(Clarendon County, South Carolina, September 3, 1894 – S.E. of Grandcourt, Somme, France, July 9, 1918).1

Oxford and Grantham ✯ Waddington ✯ Marske ✯ No. 48 Squadron R.A.F. ✯ Afterwards

Shaw’s paternal ancestry has been traced back to a John Patrick Shaw of Scottish descent who came to South Carolina from Ireland in 1772.2 Shaw’s mother, born Mary Lula Alderman, was descended from a William Alderman documented in Connecticut in 1672. The latter’s grandson, Daniel Alderman, brought his young family to North Carolina in 1755, where his descendants resided for several generations until David Wells Alderman removed with his family to Clarendon County in South Carolina soon after 1880. There he founded the town of Alcolu and established what became an extensive timber and lumber business.3 David Charles Shaw worked for Alderman and in 1892 married Alderman’s daughter, Mary Lula Alderman. Ervin David Shaw was their first child. Not long after their youngest child was born in Alcolu in 1909, David Charles Shaw moved his family to the town of his birth, Sumter, and entered into the automobile business.4

Ervin David Shaw, who at some point acquired the nickname Molly, attended schools in Sumter before beginning studies at Davidson College in North Carolina in the autumn of 1911.5 After 1912, his interest in cars seems to have become paramount, and he apparently did not complete a degree.6

According to his R.A.F. service record, Shaw was “in the auto business” from 1913 until 1917.7 His name appears in advertisements for cars in Sumter newspapers in 1914, and the following year articles about his involvement in auto racing begin to appear.8 When Shaw registered for the draft he indicated he was an auto salesman and listed his various positions in Sumter auto companies.9 He also noted that he had been a member of the South Carolina National Guard for four years.

In June of 1917 Shaw applied to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and was accepted; he set off to attend ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University at the end of the month.10 Shaw’s class graduated September 1, 1917.11 Many men in this class and the preceding one chose or were chosen to do their further training in Italy, Shaw among them. He was able to make a brief visit home at the end of September before joining the 150 cadets of the “Italian detachment” who would sail to Europe on the Carmania.12 The ship departed New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departed Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. The men travelled first class; they enjoyed ship board leisure activities, including concerts featuring the violinist Albert Spalding. They also had Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, and, once they entered dangerous waters, they took turns on submarine watch.

Oxford and Grantham

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but would remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. Various explanations have been offered for the change of plans,13 but, whatever the reason, the men of the detachment made their peace with it and in retrospect recognized the benefits of R.F.C. training. Their British instructors, unlike those in the U.S., had had war flying experience, and this added considerable interest to the course work. Since the men had already covered much of the material being presented, they did not have to study especially hard, and they enjoyed Oxford hospitality and explored the town and surrounding countryside. Another American detachment had already started ground school at Oxford in September, so that the one that arrived in October came to be called the “second Oxford detachment.”

The men were eager to start learning to fly, but disappointment was in store for most of them at the end of four weeks. The R.F.C. was able to accommodate twenty men from the detachment at No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford in early November, but the others, including Shaw, set out on November 3, 1917, for Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend a machine gun course at Harrowby Camp.13a As Parr Hooper, also sent to Grantham, remarked: “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”14 The men spent the first two weeks of November learning about and practicing with the Vickers machine gun.

Waddington

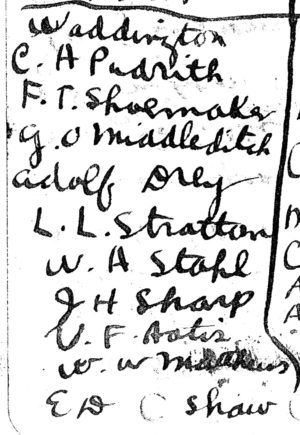

In mid-November, it was determined that there was room at training squadrons for fifty men, and Shaw was among those selected. Along with nine others (Adolf M. Drey, William Wyman Mathews, George Orrin Middleditch, Vincent Paul Oatis, Chester Albert Pudrith, Joseph Hiserodt Sharpe, Fred Trufant Shoemaker, Walter Andrew Stahl, and Lynn Lemuel Stratton), he set off on November 19, 1917, for Waddington (about twenty miles north of Grantham and just south of Lincoln), where several R.F.C. training squadrons were located.

There is little direct documentation of the early part of Shaw’s time at Waddington, but the log book and letters of Oatis are extant, and it is reasonable to assume that Shaw’s training resembled that of Oatis. The latter did not do any flying during his first two weeks at Waddington—perhaps because he and his fellow cadets were being given yet more ground instruction, or perhaps because of poor weather or a lack of planes.

Then, in his first letter home from Waddington, dated December 11, 1917, Oatis is delighted to report that he is finally flying: “It has taken a long long time to do it but we have finally killed the jinx. Last Tuesday we started flying and most of us are already soloing.” Oatis’s log book shows that late in the morning of Tuesday, December 4, 1917, he put in twenty-five minutes of dual flying in a DH.6 (a two-seat plane designed for training). Over the course of December and early January, Oatis, and presumably also Shaw, went up dual with instructors in R.E.8s and then also in B.E.2e’s (both were two-seater planes designed for reconnaissance and bombing) while also adding to their solo hours and practicing maneuvers in DH.6s.

