(Marblehead, Ohio, April 6, 1893[?]–near Misery, Somme, France, August 9, 1918).1

Training in England ✯ Fouquerolles ✯ Ruisseauville ✯ Touquin ✯ La Bellevue

Paskill’s paternal grandparents were probably French Canadian and his maternal grandparents English. Paskill’s last name appears as “Poskile” in early records, and his father’s name is written “John E. Poskile” in the record of his marriage to Louise Lee at Sandusky, Ohio, in 1885.

Reuben Lee Paskill was one of five children. His father was a farmer on Ohio’s Marblehead Peninsula; when the family relocated to Hastings, Michigan, early in the new century, he worked as a carpenter. Home life must have been troubled; Louise Paskill successfully petitioned for a divorce in 1907, charging cruelty; she and her ex-husband remarried two years later. In 1910 Reuben Lee Paskill was living in lodgings in Hastings; he graduated from Hastings High School the next year.2

Paskill was a good athlete, excelling in baseball, and his name appears frequently in the sports pages of various newspapers over the next years. In 1913 he was living in Chicago, where his older brother, Ira Lane Paskill, was also residing.3 That fall Paskill enrolled at the Armour Institute of Technology; he continued playing baseball, now on the Armour team.4 He completed his junior year, and in the summer of 1916 was among twenty students at an Armour Institute summer camp for “field practice in Surveying for Civil Engineers” in northern Wisconsin.5 Paskill did not return to Armour in the fall, but instead moved to Lynchburg, Virginia, and took a job as a civil engineer with the State Highway Commission, where his sister Grace Louise Paskill was also employed.6 Ira Paskill also moved to Virginia, settling in Richmond. By the time Paskill registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, both of his parents were dead, and in later records his brothers Ira and Earl are listed as next of kin.

An athlete and engineer, Paskill had the skills and training that the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps was looking for. In June 1917 he left his job in Virginia and, having been accepted for the A.S.S.C., went to Columbus, Ohio, to became a student at Ohio State University’s School of Military Aeronautics. Ground school lasted two months, from the end of June through the third full week of August 1917. As the men progressed through their course, rumors circulated about where they would go next. Initially it was thought they would be sent to Dayton, Ohio, and flying school, then that successful students would go to France to learn to fly. In mid-August there came a request for volunteers to train in Italy, and Paskill was among the large majority of students in his class who chose this option.7

The class graduated August 25, 1917.8 After some free time during which many of the men visited home, Paskill and the others expecting to train in Italy gathered at Mineola on Long Island. On September 18, 1917, they were ferried to the west side of Manhattan to board the Carmania at a Cunard pier in the Hudson River. They sailed initially to Halifax; from there, on September 21, 1917, the Carmania set out as part of a convoy to cross the Atlantic. The 150 men of the detachment travelled first class and had plenty of leisure, apart from Italian lessons given by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them.

Training in England

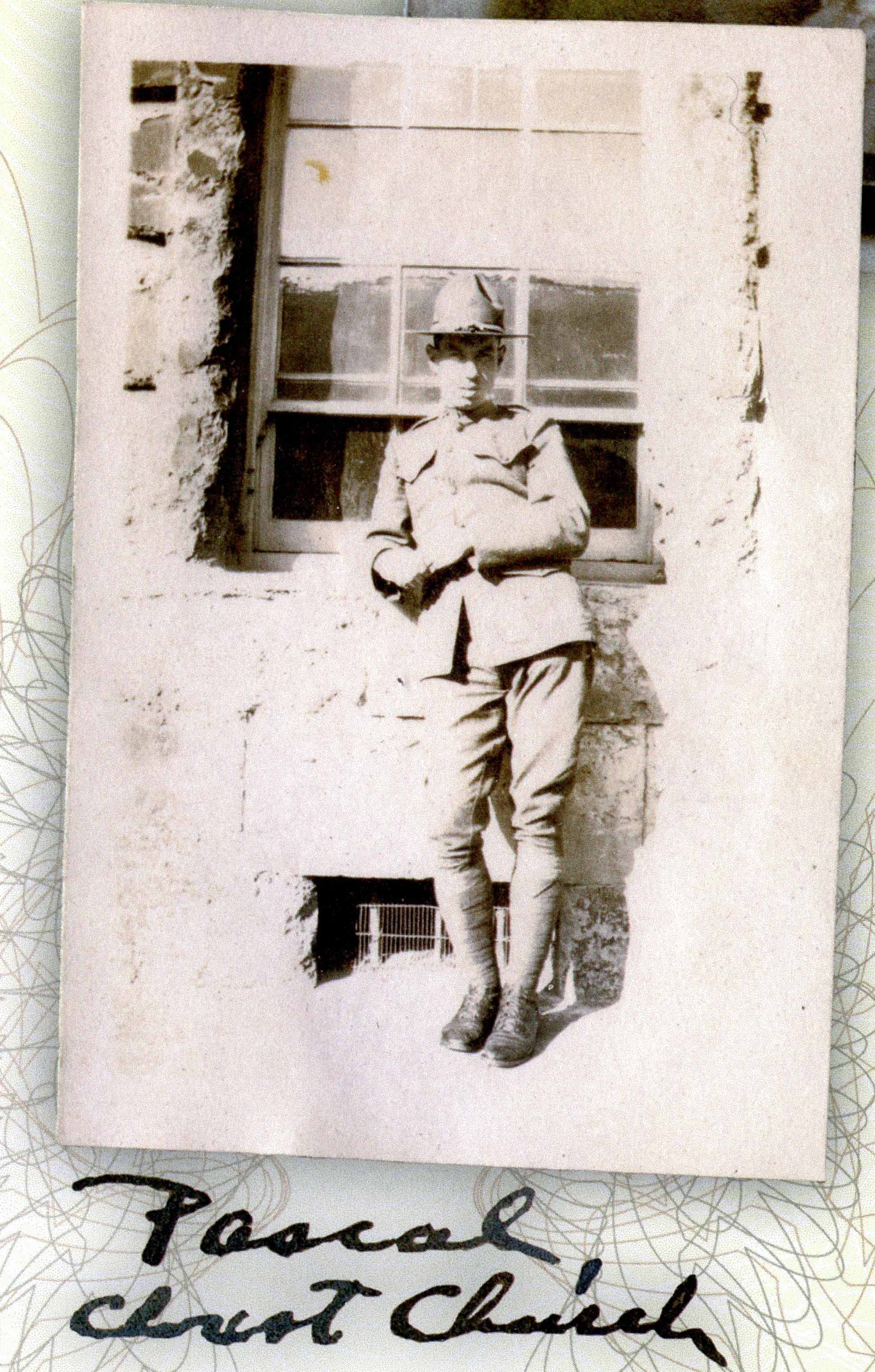

It was thus a surprise when, on docking at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the members of the “Italian detachment” learned that they would not continue overland to Italy, but would remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford. There was some grumbling, but the men fairly quickly settled into rooms at Christ Church and the Queen’s Colleges and life at Oxford. Much of the material covered in classes was not new, and the men had time to explore the town and the surrounding countryside. I find no written documentation of Paskill’s activities at Oxford, but he appears in at least three photos taken there by his fellow detachment member Joseph Raymond Payden.9 Men had apparently been assigned to state rooms on the Carmania in alphabetical order, and it seems likely that Paskill and Payden had become friends while roommates on the Atlantic voyage.

After a month, on November 3, 1917, twenty men from the detachment learned they would start flying training at Stamford, but the others, including Paskill, were sent north to take a machine gunnery course at Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire. As Parr Hooper, also sent to Grantham, remarked, “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”10 The men spent the next two weeks learning about and practicing with the Vickers machine gun. Just as they were finishing and facing the prospect of the next two weeks on the Lewis gun, they learned that fifty places had opened up at various R.F.C. squadrons, and Paskill was among those selected to fill them.

