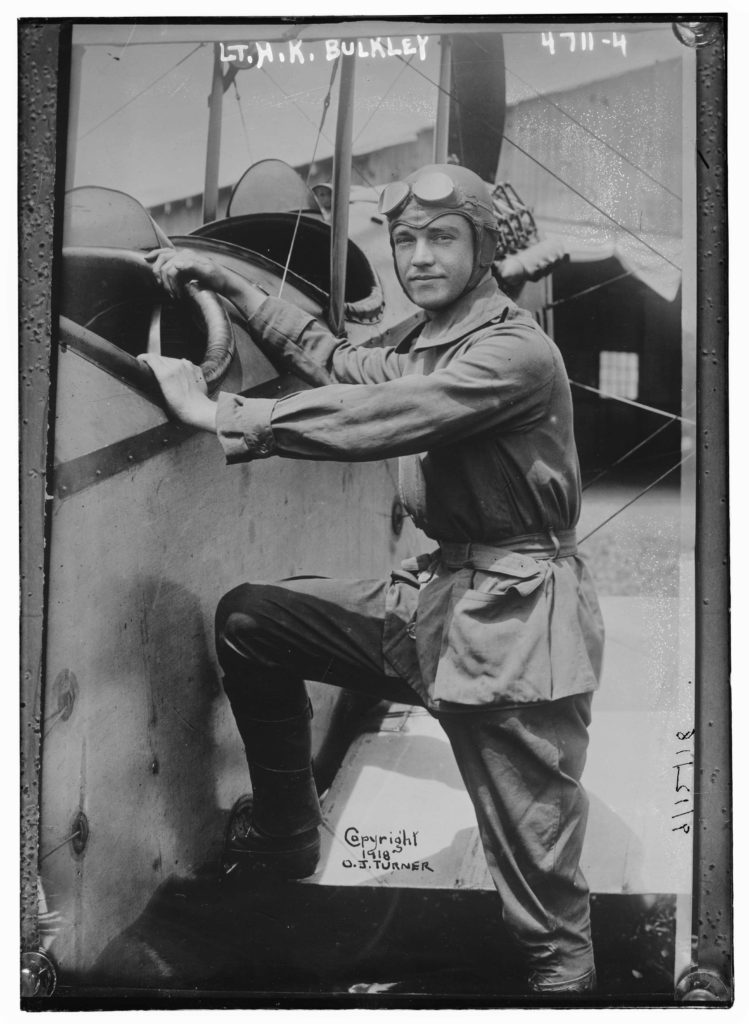

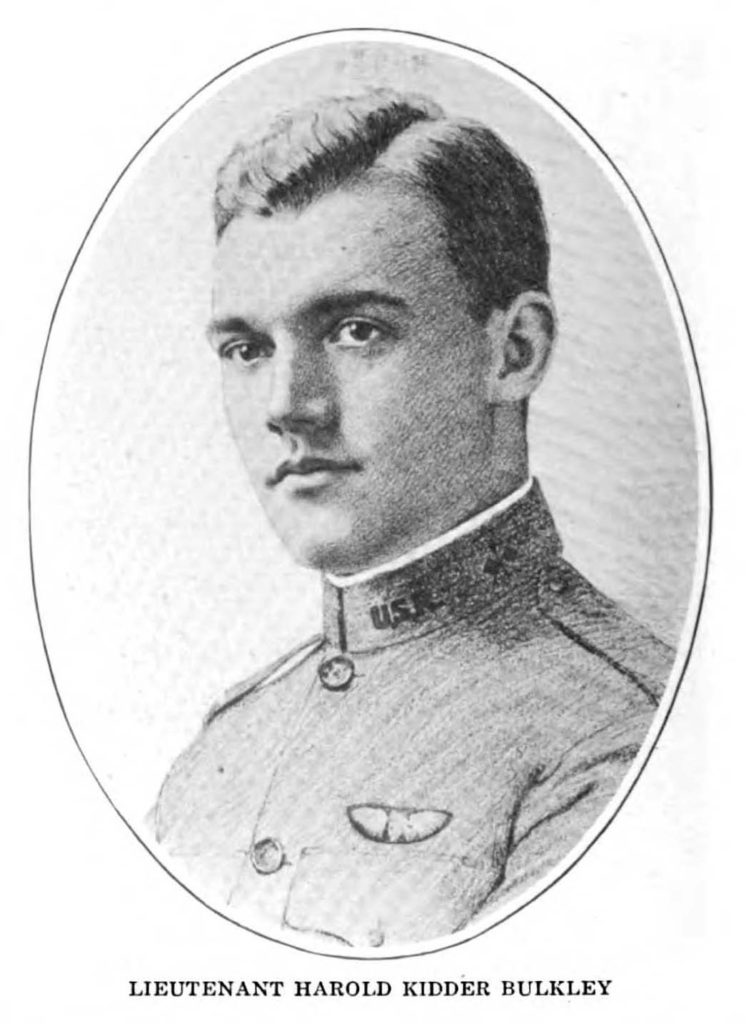

(Englewood, New Jersey, June 30 1896 [1895?] – Hounslow, England, February 18, 1918).1

Harold Bulkley was a direct descendant of the Puritan Peter Bulkley (1583–1659) who founded Concord, Massachusetts (and thus a very distant cousin of mine). His father was a New York banker with Spencer Trask and Co. Bulkley studied at The Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, and then entered Princeton in 1915 (class of 1919).2

At Stamford, as at Princeton, the men trained on Curtiss JN-4s.9 Bulkley was able, despite intermittent bad weather, to put in about thirty hours of flying time during his two months there.10 In early January 1918 Vaughn wrote that “Bulkley and I are still leading our life of ease waiting to be moved on. With no flying and only about a half hour of classes a day, and that between 6 and 6:30 PM, we have a pretty easy time of it, but it is beginning to get monotonous. New Year’s day and the day following we had off, so we went up to Nottingham again and saw a couple of shows, but now we are back on the old schedule.”11

On January 8, 1918, they were assigned to No. 85 Squadron at Hounslow.12 Vaughn wrote that “Harold Bulkley and I are the only ones posted here, and we are very much pleased to be able to stick together. There are two other fellows at the same place, but another squadron.”13 Vaughn and Bulkley were “billeted in a private house near the airdrome. It is a wonderful place, and we are very much pleased with it. We have a room with two real beds in it etc., and are taken in absolutely as members of the family.” They also enjoyed and took advantage of the proximity to London.14 The American cadets and their fellow R.F.C. students were to train on S.E.5s at