(Cedar Rapids, Iowa, July 1, 1893 – Los Angeles, May 14, 1961).1

Oxford, Grantham, Scampton ✯ Boscombe Down? ✯ Issoudun, Tours, 50th Aero ✯ The Meuse-Argonne Offensive ✯ After the armistice

McCook’s grandparents were born in Ireland. They emigrated to eastern Iowa, where his parents were born. His father, Peter Thomas McCook, not long after his marriage to Elizabeth Quigley in 1892, opened a clothing store in Cedar Rapids in partnership with three other men whom he gradually bought out; he became a prosperous and prominent businessman in the city.2 Thomas Forrest McCook was the couple’s first child; a daughter, Mary Catherine, was born in 1896. Another child, a son, Edward, was born in 1907, but died in 1913.3

McCook attended St. Mary’s College, a small liberal arts school founded by Jesuits in St. Mary’s, Kansas. He received “the gold medal for the highest honors of the senior class” when he graduated in 1915.4 An account of a traffic ticket, which he disputed, from 1916, suggests love of speed and a certain cockiness, traits not infrequent in stories of early pilots.5 When he registered for the draft in June 1917 McCook indicated he was working as an advertising manager in his father’s clothing store, but he had by this time already applied for the aviation service.6 Before the month was out, he was at Fort Omaha in Nebraska learning about balloons: “Yours truly had the pleasure of two flights in the captive balloon, attaining a height close to three thousand feet.”7 By early July he had been (re)assigned to ground school at the University of Illinois in Champaign.8 McCook’s accounts of both Omaha and Illinois in letters home are upbeat; of the latter he wrote that “There are about 197 of us here at Illinois. They are the finest bunch of young men, mentally, morally and physically I have ever been thrown in contact with. . . . The townspeople have gone out of their way in extending to us the good graces of Champaign.”9 McCook expected that he would begin actual flight training in the U.S.: “I will start flying soon if everything goes right at Rantoul, the big government aviation field situation [sic] fourteen miles north of here.”10 Flight training did begin at Chanute Field just south of Rantoul in July of 1917, but McCook learned that in the military what was expected was often not what happened.11 He was among twelve men in his ground school class of twenty-nine who, having graduated August 25, 1917, chose or were chosen for further training in Italy, not Illinois.

The 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” sailed from New York on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania, “one of the biggest liners afloat,” as McCook accurately described her.12 After a brief stop in Halifax, the Carmania, on September 21, 1917, set out to cross the Atlantic as part of a convoy. The voyage was uneventful, but excitement mixed with anxiety marked the last days, once the Carmania entered the danger zone where German submarines were known to be. September 28, 1917, was particularly nervous-making, for it was not until the next day that a destroyer escort arrived to protect the convoy. The Carmania and submarine danger were topics in a letter McCook wrote home. He noted, as other diarists aboard did, the “fine moon all the time we were in the war zone” and goes on to remark that “We all expected—at least I did—to take a sudden dip in the water before morning.”13 Parr Hooper similarly wrote that “Before the convoy [destroyer escort] met us I was all prepared for going down.”14 The War Birds diarist remarks, with the casual unkindness of youth, “Poor McCook, the ugliest man alive, is worried to death about subs. The boys, [Marvin Kent] Curtis and [Uel Thomas] McCurry, have kidded him until he sleeps in his clothes including his puttees and shoes.” In fact, there was a general order to the men to sleep clothed; photos do not bear out John McGavock Grider’s description of McCook, and the latter’s actual war record does not substantiate the implied cowardice.15

Oxford, Grantham, Scampton

The Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. There the men learned, to their initial considerable dismay, that they were not to go to Italy after all, but to train with the Royal Flying Corps in England. They attended ground school (again) at the R.F.C.’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford.

In early November 1917, twenty of the men went from Oxford to Stamford to begin flight training, but the vast majority, McCook included, were dispatched to Harrowby Camp, a machine gun school, near Grantham in Lincolnshire; they were in a holding pattern until places became available at R.F.C. squadrons. Fifty men were placed in mid-November, but the rest, McCook again included, remained at Grantham. They had spent two weeks learning about and practicing on the Vickers machine gun, and now moved on to the Lewis. Some of the tedium was relieved by planning for and enjoying an American Thanksgiving at Grantham, complete with an (American) football game prior to the feast. McCook wrote: “I need not tell you that it was a glorious exhibition. Forward passes, line plunges and flying tackles were there in abundance, and to say that the English were enthusiastic is putting it mildly. . . . There were a few bunged-up faces at the banquet that night, but the sight of forty turkeys baked only as turkeys can be baked, performed miracles that neither ointment nor court plaster could achieve.”16

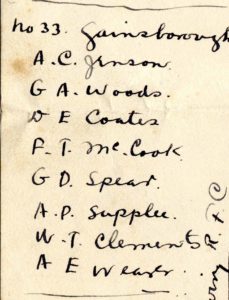

The next day, the members of the second Oxford detachment still at Grantham learned that on Monday (December 3, 1917) they would, finally, proceed to squadrons.17 McCook was one of eight men posted to No. 33 Home Defense Squadron at Gainsborough, about thirty-five miles north of Grantham.18 However, as, William Thomas Clements, also assigned to Gainsborough, wrote in his diary, “they didn’t know what to do with us after we got up there . . . We were sent out here to Scampton,” about ten miles southeast of Gainsborough, where a flight from No. 33 was located.19 (It was presumably at Gainsborough on this day that McCook wrote his letter about Thanksgiving, which opens “During a change in aero squadrons, I have a two hour stop over in this picturesque little north England town.”20)

