(Auburn, Maine, July 27, 1886 – Wayne Township, Kosciusko County, Indiana, August 25, 1921)1

No. 104 Squadron I.A.F. ✯ 166th Aero Squadron

Merrill’s father, Charles Alphonso Merrill, was apparently descended from the Nathaniel Merrill who emigrated from Suffolk, England, to Massachusetts in the 1630s and whose great-grandson, James Merrill, settled in New Gloucester, Maine, in the 1740s. Merrill’s mother, born Fenella Eliza Dearborn, had similarly deep family roots in New England, as she was probably descended from Godfrey Dearborn of Devon, who settled in New Hampshire in the early seventeenth century and some of whose descendants then moved to Maine.2

The town of Auburn in south-central Maine where Merrill was born was a center of shoe manufacturing, and it was in this industry that Merrill’s father was employed for much of his life, before he went into farming. Linn Daicy Merrill was the second of four children. I find no record of his having attended college. In 1903 and 1904, when he was still high school age, he was an infantry private in Maine’s National Guard.3

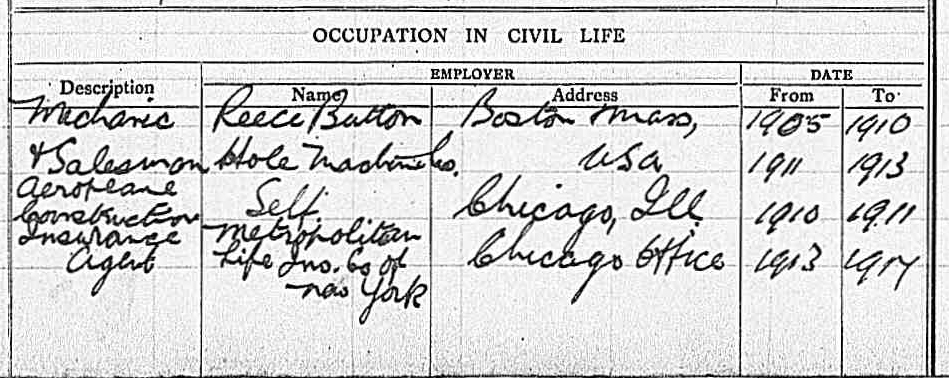

From 1905 until 1910, according to notes on his R.A.F. service record, Merrill worked as a mechanic at the Reece Button Hole Machine Company in Boston; in 1910 he moved to Chicago, where he worked as a salesman for the same company.4 His R.A.F. service record also notes that in 1910 and 1911 he tried his hand at “aeroplane construction.” In early 1911 Merrill married Leonilda Barbara Manfroi, the Danish-born daughter of an Italian stonecutter and his Danish wife who had emigrated with their children to Chicago in about 1900.5 From 1913 through June 1917, when he registered for the draft, Merrill worked as an insurance agent in Chicago.6

Merrill’s earlier interest in airplane construction was presumably a factor in his applying for and being accepted by the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. He began ground school at the University of Illinois at Champaign in early July 1917, the month when he would turn thirty-one—the caption of a photo of him from late in the war indicates he was known as “Grandpa,” and, indeed, he was one of the oldest, if not the oldest of the men of the second Oxford detachment.7

Merrill’s ground school class of about thirty men graduated September 1, 1917.8 Most of them, including Merrill, chose or were chosen to go to Italy for flying training and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed from New York for Europe on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania. After a brief stopover at Halifax the Carmania joined a convoy for the voyage across the Atlantic. The men sailed first class and enjoyed some leisure, including concerts featuring the violinist Albert Spalding, who was on board. They also had Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, and, once they entered dangerous waters, they took turns at submarine watch. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment members learned that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England for their training. They travelled by train to Oxford, where they spent the month of October repeating ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics.

In early November twenty of the men were selected to start flying training at Stamford, but the rest of them, including Merrill, were assigned to machine gunnery school at Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire; the R.F.C. did not have sufficient openings at training squadrons for all the men eager to begin instruction. Places opened up in the middle of November for fifty men, but, again, Merrill was not among those selected, and he remained at Grantham through Thanksgiving and the end of the month.

