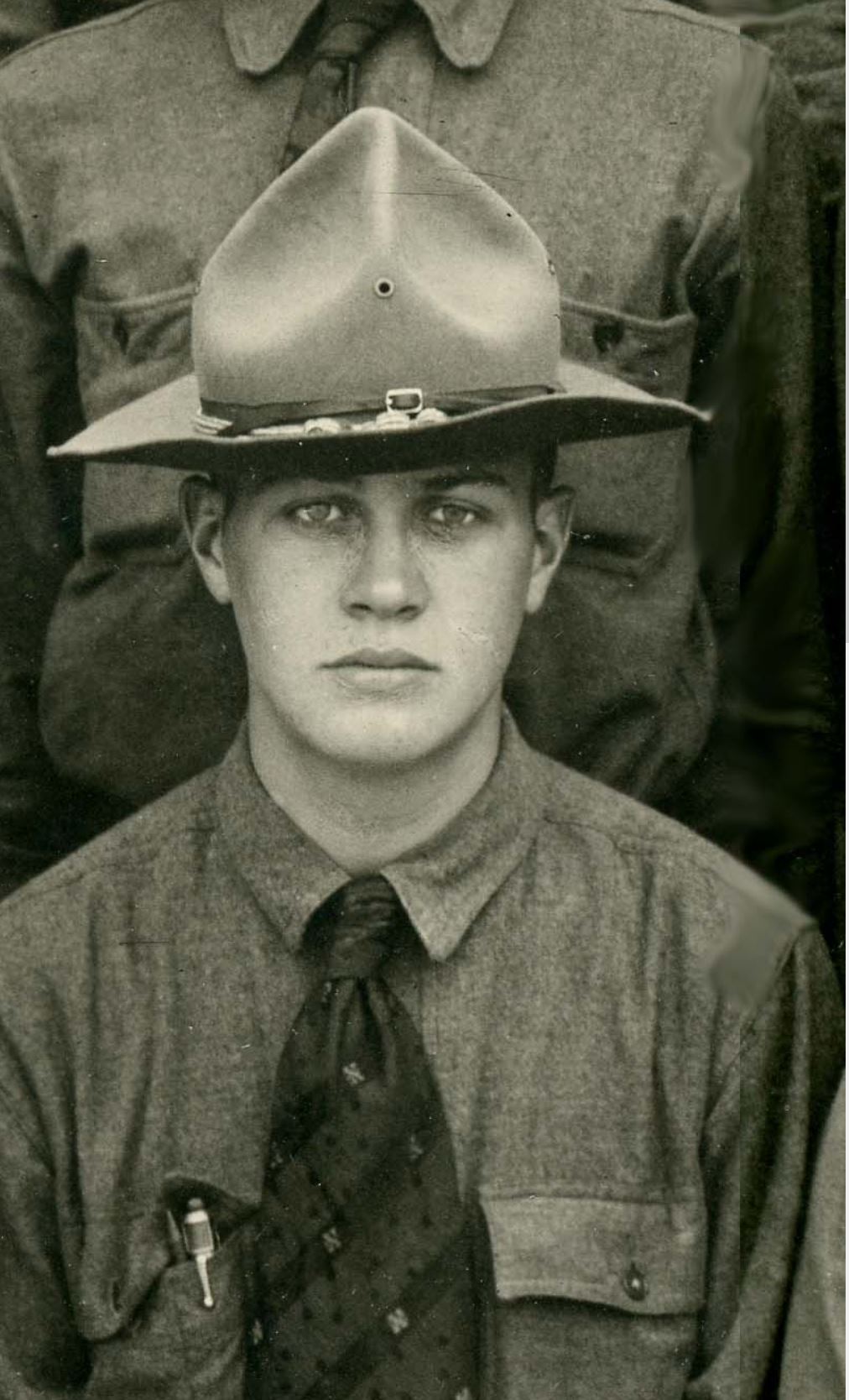

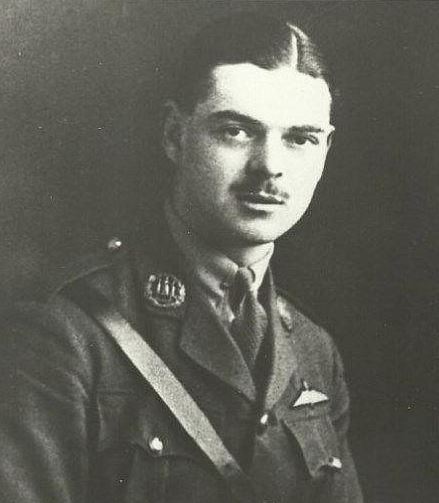

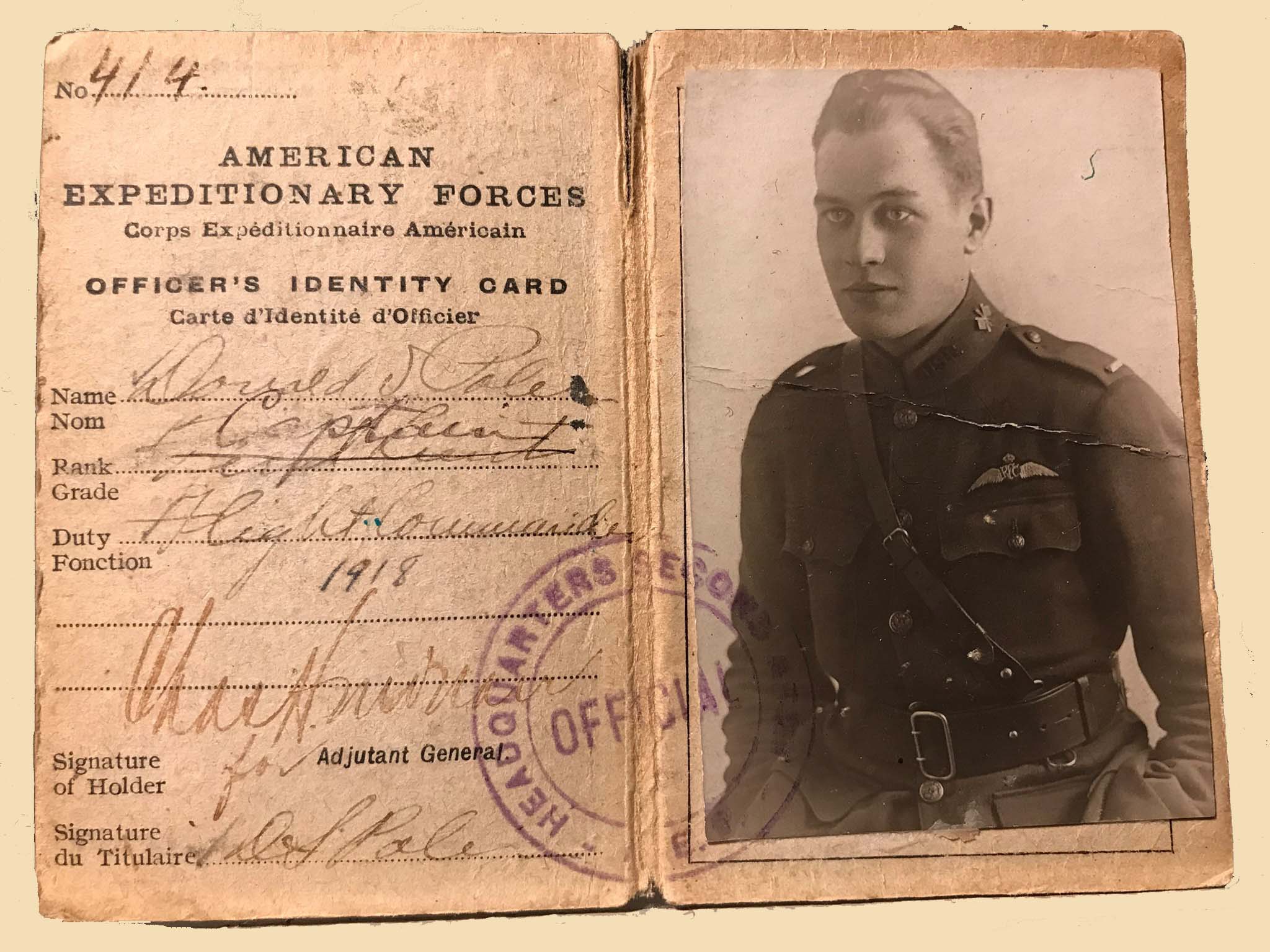

(Medina, New York, June 21, 1896 – Los Angeles, September 9, 1994).1

Oxford, Grantham ✯ Nos. 51 and 192 Squadrons ✯ Gosport ✯ No. 40 Squadron, Bruay ✯ No. 40 Squadron, Bryas ✯ 25th Aero Squadron

