(Philadelphia or Boston, September 8, 1892 – Philadelphia or Detroit? June 16, 1957).1

Berry’s father, Albert Berry, came as a child to the U.S. from England and worked initially as a foreman in a woolen mill and later as a government inspector in Philadelphia. In 1885 he married Philadelphia-born Ida Otty Lawson. Norman Kenneth Berry was the last of their four children, all sons. One son died in infancy, and the second oldest son vanished in 1915.2

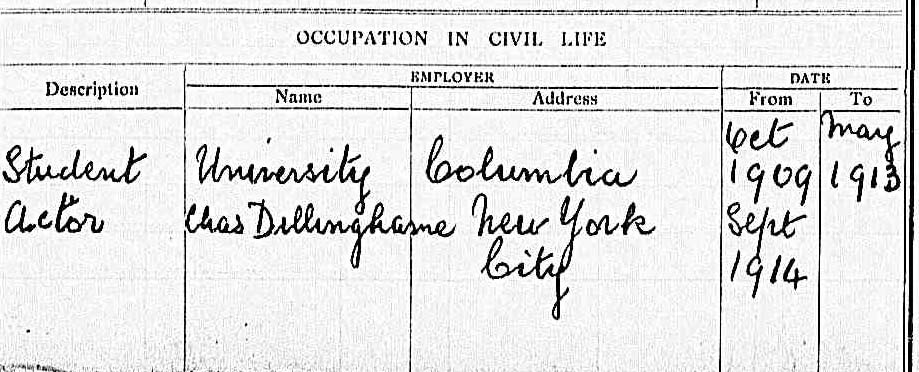

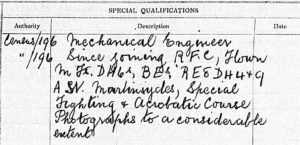

Berry’s R.A.F. service record indicates that he was a mechanical engineer, having been a student at Columbia from 1909 to 1913, and that, starting in 1914, he was an actor employed by “Chas Dillinghame [sic]” in New York City; this was presumably the Broadway producer, Charles Bancroft Dillingham.3 At the end of May 1917 Berry enlisted in the reserve corps.4 By early July he had been able to transfer to the aviation section of the signal corps.5 Around the same time, according to an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer, he had the misfortune to purchase a stolen car while employed at an automobile sales agency in Norristown, near Philadelphia, and was arraigned on a charge of receiving stolen goods.6 Evidently nothing came of the incident, but it is notable that the Inquirer describes Berry as twenty-one years old; his age, like that of a number of his fellow second Oxford detachment members, varied with circumstances.

Berry attended ground school at Cornell’s School of Military Aeronautics, graduating August 25, 1917.7 Along with three quarters of his Cornell classmates, Berry was selected for training in Italy and was thus among the 150 cadets of the “Italian” or “Second Oxford Detachment,” who sailed to England on the Carmania. The ship departed New York bound for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and set out from Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. The men travelled first class and had few obligations other than attending Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, and, once they entered dangerous waters, taking turns at submarine watch. Berry’s acting skills were apparently called upon on at least one occasion. The evening of September 29, 1917, there was a benefit concert for the “Liverpool orphans home for the children of seamen,” and Berry offered a recitation, while other second Oxford detachment members and violinist Albert Spalding, who was also on board, played or sang.8

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned that they were not to go to Italy after all, but to train with the Royal Flying Corps in England. They attended ground school (again) at the R.F.C.’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford for four weeks. As much of their class work repeated material already covered in the U.S., the cadets (as they were now called) did not have to work particularly hard, and they enjoyed exploring Oxford and the surrounding countryside.

In early November 1917 twenty men from the detachment were chosen to begin flying training at Stamford, while the remainder, including Berry, set out by rail on November 3, 1917, for Grantham in Lincolnshire, where they were to attend the machine gun school at Harrowby Camp. Berry’s fellow detachment member Murton Llewellyn Campbell gave an account of their time there in his diary: “We are here . . . for four weeks, two on the Vickers and two on the Lewis. We are treated as officers and are called thus by the English officers. Eight of us in a tent with an orderly to take care of us. Nothing to do but go to the gun rooms and work on the Vickers all day long. We have from 9 to 1 P.M. with one or two hours out for field drill.”9 It was, however, not all work and no play. The evening of November 12, 1917, as Murton Campbell describes it, “was guest night at B15 Mess and believe me, ladies and gentlemen, it sure was some party. It started out O.K. We had an excellent dinner, finished off with a toast, to the King and President of U.S. So far, no farther. Next a couple of British officers together with our gang started a game of Rugby. . . . The band furnished good music to dance by. The dance, however, was too rough to be classed among stag parties or football games. I was dancing with Berry when four ran into us and the whole gang lit on top of me. I nearly broke my ankle.”10

