(Lynnville, Tennessee, February 26, 1894 – near London Colney, Hertfordshire, England, May 4, 1918).1

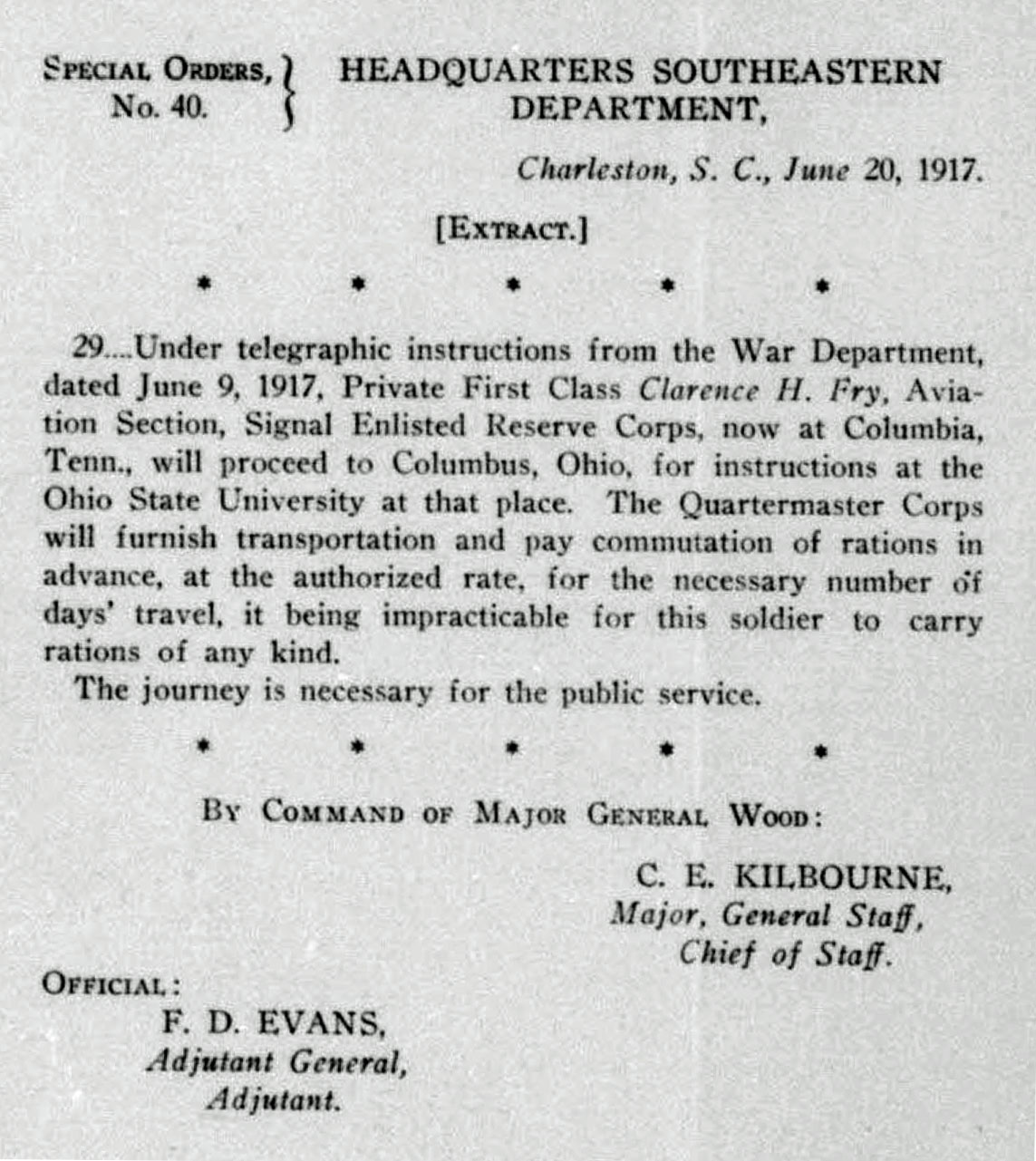

Fry was the second youngest of six children of a prominent businessman in Columbia, Tennessee; his mother died when he was eleven. He attended Columbia Military Academy, graduating in 1912. He and his brother Charles Carlton Fry started an automobile business, “Fry Brothers,” in Columbia, and Clarence was involved in the running of it through the early summer of 1917.2 He noted on his draft registration (dated May 28, 1917) that he had an “application in for aviation service.”