Poler’s paternal ancestors were settled in Saratoga County in eastern New York before they relocated in the 1830s to Shelby in Orleans County in the west of the state, where Poler’s great-grandfather and grandfather became prosperous farmers.2 Emmett Jay Poler, Poler’s father, worked for a time on the family farm but then became involved in manufacturing and was employed by the A. L. Swett Iron Company at Medina. In 1892 he married Lena Amanda Swett, youngest sister of company owner Albert Louis Swett. The Swett family can be traced back to the early days of the Massachusetts Colony; Lena Amanda Swett’s rather peripatetic father was born in Massachusetts but eventually settled in Medina.3

Donald Swett Poler attended high school in Medina, graduating in 1914.4 He enrolled at Syracuse University; the war interrupted his studies.5 When he registered for the draft he was in R.O.T.C. at the Madison Barracks at Sackets Harbor. He later recalled that “I transferred from the infantry, R.O.T.C., into aviation at the first chance I got.”6 Other men at Madison Barracks included Guy Maynard Baldwin, Wendell Ellison Borncamp, Lloyd Ludwig, and Donald Andrew Wilson. In early July 1917 Poler, along with those four went to Ithaca to attend ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at Cornell.7 They graduated on August 25, 1917.8

Along with three quarters of his classmates at Cornell, including Baldwin, Borncamp, Ludwig, and Wilson, Poler chose or was chosen to continue training in Italy. The men proceeded to Mineola on Long Island and, a little over three weeks after completing ground school, set sail from New York on the Carmania as part of a 150-man strong detachment bound for Europe. After a brief stop at Halifax, the Carmania joined a convoy and began the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. Poler said that “It took us fourteen days to get to Liverpool and I think we must have covered all the Atlantic, going back and forth. The trip was interesting since every day, for two to three hours, we were taught Italian by little Fiorello LaGuardia, who later became the mayor of New York City,” —LaGuardia was a diminutive five feet three inches to Poler’s nearly six feet—“and Albert Spaulding [sic], who was then a fine concert violinist. They both went on to Italy. For most of us, when we got to Liverpool, our orders were changed and we were much disappointed to learn that we were not going to sunny Italy.”9

In fact the entire “Italian detachment,” as they jokingly called themselves, was ordered to remain in England and to attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. The 150 men were divided into two groups, with ninety of them assigned rooms in Christ Church College in the charge of Elliott White Springs, and the remaining sixty, including Poler, in The Queen’s College under William Ludwig Deetjen. Having arrived too late for the start of the week’s classes, the men were free to settle in and explore Oxford and the surrounding countryside. Once their instruction began on October 8, 1917, because it was their second time going through much of the material, they did not have to put much effort into studying. According to Deetjen, on the second day of classes Poler joined him, Phillips Merrill Payson, Joseph Frederick Stillman, and Donald Elsworth Carlton for “quite a workout on the river today. Formed a 4 oared crew from our detachment and rowed on the Thames.”10

There was much socializing, and Americans were evidently in demand for Friday and Saturday night dances. Initially they were allowed late passes on these evenings, but this soon changed to late passes on Tuesdays and Sundays only. As Eugene Hoy Barksdale recounts it, “Well we were already dated up for the dance the following Sat. night [October 20, 1917] & when the time came & no passes could be gotten, my friend [Alexander Miguel] Roberts & I whispered to each other about slipping out & going any way.” Barksdale had second thoughts and “decided not to take the risk of being sent to France under disgrace,” but Roberts “collected up two other partners (Wilson & Poler) to venture out with him and they went out to see their fair dames.”11

Unfortunately this was the evening the men of the first Oxford detachment—fifty cadets who had arrived in early September— staged a bibulous celebration of their exam results and their impending departure from Oxford, thereby greatly annoying the British authorities. “The C.O. [Bertram Richard White Beor, C.O. of the Oxford S.M.A.] and Major [Gerald Graham] Adeley [assistant C.O.] had been strolling around & ran up on some fellows drunk. They ask [sic] to see their passes & the boys ran. The C.O. thot these were American boys . . . (The three boys were afterward found out to be English cadets).”12

Deetjen recounts in his diary how “At 11:30 [p.m.] we were all formed, and rolls were called. ‘A’ Flight was present, I had 3 men absent in ‘B’ Flight. They were Wilson (room mate) Poler and Roberts.”13 It seems the three men had assumed they would not be missed and, rather than returning late after the dance, had put up at the Clarendon Hotel. They returned to Queen’s around 10 a.m. Sunday “to find they were caught,” as they had been absent from the previous night’s roll call. “They were then told to report to the Lieut. Colonel (C.O.) the next day to be court martialed.”14

Deetjen did his best to lose track of the names of the men who had missed roll call, and Geoffrey Dwyer, who oversaw American cadets in England, did his best to defend Poler, Roberts, and Wilson to Adeley. Fortunately, when Deetjen took the three truants to Beor on Monday morning, the C.O. had calmed down. He “read them the riot act,” but did not otherwise punish them.15 However, as a consequence of the Saturday night shenanigans, all the second Oxford detachment were ordered to move from Christ Church and Queen’s to the (even) less comfortable Exeter College.

The men remained a month at Oxford. All of them hoped they would quickly move on to actual flying training, but openings at squadrons were in short supply. Thus most of them went on November 3, 1917, not to squadrons, but to a machine gun school, Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire. The preceding evening, in the midst of packing, Poler joined Fremont Cutler Foss, Perley Melbourne Stoughton, and Leo McCarthy in bidding a champagne and scotch farewell to Frank Aloysius Dixon, one of the select twenty going to Stamford rather than Grantham.16

Poler’s fellow detachment member Murton Llewellyn Campbell described the men’s activities once they arrived Grantham: “We are here . . . for four weeks, two on the Vickers and two on the Lewis. We are treated as officers and are called thus by the English officers. Eight of us in a tent with an orderly to take care of us. Nothing to do but go to the gun rooms and work on the Vickers all day long. We have from 9 to 1 P.M. with one or two hours out for field drill.”17 Campbell and his mates may have been housed in a tent, but it is more likely that he was actually referring to the wooden huts that housed most of the men at Grantham, including Poler. Poler’s hutmates were initially Borncamp, George Atherton Brader, Ralf Andrews Crookston, Burr Watkins Leyson, Clark Brockway Nichol, Hilary Baker Rex, and Wilson. Midway through November, places for fifty men opened up at squadrons, but Poler and his hutmates were not among the fortunate fifty. Some reshuffling was done, and a ninth man, Lloyd Ludwig, was added to their hut. Around this time they moved on from the Vickers to learning about and practice firing the Lewis machine gun.

