(Danville, Pennsylvania, August 1, 1894 – near Charey, Meuthe-et-Moselle, France, September 13, 1918).1

Princeton ✯ Training in England ✯ France & No. 65 Squadron R.A.F. ✯ With the U.S. Air Service and the 213th Aero ✯ M.I.A. / K.I.A.

Frank William Sidler’s great-great-grandfather, Jacob Sittler, emigrated from Germany, initially to New Jersey, eventually settling in Montour County in Pennsylvania, where he farmed land purchased there.2 His son, also Jacob, also farmed, as did his son, Franklin; the latter served on the Union side in the Civil War. His son, William Luther Sidler, born just before the war began, studied at Princeton (class of 1888) and returned to that college for his A.M. degree.3 He was a lawyer and served for many years as register of wills and recorder of deeds in Danville in Montour County. In 1889, he married Mary Elizabeth Divel; she was also of German descent, her mother having been born in Germany, as had been her paternal grandfather.4 The couple had four children; Frank William Sidler was the second child and older of two sons.

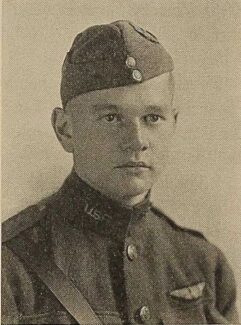

Sidler attended schools in Danville. After high school he enrolled at Mercersburg Academy, a college preparatory school, where he excelled in football, baseball, and basketball.5 He entered Princeton in the autumn of 1915 where, as he had essentially attended high school twice, he was among the older students in the class of 1919.

Princeton

In the spring of 1917 the privately funded Princeton Aviation School was established, and Sidler was among those who applied for it, qualified, and were accepted. Sidler probably, like his classmate William Hamlin Neely, made his first flight in early May 1917 in one of the school’s Curtiss JN-4B’s with instructor John Graham Colgan.6 Around the same time Sidler applied to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and was accepted.7 This meant he would be assigned to one of the six recently created Schools of Military Aeronautics (“ground schools”) scattered around the country. Those responsible for the Princeton Aviation School, in particular James Barnes, were dismayed that Princeton had not been selected as one of the six sites. Barnes went to Washington, D.C., to argue the case for Princeton and, once there, asked some of the students from the school to join him in support. Sidler was among those who travelled down to D.C. on May 23, 1917.8 The effort met with success, and it was agreed that a seventh S.M.A. would be established at Princeton.

In the meantime Sidler, along with the other Princeton Aviation School students, continued his flying instruction at the privately funded school.

Sidler went home to Danville on the first of June for a brief visit; Neely surmised that “he is going home to talk things over with his family. A great many of the fellows have done this & somehow or other the fellows always seem to win.”9 Many of “the fellows” enrolled at the private aviation school, including Sidler, transferred successfully to the government school at Princeton.

Classes at the Princeton S.M.A. commenced on July 5, 1917. Sidler roomed with Neely and Frank John Newbury at Patton Hall, which was used to house the ground school students.10 For nearly eight weeks, through August 25, 1917, the men spent long days learning and practicing Morse code, studying machine guns, attending lectures on bombs, theory of flight, map reading, meteorology, etc.; study was interspersed with various kinds of drill and calisthenics.11 Actual flying was not part of the program.

Government flight training facilities in the U.S., as opposed to what Neely called “theoretical school” (ground schools), were for the most part still under construction, and offers from the Allies to train American pilots in Europe were welcomed.12 According to Arthur Richmond Taber, who was also in this first Princeton ground school class, “a notice was posted on the bulletin board” some time in mid-August “saying that all men who wished to go to Italy for their flying instruction were to sign below.”13 About half of the class of about twenty-six men signed up, evidently including Sidler.14 Preparatory to going overseas, these men were ordered to Mineola on Long Island on August 27, 1917.15 Sidler was able to make a brief visit home a few days later.16 At this point, whether by his own choice or due to a mix-up, he was expecting to go not to Italy, but to France.17 However, on September 18, 1917, the Princeton men, including Sidler, boarded the Carmania—a Cunard line ship being used to transport troops—and set off from New York for Europe as part of the 150-man strong “Italian detachment.”

The Carmania made a brief stop at Halifax where she joined a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, setting out September 21, 1917. The men of the detachment travelled first class and had a good deal of leisure, apart from Italian lessons conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, assisted by violinist Albert Spalding. Towards the end of the voyage, as the convoy entered particularly dangerous waters, the men were assigned to submarine watch duty which was, fortunately, uneventful.

Training in England

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, there was another change of plans. The men were not to go on to Italy but to remain in England and, even worse, as it seemed, to go through ground school all over again. They travelled by rail to Oxford and Oxford University where the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics was located. The “Italian detachment” became the “second Oxford detachment”—a first detachment of fifty American pilots in training having arrived there a month earlier. At Oxford the men spent their first night scattered among the various colleges; the next day they were divided into two groups. Sixty men were assigned to The Queen’s College and ninety, apparently including Sidler, to Christ Church, where they would remain for just over two weeks.18 Then, in the aftermath of some high spirited and bibulous celebrations, the British insisted on moving all the Americans into a single college, Exeter.

Although initially dismayed at having to do another round of ground school, the men of the detachment made their peace with the situation and in retrospect recognized the benefits of R.F.C. training. Their British instructors, unlike those in the U.S., had had war flying experience, and this added considerable interest to the course work. Since the men had already covered much of the material, they did not have to study especially hard, and they enjoyed Oxford hospitality and explored the town and surrounding countryside.