Fry attended ground school at Ohio State University, graduating August 25, 1917.3 He was one of the eighteen men from this class at O.S.U. who chose or were chosen to train in Italy and thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment.” The detachment sailed to England on the Carmania, departing New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departing Halifax as part of a convoy on September 21, 1917. During the Atlantic crossing, a fellow detachment member, Parr Hooper, wrote: “Tonight after supper I had an interesting confab on the upper deck with Clarence Fry, the typical story-book Southerner. He corrected some of my barbarous ideas of what was the proper way to act towards the Germans during the war, and taught me some chivalry.”4 Two days later, the convoy entered dangerous waters, and men were ordered to assist with submarine watch. Fry and Fremont Cutler Foss watched at the bow for two hours before dawn, from 9 to 11:00, and again from 3 to 5 p.m. on September 29, 1917. By late in the evening of October 1, 1917, the ship had passed out of danger, and Foss reports that “Dietz, Forster, Deetjen, Neil [sic; sc. Nial], Hagan, Fry and many others had a feast with food prepared for the guard which was called off at 9:30. Twenty loaves of bread and about twenty pounds of meat were ruined.”5

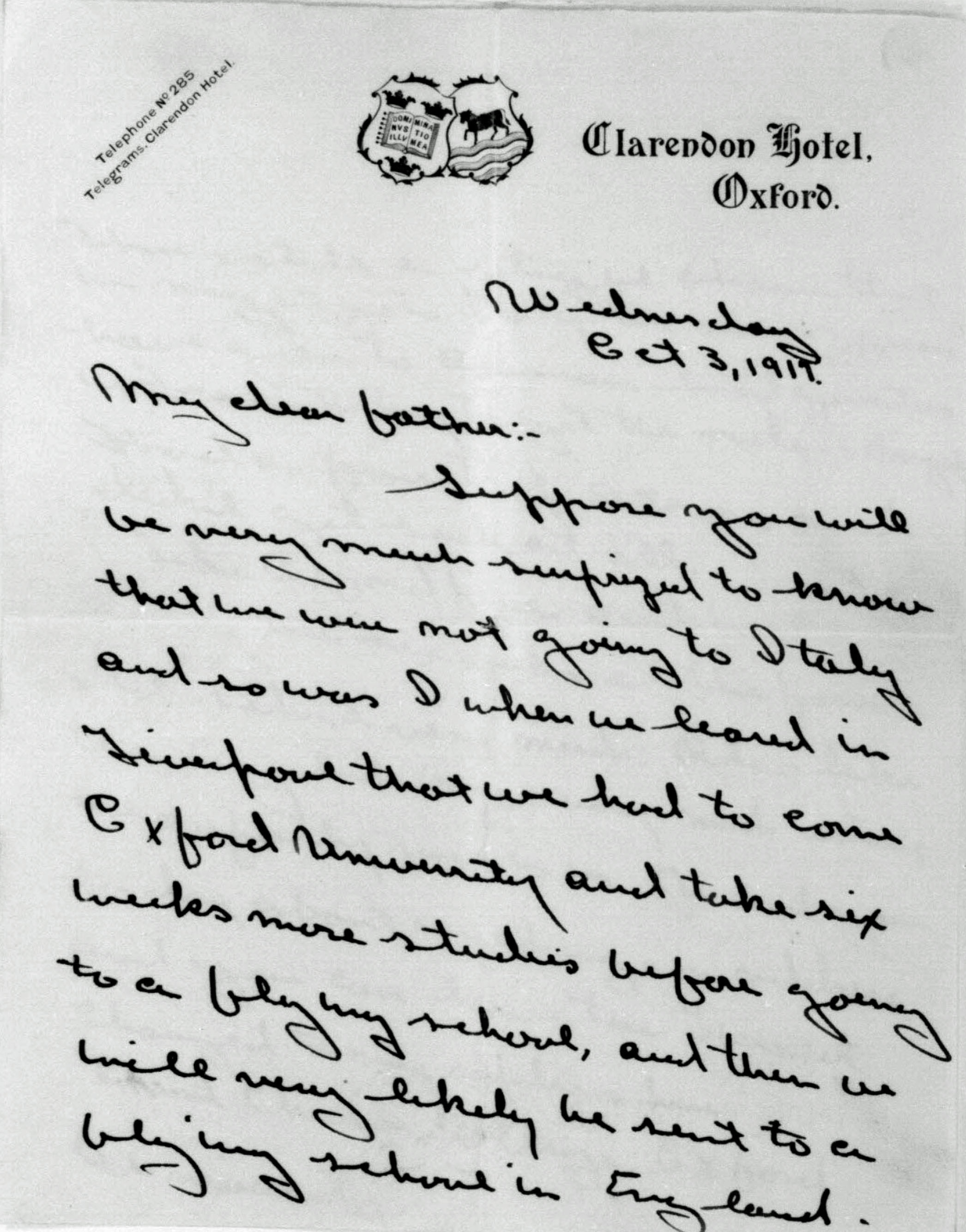

The Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. The next day Fry wrote to his father: “Suppose you will be very much surprised to know that we were not going to Italy and so was I when we learned in Liverpool that we had to come [to] Oxford University and take six weeks more studies before going to a flying school and then we will very likely be sent to a flying school in England. . . . Like Oxford and will enjoy the six weeks at the famous old school very much.”6 The War Birds diarist remarked that “Fry, Curtis, Cal, Brown, and I took a bicycle ride over to the Duke of Marlborough’s palace at Woodstock.”7 A month later, on November 3, 1917, Fry travelled with most of the detachment to Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gun school.