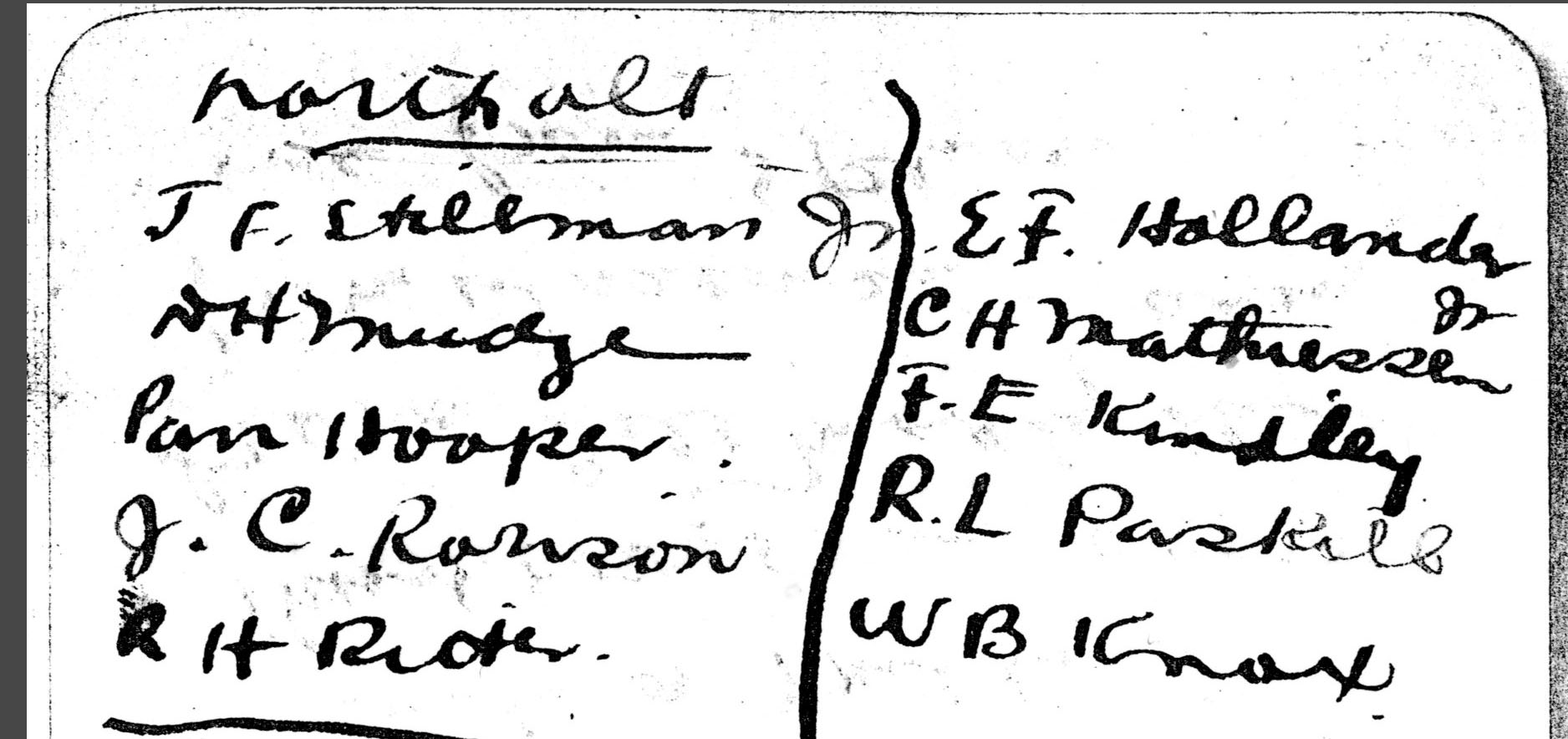

Along with Edward Frank Hollander, Hooper, Field Eugene Kindley, Walter Burnside Knox, Conrad Henry Matthiessen, Jr., Dudley Hersey Mudge, Roland Hammond Ritter, John Chadbourn Rorison, and Joseph Frederick Stillman, Jr., Paskill departed on November 19, 1917, for Northolt, on the northwest outskirts of London.11

Of Northolt, Hooper wrote: “Everybody here are officers except the mechanics. There are about 150 men training, 2 elementary squadrons and one advanced. We 10 Americans (5 in the 2nd squadron and 5 in the 4th squadron) are ranked as cadets but are treated as officers.” There is no indication as to which of the two training squadrons Paskill was assigned to, but the equipment and course appear to have been the same at both. Hooper continues: “The field is about ½ mile square. Lined on the north side are the hangars, large substantial corrugated iron ones, and behind them a row of shops and instructional rooms. On the adjacent side are the long low houses, so called huts. One group for the men and one for the officers. Also the headquarters, offices, and mess buildings. We live in nice, unfurnished rooms in the huts, 2 officers to a room and a man servant to each hut of 6 rooms. . . . The Major, the staff, flying instructors and all of us have the same mess.”12

Training began almost immediately—Hooper flew for the first time on November 22, 1917; Paskill’s experience was presumably similar. “In good calm weather flying goes on all day from sunrise to sunset with time out for the instructor to eat and have tea. The elementary squadrons use a very old type machine but one which they say is excellent to learn on because it has no inherent stability and must be flown (meaning controlled) all the time. In my flight there are two instructors (1st Lieuts with experience in France) 14 students and eight machines. We only fly in very calm weather. I have been here 4 days and have been up 3 times, total 65 minutes.”13 The “very old type machine” was the Maurice Farman S. 11 Shorthorn or “Rumpty,” ubiquitous at R.F.C. elementary training squadrons at this time. Matthiessen, Kindley, and Hooper are documented as having flown solo for the first time in early December, 1917, and, again, Paskill’s experience was presumably similar.14

After a month at Northolt, Paskill, along with Hooper, was posted on December 18, 1917, to No. 56 T.S. at London Colney, north of London and near St. Alban’s; they were the only two from their OSU ground school class at 56.15 However, quite a few others from the second Oxford detachment were assigned around the same time to either No. 56 or to No. 74 T.S., at the same field, and all began training on Avro 504s.

Winter weather and a relatively small number of planes meant that initial progress was slow; ten days after arriving at London Colney, Hooper wrote that “The past week has been rather discouraging. Too many clouds, too much wind, and too many Americans arriving.”16 Meanwhile, there was a good deal of socializing. On a Friday in mid-January 1918 “there was a good dance at St. Albans. About 15 from this squadron attended. Paskill and I walked up in the afternoon and had dinner with four other Americans. The dance was a very high class affair. It was arranged by several titled ladies, and the girls were the best I have seen in England. All the men were British officers or American cadets. . . . We danced until 2:45 a. m., and most all the girls had to go to work early that morning. ‘Pask’ and I stayed at the hotel in St. Albans all night and then walked to camp in the morning.”17

Flying instruction began to pick up. By early March 1918, Paskill had completed enough training and flying to qualify for his commission. Pershing forwarded the recommendation to Washington in a cable dated March 19, 1918; the approving cable came back dated April 2, 1918.18 Paskill was placed on active duty on April 18, 1918.19 By this time he was presumably in Scotland, where he would have taken a course in aerial gunnery at Turnberry before completing his final stage of training at the School of Aerial Fighting at Ayr—he appears in a group photo taken by Hooper at Ayr on April 27, 1918, as well as in photos taken there by Bogart Rogers. At Ayr, Paskill would have put in many hours on Spads and on S.E.5s, both single-seater fighter planes. He was still in Scotland on May 21, 1918, when he and his fellow second Oxford detachment members Hollander and Alexander Miguel Roberts were among the pall bearers at the funeral of George Clarke Squires at Doune Cemetery in Girvan.19a

Having completed his advanced flying training, Paskill may, like a number of others in his situation, have spent some time ferrying planes within England and from England to France. His next documented posting was to No. 2 A.S.D. on June 9, 1918, i.e., to the (British) pilots pool at Rang du Fliers, about twenty miles south of Boulogne, where men awaited orders to join a squadron.20 Paskill’s fellow second Oxford detachment member John Chadbourn Rorison took a photo of a group of men there that includes Paskill, along with several other men from the detachment.21

No. 32 Squadron RAF at Fouquerolles

On June 16, 1918, Paskill was posted to No. 32 Squadron R.A.F., where he would learn, if he did not already know, that the only other man from the second Oxford detachment assigned to the squadron, his friend Hooper, had been killed in action a week previously. Paskill would, however, encounter other Americans. Rogers, whom Paskill knew from Ayr, had arrived at No. 32 in early May, and Alvin Andrew Callender about two weeks later.

No. 32 Squadron, flying S.E.5a’s, was assigned to 9 Wing, IX Brigade.22 An R.A.F. brigade was generally made up of three wings; each wing in turn usually consisted of three or four squadrons. Each brigade was attached to a particular British army, whose number it took—with the exception of IX Brigade, which served directly under R.A.F. headquarters in France and could be sent wherever it was most needed.23 Or, as Callender described it: “we are attached to a mobile wing of the R.A.F., so that whenever you pick up a paper and read that there is a big offensive on, anywhere, you may know our squadron has been shoved right there for our usual jobs, ground strafing and escorting day bombers.”24 During Paskill’s time with 32, the squadron would move with IX Brigade from the French front in the south back north to the British front, and back south and then north once more.

When Paskill joined the squadron in mid-June, it was stationed at Fouquerolles, just east of Beauvais, on the French front. Most of IX Brigade, including No. 32 Squadron, had been sent there on June 3, 1918, in anticipation of the German offensive (“Gneisenau”) between Montdidier and Noyon towards Compiègne. This, the fourth of the five German offensives that had begun in the spring of 1918, had been successfully countered and halted after a few days (the Battle of Matz), and Paskill arrived at a relatively quiet front on June 16, 1918.

Quiet front or not, a newly assigned pilot would not have participated in flights over the lines until he had settled in and gotten to know the planes and the territory. Thus, on June 18, 1918, when the squadron conducted two offensive patrols, Paskill made a practice flight of forty-five minutes, and the next day another lasting thirty minutes.25

With No. 32 Squadron at Ruisseauville

Not long after Paskill arrived, the squadron learned that they were to move back to the British front. Baggage and equipment were packed off by ground transport for the journey north on June 20, 1918, leaving the pilots, who were to fly up the next day, at loose ends. Paris was not far away and, according to Rogers, “There was only one tender [transport vehicle] left and while Paris is out of bounds we asked the C.O. [John Cannan Russell] if we could have it, and he unofficially said we could. . . . So eight of us piled in and hied ourselves to gay Paree.” Paskill was apparently one of the eight, along with Callender, who enjoyed dinner and dessert of “real strawberry ice cream,” took in the sights, and then went on to Maxim’s, before heading back to the aerodrome around midnight.26

It was fortunate that rain prevented flying until late in the morning on the 21st, given that the forty-mile drive from Paris back north to Fouquerolles had taken three hours.27 Just before noon, 32 Squadron’s eighteen pilots took off in their eighteen planes for the hour’s flight to Ruisseauville in Pas-de-Calais, “further up than the aerodrome we were at before going south”—32 had been at Beauvois before moving to Fouquerolles.28 Paskill made the flight in S.E.5a C1836 without mishap.

