(Southampton, New York, November 24, 1893–December 21, 1970, Palmetto, Florida).1

Training in England ✯ 11th Aero, St. Mihiel ✯ From Amanty to Maulan ✯ The Meuse–Argonne Offensive

The Porters were among the early settlers of Massachusetts and, several generations later, among those who established the first permanent settlement by U.S. citizens in what was then the Northwest Territory. Amos Porter, Jr., Robert Brewster Porter’s great-great-grandfather, was one of the forty-eight pioneers who in 1788 arrived at the confluence of the Ohio and Muskingum Rivers and founded the town of Marietta there. 2

Robert Brewster Porter’s father, Finley Robertson Porter, was born in Lowell, a few miles north of Marietta, but his family relocated to Virginia when he was quite young. His widowed mother then settled on Long Island, where Robert Brewster Porter, the only child of his father’s marriage to Lydia Brewster, was born; Lydia died when her son was two.3 For a time young Porter apparently resided with his paternal grandmother and aunt.4 His father remarried in 1902, and the 1910 census shows the family, including Robert Brewster Porter and two half-sisters, residing in Hamilton, New Jersey, where their father worked as an engineer for an oilcloth company.5 Porter entered Princeton the following year with the class of 1915, but completed only his freshman year.6 His father, meanwhile, became chief engineer with the Mercer Automobile Company, and then, in 1914, founded his own Finley Robertson Porter (automobile) Company at Port Jefferson on Long Island. Robert Brewster Porter served as the company’s treasurer, and worked as a draftsman.7 In 1916 he is recorded as a student at Towne Scientific School of the University of Pennsylvania, with no indication of whether he took a degree.8 When he registered for the draft in early June of the following year, Porter described himself as an engineer in his father’s company.9

Around the same time Porter evidently applied for the aviation service; a notice in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on June 8, 1917, reports that he had “received instructions from the War Department to report for examination as a first lieutenant in the Aerial Officers Reserve Corps in the signal service at Mineola.”10 Having passed the requisite exams, he was sent to the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University to attend ground school; he and his class of twenty-seven men graduated September 1, 1917.11 All but three of the graduates chose or were chosen to do their advanced training in Italy. Porter was soon back in Mineola, part of a detachment awaiting orders to sail, which they did on September 18, 1917. They boarded the Carmania at a Cunard pier in the Hudson River and sailed initially to Halifax. From there, on September 21, 1917, the Carmania set out as part of a convoy to cross the Atlantic. The 150 men of the detachment, travelling first class, had plenty of leisure, apart from submarine duty towards the end of the voyage and daily Italian lessons conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them.

Training in England

It was thus a surprise when, on docking at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the members of the “Italian detachment” learned that they would not continue to Italy, but would remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford. There was some grumbling, but the men fairly quickly settled into rooms at Christ Church College and The Queen’s College and began to enjoy life at Oxford. Porter palled around with his O.S.U. ground school classmates Fremont Cutler Foss and Albert Frank Everett, dining with them at Buol’s on Sunday of the week of their arrival and a taking bicycle ride to Dorchester-on-Thames with them two weeks later.12

After a month, on November 3, 1917, twenty men from the detachment learned they would start flying training at Stamford, but the others, including Porter, were sent north for a machine gunnery course at Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire. As Parr Hooper, also ordered to Grantham, remarked, “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”13 For two weeks the men learned about and practiced on the Vickers machine gun. In mid-November fifty men departed for squadrons when that number of training places opened up, but Porter was among those who remained at Grantham for another two-week course, this time on the Lewis machine gun.14 The cadets continued at Grantham through the end of November. Thanksgiving, celebrated with football and an elaborate dinner, was the highlight of their time there. The football game pitted the “Unfits” against the “Hardly Ables”; Porter, along with Charles Carvel Fleet, was a substitute on the winning Unfits team.15

