(Columbus, Indiana, December 31, 1888 – Cincinnati, Ohio, February 21, 1966).1

Mooney’s great-grandfather, Edmund Mooney, was the founder of a tannery that became an important industry and employer in Columbus, Indiana; the firm was passed down in the family well into the twentieth century.2 Mooney’s mother, Laura Jean Mooney, née Henley, died in 1892; in 1900 both Mooney’s father—also Edmund Mooney—and his paternal grandfather died. Mooney and his sister and only sibling were cared for by aunts and uncles.3 The family continued to operate tanneries in Columbus and Louisville, Kentucky. Mooney, who generally went by “Will” rather than “Bill,” attended school in Louisville where one of his uncles, Thomas Mooney, lived; he graduated in 1907.4 I have found no record of his having attended college; instead he apparently became involved in the family business.5

In 1917 Mooney was at officers training camp at Fort Sheridan in Illinois for a time before transferring to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps.6 He attended ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University, graduating September 1, 1917.7 Along with most of his O.S.U. classmates, Mooney chose or was chosen to train in Italy, and he joined the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departed Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. The men of the detachment travelled first class and enjoyed shipboard leisure, including concerts featuring the violinist Albert Spalding, who was on his way to Italy. They also had Italian lessons, taught by Fiorello La Guardia. Once the convoy entered dangerous waters, the men took turns at submarine watch. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University.

A month later, on November 3, 1917, most of the detachment, including Mooney, left Oxford to go to Grantham in Lincolnshire where they would receive intensive training in machine guns at Harrowby Camp. Fifty of these men left Grantham on November 19, 1917, to begin flying instruction. Mooney, however, was among the men who remained at Grantham until December 3, 1917, when they were finally posted to squadrons.

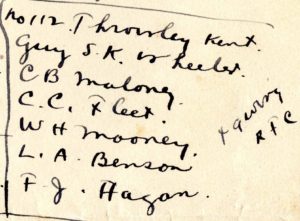

According to a list drawn up by Fremont Cutler Foss, Mooney was assigned to No. 112 Squadron, a home defense squadron at Throwley in Kent, along with Leslie Alfred Amzia Benson, Charles Carvel Fleet, Francis Joseph Hagan, Clarence Bernard Maloney, and Guy Samuel King Wheeler, all of whom had also attended ground school at O.S.U.8 No. 112 flew Camels, which, of course, could not be used for primary instruction. There must also have been some two seaters; Fleet wrote to Parr Hooper from Throwley that they were “billeted in nice homes and do not do anything except occasional flying when the pilots feel like taking them up.”9

Based on an ambiguous remark made by Clayton Knight—“Bill Mooney, a friend with whom I had trained since Stamford”10—it seems likely that Mooney’s next posting was to Stamford. His R.A.F. service record indicates that he was subsequently at Thetford in Norfolk, at No. 35 Training Depot Station.11 Assuming his training paralleled Knight’s, he would at Thetford have trained on DH.6s, R.E.8s, and, finally, DH.9s.12