Poor weather initially limited flying at Ruisseauville, and not until June 25, 1918, did Paskill get in another practice flight. Then, that same day, he took part in his first flight over the lines. The 32 Squadron record book designates the mission simply as an offensive patrol, but the S.E.5a’s of No. 32 Squadron were almost certainly providing escort to bombers. According to a squadron history, “[IX] Brigade conducted a two week experimental bombing campaign against railway targets. This started on 24 June. . . . A series of attacks was carried out on railway targets between La Bassée and Ypres, experimenting to see what forms of attack were most effective. The objective was to hinder enemy force concentrations in this sector of the front—railways being essential for large troop movements and supplies. 32 Sqn provided escorts to the bomber squadrons.”29 This same history refers to bomber squadrons “49, 98, 103, 107 Sqns all with DH9s,” but 32 also escorted the DH.4s and DH.9s of No. 27 Squadron, which, like 32, was stationed at Ruisseauville.30 The bombing remit actually extended farther south than La Basée, to Valenciennes and Douai.31

In any case, in the late afternoon of June 25, 1918, Paskill, flying D6884, was one of fourteen pilots who took part in the mission. “In typical stepped and separated three-group arrangement, . . . C Flight flew at 1000ft [sic; sc. 10,000 ft], the two other trailers some 1000ft to 3000ft higher.”32 I find nothing to indicate which flight Paskill was assigned to. One experienced pilot, Harold Charles Vizard, possibly Paskill’s flight leader, “returned early, unwell,” and Paskill and two other new pilots, Stanley Ewart Farson and Philip Thomas Alexander Reveley, “lost formation in clouds”33 and also returned early. Other pilots noted that visibility was bad and that they saw no enemy aircraft, but C flight leader Arthur Claydon, with the help of Callender and Rogers, shot down one of three two-seater fighter planes they encountered over Laventie, about thirty miles west-northwest of Ruisseauville and about eight miles over the lines.

Paskill made a further practice flight on June 26, 1918, and did not take part in that day’s offensive patrol. The next day, however, marked the beginning of his very active participation in the squadron’s work. Again in D6884, he flew and completed both the late morning and the early evening patrols—as Rogers remarked: “these lovely days are synonymous with two patrols”34—during neither of which were any enemy aircraft sighted. Paskill thus had an opportunity to learn the geography of the area without too much distraction before the next mission, “an escort for bombers in a lot of huge summer clouds” the evening of June 28, 1918.35 Rogers described this mission in a letter the next day: “Four Huns came down from the northwest in the sun and about a thousand feet above us. Two of our bunch—there were seven altogether—were up top, and the Huns went after them.”36 Twelve planes had set out, but five returned early, leaving Paskill, Rogers, Callender, Claydon, George Edgar Bruce Lawson, Wilfrid Barratt Green, and Hope Lawrence Wilfred Flynn to try to engage the Fokker DVIIs at 12,000 feet over Armentières. “The two tried to draw the Huns down under us. We had turned and were climbing, but they wouldn’t come even to our level.”37

Rogers, in the same letter, outlined 32 Squadron’s bomber escort work: “Just at present the bombers are taking off, which means we are due for an escort job in about an hour. The bombers always leave long before we do and climb and climb to get their height. Then we take off, get up to them in a few minutes, and take them across.” (Rogers notes elsewhere that “We never go all the way with the bombers, but patrol between them and the line.”38) “It’s the same coming home. We trail them over the line, and when they are well out of danger we pass them and are all washed up by the time they land.” As it happened, Rogers did not fly the mission on June 29, 1918, but Paskill, now flying S.E.5a D6909, was among the twelve pilots who did; no enemy planes were seen.

Paskill’s sixth offensive patrol was the second flown by No. 32 Squadron on the last day of June 1918. Escorting bombers of No. 27 Squadron, the twelve S.E.5a’s encountered enemy planes, an unusual combination of triplanes and biplanes, at 17,000 feet over Lille. Efforts to engage them were unsuccessful, “E.A. going East whenever patrol approached.”39

On July 1, 1918, Paskill once again flew two missions. The first was the usual bomber escort patrol, and, as on the preceding day, enemy planes encountered south of Lille escaped east. In the afternoon, however, according to Rogers, “we are going upon [sic] our own, a roving commission with nobody to worry about. Our instructions are to get Huns.” Despite, or perhaps because of, good visibility, no enemy planes were to be seen. It is worth noting that both of the patrols on July 1 were flown at high altitude, 18,000 feet in the morning,40 and in the afternoon some of the planes are reported to have reached 21,000 feet.41 There is no record of ill consequences. Presumably, particularly after pilot Arthur Edwin Brown suffered frost bite incurred during a flight on June 23, 1918, appropriate precautions were being taken.42

The next day, July 2, 1918, instead of a large patrol made up of two or three flights, each flight of six planes went out at a different time—as there were only fifteen pilots available, Callender, Walter Edwin Gilbert, and Arthur John Bateman flew twice. Paskill went out on the early morning patrol, led by Sturley Philip Simpson (which suggests that Paskill had been assigned to A flight43). On this, as on the two other missions that day, no enemy aircraft were sighted. At some point during his patrol, probably on the return leg, given his recorded total flying time of over two hours, Paskill’s radiator shutter jambed, and he had to land at Frévillers, about ten miles inside Allied territory; he did not get back to Ruisseauville until early afternoon.

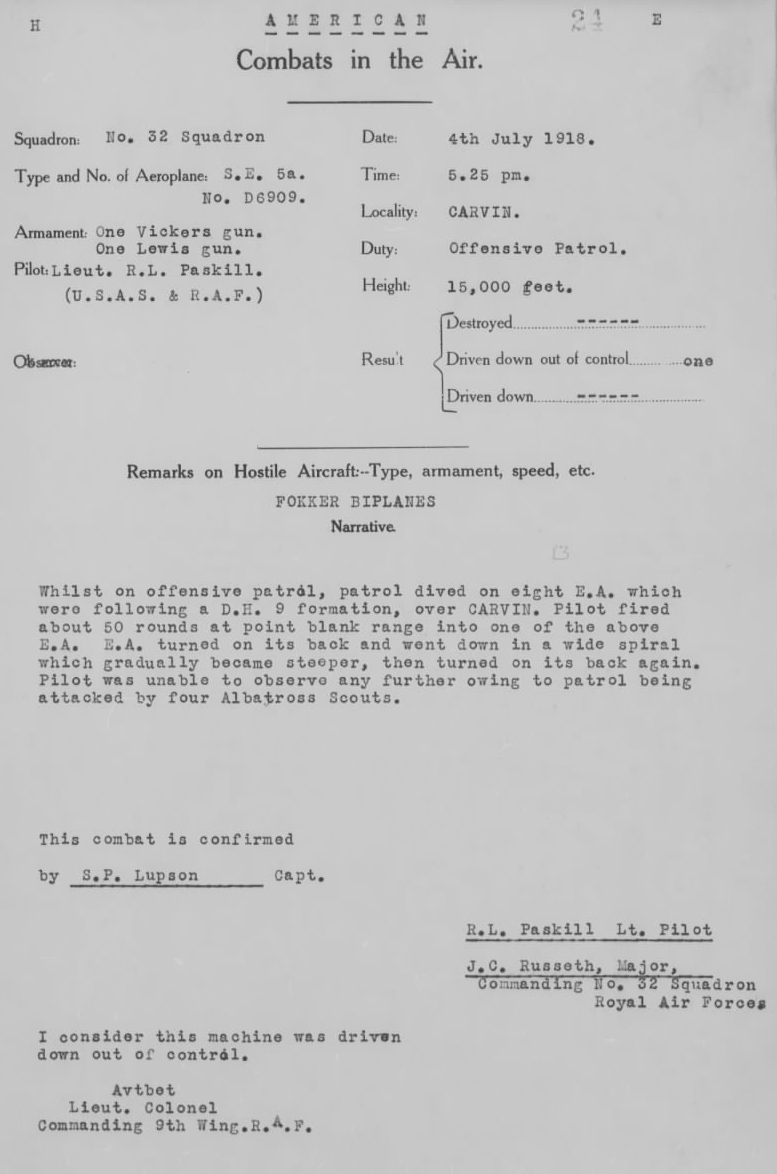

Wind and clouds precluded flying on July 3, 1918. The next day, however, “A couple of bombers had to go out and take pictures at three-thirty”44—bombers were also tasked with reconnaissance—and fourteen planes from No. 32 took off thirty minutes later to escort them. Mechanical problems forced two pilots (William Alwin Anderson and Flynn) to turn back early, and it appears that the remaining twelve flew in two formations, a higher and a lower of six planes each. The lower formation evidently included Simpson and Paskill; they “dived on 9 Fokker Biplanes over Carvin at 16000 feet at 5:25 pm.” Simpson “fired 80 rounds at one E.A.,” while Paskill “fired 50 rounds at one Fokker Biplane . . . from point blank range.”45 Paskill wrote in his combat report that “E.A. turned on its back and went down in a wide spiral which gradually became steeper, then turned on its back again.” Paskill “was unable to observe any further owing to patrol being attacked by four Albatross scouts.”46 32 Squadron’s higher formation then dived on the four attackers, which escaped east. All the pilots from No. 32 returned safely to Ruisseauville, in time for Fourth of July celebrations. When Paskill submitted his combat report claiming a plane driven down out of control, his account was corroborated by Capt. S. P. Lupson—presumably a pilot from the DH.9 squadron No. 32 was escorting (Paskill refers to DH.9s in his report).47 However, a plane not observed actually to crash was at this point in the war not regarded by the R.A.F. as definitely brought down, and Paskill is not credited, for example, in the R.A.F. communique for this period, although American authorities did award him a victory credit.48