In mid-November fifty of the men at Grantham were selected to go on to flying schools, and Fry was one of the ten assigned to Thetford in Norfolk.8 The November 17, 1918, entry in War Birds reads in part: “Cal, Curtis, Brown, Fry and I are ordered to Thetford to learn to fly at last. This is the final bust-up of the Italian Detachment.” Fry apparently roomed with John McGavock Grider and Laurence Kingsley Callahan and was acquring a reputation as a humorist: “Fry is in the same room with us and is terribly funny.”9 By December 3, 1917, Fry was able to report that he had

been doing a great deal of flying for the past few days and will start flying by myself (solo) in another day or two. I have a new instructor now that is awfully hard to please but think I am doing very well. He invited me to go to a neighboring town with him yesterday to take lunch and return in the afternoon. I flew the machine all the way over there and back and enjoyed the trip very much. Climbed up to six thousand feet, then flew straight to the town, using the railroad track as a guide, and landed in another airdrome.

In the same letter he wrote that a “Mr Fisher and his wife who live near here and own the land this airdrome is on had Callahan and myself to dinner Thursday night.”10 He and Laurence Kingsley Callahan had evidently been the guests of the very wealthy Cecil Vavasseur Fisher and his American born wife at Kilverstone Hall just outside of Thetford.

Fry apparently had his first challenging attempt at flying solo not long afterwards, but by December 18, 1917, was able to report: “I started flying solo again early this morning and finished over half the time I have to do here and will finish entirely tomorrow and be sent on to an advanced squadron. I put in most all day flying and made ten landings and only broke one skid wheel, which I consider pretty good for a beginner, inasmuch as I had such hard luck the first time I went off solo.”11 The War Birds diary entry for January 1, 1918, notes that “Fry wrote off a bus by pancaking from 200 feet”; perhaps this was the “hard luck” of Fry’s first solo.