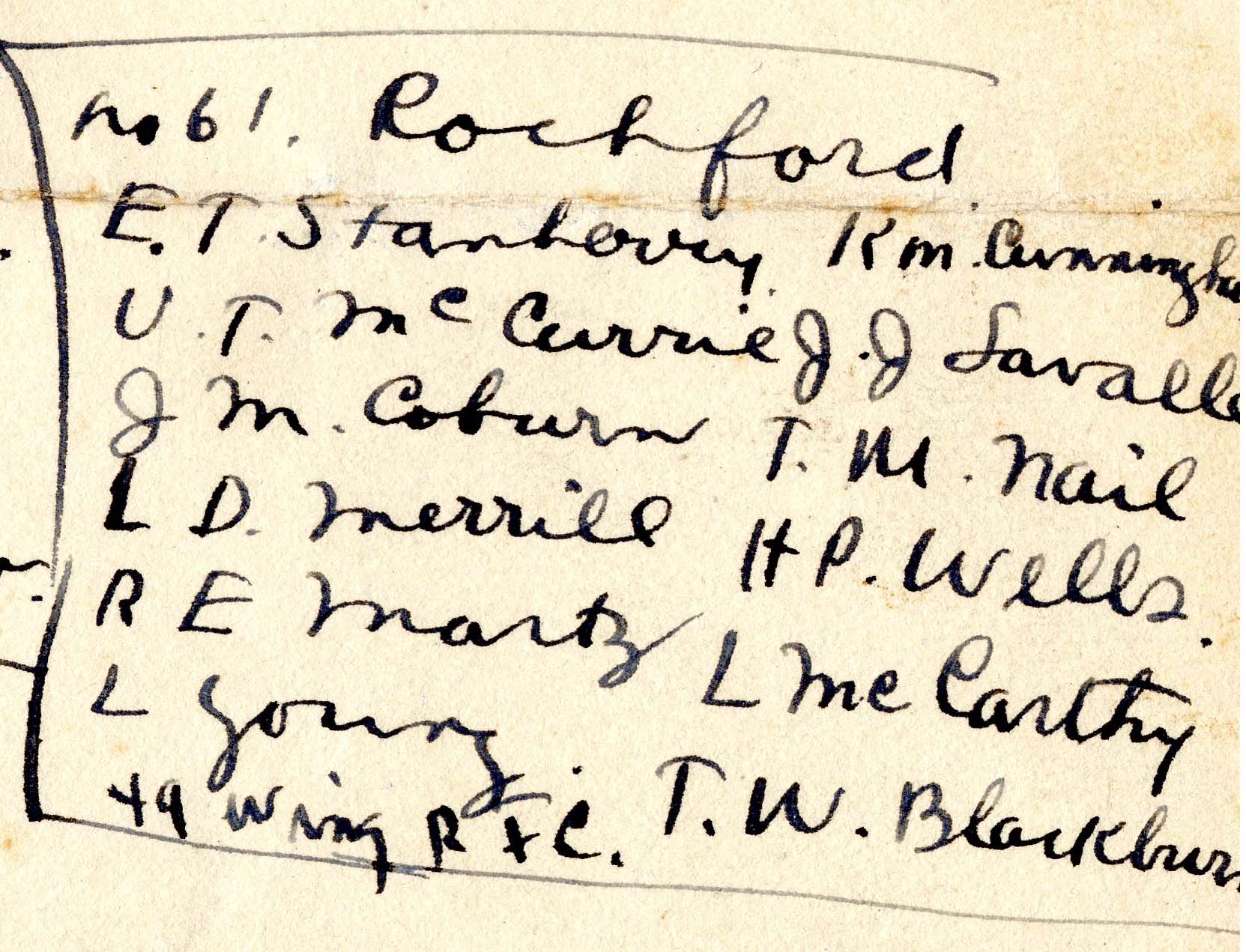

Finally, on December 3, 1917, the remaining men at Grantham were assigned to squadrons. Merrill was in a group of twelve posted, at least initially, to No. 61 Squadron, a home defense squadron in Rochford in Essex.9 Some of them, or perhaps all, were quickly reassigned to No. 198 Night Training Squadron, which shared the airfield with No. 61 and which had Avros for training purposes.10 If Merrill was among those reassigned, then, judging by the account of his fellow detachment member, Uel Thomas McCurry, he would have received extensive initial training at No. 198.11