Clements enthusiastically describes being taken up in an airplane for the first time the day after he and the other seven men arrived at Scampton and notes that “All of the boys had a ride, and some had two. The pushers are not dual control so all we are getting out of it is riding.”21 Clements, McCook, and the other men were evidently being taken up as passengers in the F.E.2b’s or the F.E.2d’s used by No. 33.22 These pushers (i.e., planes with the propeller behind the engine) were used by home defense squadrons for night fighting and were not designed as training planes. For the best part of two months the men made occasional flights as passengers but were otherwise at loose ends.23 Murton Llewellyn Campbell, posted to No. 81 Squadron, also at Scampton, wrote in his diary on December 29, 1917: “Ran across several of the fellows in the Home Defense Sq. . . . They have had nothing but joy riding with no instruction. Rather unfortunate, except that they have nothing to do but sit around and read.” It was surely frustrating for McCook to watch men like Murton Campbell at the same airfield flying Avros and Pups simply because they had been assigned to a different squadron. Finally, on January 26, 1918, the eight men at Scampton were reposted. It is clear from Clements’s diary entries for January 26 and 27, 1918, that he, Arthur Paul Supplee, and two others (unnamed) went to Waddington; “the other four” (also unnamed) “are going down near London some place.” It is probable that McCook was in the latter group.

Boscombe Down?

By late February 1918 McCook was training near Amesbury on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire. Excerpts from a letter written by him (no date provided) were reproduced in the Cedar Rapids Gazette of March 9, 1918, and the text makes clear he was training at one of the airfields near Amesbury, probably at No. 6 Training Depot Station at Boscombe Down.24

McCook’s description of Salisbury Plain contrasts markedly with his accounts of training (during the summer) in the U.S.:

They call it a plain . . . but this can only be a bit of English humor. . . . He who first used that phrase ‘bleak and desolate’ certainly referred to this place, as it is most adequate. . . . We are billeted in an abbey. . . . About two miles to the north there stands a pile of huge rocks, the ‘Stonehenge.’ Some enterprising land owner has inclosed the whole within a wire fence, and the admission to go in is two bob. . . . It was here the ‘Druids of old’ held their bloody sacrifices. Perhaps they too were ‘fed up,’ and mixed up with the gore to relieve the tension. One cannot blame them much. I am only telling you this that you may know how welcome France will look. The flying field itself, two miles in the opposite direction, has been most judiciously placed on the knob of one of the largest hills hereabouts. You can ‘take off’ down [illegible] hill no matter how hard the wind blows, but the landing is a proposition of quite different color. The camp is quite new.25

Like William Ludwig Deetjen, a second Oxford detachment member who trained at the Stonehenge airfield, McCook notes the presence of a prisoner-of-war camp for Germans at nearby Larkhill, and like Deetjen, grouses that the P.o.W.’s seemed to be better treated than R.F.C. cadets and officers.26 “Still we are getting good flying so I guess it is not for us to complain.”27 Assuming McCook was, indeed, at No. 6 T.D.S., he may have begun his training on DH.6s (a two-seater plane designed for training purposes) or on Avros or B.E.2c’s or B.E.2e’s (once operational two-seater aircraft now obsolete and used for training). He could have moved on to D.H.4s and D.H.9s, as well as B.E.12s, FK.8s and perhaps R.E.8s; the goal was to produce observation and bomber rather than scout pilots. Given his later squadron assignment, it is likely that McCook learned to fly DH.4s as part of his training.28

By sometime in March 1918 McCook had progressed sufficiently to be recommended for his commission as a first lieutenant. Pershing forwarded that recommendation, along with those for Charles Louis Heater and Robert Jenkins Griffith, who were both training at Boscombe Down, in a cable to Washington dated March 20, 1918. The cable confirming the appointments is dated April 2, 1918.29 McCook was placed on active duty on May 2, 1918.30

I have found no record of McCook’s further training, but he probably went from Wiltshire to an advanced flying school, perhaps Turnberry, where both Heater and Kenneth MacLean Cunningham (who also trained at Boscombe Down) were assigned for advanced training.