In mid January 1918 second Oxford detachment member Walter Ludwig Deetjen was posted to Waddington, and he and Shaw evidently became friends. Both had presumably by this time completed their elementary training and were assigned to intermediate training squadrons at Waddington, where, as Deetjen noted, “there are [Training] Squadrons no. 44, 47, 48 and 51. There are Rumpties (Maurice Farmans) Martinsydes, R.E.8s, deH6’s, BE2E’s and deH4’s.”15

Deetjen first mentions Shaw in his diary on January 27, 1918, when they went from Waddington into Lincoln for the evening. By February 23, 1918, Deetjen had completed twenty hours solo flying, which meant he could be recommended for his commission. Shaw was evidently keeping pace; Pershing forwarded the recommendations for both Shaw and Deetjen to Washington in the same cable dated March 5, 1918.16 On February 24, 1918, Deetjen noted that “Barnard, who is now B Flt. Commander sent Shaw and myself up to fight. We went up in deH6’s and scrapped for 40 minutes. Molly’s engine was dud so I camped over him most of the time. But it was very wild and uncertain work. Once I nearly side slipped into him.”17

On February 27, 1918, Deetjen, and presumably Shaw, had his first experience of formation flying. Deetjen described how “at noon I went on my first formation. Major P [Lawrence Arthur Pattinson] led, I ran 2 and Shaw 3. We ran to Lincoln gaining height and then to Dunstan which we were supposed to annihilate. This tremendous task we accomplished by photography. If the honest inhabitants only knew the danger they were in. Pattinson dived 3 times and the first time Shaw and I both overshot his lead. We were supposed to remain 50 ft in rear and 50 above him. It was a 40 minute flip.”18

The next day:

Capt. Pryor called Molly Shaw and I [Deetjen] into his office to tell us we were on a formation reconnaissance to Grimsby at the mouth of the Humber. There we were to count the rolling stock and proceed to North Coates and photograph the road from there to the sea. We held much better formation today. It seemed much easier, and we also passed thru clouds, when I nearly lost all sight of No. 1. At Grimsby there were several sailing yachts in the harbor and from 3000 feet they looked prettier than anything I have yet witnessed from the air. Then running down the coast the breakers look like a long line of snow. A dark brownish colored storm was blowing in and rendered photography hard. Observation was poor also. We had lunch at 2:30 and in our frozen condition (it was very cold today) that lunch sure went home good.19

Around this time Deetjen and Oatis, and almost certainly Shaw as well, began flying dual with instructors in Armstrong Whitworth FK.8s in order to learn about stunting: loops, Immelmanns, stalls, and spins—maneuvers that could not be done in DH.6s.20 During this period, the cadets worked to pass various tests (height, cross-country, flying an operational plane, etc.) required for graduation from this stage of R.F.C. training—Deetjen passed the last of his tests on March 5, 1918, Oatis on March 24, 1918.21 After their graduation leaves, they were posted to No. 44 T.S. at Waddington, where they would start flying DH.4s; Shaw’s experience would have been similar, although I have not been able to determine the date of his R.F.C. graduation.

At the end of March 1918, Deetjen’s and Shaw’s commissions came through. The former wrote in his diary on March 29, 1918 that “Fearn had Molly Shaw, [Fred Trufant] Shoemaker, and I come to his office. Our commissions had come and we were sworn in then and there. So now I am once more an Officer—a 1st Lieutenant, Sig. R.C., A.S.”22

Four days later: “This morning Molly Shaw and I went down to Stamford (Easton drome) in Tinsydes. Saw the boys there of our detachment who were nearly as well fed up as we were.” Deetjen and Shaw were presumably flying Martinsyde G.102s—large single-seater aircraft. The following day, April 3, 1918, “at 1:30, with [Sidney Russell] Tipple leading, Molly and I went to take our deH4 formation and height test.”23

Pershing had forwarded the recommendation that Shaw and Deetjen be commissioned in early March; now, a month later, the commissions were nearly official. Deetjen wrote on April 4, 1918 that “This morning I got my Transfer Card and Log Book signed and then with Molly, two Canadians, and an English officer we went to see the Colonel of the 27th Wing. He passed us all. And now we are regular pilots and by the R.A.F. (which sprang into existence on April 1st, being the amalgamation of the R.N.A.S. and R.F.C.) rules we can wear wings. But by U.S. Regs., we have to wait till we are on Active Duty.” He continues: “In the afternoon Molly, Trench and I took the 3 160 Hp. Martinsydes and ran to Stamford, No. 5 T.D.S. . . . We arrived home at six o’clock, and found telegrams placing us on Active Duty. . . .”24 They also learned that they were ordered to report to No. 4 Auxiliary School of Aerial Gunnery at Marske-by-the-Sea the next day.