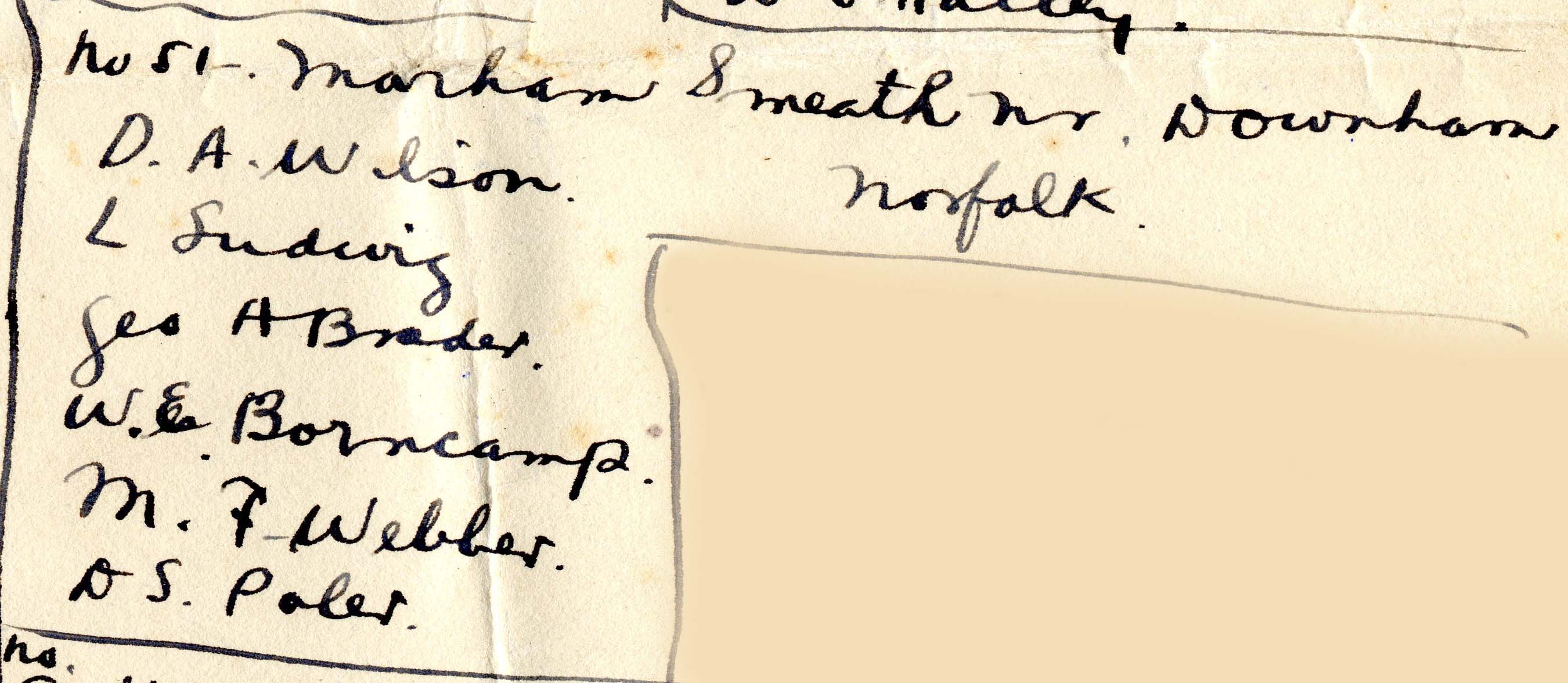

On November 29, 1917, the day after Thanksgiving, Ludwig wrote in his diary that he had gotten “news that we would be posted to Squadron on Monday. It looks as tho we’re going to a place called Marham Smeath, near Downham in Norfolk with Wilson, Poler, Brader, Borncamp & [Melville Folsom] Webber.” And, indeed, on December 3, 1917, the six men, who would continue as a group as they progressed through their training postings, left Grantham for No. 51 Squadron at Marham in Norfolk. No. 51, commanded at this time by Frederic Cecil Baker, was a home defense squadron tasked with defense against Zeppelin raids. Poler was billeted with Borncamp, Ludwig, and Webber at the local vicarage, the home of Harry Stanley Branscombe, vicar of Marham.18

The cadets were in for a disappointment. The day after their arrival at Marham they learned that “All the machines here are FE2B’s and as none of them are dual control machines; we will not be able to learn to fly here.”19 Ludwig writes of several rides as a passenger in the squadron’s F.E.2bs, and Poler later recalled that “I had my first flight there [Marham] in the front seat of an F.E. 2c pusher. We had quite a time flying up and down the Wash at night.”20 Poler’s first flight was probably actually in an F.E.2b, in which the observer sits in front, rather than in an F.E.2c, in which he would have sat behind the pilot.21 Otherwise, “We have absolutely nothing to do here except eat, sleep, enjoy ourselves and go on joy rides whenever we can. It is rather cold so we spend a good part of our time trying to keep warm.”22 On December 11, 1917, Poler went with Ludwig to nearby Narborough Aerodrome, where they had the opportunity to fly in a DH.6—a training aircraft that felt to Ludwig like “a steady slow bus” compared to the FE2b.23

Perhaps just to keep them busy, Major Baker arranged for the cadets “to go around and visit the two other detached flights which are stationed at Mattishall and Lydd [sic; sc. Tydd] St. Mary.”24 While Webber and Borncamp went to the latter air field, Poler and Ludwig spent a few days with A flight at Mattishall. “Once more we are billeted in the village. Have quite good rooms at the house of a Mr. & Mrs. Neave.”25

They got in no flying that day or the next. On December 15, 1917, “Tiny and Major Baker flew over from Marham for lunch. The Major said that we could go up and do some photography whenever the weather was good. However later in the afternoon, after they left we got a telephone message saying that we were all going down to Newmarket on Monday to be posted with the 192nd Squadron there.”26 In very inclement weather the next day they returned to Marham, and then on December 17, 1917, the six American cadets travelled via Ely to Newmarket, not far from Cambridge. No. 192, like No. 51, was a home defense squadron. Poler and Ludwig were assigned to A flight, commanded by a Captain Richardson. “The planes here are FE again, no dual controls, so we will have no chance of getting instruction.”27 And, between the fact that there were “practically no machines serviceable for flying”28 and the bad weather, flying was almost nonexistent at Newmarket.

Not long after Christmas, the luck of the six American cadets finally turned. On December 29, 1917 (Saturday), they learned that they were to report to “an office in London to get instruction to where we were to go. As we were to report Sunday morning Major Money suggested that we might like to run to town and spend the night there so we hustled around and left Newmarket on the 3:46 train reaching London about 6:20.”29 On the last day of 1917, Ludwig wrote in his diary: “Left the Waterloo Station at 9:35 for Gosport where we were to report. Arrived here about one o’clock. We are at what is known as the School of Special Flying, Fort Rowner, Gosport.”

Gosport was where Robert Raymond Smith-Barry had developed a training method for R.F.C. pilots that replaced seat-of-the-pants flying with theory and experience-based training, providing pupils with the knowledge and skills to, for example, get into and out of a spin. Smith-Barry had been able to take advantage of the two-seater Avro 504j, “a reliable aircraft with the handling characteristics of a single-seater fighter . . . [it] could thus be used to carry out all the aerobatics in his syllabus.”30 Poler recalled that “We were told that we were the luckiest in the crowd, as this primary training at Gosport was for instructors.”31

The School used Grange Aerodrome, an open area to the west of Gosport’s Forts Grange and Rowner; the students were quartered in the Fort Rowner barracks. Ludwig wrote that “Don Poler and I have a room together with an English officer. The rooms are fine—each of us has a spring bed, mattress, blankets & sheets, a washstand, a table and a wicker arm chair. It really is almost like luxury after what we have been having. The mess appears to be very good.”32

They began training almost immediately. On January 7, 1918, Ludwig wrote in his diary that “I did not get up with Lt. [Reginald John Bedlington] Benson at all today as he was busy with Don S.P. who after making some more landings with Benson in the afternoon went up for his first solo. He did mighty well and we all were proud of him.” Poler recalled that “Reading my diary recently I noticed that I soloed in five hours, twenty minutes. . . . The school was glad to get us off the ground and the faster we went on to advanced instruction the better.”33

In addition to their flying, the cadets still had machine gun and “buzzer” (Morse code) classes, but they also had a good deal of leisure time. There are many accounts in Ludwig’s diary of what “Don and I,” sometimes with George (Brader) or “Borny” (Borncamp), and occasionally Donald (Wilson), did in nearby Portsmouth: movies, theater, dinner, dances, and socializing with people met at Portsmouth hotels. On February 11, 1918, “the six of us Americans and 2nd Lt. Watson gave a dinner for our instructors at the Queens [Hotel in Southsea]. Capt. Smart, Capt. Watson, Lt. Benson, Lt. Long and Lt. Holbrow were there we had a fine dinner and fine time and went into the Hippodrome afterwards.”34 Three days later, they “Heard that we were going to leave here after this week.”35

On February 16, 1918, the recommendation for Poler’s and Ludwig’s commissions was forwarded by Pershing to Washington. The date of their graduation from this stage of R.F.C. training is not documented, but they probably, like Borncamp and Brader (whose R.A.F. service records include the notation “Grad C.F.S. 15-2-18”) finished up in mid-February.36

Around this time Poler asked “the Commanding Officer at Gosport to let me have one of his best Clerget Avros, just to go on a flight around the Isle of Wight. . . . I went around the isle but on the way back, where the west end of the isle meets the mainland at the ‘Needles,’ I didn’t recognize it as the point at which I should turn back. I continued west on the south coast of England and finally ran out of petrol. I didn’t know where I was and . . . made a forced landing on the parade ground of a tank camp. . . . In making my last turn in the Avro she slipped and fell.”37 There was some damage to the Avro and to Poler’s teeth, but the incident was apparently not serious enough to merit a casualty card.

Soon after this the six men were transferred to Castle Bromwich in Warwickshire; Poler recalled getting in “about eight or nine hours on S.E.5’s there.” Towards the end of the men’s second week at Castle Bromwich, on February 28, 1918, Poler, Wilson, and Ludwig practiced aerial fighting despite snowy conditions. After they landed, Ludwig went up again; while stunting, one of his wings collapsed, and he crashed and was killed.38

Over the course of March and the first part of April, Poler trained in Scotland; he was at Turnbery when he was assigned to active duty on March 20, 191838a (Brader was killed there in an air crash on April 5, 1918); from Turnberry he went to Ayr. “Gradually, after Ayr, we were assigned to a ferry pool in London. While we were in the pool we were sent to various places in England to ferry planes over to France. I ferried several S.E.5a’s over.”39

No. 40 Squadron, Bruay, April–May

Poler was posted to France in mid-April. On April 17, 1918, he crossed the Channel, this time not by plane but by boat, and then kicked up his heels at a pilots pool until April 24, 1918, when he was assigned to No. 40 squadron R.A.F.40 Reed Gresham Landis of the first Oxford detachment had been assigned to No. 40 two weeks previously; Robert Alexander Anderson of the second would arrive in July.