Issoudun, Tours, 50th Aero

In early July McCook, along with a number of other British-trained American pilots, including quite a few from the second Oxford detachment, was ordered to the American 3rd Aviation Instructional Center at Issoudun in the Loire region of central France.31 On July 14, 1918, he was one of ten men (including second Oxford detachment members Temple Paul Hardin and William Hamlin Neely) who were directed to proceed to the 2nd Aviation Instruction Center at Tours, about seventy-five miles to the northwest of Issoudun.32 Another of the men going from Issoudun to Tours was Harold Ernest Goettler who, in his diary entry for July 19, 1918, noted that “Hardin, [Winfield Earl] Sisson, Neely and McCook received a little dual on the old French Breguets that are in camp.” McCook apparently became proficient enough on Breguets to serve briefly as an instructor. An entry from around this time in the log book of second Oxford detachment member Robert Thomas Palmer indicates that he, Palmer, flew twice in a Breguet as McCook’s passenger before going solo. On July 26, 1918, Goettler recorded “my first flip in a Liberty four and am crazy over the machine,” and the other men probably also had the opportunity to try out the American version of the British DH.4.33

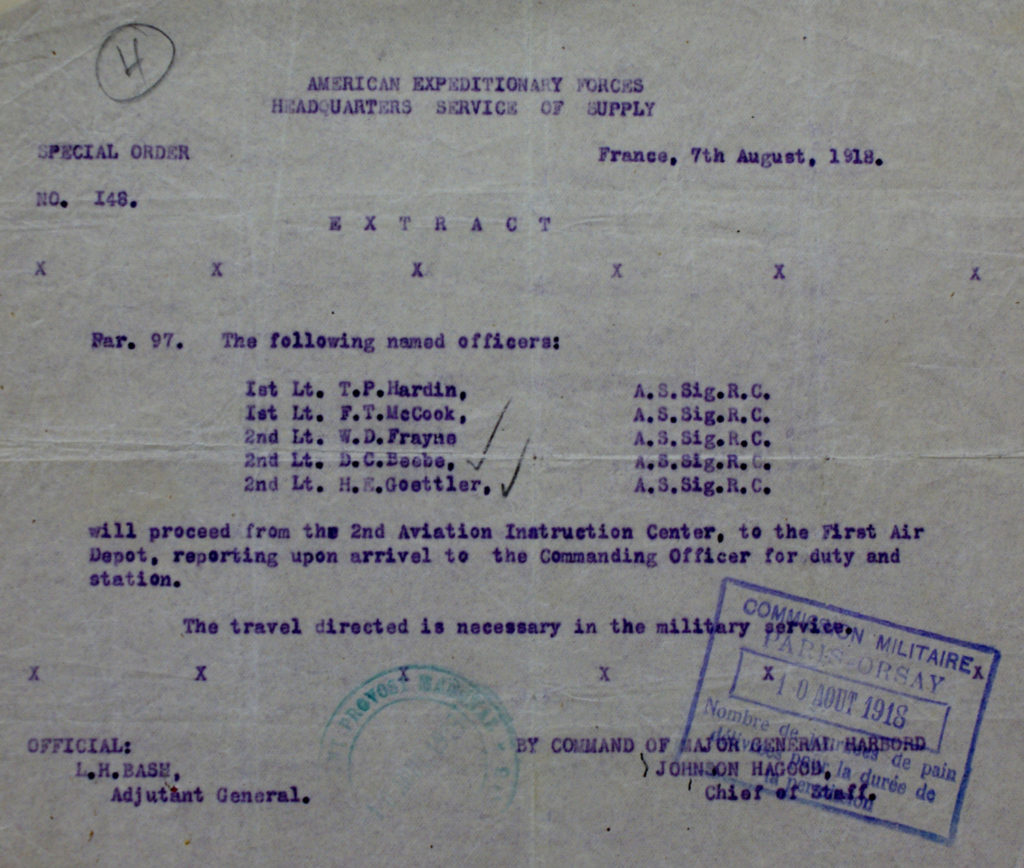

On August 7, 1918, McCook, as well as Hardin, Goettler, William David Frayne, and David Chapin Beebe were ordered to proceed from 2 A.I.C. to the 1st Air Depot at Colombey-les-Belles, some 250 miles to the northeast in Lorraine, where the American 1st Army’s sector of the front was located.34

Once arrived, the men were assigned to the U.S. 50th Aero Squadron, an observation squadron which was at this time stationed at Amanty about thirteen miles to the west of Colombey-les-Belles. The earliest firm documentation of McCook at Amanty that I have found comes from Goettler’s diary entry for August 16, 1918: “McCook and I practiced a little revolver shooting during the afternoon and now I am willing to take him on for a dual.”35 Some of the men assigned as pilots to the 50th Aero had had little or no experience with the squadron’s operational aircraft, the American “Liberty” DH-4, and those who had been trained on DH.4s in Great Britain helped the men new to the machine become accustomed to the American version of the plane. The experienced men certainly included Goettler, Beebe, Frayne, and Allen Tracy Bird and presumably also McCook and Hardin.36 When the squadron was divided into three flights later in August, Goettler, McCook, and Hardin were designated flight commanders of flights 1, 2, and 3, respectively.37

During the course of August, the pilots of the 50th Aero ferried DH-4s from the 1st Air Depot to Amanty; they tested the planes and associated equipment, making needed adjustments, and practiced and trained. They took advantage of this period of calm to play baseball with men of the U.S. 8th Aero Squadron, also at Amanty, and to socialize with men of the U.S. 135th Aero, stationed at Ourches-sur-Meuse just ten miles to the north. Second Oxford detachment members Edward Carter Braxton Landon and Wilbur Carleton Suiter were among the pilots of the 135th who motored down to Amanty towards the end of August to invite men from the 50th to Ourches “for their squadron dance.” Goettler, Daniel Parmelee Morse (C.O. of the 50th Aero), McCook, and others drove up there August 29, 1918, for a well-lubricated supper to which “a bunch of nurses” had also been invited; the dancing afterwards was lively.38

