(Rochester, New York, March 28, 1895 – Rochester, New York, May 3, 1961).1

Cunningham’s father was a carpenter and builder who spent most of his life in Genessee County, New York. Cunningham’s only brother, twenty-two years older, followed his father’s profession. Ken Cunningham studied at the Mechanics Institute and Athenaeum in Rochester from 1913 to 1915 and then in 1915 enrolled at M.I.T. to pursue a degree in mechanical engineering.2 When he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, he was in R.O.T.C. at Madison Barracks at Sackets Harbor, New York. He attended ground school at Cornell, graduating September 1, 1917.3

Along with most of his ground school classmates, Cunningham chose or was chosen to continue his aviation training in Italy. He was thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who departed New York on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania. After a stopover at Halifax to join a convoy, the Carmania had an uneventful Atlantic crossing and docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. There the men learned to their initial dismay that they were not bound for Italy after all, but were to go to Oxford to repeat ground school.

A month later, on November 3, 1917, Cunningham, along with most of the rest of the detachment, travelled to Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gun school at Harrowby Camp. 4

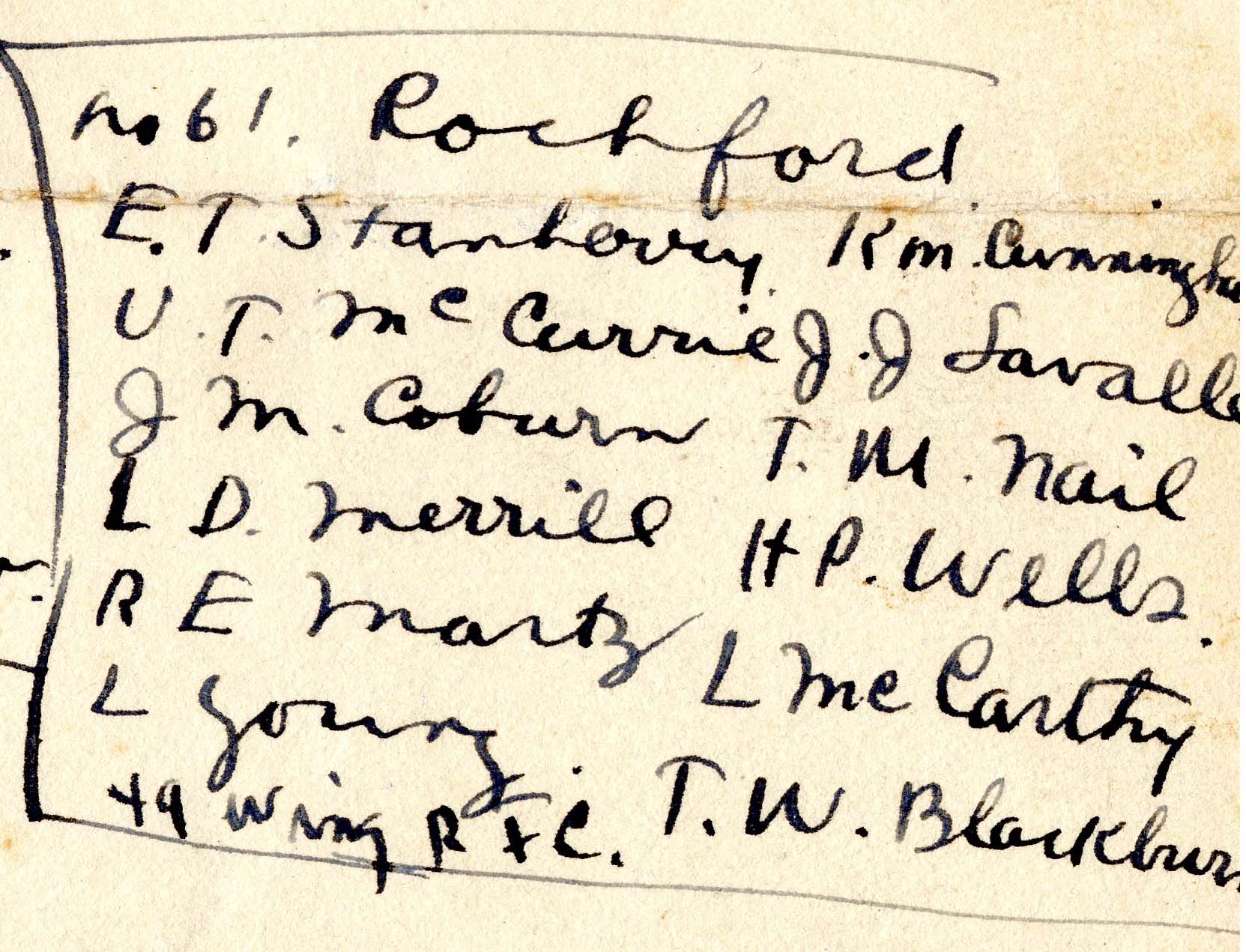

Fifty of the men were selected in the middle of November to go from Grantham to flight training squadrons, but Cunningham was among those who remained at Grantham through Thanksgiving and the end of November.5 Finally, on December 3, 1917, the remaining men were posted to flying squadrons, and Cunningham went with eleven others (Thomas Welch Blackburn, James Mitchell Coburn, John Lavalle, Roy Edwin Martz, Leo McCarthy, McCurry, Linn Daicy Merrill, Thomas M. Nial, Elwood D. Stanbery, Horace Palmer Wells, and Louis McComas Young) to Rochford in Essex.6 The listing of postings for this date recorded by detachment member Fremont Cutler Foss has these men going to No. 61 Squadron, a home defense squadron, but the evidence of some of the men’s R.A.F. service records indicates that some, and perhaps all, of them actually trained with No. 198 Night Training Squadron, which shared the airfield with No. 61 and which had Avros for training purposes.6a A postwar sketch of Cunningham’s military career indicates that he trained at Westcliff-on-Sea, on the coast at the mouth of the Thames estuary. In fact, Westcliff-on-Sea is probably where he was billeted. McCurry, in a letter home, describes being billeted during this period in the Hotel West Cliff there, about three miles due south of the aerodrome at Rochford.6b