Merrill’s R.A.F. service record, without providing dates, documents some of his further training assignments, including “6 TDS,” i.e. No. 6 Training Depot Squadron at Boscombe Down just outside Amesbury in Wiltshire; this was one of the main training locations for daylight bomber pilots. Some of the Rochford men are documented has having been assigned to 6 T.D.S. on January 26, 1918, and it seems likely that Merrill also was assigned to Boscombe Down on that date. He was one of six in the Rochford group who were recommended for their commissions on February 16, 1918—well before the majority of the detachment members.12 His service record notes: “since joining R.F.C. Flown AW (Big), DH4 & 9 (BHP),” i.e., the Armstrong Whitworth FK8, the DH.4 and DH.9 with a Beardmore-Halford-Pullinger engine; all of these were two-seater aircraft used operationally for reconnaissance and bombing and available for use in training at Boscombe Down.

Merrill probably trained at Boscombe Down for three or four months.12a Once his work there was finished, he took an aerial gunnery course at Turnberry on the west coast of Scotland and a course in wireless telephony at Chattis Hill in Hampshire; his R.A.F. service record then notes that he served for a time as a ferry pilot in England.

No. 104 Squadron I.A.F.

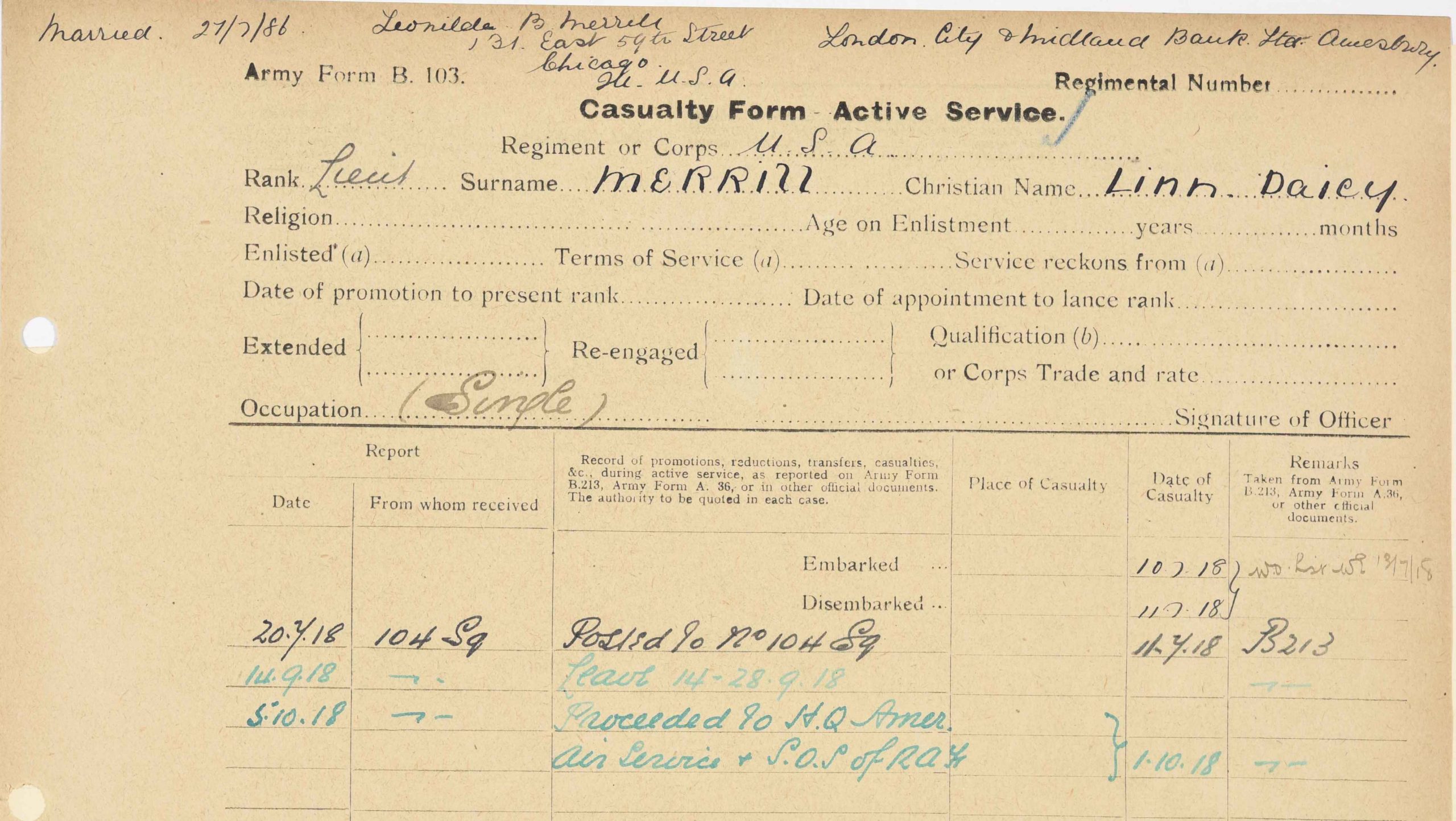

In early July 1918 Merrill was among a large group of American pilots ordered to proceed from London to the 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun in the Loire region of central France.13 From there he was posted on or about July 11, 1918, to No. 104 Squadron, a day bomber squadron of the Independent Air Force.14