It was rumored that Oxford ground school would last six weeks, but at the end of a month all the men moved on from Oxford. The vast majority were assigned to Harrowby Camp at Grantham in Lincolnshire for a machine gunnery course, but a fortunate twenty, hand-picked by detachment member and Princeton student Elliott White Springs, were assigned to No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford to begin flight training. Sidler, along with Neely and several others from their Princeton ground school class, was among the twenty.19 They made the six-hour train journey from Oxford via Rugby to Stamford on November 5, 1917.20

Assuming Sidler’s experience at Stamford was like that of Neely, it was some time before he was actually flying there. The day after they arrived, the men spent the morning in classes; hopes that they might begin instruction that afternoon were dashed when they arrived at the flying field to find that an instructor, with Springs as his passenger, had just crashed the new Curtiss JN-4.21 The next day was one of the field’s alternate Wednesdays off, and Sidler and Neely occupied themselves by taking a walk. In the afternoon, at the house where the men were quartered, Neely “moved out of the front room with the six occupants up to the third floor where Frank Sidler and I room together.”22 An insufficient number of planes and poor weather meant that there continued to be minimal flying, and both Neely and William Ludwig Deetjen, also at Stamford, writing in their diaries, express frustration at the situation

About a week after their arrival, the men were occupied with a change of quarters. The “vacant private house,” “supposed to be a haunted one,” where they were initially quartered (Deetjen gives the address “60 St. Martin’s Road”), was cold and the plumbing defective.23 In response to complaints the men were moved the evening of November 12, 1917, to the workhouse, literally.24 George Augustus Vaughn remarked that “The place is not half so bad as the name would indicate, on the contrary we like it quite well, except for the fact that it is ten minutes walk to town.”25

Deetjen and Sidler evidently palled around together. The former records in his diary going in to London Tuesday afternoon, November 20, 1917. Deetjen had been refused permission, but he did not mind flouting authority:

Well Frank Sidler & I just naturally went on the 3:40 [train]. We hit the Big Town at 6:50 & went to the Piccadilly Hotel with [instructor] Lt. [Douglas Alwyn Rougier] Chapman & his fiancée Miss Winstan. . . . Later Sid and I went to the Alhambra Theatre & saw “Round the Map.” The Hotels were all crowded and by luck we managed a double room in the Queens Hotel. . . . Wednesday morning we went to Morgan, Grenfell & Co. after a late sleep and breakfast. Also took a buss ride thru the town. And lunch we had with Lt. Chapman & Miss Winstan, followed by a trip to “Chu Chin Chow.” That night we dined with Lts. Hendrich and Hurger [?] of the M.O.R.C. (USA). And in fact had one awful good time in the Trocadero Buffet. Then Sid & I saw “Arlette.”26

Unable to find a room at the railroad hotel, they spent the night in a private house and returned to Stamford on Thursday. The next evening Sidler and Deetjen dined with Chapman and Miss Winstan at the Crown Hotel in Stamford.27 A few days later, Deetjen recounts how on November 28, 1917, “Frank Sidler, Bill Neeley, Ray Watts & I went thru the Blackstone Co’s shell plant here in town.”28 Blackstone’s was originally a farm implement manufacturer; at the outbreak of World War I one of its sites, Rutland Iron Works, apparently in Ryhall Road in Stamford, was taken over by the government and manufactured munitions.29

The next day was Thanksgiving. The men still at Grantham celebrated with a game of (American) football and a banquet, and it seems likely that Sidler, like many others of the now scattered detachment, joined them. Deetjen mentions that “On the 9:30 train a bunch of us went up to Grantham for our Thanksgiving dinner,” but does not indicate who the others were.30

It is apparent from Neely’s and Springs’s log books as well as from Deetjen’s diary that the pace of instruction at 1 T.D.S. began to pick up after the slow start, although there was never as much flying as they wanted. They put in a good deal of time on Curtiss Jennies, some of which had wheel controls like those at Princeton, while some had the stick control that would become standard. Both Springs and Deetjen also note flying DH.6s at Stamford.

Over the course of January 1918, Springs, Deetjen, and Neely left Stamford for other training squadrons and the next stage in their flight instruction, and Sidler almost certainly also did the same. A brief newspaper article from around this time reports that Sidler’s father “has received a telegram . . . stating that [Sidler] is now connected with Squadron No. 86.”31 No. 86 Squadron R.F.C., which did not become operational during World War I, was stationed at Northolt, on the northwest outskirts of London. There is little information about the squadron during this period, but it is apparent from casualty cards from the R.A.F. Museum in London that, despite not being designated a training squadron, No. 86 had Avros and that pilots were being instructed there; at some point No. 86 also had Sopwith Camels, one of the planes Sidler would fly operationally.32 Sidler (assuming the newspaper article is accurate about this posting) was the only detachment member who trained at 86 as far as I can tell, although there were detachment members who trained at other squadrons at Northolt.