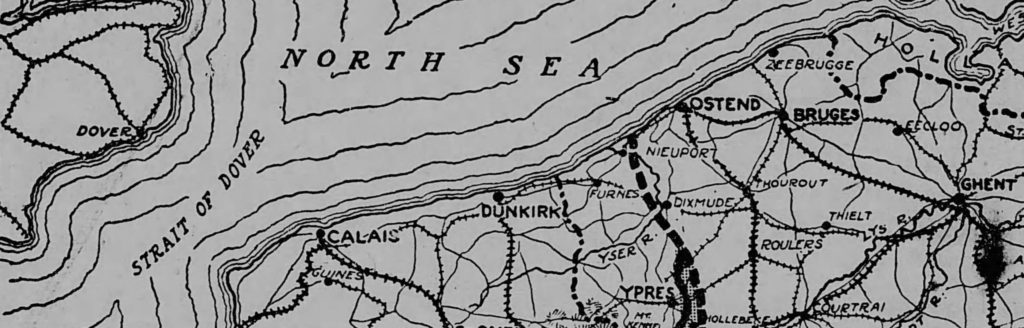

In early May 1918 Pershing forwarded the recommendation that Mooney and others be commissioned first lieutenants; the confirming cable is dated May 16, 1918, and Mooney was placed on active service on May 31, 1918.13 A little over three weeks later, on July 24, 1918, Mooney was posted to No. 2 Fighting School at Marske-by-the-Sea in Yorkshire.14 Finally, in mid-August, he was assigned to an operational squadron. Knight recounts how “When my time for posting overseas came, Bill Mooney . . . and I were sent down to London RAF Headquarters. Our orders read ‘Proceed directly to France’—but we wangled a two-day leave in London from a soft-hearted officer.”15 They went initially to a pilots pool near Boulogne. From there, on August 19, 1918, Knight was posted to No. 206 Squadron R.A.F. at Alquines, and Mooney to No. 211 Squadron R.A.F. operating out of Petite Synthe just south of Dunkirk on the French coast.16 Mooney was the only man from the second Oxford detachment to be assigned to this squadron, but he overlapped there with Allan Francis Bonnalie and Stuart Cary Welch of the first Oxford detachment.

No. 211 Squadron had previously flown DH.4s, but since March1918 had been assigned DH.9s.17 For much of 1918, apparently well into August, No. 211 had been part of the effort to impede German submarine operations by bombing the Zeebrugge mole and harbor and the docks at Ostend and Bruges.18

Less than two weeks after his arrival at No. 211, Mooney was taking part in missions over the lines.19 As was standard in R.A.F. squadrons, 211 was divided into three flights of six planes each. Mooney was assigned to the flight of which Bonnalie was acting flight commander; the other pilots were Welch and three Canadians.20 Bonnalie describes how, “On our first day over the lines with Moody . . . I had him on my right side flying next to me. I was leading the squadron that day and the raid was over Bruge [sic]. We started through the heavy anti-aircraft fire. . . .”21 Mooney, in a letter to his sister dated August 31, 1918, describes what happened then:

All of a sudden there was a crash and a bang and the old bus pitched up into the air and then settled a little. I knew that the burst had come pretty close and fully expected to break up and go spinning down, but when nothing happened I gingerly felt the controls and everything seemed all right. But when my observer tapped me on the shoulder and I turned around and took a look I nearly fell out of my seat. There was a great ragged hole in the fuselage just back of the observer’s seat, as big as a man and from where I sat it looked as if the tail was completely detached and was just following us along to be chummy. The ride home was absolutely the tensest situation I have ever been in. We were not at all sure that the tail wouldn’t drop off, but my observer was simply splendid. He would have a look around for huns, then take a look at the place we were hit, and the rest of the time he was hanging over my shoulder shouting in my ear, “I think it’s going to hold together. Fly carefully.” And then the humor of the situation would dawn on us and we would have a laugh. At any rate we got down at last and landed on our own drome, and I made the best landing I have ever made.22

Bonnalie remarks that “[Mooney] held his position with me, flew back and actually landed in formation.” The shell had blown “all the ammunition and the observer’s seat overboard, and [taken] off the fabric but doing no structural damage”—which perhaps accounts for there being no record of the incident in, for example, Sturtivant and Page’s listing of DH.9 aeroplane casualties.23 I have not been able to identify the stalwart observer, whom Bonnalie describes only as “an English gunner.”

I have also not found information about later missions flown by Mooney before his last one in DH.9 D565 on September 29, 1918, and the available information on No. 211 Squadron generally during this period is very sketchy.24 It was probably during Mooney’s time at 211 that the squadron’s focus shifted from submarine suppression on the coast to the bombing of inland aerodromes and supply and ammunition dumps; this would accord with the target on September 29, 1918, having been near Courtrai. Secondary sources indicate that, until September 28, 1918, bombers of No. 211 Squadron were escorted on their missions by fighter planes from other squadrons, but, perhaps because of the number of bombing raids at a time when fighters were so badly needed elsewhere, the planes from 211 Squadron that took off at 11:30 the morning of September 29, 1918, flew unprotected.25

The commanding officer of No. 211 Squadron, George Ranald MacFarlane Reid, fortuitously, provided an account of Mooney’s last flight that, except for his assumption that Mooney had perished, is presumably fairly accurate. The account is part of a letter that Reid wrote to Arnold Nugent Strode-Jackson, who had been in the same house at Malvern College and was now a brigadier general serving in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. Reid believed that Strode-Jackson had recently married Mooney’s sister; Dora Berryman Mooney Strode-Jackson was, in fact, Mooney’s cousin. The letter was evidently forwarded to Mooney’s family; it was printed on November 25, 1918, in a Columbus, Indiana, newspaper. The newspaper does not include a date for Reid’s letter, but it must have been written shortly after October 17, 1918, when the announcement of the Strode-Jackson–Mooney marriage appeared in the (London) Times. Reid wrote:

I am afraid that there is no possible chance that either Lieut. Mooney or his observer are alive today. On the 29th of September this squadron flew in a formation of twelve machines to bomb Ingelmunster railway station. As the machines turned back from the objective they were attacked by approx 50 E.A. [A] fierce running fight ensued in which every machine of our formation was heavily engaged. Two of our machines were shot down in flames, and several of the enemy. Lieut. Mooney was the pilot of one of the machines of our formation which was shot down in flames. His machine was last seen falling in flames near Iseghem and must have crashed to earth well behind the enemies’ lines. No further news has come to hand, . . . Lieut. Mooney had been attached to this squadron for nine weeks and had proved himself a really exceptionally fine and reliable pilot. His quiet but cheerful manner and his personality had made him a personal friend of every member of this squadron.26

One of Mooney’s uncles, William A. Mooney, had on November 9, 1918, already received news from the Red Cross that Mooney was “‘officially reported prisoner at Lazarett Bruederhaus Coblenz Stammlager Limburg Germany’.” The “information was a complete surprise to [William A. Mooney] as he had received no previous notice that Lieut. Mooney was missing.”27 Additionally, by the time Reid’s letter was printed, Mooney’s sister had received telegrams from Mooney himself, one including a request “that cigarettes and candy be sent him.”28 Nevertheless, in light of Reid’s communication, there was for some time understandably still “Doubt as to Fate of Lieut. Mooney.”29

An apparently completely separate set of circumstances also led, paraphrasing Mark Twain, to reports of Mooney’s death being greatly exaggerated. Mooney’s R.A.F. person casualty card has an annotation dated February 2, 1919, that reads: “When flying over enemy’s lines close to the coast Lt. Mooney’s machine was brought down & fell into the sea. He was drowned, but his body recovered & Buried in the British Cemetery at Cloukarque [sic; sc. Coudekerque?] outside Dunkirk.”30 A shortened version of this appears on his R.A.F. service record under the date March 16, 1919. I have not been able to trace the source of this misinformation.

Fortunately, on March 16, 1919, Mooney was actually being debriefed at an embarkation camp at Bordeaux, providing his own account of his last flight and its aftermath.

On Sept. 29th, I crossed the lines with my squadron to bomb the railroad station and sidings at Courtrai, Belgium. I had engine trouble on the way to the objective but did not consider it bad enough to return without bombing. I kept up fairly well until we bombed the target and were returning to the lines, but had fallen behind over the target and was a hundred yards or so in the rear trying to catch up when we were attacked by a German circus of sixty machines. There were thirteen of us. Six or seven or perhaps more of the Huns attacked me. My observer succeeded in keeping them off for a while, but eventually they shot him thru the head, then closed and shot me in the buttocks, the bullet entering near the spinal column. Somewhat dazed by the impact of the bullet, I got in a spin and fell spinning out of control for about ten thousand feet, the Huns following me down and firing all the while. The machine came out of the spin about four or five hundred feet from the ground, and side slipped steeply to the left but I caught it and was able to land without sideslipping or nose diving into the ground, merely pan caking on the left wheel and left wing tips, and turning over on my back. I think my observer fell into and became entangled in the controls when he was shot. German Infantry men rushed up and took us prisoner while I was still trying to get my observer from under the machine.31

Mooney’s observer, Victor Adolphus Fair of Dorset, had served in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps and been awarded the Military Cross for his actions during the German Offensive of March 1918. In August 1918 he had transferred to the R.A.F., serving initially with No. 49 Squadron. He had been injured on September 5, 1918, during a practice flight in which his pilot was killed. After being discharged from hospital, he joined No. 211 Squadron on September 27, 1918.32

Mooney knew that his observer was badly injured and had been taken to a field hospital, but did not know that he succumbed to his wounds that day: “I was unable to find out what became of him, but fear that he died of his would.”33 Fair was initially buried in the communal cemetery at Meulebeke, about two and a half miles northeast of Ingelmunster—the location, according to Reid, of the railway station targeted by the planes of No. 211 Squadron.34 Mooney’s “Courtrai,” about six miles south of Ingelmunster, is perhaps an approximation. Iseghem, where, according to Reid, D565 came down, is about two miles west of Ingelmunster.