Over the next seven days, Paskill flew four more missions, all in D6909: on July 7, 8 , 10, and 11, 1918 (32 flew no missions on July 5, 6, and 9, 1918). For the missions flown on July 7, 10, and 11, 1918, the record book notes laconically “No E.A. seen.” The mission of July 8, 1918, however, involved combat and losses. Rogers that day wrote that: “This morning we took the bombers across quite early, and when they were coming back about a dozen Huns came up after them. There were other of our machines out at the time and a large and wild dog fight ensued.”49

The bombers were apparently those of No. 27 Squadron, and their target perhaps railroad junctions south of Lille, or perhaps Tournai, about fourteen miles farther east.50 Sixteen planes from No. 32 set out at 6:30 a.m.; two, and then a third, had to return early due to mechanical problems. The thirteen remaining planes were divided into an upper patrol and a lower one, with Paskill apparently in the upper one with Simpson and Rogers (and others). The pilots in the upper formation “observed three Fokker Triplanes at 13000 feet West of Carvin at 8.-am. Ten E.A. Triplanes and Fokker Biplanes West of Carvin at 9000 feet being engaged by Camels, Bristol Fighters and our lower patrol”51—the Camels and Bristol Fighters (“other of our machines”) were apparently those of Nos. 73 and 62 Squadrons respectively.52 Rogers describes how the upper patrol “stayed up top, the idea being that if any Huns go down on our people, we can drop down on the Huns . . . I spied three red triplanes sitting at about our level and east of the scrap, so around and around we went watching the tripes. They wouldn’t come close to us or to the scrap, . . . They wouldn’t go down on anybody as long as we stayed up—so we stayed up.”53

The mission was a success insofar as bombs had been dropped and photos taken with no loss to the bomber squadron(s).54 When the pilots of No. 32 Squadron returned to the aerodrome at Ruisseauville, however, two pilots from their lower patrol were missing. It was eventually learned that Claydon had been killed in combat; Harold Walter Burry had been taken prisoner.55

With No. 32 at Touquin—the Second Battle of the Marne

In a letter written on July 11, 1918, Rogers remarked that “There’s a rumor that we may move again.” Two days later he wrote that “We’re up to the old tricks again, the transport has just departed and we’re hanging around waiting for orders to take airships down.” “A chap named Paskill—Chicago, U.S.A., U.S. Aviation Service, attached to RFC—and I are going into American corps headquarters and invite ourselves to meals. We know several fellows in there, and our mess left with the convoy this morning.”56

In the letter of July 13, 1918, Rogers also wrote that “From all indications the war is about to start again and we’re going to the lively spot.” And, indeed, squadrons of IX Brigade had been ordered back south to the French front in anticipation of what would be the Germans’ fifth and final push of their Spring Offensive, this time centered on Reims. In rainy weather, 32 Squadron pilots flew their planes the approximately 125 miles south-southeast to Touquin. Setting out at 8:30 in the morning, they planned “to make the whole trip without a stop if possible. We bucked a stiff wind from the start and ran into a heavy rain storm after about an hour. Nobody could see the way. Since it was obvious we would have to land for petrol anyway, we perched on a convenient French drome”—they landed near Etouy just east of Fouquerelles and more or less half way to Touquin, at 9:50. It was Bastille Day, and “the Frenchmen were celebrating.” The R.A.F. pilots were invited to a “six or seven course meal, everything and the trimmings to say nothing of the liquid refreshment”—which they indulged in lightly, knowing how much further they had to fly.57 All but Paskill set out again at 2:30; he was delayed an hour by oil pressure trouble in S.E.5a D6909, but arrived at the Touquin aerodrome, about thirty miles east of Paris, at 3:55. According to Rogers, the pilots were “comfortably billeted in a village near the aerodrome and have a large house for the mess”58—this is worth noting, as they had lived in tents at Fouquerolles and Ruisseauville.