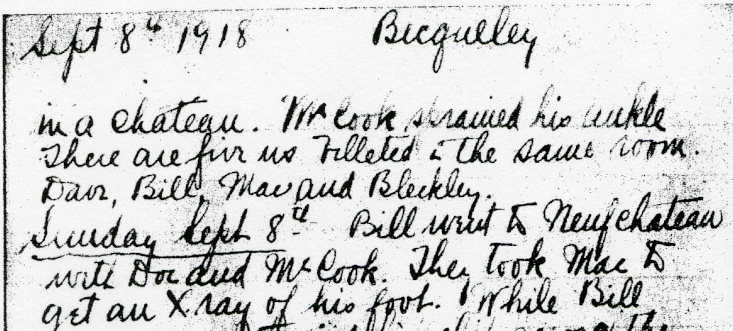

The squadron moved twice in the early days of September in the run-up to the St. Mihiel Offensive. They were initially ordered from Amanty northwest to the aviation field at the former Ferme Ste. Catherine between Bar-le-duc and Behonne, where they were to work with the 5th Corps Observation Group of the American 1st Army.39 Five days later, on September 7, 1918, they were reassigned to the 1st Corps Observation Group and moved east to Bicqueley, just south of Toul: “McCook’s flight took off first.”40 Once arrived, “We had supper at the construction squadron and returned to the village and found our billet to be in a chateau. McCook sprained his ankle. There are five [of] us billeted in the same room. Dave [Beebe], Bill [Frayne], Mac, and [Erwin Russell] Bleckley.”41 McCook’s injury—cause not specified—was sufficiently serious that the next day “Bill went to Neufchateau with Doc [Laurent Gustav Feinier] and McCook. They took Mac to get an Xray of his foot.”42

And the injury was evidently also sufficiently serious that McCook did not fly during the St. Mihiel Offensive, which opened on September 12, 1918, with the 50th making its last flight in support of it on September 18, 1918.43