Marske

Shaw and Deetjen arrived at Marske in the North Riding of Yorkshire on Friday, April 5, 1918,

at 6 P.M., after traveling from 10:21 A.M., changing trains four times. We nearly lost our luggage twice and some of it came trailing in Saturday morning. The aerial distance is about 60 miles. Coaches were all crowded. Once 11 of us were in a compartment built for six. Gee this is a fine place. Small mess, mostly Canadian and American officers. Better food, greater variety, and more of it than at any other place yet. Here we are about 400 yards from the sea, and the bracing air and sunshine make us sleep and eat more than ever. . . . When Molly and I pulled in here we found the quarters new and clean. Two men in a room, spring beds, and white sheets. Really a joy since blankets and a hard cot. Two pillows also.25

The next day, Saturday, “Molly and I ran down to Middlesbrough and bought a bath, a shave, had our uniforms cleaned and bought identification discs in silver. The kind you wear around your wrist like a girl. In the evening we saw ‘Maid of the Mountains,’ by a good company, and got to bed at 1 A.M. . . .”26

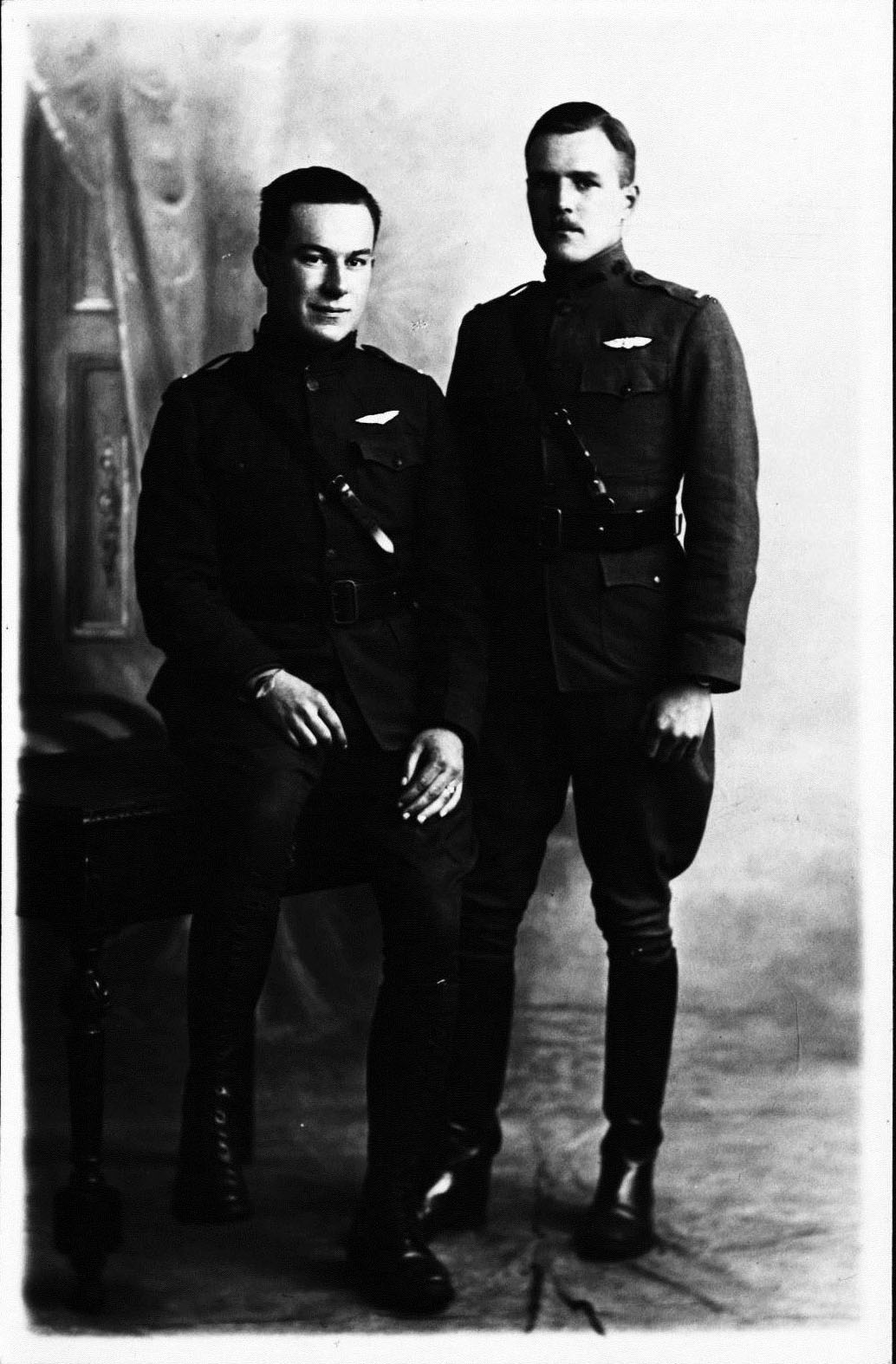

During the first week at Marske, the men were expected to do ground work, studying the Constantinesco-Colley synchronization gear (which timed a forward firing machine gun so that it did not hit a plane’s propellers) and the Vickers machine gun (again). It was just as well that they had class work, as the weather was poor. Shaw and Deetjen took advantage of time off to go into nearby Middlesbrough; they saw another play there (“Quinneys” by Horace Annesley Vachell) on Saturday, April 13, 1918, and also had their photo taken. The next morning, “found us cited in orders for an examination. It was Guns, C.C. Gear and sights. Mol ran up an average of 93% and I followed with 90%. We were transferred with others to ‘C’ group on the aerodrome and now await decent flying weather. It has been blowing and raining for eight days.”27 Trips to Saltburn-by-the-Sea and Middlesbrough provided a diversion. In both towns Shaw and Deetjen became acquainted with young women whom they took to dinner and shows; the return from Middlesbrough to Marske involved a somewhat unreliable late train.28

Finally, after rain, fog, and on one occasion, snow, the weather cleared on April 21, 1918, and they were able to began training on Bristol Fighters. The Bristol F.2B Fighter was a two-seater plane initially designed for reconnaissance but, with a powerful engine, also suitable for fighting. Deetjen describes his first flight, which he did solo and which involved target practice; that afternoon he “got a bus to play with” and concluded that it was “a regular little wonder.” While Deetjen was determined to continue on DH.4s, “Molly transferred to them [Bristol Fighters] at once.”29 It may be that Shaw simply preferred flying the Bristol Fighter, or he may, like many of his comrades, have wanted to fly a fighter plane operationally, rather than being assigned to a reconnaissance or bomber squadron. Apparently as a consequence of his decision, Shaw remained at Marske, while Deetjen was posted away: “On Monday afternoon [April 22, 1918] I [Deetjen] ran in to Middlesbrough and later met Molly there. We took the girls to dinner and then I saw Mol go back to Marske.” Deetjen proceeded to London and then Stonehenge to train as a bomber pilot.30