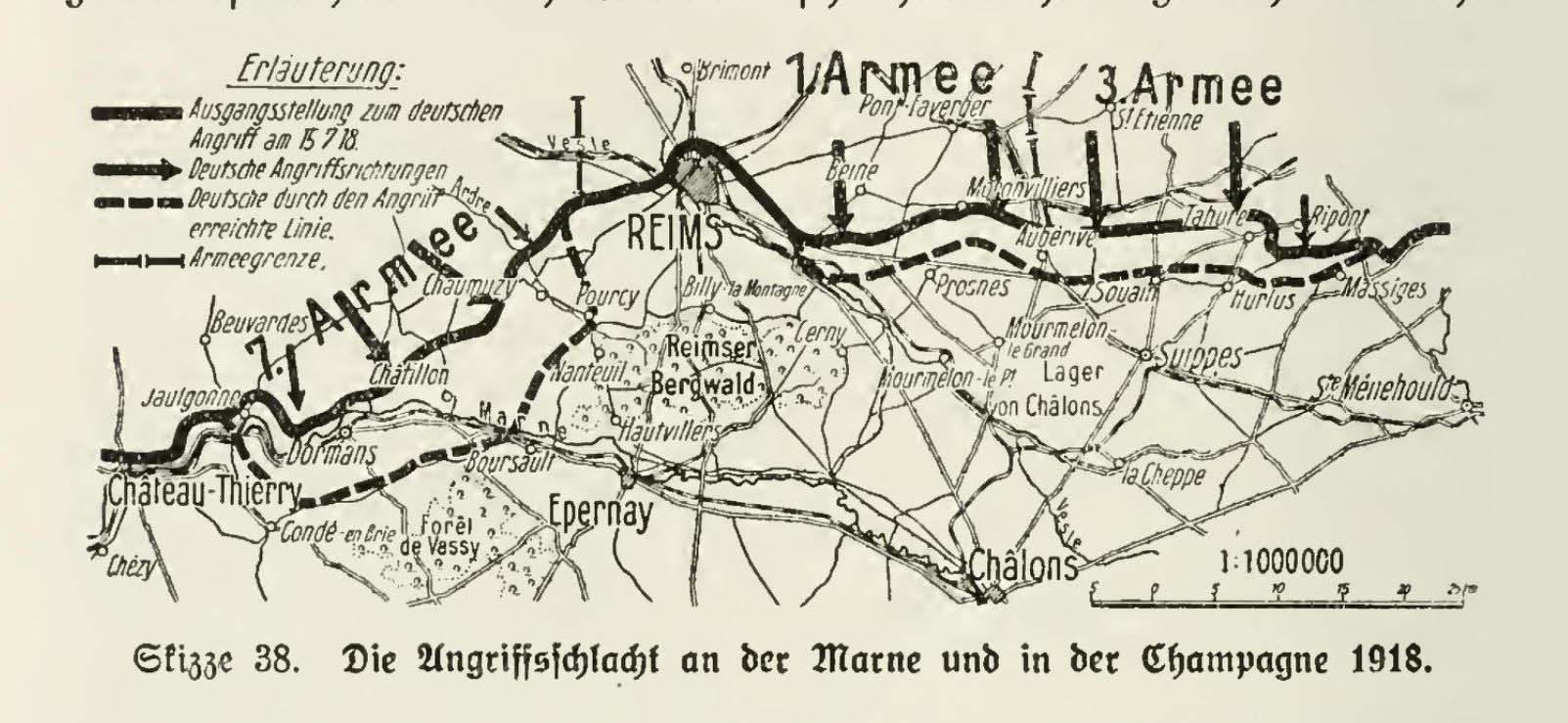

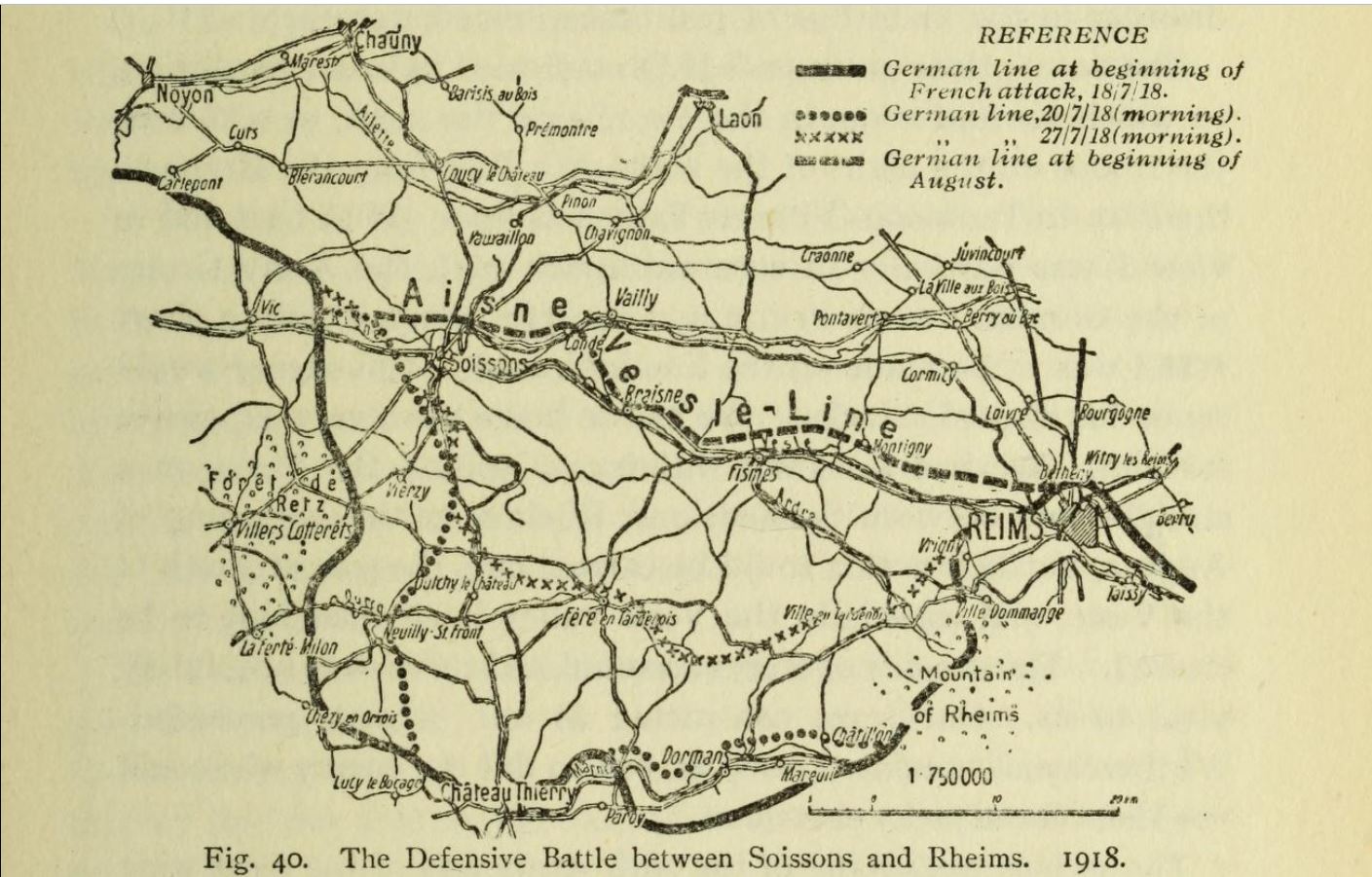

At midnight, “the German bombardment . . . opened with a crash that awakened the inhabitants of Paris to a new attempt to possess their city. At dawn, 4a.m., on the 15th, the German infantry moved.”59 “German attacks were launched to either side of the cathedral city [of Reims]. That to the east was completely shattered . . . . The advance between Reims and Château Thierry, however, made good early progress.”60 In his last letter from Ruisseauville, Rogers had written that “I wouldn’t be at all surprised if we were handed the sweet and popular old job of trench strafing altho everyone is praying ‘agin it’.”61 Rogers’s speculation was accurate: the first missions undertaken by No. 32 Squadron on the opening day of the Second Battle of the Marne on July 15, 1918, were “special missions”: bombing and strafing from low altitude, focussed on the area of “good early progress” by the German 7th Army, which succeeded in crossing the Marne in the vicinity of Dormans. IX Brigade squadrons made “attacks on the numerous footbridges thrown by the enemy across the Marne, some of which were destroyed by bombing.”62

The first two pilots from No. 32 Squadron (Green and Gilbert) set out at 11:45 a.m. on July 15, 1918, to bomb bridges at Dormans; two more (Rogers and Clifton Wilderspin) left at noon to attack targets on either side of the Marne just west of Dormans. At 12:40, eight more pilots, including Paskill, left Touquin to bomb and ground strafe the same general area; Paskill “dropped 2-25 lb. bombs from 1500 feet on bridge S.S.W. of Dormans at 1.15pm.” and “fired 300 rounds from 1000 feet into Rozay [Rosay] and Barzy,” just east of Jaulgonne on the far side of the Marne.63 The work was dangerous not only because of the intense ground fire, but also the presence of enemy aircraft. 32 suffered no combat casualties that day, but Richard Thornley Hall, who had been with No. 32 since November 1917, crashed when he landed back at Touquin. One of the bombs he was still carrying exploded, and he was badly burned when his plane caught fire.64 All the other men landed safely in a timely fashion, except Ralph Ellsworth Leet MacBean, who was a couple of hours late, having had to evade enemy aircraft, and Gilbert, who, for similar reasons, did not arrive back at the aerodrome until the next day.

After a two-hour break, No. 32 Squadron flew another mission, with 10 planes setting out at 4:30. Rogers implies that it was the same kind of mission as the previous one, but the squadron record book labels it an offensive patrol. Enemy planes were sighted flying at 12,000 feet on the far side of the Marne, but they “turned north every time patrol attempted to engage.”65 For some reason, Paskill got separated from the formation, and he landed S.E.5a D6909 “out of petrol” at “Escadrille Pri. [sic?; sc. Br.?] 126”66 at 7 p.m. Escadrille Br. 126 was at Linthelles, nearly forty miles due east of Touquin. Paskill set off again at 8:00, arriving thirty minutes later at his own aerodrome.

The pilots of 32 Squadron, including Paskill, again flew two offensive patrols on July 16, 1918, again to the same general area north of the Marne in the vicinity of Dormans and Jaulgonne.67 Eleven pilots—nearly all that were then available—set out in all the available planes in the late morning. They reached the Forêt de Ris between Jalgonne and Dormans north of the Marne around 12:30. They approached sufficiently close to a number of enemy planes flying at high altitude to be able to describe them in some detail and to fire at them, though without apparent result.

The sun set late in mid July in northern France, so the same pilots (less one) setting out again at 7:30 p.m. was not as foolhardy as it might initially appear. After thirty-five minutes and approximately the same number of miles, they were northwest of Jaulgonne, where they saw two Fokker biplanes, which flew north on their approach. Apparently divided into an upper and a lower patrol, the planes from No. 32 then flew southwest over Trélou-sur-Marne where, at 8:15, the lower formation encountered 25 enemy aircraft of various types flying at between 8,000 and 12,000 feet: “Patrol engaged and a general engagement ensued.”68 Green fired at one of the triplanes from point blank range, and he, William Earl Jackson, and MacBean saw it falling out of control. At the same time, if I understand the remarks in the record book correctly, planes from 32’s higher formation encountered ten enemy planes of various types at 16–17,000 feet. Rogers, temporary leader of A flight, fired at one of these, without apparent results.69 Assuming that Paskill had been and was still assigned to A flight, he would have been part of this upper formation. From Trélou, the pilots of 32 Squadron flew south-southwest and at 8:25 dived on five Pfalz scouts flying at 7000 feet over Courthiézy on the south bank of the Marne; the enemy planes escaped north. All the planes from this mission returned safely in the twilight between 9:10 and 9:25 p.m.

Paskill flew with the pilots of No. 32 on the next day’s single mission. During the early afternoon, in stormy weather, they flew slightly farther east than on the previous day’s flights; they encountered no enemy aircraft, but observed and reported “Heavy shelling on both sides on front Troissy–Oeuilly; French shelling being the heavier, throughout patrol.”70 The German advance was stalling.

The next day, July 18, 1918, Rogers wrote that “Our people staged a big push this morning.” The outcome of this major counter-offensive was that the “evident progress of the German forces to the west of Reims was driven to a complete standstill.”71 Over the course of the next two and a half weeks, the Germans would be driven back across the Marne and would lose the salient running south from Soisson to Château Thierry and from there northeast to Reims. In the short term, for the pilots of 32 Squadron, the Allied offensive meant they would, if I understand correctly, be flying protection for artillery cooperation aircraft.72 Thus on July 18, 1918, No. 32 Squadron went out twice in the morning and once in the late afternoon to protect and run interference for the Allied planes helping ground artillery pinpoint their targets—I find no information as to which squadrons they were working with.

