(Dumont, New Jersey, August 8, 1894 – St. Petersburg, Florida, April 6, 1941).1

Flight training ✯ France and the 135th at Ourches ✯ St. Mihiel and after ✯ The 135th at Toul

Though born in New Jersey, Fleet came from an old Virginia family. His father, William Hamilton Fleet, appears to have been a direct descendant of Henry Fleete of Chatham, Kent, who sailed to Jamestown in 1621 on the George and was influential in the development of both Virginia and Maryland.2 In the aftermath of the Civil War, Fleet’s father left Virginia for New Jersey and New York where he established himself as a furrier.3

Fleet attended Polytechnic Preparatory School in Brooklyn and Culver Military Academy in Indiana; he did not go on to college.4 When he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, he was working as a manager at his father’s fur business in New York City. He attended ground school at Ohio State University; there are photos of him (“Rox”) there with his friends Parr Hooper and Guy Samuel King Wheeler. Their squadron graduated from ground school on August 25, 1917.5

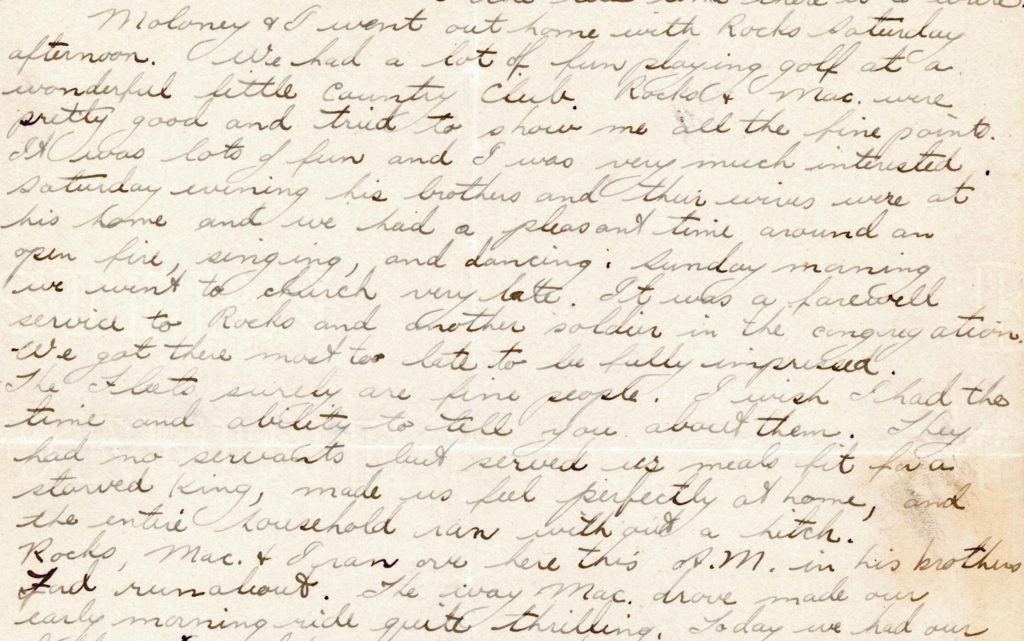

Fleet was one of the eighteen men from this class at O.S.U. who chose or were chosen for training in Italy. The men reported to the air field at Mineola on Long Island in early September, but were permitted to leave the field from time to time. One weekend, Fleet had his O.S.U. classmates Hooper and Clarence Bernard Maloney out for an enjoyable weekend at his home in Dumont, New Jersey.

A little over a week later, on September 18, 1917, they, along with the other members of the “Italian detachment,” boarded the Carmania and set out from New York for Halifax. On September 21, 1917, the Carmania left Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing. After an uneventful Atlantic crossing the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. There the men learned, to their dismay, that they were to go not to Italy, but to Oxford. They spent the month of October going through ground school (again) at Oxford’s School of Military Aeronautics. On November 3, 1917, most of the detachment, including Fleet, boarded a train bound for Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire where they were to attend machine gun school.