No. 85 Squadron, but initially “had a dual course on the Avro and [were] checked out in the Sopwith Pup.”15 By mid-February, Bulkley had done four hours dual and thirteen hours solo flying at Hounslow.16 In the meantime, at the end of January, Pershing forwarded a list of men recommended for commissions as second lieutenants, among them Springs, Bulkley, and Vaughn.17

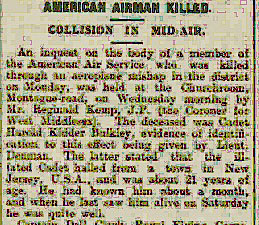

Three weeks later, on February 18, 1918, Bulkley, gliding Sopwith Pup B735 in to land at Hounslow, apparently thought he was too low and pulled up without realizing that an Avro, piloted by a Lieutenant Turnbull with passenger Lieutenant Peacock, was just above him also coming in to land. Bulkley’s plane hit the undercarriage of the Avro; the Pup’s wings buckled and the plane fell and crashed. Bulkley apparently died instantly of a fractured skull. Turnbull and Peacock landed apparently uninjured.18 This much can be gathered from accounts of the inquest that took place on February 20, 1918. Vaughn, in a letter written the next day, added that they “do not give any reason for the two pilots not seeing each other approaching. As a matter of fact there was a large machine right in the middle of the airdrome where they were about to land, and each was watching it, trying to keep away from it as they landed.” In the same letter Vaughn wrote: “It certainly was an awful blow to have [Bulkley] taken away so suddenly and tragically. Since we left the States we had been the closest of friends, and had stuck together all the way through, and since we came to Hounslow together we have been almost inseparable.” Vaughn closes the letter with the remark that “my commission is in London, all ready to be sent down. . . . Poor old Buck’s is there too, but he never knew about it.”19