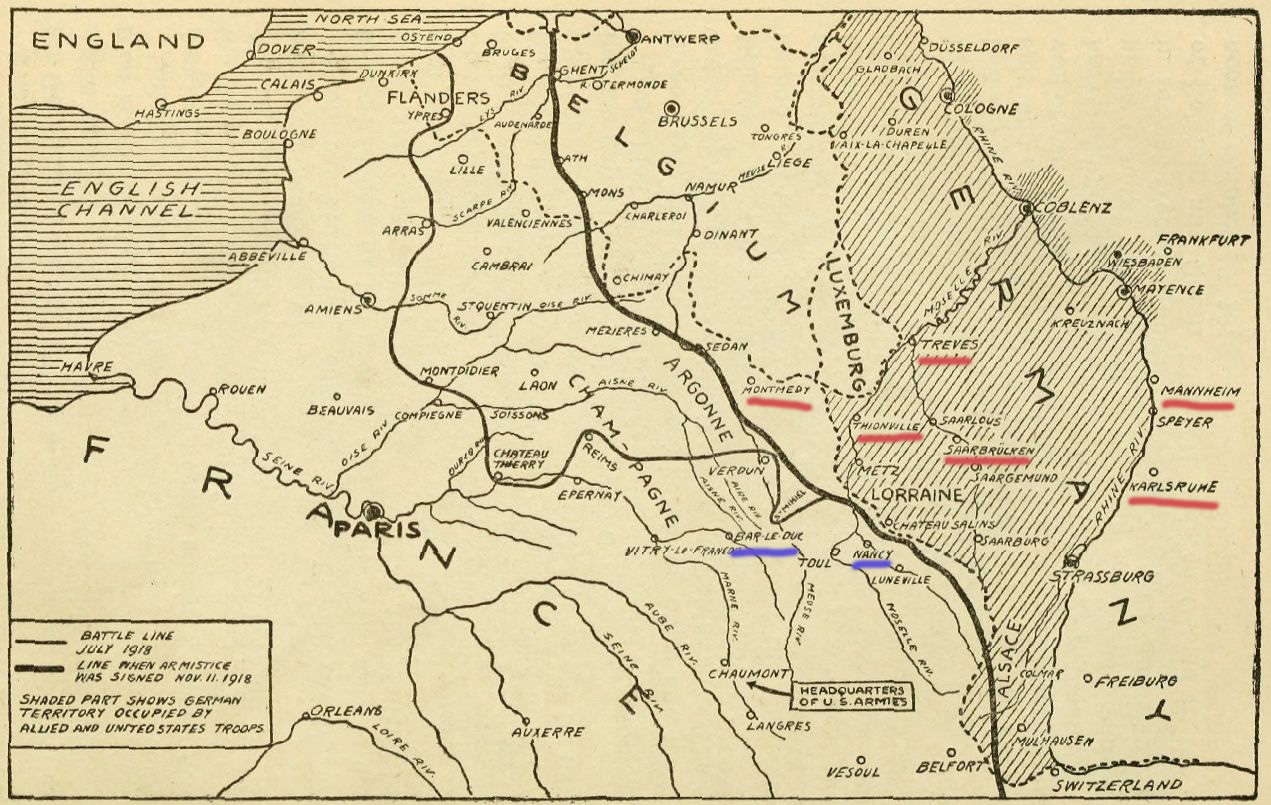

No. 104 flew DH.9s and was one of the four long-range day bomber squadrons of the I.A.F. (the others were 99, 55, and, eventually, 110) stationed at Azelot, a few miles south of Nancy. The I.A.F., commanded by Hugh Trenchard, had come into existence on June 6, 1918; it was tasked with the strategic bombing of German industrial centers, although, for a variety of reasons, many of the missions ended up targeting aerodromes and railroad transport.15 Merrill would have found fellow second Oxford detachment member Horace Palmer Wells already at No. 104; another member, William Ludwig Deetjen, had been killed in action on June 30, 1918, after just over three weeks with the squadron.

Merrill presumably spent his first three weeks at No. 104 becoming familiar with the squadron, the area, and the available planes. In any case, No. 104 is not recorded as having flown any missions between July 8 and July 31, apparently needing this time to recover from heavy losses in the preceding weeks.16

When No. 104 resumed flying on July 31, 1918, Merrill took part in that day’s mission.17 It was standard practice to conduct raids with twelve planes in two formations of six each (with two “spares” that, if not needed, would return once the lines were reached), and Merrill, with his observer, Southampton-born Leonard George Best, was in the first formation, led by Canadian Evans Alexander McKay. The two formations set out at 5:40 a.m.; their objective was the Usine Electric Works in Saarbrücken, some forty-five miles over the lines, which the planes of No. 104 crossed at Blâmont at 13,000 feet. Shortly before reaching Saarbrücken, they encountered a large number of enemy aircraft, most of which, however, were focussed on planes from No. 99 Squadron, which had taken off shortly before No. 104. The two formations from 104 reached Saarbrücken at 8:30 and dropped their bombs. The return journey to Azelot, largely uneventful, took less than an hour. That the journey out lasted more than two times as long as the return is explained in part by the need for the formation to climb to their planned altitude prior to crossing the lines. They thus had initially flown about thirty miles due east from Azelot to Blâmont before turning north towards Saarbrücken.

During August Merrill, with Best as his observer, took part in every mission flown by No. 104 Squadron, six in all—the relatively small number is partly explained by poor weather. Merrill and Best continued flying in the same formation led, in all but one instance, by McKay.