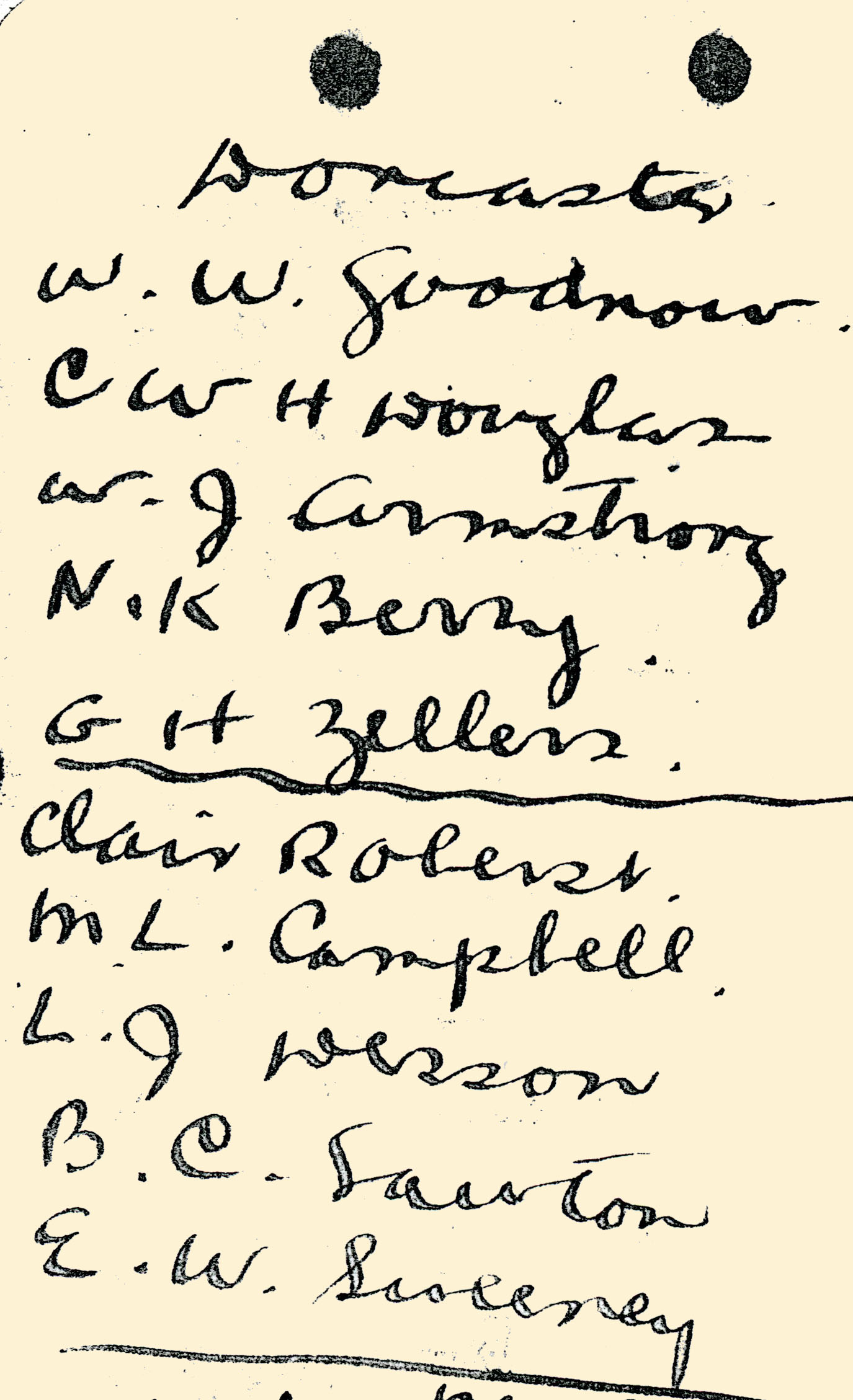

Berry, Murton Campbell, and a number of others did not have their two weeks on the Lewis gun, as it was determined in mid-November that there were places at training squadrons for fifty of the men at Grantham. On November 19, 1917, Berry and Murton Campbell, along with William Joseph Armstrong, Leonard Joseph Desson, Charles William Harold Douglass, Weston Whitney Goodnow, Bradley Cleaver Lawton, Clair Rutherford Oberst, Earl William Sweeney, and George Herbert Zellers, set off from Grantham for Doncaster in south Yorkshire where Nos. 41 and 49 Reserve [Training] Squadrons were located. Berry, Armstrong, Douglass, Goodnow, and Zellers were assigned to No. 41.11 The planes used there for instruction were obsolete Maurice Farmans, much used for elementary training: the Longhorn (MF.7) and the Shorthorn (MF.11), both pusher aircraft, i.e., ones with the propeller located back of the nacelle and cockpit.12