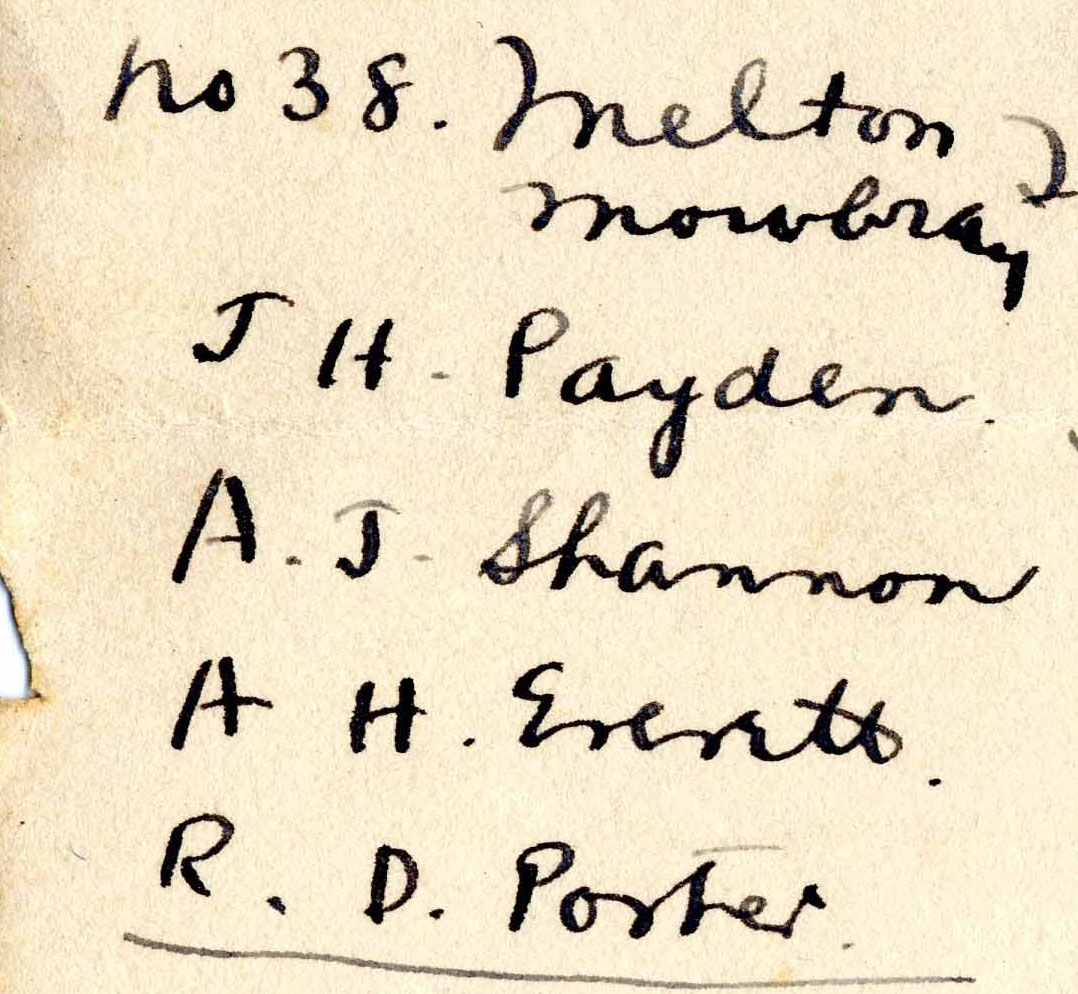

Finally, on December 3, 1917, the men still at Grantham were assigned to squadrons. A small group consisting of Porter, Everett, Joseph Raymond Payden, and Andrew Joseph Shannon was sent to No. 38 Squadron, a home defense squadron tasked with defending the West Midlands from Zeppelins.16 At the end of 1917, the squadron was flying F.E.2b’s and F.E.2d’s, two-seat fighter and bomber biplanes—not suitable for primary flight training, but the cadets could certainly have gone up as passengers. Headquartered at Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire, the squadron’s three flights operated out of Leadenham, Buckminster, and Stamford.17 Payden kept memorabilia that link him to Stamford during this period, and, given that Porter, shortly after the war, married a woman from Stamford, it is likely that he also did some of his training there.18

By late March 1918 Porter had progressed sufficiently—there is unfortunately no record of his postings—to be recommended for his commission as a first lieutenant. Pershing’s cable to Washington forwarding the recommendation is dated April 1, 1918, the same day that the Royal Flying Corps became the Royal Air Force; the cable belatedly confirming the appointment is dated May 13, 1918.19

A letter written by Fleet indicates that by the end of May 1918 Porter, along with his O.S.U. ground school classmates Pryor Richardson Perkins and Albert Sidney Woolfolk, as well as Hilary Baker Rex, was at No. 5 Training Squadron at Wyton (about fifteen miles northwest of Cambridge), where Fleet would join them.20 It would have been clear by now that all of these men were being trained to fly two-seater reconnaissance and bombing planes; all would be assigned to American squadrons flying DH-4s. There is some evidence that pilots at Wyton flew DH.4s (the British version of the DH-4): Guy Brown Wiser recalled that “The DH-4 [sic] . . . was used as a graduation test at Wyton Base, Huntingdon, England . . . .”21 However, aviation historian Guy Sturtivant records only DH.9s at 5 T.S.22 Furthermore, it is clear from Perkins’s log book that he did not fly on a DH.4 at Wyton, only DH.9s and DH.9A’s, and this may have been true also for Porter. The DH.9 was based on the DH.4, so the transition from one to the other would presumably not have been difficult—and perhaps welcome, as, despite hopes that it would be an improvement, the DH.9 proved inferior in performance to the DH.4.

In early July 1918 Porter was one of a large group of pilots ordered to travel from London to the American 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun in the Loire region of central France.23 Some of these pilots then proceeded to the 2nd A.I.C. at Tours, about seventy miles northwest of Issoudun, for further work at the School of Observation Training, while others, probably including Porter, did their next and final stage of training at the bombing school at the 7th A.I.C. at Clermont-Ferrand, about ninety miles southeast of Issoudun. In any case, Porter probably had the opportunity during his first two months in France to acquaint himself with the DH-4.

11th Aero, St. Mihiel

Porter, according to the roster of officers of the 11th Aero Squadron appended to the squadron’s history in Edgar Stanley Gorrell’s History of the American Expeditionary Forces Air Service, 1917 – 1919, was among a group of pilots and observers who reported to the 11th Aero at Amanty on September 12, 1918, the opening day of the St. Mihiel Offensive; the list also includes second Oxford detachment members Vincent Paul Oatis, Fred Trufant Shoemaker, and Walter Andrew Stahl.24 Other sources indicate that this influx of manpower occurred on September 9, 1918. Gerald C. Thomas, Jr., in The First Team, cites documentation indicating that on September 9, 1918, twenty-nine observers and pilots from Clermont-Ferrand arrived at Amanty to join the 11th Aero Squadron.25 The squadron history published in 1922 remarks that “It was on the afternoon and evening of September 9, 1918, that the squadron was brought up to its full strength by the addition of new pilots and observers,”26 and John Cowperthwaite Tyler, who was assigned to the 11th and had been at Amanty since the 6th, wrote in his diary on September 9, 1918, that “In evening whole mob of new pilots arrived.”27

The field at Amanty, about twenty-five miles south of St. Mihiel and the front, was shared at this time by the 11th, the 20th, and the 96th Aero Squadrons, the last-named being the only operational American bombing squadron up to this point. Although instructions for daylight bombing were drawn up in the course of August, it wasn’t until September 10, 1918, that the three squadrons became the First Day Bombardment Group.28

By this time the newly-established American First Army was completing preparations for the St. Mihiel Offensive in which the First Army, with assistance from the Allies, would seek to wipe out the German held salient that jutted southwest from the Allied line to encompass the town of St. Mihiel on the east bank of the Meuse River. It had been hoped that the attack could begin before the autumn rains, but it was delayed from the 7th until the 12th, and, in any case, the rains came early.29 Soggy ground meant that Porter and the other pilots and observers recently arrived at the 11th Aero did not have an opportunity to try out their planes or to get to know the terrain.30 Tyler wrote in his diary on September 11, 1918: “New bunch very anxious to fly, but no chance. . . . Kind of wild rumors of their putting us to work without any chance to fly together or get used to these machines.”