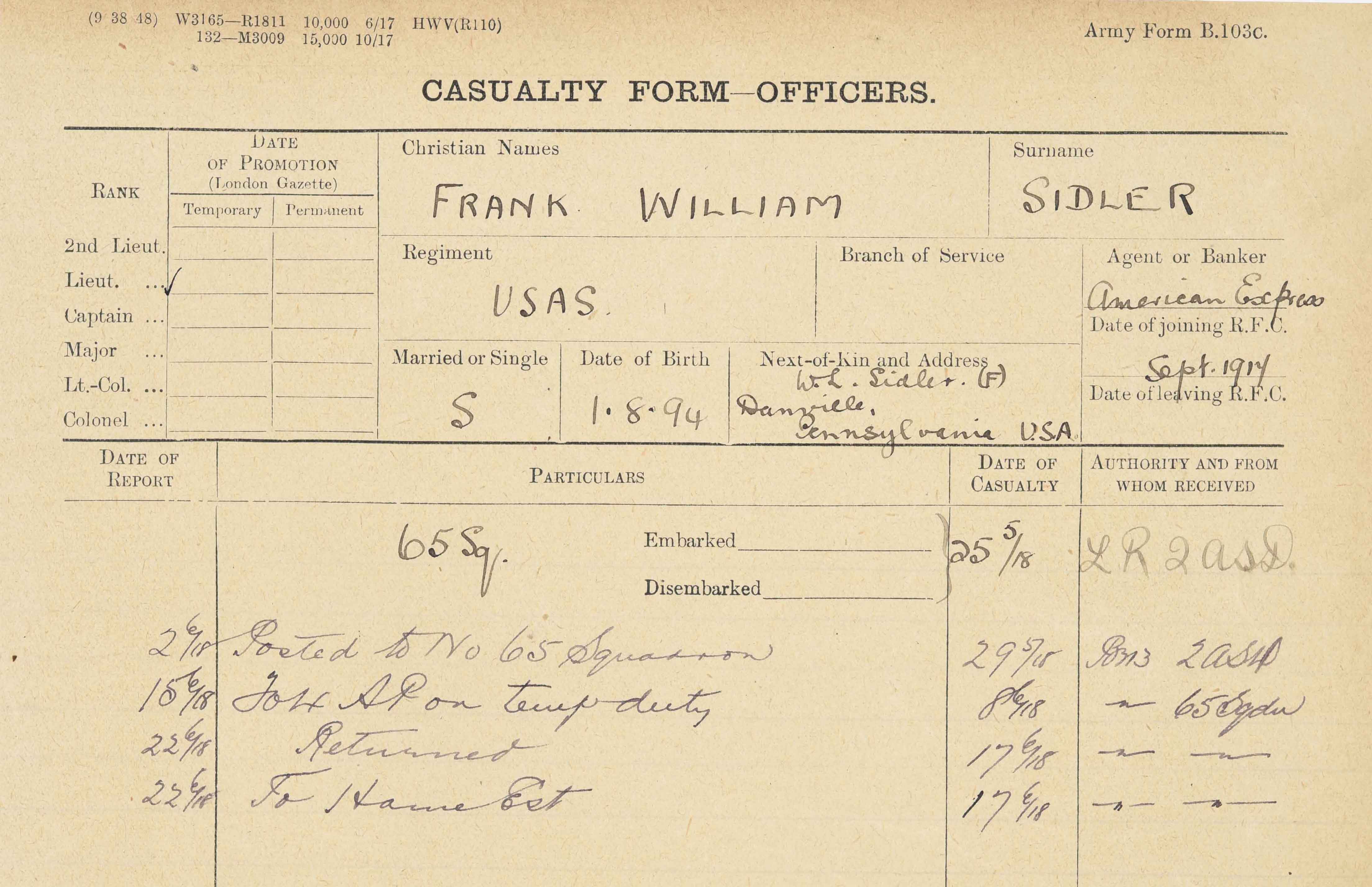

Sidler made good progress. His R.A.F. service record has the annotation “Grad. C.F.S. 3.3.18,” i.e., he completed the next stage of his R.F.C. training in early March 1918. To do this he would have to have fulfilled a number of requirements: flying cross country and at high altitude, completing a substantial number of hours solo, and flying a service machine, perhaps an R.E.8 or a Sopwith Pup. Probably around the same time Sidler also fulfilled the requirements for his commission as a first lieutenant. This information would have been forwarded to the American authorities—never a speedy process—and then Pershing sent the recommendation to Washington in a cable dated March 16, 1918; after the usual delay, the confirming cable from Washington, dated April 6, 1918, brought the good news.33 There was more delay, but finally, on April 15, 1918, Sidler was placed on active duty. He was by this time training at the No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting at Ayr on the west coast of Scotland, where he presumably put in a good deal of time on Camels.34

France and No. 65 Squadron

His training completed, Sidler may, like many others in the detachment, have spent time as a ferry pilot for the R.A.F. (which replaced the R.F.C. on April 1, 1918), although I find no record of this. Finally, towards the end of May 1918, he was sent overseas. On May 25, 1918, he was at the R.A.F. pilots pool at Rang du Fliers, south of Boulogne; from there, on May 29, 1918, he was posted to No. 65 Squadron R.A.F.35 His fellow second Oxford detachment member Field Eugene Kindley had been posted to the same squadron a few days previously; they were the only two men from the detachment to serve with No. 65.

No. 65 was a Camel squadron stationed with the 22nd Wing, V Brigade, at Bertangles, just north of Amiens, which city was, as a result of the first phase of the German Spring Offensive, now only about fifteen miles from the front.36

According to the squadron record book, Sidler went up twice the day after he arrived at No. 65.37 In the late morning of May 30, 1918, he spent twenty-five minutes practicing stunting in Sopwith Camel D9420; late in the afternoon he took up D1817 for forty minutes to do firing practice. He took D9420 up again the next afternoon for more stunting practice. Two days later, on June 2, 1918, he went out late in the morning, apparently alone, on a “special mission” as an aerial sentry, flying Camel B2389 at 17,000 feet; he reported seeing no enemy aircraft during the nearly two hour flight—whose main aim may have been to allow him to familiarize himself with the area from the air. Late the same afternoon, assigned the same Camel, he crashed. According to the casualty report, the engine choked as he was taking off to view French planes at nearby Fienvillers, and he hit a Bristol Fighter.38 Sidler was “OK,” but the plane needed extensive repair.39 Three days later, on June 5, 1918, Sidler made his last recorded flight with No. 65 Squadron; flying Camel D9440, he was again on a special mission as an aerial sentry; again he reported no E.A.