I find no documentation of Shaw’s activities over the next few weeks, but newspaper accounts state that he trained for a time in Scotland.31 This is not reflected in his very sketchy R.A.F. service record but is nonetheless possible: second Oxford detachment member John Marion Goad, also a Bristol Fighter pilot, apparently trained at Marske in April 1918 before going to Ayr and, presumably, the No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting, on the west coast of Scotland.32

Shaw is next documented as posted to the British pilots pool at No. 2 Aeroplane Supply Depot at Rang du Fliers south of Boulogne on May 26, 1918. Goad was posted there the same day, Deetjen four days later.33 The latter departed the evening of June 3, 1918, assigned to the recently created No. 104 Squadron R.A.F. / I.A.F.: “Of course Molly, Red [Frank Simpson Whiting], and the rest kidded the life out o’ me, claiming I was ‘cold meat’ since you usually are in a green outfit.”34

No. 48 Squadron R.A.F.

The next day, June 4, 1918, Shaw was assigned to No. 48 Squadron R.A.F.35 No. 48 had been flying Bristol F.2B Fighters since May of 1917. In the latter part of March 1918, during the first phase of the German Spring Offensive, No. 48 had had to move west from its base at Flez aerodrome, finally settling in at Bertangles, just north of Amiens, and it was at Bertangles that Shaw joined the squadron. 48 Squadron was part of the 22nd Wing (headquartered at Bertangles), which in turn was part of R.A.F. V Brigade, which supported the British Fourth Army36; the Fourth Army front extended approximately from Albert to Montdidier. No. 48 Squadron was involved in offensive and escort patrols, reconnaissance and photography, and also ground strafing and bombing.37

Many of No. 48 Squadron’s records were destroyed in a raid on the Bertangles aerodrome the night of August 24–25, 1918, so that much detail about Shaw’s activities with the squadron has been lost.38 Some information can, however, be reconstructed from other sources; Stewart K. Taylor’s account (“Uncompromising and Efficient”) of 48 Squadron pilot Harold Anthony Oaks in particular provides guidance.

Shaw was apparently assigned to A flight and teamed with observer Tom Walter Smith, a former accountancy student from Staffordshire who had joined the squadron at the end of May 1918.39 Within a week Shaw was crossing the lines. His first such flight, uneventful, probably occurred on June 9, 1918, the same morning that the Germans launched their Operation Gneisenau (also called the Battle of the Matz or the Montdidier Noyon Offensive), the penultimate push of their Spring Offensive.40

Just after 4:30 the next morning, June 10, 1918, six planes of 48 Squadron’s A flight, including that flown by Shaw with, presumably, observer Smith, took off from Bertangles and headed south towards Montdidier “to patrol the southern reaches of their front and keep any [sic] eye on the northern edge of the German advance.”41 At Montdidier flight commander Charles Ronald Steele led them across the lines and they turned east towards Roye.