By sometime in the first part of February Cunningham had completed enough flight training to be recommended for his commission as a first lieutenant; Pershing’s cable to Washington forwarding the recommendation is dated February 16, 1918. A cablegram dated March 1, 1918, confirmed the appointment.7 Cunningham was by this time apparently at No. 6 Training Depot Station at Boscombe Down, about ten miles north of Salisbury. On February 23, 1918, Jesse Frank Campbell, training at London Colney, noted in his diary that “[Thomas M.] Nial and Cunningham came down today in A W’s from Bascombe Downs [sic].” A few days later, Cunningham took on himself the task of writing to Nial’s parents about the latter’s air accident at Boscombe Down on February 27, 1918.8

Writing a letter home on June 2, 1918, from Turnberry, George Clark Sherman indicates that Cunningham was with him at the No. 1 Fighting School at Turnberry and Ayr on the west coast of Scotland at the beginning of June 1918. Sherman recounts how “The Colonel let us Americans off Thursday afternoon (Decoration Day) . . . Our weekly holiday is from Friday noon until Saturday noon so Cunningham, Heate[r] and I got permission to be absent Friday morning also and went from Ayre [sic] to Glasgow Thursday evening. Friday morning we got up early and took a train to the foot of Loch Lomond and took a steamer from there and went all the way up the Loch and back again that day.”8a

Cunningham’s R.A.F. service record indicates he trained at Turnberry on the use of the Vickers machine gun, and at Chattis Hill (Hampshire) for wireless. It also lists the planes he trained on: the Avro, the BE.2b, BE.2e, and BE.2c, the DH.6, and the DH.4 and DH.9, as well as the Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8.9

Towards the end of June 1918 Cunningham was told to report to No. 55 Squadron R.A.F. at Azelot a few miles south of Nancy.10 No. 55 had been formed as a training squadron in 1916, but in January 1917 was designated a bombing squadron and became the first squadron to be equipped with DH.4s. By early March it was stationed at Fienvillers, France, and in April flew bombing raids during the Battle of Arras. When Hugh Trenchard’s Independent Air Force came into being on June 6, 1918, No. 55 was assigned to it. The purpose of the I.A.F., which initially consisted of Nos. 55, 99, and 104 Squadrons (day bombing), and Nos. 100 and 216 Squadrons (night bombing), was to carry out long-range bombing of strategic targets within Germany.10a

Charles Louis Heater described the challenge faced by the seven second Oxford detachment members, including Cunningham and himself, who were assigned to I.A.F. squadrons at this time, in reaching the base at Azelot: “Nine months of training in England should have given the party of American pilots who left for the Independent Air Force on the last of June an idea of the sort of thing they were running into when they got to France, but most of them were unpleasantly surprised when they were bombed the first night in Boulogne, the second in Paris, the third while on their way to their squadrons in tenders, and several succeeding nights after reaching their stations.”11

