(Philadelphia, March 4, 1894 – Los Angeles, November 26, 1952).1

Armstrong’s father was a house and sign painter in Philadelphia, and “Army” went into the same business.2 When he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, he indicated he was a painting and decorating contractor working temporarily for the U.S. government; he was also at that time in the R.O.T.C. at Fort Niagara, New York. I have not found a record of college attendance. He went to ground school at Cornell, graduating August 25, 1917.3

Along with three quarters of his Cornell ground school classmates, Armstrong was selected for training in Italy and was thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania, departing New York on September 18, 1917. After a stop in Halifax, they had an uneventful crossing and docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917.

There they learned, to their initial considerable dismay, that they were not to go to Italy after all, but to train with the R.F.C. in England. They attended ground school (again) at Oxford.

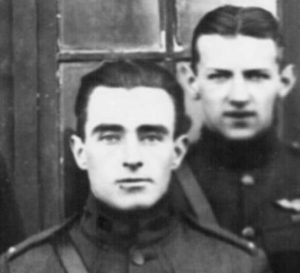

Armstrong then departed with most of the detachment for machine gun school at Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire, on November 3, 1917. About two weeks later, it was determined that fifty of these men could go to training squadrons, and on November 19, 1917, Armstrong (along with Norman Kenneth Berry, Murton Llewellyn Campbell, Leonard Joseph Desson, Charles William Harold Douglass, Weston Whitney Goodnow, Bradley Cleaver Lawton, Clair Rutherford Oberst, Earl William Sweeney, and George Herbert Zellers) set off for Doncaster in south Yorkshire where Nos. 41 and 49 Reserve [Training] Squadrons were located; Armstrong, Berry, Douglass, Goodnow, and Zellers went to No. 41.4 A postcard photo of a man in flying suit and helmet identified as “Wm. J. Armstrong” and taken by a photographer in Doncaster presumably comes from this period.5 There is no R.A.F. service record for Armstrong, and the documentation for his further training is limited.

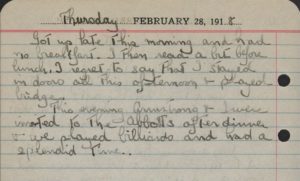

A diary entry by Elliott White Springs from February 21, 1918, about a party in Girvan suggests Armstrong was in Scotland at this time, as do entries for February 27 and 28, 1918, in the diary kept by Gustav Hermann Kissel.6

By early March 1918 Armstrong had completed enough flying hours to qualify for his commission, and Pershing forwarded the recommendation on March 18, 1918.7 The cablegram confirming his appointment as a first lieutenant is dated March 26, 1918.8

On about May 24, 1918, Armstrong, along with fellow second Oxford detachment member Frank Aloysius Dixon, was assigned to No. 209 Squadron R.A.F., a Camel squadron stationed at Bertangles, a few miles north of Amiens—which city, as a result of the first phase of the German Spring Offensive, was now only about fifteen miles from the front.9 Dixon recalled that “the German advance lines were then too near for comfort.”9a Desson was already at 209, and Bradley Cleaver Lawton arrived around the same time.9b Other detachment members were or would soon be at Nos. 48, 65, and 84 Squadrons, R.A.F., which were also flying out of Bertangles.

On May 25 and 27, 1918, Armstrong made the first two of only three practice flights.9c The next day he was sent up in fine weather to a bone-chilling 18,000 feet to serve as an aerial sentry in the area between the aerodrome and Amiens; he reported no enemy aircraft observed.9d After some practice firing at a ground target on June 1, 1918, he again served as an aerial sentry, this time at 13,000 feet. On June 2, 1918, he was back at 18,000 feet, flying Camel D3368, which would be the plane he flew the remainder of his time at 209. He also, on June 2, 1918, went over to 2 A.I. at Saint André au Bois and flew newly built Camel D9593 back to Bertangles—which helped keep the number of functioning planes at the squadron at about 19.9e

The morning of June 3, 1918, Armstrong was in the second team of three planes flying a “Special Mission W.E.A.”; the other pilots in the formation were Mark Adamson Harker and Hubert Mason.9f 209 Squadron pilot Cedric Nevill Jones described missions of this type as “dashes after Hun two-seat artillery observation machines. Three of our aircraft were always on standby for these jobs. . . a Klaxon was sounded . . . and the standby pilots raced to their machines [and were] off the ground in two minutes after calling at the office for the chit with the location of the enemy aircraft. . . . It was a very unrewarding business because the Hun invariably saw you coming at a very great distance and were away like lightning. . . .” 9g Armstrong’s team evidently had better than usual luck; upon return at 11:39 a.m., they reported “One two-seater driven down near Cerisy emitting clouds of white smoke, at 10:45” (Cerisy was just about four miles inside German-held territory).