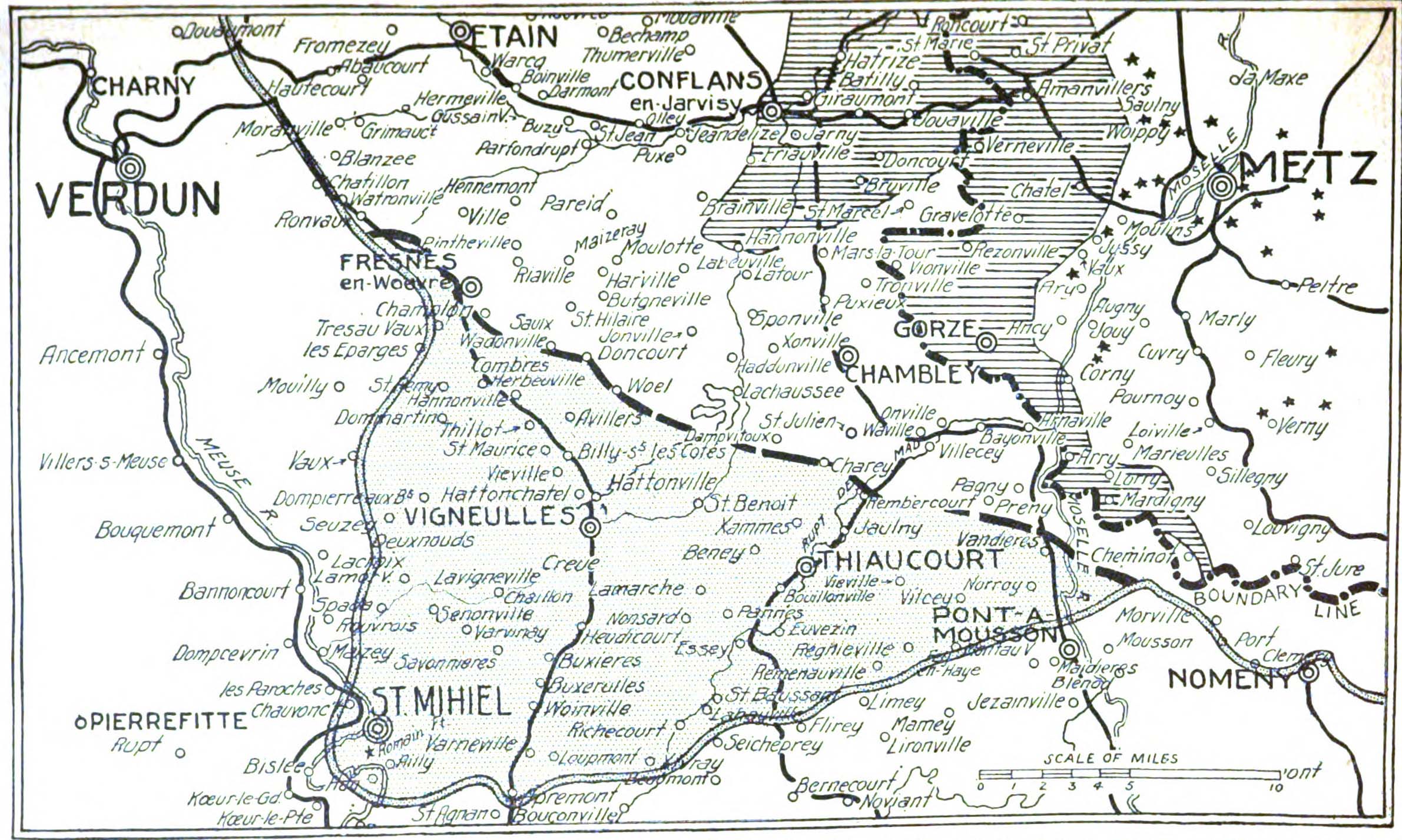

On the first two days of the St. Mihiel Offensive, September 12 and 13, 1918, planes and pilots of the 11th (and 20th) Aero were tasked with duties more appropriate to observation and pursuit squadrons.31 Four planes with their crews were detached and sent to Maulan, twenty miles west northwest of Amanty, “to be held ready to execute any missions given.”32 Otherwise, while the 96th Aero carried out bombing raids, the 11th and 20th Aero Squadrons—whose DH-4s were not yet properly outfitted for bombing—were on September 12 and 13, 1918, “subject to the orders of the Group Commanders, 2nd Pursuit Group for cooperation on the barrage patrols of the sector assigned to that Group.”33 The planes of the 2nd Pursuit Group (the 13th, 22nd, 49th, and 139th Aero Squadrons), flying Spads out of Gengoult Airfield northeast of Toul, were to “maintain a double tier barrage over the eastern sector of the [1st Pursuit] wing from day-break to dark.”34 “The purpose of this barrage is to create an area 5 kilometers in front of our advancing lines in which it will be safe for our army corps observation aviation to work.”35 Barrage patrol planes were to shoot down any enemy balloons and planes that might enter this area.36 The “eastern sector” to be covered was a roughly diamond-shaped area centered on Pont-à-Mousson on the Moselle, and defined by a western line running from Flirey northeast to Arnaville and a longer eastern line running from Nancy, in the south, northeast to Solgne.37 The role of the DH-4s of the 11th and 20th Squadrons during these missions was to fly at and to protect the rear of the pursuit plane formations.38

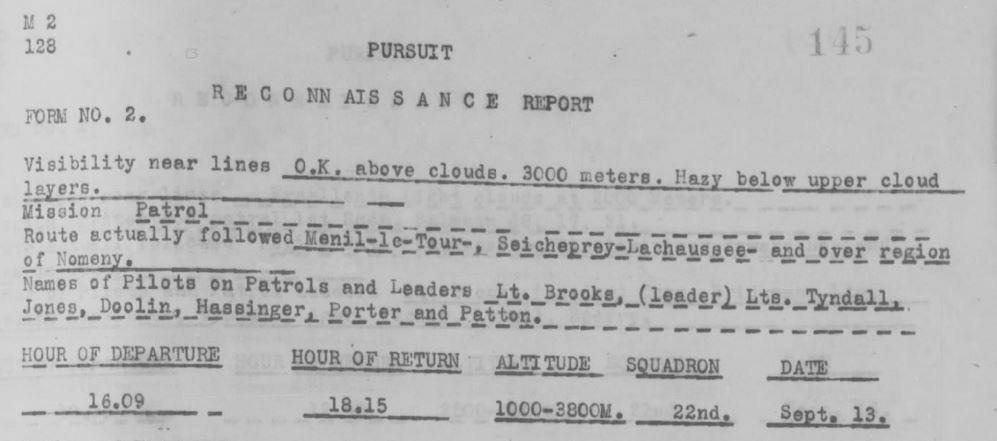

On September 12, 1918, one DH-4 from the 11th Aero flew with a formation of six Spads of the 49th Aero early in the afternoon on a patrol that took in Pont-à-Mousson on the Moselle River and flew west over Thiaucourt to Monsec, slightly to the northwest of the defined sector. Late the next afternoon, a plane from the 11th, along with one from the 20th, accompanied seven Spads from the 49th on a patrol from Pont à Mousson to Thiaucourt, while another flew with four Spads from the 22nd Aero over Nomeny (east of Pont-à-Mousson) and then over Lachaussée (north of Thiaucourt, thus again beyond the defined sector).39

The available records do not identify the crew of the 11th Aero’s DH-4 flying protection for the 49th Aero on the 12th, leaving open the possibility that it was Porter and an observer. It was not, however, Porter flying with the 49th late the next afternoon, as the records of the 22nd Aero show him and observer James Longstreet Patten accompanying the Spads of the 22nd Aero on the Nomeny–Lachausée flight around the same time.40