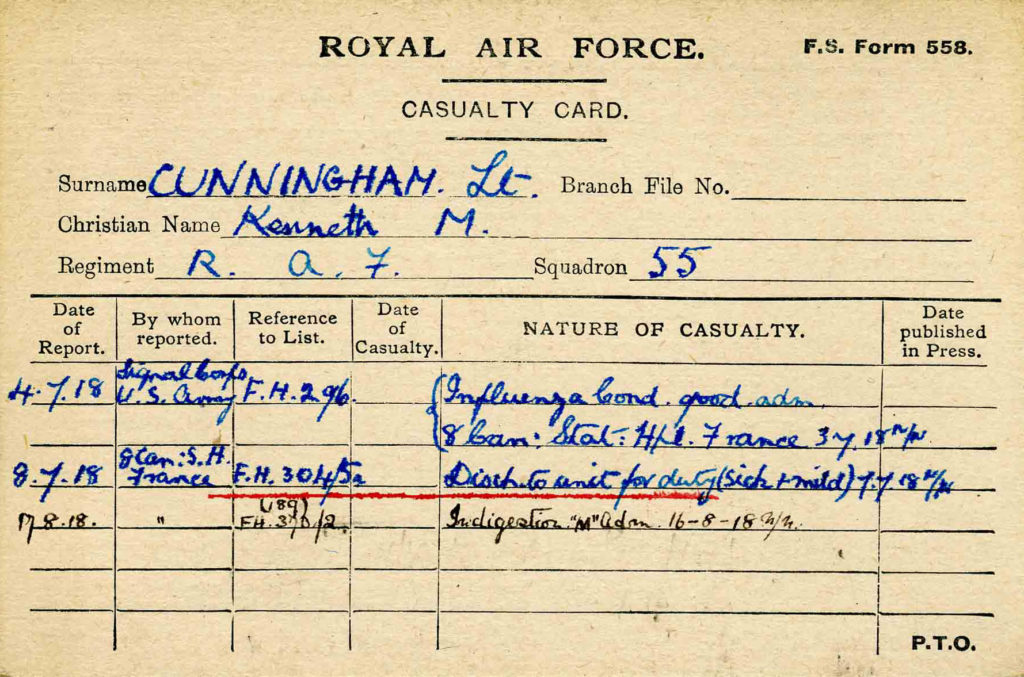

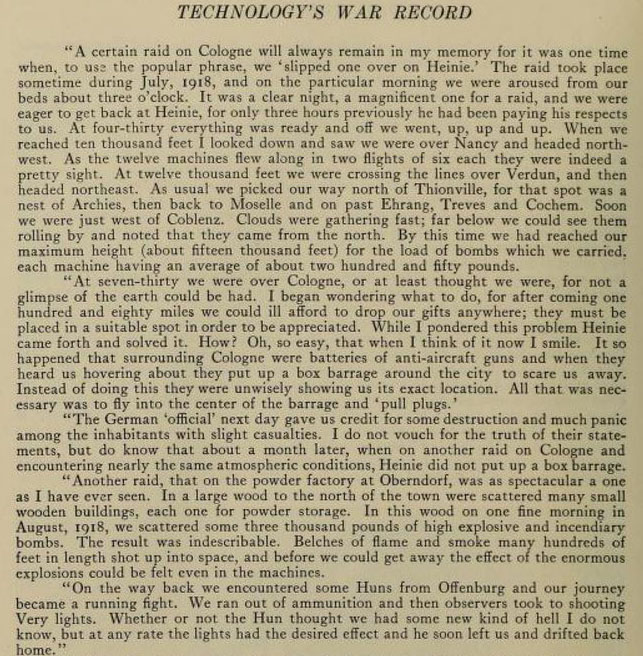

Almost immediately upon arrival at No. 55 Squadron, Cunningham was diagnosed with influenza and admitted to No. 8 Canadian Stationary Hospital at Charmes, about fifteen miles south of Azelot.12 After recovery and a period of orientation, he apparently went out on his first raid on July 31, 1918— this according to the accounts of missions compiled by Rennles in his Independent Force.13 Two formations of six planes each from No. 55 Squadron started at 5:20 a.m. The target was Cologne, approximately one hundred and fifty-five miles from Azelot. Cunningham and his observer, Herbert Hector Bracher, crossed the lines (flying at 13,000 feet), but had to turn back about two hours into the mission because of engine trouble. The next day, August 1, 1918, the target was again Cologne. Although cloud cover prevented their dropping bombs there, the formation, including Cunningham and Bracher, successfully bombed Düren southwest of Cologne. On August 8, 1918, Cunningham took part, again with Bracher, in a successful mission to bomb factories at Rombas. On August 11, 1918, he and Bracher participated in a mission whose primary target was Frankfurt. Their formation, led by J. R. Bell, was intercepted by enemy planes; Bell’s gas tank was hit, and he was soaked in fuel. He turned back, and Cunningham and another plane accompanied him and gave him cover. The three planes dropped their bombs on Buhl aerodrome before returning safely to Azelot. Cunningham’s fifth and apparently final flight took place on August 14, 1918. The goal was again Cologne, but shortly after crossing the lines at 13,000 feet, Cunningham (again with Bracher) turned back due to illness.14