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive

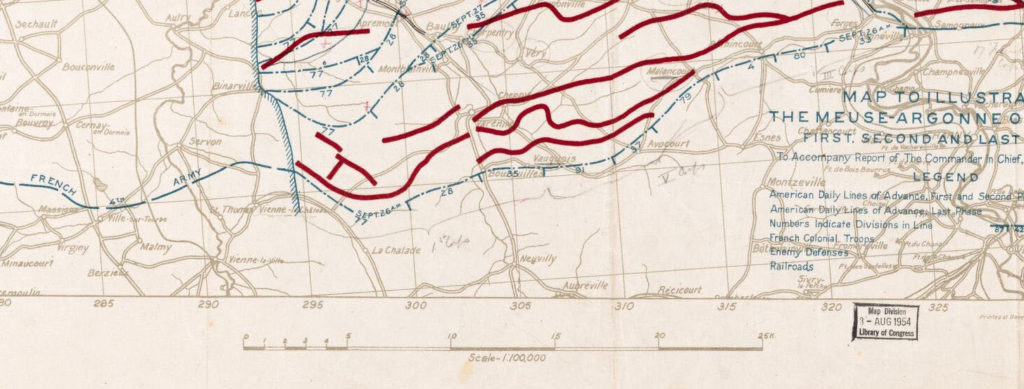

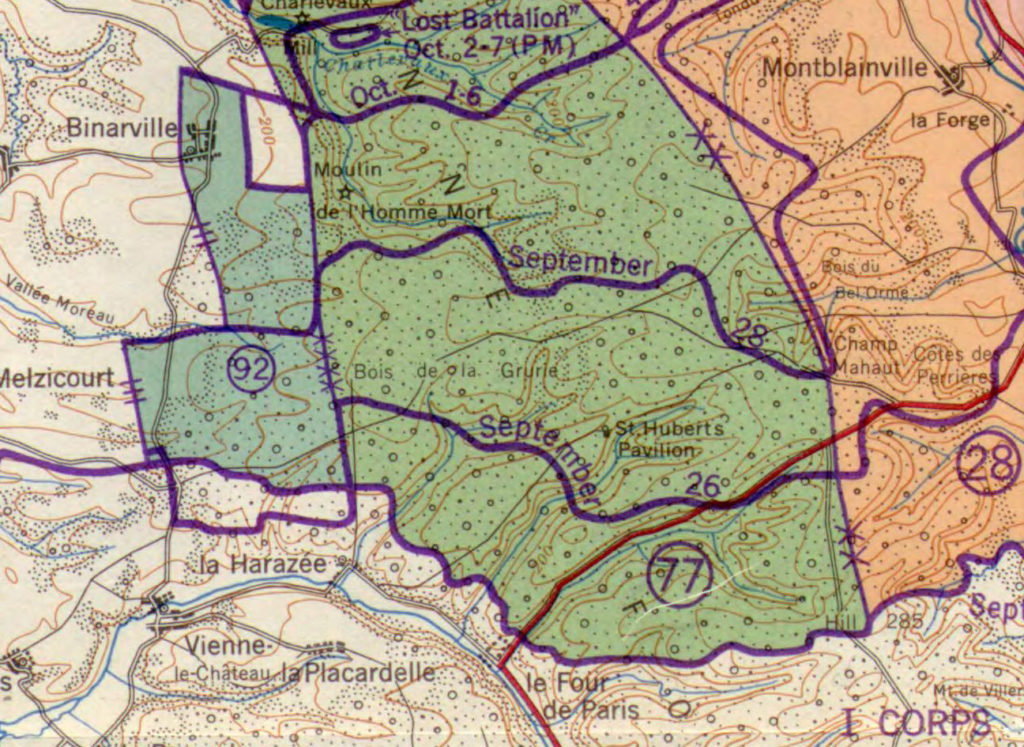

The men of the 50th Aero had but a few days respite in the aftermath of the successful St. Mihiel Offensive. On September 22, 1918, they learned they were to move again; orders had come for the 1st Corps Observation Group to relocate to Remicourt, to the west of their earlier station at Bar-le-Duc, in order to be in position when the Meuse–Argonne Offensive opened on September 26, 1918. The squadron’s trucks began arriving at Remicourt the next day, but bad weather meant that the planes could not fly until September 24, 1918. According to Goettler, “Mac & part of his flight got lost and landed at Epiez near Amanty.”44 Others also had difficulties, but by the end of the day the three flights were at Remicourt. All had been cautioned not to approach the lines, as it was necessary to prevent “the German intelligence from learning the numbers or disposition of Liberty planes.”45 “After supper we were told that we would work with the 77th Division and our sector was part of the famous Argonne Forest.”46 The 77th Division was at the westernmost edge of the American 1st Army’s front, which straddled the Argonne Forest with a planned line of attack stretching approximately twenty-five miles east to the Meuse River. To the left (west) of the American 1st Army, the French Fourth Army, with its 38th Corps as its rightmost element, was positioned to attack along a line extending a similar distance west from the Argonne to the Suippes River.

On the opening day of the Meuse–Argonne Offensive, September 26, 1918, once morning mist had dissipated, the weather was favorable, and the 50th Aero was able to make “18 sorties.”47 Several of these, including the one flown by McCook with observer James Emerson Sain, were infantry contact patrols.47a The primary purpose of such patrols was to locate the front lines of infantry and to report the location back to division headquarters—other means of communication becoming less reliable or nonexistent as troops advanced. Infantry were supposed to communicate their position to planes by means of flares or large white rectangular panels. Inadequate training and having other tasks to hand under combat conditions meant that infantry often failed to respond to requests to show their position. When this happened, pilots had to fly at low altitudes, well within range of enemy rifles and machine guns, to allow their observers to locate the front lines by direct observation. (In a post-war “lessons learned” report, McCook wrote that “Should the advance be great . . . [f]lares or panels . . . can not be expected as the infantry will generally throw them away to lighten their load.”48)

On the second day of the offensive, September 27, 1918, McCook, with William A. Bolt as his observer, flew one of the four missions undertaken by the 50th Aero (bad weather precluding greater activity).49 McCook and Bolt’s mission was reconnaissance, flying over the enemy lines and reporting back on enemy activity. That evening observer Milton Keith Lockwood wrote in his diary that “I have been assigned McCook as my regular pilot and number seven ship.”50

On September 28, 1918, starting at 6:15 a.m., the 50th sent out four infantry contact patrols for the 77th Division, with the last plane returning at 5:30 p.m.; infantry were proving better able to indicate their position.51 Although pilots from the 50th Aero were not directed in operations orders to cooperate with the French 38th Corps Squadron until orders issued on September 29, 1918, for September 30,52 there was evidently a request issued the afternoon of the 28th for an additional infantry contact patrol to locate the French line.53 Thus McCook and Lockwood left the airfield at Remicourt in DH-4 32175 (“number seven ship”) just before 4:00 p.m. that Saturday. In his diary and in a letter home Lockwood provided accounts, which differ in some details, of what happened that day. “We were out to find the lines for the French, after checking out at Division Hdqrs, where we received the panel ‘where are the advance elements?’ which meant to find their line as well. We passed over one of our batteries, . . . then flew over to Vienne-le-Château,” (a little over a mile west of the dividing line between the French and the American sectors).54 “Three planes ran us out so we got down to about 100 ft. and scooted over the line, zigzagging and circling as fast as we could, trying to pick up the men. Knew when we were over the Boche by the heavy rifle and machine gun fire from the ground.” “On the circle back I fired up my rocket and when it went off we were directly over the boche machine gun nest. The stars floated down signaling our infantry to show by flare where they were, in that way we could have put a barrage on the boche and driven him out, and knowing our own line would not have shot that up. But I never saw any flares, for the boche turned loose at us at about 100 feet.”55

German bullets struck the plane: “A spark plug blew out of the engine—evidently the result of a bullet and both gas tanks were shot full of lead. The sparks were pouring out of the engine and there were three inches of gasoline at the bottom of the fuselage. . . .” McCook landed the plane in barbed wire in no man’s land, and he and Lockwood ran south amid machine gun fire towards the French lines. With the assistance of French soldiers they made it to a front line trench. “Hunted up one of their officers and got their position from them and got a guide to take us back to their P[ost of] C[ommand]. Told them to station a machine gun to command the plane and not let the Boche get to it, as it was impossible for the French to get it themselves.” (The machine gun evidently did its job. Although apparently not used again operationally, DH-4 32175 was apparently salvaged in early November.56