No. 40 Squadron was part of the 10th Wing of the R.A.F., which was attached to I Brigade, part of the British First Army. Stationed at Bruay and, since late 1917, flying S.E.5s and S.E.5a’s fitted with underwing bomb racks, No. 40 had assisted the British Third Army during the initial phase of the German Spring Offensive from March 21 through April 5, 1918.41 No. 40 then returned to the First Army front and was intensely active during the Battle of the Lys, which was winding down when Poler arrived. Prior to Lys, the front line had been just east of Armentières, but that city had fallen, and the front was now approximately ten miles west of it. The part of the front assigned to the First Army had run from just north of Armentières south to Gavrelle near Arras; it now stretched approximately from the Forest of Nieppe (due west of Armentières) south to Gavrelle.

In the face of the German advances in March and April, a number of R.A.F. squadrons relocated west to safer regions, but No. 40 was not among them. On April 14, 1918, Gwilym Hugh Lewis, leader of No. 40 Squadron’s B flight, wrote to his family from Bruay that “We haven’t moved our aerodrome yet, though the Huns have advanced north-west of it. We are not anxious to do so, as we never get bombed here.”42 On the day Poler arrived at No. 40 Squadron, however: “We have now got a new form of amusement. We spend most of our nights trembling in every nerve while high velocity shells pitch within a few hundred yards of us. Most of them pitch in a little valley just the other end of the aerodrome, but at other times they drop them around the town. They make an enormous noise and cause great damage.”43

Poler, consulting his diary, recalled in the early 1960s that “Between assignment [to No. 40 Squadron] and my first patrol the time was well spent in familiarizing myself with the equipment, gunnery practice, Cook’s Tours along the front lines, and in getting generally acquainted with the terrain.”44 Poler had his first “Cook’s Tour” on April 28, 1918, when Lewis took him and another recent arrival, Frans Helfrich Knobel, on a line patrol.45 The squadron record book does not note their route that first day, only that no E.A. (enemy aircraft) were sighted. Poler got in a second line patrol on May 2, 1918, led this time by Cecil Oswald Rusden (Lewis being on leave). They flew at low altitude in poor visibility from La Bassée, just east of and over the lines from Bruay, south to Arras. Two days later, Poler flew his third and final introductory line patrol in the company of Knobel and another newcomer, William Leslie Andrew, and three experienced pilots. This time the route took in the length of the First Army’s sector, from the Scarpe (Arras) north to Armentières, and the patrol lasted about an hour and a half.

On May 6, 1918, slightly less than two weeks after his arrival at Bruay, Poler, flying the absent Lewis’s S.E.5a D3540, participated in the first of the more than ninety offensive patrols that he flew with No. 40 Squadron over the next four months.46 He was one of eight pilots who took off at 6:20 that evening on a mission that lasted about an hour and a half. Cecil William Usher, apparently flight leader in Lewis’s absence, reported seeing three triplanes 6,000 feet below; he, Poler, Stanley Porteous Kerr, Henry Samson Wolff, and Henry Harben Wood dived on them in formation, but, as Usher reported: “Triplanes disappeared in mist near Bois de [sic; sc. du] Biez,” i.e., about two and a half miles north-northwest of La Bassée.

Over the next week Poler, usually flying S.E.5a D3540, participated almost daily in offensive patrols, and on some days took part in two missions. He later recalled that “Patrols at dawn, or afternoon or evening, were made usually with one or two flights of 5–7 planes each, and were started at 18,000 feet. Patrol time was determined by our gas supply, 2 hours and 15 mins. And it took about 45 minutes to reach patrol altitude.”47 The front was relatively quiet; nevertheless some of Poler’s fellow pilots engaged in combats and reported sightings during their patrols in the first three weeks of May. Poler’s most frequent entry in the squadron record book’s remarks column was “No E.A. seen”—he was evidently still learning to see in the air. May 14 and 15, 1918, brought a new task: Poler was among those assigned to escort pilots attacking enemy balloons.

On the latter day, Poler flew a second mission late in the afternoon and for the first time was involved in attacking an enemy plane. The patrol, judging from their reports of sightings of enemy planes, began near the north end of their sector around Estaires and flew south towards Arras where they espied “2 E.A., (one Phalz [sic] and 1 Albatross) in company near Scarpe and W. of S.E. patrol.” Usher shot down the Albatros and received credit for it. Then, with John Leam Middleton, George Watson, and Poler, he focused on the Pfalz, later reporting that the “Pilot of Phalz, which was new type, with Albatross Scout tail, was exceedingly good. . . . This machine was attacked by 3 other S.E.s of the patrol and forced right down to 200′ where he contour chased across to La Brayelle. S.E.s finished at 2,000′ & returned heavily archied.” (La Brayelle airfield was just west of Douai.) Poler reported that he “With other S.E. drove down Phalz Scout near Brebières.”

The archie encountered on the 15th did not put S.E.5a D3540 out of commission, for Poler flew it the next afternoon when, if I have correctly understood the squadron’s record book, the patrol, led by Usher, flew from Douai north to Vieux-Berquin; they saw eleven enemy aircraft east of Armentières but were “unable to attack owing to shortage of petrol, having been up nearly 2 hours.”

The next day, May 17, 1918, Poler flew a patrol with Lewis, who had just returned from leave and was once again leading B flight. Lewis resumed flying D3540; Poler flew several different S.E.5a’s over the next week or so, eventually settling on D3941.

On May 20, 1918. Poler was involved in his first “dog fight”; the others in the flight during this patrol were Lewis, squadron C.O. Roderic Stanley Dallas, Rusden, Ivan Frank Hind, and Wood.48 They left the ground just before 7 p.m. and, an hour later, over Merville, encountered a number of enemy planes. According to the joint combat report they filed, “The S.E. patrol attacked an E.A. formation and a general fight ensued, all pilots engaging various E.A. During the combat two pilots saw one E.A. low down and falling out of control, but no pilot is prepared to claim the credit of shooting it down.”49

The next morning Lewis’s flight, including Poler flying S.E.5a D3561, again engaged a large number of enemy aircraft, this time over Douai. Lewis described the encounter: “Led patrol into action with 12 E.A who were below SEs. E.A. were at once reinforced by the arrival of a further 8 E.A. A dog fight ensued between the whole of the two formations.” The planes of No. 40 Squadron were flying at around 18,000 feet when they dove on the enemy aircraft beneath them. In the remarks column of the squadron record book Poler noted of his own participation “2 indecisive combats.” He later recalled that “I got in several shots at a Pfalz, and had a stoppage in my Vickers, and used the Lewis gun on an Albatros. After a few minutes the Huns cleared out and we went back to count our bullet holes. One [D5968] had so many that the ship was written off.”50 Lewis received credit for one plane destroyed, and two other flight members recorded a plane driven down out of control.51 On returning from another offensive patrol late that afternoon when no enemy aircraft were seen, Poler had the misfortune to stall D3561, which pancaked and overturned; the plane was struck off charge; Poler was not injured.52 He flew D3530 on uneventful morning patrols the next two days, and then “Capt. Lewis gave me a new machine and I took it up for a test to 21,000 feet. It was perfect. Cold up there without oxygen, and tiresome. We have been carrying 20 pound Cooper bombs just for morale, but with no bombsights we can do little damage.”53 The new plane was presumably S.E.5a D3941, which, according to the record book, Poler took for a ninety minute test flight the morning of May 25, 1918, and which he continued to fly through June 7, 1918.

The end of May 1918 would bring a kind of mission new to Poler. From May 29 through June 2, 1918, he took part in six bombing missions, with Estaires and Merville as the main targets. The squadron record book notes some ground strafing, which suggests that these patrols were flown at low altitude where the lack of bomb sights was perhaps not an issue.

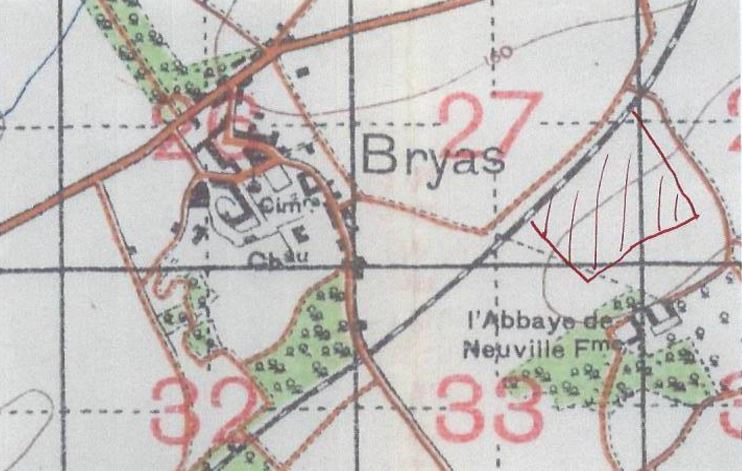

No. 40 Squadron, Bryas, June–September

On June 4, 1918, No. 40 Squadron finally put a bit more distance between themselves and the front, moving about eight miles southwest to Bryas (now Brias) “near St. Pol, on a beautiful but small aerodrome at the edge of a woods. On days when the weather was too ‘dud’ to fly we would visit the front lines near Arras, or go to the beach at Paris Plage, or ride the saddle horses assigned to the squadron.”54 No. 40’s missions and targets, however, did not change with their location: they continued to conduct offensive patrols and bombing missions along the First Army front. On June 7, 1918, three days after flying D3941 to the new aerodrome, Poler took part in an offensive patrol over Estaires and engaged an enemy two seater. His S.E.5a, D3941, was “shot through by m[achine] g[un] fire” and badly enough damaged that it was struck off charge; Poler was not hurt.55