Sidler’s casualty form indicates that on June 8, 1918, he was assigned to “4 AP temp duty” and remained there until June 17, 1918. It may be that this meant that he was at No. 4 Army Aircraft Park at Saint Riquier, about twenty miles northwest of Bertangles.40 This is puzzling, unless he was in some fashion serving as a liaison officer. I note that Thomas John Herbert and Wendell Ellison Borncamp, second Oxford detachment members assigned to No 56 Squadron R.A.F., similarly had temporary duty apparently at nearby anti-aircraft batteries early in their postings.41

Quite unexpectedly, Sidler not only completed his temporary duty on June 17, 1918, he was also on that date posted to “Home Est[ablishment],” i.e., he returned to Great Britain.42 Warren P. Munsell, summarizing Sidler’s service in his account of American pilots who served with the R.A.F., states that on June 12, 1918, Sidler was “Recommended for non-retention as a flying officer by R.A.F.” and that on June 17, 1918, he “Returned to England. Temperamentally unfit for flying.”43 According to an American newspaper account, “early in the summer, while doing aerial scout duty, [Sidler] had a fall caused by a defect in his plane, which sent him to the hospital, where he remained for a couple of months.”44

Either of these accounts would explain Sidler’s leaving No. 65 Squadron, but neither seems entirely credible. Sidler had passed through extensive and rigorous training and any problems of temperament would surely have been detected before this; the American air service, in any case, appears to have had no problem employing him as a pilot. As for the newspaper account, I have not located the R.A.F. casualty card which should have been generated if he had been injured, and other documentation (see below) belies a two-month hospital stay.

With the U.S. Air Service and the 213th Aero

Sidler’s name next appears in an American list showing Sopwith Camels being ferried from Lympne on the south coast of England across the Channel to the American Aircraft Acceptance Park at Orly just south of Paris. Sidler is the ferry pilot for Camel F1316, arriving at Orly on July 2, 1918, just two weeks after he left No. 65 Squadron.45 A few days later Sidler is recorded as flying Camel E1428 to Orly, arriving July 8, 1918.46 This ferrying activity makes credible the report in the American newspaper story mentioned above that Sidler “was in Paris on July Fourth and participated in the observance of Independence Day there.”47 While in Paris Sidler may have taken the opportunity to visit with his aunt, Minnie Leota Wintersteen. Wintersteen (née Divel) was a nurse at the American Red Cross Military Hospital No. 1 in Neuilly, north of Paris.48

Not long after this, Sidler was apparently ordered to report to Toul, where American aero squadrons were being organized for combat.49 He was assigned to the 213th Aero Squadron, Third Pursuit Group, on August 22, 1918.50 He was the only man from the second Oxford detachment to be assigned to this squadron (or to the Third Pursuit Group).

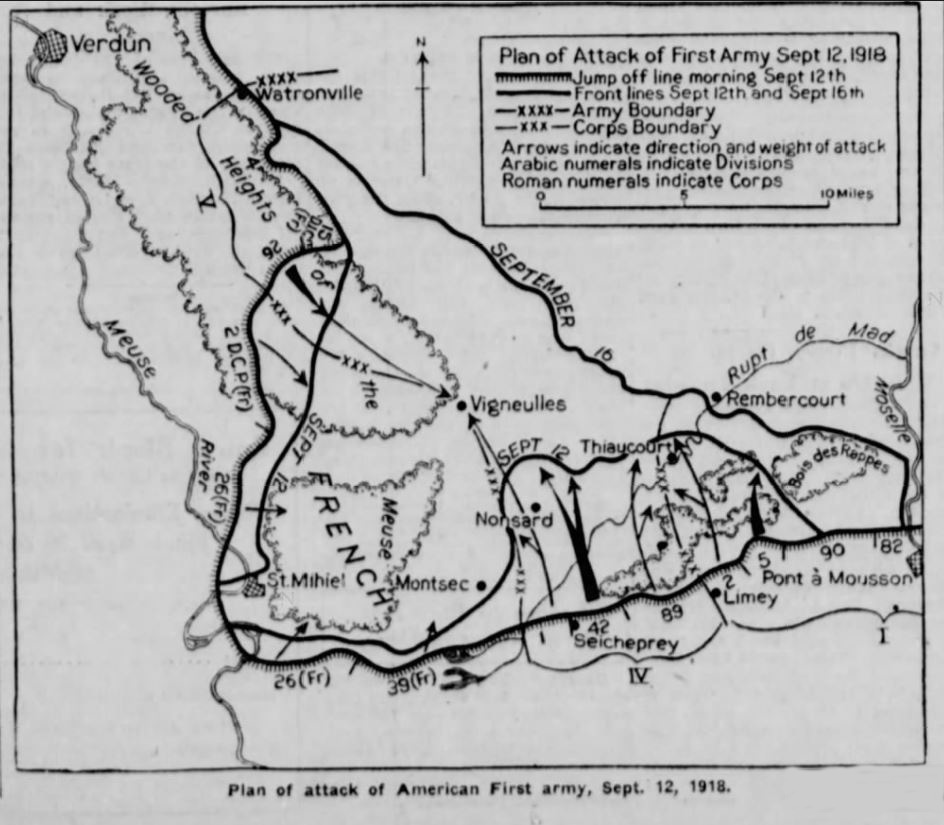

The Third Pursuit Group, whose other squadrons were the 28th, 93rd, and 103rd, was stationed at Vaucouleurs, about twenty miles south of St Mihiel—thus south of the French rather than the American First Army sector of the southern St. Mihiel front. All four squadrons were flying Spads; while the 28th had a number of Spads VII, the 213th, like the 93rd and 103rd, was equipped with Spads XIII.51

Sidler would have flown a variety of planes in the course of his training, and as a Camel pilot he had mastered one of the trickiest of planes to fly. I would guess that the transition to a Spad was no great reach. Whether he had had the opportunity to fly a Spad prior to his assignment to the 213th, I have not been able to discover.