The outcome of these three documented flights involving the 11th Aero was, according to the records of the 2nd Pursuit Group, either “No aerial activity” or “Nothing to report.”41 It was fortunate for the 11th that none of these missions involved encounters with enemy aircraft, as it soon became apparent that DH-4s were not suited to “this fool Spad protection,” as Tyler called it.42 Arthur Raymond Brooks of the 22nd Aero, in his history of the squadron, noted that “At high altitude these ships [DH-4s] were good rear protection, but near the earth the Spads ran away from them, so they were impractical for our work.”43 Members of the 11th Aero would later write much more bluntly that “it took two days of that sort of patrolling before the powers that were discovered the absurdity of their plan. The only thing that prevented a terrific toll of ‘DH’ pilots and observers during those two days was the fact that there were so many Allied planes in the air over the St. Mihiel salient that the Hun did not venture very near the American lines.”44

The 11th began bombing operations the morning of September 14th,” but it was a near thing.45 Tyler, who led the 11th Aero’s first mission that day, wrote in his diary: “Bombs just arrived at midnight and no one knew how to put them on.”46 Porter in DH-4 No. 521 with Patten—who would be his observer on all but one mission—was assigned to the 11th’s afternoon mission that day, when ten planes from the 11th set out but returned without dropping their bombs.47

The next day Porter and Patten were once again assigned to the afternoon mission. The target was Longuyon, a good sixty-one miles north of Amanty. Howard Grant Rath’s account of the First Day Bombardment Group’s operations lists twelve DH-4s in the 11th Aero’s flight (the 11th’s raid report indicates nine) and states that “not all of these planes reached the objective.”48 Sigbert A. G. Norris’s narrative history of the squadron, however, reports that “All teams reached the objective and bombed at a height of 14,000 feet.”49 The conflicting sources mean it is particularly regrettable that Porter’s log book is not extant.

On September 16, 1918, the First Day Bombardment Group flew three missions. Porter and Patten took part in the second and third, both of which targeted Conflans-en-Jarnisy. Rath noted in his diary that on the second mission, while some planes from the 96th and 20th crossed the lines and dropped their bombs, “The 11th didn’t go over the lines even to drop their bombs. Brought them back home. The major [James Leo Dunsworth] sure was sore.” Visibility was good this day, so weather does not explain this failure. However, Rath’s and Tyler’s diaries make clear that inexperience, inadequate training and equipment, and unrealistic expectations were significant issues for the First Day Bombardment Group during this period. Rath provides an exasperated account of trying to get the three squadrons to coordinate their take offs for the third mission on the 16th, when the 11th set out prematurely, leaving the 96th scrambling to catch up. The squadrons were “all to follow the same route and keep in sight of each other and protect each other,” but plans and practice diverged. “The 11th came back and reported that they circled around before they went across [the lines]. 4 of them finally went across & bombed Conflans but their bombs fell short of the objective.”50 The records do not indicate which these four planes were; Norris’s narrative account for the 11th Aero states that “Nine machines left field . . . Six teams reached the objective and bombed. . . . Formation returned safely to field at 19:00 o’clock.”51 In this they were far more fortunate than the 96th Aero; four planes returned early, but the other four did not return at all on this, the last day of the St. Mihiel Offensive.

The First Day Bombardment Group as a whole was not ordered out on the 17th. Rath noted that “The weather was worse than ever today. . . . We wait for orders but thank the Lord none come in. The Americans seem to have taken all they want at present—the St. Mihiel ‘hernia’ has been completely wiped out.”52 Nevertheless, planes from the 11th Aero “left field on bombing mission with Conflans as the objective, at 11:05 o’clock. Our planes were used as protection planes on this mission. . . . All machines returned safely at 12:45 o’clock.”53 Neither the squadron’s narrative history nor its raid report specify how many planes took part in this mission, much less who the crews were, so that it is not known whether Porter flew this day.

The next day, September 18, 1918, was even more disastrous for the 11th than the 16th had been for the 96th Aero. Late in a day of extremely inclement weather, ten planes from the 11th Aero were ordered out on a bombing mission; four returned prematurely, and five, including that piloted by the squadron’s commanding officer, did not return at all. Only Oatis and his observer Ramon Hollister Guthrie completed the mission and returned safely. It had been assumed that the weather would preclude flying missions on this day, and a number of pilots who might have flown were sent instead to Colombey-les-Belles to bring back new planes: this may account for Porter’s not having been assigned to the raid.54