The French guided McCook and Lockwood to American troops, men of the U.S. 92nd Division’s 368th Infantry Regiment, which was awkwardly sandwiched between the French front and the 77th Division.57 “We passed back thru trenches that were Boche that morning and they were wonderfully well fixed up.” As pilot and observer made their way south, they were still in range of German machine guns and had to take cover more than once before reaching Vienne-le-Château. At some point in their journey Lockwood found a phone and made his report as to the location of the line.58

The work of McCook and Lockwood was singled out when the next day’s operations orders for the 1st Corps Observation Group were written that evening: “Lieut. Lockwood (Observer) and Lieut. McCook (Pilot), 50th Aero Squadron, who left the field at 15 H:52 on an infantry contact patrol on the left of the 77th Division sector, were shot down and fell in No Man’s Land, but succeeded in escaping to the French Lines and transmitting shortly afterwards the valuable information they had obtained”; their actions were described as a model for all observation crews.59

Meanwhile, McCook and Lockwood ate with staff officers at Vienne-le-Château: “had a fairly good supper and slept in wet clothes and blankets in a dugout.” The next morning, they explored Vienne-le-Château, which, they discovered, was still within range of German gunfire, and eventually headed on foot and by truck to Florent-en-Argonne several miles south-southeast of Vienne-le-Château. Squadron C.O. Morse met them at Florent and, after further debriefing, they went “home again to wait around for a new plane.”

They did not have to wait long. Lookwood writes that “Two days after Mac and I came down in No Man’s Land, we went up on another infantry liaison over the same territory and while there the engine went bad and we had to come down. Headed south all right and got five kilometers back before we had to land but it was in barbed wire again and in such a place that the ship had to be abandoned and turned in for salvage.”60 This incident is not mentioned in the unusually detailed summary of operations of the 1st Corps Observation Group that day, and Lockwood, who had neglected his diary for nearly three weeks, was recalling events from some time ago.61 Thus the date of the incident is open to question.

Although accounts of McCook’s missions in the first weeks of October 1918 are lacking, it is clear that he flew frequently and participated in the effort to locate and assist the so-called “Lost Battalion” during the period from October 3 through October 7, 1918.62

Lockwood is again the source for the next specific information about McCook’s work:

Yesterday [October 18, 1918], we went up on [infantry contact work] and lost our protection immediately but continued up there. Never saw so many ships in the air at one time in my life. We would barely get up to the 77th Division Hdqrs. when we would get chased back. Had one formation of six get on us but we got away all right and ducked back in but it was continually virage out of the way and grab the guns until the other planes either turned off or showed their colors. Got the line all right but Mac had to work continually for other planes coming toward him, there were so many.63

By this date the 77th Division, which had reached Grand-Pré, had been relieved by the 78th.64 Lockwood’s reference to the 77th may be a slip of the pen, or perhaps there was still work being undertaken for the 77th. In any case, a letter dated the next day (October 19, 1918) at the “P.C. 78th” and signed by Donald Marion McRae, an A.E.F. staff officer, expressed appreciation for the work: “The message dropped by one of your planes at 4:15 P.M. 18th instant, giving our line east of Grand Pre, confirmed our information and was of material value. Definite information of this nature is of great value to me. We realize the difficulties you are up against and appreciate the work done for us by Lt. McCook, Lt. Lockwood, Lt. Beebe, Lt. Rogers, Lt. Bird and Lt. Brill.”65

At the end of his diary entry for October 18, 1918, after an account of the 50th’s losses (Goettler and Bleckley had perished during the effort to relieve the “Lost Battalion”) Lockwood notes with satisfaction the progress of the Meuse–Argonne Offensive: “The attack is going fine tho and the troops are way up past the Argonne and Grandpré. It takes nearly forty minutes to reach the lines now.” This increasing flying time was presumably behind the decision ten days later to move the 50th Aero about fifteen miles north-northeast to Clerment-en-Argonne.66 Two days prior to this move, McCook, getting a brief break from front-line flying, was among four men from the 50th who visited what was apparently the 78th Division headquarters at Chatel-Chéhéry.67

The 50th Aero continued flying daily infantry contact and reconnaissance patrols for the 78th Division (as well as, late in the war, for the 77th again) from their new airfield at Clerment.68 McCook participated in the squadron’s final mission of the war, a protected infantry contact patrol the afternoon of November 6, 1918. Two days previously, Lockwood and pilot Beebe had been shot down and, unhurt, taken prisoner. On November 6 McCook thus had a different observer: David Merton Hunt according to one source, Harry Warren Pribnow according to another.69 In an uneventful mission, McCook flew DH-4 # 23, one of two planes protecting pilot Frayne and his observer.70 Bad weather precluded further flying on the final days of the war.