The records kept by the 213th Aero and preserved as volume E.21 in Gorrell’s History and supplemented by records of the Third Pursuit Group in Gorrell’s volume N.11 are less informative and sometimes less accurate than the typical R.A.F. squadron record book. There is almost no information on, for example, practice flights Sidler might have undertaken; on some missions not all the names of the participants are recorded in the daily operations reports; until well into October it is also not recorded which plane a particular pilot flew. Nevertheless, a good deal of information about the squadron and some about Sidler’s activities there can be extracted.

Prior to the opening of the Battle of St. Mihiel on September 12, 1918, the planes of the Third Pursuit Group’s four squadrons were tasked with making small patrols of 3 to 4 planes. According to a narrative history of the Third Pursuit Group, “these were largely in the nature of practice patrols, stress being laid on prompt get away, quick rendezvous, and correct formation flying. Ample opportunity was given the pilot[s] to become thoroughly acquainted with the sector assigned to the Group[,] extending from St. Mihiel on the West to Bey [Bey-sur-Seille] beyond the Moselle River on the east”—this is the entire southern front of the St. Mihiel salient.52

The 213th began flying patrols on August 14, 1918. On August 21, 1918, the day before Sidler’s arrival at Vaucouleurs, the patrols became more strategic in nature: “in co-operation with the 2nd Pursuit Group, a permanent barrage of light patrols, operating at medium and high altitudes, was maintained. . . . The mission of these patrols was to prevent enemy observation planes from making visual or photographic reconnaissance over our back areas and lines of communication.”53 Although the Germans were aware that an attack was imminent and were, in fact, preparing to withdraw from the salient, strenuous efforts were made to keep details of the planned attack hidden. Thus, “It was the policy of our army, at that time, to conceal the strength of our Air Service, so that only small patrols, three to six planes as a rule, were made. . . . At the same time, however, in anticipation of using large formations during the attack, frequent practice patrols were made, consisting of all the available planes in two squadrons flying in the one formation. [T]hese patrols were made well behind lines, unobserved by the enemy.”54

Sidler’s name first appears in the daily operations reports of the 213th on August 28, 1918. He was one of five pilots who set out at 3:35 p.m. on a patrol that lasted just under an hour. Led apparently by Charles Gossage Grey, flight commander of the third flight, they flew first east-northeast to Toul and then northwest to Commercy, about seven miles south of the lines, and back to Vaucouleurs. There was “nothing to report.”55 The next day, in the early evening, Sidler was part of a slightly larger formation led again by Grey. There were seven planes flying at about 11,000 feet; the patrol lasted an hour and forty minutes and took in nearly the entire sector, from Commercy via Dieulouard and Pont-à-Mousson to Bey-sur-Seille and back to Vaucouleurs. Early the next morning, August 30, 1918, Grey, John Will Aiken, and Sidler, on his third recorded mission, flew to Nancy and back.56 On this occasion, Grey reported “having seen one hostile machine in the vicinity of Nancy at an alt. of 5000 meters. Our patrol gave chase and hostile plane turned back over lines.”57 The operations report for that day also records that ten planes practiced formation flying in the afternoon; the names of the pilots are not given, but may have included Sidler.

There were apparently two days of no flying at the turn of the month and then the small formation patrols resumed. Sidler’s name is absent until September 7, 1918, when he is noted testing a plane in the afternoon. The next day he was one in a flight of five planes led by Grey who flew to St. Mihiel and then Flirey before returning to Vaucouleurs; there was “nothing to report” after the seventy-five minute flight.58

The weather in the lead-up to and during the St. Mihiel offensive was miserable, and it is not surprising that the 213th did not fly on the 9th, 10th, or 11th, with the exception of a one-plane reconnaissance patrol flown by squadron commander John Adams Hambleton on the 11th.59

The combined effort of French and American forces to reduce the St. Mihiel salient began early in the morning of September 12, 1918. Orders came to the 213th Aero requiring that “All available planes will leave as soon as possible to bomb and attack with machine guns all concentrations of troops on the road between Waville and Rembecourt [sic; sc. Rembercourt-sur-Mad].”60 This was presumably part of the effort to disrupt the German retreat; the work, which entailed flying at low altitude, was particularly risky. The relevant daily operations report indicates that seventeen planes (“all pilots,” according to the 213th’s narrative history) were involved in this first of two missions that day, setting off shortly after noon; the corresponding reconnaissance report names thirteen of the pilots.61 Although Sidler’s is not one of the thirteen names, it appears from a letter he wrote that day to his brother, Henry Divel Sidler, that he took part: “This morning [sic] we flew through a heavy storm at very low altitudes. The air fairly hummed with machines and sometimes you could see groups of twenty-five and thirty doing nothing but machine gun work and low bombing. It’s a wonderful sight.”62 Given the incompleteness of the 213th’s records, it is possible that there had been an earlier mission (“This morning”), but it seems to me more likely that this was Sidler’s short hand for “earlier in the day” when he wrote his letter that afternoon or evening.