In mid-November about fifty of the men at Grantham were selected to go on to flying schools, and Fleet was initially in this group. However, he and his O.S.U. classmate Wheeler, about ten days into their stay at Oxford, had been reported for “flirting.”6 Their fellow second Oxford detachment member William Ludwig Deetjen noted that “we have been cautioned continually about the women at Oxford, London, and all England and France. To be with them means dishonorable discharge, 87% being diseased. This actually from our C.O.”7 Fleet and Wheeler were, according to another second Oxford detachment member, Fremont Cutler Foss, initially told “to pack up for France,” but then let off with a warning.8 Having thus, however, gotten on the wrong side of Colonel Bertram Richard White Beor, the unpopular commanding officer of the School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford, Fleet and Wheeler were removed from the November list of men going from Grantham to flying schools.9 Fleet was thus still at Grantham on November 29, 1917, when the second Oxford detachment members celebrated Thanksgiving. He appears in a photo of the “Unfits,” the winning team at that day’s football game (the opposing team was the “Hardly Ables”).10

Flight training

Soon after Thanksgiving word came that the remaining men at Grantham were to be posted, and on December 3, 1917, Fleet, along with Leslie Alfred Amzia Benson, Francis Joseph Hagan, Maloney, William Henley Mooney, and Wheeler, was assigned to No. 112 Squadron, a home defense squadron at Throwley in Kent.11 From there he apparently went to Stamford. There are photos taken by him of second Oxford detachment member Clark Brockway Nichol’s fatal accident at Stamford on February 18, 1918, as well as a photo captioned “Davis, my instructor at Stamford,” taken in April 1918.12 By early April Fleet had had sufficient experience flying to be recommended for his commission, and Pershing forwarded the recommendation in a cable dated April 8, 1918. It took over a month for the confirming cable to arrive.13