The next day, June 8, 1918, Poler experienced his second crash while with No. 40 Squadron. Flying S.E.5a D3505 for the first time, he left Bryas with Lewis and Usher shortly before 10 a.m. on a line patrol. On their return, Poler “Lost wheel and tilted on nose”; the plane was struck off charge a few days later; Poler was OK.56

The day after this incident, the Germans initiated the third phase of their Spring Offensive, the Battle of Matz. As a result, according to Lewis, “Life has been extremely dull lately. The attack down south has robbed us all of the chances of doing what we are, I suppose put here to do.”57 Poler’s repeated report “No. E.A. seen” no longer had anything to do with his sky vision but rather with the absence of enemy planes. Lewis wrote “Time after time, day after day, I have patrolled the whole sky at all heights in all places, and found nothing . . . .”58

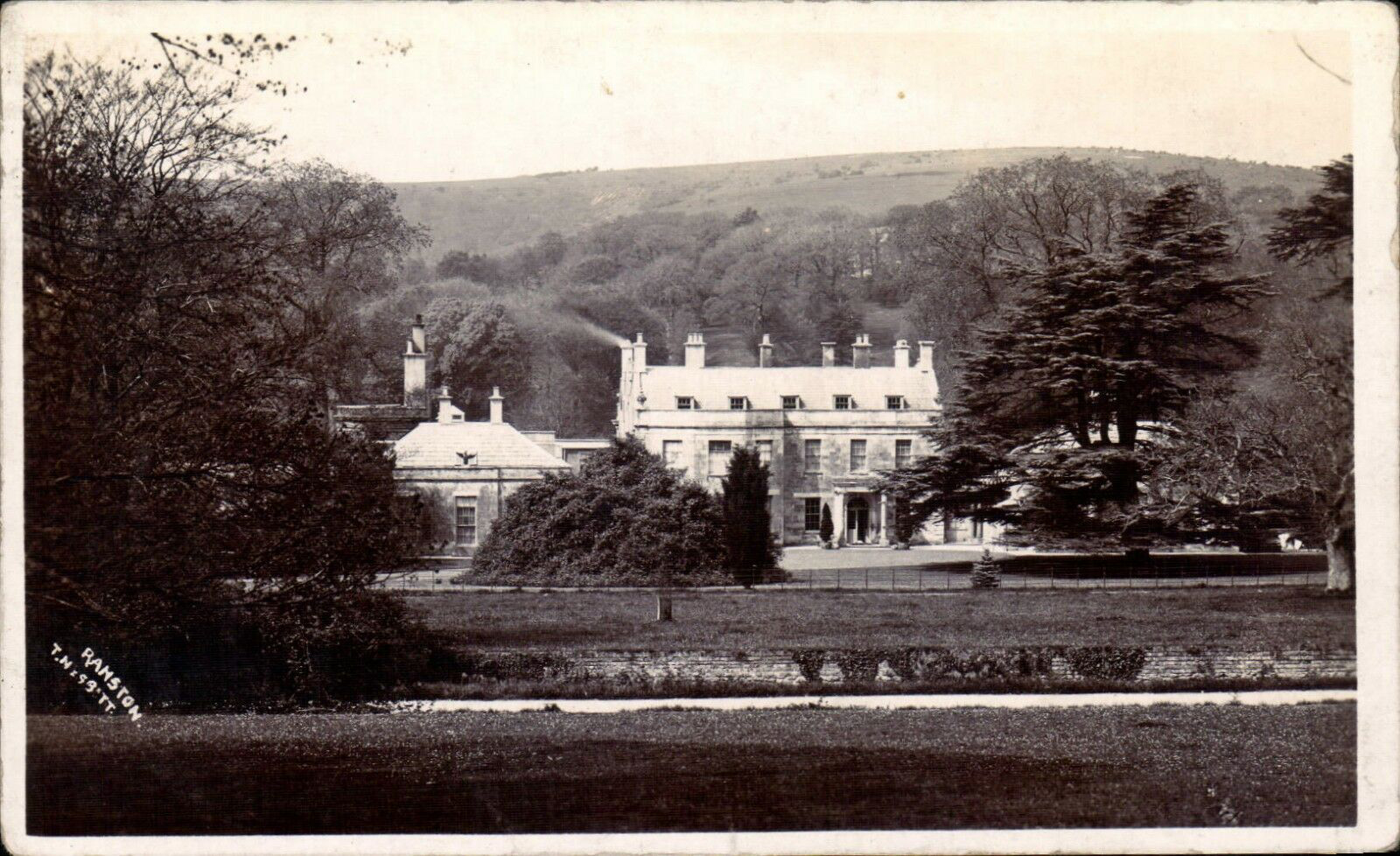

Poler took part in two more offensive patrols in early July 1918 before going on leave from July 6 until July 25, 1918. On his first evening back in England, he dined at the Putney home of American businessman Robert Noyes Fairbanks, where he ran into Harold Ernst Goettler.68 Lewis had written his family that Poler “is home on leave. I told him to call if he felt like it.”69 There is no record of a visit, but it seems likely that Poler, like Keith Logan (Grid) Caldwell and Edward Corringham (Mick) Mannock, would have availed himself of Lewis’s invitation to visit the family home, St. David’s, on Templewood Avenue near Hampstead Heath.70 While in England Poler “had some clothes made, and got some teeth fixed, the ones knocked loose in a crash in training at Gosport. And was a weekend guest at the home of Sir Randolph Baker, M.P., in Dorsetshire.”71

Poler took part in two more offensive patrols in early July 1918 before going on leave from July 6 until July 25, 1918. On his first evening back in England, he dined at the Putney home of American businessman Robert Noyes Fairbanks, where he ran into Harold Ernst Goettler.68 Lewis had written his family that Poler “is home on leave. I told him to call if he felt like it.”69 There is no record of a visit, but it seems likely that Poler, like Keith Logan (Grid) Caldwell and Edward Corringham (Mick) Mannock, would have availed himself of Lewis’s invitation to visit the family home, St. David’s, on Templewood Avenue near Hampstead Heath.70 While in England Poler “had some clothes made, and got some teeth fixed, the ones knocked loose in a crash in training at Gosport. And was a weekend guest at the home of Sir Randolph Baker, M.P., in Dorsetshire.”71

By the time Poler returned to No. 40 Squadron, Lewis himself had gone on leave, knowing that he would not be returning to France. From a passing remark in David Gunby’s history of the squadron, it appears that Hind took over as B flight leader.72

On the last day of July 1918 Poler made a visit to No. 56 Squadron, stationed at Valheureux, perhaps to visit Borncamp, who had been with 56 for about two weeks. Otherwise, in late July and early August 1918, Poler continued flying offensive patrols, more often than not involving the bombing of targets east of Arras. On one occasion (the page in the squadron record book lacks a date), Poler fired on two enemy balloons; Landis, on the same patrol, reported that “the balloons were pulled down in a very damaged and semi deflated condition.”

On August 7, 1918, flying E1284—his plane since late June—Poler crash landed at Ostreville shortly after taking off from Bryas on an offensive patrol; the engine had failed. Yet again the plane was so badly damaged that it was struck off charge while Poler walked away uninjured.

The next day, August 8, 1918, marked the opening of the Amiens Offensive, the British and French attack along a fifteen-mile front east of Amiens and the beginning of the Hundred Days Offensive. On that day and on the morning of the ninth it was business as usual for No. 40 Squadron. Poler was involved in indecisive combats east of Arras on both the morning and afternoon patrols on August 8, 1918; both that afternoon and the next morning he experienced engine trouble in S.E.5a E1304.73

Beginning the afternoon of August 8, 1918, strenuous efforts were made by the R.A.F. to bomb bridges over the Somme east of Amiens in the hope of trapping German troops on the river’s south and west banks near Peronne. The next afternoon the fighter squadrons of I Brigade, including No. 40 Squadron, were “brought down from the north” to patrol “just above the clouds,” thus freeing up the fighter squadrons of IX Brigade to escort the bombers tasked with destroying bridges.74 Poler did not take part in that afternoon’s mission, described in the record book as “escort to bombers,” as he needed to test a new plane, C9132. He did, however, fly this S.E.5 with the squadron the next morning, August 10, 1918, when thirteen planes took off at 6:30 a.m. and landed about two hours later at Moyencourt, having, according to Poler, gotten lost; they then flew to Bertangles, where No. 84 Squadron R.A.F. was stationed, and “had breakfast, filled up the tanks.”75 They were back at Bryas at 11:20, having been in the air nearly three hours in all. A second patrol in the afternoon, described cryptically in the record book as “O.P. and Fienvillers,” involved another three hours and forty minutes in the air. Poler’s diary provides more detail: “At 2:00 PM went down to the ‘push’ east of Amiens, and did a line patrol. Had tea at 43 Sqdn. [at Fienvillers]. At 5:00 went on another show then came home” arriving back at about 7 p.m. having flown over country just abandoned by the Germans and having experienced “the longest day of flying—6 hours.”76 Enemy aircraft were seen by some of the pilots, but not engaged.