Over Roye, at 5:45 a.m., as Steele recorded in his combat report, he “led the formation down on 6 D.5’s, which tried to escape by diving N.E. Four of my machines singled out the same E.A. putting into it about 1000 rounds in all, at an average range of 100–150 yards. The E.A. went down in a steep dive with smoke pouring from it which quickly changed to flames. When last seen the E.A. was diving through a cloud, still blazing.” Steele’s narrative was confirmed by Oaks, Shaw, and Harry Yarwood Lewis, “pilots in the same formation.”42 It appears that the victory credit for this Albatros D.V was shared by Steele, Oaks, Jack Elmer Drummond, and Frank Cecil Ransley, although in at least one instance Shaw and Lewis are also named.43 On returning to the aerodrome, Shaw “found a piece of shrapnel shell lodged in one of the wings of his airplane.”44

Five days after this patrol, on June 15, 1918, Goad joined No. 48 Squadron; another American, Bryan Mann Battey, had been assigned to the squadron in late May 1918.45 On the fifteenth, the three Americans and the Canadians officers then in 48 Squadron posed for a photo, a copy of which was kept by Lewis.46 Of himself and Goad (both assigned to C flight47) and Shaw, Battey later wrote that:

together we constituted an aerial circus that made our English fellows sit up and take notice. In very short order we were generally known as “the wild Yanks.” One of us that might be left upon the ground could always recognize the other “wild Yanks” long before they slipped down into the drome by a series of tricks that we always indulged in before landing, partly to put America “on the map” in our aerial sector and partly for the practice such stunts afford for real combat work.48

I find no information about Shaw specifically until early July, but there is some information about the activities of the squadron’s three flights. It is perhaps worth noting that, beginning about June 21, 1918, according to Taylor, 48 Squadron offensive patrols were to “be flown in strengths of not less than two flights,” a response to the report that they would now be encountering the formidable Fokker D.VIIs of Jagdgeschwader II.49 Shaw probably took part in one such mission on June 25, 1918, that apparently involved all three flights, but nevertheless resulted in casualties; and the next day he may have flown as part of the morning offensive patrol made up of A and C flights.50 It appears that A flight did not fly on June 27, 1918, the day that Goad and his observer failed to return.51 On June 29, 1918, A and C flights again flew a morning O.P. together, and the pilots probably included Shaw, as did presumably the O.P. of July 1, 1918, comprised of A and B flights.52

Shaw, flying with Smith as his observer, is documented as one of the A flight pilots on an O.P. made up of A and B flights led by Oaks and Drummond, respectively, on July 2, 1918. They set off in the early morning and flew east-southeast, reaching altitudes of 17 and 19,000 feet. Between Rosières-en-Santerre and Foucaucourt-en-Santerre, inside the bend the Somme makes at Peronne, they encountered and engaged three separate formations of enemy planes, with one decisive victory credited to Oaks at 7:45. Nearly an hour later, on the return journey, when they were once again near Foucaucourt and flying at about 16,000 feet, A flight encountered nine Pfalz scouts.53 In the narrative of his combat report, Oaks describes how “Two of my Pilots and myself, put in all about 500 rounds into an E.A. at short ranges (about 150–50 yards) and later the whole Flight saw an E.A. on the ground, about half a mile South of Soyecourt.” Oaks, Shaw, and Lewis were credited with one enemy plane destroyed.54

Flights of No. 48 Squadron, in conjunction with other squadrons from 22 Wing, undertook another O.P. the evening of that same day, described by Taylor as an effort “to clear out any EA they could find south of the River Somme.”55 Shaw and Smith, flying Bristol Fighter C808, took off with their flight at 6:25 p.m.; as in the morning, there were several engagements in the general vicinity of Foucaucourt. At some point during aerial combat, C808’s top left longeron and front petrol tank were shot through, but Shaw was able to pilot the plane back to Bertangles, where C808 landed at 8:25 p.m.56 The available documentation does not indicate whether Shaw and Smith returned with their flight or were forced to return early. Neither was injured, but the plane was sent to 2 A.S.D. for repairs.

In addition to offensive patrols, Shaw and Smith evidently flew reconnaissance patrols, some of which set out before 4 in the morning.57 Battey later recalled that “When ‘Molly’ was ordered to go back of the line fifteen miles on a dangerous reconnaissance he went back eighteen or twenty to bring in a better and more accurate report.” Some of these patrols were conducted by individual planes, some apparently in pairs, but also in larger numbers.58 Oaks led a flight of five planes on a reconnaissance from Bray to Rosière the evening of July 3, 1918, as well as a low dawn reconnaissance over Hamel-Lamotte and Albert the next morning; Shaw may well have taken part in one or both of these.59

Oaks, who had stepped in as A flight commander while Steele was on leave, left for England soon after Steele returned on July 4, 1918. Steele may well have led A flight, and Shaw, on missions daily over the next five day, but the only mission for which I find documentation is a late morning one on July 7, 1918, when Steele and his formation, returning from escorting DH.4s to Bray-sur-Somme, encountered and engaged eight Pfalz scouts.60