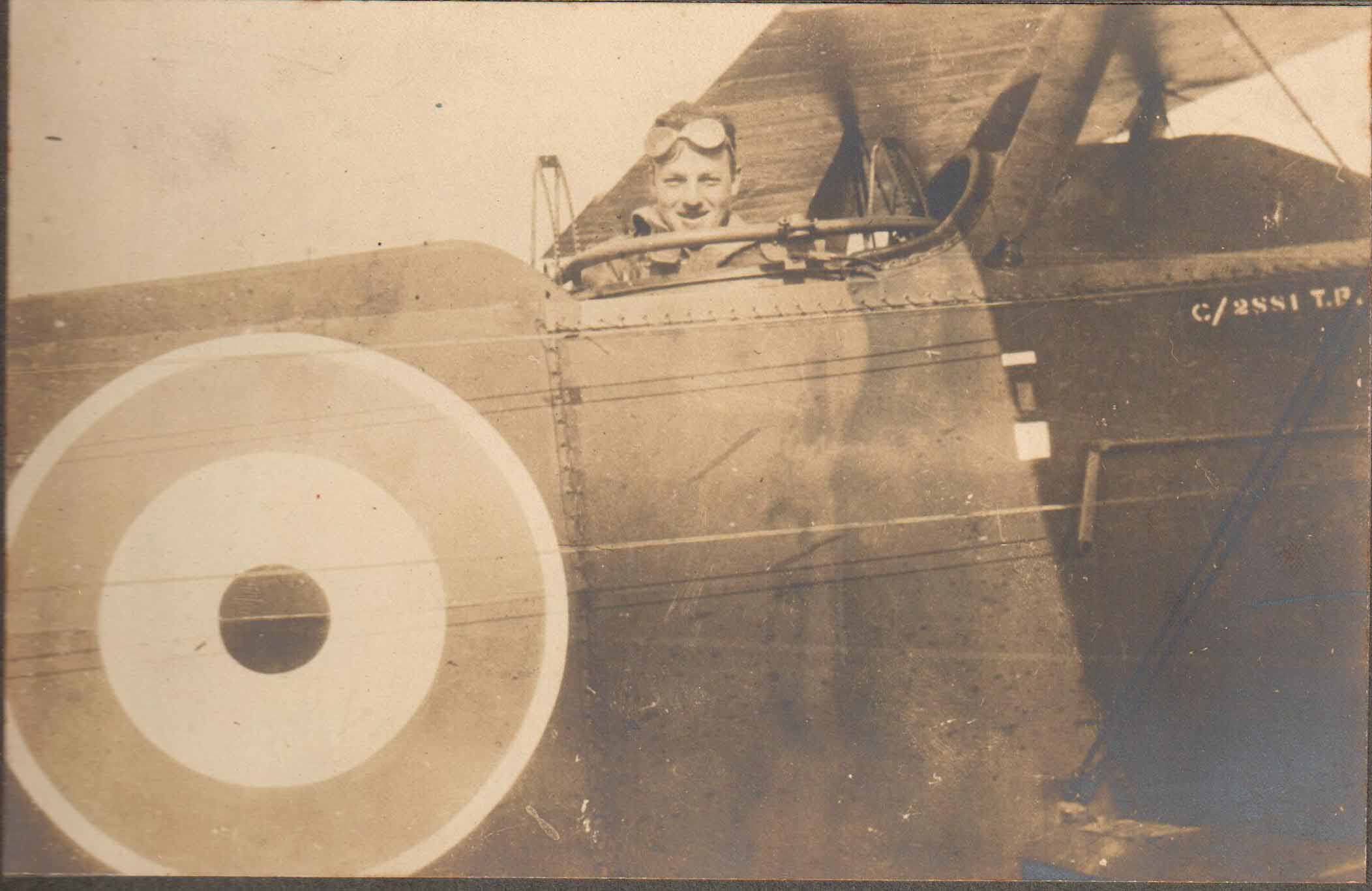

On May 31, 1918, Fleet wrote to Benson: “Am leaving here [Stamford?] today for 5 T.S. Wyton” (Wyton was about fifteen miles northwest of Cambridge).14 A photo taken by Fleet of a Bristol Fighter at No. 9 Training Squadron at Sedgeford in Norfolk suggests he also trained there, and it was perhaps at Sedgeford that a photo was taken of him in an Armstrong Whitworth FK.8.15 He evidently went on to train on DH.4s and was thus among the pilots familiar with that plane when American-built DH-4s began arriving in France.16