The 213th flew another patrol later in the afternoon of the 12th, focused on the same general area; the operations order explicitly tasks them “with the mission of hampering the enemy’s retreat.”63 Nine planes participated; the daily operations report names eight of them, which leaves open the possibility that Sidler was also on this mission (the corresponding reconnaissance report includes the names of seven of the pilots).64

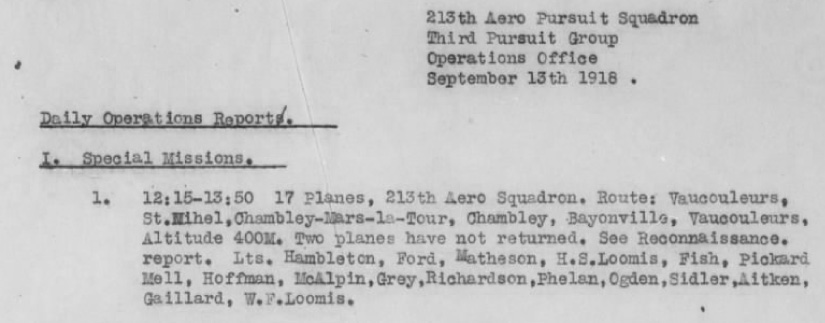

The next day, September 13, 1918, again, a large patrol set out shortly after noon to target the same general area as on the preceding day. Orders received for the 13th stipulated that “The 213th (and 28th, 93rd, and 103rd) Squadron will send all available planes to bomb and attack with machine gun fire the airdrome at Mars la Tour and all concentrations of troops on the road between Mars-la-Tour and Chambley and the road from Chambley to Arnaville.”65 On this occasion, the 213th’s daily operations report provides the names of all seventeen pilots who set out on this patrol at 12:15 p.m., and these include Sidler.66

The corresponding reconnaissance report indicates the planes were flying at only 400 meters and that at 12:50 Kenneth White Matheson attacked two enemy planes at 200 meters “with no apparent result.”67 The daily operations report, which lists only this mission and a trial flight, notes that two planes/pilots had not returned when the report was written, but gives no details.

Later in the afternoon of the same day there was another patrol, or possibly two patrols, not mentioned in the daily operations report but documented in two reconnaissance reports. David Maxwell McClure reports having set out, perhaps alone, perhaps as part of a formation, at 4:50 p.m. and having engaged a Fokker over Mars-la-Tours at 600 meters at 5:15 p.m.68 Aiken also filed a reconnaissance report, in which he states that he set out at 4:45 p.m. and also engaged in a combat, at 700 meters, at 5:15, in the region of Chambley–Waville (just south of Mars-la-Tour). In his narrative Aiken states that he “Fired 50 rounds at an enemy Fokker monoplace machine, . . . Enemy plane was firing on a Spad which was in the formation. While firing on this machine [Aiken] was attacked from the rear, zoomed into clouds and upon coming out was unable to find enemy plane or formation.”69 Apropos apparently of this combat, the (very confused) squadron history narrative notes that “The day was extremely misty with low hanging clouds which prevented our patrol from seeing six enemy machines that attacked from above.”70

M.I.A. / K.I.A.

Both the list of casualties and the list of officers of the 213th Aero indicate that Sidler went missing on September 13, 1918, without providing any details.71 There is apparently a German record of a Spad having been shot down by Gustav Klaudat of Jasta 15 in the vicinity of Vionville (about 2.75 miles east-southeast of Mars-la-Tour) at 1:55 p.m. on September 13, 1918. Norman Franks et al., in their The Jasta War Chronology, have matched this claim to Sidler’s demise, indicating (without naming their source), that Sidler had been flying Spad XIII 15142. Similarly, Trevor Henshaw, in his The Sky Their Battlefield II, matches Klaudat’s claim to Sidler’s Spad, although Henshaw gives Sidler’s plane number as Spad XIII 15089.

I noted above that the 213th Aero’s daily operations report for September 13, 1918, indicates that two planes had not returned from the 12:15 mission when the report was written. One of these was almost certainly that of Irvin William Fish72; it may be that the other was Sidler’s. Or the second not-returned plane may have been one that was simply late arriving back at the aerodrome; the inadequate record keeping makes it impossible to be certain.

What makes this second scenario—that Sidler was not missing from the 12:15 mission— more likely is a detail provided by a letter partly reproduced in a Danville newspaper article; the letter was apparently from Hambleton (“Commanding Lieutenant”), and dated October 7, 1918: “Frank was last seen at Headquartetrs [sic] 4:40 P.M. September 13, 1918. He was seen when taking off from the field of the 3rd Pursuit Group to join his patrol.”73 Although second- or third-hand by now, this passage, if accurately transcribed, suggests that Sidler took part in the late afternoon mission(s) for which we have the reconnaissance reports of McClure and Aiken; it may be that Sidler’s was “the Spad which was in the formation” that Aiken describes as having been under attack at 5:15 p.m.