On August 11, 1918, No. 40 Squadron made two offensive patrols in the afternoon; Poler returned early from the first one with engine trouble, but flew C9132 again later in the day. At least the latter mission was flown back up north, as Poler reported seeing “1 E.A. twoseater E of Béthune at 3000′ too far E to engage.”77

On the morning of August 12, 1918, the squadron flew south to Allonville, just northwest of Amiens.78 Soon after their arrival they set out on an offensive patrol—presumably still tasked with patrolling at altitude to protect the bridge bombers and their escorts. This time enemy aircraft were encountered in abundance: the reports in the record book mention “8 Fokkers,” “6 E.A.,” “20 E.A. over Peronne,” “About 50 E.A. seen,” and “Innumerable E.A. seen.” Poler, who flew C9132 on that patrol, later recalled that “We tried to gain height on a formation of twenty-two (22) Huns, but could’nt. [sic] At last the Huns broke up and we went after them. Later six (6) of us climbed up to 15,000 feet and attacked six (6) E.A. twelve miles over the lines, and just over the village of Brie. We fought for a full half-hour and had eight indecisive combats, one of which I claimed as out of control.”79 During this mission Hind was shot down and killed, and Wood shot down and taken prisoner.80 Poler recalls flying a second offensive patrol in the afternoon: “I got up to 8000′ and my engine made an awful roar and then stopped. I got back all right with two big slide-slips [sic]. Found that the front of engine casing was cracked.”81

No. 40 Squadron apparently flew its last two missions in support of the Amiens Offensive on August 14, 1918. They made the fifteen minute flight from Bryas to Fienvillers, about fifteen miles north of Amiens, in the early morning and immediately set out on an offensive patrol. Poler, however, flying D6180, twice had to return to Bryas because of oil leakage and did not participate in the morning patrol. He arrived in time for the second mission of that day, which was uneventful except insofar as more than half the planes (not including Poler’s) had to return early because of engine or gear trouble.82 In the early evening the squadron returned to Bryas and the next day resumed their patrols on the First Army’s sector.

On August 16, 1918, a day after an indecisive combat as well as bouts of radiator and engine trouble in C9132, Poler took off early in the morning in D8440 with two other pilots, evidently balloon hunting. While Wolstan Vyvyan Trubshawe “fired 250 rds at enemy balloon without result,” Poler reported having “Shot balloon down in flames”; his combat report indicates this occurred near Biache-Saint-Vaast, very near where he scored his previous balloon.83

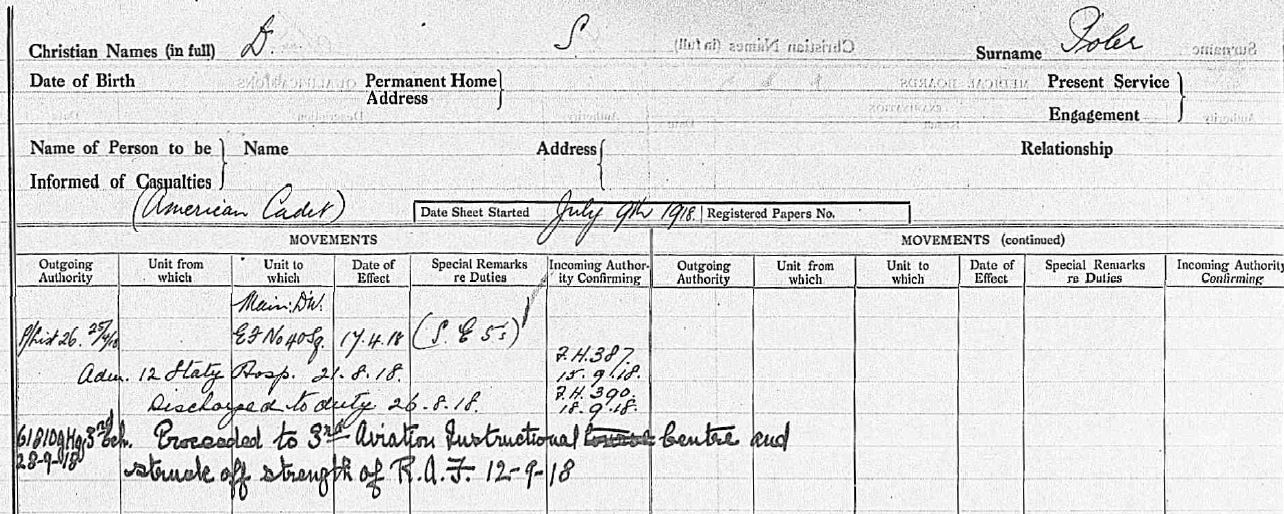

Poler took part in several largely uneventful offensive and line patrols through August 21, 1918, and then came down with tonsillitis, for which he was treated at No. 12 Stationary Hospital at St. Pol. He was “discharged to duty” on August 26, 1918.84 Prior to his sick leave, enemy aircraft were rarely sighted during patrols by No. 40 Squadron planes, but on August 27, 1918, the record book noted “abnormal activity of E.A.,” and this would be the case during the remainder of Poler’s time with No. 40. On August 26, 1918, the First Army had opened the Battle of the Scarpe, “striking eastwards from Arras,” and No. 40 Squadron was tasked with making patrols starting at dawn to “prevent useful observation from enemy balloons in the battle area, to keep enemy airplanes at a distance, and to afford general protection to the low-flying planes.”85

This assignment led to a memorable encounter for Poler on August 27, 1918, that he recalled in his 1959 interview with James J. Sloan and George D. Hocutt: “Toward September . . . three of us took a dawn patrol.”86 According to the record book, there were initially four pilots, Middleton, Poler, Philip Bryce Myers, and Arthur Thomas Drinkwater, but Drinkwater returned after fifteen minutes with engine trouble. Middleton wrote of that patrol that “We were to fly at 6,000 feet and look after 208 Squadron who were to shoot down balloons south of Arras. We got to the lines at about 6am. . . . There seemed to be no Camels [of 208 Squadron] in sight and there was a balloon somewhere near Vitry that seemed to be bearing a charmed live; nobody seemed to be taking the slightest notice of it. We waited about for quite a long time but still no Camels turned up.”87 Poler recollected that a “balloon was up around Cambrai. There was another balloon south of there. . . . I signaled to Middleton that I would go after one balloon. He signaled that he would go after the other.”88 As they approached their respective targets, both were attacked by Fokkers. Poler: “Just before I opened fire I noticed fourteen (14) Fokkers driving [sic] at us from the West. Eight (8) of them piled onto me, then at three thousand feet. I threw my machine around until all but one left and I was down to 1,000 feet over a gas attack and three miles over and completely dazed as to direction. In order to save myself, I had to roll six times before he left me. During the fight one bullet ripped open my sleeve; and my watch, on the instrument board, saved a bullet from entering my petrol tank.”89 Poler landed back at Bryas at 7:55 a.m., as did Myers. Middleton had a worse time: “Just when I was getting within range I saw five Fokkers coming down on me. I was only at about 5,000 feet at the time so I was soon in a mess. They started firing at me right away but I seemed to be dodging the bullets alright. But not for long! With a crack and a bang my engine ceased to function!! I was still about three miles from the lines, so I could not hope to reach them. The chaps in my flight saw what had happened and they drove the Huns away so that I was able to land in peace.”90 Poler recalled that Middleton “got back to the squadron in about three days. He had crashed in no-man’s land and he hid in a shell hole there.”91 The squadron record book specifies the location: “W of Mercatel.”

It must have taken some nerve to fly two more missions that same day. And Poler would in the meantime have learned that his fellow second Oxford detachment member Anderson, whom he had known since ground school at Cornell, had failed to return from the three man “dawn patrol” that had set out just before Poler’s. Nevertheless Poler took off a second time late in the morning of August 27, 1918, this time flying E4036—C9132 was perhaps undergoing repairs. He had to return just over an hour later with engine trouble. In the afternoon he was back flying C9132, but again had to return because of engine trouble.