The planned objective when Merrill flew on August 1, 1918, was Karthaus, just south of Trier (Treves), thus considerably more distant than the previous day’s target; Karthaus was about eighty miles due north of Azelot and about sixty miles over the lines. The entire mission took just under three hours—shorter than the preceding day’s in part because the climb to altitude could be made in allied territory while flying north. Whereas the mission on July 31 had been without serious casualties, this second mission was not and was thus, unfortunately, more typical of raids flown by No. 104 Squadron. Engine trouble, all too frequent in DH.9s, prompted three planes to return early, and another plane lost its formation and had to land.18 The remaining planes approached Karthaus just before 8:00 a.m., but, as visibility was poor, McKay chose to target the railway station at Trier instead. Not far into the return journey, enemy planes attacked. Claims made by both sides are difficult to verify, but it is certain that one pilot from the second 104 formation was wounded, and one plane from the same formation was shot down and both crew members were killed.

After a period of poor weather, No. 104 Squadron resumed flying missions on August 11, 1918. On that day and the next the planned objective was the Benz Aviation Factory at Mannheim, 120 miles northwest of Azelot. On August 11, 1918, cloud cover prompted John Charles Quinnell, who was leading Merrill’s formation and the mission, to change course and target Karlsruhe. Meanwhile, both on approach and on the return, the formations were attacked, and one plane in Merrill’s formation was shot down and its crew taken prisoner. The two formations had taken off at 7:05 and returned to Azelot four hours later, with not very much to spare of the DH.9s’ four and a half hour endurance time. The next day McKay was back leading Merrill’s formation; the other formation’s leader and leader of the mission was Jeffrey Batters Home-Hay. Not long after crossing the lines, the planes of No. 104 were attacked, and Home-Hay determined to engage the enemy planes; a lengthy aerial combat ensued. It was probably during this engagement that Merrill helped bring down the enemy plane for which he shared credit that day.19 Home-Hay then led his formations to bomb an aerodrome at Hagenau, considerably short of Mannheim. It was not until the return journey that losses occurred: two planes in the same formation as Merrill were forced to land in enemy territory; their crews were taken prisoner. The remaining planes were able to return safely at Azelot.