Around the turn of the year Fry went to No. 74 Training Squadron at London Colney. Hooper took a photo there on January 3, 1918, of four men standing in front of an Avro , with the caption “Fry, Curtis, Brown, and Anderson,” and Hooper remarks in a letter of January 8, 1918, written from 56 T.S. at London Colney that “Fry and Stillman are nearby at #76 [sic; sc. 74].”12 While still at Thetford, it appears that Fry had joined Grider and Callahan on at least one trip to London, and such outings were easier to make now that he was billeted, along with fellow detachment members Marvin Kent Curtis, Conrad Henry Mathiessen, Austin Finley Morrison, Joseph Frederick Stillman, and Glenn Dickenson Wicks, at the Red Lion Inn in Radlett where, as Curtis wrote, “we are nearer London . . . in fact can get in by bus, and then tube.”13 There was also pleasant socializing locally: in mid-March Curtis notes that “we have met some very nice people in town here and have been invited (Clarence Fry and I) out to tea and dinner several times.”14

Among the friends made in Radlett were the families of Dr. Percy Ewart Bowles and Lt. Col. John Wakefield Rainey.15 Also in mid-March Fry enjoyed a much anticipated visit from his brother William McCreary Fry, who was serving as an army field clerk in France.16

Fry’s training apparently paralleled that of Curtis. Curtis did his cross-country flight on an Avro on February 27, 1918, “thus completing all tests for graduation to the one seater scouts.”16a The next day Fry, along with Jesse Frank Campbell, did the same. Campbell wrote in his diary that day: “Fry and I did our cross country trip today. Since I had been to Northolt before, I was elected leader. We ran into a snow storm after leaving Northolt and got lost, landed at Brooklyns [sic; sc. Brooklands?] and after getting our bearings arrived safely at Hounslow.” In early March, when 74 became operational and left for France, Fry transferred to No. 56 T.S., also at London Colney, and presumably moved on to Sopwith Pups. In a letter home on March 29, 1918, he describes “practicing trench strafing” and then, when a rocker arm broke, being forced to land in a very small field, “so small that they had to take the machine to pieces to get it out. The commanding officer of the squadron congratulated me on the good show I made in not crashing my machine.”17 However, perhaps because of censorship rules, Fry here and elsewhere does not indicate what type of plane he was flying.

Fry graduated from this phase of his training around April 5, 1918 (the day Pershing forwarded the recommendation—“which has been in for some time”—for Fry’s commission to Washington).18 On April 12, 1918, Fry wrote his sister Minnie that he was “in Torquay in Devonshire . . . spending my four days graduation leave.”19 On his return to London Colney, Fry advanced to practicing aerial fighting: Curtis’s pilot’s flying log book has an entry for April 22, 1918, “Aerial fighting w. Fry”—Curtis was flying Sopwith Pup [B]7482. Five days later, Curtis had his first flight in a Spad, and Fry presumably also advanced to Spads around this time as well.

Both Fry and Curtis had since March anticipated being sent to Scotland “for a short fighting course,” but they were still at London Colney on May 4, 1918, when Fry took up Spad A9132.20 Barksdale, who was also at 56, describes what followed:

About 5 o’clock Clarence H. Fry of Tenn (Nashville?) was doing a climbing turn on the take off in a Spad & climbed to [sic] long & steep where the machine stalled & dropped nose down to the ground where he was killed instantly. His neck, right leg & arm was broken was cut up pretty bad [sic]. Engine was buried in the hard ground. He had finished flying Spads & was only taking a joy flip while waiting to go to Ayr.21

Camels acquired a deserved reputation among the men as dangerous, but it is worth noting that, according to calculations made by Geoffrey James Dwyer of the American Aviation Office in London after the war, the casualty rate per hours flown was higher for Spads than for Camels.

Elliott White Springs, in a letter to his stepmother written May 7, 1918, wrote: “Clarence Fry of Columbia, Tennessee, was killed Saturday and I wish you would send a letter of sympathy to his people. He was a particularly good friend of mine and an exceptionally fine fellow—clever, amusing, and with the heart of a lion. The whole Italian Detachment mourns his loss.”22 Grider wrote his friend Emma Cox that “I lost one of my best friends last week, a boy named Clarence Fry from Columbia, Tennessee. . . . Poor fellow, one of the very best. If you see any of his folks, tell them he was ace high over here and one of the most popular men in the outfit.”23