Towards the end of December 1917 a number of the men at Doncaster, probably including Berry, were posted to new training squadrons.13 It had evidently been decided that Berry would train as a bomber or reconnaissance pilot; his R.A.F. service record notes that “Since joining RFC, Flown MFs, DH6s, BEs, RE8 DH4 & 9 A W. Martinsydes.” The first two (MFs and DH.6s) were training planes; the others were all operational planes used for bombing or observation.14

Berry’s R.A.F. service record does not indicate where he received his intermediate training, but a passage in a letter written by Zellers suggests it may have been at No. 20 T.S. at Harlaxton, near Grantham. Zellers, describing his and Berry’s experiences, mentions a man named “Moir, Fryer’s pilot in France whom I have mentioned as being such a good friend of ours while at Harlaxton.”15 Pilot James Prager Moir and the New York-trained Canadian artist Bryant Wilkins Fryer served with No. 12 Squadron R.A.F. in France starting at the end of April 1917. Fryer, trained as an observer, was later posted to No. 41 T.S., where his time overlapped with that of Berry and Zellers; Moir, from the end of February 1918, was at No. 20 T.S. at Harlaxton.16

In any case, Berry’s training evidently moved along smartly. His was one of five names forwarded to Washington by Pershing in a cablegram dated February 28, 1918, recommending the men for commissions as first lieutenants17—which suggests that Berry had passed the requisite flying tests one or two weeks previously, given the typical time lag between such qualification and the actual forwarding of the names. The cable from Washington confirming the appointments is dated March 10, 1918.18

Zellers’s name was also included in these cablegrams, and it appears that he and Berry did a good deal of their training together. At some point, possibly April 4, 1918, they were assigned to the No. 4 School of Aerial Gunnery at Marske-by-the-Sea in Yorkshire; from Marske they were posted to Ayr in Scotland, with a few days for travel and sightseeing in between.19 Sometime in the first half of April Zellers wrote home from Ayr that “Berry and I left Marske last Monday and stayed at Edinburgh until Wednesday. . . . ‘Fuzzy’ Moir, Fryer’s pilot in France whom I have mentioned as being such a good friend of ours while at Harlaxton, lives in Edinburgh. Berry and I called on his mother and had her out to tea.” Zellers, and presumably Berry, anticipated remaining at Ayr for up to three weeks to “get in five hours or more on Bristol fighters”20—the Bristol F.2B Fighter was a two-seater scout and reconnaissance plane.