By and large thus far, anti-aircraft fire had not been very effective against missions in which Merrill participated, but this changed the next day.20 The two formations from 104 took off in the middle of the afternoon on August 13, 1918, with McKay leading them; one plane with engine trouble returned to Azelot. Unfavorable winds made attacking the original target, a railway junction at Ehrang north of Trier, impracticable, and McKay chose to try instead to bomb railway workshops at Thionville, a little more than halfway to Trier. Anti-aircraft fire near Thionville hit one plane, whose pilot tried, unsuccessfully, to head back to allied territory. On the return flight, the remaining ten bombers of No. 104 Squadron were attacked by an equal number of enemy scouts, but it was apparently again anti-aircraft fire that accounted for 104 losing planes as they approached the lines. Ultimately two men, pilot and observer, from the flight led by McKay and in which Merrill was flying were determined to have been killed in action, while three men from the other formation were killed in action, one was wounded, and two died of their wounds.

Despite these heavy losses, the two formations from No. 104 Squadron flew again two days later on a combined mission with No. 99 Squadron in an effort to destroy German Gotha bombers at the aerodrome at Boulay.21 Merrill was again in McKay’s formation; Quinnell in the other formation was leading. Boulay was a considerably closer target than those previously attempted, and the mission was accomplished in under three hours. Enemy planes attacked as the planes of No. 104 were returning, forcing one plane to leave the formation, but ultimately all arrived back safely.

Such was not the case on 104’s and Merrill’s next mission on August 22, 1918, when they flew the considerable distance to Mannheim in order to bomb the Badische Anilin- und Sodafabrik works—thus returning to the strategic bombing for which the I.A.F. was intended. The formations headed initially to the southeast, to Raon-l’Etape to cross the lines, and very shortly after that they encountered a number of German scouts. Two of the DH.9s had to land and their crews were taken prisoner, but the remaining planes continued on course. Shortly before reaching Mannheim, where they successfully dropped their bombs, the two formations again encountered a large number of enemy planes and a fight ensued. Only five planes arrived back at Azelot four hours and twenty minutes after they had set off; one of the returning planes carried a dead observer.22 Merrill and Best’s DH.9 D7210 was the only plane in the second formation to return, all the other pilots (including Wells) and three of their observers were prisoners; one of the observers was dead; a total of three men from the other formation had been killed.

Given this level of loss, it is astonishing that formations from No. 104 Squadron were flying again a little more than a week later. Charles Louis Heater, a second Oxford detachment member who was at the I.A.F.’s No. 55 Squadron, later wrote that “Merrill took a main part in the reorganization of the squadron and showed a spirit that was of inestimable value in keeping the morale of the squadron at top notch, in spite of the losses.”23

On September 2, 3, and 4, 1918, Merrill, still with Best, flew the plane equipped to take photos on missions targeting enemy aerodromes.24 On September 2, 1918, bombs were dropped on Buhl aerodrome, and on the 3rd and 4th, the German aerodrome at Morhange was the target; there was but one casualty, an observer wounded by anti-aircraft fire.

On September 7, 1918, No. 104 flew another mission targetting the BASF works at Mannheim, but neither Merrill nor Best flew that day, when, once again, casualties were high. However, on 104’s next mission, on September 12, 1918, Merrill piloted the photo plane in the first formation. Best was due for leave and did not fly with him. Merrill’s observer was instead Percy Davey from Yorkshire, who had joined No. 104 only a few days previously.25 The object of this mission was to bomb railways near Metz, but engine trouble prompted several of the planes to return early, and cloud cover thwarted those who continued. Merrill was the first to land back at Azelot from this mission during which at least there were no casualties. Merrill was now also due leave, and this turned out to be his last flight with No. 104. After he returned from leave, he was withdrawn from the R.A.F. in order to serve with the American Air Service.