Paskill flew the first morning mission; he was one of seven pilots who set out at 10:30. Rogers, who flew an hour later, described the work: “I led three other fellows up and down a small sector of line, quite low and the two seaters were working below us. There was a good deal of war going on, heavy shelling, tanks in action, and fires everywhere.”73 Paskill’s patrol an hour earlier sighted “One E.A two-seater, 8000 feet over Breny at 11:15am. Three E.A. two-seaters, 2500 feet over Noroy at 11:15 am. chased east beyond Nanteuil-Notre-Dame”—the patrol’s work was evidently focussed on the middle of the western line of the salient that ran south from Soissons to Chateau-Thierry. The patrol also reported “Intermittent heavy shrapnel barrage on North East edge of largest wood West of Chateau-Theirry [sic] between 11. and 11.45am.”74 Two pilots returning from this mission, Gilbert and Green, landed at La Ferté Gaucher, some fourteen miles east of Touquin. Paskill made it back to Touquin, but crashed on landing. Callender’s editor infers that the planes of all three pilots had been damaged flying low over the German shrapnel barrage.75 Unlike the unfortunate Hall, Paskill was not carrying bombs when he crashed. He was uninjured, but S.E.5a D6909 was extensively damaged and had to be written off.76

Paskill did not fly either of the other two missions on the 18th, but, now flying E1327, took part in the single mission flown the next day, and then every day for the rest of July, with the exception of July 23 and 27, 1918, when no missions were flown. Remarks by Rogers as well as notes in the squadron record book indicate that the planes of No. 32 Squadron were once again flying protection for bombers, perhaps again those of No. 27 Squadron, which was stationed at nearby Chailly-en-Brie.

On July 22, 1918, No. 32 flew two bomber escort missions,77 and Paskill took part in both. In the morning he flew S.E.5a C1836, but in the late afternoon he was once again flying E1327, which would be his plane for all his remaining missions. The afternoon mission involved flying considerably farther northeast than previously. Over Mont-Notre-Dame, forty-five miles northeast of Touquin, the S.E.5a’s encountered twenty Fokker biplanes and triplanes at 17,000 feet and “ended up in a gosh awful dogfight.”78 Four pilots filed combat reports, and the mission would have been entirely successful, but that “Coming home archie got a direct hit on one of the bombers”—evidently DH.9 D490 of No. 27 Squadron; both crew members were killed.79

The next day’s rain precluded missions, and Paskill and Rogers took the opportunity to go to Paris. They “went down to the American University Union, put our names on the book, and looked thru the registers. . . . After that we met the rest of our gang—there were eight of us altogether at Maxim’s and had dinner. . . . We rode home in a nice seven passenger Packard belonging to one of the American squadrons”80—the U.S. 95th Aero Squadron was stationed nearby at Saints.

Paskill flew both the morning and the evening mission the next day, July 24, 1918. Enemy aircraft were out in force in the vicinity of Fère-en-Tardenois at different altitudes in the morning when visibility was good, but were discouraged from their effort to interfere with DH’s. In the evening, the patrol went even farther east, to Savigny-sur-Ardres, just short of Reims; the single aircraft encountered dove into clouds when attacked. Paskill did not fly the next day’s morning mission, but took part in the one that set out at 5:45 p.m. on July 25, 1918. That day, according to the relevant RAF communiqué, “Enemy aircraft not particularly active, except on the French battle-front in the evening”81—where and when the pilots from 32 were flying. At 7p.m. over Fismes, fifty miles northeast of Touquin, thirteen S.E.5a’s of No. 32 squadron encountered seven Fokker biplanes at 12,000 feet, another twelve at 14,000 feet, and yet four more at 19,000 feet. A general engagement ensued. Paskill “fired 300 rounds at 4 different Fokker biplanes, but no results were observed owing to close proximity of other E.A.” Several other pilots involved in the fight were able to observe their targets going down and filed combat reports. One pilot from No. 32, Harry Marinus Struben, on this, his first flight over the lines, was shot down and taken prisoner; all the others returned safely.82

The editor of Callender’s letters writes that the dog fight the evening of July 25, 1918, “marked the end of the squadron’s participation in what came to be known as the Second Battle of the Marne,”83 and it is true that the pilots of No. 32 Squadron did not again engage enemy aircraft while based at Touquin. They did, however fly several more missions. Rogers describes a morning mission on July 26, 1918, in which Paskill also took part, as one in which they “quite uneventfully escorted a lot of bombers while they put a Hun aerodrome out of business.”84 The last offensive patrol flown by No. 32 squadron from Touquin was a small (five plane) formation that set out at six in the evening of July 30, 1918. On this, Paskill’s thirty-second mission, two enemy aircraft were sighted, but they “made N.E. on approach of patrol.”85

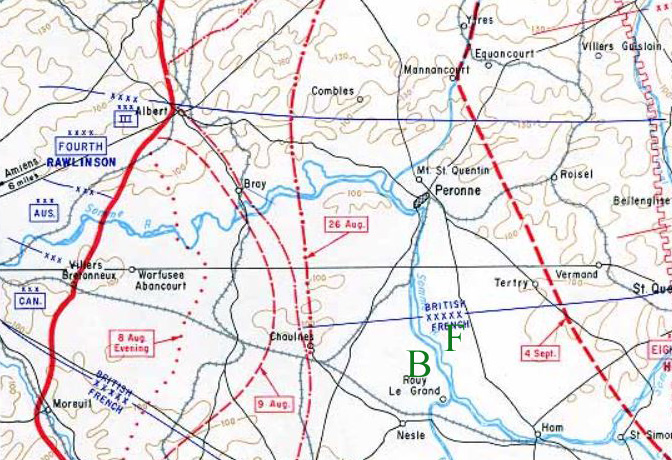

At La Bellevue on the British Front—the Amiens Offensive

At the end of July and the beginning of August 1918 preparations were quietly being made by the Allies for a major offensive to the east of Amiens, and the squadrons of IX Brigade were yet again relocated, moving back to the British front. The afternoon of August 3, 1918, No. 32 Squadron C.O. Russell and his eighteen available pilots flew one hundred miles north from Touquin to an aerodrome at La Bellevue. Not quite as far north as they had been at Ruisseauville, they shared the aerodrome with No. 73 Squadron, which flew Camels. Rogers was on leave, but Callender was not, and the latter wrote the next day: “Flew over Paris on our way back up North yesterday, and through two rain storms. This is the fifth aerodrome I have been on in three months I have been out now and it is right up on the lines almost. So that the guns keep us awake at night. The Hun observation balloons four or five miles on their side of the lines are faintly visible from my tent.”86 The continuation of Callender’s letter suggests that plans for what came to be called the Battle of Amiens were being kept well under wraps: “The worst three months is over now as far as air work is concerned. Rain this month, and cold and snow from then on keeps the Hun out of the sky better than we could. So until next spring three or four patrols a week will be about the extent of our labor.”

On August 7, 1918, fifteen pilots, including Paskill, from 32 Squadron performed a two-hour offensive patrol, with what objective I cannot tell. The record book simply states “Visibility poor. No E.A. seen. Other observations nil.”

The Allied offensive, a complete surprise to the Germans, opened at 4:20 a.m. on August 8, 1918, the day Erich Ludendorff recalled as “the black day” for the German army.87 It had been planned that bombers escorted by scouts would attack German aerodromes on the Fourth Army front at daybreak,88 and it is possible that the S.E.5a’s of 32 Squadron were tasked with such escort duties when sixteen of them set out at 8:20 a.m. However, a thick low mist meant those flying could not see the ground, and the “Patrol returned early on account of bad weather.” (I should note that the squadron record book has Paskill flying S.E.5a E1329 on this mission, almost certainly a typographical error for E1327.)

Once the mist cleared it was apparent that German troops were in great disarray, “and exceptional targets were offered to the low-flying single-seater pilots.” Around midday, “pilots and observers reported that the roads leading to the Somme crossings were becoming crowded with retreating German troops and transport. If the bridges, . . . could be broken, the enemy troops west of the Somme would find themselves compressed within the pocket of land made as a result of the abrupt change of course which the river Somme takes at Péronne.”89 The R.A.F. “cancelled . . . all existing arrangements for bombing in the afternoon . . . and ordered, instead, attacks upon the Somme bridges, which were to be bombed ‘as long as weather and light permits’: the fighter squadrons were to take part by dropping bombs of 25-lb. weight.”90 Thus, rather than continuing their bomber escort work, the pilots of No. 32 Squadron were themselves tasked with bombing bridges across the Somme south of Péronne.

At 1:45 p.m. twelve pilots from 32 set out for Béthencourt-sur-Somme, thirty-five miles southeast of La Bellevue. According to the official history, during this “first attempt on Bethencourt ten D.H.9’s [of No. 49 Squadron] and twelve S.E.5a’s [of No. 32 Squadron] took part, but German fighters engaged the bombers before the objective was reached, and no more than four D.H.9’s and three S.E.5a’s attacked the bridge: the remainder dropped their bombs on divers places.”91 The 32 squadron record book provides a more nuanced (or confusing) picture. Paskill and John Owen Donaldson (an American who had joined the squadron on July 10, 1918) were east of the Somme at 2:45 and dropped their bombs, respectively, on the railway at Foreste, and on enemy troops at Ugny. Meanwhile, Simpson, MacFarlane, and Callender were over Béthencourt; the first two dropped their bombs on the town, and Callender on the bridge, as did around 3:00 Alan Keith Whiteman, Gilbert, and Reveley. The only mention of enemy aircraft in the record book’s remarks on this mission come from Joseph Brown Bowen, who, attacked by four Fokker biplanes at 3:00, was unable to see the results of his bombs dropped on an aerodrome west of Echeu, six miles south of Béthencourt. All the pilots returned safely (Green having dropped bombs east of Pertain at 2:40, short of Béthencourt, while both Lawson and Farson got lost and did not drop their bombs).