From Amanty to Maulan

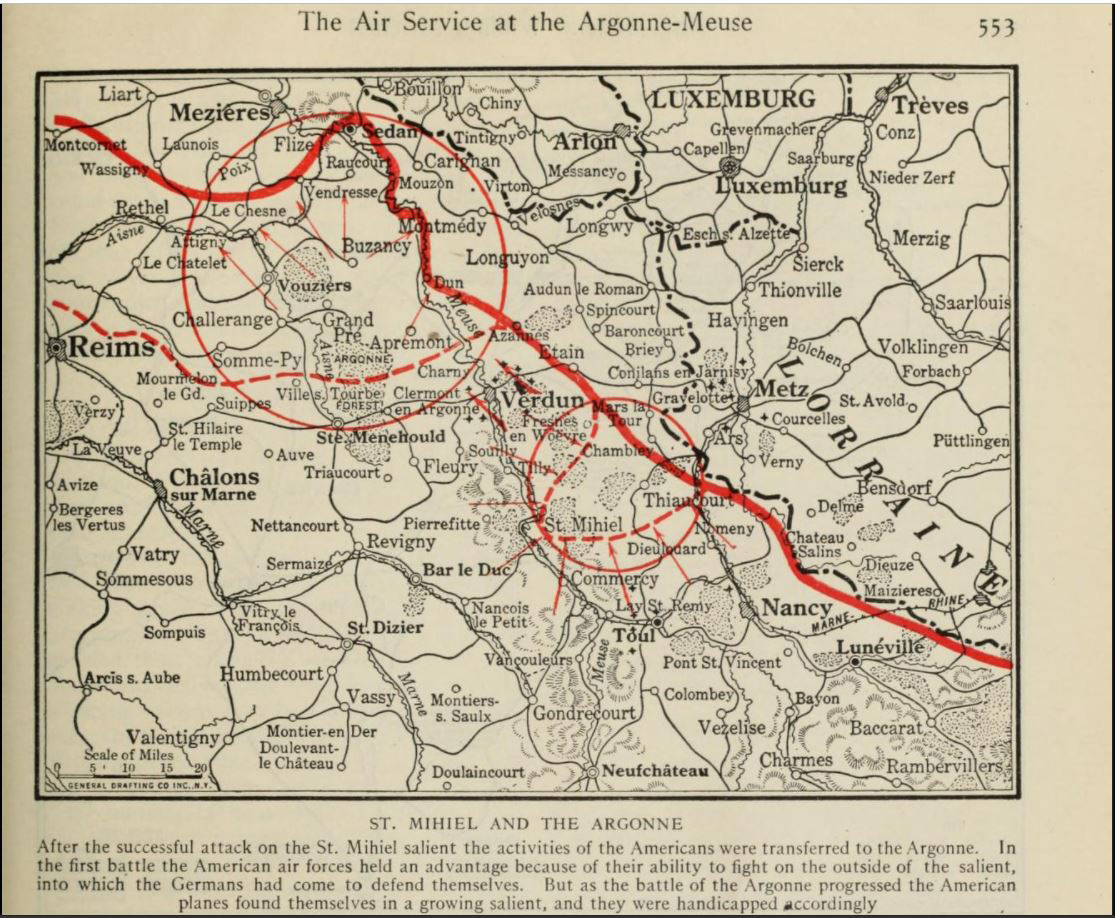

No missions were flown by squadrons of the First Day Bombardment Group from September 19 through September 25, 1918. On September 24–25, 1918, the squadrons were relocated—unobtrusively, as the change of fronts was to be accomplished without alerting the Germans—from Amanty to Maulan, that is, from the St. Mihiel to the Meuse-Argonne front; they were joined at Maulan by the not-yet-operational 166th Aero.

During the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the squadrons of the First Day Bombardment Group would be tasked with attacking “concentrations of enemy troops, convoys and aviation, railroad stations, command posts and [ammunition] dumps.”55 It was planned that railroad centers such as those at Stenay and Montmédy would be bombed early on, but this proved unrealistic, and they did not become targets of the First Day Bombardment Group until November. A second list of targets, concentrated in an area approximately fifty miles due north of Maulan, proved feasible and included Grandpré, Saint Juvin, Briqueney, Dun-sur-Meuse, and Doulcon; these were locations of German “Dumps, Railheads, Camps & Command Posts.”56

Just before the move from Amanty to Maulan, new pilots were assigned to the 11th, including Dana Edmund Coates, Ralf Andrews Crookston, Charles Louis Heater, and George Dana Spear from the second Oxford detachment and Alfred Clapp Cooper of the first Oxford detachment, as well as William Wallace Waring; Uel Thomas McCurry, of the second Oxford detachment, would arrive soon after the move to Maulan. Of these men, only McCurry and Heater had had operational experience.57 Heater’s, with No. 55 Squadron R.A.F., was extensive and warranted his being appointed the squadron’s new commanding officer.

Heater lectured the remaining and new pilots of the 11th Aero “on the primary importance of close, tight formations and also my confidence in the D.H.4, although I had not flown one with a Liberty motor.”58 He had them watch as he put a D.H.-4 through its paces, and when weather permitted he had them practice formation flying. Meanwhile, there was consultation among squadron leaders and higher-ups that led to the decision to fly larger formations over the lines—twelve to eighteen planes, combining planes from more than one squadron as needed to make up a flight.59 The 1922 squadron history describes “the reconstruction of a broken outfit and its complete transformation into a high grade, competent unit, confident of its ability and proud of its record.”60

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive

Porter apparently did not take part in the first mission flown by the First Day Bombardment Group on September 26, 1918, the opening day of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, when they were ordered out around 9 a.m. to bomb targets at Dun-sur-Meuse. Porter and observer Patten were, however, among the eight teams that set out a little after 3 p.m. to bomb the town and railway tracks at Etain, a few miles over the lines east of Verdun; they were apparently the only team that had to turn back before crossing the lines.61 American squadron records, unlike those kept by the R.A.F., do not provide reasons for early returns, but engine malfunction or another problem with the plane is likely—the DH-4s had their share of problems, and many of those allotted to the 11th Aero were, at least initially, in poor shape.62