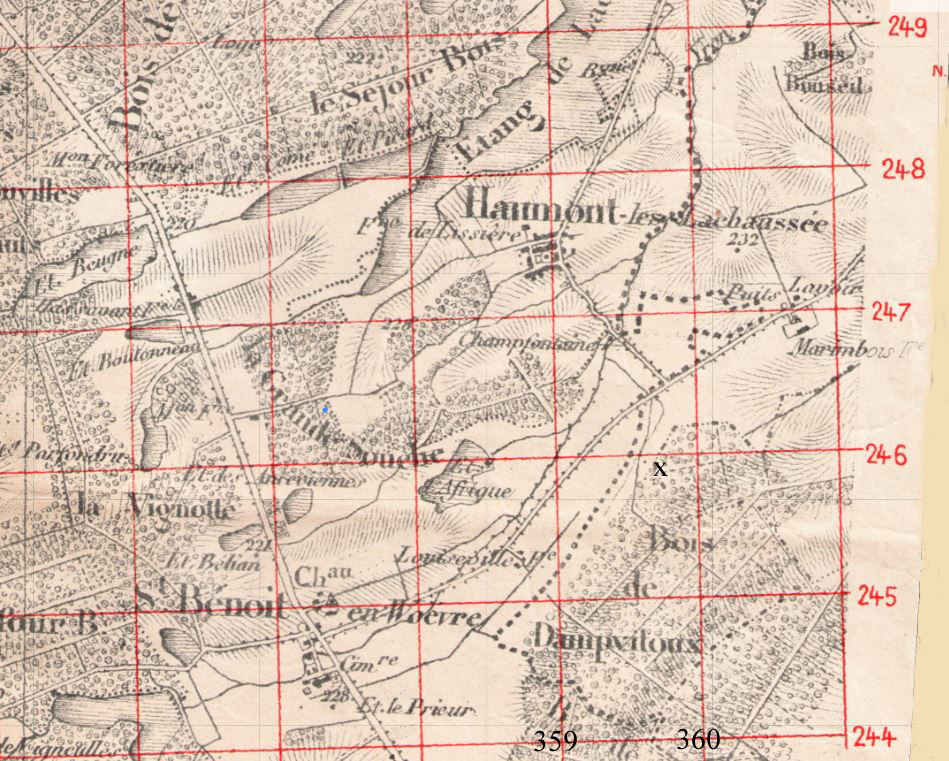

This same newspaper reproduces an account apparently taken from a report by “Harold L. Rodier” (actually Harold Barnhart Rodier) of the medical detachment of the 168th Infantry. The 168th Infantry was part of the 42nd (“Rainbow”) Division, which, by the end of the day on September 13, 1918, had advanced to or very nearly to the Bois de Dampvitoux, just east of Saint-Benoît-en-Woëvre.73a It seems likely that Rodier witnessed Sidler being shot down, although the second-hand nature of the newspaper account makes it impossible to be sure. In any case, the account reads: “‘Aviator Frank W. Sidler with two other Americans were attacked by German planes between — and — on September 13th. After a gallant fight Sidler’s plane fell nose first, and when he was picked up it was found that he had been shot with machine gun bullet through the heart and was probably killed instantly, before he fell.’”74

Two days later, Sidler’s body was buried, presumably close to where he fell. A burial card for this “Grave No. 1, Isolated Cmme. of Charey (M-et-M)” provides map coordinates that indicate the grave to have been in the northern part of the Bois de Dampvitoux, some two and a half miles west of Charey (and some eight or nine miles southwest of Vionville, where Klaudat made his claim).75

The army casualty list of October 14, 1918, reproduced in many U.S. newspapers, lists “F. W. Sidler, Danville, Pa.” among the “Missing in Action” (immediately following “Hilliary [sic] B. Rex, Chestnut Hill, Pa.”).76 Perhaps inevitably, Sidler’s home town appears in some newspapers’ transcriptions of the casualty listings as “Danville, Va.,” which gave his parents false hope that the casualty was not their son.77 Sadly, at the end of October, they received from Minnie Wintersteen as well as from the 213th Aero the news that Sidler had been killed in action.78

After the war, parents of deceased American soldiers were offered the choice of bringing the body home or burial in a cemetery in Europe; Sidler’s parents evidently chose the former.79 Shortly after the war, on May 20, 1919, Sidler’s body was exhumed and reburied at the St. Mihiel American Cemetery at Thiaucourt, not far from the original grave. In 1922, when the cemetery was given its final form, and Sidler was reinterred in grave 35, row 11, block D.80

mrsmcq August 2, 2024

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Sidler’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Frank William Sidler. For his place and date of death, see “Sidler, Frank W.” Note: A record of Sidler’s baptism (Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, U.S., Church and Town Records, 1669-2013, record for Franklin William Sidler) gives his first name as “Franklin” (his paternal grandfather’s first name). “Franklin” is also the name given for him on p. 686 of vol. 2 of Historical and Biographical Annals of Columbia and Montour Counties, Pennsylvania. Other sources, including Sidler’s draft registration and college catalogue entries, consistently give his first name as “Frank.” The photo is from p. 236 of The Nassau Herald: Class of Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen.

2 Information on the Sittler / Sidler family is taken from the article on William L. Sidler on pp. 686–87 of vol. 2 of Historical and Biographical Annals of Columbia and Montour Counties, Pennsylvania.

3 See the entry for William Luther Sidler in Princeton University, General catalogue of Princeton university 1746-1906, p. 284.

4 On the Divel family, see the entry for Judge Henry Divel on pp. 88–89 of Book of Biographies; on Mary Elizabeth Divel’s mother, Barbara née Fleckenstein, see documents available at Ancestry.com.

5 See the entry for Sidler on p. 38 of Mercersbury Academy, Karux 1915.

6 See Neely’s diary entries for May 8 and 9, 1917, and “Frank W. Sidler Joins Aviation Corps.”

7 “Frank W. Sidler Joins Aviation Corps.”

8 O’Neal, “Spirit Ran High in Princeton Flying Corps,” p. 6.

9 Neely, diary entry for June 1, 1917.

10 Neely, diary entry for July 6, 1917; Collins, Princeton Past and Present, entry 31.

11 See Hiram Bingham’s description of the course work on pp. 37–38 of An Explorer in the Air Service.

12 Neely, diary entry for July 5, 1918; Cameron, Training to Fly, pp. 120–22, and pp. 147 ff.

13 Taber, Arthur Richmond Taber, p. 70.

14 The published list of men in the Princeton ground school class that graduated August 25, 1917, (see “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917]) has twenty-six names, but does not include Paul Vincent Carpenter, Edward Matthew Cronin, or John Frederick Bohmfalk, all of whom appear in photos of the class.