Fry was given a full military funeral and was buried in the cemetery at St. Albans on May 7, 1918.24 Curtis wrote his (Curtis’s) sister Josephine the next day that “I was feeling pretty rotten after poor old Fry’s funeral yesterday, so they gave me two days leave and I came down here [Lynton, North Devon] to rest up. . . . Fry was killed last Saturday. It was a great blow to all of us—but to me especially I think, because we had been pretty close friends since November first. . . .”25 In another letter to Josephine, Curtis wrote that Fry’s “brother came over from France and I made sure that some of his personal belongs and pictures etc. would be preserved.”26 William McCreary Fry wrote his father about this sad undertaking in a letter of May 13, 1918: “I have been out to his grave. It is simply covered with flowers.”27 In the meantime Fry’s commission had been confirmed in a cable date that same day.28

After the war, in August 1920, Fry’s body was reinterred in Rosehill Cemetery in Columbia, Tennessee.29

mrsmcq July 17, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Fry’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Clarence Horne Fry. The photo is a detail from a group photo of Squadron 7 at the Ohio State University School of Military Aeronautics.

2 On Fry’s family background and his father, see “John W. Fry.” On his early years, education, and business activities see “Lieutenant Clarence Horne Fry, R.F.C.,” p. 156.

3 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

4 Hooper, Somewhere in France, entry for September 26, 1917.

5 Foss, Diary, entries for September 29 and October 2, 1917.

6 Fry, letter of October 3, 1917, in Fry, [Papers, memorabilia].

7 Entry for October 3, 1917, which is evidently a catch-all entry that records events of the early part of the men’s time in Oxford.

8 See Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917.

9 War Birds, entry for November 20, 1917

10 Fry, letter of December 3, 1917, in Fry [Papers, memorabilia]. Fry’s letters are excerpted in “Lieutenant Clarence Horne Fry, R.F.C.”

11 Fry, letter of December 18, 1917, in Fry [Papers, memorabilia].

12 The photo appears after Chapter 5 of Hooper, Somewhere in France; that chapter includes the letter of January 8, 1918.

13 War Birds, entries for December 6, 1917, and January 24, 1918; Curtis, letter of January 19, 1918.

14 Curtis, letter of March 18, 1918.

15 See Bowles’s letter in “Letters from England” in Fry, [Papers, memorabilia], and Curtis, letter of May 3, 1918.

16 See Fry’s letters of February 26 and March 1, 1918, as well as William Fry’s notes on his visit, in Fry, [Papers, memorabilia]. On William Fry’s military status, see War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Outgoing Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Army Field Clerks, on Aurania, sailing October 3, 1917, from New York.

16a Curtis, letter dated February 27, 1918, to his sister.

17 Fry’s letter of March 29, 1918, in Fry, [Papers, memorabilia].

18 On his commission see Fry’s letter of March 29, 1918, in Fry, [Papers, memorabilia], and cablegram 858-S.

19 In Fry, [Papers, memorabilia]; see also Curtis, letters of April 9 and 13, 1918,

20 Fry anticipated going to Scotland in a letter dated March 29, 1918, in Fry, [Papers, memorabilia]. See also Curtis, letters of February 5 and 27, March 18, April 24 and 28, and May 3, 1918.

21 Barksdale, “Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry for May 4, 1918. See also “Fry, C.H. (Clarence Horn),” the incident casualty card related to Fry’s accident. I find no record of a court of inquiry related to his death.

22 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 122. It is odd that in War Birds, Fry’s death is reported in the entry for May 11, 1918, but perhaps Springs was relying on newspaper articles, which reported the death in editions of that date. Among the letters of condolence to Fry’s family are one from Curtis and a joint one from Wicks and Jesse Campbell.

23 Grider and Jacobs, Marse John Goes to War, p. 92.

24 “Lieutenant Clarence Horne Fry, R.F.C.,” p. 158. See also “Fry, Clarence H.” Barksdale, diary entry for May 7, 1918, supplies the date.

25 Curtis, letter of May 8, 1918.

26 Curtis, letter of May 31, 1918.

27 “Letters from England,” in Fry, [Papers, memorabilia].

28 Cablegram 1303-R.

29 “Lieutenant Clarence Horne Fry, R.F.C.,” p. 158.