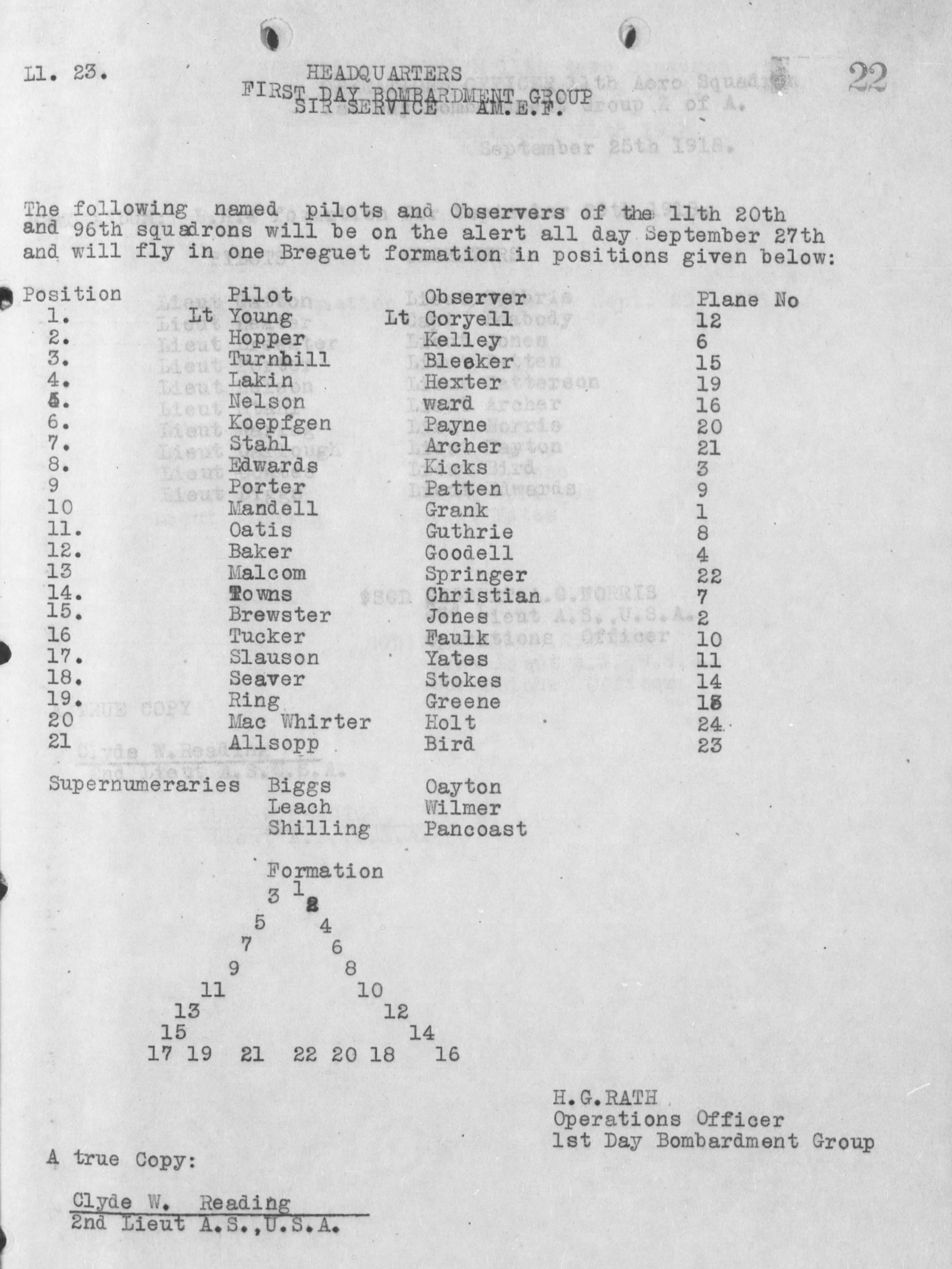

The next day, September 27, 1918, the First Day Bombardment Group squadrons, perhaps as much out of necessity as by design, flew in a single large formation for the first time. The 96th Aero had lost many pilots and observers, but was well supplied with Breguet 14 B.2 planes. For that day’s single mission, the 11th and the 20th each loaned at least seven teams to supplement the teams from the 96th.63 Pilots from the 11th included Porter (with Patten as his observer), Oatis, and Stahl; none of them had previously flown Breguets operationally. If Porter, like Oatis and Stahl, trained at Clermont-Ferrand, he would nevertheless have been familiar with the French plane. As far as I can tell, this was the only time Porter flew a Breguet on a mission.

The Breguet formation left Maulan late in the afternoon “for the purpose of bombing Mouzay, but on account of adverse weather conditions, changed its objective, and dropped 2 ½ tons of bombs on the town and railroad station at Etain.”64 Mouzay, beyond Dun-sur-Meuse, was about fifty-six miles due north of Maulan; Etain was slightly closer and farther east. Twelve teams, including three—available records do not specify which three— from the 11th, reached Etain; all planes returned safely.65 Enemy aircraft were sighted, and “A few shots were exchanged between our rear planes and enemy aircraft, which remained at a considerable distance.”66 James A. Summersett, the 96th’s historian, later wrote that “The success of the big formation, in spite of the prevalent idea that a six-plane formation was best, did more to raise the spirits and courage of the squadron than any incident in its history. When attacked, the planes could form a tighter fighting rear line than in a small formation, and often the sight of a well organized large formation was enough to warn enemy scouts of the hot reception to expect should they attack.”67

A similar combined mission to bomb Bantheville early the next morning (September 28, 1918) returned before crossing the lines when it was apparent that a storm was approaching from the east; I find no indication of which pilots flew on this aborted raid.68 On the 29th a late afternoon mission composed of a formation of (initially) nineteen Breguets flown by pilots of the 96th and the 11th,, followed by a formation of (initially) eighteen or twenty DH-4s piloted by men from the 11th, and 20th, bombed Grandpré and Marcq.69 Porter with observer Patten took part in this raid, but, like the majority of the teams, had to return early, as their planes could not keep up with the formation.70 No missions were flown on the last day of the month.

Stocktaking at the end of September 1918 showed impressive numbers of missions undertaken by the squadrons of the First Day Bombardment Group, but also a distressing number of casualties—thirty-eight men “missing,” distributed fairly evenly among the three operational squadrons.71

On October 1 and 2, 1918, Porter with observer Patten took part in missions that again consisted of two large formations, one composed of Breguets and one of DH-4s.72 On October 1, 1918, when the target was Bantheville, Porter’s DH-4 was one of the vast majority that had to return before reaching the lines. The next day the target was St. Juvin; according to Norris’s narrative account of the mission, all the planes of the 11th Aero, thus including Porter’s, reached the objective.73

Porter and Patten do not appear on lists of teams flying missions on October 3 and 4, 1918. The next day, however, they are listed as setting out with a large group of teams from the 11th and 20th and are among those noted as reaching the objective, which is given variously as St. Juvin, Doulcon, and Aincreville (just south of Doulcon).74

The 11th Aero flew at least eleven more missions during the remainder of October, and Porter and his observer Patten are documented as having taken part in eight of them; on two days (October 23 and October 30, 1918), they flew both in the morning and in the afternoon. The percentage of times they were able to reach and bomb the objective increased, perhaps as a result of more familiarity with and better maintenance of their plane.75

The days suitable for flying were slightly outnumbered by days of rain, and the 1922 squadron history gives Porter credit for this. The 11th and 12th of October were rainy,

which made it possible to secure a truck for the evening of October 12th and hie ourselves to St. Dizier [about fifteen miles west of Maulan] for a big celebration. Things started off quietly enough with a dinner at the principal hotel, in the course of which many of the brothers partook too freely of the flowing bowl and became rather boisterous. “Rain Dance” Porter gave a demonstration of his remarkable powers as a medicine man in the middle of the lobby of this same hotel. His wild incantations and prayers for rain proved good medicine for us all and were followed by five straight days of rain, clouds and wind, during which not a machine left the ground from our drome. Porter certainly proved his skill that night and was invariably called on whenever the weather looked as though it might clear enough for bombing operations.76

Porter took part in the mission of October 18, 1918, the first after the welcome week of rain. The mission is of interest in part because of its size: flights from the 11th, 20th, and 96th were joined for the first time by a flight of DH-4s from the 166th Aero. Also of interest is that, in a reversal of earlier roles, Spads from pursuit squadrons were evidently now detailed to provide protection for the DH-4s. Norris’s account of the raid notes that “Five enemy Fokkers D 7 approached the formation and were seen going down in flames with the Spads following”; the raid report notes two enemy aircraft seen going down in flames.77 Sixteen planes from the 11th took part in this mission; eleven, including Porter’s, reached and bombed Bayonville.78

Weather again precluded flying until October 23, 1918, when two missions were flown. Porter, with Patten, participated in both of them, and both times reached and bombed the objective. These raids were notable as being apparently the first ones that Porter flew that involved combat with enemy planes. The morning mission comprised a flight of twelve planes from the 20th Aero and a flight of thirteen from the 11th. The 20th took off at 8:35 a.m., with the 11th following ten minutes later; the 20th dropped their bombs on Buzancy at 9:50, and the 11th did the same five minutes later.79 Just minutes into the return flight, near Bayonville, “Six enemy planes were encountered” by the planes of the 11th Aero, “and a running fight ensued, but the enemy planes were successfully driven away.”80 In retrospect, the squadron attributed their success to tight formation flying: “We did not believe there were any Huns in the air who could break into the tight formation we were flying at that time without having at least two or three times our number. This confidence was in striking contrast to the earlier feelings we all experienced when formation flying, as practiced on later raids, was so little known.”81 The successful formation flying on this raid is all the more remarkable as five of the thirteen planes were not able to reach the objective, so that the remaining eight planes would have had to maneuver to close up gaps.

