with the names of other veterans who lost their lives in this section but whose remains have not been located.”45 Sadly, age and ill health ultimately kept her from making this journey.46

Cheston’s observer, Pacey, had joined the Royal Navy in September of 1916 and had been transferred to the R.A.F. in March of 1918.47 His brother, James Wabe Pacey, a private in the East Lancashire Regiment, was killed on July 12, 1918.48 Joseph Woodley Pacey, whose body, like Cheston’s, was not located, is memorialized at the Arras Flying Services Memorial.49

Postscript

In September 1919 two bodies were found in isolated field graves about halfway between Terhand and Geluwe; they were not identified other than as being an unknown officer and an unknown soldier, both of the R.A.F. They were reinterred in Duhallow Cemetery near Ypres. Researcher Luc Degrande has made a strong case that these are the bodies of Cheston and Pacey and in 2019 submitted a report to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission; it is no. 621 of the C.W.G.C. open case files.

mrsmcq May 31, 2017; revised February 20, 2019, to reflect Cheston’s casualty form; revised September 2023 to reflect Schlotzhauer’s log book, Sallie Bennett’s papers, and Cheston’s burial file.

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Cheston’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Galloway G Cheston. The photo is a detail from a group photo of his Cornell ground school class.

2 Information on Cheston’s family is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com. Thomas, The Thomas Book, p. 246, indicates that Galloway Cheston and his first wife had two sons who died young—before 1896, when The Thomas Book was published.

3 “Historical Note.”

4 Wikipedia, “Duncan Grinnell-Milne.”

5 “Pte. G. R. Barber Dead of Wounds.”

6 St. John’s College, Catalogue of St. John’s College Annapolis Maryland for the Academic Year, 1910–1911 and Prospectus 1911–1912, pp. 55 and 84. On Daniel Murray Cheston, Jr., see St. John’s College, Circular of St. John’s College Annapolis Maryland for the Academic Year, 1912–1913 and Prospectus 1913–1914, pp. 14, 65, and 66.

7 St. John’s College, Circular of St. John’s College Annapolis Maryland for the Academic Year, 1912–1913 and Prospectus 1913–1914, p. 18, lists Cheston as a freshman studying mechanical engineering. St. John’s College, Catalogue of St. John’s College Annapolis Maryland for the Academic Year, 1914–1915 and Prospectus, 1915–1916, p. 57, lists him as a distinguished cadet; the medal is noted on p. 58.

8 Alumni Association of St. John’s College, Register of the Alumni (Second Edition), p. [6].

9 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Galloway Grinnell Cheston.

10 “Richland,” section 8, p. 1.

11 See “Galloway Grinnell Cheston, First Lieutenant. . . ,” p. 325. His (undated) draft card also puts him at Fort Myer. The entry for Cheston in Maryland War Records Commission, Maryland in the World War, 1917-1919: Military and Naval Service Records reads in part: “ERC 6/25/17 pvt 1c.”

12 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].” On Commandant Cheston, see Wm. N. Barnard, “The U. S. Army School of Military Aeronautics at Cornell University,” p. 65.

13 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

13a The photo is cropped from Portrait—Lt. Galloway Cheston, in box 9, folder 16, of the Sallie Bennett Papers regarding World War I Flying Ace Louis Bennett, Jr. (A&M 1590) at West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

14 Foss, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” (in Foss, Papers).

15 Cablegram 660-S; cablegram 900-R, p. 3 (this is an addendum to a cablegram dated March 9, 1918),

16 Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

17 For Blanford’s account of the arrival of Cheston and the other Americans, see his “Sans Escort,” pt. 2, p. 21. For Cheston’s casualty form, see “Lieut. G. G. Cheston.” The dates provided by the other men’s casualty forms also differ from Blanford’s account; unfortunately, their R.AF. service records, where they exist, provide no evidence one way or the other, and the 206 Squadron record book appears to be no longer extant. It seems likely that Blanford, writing nearly sixty years after the event, was not recollecting the actual day, but rather working from a document similar to that which served as Warren Munsell’s source for his “Air Service History” list of Americans who served with the R.A.F., i.e., one that conflated assignment to the R.A.F. and posting to a particular squadron.

18 On 206’s location and planes flown, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 433.

19 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 147.