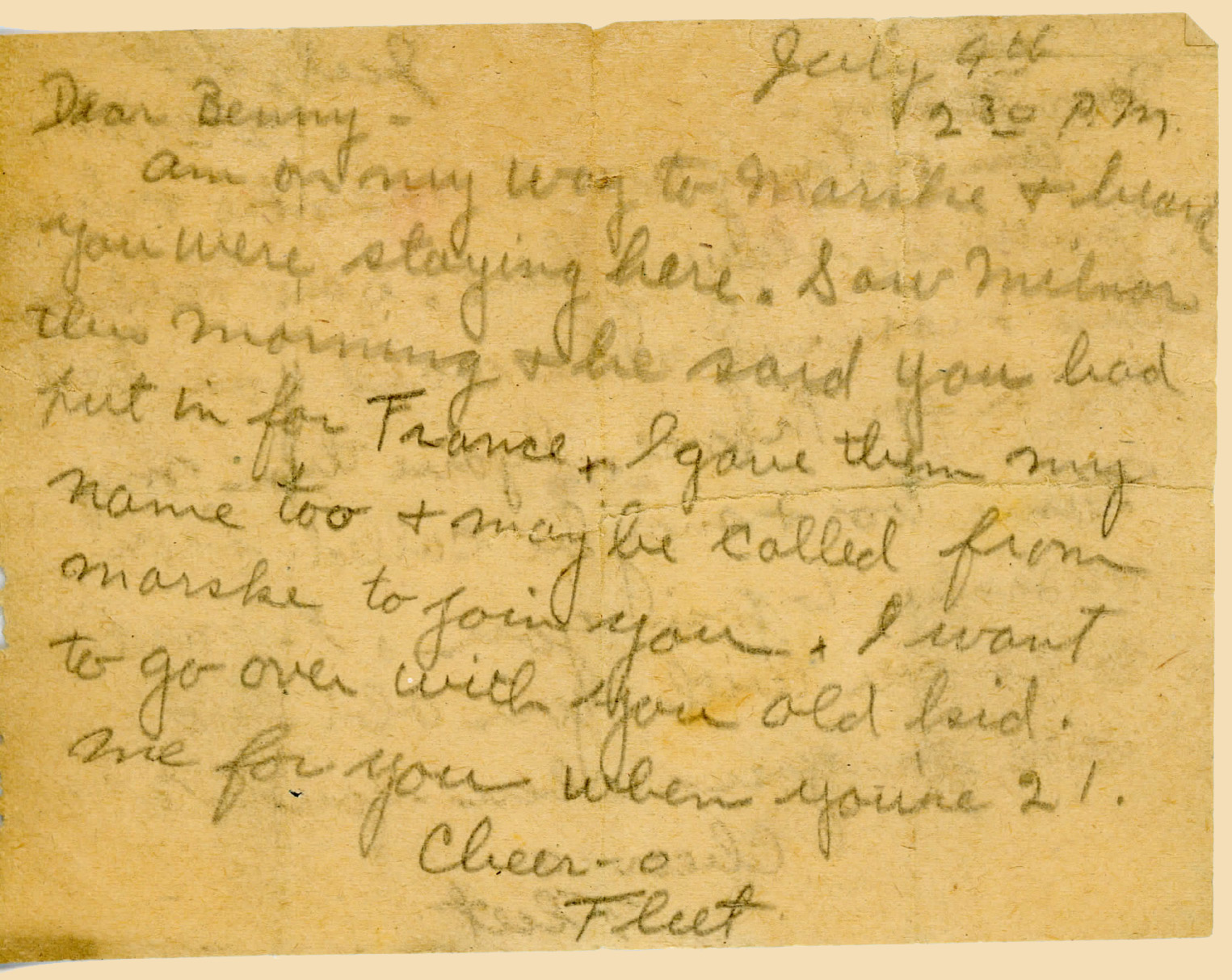

In early July, on his way to Marske, Fleet passed through London, where he ran into Joseph Kirkbride Milnor and left a note for Benson, expressing the hope that they might go to France together.

France and the 135th at Ourches

Fleet, along with fellow second Oxford detachment member Wilbur Carleton Suiter, was in a group of ten British-trained American pilots who in mid-July were ordered to France to fly the new DH-4s. They embarked at Southampton and travelled from Le Havre to Paris.16a From Paris they went to the 3d Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun where, apparently, communications had broken down, and British-trained American pilots were not welcomed or allowed near the new DH-4s.16b Finally, towards the end of July, they were assigned to the U.S. 135th Aero, an observation squadron and the first squadron to fly DH-4s. They arrived at Ourches (a few miles west of Toul), where the squadron was stationed, on July 30 or 31, 1918, and were joined there by two further British-trained American pilots, Robert Donald Likely and second Oxford detachment member Edward Carter Landon.17

Squadron historian Percival Gray Hart describes the early part of August: “These were happy carefree days, when we flew as often as we wanted to: the pilots getting the feel of the new planes; the observers studying their maps. . . . In our spare time we walked to the little nearby villages and learned where the best food and wine could be had; went swimming in the Meuse, right outside the barracks. . . .”18

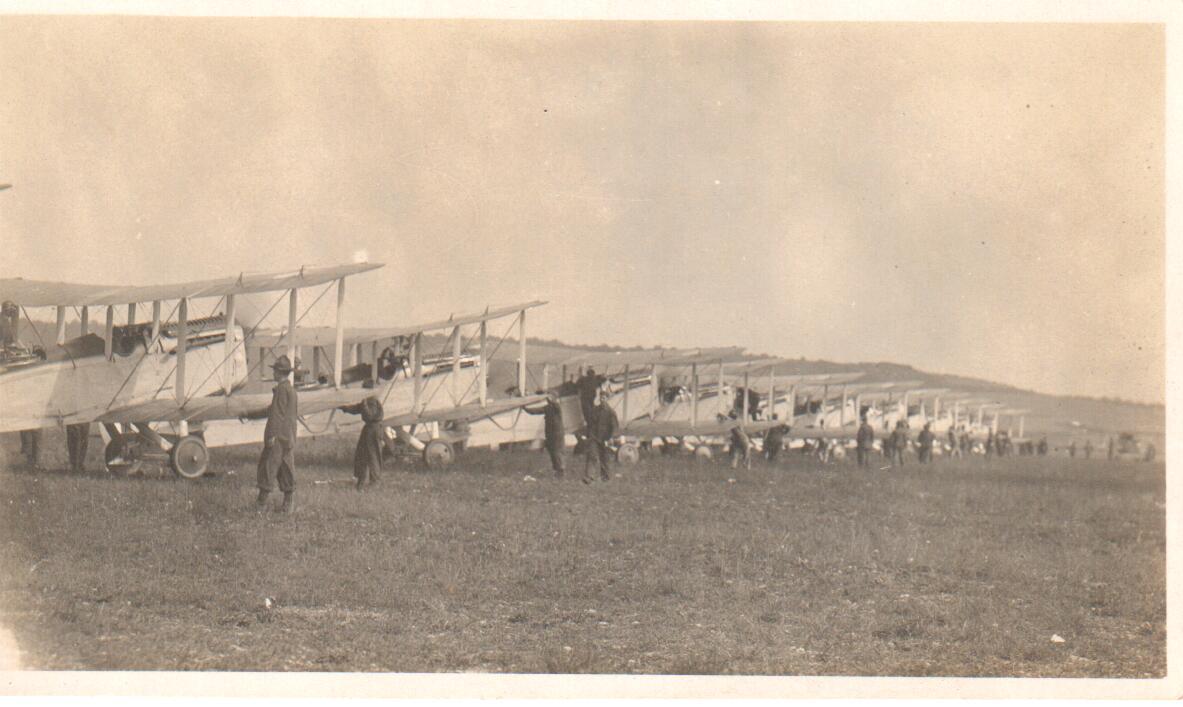

Not long after the arrival of the pilots at Ourches, with much fanfare, the squadron made its first sortie, billed as the “first use made of the DH-4 airplane fitted with the Liberty engine on the western front.”19