The afternoon raid involved all four squadrons. Porter, flying DH-4 No. 11 with Patten as his observer, was again one of thirteen pilots from the 11th on this mission, and apparently one of nine this time who reached the objectives, the Bois de Folie and Bois de Barricourt, just short and slightly east of the morning’s target.82 Once over the objectives, all four squadrons encountered enemy aircraft over a period of twenty-five minutes from 3:30 until 3:55, the 11th being the last to be attacked, by five enemy planes. The 96th, the 20th, and the 166th all experienced losses or forced landings, but the 11th came through unscathed.83

When the 11th flew its next mission, on October 27, 1918, there was again combat with enemy aircraft, but Porter’s DH-4 No. 11 is listed among the planes that had to return early. He and Patten were among the teams from the 11th that reached and bombed Damvillers the afternoon of October 29, 1918, and Nouart and Belleville on two missions on October 30, 1918.

After a three-day break, the First Day Bombardment Group flew two missions on November 3, 1918. In the morning the four squadrons set out shortly after 8:00; Porter, with Patten as his observer, was one of the thirteen pilots from the 11th Aero on this raid. Stenay, the primary objective, was obscured by clouds, so planes from the 11th instead bombed warehouses at Martincourt, just north of Stenay; Porter’s DH-4 No. 11 was one of the nine that reached the objective. Enemy planes were sighted, but kept their distance.

During the day’s second mission, however, when Porter, again flying DH-4 No. 11, was paired with observer Philip John Edwards, eight Fokkers attacked the planes of the 11th just as they had dropped their bombs on Beaumont at 3:10.84 “Our defensive fire was too hot for them to get within an effective range, although they persisted until two of their machines were seen to fall out of control.”85 Seven teams, including Porter and Edwards, were jointly awarded credit for the downed Fokkers.86

The 11th Aero flew two final missions, one on November 4, 1918, and one the next day, when they did not actually cross the lines (and Porter did not fly). Porter in DH-4 No. 11, once again with observer Patten, took part in the mission on the 4th. This was an afternoon raid on Montmédy; approximately forty-eight planes from the four squadrons participated. They were aggressively attacked by a large number of enemy aircraft over the course of twenty-five minutes as they approached the target and as, having dropped their bombs around 3:30, they turned towards home.87 During the encounter members of the 11th Aero sighted one enemy plane going down in flames, one crashing to the ground, and one going down out of control.88 Porter and Patten, jointly with John Eliot Osmun and his observer Edwards, were “credited with the destruction, in combat, of an enemy Albatros, in the region south of Stenay, at 10500 feet altitude, . . . at 15:30 o’clock”89 For the first time since September 18, 1918, however, the 11th suffered losses: pilot Dana Edmund Coates and his observer Loren Renfrew Thrall, and pilot Cyrus John Gatton and his observer George E. Bures were all killed in action that day.

The 1922 history of the 11th Aero credits Porter, as well as Gatton, Heater, and Oatis, with having flown thirteen raids with the 11th Aero; only one pilot, John Lawrence Garlough, is credited with more.90 By my count, Porter flew at least twenty-one missions with the 11th, but the history perhaps only includes ones during which the objective was reached.

At some point after the 11th’s final mission, and probably after the armistice, Porter was evidently involved in his first crash. A newspaper article dated December 30, 1918, reports that “A cablegram received by his father, Finley R. Porter, from Lt. Robert B. Porter . . . tells of his narrow escape from death recently when his plane crashed to the ground in the fog. Lt. Porter is now at a rest camp in France suffering from nerve shock, and has been pronounced unfit for further duty.”91 I find no other record of this crash, but Porter’s stay, from November 23 until December 19, 1918, at the Château de Cirey—which the owner had put at the disposal of the American Air Service to use as a convalescent home for aviators—is documented; he would while there presumably have encountered second Oxford detachment member and 166th Aero Squadron pilot Paul Vincent Carpenter, who had been ordered to the Château in early November 1918.92

Porter was able to return to the U.S. early in the new year on the Duca Degli Abruzzi, which arrived in New York on February 11, 1919.93 At the end of May, Eileen Newbold Tinkler of Stamford arrived in the U.S., fittingly, on the Carmania (which had originally taken Porter to England), and she and Porter were married in June.94 He worked as an engineer for the naval architecture firm Gibbs & Cox before retiring to Florida.95

mrsmcq July 25, 2022

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Porter’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Robert Brewster Porter. For his place and date of death, see “Robert Brewster Porter ’15.” The photo is a detail from a photo of his ground school class.

2 On the Porter family, see History of Washington County, Ohio, pp. 590–91, and Hubbard, General Rufus Putnam, p. 179.

3 Information taken from records available at Ancestry.com.

4 Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Robert B Porter.

5 Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Finley R Porter.

6 “Robert Brewster Porter ’15.” Richard Babcock Porter was also a member of the Princeton class of 1915, and he is presumably the “R. B. Porter” who appears in Princeton yearbooks after 1912.

7 “Porter to Build Cars at Port Jefferson, L.I.”; Ancestry.com, New York, State Census, 1915, record for Robert B Porter.

8 University of Pennsylvania, General Alumni Catalogue of the University of Pennsylvania, 1917, p. 394.

9 Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Robert Brewster Porter.

10 “American Airmen May Sail in July.”

11 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].” Note: I have not been able to identify one of the men listed with this class, H. A. Lorfok; his name also appears as H. A. Lorkol (“Graduates of the Aviation ‘Ground Schools’ Sept.1.”)

12 Foss, diary entries for October 7 and 21, 1917.

13 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917

14 See Foss, diary entry for November 15, 1917.

15 Ludwg, diary entry for November 29, 1917; and Chalaire, “Thanksgiving Day with the Aviators Abroad.”

16 Foss, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” (in Foss, Papers).

17 On No. 38’s planes and locations, see p. 403 of Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force.

18 Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925, pp. 38, 43, and 44.

19 Cablegrams 834-S and 1303-R. .

20 Fleet, Letter to Benson dated May 31 [1918], in Benson, Leslie A. A. Benson Collection, 1917-1919.

21 Wiser, Recollections of the DH-4, pp. 125–26.

22 See Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File, p. 307.

23 See Coulter, “Special Orders No. 105”; [Biddle?], “Special Orders No. 109”; and Dwyer, “Memorandum No. 8 for Flying Officers,” p. 4.