Nearly all of the pilots from the first mission set out again at 4:45 with the same objective, and this time eight of the eleven pilots, including Paskill, were able to drop their bombs on the bridge at Béthencourt from an altitude of just 1000 feet between 5:15 and 5:30. Most were unable to see the results of their efforts, but on this occasion Paskill saw one burst on the eastern approach to the bridge. He was also able to report that a trestle bridge was being erected a kilometer north of Béthencourt. Again the official history—presumably focussed on 49 Squadron records—suggests a different picture, stating that “The Germans intercepted the British pilots at about 1,000 feet, just when they were diving on the target, and the result was that the bombs could not be aimed with precision.”92 But Green, with 32 Squadron, reported “No E.A. seen,” and there are no other mentions of enemy aircraft on this mission in the record book until the remarks about Donaldson, who engaged a Fokker biplane over Licourt at 6:15.93 All the pilots of No. 32 Squadron returned safely from this, the third mission of the day.

The Somme bridges continued to be the main target of IX Brigade squadrons the next day, August 9, 1918, but, apparently because of the experience of, for example, 49 Squadron on the preceding day, scouts were to return to their escort duties. According to the orders issued for the day, “ ‘It is reported that during [August 8] operations, enemy aircraft scouts molested our bombers . . . and prevented them from carrying out their missions effectively. Wing commanders will, therefore, detail scouts for close protection of bombers. . . ’.”94

The first mission flown by No. 32 Squadron set out at 9:45. Although there is information on the pairings of bomber and fighter squadrons for the missions that set out very early in the morning, I find no record indicating which bomber squadron, if any, the fourteen pilots of No. 32 were to escort on this, their first mission this day.95 They flew to the same general area as on the preceding day. Paskill reported sighting Fokkers and Camels engaged in combat over Hyencout at 10:30. Thirty minutes later, over Licourt, just short of the Somme River, at 11,000 feet, he saw Donaldson engaged in combat with three Fokkers. One of them, according to Donaldson, burst into flames when he, Donaldson, fired at it. One of the remaining Fokkers, now at about 7,000 feet, attacked Donaldson, and Paskill fired seventy-five rounds at it. Donaldson’s plane was damaged, and he was forced to land at No. 3 Squadron A.F.C., which was stationed at Villers-Bocage, some fifteen miles south-southeast of La Bellevue. Pilots of 32 flew farther east and south across the Somme, encountering Fokker biplanes at 10,000 over Villers-Saint-Christophe, and at 18,000 feet over Athies—where pilot Reveley was last seen; it was later learned that he was wounded and had been taken prisoner.96 All the other pilots returned safely to La Bellevue.

German leaders soon realized the importance of protecting the Somme bridges and significantly increased German aerial activity in the area. This motivated a change of tactics on the part of the R.A.F. in the afternoon of August 9, 1918. In a mass attack, each of four bomber squadrons (49, 27, 107, and 98) was to attack a different Somme bridge at precisely the same time, 5 p.m., and they were to be heavily protected by fighter squadrons, some of which would patrol the area and some of which would provide close escort.97 No. 49 Squadron’s D.H.9s were to attack the bridge at Falvy, just north of Béthencourt, and No. 32 Squadron was to provide protection.

Thirteen 32 Squadron pilots, including Paskill, set out at 4:05 p.m. The remarks related to this mission in the record book state that at 4:40 eight Fokker biplanes were encountered at 5,000 feet over Misery—just west of the Somme and a bit north of Falvy—and driven east, and that three minutes later twelve more appeared at 3,000 feet in the same location. The official history speculates that these twenty planes were the ones that shortly thereafter attacked the D.H.9s of 49 Squadron, preventing the bombing of the bridge at Falvy. What matters for this history, however, is that, according to the squadron record book, Paskill’s plane was last seen at 4:40 at 5,000 feet over Misery.

Historians of World War I aviation have noted that Rudolf Klimke, a pilot with Jagdstaffel 27, which took part in the defense of the Somme bridges, was credited with having shot down an S.E.5a south of Bray-sur-Somme at 5:12 p.m. on August 9, 1918, and have tentatively identified that S.E.5a as Paskill’s plane.

Paskill’s name appeared on a list of those missing in action published in U.S. papers in mid-September 1918. Friends in Hastings, Michigan, seeking news of his fate, are reported in July 1919 to have received the dispiriting news that “Search reveals no trace of Lieut. Reuben Paskill.”98

In January 1923 Ira Lane Paskill received a letter from a Walter Sickmeier [Siekmeier?] of “Horde, Westphalen” [Hörde, south of Dortmund], Germany. Sickmeier’s original attempt to contact Paskill’s family apparently went astray, and it was not until late 1922 that he was able to find a correct address for Ira Paskill. According to a newspaper transcription of the translated letter, Sickmeier wrote that he “was with your mortally wounded brother who was killed when his plane crashed to earth in August 1918. He died in my arms and I had him buried together with one of our own comrades with military honors. . . . I still have in my possession the silver identification medal of your brother which according to the rules of the Zeufer [sic; sc. Genfer, i.e., Geneva] convention, we removed from his body before burial. . . I shall send the same to you together with an arm bracelet and a card which will enable you to find the grave of your brother.”99

Paskill’s name is recorded on the Tablets of the Missing at the Somme American Cemetery and Memorial, some twenty miles east-north east of where his plane was last seen by his fellow squadron members.

It is possible that he is listed as missing because Sickmeier’s information was not conveyed to American authorities, but it is also possible that the intense fighting that was still to take place on the Somme after Paskill was shot down and buried obscured his grave site. At present (September 6, 2021) covid restrictions limit access to the National Archives, National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri, where there may be a burial file for Paskill, which might throw light on the issue.

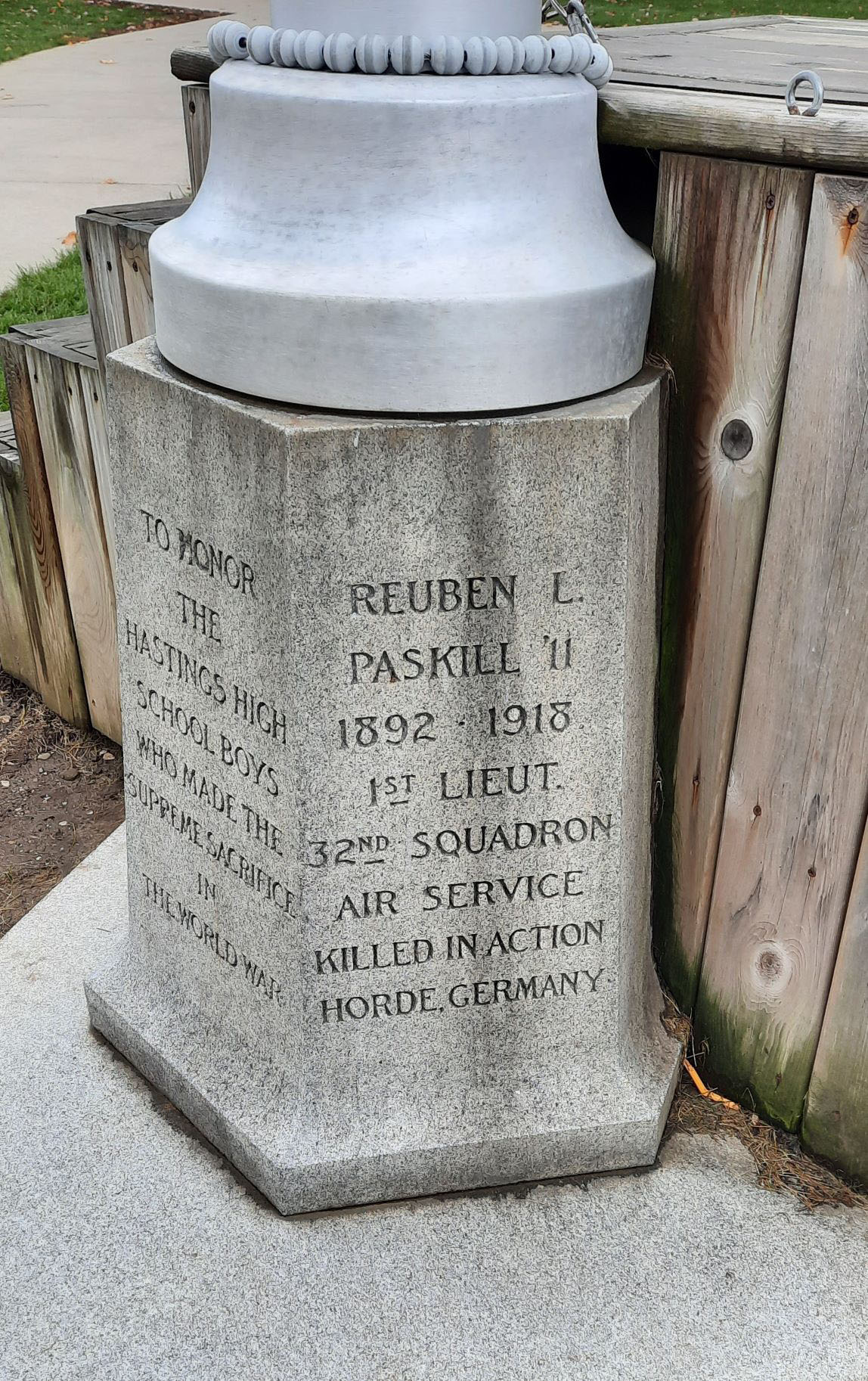

In 1926 the alumni association of Hastings High School erected a memorial to commemorate two graduates who lost their lives in World War I: Paskill, from the class of 1911, and U.S. 11th Aero Squadron member Laurence James Bauer, from the class of 1913. The original high school building has been replaced by a new structure, now the town’s middle school. The memorial, which forms the base for a flag pole, still stands.