Heater wrote that Cunningham “went on two raids, but both times was very sick and was forced to wash flying on account of his stomach.” Rennles’s account indicates that Heater misremembered the extent of Cunningham’s participation in missions.15 Cunningham himself later provided accounts of two raids, one on Cologne and one on “the powder factory at Oberndorf.” His account of the one on Cologne might be that of August 1, 1918, although some details do not match the account provide by Rennles. His raid on Oberndorf does not appear to match any of the missions he is described by Rennles as having flown.16 Cunningham specifies that it took place on an August morning, but Oberndorf appears to have been a target only in July.17 Perhaps Cunningham mistook the month and Rennles (or the records at his disposal) failed to include Cunningham as a pilot on one of the July raids (July 19 or 20). It is thus possible that Cunningham participated in as many as six or seven missions.

There is a note on Cunningham’s incident casualty card dated August 16, 1918: “indigestion”; perhaps he had not entirely recovered from his bout of influenza.18 Another source indicates that Cunningham was admitted to hospital on the 16th.19 On the same day his observer, Bracher, flew with James Bennett McIntyre; both were killed when shot down south of Mannheim.20

Released from hospital, Cunningham, in Heater’s words, “got a ground job”; this, according to a brief account in an M.I.T. publication, was at U.S. Air Service Headquarters in Paris in the Airplane Design Division.21

After the war Cunningham resumed his studies at M.I.T., graduating in 1922.22 He then returned to Rochester and worked for Kodak.23

mrsmcq June 8, 2017; revised to reflect Sherman’s letter August 6, 2020

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Cunningham’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Kenneth M Cunningham. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963, record for Kenneth Maclean Cunningham. The photo is taken from Technique 1923, p. 61.

2 On Cunningham’s family, see documents available at Ancestry.com; on his father see “Lyman M. Cunningham.” On his education, see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for Kenneth MacLean Cunningham, and the entry for Cunningham on p. 61 of Technique 1923.

3 See “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

4 In the War Birds entries for November 7, 13, and 17, 1917, there are references to “Ken” that I took to refer to Cunningham. The entries for November 6, 13, and 14, 1917, in Grider’s diary make it clear that the reference is not to Cunningham, but to Field Eugene Kindley.

5 Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917, lists the men chosen.

6 Foss, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” (in Foss, Papers).

6a The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, records for McCarthy, McCurry, Nial (where for 196 read 198), and Young. On 198 T.S., see Stedman, “Night Fighter Pilot,” pp. 37 and 46.

6b Ruckman, Technology’s War Record, p. 554; “Air Training in England Exciting.”

7 Cablegrams 612-S and 852-R.

8 “How Trojan was Hurt.” See also Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35,” which places Cunningham at Amesbury on March 23, 1918, when he was placed on active duty.

8a “Lieutenant Sherman is Anxious to Sail.”

9 I take “A.W. (Big)” to refer to the Armstrong Whitworht F.K.8, which, according to Wikipedia, “Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8,” was nicknamed the “Big Ack.”

10 See “List of American Fliers who Served with the Independent Air Forces,” p. 132, which indicates he was assigned to 55 on June 29, 1918.

10a There is considerable controversy surrounding the I.A.F. Chapter 11 of Wise’s Canadian Airmen and the First World War provides an account and an assessment based on original documents that is worth reading.

11 Heater, [Informal account], p. 124.

12 See his R.A.F. service record, cited above, and “Cunningham, K.M. (Kenneth M.).”

13 Rennles’s task in documenting 55’s missions is complicated by there having been two men named Cunningham in the squadron, and there are inconsistencies in naming the two men and in giving their ranks (and identifying them in photos). Rennles does not cite sources, except in a general way in his first chapter, so verification presents a challenge. Neither Miller’s The Chronicles of 55 Squadron, R.F.C. and R.A.F. nor The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924 is sufficiently detailed to be helpful here.

14 Information on Cunningham’s participation in missions is taken from Rennles, Independent Force, pp. 70–71, 76–77, 78, 81, and 87.

15 Heater, [Informal Account], p. 128.

16 See Ruckman, Technology’s War Record, p. 206, which quotes Cunningham’s accounts of the raids.

17 See Rennles, Independent Force, pp. 62–65, and Miller, The Chronicles of 55 Squadron, p. 74.

18 “Cunningham, K.M. (Kenneth M.).”

19 “List of American Fliers who Served with the Independent Air Forces,” p. 132.

20 See entry for this date in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II.

21 Heater, [Informal Account], p. 128; Ruckman, Technology’s War Record, p. 554.

22 “4 Rochester Men M.I.T. Graduates.”

23 See “Kodak Honors 25-Year Folks: 1922–1947.”