24 “11th Squadron,” p. 4. It is worth noting that Shoemaker indicated September 12, 1918, as the date of his arrival at the 11th when he was interrogated as a P.O.W.; see Kraft, [Documents], p. [33]. And see also Oatis’s postscript to his letter of September 12, 1918: “I’ve been assigned to my squadron.”

25 Thomas, The First Team, p. 56 (I have not been able to review his source, S.O. No. 184); see also p. 80.

26 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 147. See also the account of the numbers of pilots and observers available on September 10, 1918, on p. 92 of Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” which would support the September 9, 1918, date.

27 Tyler, Selections from the Letters and Diary, p. 125.

28 “First Day Bombardment Group,” p. 4.

29 Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3, p. 120 (editorial comment). Note: many of the documents in this volume were included in Gorrell, but I have not always chased them down to that source.

30 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 147.

31 This odd tasking may have been part of what prompted the 11th Aero and/or the First Day Bombardment Group to call themselves, according to Paul Stevens Greene, the “Bewilderment Group” (Ticknor, New England Aviators, vol. 1, p. 101).

32 Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3, pp. 87–8; see also orders reproduced ibid., pp. 148, 268, and 274. The names of the pilots can be determined based on various records; they did not include Porter.

33 Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3, pp. 147 and 148; p. 274.

34 Ibid., pp. 147 and 274.

35 Ibid.

36 Toulmin, Air Service American Expeditionary Force 1918, p. 363.

37 Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3, p. 147.

38 Thomas, The First Team, p. 68.

39 See the reports of these missions on pp. 69–74 of History of Second Pursuit Group. It is not clear that this represents a complete listing of the missions in which the 11th and 20th participated on these two days. Tyler’s diary entry for September 12, 1918, indicates that he went on patrol with the 139th that day (Selections from the Letters and Diary, p. 126), although no planes from the 11th are recorded as flying with the 139th in the missions listed on pp. 69–74 of History of Second Pursuit Group.

40 “22nd Aero Squadron,” p. 145. See also p. 144, where his observer is identified, almost certainly erroneously, as “Parront” [sic]—Edmund Anthony Parrott was an observer with the 20th Aero who had flown protection with Sidney Coe Howard earlier in the day.

41 History of Second Pursuit Group, pp. 69–74.

42 Tyler, Selections from the Letters and Diary of John Cowperthwaite Tyler, p. 126 (diary entry for September 13, 1918).

43 Brooks, “22nd Aero Squadron (Pursuit),” p. 9.

44 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 149.

45 Quotation from History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 149.

46 Tyler, Selections from the Letters and Diary of John Cowperthwaite Tyler, p. 127.

47 See Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 96. Under pressure of battle, record keeping clearly suffered, and the several accounts of operations, including this day’s are confused, confusing, and sometimes mutually contradictory. I have disentangled things as best I can.

48 Rath, “First Day Bombadment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 99; “11th Squadron,” p. 62.

49 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 54.

50 Rath, First to Bomb, pp. 102–03.

51 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 54.

52 Rath, First to Bomb, p. 103 (diary entry for September 17, 1918).

53 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 54; see also the raid report on p. 65 of “11th Squadron.” Note: Thomas, The First Team, p. 79, indicates that the 11th did not fly this day (and History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 153, is implicitly in agreement). Perhaps Norris was mistaken, or perhaps Thomas was unaware of the entry for this day in Norris’s History.

54 Rath, First to Bomb, p.104 (entry for September 18, 1918).

55 The relevant memorandum is reprinted on p. 232–34 of volume 2 of Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I.

56 Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 2, p. 239. And see Thomas, The First Team, p. 89.

57 Information on Cooper and Waring is scarce, but I find no record of their having been attached to an R.A.F. squadron or of work with an American squadron prior to their assignment to the 11th Aero.

58 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 264.

59 Maurer, ed. The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p. 372.

60 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 159.

61 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 106–110. Note: the original pages appear here out of proper order.

62 See Thomas, The First Team, p. 55; and History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 145.

63 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 161.

64 United States, Department of the Army, Historical Division, United States Army in the World War, 1917-1919, vol. 9, p. 144. Both Norris’s narrative account ([History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive]), p. 55, and the 11th Aero’s raid report (“11th Squadron,” p. 69), indicate that Dun-sur-Meuse was the objective; neither notes that their pilots were flying Breguets.

65 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 110; “11th Squadron,” p. 69; “History of the 20th Aero Squadron, 1st Army,” p. 220. There are some discrepancies in the accounts of numbers of teams. Rath’s list includes Allsopp; Allsopp’s Carnet (log book) has no entry for this date.

66 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 110.

67 Summersett, “96th Aero Squadron (Bombardment),” p. 21.

68 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 111.

69 Ibid., pp. 111–12; cf. “11th Squadron,” p. 71.

70 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 111–12.

71 Ibid., pp. 113–14.

72 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 115–17.

73 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 55.

74 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 121, lists Porter and Patten among the successful teams and indicates Doulcon as the objective. Rath’s diary (Rath, First To Bomb) for this date indicates St. Juvin and Aincreville (the latter just south of Doulcon) as targets; History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 163, names Aincreville. Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 55, and the relevant raid report (“11th Squadron,” p. 76) also name St. Juvin. To add to the confusion, Thomas, The First Team, p. 98, gives Doulcon as the target, but in describing this mission, relies in part on the description of the next day’s raid from “p. 163” [sic; sc. p. 165] of History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A. Finally, Coates’s log book names Landres [-et-St.-George], while also giving a starting time out of keeping with the other sources.

75 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” passim.

76 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 165.

77 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 56; “11th Squadron,” p. 80.

78 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” 129–30.

79 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 131; “11th Squadron,” p. 81 (raid report); “History of the 20th Aero Squadron, 1st Army,” p. 232 (raid report).

80 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 56.

81 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 169.

82 On p. 132 of Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” the list of planes that dropped out does not include Allsopp, although Allsopp’s carnet (log book) indicates that he “turned back at lines”; the list includes Stahl, which seems unlikely, given that he was credited with a victory on this raid.

83 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 133. See also History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 169.

84 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 146–47.

85 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 173.

86 “Confirmed Victories 11th Aero Squadron,” p. 6; see also Milling, General Orders No. 27, paragraph 20.

87 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations, p. 149.

88 “11th Squadron,” p. 89 (raid report).

89 Milling, General Orders No. 27, paragraph 26; see also “Confirmed Victories 11th Aero Squadron,” p. 6.

90 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 185.

91 “Lt. Porter’s Narrow Escape.”

92 “Rest Chateau,” pp. 87 & 86.

93 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Robert B. Porter.

94 Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, record for Eileen Newbold Tinkler; “Porter–Tinkler.”

95 “Robert Brewster Porter ’15.”