To return to Mooney’s account: his own wound “though painful, was not serious.” After it was dressed, he was taken to Thielt and the next day, along with seven other captured aviators, set out by train for Germany. Conditions during the journey were poor and Mooney developed a fever; this led to his hospitalization in Coblenz. Not long after the American Third Army entered Coblenz in December 1918, Mooney reported to their headquarters and eventually made his way to Bordeaux. He closes his account of being shot down and captured by punctiliously noting the “Loss of Government property: One flying suit. One pair gloves. One pair goggles.”35

Just over a month after making his report Mooney was able to sail to the U.S. on the Siboney, which arrived at New York on April 27, 1919.36 He returned to Columbus and the family business, and later lived and worked in Indianapolis and Cincinnati in related businesses.37

mrsmcq July 10, 2020

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Mooney’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942, record for William Henley Mooney. His place and date of death are taken from “William Mooney is Dead at 77.” The photo is a detail from a group photo of Squadron 8 at the Ohio State University School of Military Aeronautics.

2 “Mooney Tannery Century of History is Outlined.”

3 Information on Mooney’s family and upbringing is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com and various newspaper articles from the period.

4 “Additional Personals.”

5 “Lieut. Mooney Captured by Germans,” “Word Received Lieut. Mooney was Captured.”

6 “Will Henley Mooney Starting for Italy.”

7 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

8 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

9 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 18, 1917.

10 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: Artist & Airman,” p. 206.

11 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for W Henley Mooney. Fleet, in a letter written May 31, 1918, to Benson, remarks that “Bill”—presumably Mooney—and Knight “have gone to 128 T.S. Thetford” (actually No. 28 Squadron; both No. 28 Squadron and No. 35 T.D.S. were at Thetford). The letter is in Benson, Leslie A. A. Benson Collection, 1917-1919.

12 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: Artist & Airman,” p. 206.

13 Cables 1047-S and 1331-R; McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

14 See Mooney’s R.A.F. service record, cited above.

15 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: Artist & Airman,” p. 206.

16 See “Lieut. C Knight USAS” and “Lieut. W H Mooney USAS.”

17 Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 435.

18 See “211 Squadron in World War I.”

19 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 117; and Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 35, state that R.A.F. regulations precluded new pilots flying over the lines until they had been at the front for two weeks, but it is clear from the histories of the second Oxford detachment men that the regulation, if it did, indeed exist, was not always followed.

20 Bonnalie and Lundberg, A Lifetime in Aviation, Chapter 7. Note: I had access only to an unpaginated and poorly produced ebook. Mooney’s name is consistently rendered “Moody,” possibly because Bonnalie misremembered the name, but possibly due to an error that arose when the ebook was created.

21 Ibid.

22 “Narrow Escape of Yank Airman.”

23 Bonnalie and Lundberg, A Lifetime in Aviation, Chapter 7; Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File (note: Sturtivant and Page follow the practice of some R.A.F. records and give Mooney’s last name as “Henley-Mooney”).

24 The 211 Squadron record book at the National Archives in London, which might include relevant information, is currently (July 2020) unavailable to me. The plane serial number is taken from the relevant entry in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II.

25 On the lack of escort, see Clark, et al., “211 Squadron in World War I”; “Victor Adolphus Fair. M.C.”; and “DH 9 losses on the 29th September 1918”; Clark had access to the relevant documents at the National Archives in London. See the relevant entry in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, for the take-off time.

26 “Small Chance Lieut. Mooney is Alive Now.”

27 “Word Received Lieut. Mooney was Captured.”

28 “Local Officer, Reported Dead, in Prison Camp.”

29 “Doubt as to Fate of Lieut. Mooney.”

30 “Mooney, W.H. (W. Henley).”

31 Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany (Mooney’s account is among the material appended after p. 327).

32 “Victor Adolphus Fair. M.C.”; “2nd Lieut.Victor Adolph Fair 7th Bn K. R. R. C.” provides dates of his R.A.F. service.

33 Presenting the Experiences, cited above.

34 See “Lieutenant Fair, V A.” for images of the relevant burial forms.

35 Presenting the Experiences, cited above.

36 War Department. Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Casual Officers on S. S. Siboney, departing Bordeaux April 18, 1919, arriving Hoboken April 27, 1919.

37 “William Mooney is Dead at 77.”