166th Aero Squadron

On October 4, 1918, Merrill, along with fellow second Oxford detachment member, Phillips Merrill Payson, reported to the U.S. 166th Aero Squadron stationed at Maulan, about forty-five miles due west of Azelot; detachment members Albert Elston Weaver, John Joseph Devery, Paul Vincent Carpenter, Harrison Barbour Irwin, and Perley Melbourne Stoughton were already there, and Fremont Cutler Foss would arrive a few days later.26 Merrill and Payson were the only ones who had had operational experience. Payson had been with No. 55 Squadron I.A.F. and was thus very familiar with the DH.4; Merrill would have to make the transition from 104’s DH.9s to the American DH-4s of the 166th.

The 166th had been assigned to the American 1st Day Bombardment Group on September 25, 1918, the day before the opening of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, to which the squadrons (11th, 20th, 96th, and 166th) of the Group were dedicated. It was not until October 18, 1918, however, that the 166th was ready to participate in missions.

Merrill did not fly in this first mission, and no missions were flown the next three days due to unfavorable weather. A mission was attempted on October 22, 1918, but was cut short by rain and clouds; Merrill, flying DH-4 32646 with Edward Crews Black (who had also been in the I.A.F.27) as his observer, was one of the fourteen pilots who made this attempt.28 The next afternoon Merrill flew the same plane, this time with observer George Deady Melican, in the second of two missions undertaken October 23, 1918, by squadrons of the 1st Day Bombardment Group. This second mission was a very large one, with planes from all four of the 1st Day Bombardment Group squadrons. Squadron commander Victor Parks, Jr., was to lead the planes of the 166th Aero, but crashed on take off, and Merrill took over as leader. Seven of the remaining twelve planes, led by Merrill, reached and bombed the objective, the Bois-de-Barricourt, from an altitude of 10,000 feet at 3:30 p.m. An encounter with enemy planes, during which two Fokkers went down out of control, prevented them from observing the results of their actions.29 All the planes from the 166th returned, although three, including Foss’s and Carpenter’s, were forced to land, fortunately in friendly territory.30

The 166th flew six more missions in October and four in November—whenever weather permitted; on three days they went out twice. On most of these missions, Merrill’s observer was once again Black, but during the two flights on November 3, 1918, his teammate was John Whitten McKeon; Black flew with him on the last two missions on November 4 and 5, 1918. On the 4th, as the 166th approached Montmédy, “the formation was attacked by eight Fokkers. After an especially vicious fight all our planes safely recrossed the lines. Three enemy aircraft were destroyed, one of which was a tri-plane.” 31 Merrill and Black were among those who shared the credit for one of these.32

It is remarkable that on all his flights, both with the 166th and previously with No. 104, Merrill reached the objectives and did not have to turn back or otherwise fail to complete a mission. DH.9s were especially prone to engine trouble, and the records of missions flown by the 166th show that the DH-4s had their share of problems—sometimes fewer than half of the planes of the 166th that set out reached the objective. Merrill was clearly a skilled pilot, but perhaps also fortunate in the planes he flew. He may also have had exceptionally good ground crews, and his own mechanical experience perhaps helped ensure that his planes ran well.

Not long after the armistice, the 166th Aero Squadron became part of the Army of Occupation in Germany. They were initially stationed at Joppécourt and then at Trier, a city Merrill had seen from the air on August 1, 1918, whilst with No. 104 Squadron.

Merrill was able to return to the U.S. towards the end of April 1919. He continued to fly, barnstorming, instructing, and taking up passengers. On August 25, 1921, while instructing a student near Winona Lake, Indiana, he fell from the plane the student was flying and was killed; the plane then crashed and the student also died.33

mrsmcq May 13, 2020

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Merrill’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Linn D Merrill. Merrill’s place of death is taken from Ancestry.com, Indiana, Death Certificates, 1899-2011, record for Linn D Merrill; his date of death is taken from “Two Killed in Airplane Fall.” The photo is a detail from a large photo of the 166th Aero’s B flight.