At 6 p.m. two days later, July 9, 1918, Shaw and Smith, flying Bristol Fighter B1113, set out from Bertangles on a single-plane long reconnaissance patrol; they failed to return.61 Writing to Shaw’s mother the next day, squadron commander Keith Rodney Park stated that “observers on the ground near our front line [told us] that they had seen one Bristol fighting its way back against three enemy scouts. [A]fter a long struggle the Bristol was seen to fall in pieces in the air.”62 According to the relevant casualty cards, “Battery reports wing of one BF machine folded during combat E of Albert.”63

German pilot Otto Könnecke of Jasta 5 apparently claimed a plane shot down northeast of Albert on July 9, 1918, (time unspecified) and it is possible that this was B1113.64

Afterwards

From newspaper accounts, it appears that Shaw’s family received a telegram on August 1, 1918, reporting that he was missing.65 Park’s letter apparently arrived soon thereafter, stating that “I would like to hold out some even small hopes but fear that would be unfair.” A letter from Battey dated July 13, 1918, in which he refers to Shaw’s “passing,” must have been received about the same time.66 On August 27, 1918, Shaw’s mother received the official telegram, dated that day, stating that her son had been killed in action.67 It is hard to imagine that anything could add to the family’s sorrow, but Mrs. Shaw received that same afternoon another telegram letting her know that Shaw’s friend Battey was missing in action.68 Also on August 27, 1918, Elliott White Springs, now with the U.S. 148th Aero, wrote his father in South Carolina that “E.D. Shaw of Sumter has been missing some time. If you know his people you might write them a letter of sympathy. There’s a good chance that he may be alive and a prisoner. Fine fellow. We came over together.”69 It is evident from the elder Springs’s letter to Shaw’s father, reproduced in The State (Columbia, S.C.), that he had learned that Shaw had not survived.70

An undated notation on Shaw’s casualty card records that “Report from B. M. Mission states that [Shaw] was brought down dead southeast of the village of Grancourt” and that he “was buried in the ‘square’ 1620/19b.”71 “B. M. Mission” presumably refers to the post-war British Military Mission in Berlin, whose remit included locating the missing and dead; the map “square” reference is of the type used on German military maps.72 It specifies a location about a half mile south-southeast of Grandcourt (Somme)73 that matches the location specified (Map 57D R 16) by a burial return form documenting the site from which Shaw and Smith were exhumed in early 1919 by a Canadian burial party.74 The burial return notes a “disc” apparently associated with Shaw’s body; it is possible that this was the same silver disc that Shaw acquired in early April while stationed at Marske. If so, it would have helped with identification, although the burial return suggests that identification came from knowledge of the number of the plane.

According to an additional burial return document associated with Shaw, his remains were initially “transferred in error to Aisne-Marne American Cemet[ery], Belleau” by the American Graves Registrations Services before being returned to Regina Trench Cemetery for “reburial in the same grave with . . . Smith.”75 Shaw is the only American buried in this cemetery, which is located about halfway between Grandcourt and Courcelette and not far from where Shaw and Smith were originally buried.76 Why Shaw did not find a final resting place in an American cemetery and why he and Smith were buried in the same grave remain open questions. Shaw’s burial file, which is presumably at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, may provide answers; I have not yet been able to consult it.

In late 1919 Claire Oberst, who had been with Shaw at O.S.U., Oxford, and Grantham, travelled from Ohio to South Carolina to pay his respects to Shaw’s parents; “He characterized Shaw as one of the best flyers that American had developed during the war.”77 At some point a cenotaph commemorating Shaw was erected in the Shaw family lot in Sumter Cemetery.78 In 1941 a training airfield near Sumter was named for Shaw; in 1947 it became Shaw Air Force Base.79

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Shaw’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Ervin David Shaw. Shaw’s R.A.F. service record gives his birth date as September 30, 1894; see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Erwin [sic] David Shaw. Snowden, ed., History of South Carolina, vol. 5, p. 252, gives September 13, 1894. As South Carolina did not issue birth certificates during this period, I find no means of verifying which date is correct. Shaw’s place and date of death are taken from “Shaw, E.D.” The photo is a detail from a group photo of Shaw’s O.S.U. ground school class.

2 See “Ervin David Shaw (1894 – 1918)” and Thomas Shaw, “John Patrick Shaw (1750 – 1810)”; these are both entries in a WikiTree maintained by various people.

3 See Parker, Aldermans in America, passim, and particularly pp. 11, 43, 148, and 605–06.

4 See article on David Charles Shaw on p. 252 of Snowden’s History of South Carolina, vol. 5. There is an engaging photo from 1906 of the Shaw family in their new Buick with a very young Ervin David Shaw driving while his father, holding his (at the time) youngest child, looks on. It can be seen at Ervin Shaw, “Martha Priscilla Shaw.”

5 “Personal.”

6 Shaw’s name appears regularly in Sumter’s two newspapers, the Sumter Daily Item and the Watchman and Southron, but with no reference Davidson or any other educational institution after December 1912 until mentions of attendance at Davidson and Georgia Tech in August 1918 obituaries; see, for example, “‘Bob’ Purdy Dead on French Front.” I have not been able otherwise to document Shaw’s association with the Georgia Institute of Technology; this may reflect inadequate access to records or, more likely, I believe, that the obituaries were mistaken but became the source for later biographies.