20 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 150.

21 “Lieut. Warren Leach, Tuscaloasa [sic] Birdman, Tells in Letter of Air Fighting.”

22 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 151, has perhaps been misled by the wording of the relevant R.A.F. communiqué and gives the date of this combat as July 22, 1918; cf. “‘With Fondest Love, Trev.’,” p. 143, who cites the communiqué.

23 “Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F.,” p. 32. Geluwe and Gheluvelt (Geluveld) are about eight and five miles east southeast of Ypres respectively.

24 The combat report is “signed” (names are typed) by “I. Brock,” but this is almost certainly Frederick Albert Brock flying with observer Rowe. Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 228 (36), unaccountably indicates that Stier and Cheston shared credit for the destroyed Pfalz. Cheston and Pacey’s “out of control” would presumably not have appeared in the relevant R.A.F. communiqué, as, by this time, the “sheer volume” of such claims made their inclusion impracticable; see Shores, Franks, and Guest, Above the Trenches, p. 6.

25 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 151. Blanford is mistaken in recalling that pilot John Frederick Spencer Percival and his observer Frederick James Paget were both wounded on this raid. They did take part and were credited with a Pfalz, but it was on August 1, 1918, that Paget, again flying with Percival, was mortally wounded. Percival sustained injuries on August 7, 1918, and died in early 1919; see the relevant entries in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II.

26 “Galloway Grinnell Cheston, First Lieutenant . . . ,” p. 326.

27 “Aviator Made Prisoner”; “Informed Officially that Son is ‘Missing’.” The casualty list of August 23, 1918, was published by various newspapers that day and the next; see, for example, “260 Names in Lists Sent out by Pershing.”

28 “Mother Still Seeks News of Aviation Son.”

29 See memo from Charles C. Pierce to Bennett dated June 18, 1919 (item 103 in Cheston, World War One Burial File).

30 The photo and note are among the Sallie Bennett Papers regarding World War I Flying Ace Louis Bennett, Jr. at the West Virginia and Regional History Center at West Virginia University. There are two letters handwritten by Cheston’s mother in Cheston’s World War One Burial File (items 9 and 12), both written when she was old and infirm. There are enough similarities to the handwriting on the back of the photo to justify tentatively identifying the latter as written by her.

31 Cheston, World War One Burial File, item 121.

32 Cheston, World War One Burial File, items 117 and 119.

33 Cheston, World War One Burial File, items 96–97. The note is not signed, but comparison with documents known to be in Sallie Bennett’s hand establishes that she was the author.

34 See his memorandum to F[rederick] S[chmidt] Roumage (item 80 in Cheston, World War One Burial File).

35 See items 101 and 102 in Cheston, World War One Burial File.

36 Cheston, World War One Burial File, item 76 (same as item 94).

37 Cheston, World War One Burial File, items 61–64 (same as 84–86).

38 Ibid., item 62.

39 Cheston, World War One Burial File, item 58.

40 See the relevant report in The National Archives (United Kingdom), Reports on aeroplane and personnel casualties, 21 July 1918 – 31 July 1918. 206 Squadron C.O. MacLaren was surely aware of this; if he was the source of the information that Cheston’s plane had last been seen “over Courtrai,” he was perhaps making a geographic generalization that would be comprehensible to those not familiar with the area.

41 See Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II.

42 This is from a letter dated November 17, 1920, signed by R. C. Engelback [sic; sc. Rupert Charles Engelbach?] for the Imperial War Graves Commission and addressed to the American G.R.S.; it is item 67 in Cheston, World War I Burial File.

43 “Lieut. G. G. Cheston Killed in Action, Mother Learns.”

44 “Flyers’ Bodies in France May Solve Mystery”; “Neither Skeleton Thought Cheston’s.”

45 Cheston, World War One Burial File, item 6.

46 See the extensive correspondence concerning the pilgrimage in the early part of Cheston, World War One Burial File.

47 Ancestry.com, UK, Royal Navy Registers of Seamen’s Services, 1900-1928, record for Joseph Woodley Pacey.

48 Ancestry.com, Military-Genealogy.com, comp. UK, Soldiers Died in the Great War, 1914-1919, record for James Wabe Pacey.

49 See “Pacey, Joseph Woodley.”