2 On Merrill’s descent, see documents available at Ancestry.com, as well as Merrill, A Merrill Memorial, and Dow, The Dearborns of Hampton, N.H. “Apparently” and “probably” because I am not certain of the reliability of some of the documentation.

3 See Merrill’s draft registration, cited above, and Adjutant General of the State of Maine, Annual Report for the Year Ending December 31, 1904, p. 48.

4 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Linn Daicy Merrill.

5 Ancestry.com, Cook County, Illinois, Marriages Index, 1871–1920, record for Linn D. Merrill, and other documents available at Ancestry.com. For his wife’s full name, see Ancestry.com, Denmark, Church Records, 1812-1918, record for Leonilda Barbara Manfroi.

6 See Merrill’s R.A.F. service record, cited above.

7 Reproduced on p. 187 of Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 4.

8 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

9 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

10 On 198 T.S., see Stedman, “Night Fighter Pilot,” pp. 37 and 46.

11 “Air Training in England Exciting.”

12 Cablegram 612-S; the confirming telegram is 852-R, dated March 1, 1918.

12a Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35,” locates Merrill at Amesbury when he was placed on active duty on March 23, 1918.

13 [Biddle?], “Special Orders No. 109”; this is dated June 5, 1918, but the correct date is almost certainly July 5, 1918. Heater, [Informal account], p. 124, indicates that Merrill went with a group, including Heater, from England to Azelot via Boulogne and Paris, with no mention of Issoudun.

14 Merrill’s casualty form (“Linn Daicy Merrill”) indicates he was posted to No. 104 on July 11; “American Fliers with the I.A.F.,” p. 133, indicates he was assigned on July 10, 1918.

15 On the I.A.F. and the discrepancies between its theoretical objective and actual practice, see Chapter 11 of Wise, Canadian Airmen and the First World War.

16 See Williams, Biplanes and Bombsights, p. 200.

17 I have not been able to consult original records related to No. 104 Squadron, but have relied on Rennles, Independent Force, for accounts of 104’s missions; he notes on pp. 10–11 the incomplete nature of the extant records.

18 On problems with the I.A.F.’s DH.9s and their engines, see Wise, Canadian Airmen and the First World War, pp. 294 and 303; Rennles, Independent Force, p. 7; and Mason, The British Bomber since 1914, p. 85.

19 See “Confirmed Victories U.S. Air Service Officers with Independent Air Force.”

20 I should note that in his account of this mission and the one on August 15, 1918, Rennles lists “2LT O.F. Merrill” as flying in McKay’s formation with observer Best; possibly this reflects an error in the original records.

21 Rennles, Independent Force, p. 90, initially indicates the target was “Aerodrome at Buhl,” but then writes “Boulay aerodrome.” Pattinson, History of 99 Squadron, p. 32, indicates the target was Boulay, and this accords with the flight path (over Nomeny) that Rennles describes.

22 Heater, [Informal account], p. 128, indicates that it was Merrill’s observer who was dead, but this was not the case; it was Percy Charles Saxby’s observer, William Moorhouse.

23 Heater, [Informal account], p. 129.

24 Heater, [Informal account], p. 129, indicates that Merrill was made a flight commander; this is not evident from the accounts of missions provided by Rennles, Independent Force.

25 See “Percy Davey.”

26 See “Roster of Commissioned Personnel of the 166th Aero Squadron.”

27 See “Lieut. Ed Crewe [sic] Black R. A. F., S. C. R. A. S”

28 Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron,” p. 91.

29 See Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron”, pp. 85 and 104, and Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 132–33. For the successful claim credits (Carpenter and his observer Richard Wilson Steele, and Alexander Tolchan with observer Herman Feinstein), see Victories and Casualties, p. 38.

30 Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron,” p. 85; I have not been able to identify the third plane forced to land.

31 Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron,” p. 86.

32 Victories and Casualties, p. 38. And see Thomas and O’Neal, “The 166th Aero Squadron,” p. 115.

33 “Two Killed in Airplane Fall.” Note: The date of death on Merrill’s death certificate (Ancestry.com, Indiana, Death Certificates, 1899-2011, record for Linn D Merrill) is August 26, 1921, and this date is repeated in a number of sources. However, newspaper accounts make it clear that the accident occurred on August 25, 1921, and that Merrill did not survive the fall.