7 R.A.F. service record cited above.

8 See, for example, an advertisement for Buicks on p. 6 of the Sumter Daily Item of July 8, 1914. And see “Auto Races New Year’s Day.”

9 See Shaw’s draft registration, cited above.

10 See brief, untitled article on p. 5 of the Watchman and Southron of June 30, 1917.

11 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

12 See brief, untitled article on p. 7 of the Watchman and Southron of September 15, 1917.

13 See, for example, the explanations supplied by Hamilton Hadley on p. 4 (286) of “Foreign Aviation Detachments,” by Geoffrey Dwyer on p. 2 of “Report on Air Service Flying Training Department in England,” and by Claude E. Duncan as recorded in Sloan and Hocutt, “The Real Italian Detachment,” p. 44.

13a There are at least two group photos of cadets at Grantham that include Shaw. One is reproduced in Way, “Ervin Shaw’s Love Affair with Fying Begins”; another in Way, “Ervin David Shaw Makes his Final Flight,” as well as by Pettigrew on his web page for Shaw at Sumter / Edmunds High School. In the latter photo, I believe Shaw is flanked by Earl William Sweeney (on his right) and Edward Addison Griffiths (on his left).

14 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

15 Deetjen, diary entry for January 18, 1918.

16 Cablegram 678-S. There was always a considerable delay between completion of requirements and Pershing’s cables. There would be another wait for the response from Washington, then for this to trickle down to the training squadron level, and finally, another few days before a newly-commissioned officer was placed on active duty.

17 Barnard was probably Franklyn Leslie Barnard, whose R.A.F. service record puts him at Waddington as an instructor in early 1918. See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Franklyn Leslie Barnard.

18 Deetjen, diary entry for February 28, 1918.

19 Deetjen, diary entry for February 28, 1918. Pryor was probably Arthur Deen Pryor; for his rank as captain, see relevant entries at Pentland, Royal Flying Corps; for his presence at Waddington, see Mick Davis’s listings for DH.6s A9661, A9758, and A9759 at “De Havilland 6.”

20 Oatis, Pilot’s flying log book, entry for February 15, 1918; Deetjen diary entry for February 28, 1918.

21 Deetjen, diary entry for March 5, 1918; Oatis, Pilot’s flying log book, entry for March 24, 1918.

22 Fearn was probably Irving Kohrs Fearn, who had sailed with, i.a., Gustav Kissel, to Europe in July 1917; see Douglas Campbell, Let’s Go Where the Action is!, pp. 86-7. (Deetjen, for reasons too complicated to go into here, had previously been commissioned but relinquished the rank; thus he was now “once more an Officer.”)

23 Deetjen, diary entry for April 3, 1918.

24 Trench was probably Walter Frederick Oliver Trench, who was at No. 44 T.S. at this time; see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Walter Frederick Oliver Trench.

25 Deetjen, diary entries for April 7 and 8, 1918.

26 Deetjen, diary entry for April 8, 1918.

27 Deetjen, diary entry for April 15, 1918.

28 Deetjen, diary entries for April 15, 17, 20, and 21, 1918.

29 Deetjen, diary entry for April 21, 1918.

30 Deetjen, diary entry for April 24, 1918.

31 See, for example, “Sumter’s First Sacrifice,” which states that Shaw “completed his training at Oxford and in Scotland.”

32 See Deetjen, diary entry for April 8, 1918.

33 See their respective casualty forms: “Lieut. Ervin David Shaw U.S.A.S.,” “Lieut. John Marion Goad U.S.A.S,” and “Lieut. W L Deetjen USAS.”

34 Deetjen, diary entry for June 5, 1918

35 See Shaw’s casualty form, cited above.

36 Numbers for RAF brigades normally corresponded to the number of the army they served. However, the Fifth Army was renamed the Fourth Army on April 2, 1918, in the wake of Rawlinson’s replacing Gough; see Edmonds, Military Operations in France and Belgium 1918, vol. 2, pp. 27–28 and 109.

37 Wikipedia, “No. 48 Squadron RAF.”; Bailey and Chamberlain, “No. 48 Squadron RFC/RAF,” pp. 118–20.

38 On the raid, see Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 480; Taylor, “Uncompromising and Efficient,” pt. 2, pp. 256–58; and Robertson, “No. 48 (General Reconnaissance) Squadron,” p. d. Robertson indicates that the records were destroyed.

39 See Taylor, “Uncompromising and Efficient,” pt. 1, p. 196, regarding Shaw’s flight assignment and observer; see caption to photo on p. 194 for the identity of the observer. On Smith, see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Tom Walter Smith, and The National Archives (United Kingdom), Airmen’s Records, record for Tom Walter Smith.