Under overcast skies, Alexander Blair Thaw, commanding officer of the 135th, flying with Chief of Air Service Brigadier General Benjamin Foulois, led the flight up through the clouds to execute a large semi-circle and then head home—plans to cross the lines, which could not be discerned due to the cloud cover, having been scuppered.19a The flight was filmed, and can be viewed on footage preserved in the National Archives.20

The squadron settled down to its duties of reconnaissance and photography; they also prepared to perform artillery adjustment (“reglage”), infantry liaison, and counter battery, all of which would be part of their work with the 89th Infantry Division of the American First Army during the St. Mihiel Offensive.21

Fleet was pilot on a memorable photographic mission the afternoon of August 21, 1918; his observer was Richard McDonald Scott, Jr. From 10,000 feet they were to photograph the area between Nonsard and Thiaucourt, about twenty-two miles north of Ourches and about five miles inside the southern edge of the St. Mihiel salient. For protection, Fleet and Scott were accompanied by Lawrence Landon Smart with observer Henry Dale Sheets, and Likely with observer Edward Milton Urband. Urband recounted how, “At 4:45, after making our tour of the Front, and when about to start for home, we sighted three hostile monoplace airplanes with a Pfalz in the lead. At just this time the motor of our ship started to sputter, and the three rapidly approached.” When one of the enemy aircraft was close, Urband “got in a prolonged burst, and he [the enemy plane] sharply spiraled down over Thiaucourt. . . . The two ships broke off combat when their leading ship spiraled down, and fearful that there were others we headed directly for home.”22 Urband and Likely shared credit for the squadron’s first victory, but spirits were dampened by the discovery that the twenty-four photographs taken by Fleet’s observer, Scott, were blank because the cap had been left on the lens.23 “The officer responsible . . . had to buy drinks for the squadron that night.”24 Fleet and Scott attempted a photo mission again late the next morning, but were unsuccessful “on account of engine trouble.”25 On August 23, 1918, in the afternoon, however, flying at about 9,000 feet, Scott was able to make twenty-four exposures between Nonsard and Jaulny (the latter about two miles north of Thiaucourt), of which seventeen were good.26

At the close of his letter to Benson dated August 28, 1918, Fleet remarked that “I have a little job this P.M. only six boxes to take—72 pictures that’s all.” Fleet flew another mission the morning on August 30, 1918; his observer/photographer was Sheets, taking pictures from 12,000 feet between Limey and Broussey, just outside the south boundary of the St. Mihiel salient.26a On September 2, 1918, Fleet, again with Sheets, flew two missions, during the first of which they scrapped with four enemy aircraft; at the end of the day, they had a total of 120 photos, visibility from 12,000 feet having been excellent.27