mrsmcq September 7, 2021

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 I have taken Paskill’s place and date of birth from his draft registration; see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Reuben Lee Paskill. However, two other records, probably reliable, give his year of birth as 1891; see Ancestry.com, Ohio, U.S., Births and Christenings Index, 1774-1973, record for Ruben E. Poskile [sic], and Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Rheuben Poskile [sic]; the former gives his place of birth as Danbury, Ohio. Paskill’s place and date of death are taken from the RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book. The photo is a detail from a group photo of his ground school class at O.S.U.

2 Information on Paskill’s family and descent is taken from records (census, marriage, divorce) available at Ancestry.com. On his high school class year, see the Hastings, Michigan, High School yearbook for 1916, p. 98.

3 See the relevant entries in Donnelley, The Lakeside Annual Directory of the City of Chicago 1913.

4 “Armour Ball Player Downs First Plane.”

5 “College Notes,” p. 79.

6 See Virginia State Highway Commission. Annual report, pp. 100 and 108.

7 Information on the rumors is taken from unpublished letters of Parr Hooper in my possession.

8 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

9 Payden and Payden, compilers, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925, pp. 25, 26, and 27.

10 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

11 See Foss, diary entry for November 15, 1917, for a list of the men assigned to Northolt. See Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917, regarding their departure.

12 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917.

13 Ibid.

14 On Matthiessen and Hooper, see Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 4, 1917; on Kindley, see Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 24.

15 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of January 8, 1918.

16 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 28, 1917.

17 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of January 21, 1918.

18 Cablegrams 750-S and 1028-R.

19 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

19a Rees, Letter to Mrs. George C. Squires.

20 “Lieut. Reuben Lee Paskill USAS”

21 Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 43.

22 See “No 32 Squadron RFC/RAF 1918: A Brief History.

23 On the role of IX Brigade, see Callender, War in an Open Cockpit, p. 57, note 3; on the composition of brigades and the role of IX Brigade, see McCluskey, “The Battle of Amiens and the Development of British Air-Land Battle, 1918-45,” pp. 232-33.

24 Callender, War in an Open Cockpit, letter of July 21, 1918.

25 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book. Unless otherwise noted, further details regarding Paskill’s participation in missions are taken from this record book.

26 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of June 21, 1918.

27 Callender, War in an Open Cockpit, letter of June 24, 1918.

28 Ibid. Chamberlain, “A Short History of No. 32 Squadron,” p. 51, states that No. 32 relocated on Jun 21, 1918, to Planques, and then, on July 9, 1918, to Ruisseauville; I believe this is incorrect. See the entry for No. 32 Squadron in Jefford, RAF Squadrons. Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, in his letter of July 10, 1918, remarks “Yesterday we did nothing”—a relocation, even the short distance from Planques to Ruisseauville, would have merited mention.

29 “No 32 Squadron RFC/RAF 1918: A Brief History.” And, for a fuller account of this bombing campaign, see Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, pp. 407– 11.

30 See Taylor, “Captain Arthur Claydon DFC,” pp. 303 [?] ff. And see the relevant entry in Jefford, RAF Squadrons on 27’s location and equipment. Note: if I read Jefford correctly, he indicates that 27 Squadron only began receiving DH.9s in September 1918; a quick glance at the casualties recorded for 27 on, for example, June 16, 1918, in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, reveals that the squadron was flying both DH.4s and DH.9s at this date.

31 See Taylor, “Captain Arthur Claydon DFC,” p. 305 [?], which indicates that No. 27 Squadron conducted a bombing raid in the vicinity of Douai; and see Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 407, which lists the Valenciennes railway junction as a target of this “Bombing Scheme.”

32 Taylor, “Captain Arthur Claydon DFC,” p. 304 [?].

33 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book

34 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of June 27, 1918.

35 Ibid., letter of June 29, 1918.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid., letter of July 1, 1918.

39 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book. On this day’s encounter, see also Taylor, “Captain Arthur Claydon DFC,” p. 307 [?].

40 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of July 1, 1918.

41 Taylor, “Captain Arthur Claydon DFC,” p. 307 [?].

42 Callender, War in an Open Cockpit, letter of June 24, 1918.

43 See Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letters of May 12, 1918, and July 10 [11], 1918, regarding Simpson as leader of A flight.

44 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of July 6, 1918.

45 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book.

46 Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F., p. 24.

47 I have not been able to identify Lupson and suspect that his name, like those of Major Russll and Lt. Col. Alwyn Vesey Holt, was mistranscribed in the copy of Paskill’s combat report in Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F. I have not been able to find a copy of the report in the records of No. 32 Squadron at the National Archives (UK).

48 See Great Britain, Royal Air Force, Royal Air Force Communiqués 1918, and “Confirmed Victories U.S. Air Service Officers Attached to Royal Air Force Squadrons.”

49 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of July 8, 1918.

50 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 409, lists “The Fives junction south of Lille” and “Tournai junction” among the bombing targets of the IX Brigade bombers in late June through early July. The editor of Callender, War in an Open Cockpit, p. 64 , note 13 (where for “the 9th” read “the 8th), states that “the day bombers dropped two tons of bombs on Lille Junction.” Taylor, “Captain Arthur Claydon DFC,” p. 308 [?], states that Tournai was No. 27 Squadron’s “designated target.” I should perhaps mention being puzzled that the official history (Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6) makes no mention of 27 during the bombing campaign conducted while 32 was at Ruisseauville, while Taylor makes no mention of the IX Brigade bombing squadrons.

51 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book.

52 Taylor, “Captain Arthur Claydon DFC,” p. 307 [?].

53 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of July 8, 1918.

54 Taylor, “Captain Arthur Claydon DFC,” p. 308 [?]; Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, entries for July 8, 1918.

55 Taylor, “Captain Arthur Claydon DFC,” passim; The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Harold Walter Burry.

56 See Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF.

57 Quotations are from Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of July 18, 1918.

58 Ibid.

59 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 413.

60 Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, p. 189.

61 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of July 13, 1918.

62 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 414.

63 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book.

64 See “Hall, R.T.”

65 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book.

66 Ibid.

67 “No 32 Squadron RFC/RAF 1918: A Brief History” indicates that these were flown to protect artillery contact patrols.

68 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book

69 See Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, p. 144: Rogers notes that Simpson was serving as C.O. while Russell was on leave, and that he, Rogers, was leading A flight.

70 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book

71 Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, p. 190.

72 This description is based on Rogers’s description in his letter of July 18, 1918: “The morning show consisted of a protective patrol for artillery machines doing contact patrol.”

73 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of July 18, 1918.

74 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book.

75 Callender, War in an Open Cockpit, p. 69.

76 I am grateful to Andrew Pentland for a copy of the aircraft casualty report related to this crash; the original is at the National Archives (UK), Air 1/857/204/5/413.

77 See “No 32 Squadron RFC/RAF 1918: A Brief History” regarding the type of mission.

78 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book, and Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of July 24, 1918.

79 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of July 24, 1918, and relevant entry in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II.

80 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of July 24, 1918.

81 Great Britain, Royal Air Force, Royal Air Force Communiqués 1918, p. 140.

82 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Harry Marinus Struben.

83 Callender, War in an Open Cockpit, p. 70.

84 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, letter of July 27, 1918. I have not been able to identify the German aerodrome.

85 RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book.

86 Callender, War in an Open Cockpit, letter of August 4, 1918.

87 Ludendorff, Meine Kriegserinnerungen 1914–1918, p. 547.

88 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 433.

89 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, pp. 440–41.

90 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 441.

91 The War in the Air, vol. 6, pp. 441.

92 See also Henshaw’s comments with respect to No. 49 Squadron in the entries for August 8, 1918, in The Sky Their Battlefield II.

93 See also Donaldson’s combat report in Air combat reports: 32 Squadron Royal Flying Corps (AIR 1/1222/204/5/2634/19).

94 Cited in Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 446.

95 Callender’s editor, War in an Open Cockpit, p. 83, indicates the target of 32’s raid was two bridges at Falvy.

96 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Philip Tom Alexander Reveley

97 Jones, The War in the Air vol. 6, p. 449.

98 “Search in Vain for Missing Hastings Flyer.”

99 “Body of Richmond Officer is Finally Located in Germany.”