Two days later, in the evening, Armstrong took part in his first high offensive patrol, led by B flight commander Oliver Colin Le Boutillier; Lawton was the third pilot. They reported “1 E.A observed near Quesnal at 7.20. pm going East.” “Quesnal” is presumably Le Quesnel, about twenty miles from Bertangles and about ten miles inside the German lines at this time. Armstrong flew with Le Boutillier and Lawton again the next day on another W.E.A. near Marcelcave, and again on June 7, 1918, when they “Attacked one L.V.G. over Bois de Mametz and drove it down to the ground at 8.25 a.m.”—the plane was presumably a two-seat reconnaissance plane built by the Luftverkehrsgesellschaft, driven down about four miles east of Albert, just inside the German lines.

On June 9, 1918, the German army opened the fourth of their 1918 offensives on the Western Front, in an operation variously known as Gneisenau, the Battle of the Matz, and Montdidier-Noyon. No. 209 Squadron sent an unusually large formation of eleven planes to assist in the defense. Armstrong, along with Lawton and Desson, was one of the pilots on this high offensive patrol. The planes—again unusually—carried bombs and dropped them between Boussicourt and Davenescourt and also east of Montdidier. Three pilots had to turn back early, but the others, including Armstrong, were in the air for two hours.

Armstrong flew again on June 11 and 12, 1918. On the 11th, two of the approximately twenty-three pilots in the squadron fell ill, and the number of sick pilots increased daily until on the 17th thirteen of them were sick, most of them in hospital. The squadron record book notes no flights by Armstrong from June 13 through June 19, 1918, and it is likely that he was among those who succumbed to influenza.

By June 20, 1918, nearly all the men, Armstrong included, had recovered. That day he, along with Lawton, took part in a six-plane strong high offensive patrol. Once again they carried bombs, which were dropped on Proyart at 6 p.m.; at the same time, an enemy Pfalz was encountered and driven down.

Armstrong’s final two missions with No. 209 Squadron were three-plane W.E.A.’s on June 21 and 23, 1918; on both flights, Armstrong’s fellow pilots were John Kenneth Summers and Lionel Frank Lomas, and both flights took them to the vicinity of Martinpuich, twenty miles east northeast of Bertangles and about five miles over the lines. On the 23rd they “Attacked two 2-seaters near Martinpuich at 7.10 a.m. One left in steep spiral at 100 feet, the second machine retired East.” A combat report was filed, and Summers and Armstrong shared credit for an out of control plane. 9h Armstrong probably knew or suspected at this time that he would soon be transferred to an American squadron, and it presumably felt good to go out with a victory to his credit.

On June 26, 1918, Armstrong, along with fellow members of the second Oxford detachment Desson, Dixon, and Lawton, was assigned to the 17th Aero Squadron, stationed at Petite Synthe near Dunkirk, joining a number of second Oxford men already there.10 The 17th flew Camels and, along with the 148th, was American in personnel, but stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until late in the war when they were moved south to the American Front. Armstrong was in C flight, under flight commander Hamilton and deputy commander Frost; his fellow C flight member Robert Miles Todd took a photo in early July of Armstrong, Hamilton, Lawton, and others at Petite Synthe.11 After about three weeks of getting to know their equipment and their territory while working on formation flying (and crossing the lines, despite R.A.F. regulations), the 17th flew their first offensive patrol on July 15, 1918; they began escorting DH.9 bombers into German occupied territory on July 20, 1918.12

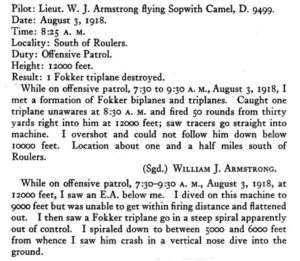

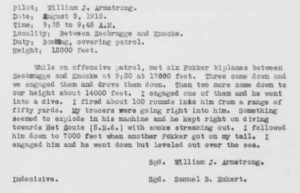

On August 3, 1918, during a morning offensive patrol south of Roulers, Armstrong shot down a Fokker triplane; a few days later (August 8, 1918), as part of a bomber escort on a raid to Zeebrugge, he may have shot down an enemy biplane, but this was unconfirmed.13

Armstrong was wounded in action on August 12, 1918 (and thus unable to participate in the next day’s raid on Varsenare). Pilots of the 17th had escorted DH.9 bombers of No. 211 Squadron R.A.F. to their targets near Bruges and were then involved in fierce fighting with Fokker DVIIs over Ostend. Todd much later recalled that “three of us [himself, Armstrong, and Harriss Percy Alderman] were coming back from Zeebruge when five Huns came down on us out of the sun and were firing at us before we saw them. Aldy’s guns jammed, and he was helpless as far as fighting was concerned. Army and I tried to put up a scrap, but it was impossible to do anything but protect ourselves, because of the odds. As it was, Army was shot up pretty bad. An explosive bullet hit his petrol tank and blew pieces of the tank into his back; altogether fourteen pieces by medical count. He also succeeded in getting two bullets through his arm. . . .”13a With one functional arm and barely conscious, Armstrong managed to reach the aerodrome and crash landed on top of a DH.9 of No. 211 Squadron. He was sent to nearby Queen Alexandra Hospital at Dunkirk. He was greatly relieved the next day to find that Alderman had also made it back. Both were still in hospital when King George arrived to inspect it, and conversed with him.14

The news of Armstrong’s injury spread, and the August 21, 1918, entry in War Birds reads in part: “Armstrong is in the hospital with an explosive bullet in his back.”