50th Aero Squadron C.O. and historian Morse provides a listing of the “number of missions and total hours over lines of pilots and observers.”71 It shows McCook having flown twenty-three missions for a total of thirty-three hours, making him one of the most active of the squadron’s pilots, despite his not having flown during the St. Mihiel Offensive. According to a post-war newspaper article, McCook was singled out twice for commendation; the letter from McRae was cited above. On November 30, 1918, another citation was issued: “The air service commander, First army, cites the following officers and men for exceptional devotion to duty: First Lieut. F. T. McCook, pilot of the Fiftieth aero squadron, by energetic and courageous work as flight commander, aided in establishing the squadron’s record.”72

After the armistice

Shortly after the armistice, the squadron was detached from the 1st Observation Group and split into three flights. McCook was in charge of B flight, which, once weather permitted, left for the 3rd Corps School at Clamecy in Burgundy—where all three flights eventually joined up. McCook and other officers of the 50th at Clamecy “occupied their time giving lectures and joy rides, and working on field problems to improve infantry contract duties” as they waited to return to the U.S.73 McCook, along with fellow squadron member Hardin and Cunningham, who had flown with No. 55 Squadron R.A.F., sailed for home from Brest on March 28, 1919, on the S.S. America.74 Soon after arriving in Boston April 5, 1919, he learned of his promotion to captain.75

Back in Cedar Rapids, McCook continued to fly, initially as one of the partners in the “McCook-Doty Aeroplane Company.” He was also working at his father’s clothing store, which increasingly demanded his attention. In the 1930s he moved to California where for a time he served as a flying instructor.76

mrsmcq January 29, 2020

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 McCook’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Thomas Forrest McCook. (In many later records his first and middle name are given as “Forrest Thomas.”) His place and date of death are taken from “Forrest McCook.” The photo is from p. 35 of Dotson, Honor Roll of Linn County Iowa: An Illustrated Biography, Compiled from Private Authentic Records. I am grateful to the staff of Stewart Memorial Library at Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, for providing a copy.

2 On McCook’s descent and family see records available at Ancestry.com. On his father, see “He is Now a Sole Proprietor.”

3 “7-Year Old Son of P. T. M’Cook is Dead.”

4 “St. Marys Graduates Fourteen.”

5 “Mt. Vernon Motor Cop Chases Auto to Cedar Rapids.”

6 See the draft card cited above and “Young McCook a Local Boy.”

7 See “They Warn Against Waste in England” and “The Soldiers’ Letter Box”; the quotation is taken from the latter.

8 “Maurice Connolly to Take up War Flying.”

9 “The Soldiers’ Letter Box.”

10 Ibid.

11 On Chanute Field, see Hanson, Rantoul and Chanute Air Force Base, p. 9.

12 “Forrest M’Cook in Royal Flying Corps.”

13 Ibid.

14 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of September 21, 1917, continuation September 30, 1918.

15 I write “Grider’s” advisedly; this early part of War Birds includes substantial borrowings from his diary (see Vaughan, Letters from a War Bird, pp. 286–87). The mentions of Curtis and McCurry, who were at ground school with McCook and Grider also point to Grider’s authorship of the passage. It seems callous but not uncharacteristic of Elliott White Springs to have retained the passage and to have presented a copy of the book to McCook; see “M’Cook Gets Copy of ‘War Birds’.” On the order to sleep clothed, see Jesse Frank Campbell’s diary entry for September 28, 1917.

16 “Letter from M’Cook Some Globe-Trotter,” p. 2.

17 Clements, diary entry for November 30, 1917.

18 See Foss’s list of “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers.

19 Clements, diary entry for December 3, 1917.

20 The letter is reproduced in part in “Letter from M’Cook Some Globe-Trotter,” for which the newspaper supplied the date “December 2, 1917,” which should perhaps be “December 3, 1917,” as there is no indication that McCook preceded the other seven men to No. 33 Squadron.

21 Clements, diary entry for December 4, 1917.

22 On the planes available to the squadron, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 401.

23 Clements, diary, passim.

24 “Letter from M’Cook Some Globe-Trotter,” pp. 2 and 3.

25 Ibid. I have not been able to identify an abbey in or near Amesbury that was used to house R.F.C. men. It is possible that McCook was quartered at Amesbury Abbey, a country house near the former Amesbury Priory, but I have not been able to determine whether this residence was used to house R.F.C. men during this period.

26 See Deetjen, diary entry for May 15, 1918.

27 “Letter from M’Cook Some Globe-Trotter,” p. 3.

28 On the planes available at No. 6 T.D.S., see Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 294, as well as “Introduction and new Question TDStations” (post #5 by mickdavis); Sturtivant et al. do not list the R.E.8, while mickdavis does.

29 Cablegrams 756-S and 1028-R.

30 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

31 I am grateful to Steve Ruffin for copies of various relevant special orders. Both S.O. No. 109, issued by Major General [John] Biddle, and S.O. No. 105, issued by Brigadier General [Richard] Coulter, directed men, including McCook, to proceed to Issoudun. Some extracts of S.O. No. 109 appear to have been misdated.

32 Benedict, “Special Orders No. 192.”

33 Goettler, diary entry for July 26, 1918.

34 Harbord, “Special Order No. 148.”

35 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 326, indicates McCook joined the 50th on August 12, 1918.

36 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 316, indicates that Henry “Harry” LeNoble Stevens also provided instruction on DH-4s.