15 See Neely’s “Resumé” written on the page for September 6, 1917, in his diary; see also Taber’s letter of August 28, 1917, on p. 75 of Taber, Arthur Richmond Taber.

16 “May To to France in Near Future.”

17 “May Go to France in Near Future.”

18 “Frank W. Sidler of Aviation Corps at Oxford, England.”

19 See Neely’s diary entry for November 1, 1917, regarding which Princeton men went where.

20 See Neely’s and Deetjen’s diary entries for this date.

21 Neely, diary entry for November 6, 1917. Springs, probably mistakenly, indicates the incident took place the preceding day; see Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 49.

22 Neely, diary entry for November 7, 1917.

23 Vaughn, War Flying in France, pp. 29 and 30; Deetjen, diary entries for November 7 and 13, 1917.

24 Deetjen, diary entry for November 13, 1917.

25 Vaughn, War Flying in France, p. 31.

26 Deetjen, diary entry for November 22, 1917.

27 Deetjen, diary entry for November 25, 1917. The woman was perhaps Anita J. Winstan-Ring.

28 Deetjen, diary entry for November 30, 1917.

29 See Key, Official Blackstone Engine Website, part 2.

30 Ibid.

31 “Member of Squadron No. 86.”

32 See casualty cards: “Butler, D.G. (Desmond George)” and “Cowan, J.G. (John Garvin),” both of whom are described as under instruction in Avros; and, for example, “Kelly, V.T. (Victor Thomas),” injured at No. 86 whilst flying a Camel.

33 Cablegrams 739-S and 1049-R.

34 See Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

35 See “Lieut. Frank William Sidler USAS.”

36 On 65’s Wing and Brigade assignments, see Franks and Bailey, “65 Squadron RFC/RAF,” pp. 50 and 51. 22nd Wing and V Brigade were at this time attached to the British Fourth Army, led by Rawlinson. (Numbers for RAF brigades normally corresponded to the number of the army they served. However, the Fifth Army was renamed the Fourth Army on April 2, 1918, in the wake of Rawlinson’s replacing Gough; see Edmonds, Military Operations in France and Belgium 1918, vol. 2, pp. 27–28 and 109.)

37 Information on Sidler’s activities with No. 65 Squadron is taken from RFC/RAF No. 65 Squadron (4 May 1918–31 July 1918).

38 This from the summary of the report provided by Pentland, Royal Flying Corps,

39 Pentland, Royal Flying Corps.

40 On “No. 4 AP,” see Dye, The Bridge to Air Power, p. 178.

41 See “Lieut. Thomas John Herbert” and “Lieut. W. E Borncamp” (casualty forms).

42 “Lieut. Fank William Sidler USAS.”

43 Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 48 (241).

44 “Frank W. Sidler Missing in Action.”

45 History of London Branch of the Supply Section and of Liquidation Section, chart 3, where only his surname is given; see also the entry for this plane in Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, where the pilot’s name is recorded as “Lt FW Sidler.”

46 History of London Branch of the Supply Section and of Liquidation Section, chart 3, pg. 2; see also the entry for this plane in Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File.

47 “Frank W. Sidler Missing in Action.”

48 Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917–1919, 1934–1948, record for Minnie Leota Wintersteen.

49 “Frank W. Sidler Missing in Action.”

50 See the roster of officers on p. 15 of 213th Aero Squadron.

51 See operations report no. 11 et seq. on pp. 225 ff. in Third Pursuit Group, First Wing, First Army.

52 Third Pursuit Group, First Wing, First Army, p. 4

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid.

55 213th Aero Squadron, p. 196.

56 213th Aero Squadron, p. 197.

57 213th Aero Squadron, p. 292.

58 213th Aero Squadron, pp. 199–207.

59 213th Aero Squadron, unnumbered page inserted between pp. 209 and 210.

60 213th Aero Squadron, p. 129.

61 213th Aero Squadron, pp. 2 (narrative history); 210, and 298.

62 This section of Sidler’s letter is read by Terry Diener in his podcast, “The story of World War One Pilot Frank W. Sidler of Danville.” The letter and photos are presumably preserved at the Montour County Historical Society; I have not succeeded in gaining access to them.

63 213th Aero Squadron, p. 130.

64 213th Aero Squadron, pp. 211 and 299.

65 213th Aero Squadron, p. 131.

66 213th Aero Squadron, p. 212.

67 213th Aero Squadron, p. 301.

68 213th Aero Squadron, p. 302. Note: this reconnaissance report gives the start time for the mission as “18:50,” evidently a typo for “16:50.”

69 213th Aero Squadron, p. 303.

70 213th Aero Squadron, pp. 2–3.

71 213th Aero Squadron, pp. 14 and 15.

72 See Fish’s account: “Lieutenant Wounded in Attacking Huns.”

73 “Frank W. Sidler Killed in Action.”

73 See here for the map that appears after p. 164 of American Battle Monuments Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe, showing the positions of the different divisions.

74 Quoted in “Frank W. Sidler Killed in Action.”

75 “Sidler, Frank W.”

76 “Latest Names Announced by Government on U.S. Honor Roll,” p. 10.

77 “Parents Have No Message.”

78 “Frank W. Sidler Killed in Action.”

79 There is presumably a burial file for Sidler among the personnel files at the National Archives in St. Louis. I have not attempted to obtain a copy as the Covid-related backlog of requests there has still (July 2024) apparently not been cleared. The file might well include correspondence with the Sidlers related to the disposition of their son’s body.

80 “Sidler, Frank W.” (verso).