By mid-October Armstrong was well enough to rejoin his squadron—which had in the meantime, moved. It took him thirteen days to track it down. He was reassigned as a pilot on October 26, 1918, and appears in pictures taken at Toul in November 1918 of the 17th and of the 17th and the 148th together.15

On returning to the U.S., Armstrong resumed work as a painting contractor in Philadelphia; he moved to California sometime in the 1930s.16

mrsmcq April 15, 2017

Revised February 21, 2019 to reflect 209 Squadron record book

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Armstrong’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for William Joseph Armstrong. His date and place of death are taken from Ancestry.com, California, Death Index, 1940–1997, record for William Joseph Armstrong. The photo is cropped from the postcard described below.

2 See Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Thomas J Armstrong.

3 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

4 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 14, 1917; Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917; and Murton Campbell, Diary, entry for November 19, 1917.

5 The postcard, offered on ebay in February of 2015, has Armstrong’s name in ink on the address side.

6 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 91. See also the War Birds diary entry for March 12, 1918, where cadets at Ayr are listed.

7 Cablegram 745-S.

8 See cablegram 985-R. See also Ancestry.com, U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963, record for William J Armstrong; notes on his service appear on the verso. The notes indicate that he was commissioned a first lieutenant April 1, 1918, with active duty from April 6, 1918 (see McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205″). There was generally a time lag between the date of the cablegram and the date when the cadet was sworn in, and a further delay before active orders were received.

9 See the R.A.F. casualty form for Dixon (“Lieut. F A Dixon USAS”), as well as Munsell “Air Service History”, p. 192 (7) for Armstrong, p. 194 (9) for Dixon. NB: Armstrong’s casualty form is one of those at the beginning of the alphabet that is missing.

9a Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon and the 17th Aero Sqdn.,” p. 156.

9b See the R.A.F. casualty forms for Desson (“Lieut. Leonard Joseph Desson USAS”), and Lawton (“Lieut. Bradley Cleaver Lawton USAS”), as well as Munsell, “Air Service History”, p. 194 (9) for Desson, and p. 197 (12) for Lawton. Dixon kept two nearly identical group photos of 209 Squadron officers that include himself, Armstrong, and Lawton. See Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 45 and Jones, “As I Remember,” p. 38.

9c Here and in the subsequent description of Armstrong’s period with No. 209, information is taken from No. 209 Squadron Record Book (RFC/RAF). Where plane numbers and dates are hard to read, they have been cross checked against relevant entries in Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File.

9d See Great Britain, Royal Air Force, Royal Air Force Communiqués 1918, p. 102, on that day’s weather.

9e On 2 A.I. (Air Issues [section]) and its location, see mickdavis’s contribution to “Lieutenant Allen Denison.”

9f W.E.A. is apparently not a widely used abbreviation; it perhaps stands for “working enemy aircraft” (i.e., observation planes) or “wireless enemy aircraft/alert.” See “RAF abbreviation ‘W.E.A.’—special mission intercepting.”

9g C. N. Jones, “As I Remember,” p. 38.

9h See the entry for Summers on p. 355 of Shores, Franks, and Guest, Above the Trenches. I have not located a copy of the combat report. Unfortunately this credit apparently did not carry over to American records, which give Armstrong but one credit, from his time with the U.S. 17th Aero. See “Individual Victory List,” p. 54, the entry for him on p. 192 (7) of Munsell’s “Air Service History,” and p. 326 of Thayer’s America’s First Eagles.

10 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 156; Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 194 (9), gives June 25, 1918, as the date when Desson and Dixon were assigned to the 17th.

11 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 29.

12 See Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 24, and Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 35 and 40.

13 See the combat reports on pp. 58 and 61–62 of Clapp’s History of the 17th Aero Squadron, and see Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 49.

13a Todd, Sopwith Camel Fighter Ace, p. 78.

14 Clapp, on pp. 33–35 of his A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, provides an account that is worth reading. There is also a remarkable and gripping reconstruction of the mission of August 12, 1918, on pp. 51-53 of Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, based in part on information supplied to the authors by the pilots involved.

15 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 114; Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 160.

16 Ancestry.com, 1930 United States Federal Census, record for Wm Armstrong; Ancestry.com, U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963, record for William J Armstrong.