A cablegram confirming Bulkley’s appointment as a first lieutenant is dated March 9, 1918.20 Vaughn had gone up to London a few days after Bulkley’s death to “see about commissions” and learned that “my commission came through to London with several others last week as a second lieutenant. We are supposed to get first lieutenancies, so they sent them back from Headquarters.”21 Pershing’s cable reporting that a number of the men, including Vaughn, Springs, and Bulkley, had refused the second lieutenancies and recommending them for first lieutenancies, is dated February 25, 1918.22 That the deceased Bulkley was included perhaps resulted from the request for the change having been forwarded to Pershing prior to Bulkley’s death; or perhaps testifies to the difficulties of coordinating communications; or perhaps Vaughn insisted that his late friend receive the appropriate rank, even if posthumously.

Bulkley was initially buried in Heston Cemetery adjacent to St. Leonard’s Church on the northern edge of Hounslow. Later he was reinterred in the Brookwood American Military Cemetery.23

mrsmcq July 25, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Bulkley’s date and place of birth are taken from The Nassau Herald: Class of Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen, p. 63; and Sterling, The Book of Englewood, p. 368. Ancestry.com, New Jersey, Births and Christenings Index, 1660-1931, record for Harold K Bulkly [sic] transcribes the date of birth as “30 Jun 1895.” I have not located a draft registration.

2 Information on Bulkley’s descent is based on records available at Ancestry.com. On Bulkley’s father and on Bulkley’s education, see The Nassau Herald: Class of Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen, p. 63; and Sterling, The Book of Englewood, p. 368.

3 See The Princeton Bric-a-Brac 1919, p. 86, and “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

4 See Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 31.

5 Vaughn, War Flying in France, pp. 17-18. On p. 18a there is a photo of Bulkley and Vaughn at Oxford, Bulkley in the new R.F.C. cap, Vaughn in the old campaign hat, both wearing the white bands marking them as cadets.

6 Vaughn, War Flying in France, p. 28. For the departure date, see Deetjen, diary, entry for November 5, 1917.

7 Vaughn, War Flying in France, p. 30 (letter of November 9, 1917) and p. 41 (letter of November 14, 1917). See also Deetjen diary entry for November 13, 1917, on the Stamford accommodations. It was probably at Stamford, perhaps at the workhouse, that the photo of Bulkley (not Buckley), Frank Aloysius Dixon, and Arthur Richmond Taber reproduced on p. 107 of Sloan’s Wings of Honor was taken; all of them were selected for Stamford.

8 Vaughn, War Flying in France, p. 33 (letter of November 30, 1917).

9 See Vaughn, War Flying in France, pp. 28 and 29.

10 “American Airman Killed.”

11 Vaughn, War Flying in France, p. 38 (letter from January 1918, exact date uncertain).

12 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for George A. Vaughn. I find no such record for Bulkley, but it is apparent from remarks by Vaughn that they were posted together; see Vaughn, War Flying in France, p. 41.

13 See Vaughn, War Flying in France, p. 41 (letter from January 1918, exact date uncertain). I have not identified the two men at another Hounslow squadron.

14 Vaughn, War Flying in France, p. 42 (letter from January 1918, exact date uncertain); p. 43 (letter of January 22, 1918).

15 See Vaughn, War Flying in France, p. 41.

16 “American Airman Killed.” See also “Bulkley, H.K.” for a different breakdown of his flying times.

17 Cablegram 552-S.

18 See “American Airman Killed.” “Bulkley, H.K.” provides the plane’s serial number.

19 See Vaughn’s letter of February 21, 1918 (Vaughn, War Flying in France, pp . 51-52).

20 See cablegram 889-R.

21 Vaughn, War Flying in France, pp. 53 and 54. See also the letter of March 12, 1918, in War Birds and Springs’s letter of March 1, 1918 (Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 96) about the second lieutenancies. McCain’s cable, 746-R, confirming the appointments as second lieutenants, is dated February 7, 1918.

22 Cablegram 650-S.

23 See Hardy, “Harold Kidder Bulkley.”