St. Mihiel and after

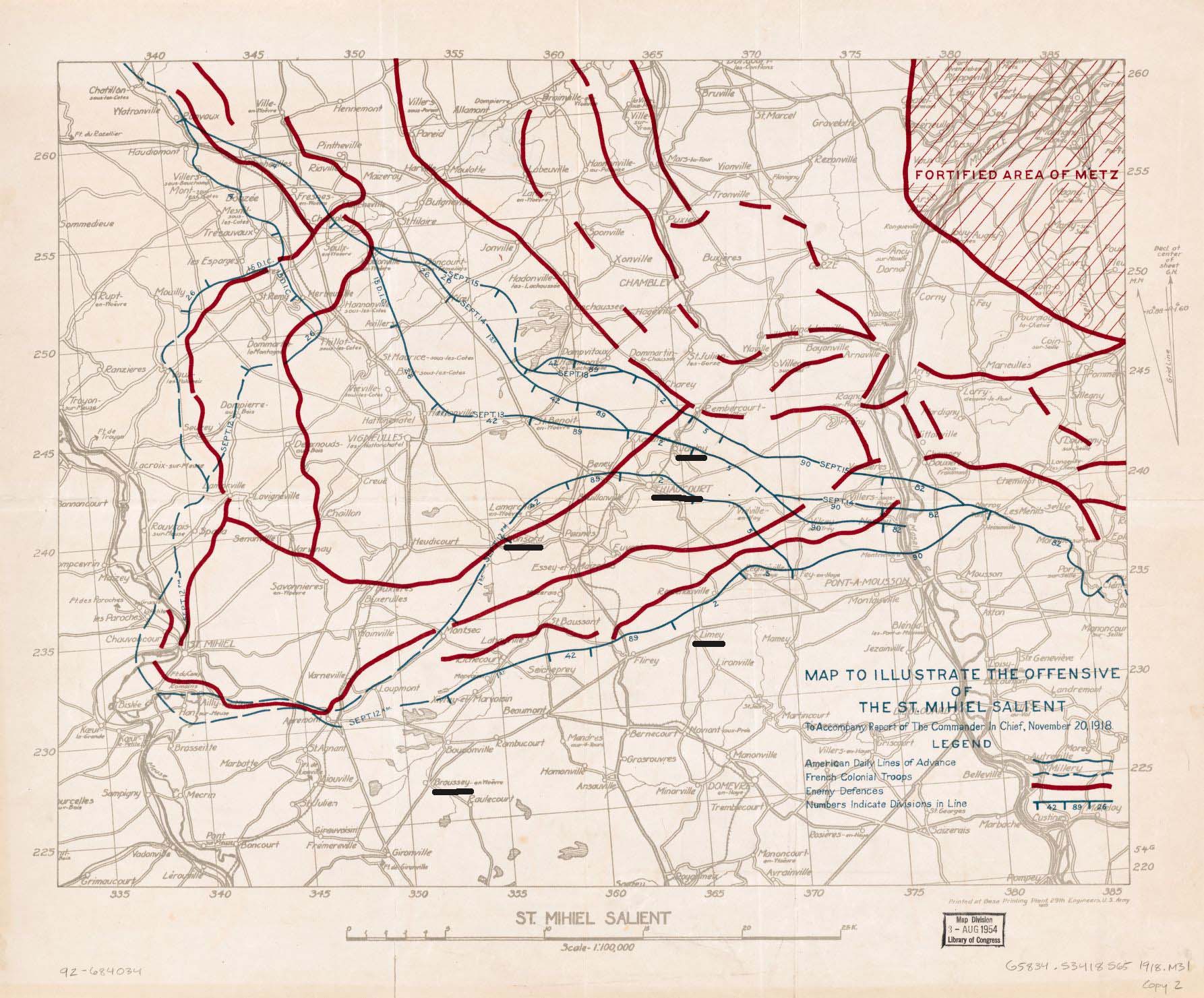

I find no specific information on Fleet’s activities on September 12, 1918, the opening day of the St. Mihiel Offensive, but Hart summarizes by noting that under extremely unfavorable weather conditions “every pilot and observer, . . . had flown twice, and some of them three times.”28 Three teams of pilot and observer did not return to Ourches. One team landed in Switzerland and were interned there; four men were killed, including Fleet’s fellow second Oxford detachment member Suiter.

The following day, September 13, 1918:

Fleet and [Roy Lee] Peck were assigned the first infantry contact mission . . . and took off at 5:30 under considerably better weather conditions. . . . They found the battle still in progress, with the Americans pushing forward, although at a slower rate than on the previous morning. They flew over the road running north from Flirey, which was now the sole artery for supplies, ammunition and artillery for the 89th and 42nd Divisions, and noted the serious confusion and congestion which had inevitably resulted. Then, heading north, they passed over Xammes and Beney and came down to within a few hundred feet of the ground to pick out the exact position of the infantry. Proceeding west they saw the advancing troops of the 1st Division enter Vigneulles at about 6 o’clock and join the 26th Division, which already occupied the town, thus wiping out the [St. Mihiel] salient. Having ascertained this important information they hastened to drop their reports at Division and Corps Headquarters, and then returned to the field with the welcome news.29

Not long after St. Mihiel, the 135th was assigned to work with two additional divisions, the 42nd (“Rainbow”) and the 78th. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which began on September 26, 1918, does not loom large in histories of the squadron. There were plans for them to participate in a “diversionary action to be launched just prior to the jump off in the Meuse-Argonne Forests, which the Army Command hoped would confuse the Germans.”30 “Everyone was assigned to fly twice, with the first planes scheduled to leave before daybreak,” but this was rendered impracticable by fog the morning of September 26, 1918.31 Reports came in that the fog did not extend far, and Fleet, with Hart as his observer, set out at 10:30 “with orders to land at some other field if the fog still enveloped Ourches on their return (if any!).”32 The “if any!” was prompted by reports of Fokkers near the lines. Their reconnaissance, was, however both successful and uneventful. Hart notes that “The visibility was poor next day, but several reglages, one of which was flown by Fleet and Maguire, were completed with the very efficient artillery of the 42nd Division.”32a Otherwise, the “squadron continued to carry on its usual work from September 20th to September 30th.”33