Bad weather on August 28, 1918, meant there was little flying, but on August 29, 1918, ten planes from No. 40 Squadron, including C9132 piloted by Poler, set off at 6:15 a.m. A number of enemy planes were observed. Poler, as was his wont, focussed on an enemy balloon and was able to report having driven it down. Later in the morning Middleton flew C9132 and drove a Fokker down out of control but stood the plane on its nose when he landed. Middleton was OK, but C9132 was struck off charge three days later.92 Thus Poler was flying yet a different plane, D8440, when he took part in his second mission that day, when many enemy aircraft were seen near Cambrai, too far east to engage. Over the course of the last two days of August Poler flew five missions and engaged in “indecisive combat” during two of them. In the evening on August 31, 1918, with Trubshawe acting as his guard, Poler set out in S.E.5a E3982 on a “Special Mission.” He reported that he “Dived on hostile balloon SW of Douai but was unable to attack owing to heavy machine gun barrage. Saw the observer jump out.”

During the first week of September Poler flew ten missions. On September 6, 1918, flying E9135 he experienced engine trouble and had a forced landing at No. 6 Squadron, stationed at Le Hameau, north-northwest of Arras, but both he and the plane were OK. Leaving the machine at Le Hameau, Poler returned to Bryas and the next day flew S.E.5a E4053 on his final mission with No. 40 Squadron. At 6 a.m. he, Gilbert John Strange, and Burwell “went over especially for balloons.”93 The remarks column in the record book states that he “Fired 50rds at hostile balloon S of Cambrai saw 1 observer jump out. 7 Fokker biplanes seen. 1 indec: combat.”

Bad weather kept No. 40 Squadron on the ground for the next week, during which Poler learned that he was about to be transferred back to the American army. On September 12, 1918, he, along with Burwell and Landis, “Proceeded to 3rd Aviation Instrn. Centre & Struck off Strength of R.A.F.”94 According to Paul Stuart Winslow of the first Oxford detachment, Poler, Burwell, and Landis were part of a group of thirteen American pilots serving with the R.A.F. ordered at this time to the 3rd A.I.C. at Issoudun. They “reported to Headquarters and were told to come back tomorrow. . . . When we reported to Major [Thomas George] Lamphier [sic; sc. Lanphier], we were told that we were ordered here by mistake, and they did not know what to do with us, but would wire Tours and let us know tomorrow.”95 After much confusion Poler, Burwell, and Landis were assigned to the U.S. 25th Aero Squadron at Colombey-les-Belles; Baldwin and Wilson as well as several other second Oxford detachment members would also join the 25th Aero. Landis was made C.O. of the squadron and Poler was B flight commander.96

On October 24, 1918, the squadron moved to Toul, where it joined the 17th, 148th and 141st Aero Squadrons to form the Fourth Pursuit Group of the American Second Army at Gengoult Field.97 Poler recalled how “Every pilot that came into the 25th Squadron, as he reported, got his orders to go over to England and bring back an S.E.5a. . . . I made three trips.”98 On one occasion he and Burwell “stopped in London. . . . We went to the hotel where we usually stayed and found Lt. Anderson, in civvies, escaped from Germany. . . . We then went over to the R.A.F. Club and met Capt. ‘Noisy’ [Gwilym Hugh] Lewis. What a dinner, and what a time reminiscing!”99 “The third trip over from England ferrying an S.E.5a I landed at Orly Field outside of Paris, on the 10th of November. We all went into Paris to stay, instead of the place where we should have stayed, at Orly. The next morning we woke up and heard the guns and found ourselves in various and sundry parades. Paris had gone wild.”100

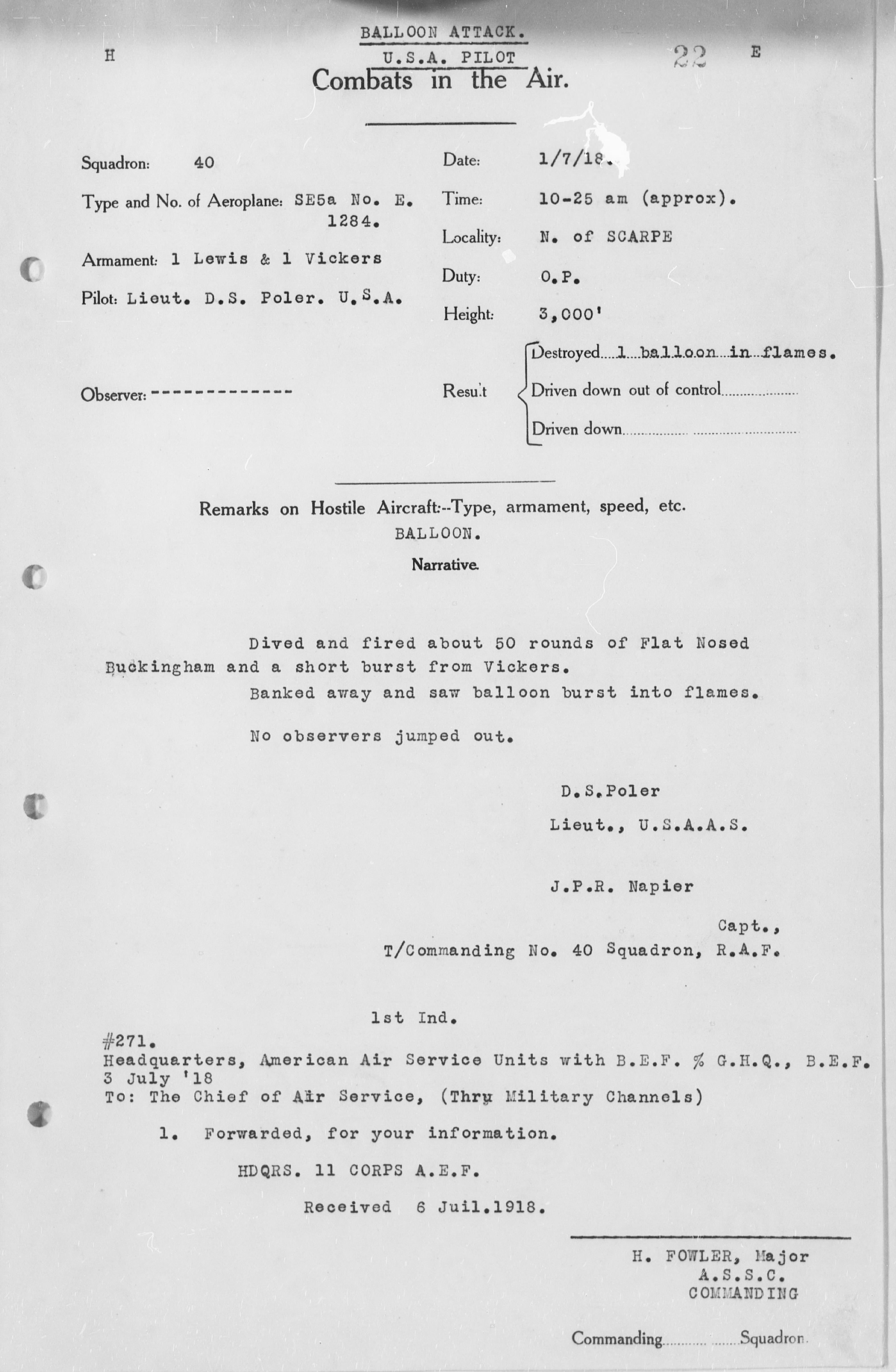

Poler returned to Toul and continued to serve with the 25th Aero after the armistice. Finally, on May 23, 1919, he and other members of the 25th, including Burwell, boarded the U.S.S. Frederick at Brest for the voyage home; they arrived at Hoboken on June 2, 1919; both Poler and Burwell were now captains.101 That same month Poler was awarded the Silver Star. The wording of the citation indicates that American authorities were ill informed about Poler’s service with the R.A.F.: “Poler distinguished himself by gallantry in action while serving with the 25th Aero Squadron, American Expeditionary Forces, in action at Vitrey-en-Artois, France, 1 July 1918, in destroying an enemy kite balloon.”102

Poler resumed his studies at Syracuse University and graduated with a degree in business administration. 103 He worked in the insurance industry, relocating by 1930 to Los Angeles.104 In 1931 the state of New York awarded him their Conspicuous Service Cross.105

Notes

1 For Poler’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Donald S Poler. For his place and date of death, see Ancestry.com, California, Death Index, 1940–1997, record for Donald Swett Poler. The photo is a detail from a photo of the officers of the 25th Aero Squadron.

2 Cutter, Genealogical and Family History of Central New York, vol. 2, pp. 880–81. Family trees at Ancestry.com indicate, without obvious documentation, that the Polers came from the Netherlands.

3 On the Swett family, see Cutter, Genealogical and Family History of Central New York, vol. 1, pp. 344 ff.

4 “Medina High School Graduates 1914.”

5 The Onondagan 1921 indicates Poler graduated after the war.

6 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘Warbirds’,” p. 20.

7 “Cadets Enjoy Their Usual Sunday Rest.”

8 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

9 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘Warbirds’”, p. 20. The men’s heights are given on the verso of their World War II draft registration cards.

10 Deetjen, diary entry for October 9, 1917.

11 Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry (mis)dated October 8, 1917.