37 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 23; Goettler, diary entry for August 21, 1918.

38 Goettler, diary entries for August 28 and 29, 1918.

39 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 24, and Goettler, diary entries for September 3 and 4, 1918.

40 Goettler, diary entry for September 7, 1918.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid., entry for September 8, 1918.

43 See the operations reports for September 12–September 18, 1918, on pp. 81–84 of “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account.”

44 Goettler, diary entry for September 24, 1918.

45 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 33.

46 Goettler, diary entry for September 24, 1918.

47 See the list on p. 35 of Morse, The History of the 50th Aero squadron, and Hall and Echols, “Daily Operations Reports,” p. 171. I should note here that the main historical sources to which I have had access are not always in accord. Morse’s The History of the 50th Aero Squadron is a revised version of “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account,” which is included in Gorrell’s History of the American Expeditionary Forces Air Service, 1917 – 1919. In some instances the revisions involve accurate corrections–regarding, for example, the date of the squadron’s move to Behonne—but in some places, e.g., the accounts of the opening days of the Meuse–Argonne Offensive, the revisions are confusing, and they do not always correlate with information provided in Chief of Air Service 1st Army Corps Hall’s summaries of operations in his “Daily Operations Reports.” Unfortunately, none of the accounts provides a detailed record of missions flown by the pilots of the 50th Aero such as one would find in a squadron record book. The diaries of Goettler and Lockwood (see below) provide valuable, though limited, means of verifying the general accounts.

47a The schedule for September 26, 1918, drawn up by operations officer Stewart Bird for Morse, reproduced on p. 91 of “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account,” has McCook flying with Lockwood, while Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 35, pairs him with Sain. The entry for September 27, 1918, in Lockwood’s diary suggests that the latter is accurate; see Ruffin, “‘The Luckiest Man in the Army’,” pp. 172–73.

48 McCook’s report can be found on pp. 168–69 of “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account” and pp. 139–41 of Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 4.

49 See Ruffin, “‘The Luckiest Man in the Army’,” p. 173 for Lockwood’s diary entry for September 27, 1918 (“Bad weather today”) and Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 36. In contrast, “The Reduction of the Argonne Forest,” p. 11, and Hall and Echols, “Daily Operations Reports,” p. 172, indicate that “atmospheric conditions” were favorable and visibility fair after 10:00 a.m.

50 Quoted p. 173 of Ruffin, “‘The Luckiest Man in the Army’.”

51 On infantry contact patrols flown see the summary of that day’s operations on pp. 174–76 of Hall and Echols, “Daily Operations Reports.” Morse, p. 36 of The History of the 50th Aero Squadron notes improved infantry cooperation; his summary of operations at the top of that page differs from the account in the “Daily Operations Reports.”

52 “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account,” p. 118.

53 A newspaper account (“Lieut. Lockwood Leading Men on Familiar Fields”) apparently erroneously indicates that McCook and Lockwood had been charged with locating “the German front line.”

54 This and subsequent quotations are from Lockwood’s diary entry for September 30, 1918, reproduced on pp. 173–74 of Ruffin’s “‘The Luckiest Man in the Army’” unless otherwise noted.

55 From Lockwood’s account, presumably in a letter home, quoted in “Lieut. Lockwood Leading Men on Familiar Fields.”

56 Based on documents in the possession of Steven Ruffin.

57 On the 368th, see, i.a., American Battle Monuments Commission, 92d Division, Summary of Operations in the World War, pp. 6–25; Williams, “African Americans in the Meuse–Argonne Offensive”; and Laplander, Finding the Lost Battalion, passim.

58 The accounts in Lockwood’s diary and his letter home appear to differ with regard to when and where he made his report.

59 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 37.

60 This is from Lockwood’s retrospective diary entry of October 19, 1918, reproduced on p. 174 of Ruffin’s “‘The Luckiest Man in the Army’.”

61 See Hall’s summary of operations on p. 180 of Hall and Echols, “Daily Operations Report.”

62 See Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 53.

63 Lockwood, diary entry for October 19, 1918, quoted on p. 174 of Ruffin’s “‘The Luckiest Man in the Army’.”

64 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 65.

65 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 56.

66 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, pp. 58–59.

67 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 69.

68 Hall and Echols, “Daily Operations Reports,” passim.

69 See Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 63; Ruffin “‘Dutch Girl’ Over the Argonne,” p. 129. Ruffin (private communication) indicated that his source was a schedule of missions drawn up by operations office Stewart Bird on the orders of Morse. Morse may have misremembered the makeup of the crews when he wrote his history, or the crews may have been changed between the time the schedule was drawn up and when the missions were actually flown.

70 Ruffin, “‘Dutch Girl’ over the Argonne,” p. 129.

71 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 83.

72 “Capt. F. M. [sic] M’Cook Home with Stirring Stories of Service.”

73 Ruffin, “‘Dutch Girl’ over the Argonne,” p. 129.

74 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list S.S. America.

75 “Capt. F. M. [sic] M’Cook Home with Stirring Stories of Service.”

76 Langton, “The aviators: First regional air service delivered Gazette to subscribers”; Ancestry.com, 1940 United States Federal Census, record for Forest [sic] T. McCook.