The 135th at Toul

At the end of September the 135th was relocated to Toul, where the men enjoyed better accommodations than at Ourches, as well as the proximity of Nancy; their work remained essentially the same, albeit not always with the same army divisions. On October 11, 1918, Fleet moved up to be commander of A flight, replacing John Joseph Curtin, who had fallen ill and was in hospital.34

Missions were always challenging, but particularly so towards the end of October 1918 when “Fokkers initiated a reign of vigilance along our Front such as we had never witnessed.”35 On October 28, 1918, “Fleet and [Perry Henry] Aldrich, although attacked three times, were able to complete a reglage.”36 On November 5, 1918, Fleet and his observer George Luke Usher provided protection for Leland Durwood Schock and his observer Otto Earl Bennell as they undertook a photographic mission. They were attacked just as they completed it. Returning fire, they shot down one enemy plane, and the four men shared credit for the victory.37 Six days later, the squadron celebrated the armistice at the Liegeois Café in Nancy.38 Brief film footage, in which Fleet, Schock, Bennell, and others (but not Usher) can be identified, was shot during the period when the 135th was in Toul, and there are a number of commemorative still photos from the same period.39

Fleet was able to return home relatively quickly; he sailed from Brest on the Canada on January 10, 1919, and arrived at Boston January 21, 1919. His shipmates included fellow officers from the 135th (Cole, Wallace Angus Coleman, Landon, Schock, and Smart) and two men from the second Oxford detachment who had been prisoners of war (Alexander Miguel Roberts and Horace Palmer Wells).40

After his discharge from the army (January 30, 1919) Fleet for a time joined his brothers in managing his (deceased) father’s furrier business.41 Later he and his family moved to Florida where he operated a hotel.42

mrsmcq July 5, 2017; revised October 10, 2019, to provide more information on late August 1918 missions; revised October 31, 2022, to reflect letters to Benson

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For his place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Charles C Fleet. His date and place of death are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963, record for Charles C Fleet. It should be noted that Fleet has at times been mistaken for Croix de Guerre recipient Charles M. Flett of the 9th Balloon Company; see “90th Aeronaut Co. / Charles Carvel Fleet.” The photo is a detail from a group photo of Squadron 7 at the Ohio State University School of Military Aeronautics.

2 See Wikipedia, “Francis Wyatt”; Newman, The Flowering of the Maryland Palatinate, pp. 204-09; and documents available at Ancestry.com, including Sons of the American Revolution applications.

3 See “William Hamilton Fleet” as well as documents available at Ancestry.com.

4 Fleet’s name appears in a list of competitors for a March 1911 interclass track meet on p. 75 of the 1911 Polyglot and in a roster of 1911-1912 cadets on p. 65 of the 1912 Illustrated Catalogue of the Culver Military Academy.

5 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

6 Foss, Diary, October 13, 1917.

7 Deetjen, Diary, October 4, 1917.

8 Foss, Diary, October 14, 1917; Deetjen, Diary, October 14, 1917. Vaughn recalled that “our West Point trained U.S. Army superiors had a standing penalty for violation of discipline—the threat to transfer us to France to join the groups who were building barracks in the mud at Issoudun” (Vaughn War Flying in France, p. 23). Springs, writing to his stepmother in mid-October 1917 describes the challenges of keeping his men in line, noting that “the dire punishment I threaten them with is to have them sent over to France. And it works too.” (Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 40.)

9 Foss, Diary, November 14, 1917.

10 See Chalaire, “Thanksgiving Day with the Aviators Abroad.”

11 See Foss, diary entry for November 30, 1918; and Foss, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” (in Foss, Papers). See also Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 18, 1917.

12 These are among Fleet’s war year photos, now in the possession of his daughter, Ruth Ann Fleet Thurman. My thanks to her, and also to her daughter-in-law, Gaelynn Thurman, who provided copies.

13 Cablegrams 874-S (on the recommendation “non flying” in the cablegram, see here) and 1303-R (the latter dated May 13, 1918).