12 Ibid. This is one of several accounts of the evening; see, for example, the entry for October 22, 1917, in War Birds.

13 Deetjen, diary entry for October 21, 1917.

14 Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry (mis)dated October 8, 1917.

15 See Deetjen, diary entry for October 21, 1917; and, for the quotation, October 23, 1917.

16 Foss, diary entry for November 2, 1917.

17 Murton Campbell, diary entry for November 5, 1917.

18 Ludwig, Diary, December 3, 1917.

19 Ludwig, Diary, December 4, 1917.

20 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘Warbirds’,” p. 21. Poler is reported as referring to “the Wash at Wareham”; this is presumably a misrecollection or mistranscription of Marham.

21 Both Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, and Jefford, R.A.F. Squadrons, indicate that No. 51 Squadron had F.E.2b’s at this time and make no reference to F.E.2c’s.

22 Ludwig, Diary, December 6, 1917.

23 Ludwig, Diary, December 11, 1917.

24 Ludwig, Diary, December 12, 1917.

25 Ludwig, Diary, December13, 1917. On James Neave and his store in Mattishall, see Taylor, “Church Plain.”

26 Ludwig, Diary, December 15, 1917. “Tiny” is not identified.

27 Ludwig, Diary, December 18, 1917.

28 Ludwig, Diary, December 19, 1917.

29 Ludwig, Diary, December 29, 1917; I have not been able to identify Marjor Money.

30 Wise, Canadian Airmen and the First World War, p 105.

31 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘Warbirds’,” p. 21.

32 Ludwig, Diary, December 31, 1917.

33 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘Warbirds’,” p. 21.

34 Ludwig, Diary, February 11, 1918; 2nd Lt. Watson is not identified, but the instructors were presumably Harry George Smart, Donald Watson, Reginald John Bedlington Benson, Walter Brian Long, and William Gerald Holbrow. See “Gosport School of Special Flying, names of instructors?”.

35 Ludwig, Diary, February 14, 1918.

36 Cablegram 612-S, dated February 16, 1918, includes the commission recommendations for Poler and Ludwig. Wilson is recommended in cablegram 726-S (March 14, 1918); Borncamp, Brader, and Webber are recommended in cablegram 739-S (March 16, 1918).

37 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘Warbirds’,” pp. 21–22.

38 See the last page of the transcription of Ludwig’s diary, where Wilson’s account of the crash has been transcribed.

38a Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

39 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘Warbirds’,” p. 22.

40 “Lieut. Donald S Poler USAS/RCAS.”

41 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 4, p. 299.

42 Lewis, Wings over the Somme 1916–1918, p. 157.

43 Ibid., p. 159 (letter of April 24, 1918).

44 Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” p. 25.

45 Information on Poler’s activities with No. 40 Squadron are based, unless otherwise noted, on the No. 40 Squadron Record Book (RFC/RAF). Quotations are taken from the record book’s remarks column.

46 Two of Lewis’s photos of his plane with himself in the cockpit are reproduced on p. 147 of his Wings over the Somme.

47 Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” p. 25.

48 The relevant combat report includes Landis in the patrol, but he does not appear in the entry for this patrol in the record book. See No. 40 Squadron Combat Reports (RFC/RAF). Poler seems to have forgotten this combat when he supplied information to Sloan in the 1960s, recalling instead that “My first dog fight came on May 21st”; see Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” p. 25.

49 No. 40 Squadron Combat Reports (RFC/RAF).

50 Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” p. 25. On S.E.5a D5968, flown by Donald Frederick Murmann, see Pentland, Royal Flying Corps..

51 No. 40 Squadron Combat Reports (RFC/RAF).

52 Information taken from Pentland, Royal Flying Corps.

53 Poler’s diary entry about his new plane, as reported on p. 25 of Sloan’s “The 25th Aero Squadron,” is dated May 24, 1918, while the squadron record book records his test flight on May 25, 1918, so the two may refer to two separate occasions, but I suspect that the date of the diary entry has been recorded inaccurately.

54 Poler’s diary entry for June 3, 1918, transcribed by Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” p. 25. The record book makes it clear that the move took place June 4, 1918.

55 This information comes from Pentland’s transcription of the relevant casualty report at his Royal Flying Corps; my copy of the record book does not appear to have an entry for this mission.

56 Casualty report for D3505 as transcribed by Pentland at his Royal Flying Corps.

57 Lewis, Wings over the Somme, p. 169 (letter of June 17, 1918).

58 Ibid.

59 Casualty report for D3969 as transcribed by Pentland at his Royal Flying Corps

60 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘Warbirds’,” p. 27.

61 No. 40 Squadron Record Book (RFC/RAF) erroneously records Poler’s plane as E1248 (an R.E.8).

62 Lewis, Wings over the Somme, p. 171.

63 Poler’s diary entry dated June 27, 1918, transcribed by Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” p. 25.

64 Lewis, Wings over the Somme, p. 171.

65 See No. 40 Squadron Combat Reports (RFC/RAF); the combat report can also be seen on p. 22 of Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F. The location is given there as “N. of Scarpe”; Poler specifies “over Vitry” in his diary entry for July 1, 1918, transcribed by Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” p. 25.

66 Lewis, Wings over the Somme, p. 175 (letter of July 11, 1918).

67 Diary entry transcribed by Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” pp. 25–26.

68 See Goettler, diary entry for July 6, 1918.

69 Lewis, Wings over the Somme, p. 175 (letter of July 11, 1918).

70 See the photo of Caldwell with Lewis’s father on p. 163 of Lewis’s Wings over the Somme; and, on Mannock, p. 117 of Adrian Smith’s Mick Mannock, Fighter Pilot: Myth, Life and Politics.

71 Diary entry transcribed by Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” p. 26.

72 Gunby, Sweeping the Skies, p. 63.

73 Cf. Poler’s diary entry for August 8, 1918, as it appears in Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron, p. 26.” The entry appears to elide events that took place over August 8 through August 10, 1918.

74 See Jones, The War in the Air, volume 6, pp. 449–50.

75 Poler’s diary entry for August 8, 1918, as it appears in Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron, p. 26.” Poler recalls having been made “acting Flight Commander” that day; it is not possible to verify this using the record book. It seems somewhat more likely that this appointment occurred after Hind was killed on August 12, 1918.

76 Ibid.

77 I should note that I have found the copy of the squadron record book available to me confusing; pages appear to be out of order, and on some pages no date is provided. However, I believe I have reconstructed the sequence of squadron activities accurately.

78 The events of this day appear in the transcription of Poler’s diary under the date August 11, 1918; the mention of Hind and Wood being missing make it clear that the date should be August 12, 1918.

79 Munsell, “Air Service History,” pp. 65–66 (257–58). Poler’s combat report is referred to in the squadron record book, but I have not been able to locate a copy. Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 46 (239), describes the combat as having occurred at “9:40 A.M. W. of Mons,” i.e., of Mons-en-Chaussée.

80 Gunby is apparently in error when he writes in Sweeping the Skies, p. 65, that these casualties occurred on 40’s “own sector of the front.”

81 This second mission does not appear in my copy of the record book; a page may be missing.

82 The record book, or at least my copy of it, appears to be missing some information about the squadron’s activities on August 13, 1918.

83 See No. 40 Squadron Record Book (RFC/RAF) and No. 40 Squadron Combat Reports (RFC/RAF); and see Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘War Birds’,” p. 23.

84 “Poler, D.S. (Donald S.).”

85 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, pp. 484 and 486.

86 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘War Birds’,” p. 24. See also Poler’s account on p. 26 of Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron.”

87 From Middleton’s typescript diary at the RAF Museum, London, quoted in Hart, Aces Falling, p. 287.

88 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘War Birds’,” p. 24.

89 Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 258 (65).

90 From Middleton’s typescript diary at the RAF Museum, London, quoted in Hart, Aces Falling, p. 287.

91 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘War Birds’,” p. 25.

92 Pentland, Royal Flying Corps: “Sideslipped and smashed u/c on landing but took off again and stood on nose on landing from OP. Capt JL Middleton Ok.” The crashes are not noted in the squadron record book.

93 Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 258 (65).

94 “Lieut. Donald S Poler USAS/RCAS.” And see “Lieut. Paul Verdier Burwell U. S. A. S.” and “Lieut. Reed G. Landis U.S.A.S.”

95 “Attached to No. 56,” p. 320 (diary entry for September 13, 1918).

96 “History of 25th Aero Squadron, (Pursuit),” pp. 4–5; Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” p. 27.

97 “History of 25th Aero Squadron, (Pursuit),” p. 5.

98 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘War Birds’,” p. 26.

99 Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” p. 26.

100 Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘War Birds’,” p. 26.

101 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Dowald [sic] S. Poler.

102 “Donald S. Poler.”

103 The Onondagan 1921, p. 108.

104 Ancestry.com, 1930 United States Federal Census, record for Donald S Poler.

105 Ancestry.com, New York, U.S., Record of Award Medal, 1920-1991, record for Donald S Poler.