40 Regarding this flight, see “Local Matters,” which summarizes a letter Shaw apparently wrote on June 11, 1918.

41 Taylor, “Uncompromising and Efficient,” pt. 1, p. 196

42 There is a copy of Steele’s combat report in “Sqn. No. 48, RFC/RAF, 1917 – 1918 Squadron Record Book.” I was not able to locate his combat report at the National Archives (UK). NB: Secondary sources (e.g., Shores, Frank, and Guest, Above the Trenches, entries for Oaks, Steele, Drummond, and Ransley) give the time of this combat as 17:45. Stewart K. Taylor’s account in “Uncompromising and Efficient,” p. 196, presumably based on documents provided by Oaks, confirms the a.m. time given in Steele’s combat report.

43 See Shore et al., cited above, entries for Oaks, Ransley, and Steele; the entry for Drummond also includes Lewis and Shaw. In a letter of July 10, 1918, to Shaw’s mother, squadron C.O. Park wrote of Shaw that “He shot down two enemy scouts,” which suggests that Shaw (should have) received credit for the E.A. on June 10, 1918. Park’s letter is reproduced in “Lieuts. Purdy and Shaw.”

44 “Local Matters.”

45 See “Lieut. John Marion Goad U.S.A.S.” Bailey and Chamberlain, “No. 48 Squadron RFC/RAF,” p. 125, indicate that Battey arrived on May 26, 1918; see also Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 34 [226]. Battey’s casualty form is among those at the beginning of the alphabet that have not been preserved; see “About” at Officer’s Casualty Forms of the Royal Flying Corps & Royal Air Force.

46 Reproduced on p. 201 of Taylor, “Uncompromising and Efficient,” pt.1.

47 On their flight assignment see “Body of Lieut. John M. Goad Found”

48 Battey, in a letter quoted in “Body of Lieut. John M. Goad Found.”

49 See Taylor, “Uncompromising and Efficient,” pt. 1, pp. 197–98.

50 Ibid., pp. 198–99.

51 Ibid., p. 199.

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid., pp. 199–200.

54 See Oaks’s combat report in Air combat reports: 48 Squadron Royal Air Force, July 1918; neither the plane numbers nor the names of Lewis’s and Shaw’s observers are given.

55 Taylor, “Uncompromising and Efficient,” pt. 1, p. 200.

56 See the casualty report in The National Archives (United Kingdom), Reports on aeroplane and personnel casualties, 01 July 1918 – 10 July 1918.

57 See the operations orders issued by squadron C.O. Park for June 21, 1918, transcribed in Taylor, “Uncompromising and Efficient,” pt. 1, p. 198.

58 Ibid.

59 Taylor, “Uncompromising and Efficient,” pt. 1, p. 201.

60 See his combat report in Air combat reports: 48 Squadron Royal Air Force, July 1918.

61 See the letters from Park and Battey reproduced in “Lieuts. Purdy and Shaw” on the nature of the mission.

62 Park’s letter, reproduced in “Lieuts. Purdy and Shaw.”

63 “Shaw, E.D.”; “Smith, T.W. (Tom Walter).”

64 Bailey and Chamberlain, “No. 48 Squadron RFC/RAF,” p. 122, state that “there is no corresponding German claim.” Presumably new information prompted the matching of a “Dolphin” shot down by Könnecke on July 9, 1918, with B1113 in Franks, Bailey, and Duiven’s The Jasta War Chronology. The entry for Otto Könnecke at The Aerodrome Forum, credits him with a “Bristol F.2b NE of Albert” on July 9, 1918. Without access to (the uncited) original sources, I cannot evaluate these last two.

65 “Purdy and Shaw Fallen.”

66 Battey’s letter reproduced, along with Park’s, in “Lieuts. Purdy and Shaw.”

67 “Killed in Action.” The telegram is reproduced at the web page for Shaw at Pettigrew’s Sumter / Edmunds High School Sumter.

68 Ibid.

69 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 213. And see the entry in War Birds for August 27, 1918: “Read is dead and so is Molly Shaw” (Read may refer to Francis Kinloch Read, wounded, not killed, seven days before Shaw, or Richard Brumbach Reed, killed in a training accident at Turnberry June 5, 1918)

70 “Pays High Tribute to Flying Comrade.”

71 “Shaw, E.D.”

72 I am grateful to members of The Great War Forum for this information. See ‘Map help: “ ‘square’ 1620/19 b”.’

73 See the telegram from Gorrell to Lippincott et al. dated April 28, 1919, in Hamilton, World War One Burial File, regarding information about Hamilton and Shaw received from the Berlin Central Records, with the identification of “Grancourt” as “Grandcourt near Meraumont [sic; sc. Miraumont] region Peronne.”

74 The burial return is reproduced at “Serjeant Tom Walter Smith” and at “1st Lieutenant Ervin David Shaw,” the Commonwealth War Graves Commission web pages for Smith and Shaw.

75 Burial return reproduced at “1st Lieutenant Ervin David Shaw.”

76 See information about Regina Trench Cemetery at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission web site.

77 “Personal News.”

78 See photos at Ervin Shaw, “Lieut Ervin David ‘Molly’ Shaw.”

79 Wikipedia, “Shaw Air Force Base.”