14 The letter is in Benson, Leslie A. A. Benson Collection, 1917-1919.

15 Percival Gray Hart, in his History of the 135th Aero Squadron, includes an otherwise unexplained photo of the Sedgeford aerodrome (photos after p. 90), and Donald B. Cole, who joined the 135th at the same time as Fleet, recalls training at No. 110 Squadron at Sedgeford (“Memoirs of Lt. Donald B. Cole,” pp. 153-54). Sedgeford thus appears to have been an important station for some pilots of the 135th.

16 Conventionally “DH.4″ refers to the British built, original version of the plane, “DH-4″ to the American built plane with the “Liberty” engine.

16a Smart, The Hawks that Guided the Guns, p. 24, lists the ten men (including himself) in the group embarking at Southampton. The names correspond to the identifications of men described as the “Original complement of the 135th Aero Squadron pilots on the way to the Front” reproduced on p. 160 of Cole’s “Memoirs of Lt. Donald B. Cole.” The ten were James Ernest Bowyer, Donald Brown Cole, Wallace Angus Coleman, John Joseph Curtin, Fleet, Lucius Warren Guernsey, Walker Marshall Jagoe, Leland Durwood Schock, Lawrence Landon Smart, and Suiter.

16b See Smart, The Hawks that Guided the Guns, pp. 24-25, and Cole, “Memoirs of Lt. Donald B. Cole,” p. 154, on the journey and the reception at 3 A.I.C. Dwyer, “Memorandum No. 8 for Flying Officers,” p. 4, provides a list of men, including Fleet, at Issoudun at this time.

17 Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, pp. 21 and 23, indicates that pilots, including Fleet, and planes arrived on July 30, 1918; this is also the date provided by Likely, whose account may have served as a source for Hart. Fleet in his letter to Benson, gives the date July 31, 1918. Smart, The Hawks that Guided the Guns, p. 28, remarks that at Ourches were “two other English-trained pilots, Ed Landon and Charlie Fleet, whom we did not know.” I take this to be a slip of the pen and that for Fleet we should read Likely. Inexplicably, Fleet’s name appears nowhere in the history of the squadron written by Bradley J. Saunders, Jr., the squadron’s commanding officer from mid-August 1918, nor in the appended roster.

18 Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, p. 30.

19 Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p. 88. Maurer goes on to state that this flight took place on August 2, 1918. Maurer’s source for the (incorrect) date was presumably Patrick’s Final Report, p. 41. Photographs and movie footage taken at the time, as well as the accounts by Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, pp. 31-33, and Smart, The Hawks that Guided the Guns, pp. 35-36 and 39, indicate that the flight, with fifteen planes, took place August 9, 1918. Saunders, History of the 135th Aero Squadron (Observation), p. 65, gives the date August 7, 1918; Fleet in his letter to Benson writes “We crossed the lines six days after getting our machines,” which would indicate August 6, 1918. Maurer and Saunders both mention a flight of eighteen planes.

19a Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, p. 32.

20 For the film footage, see “Aviation Activities in the A.E.F., Miscellaneous Scenes [1918]”; for a “shot list,” see “Aviation Activities in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF).”

21 For details of these activities, see Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, pp. 34 ff.

22 This mission is described on p. 48 of Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, which includes a passage from Urband’s log book.

23 Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, p. 48.

24 Smart, The Hawks that Guided the Guns, p. 43.

25 Headquarters, Detachment First Army, Air Service, American E.F., “Operations Report No. 128,” first page.

26 Headquarters, Detachment First Army, Air Service, American E.F., “Operations Report No. 129,” first page. (Note: Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, p. 49, implies that this successful effort occurred on August 22, 1918.)

26a Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, p. 54; “Outline for a History of the 135th Aero Squadron,” entry for August 30, 1918.

27 Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, pp. 56–57.

28 Ibid., p. 73.

29 Ibid., p. 74.

30 Smart, The Hawks that Guided the Guns, p. 50.

31 Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, p. 93.

32 Ibid., p. 94.

32a Ibid., p. 98.

33 Saunders, History of the 135th Aero Squadron (Observation), p. 68.

34 Hart, History of the 135th Aero Squadron, pp. 116-17.

35 Ibid., p. 130.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid., pp. 148 and 180.

38 Ibid., p. 154.

39 “Aviation Activities in the A.E.F., Miscellaneous Scenes [1918]”; see “Aviation Activities in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF)” for a shot list.

40 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for detachment of casual officers on Canada.

41 Ancestry.com, U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963, record for Charles C Fleet, provides his army discharge date. Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Charles C Fleet, records his post-war occupation.

42 Ancestry.com, 1940 United States Federal Census, record for Charles C Fleet.