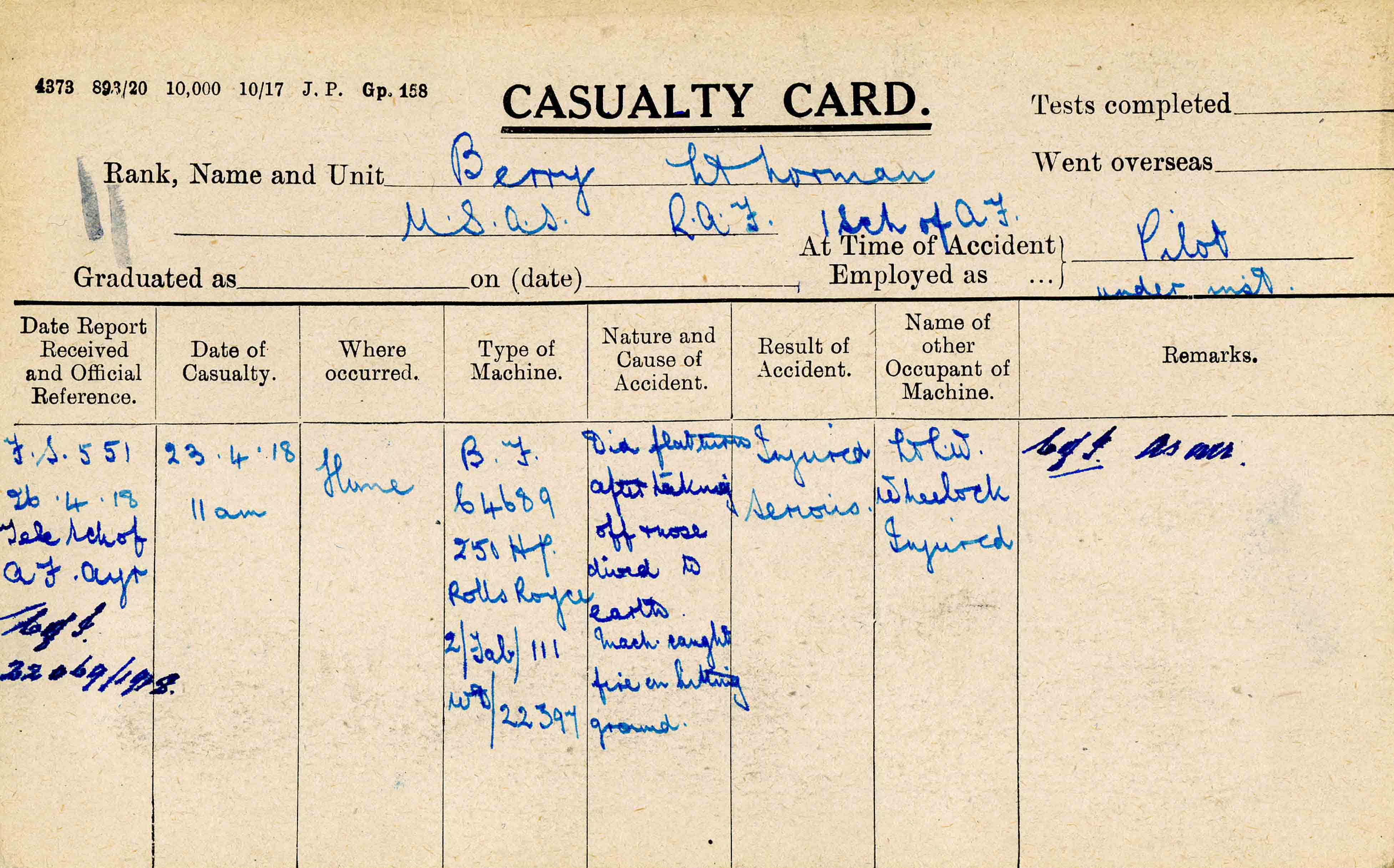

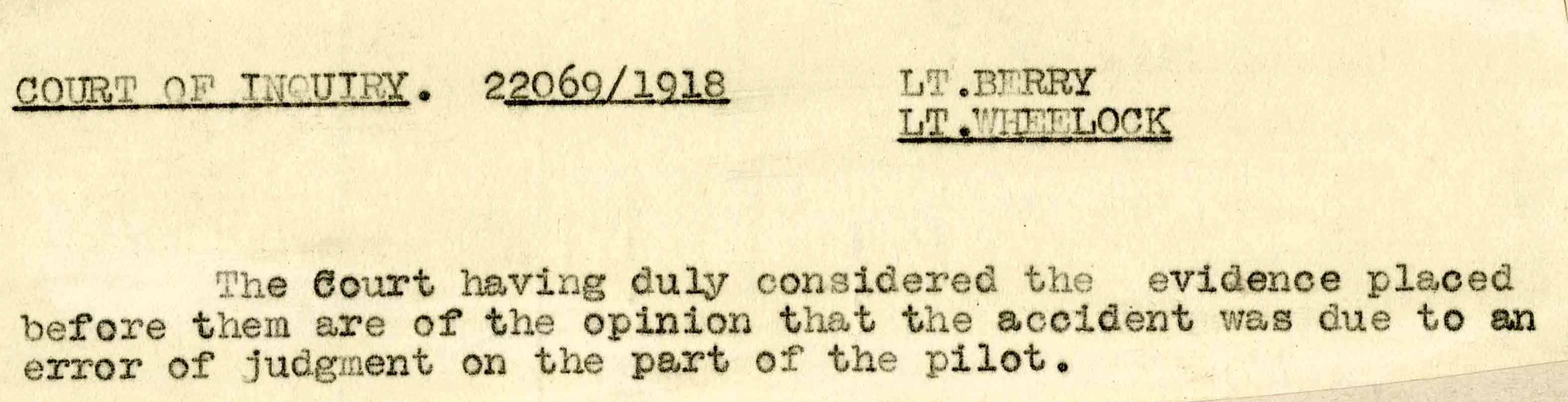

Berry’s career as a pilot was cut short on April 23, 1918, when, flying Bristol Fighter C4689 at Ayr, he was involved in an “Aero accident. Seriously injured.”21 Bogart Rogers, an American who had initially trained with the R.F.C. in Canada, was at Ayr at the time and wrote an account of the incident:

Two fellows started up in a Bristol Fighter, one as pilot and the other in the observer’s seat. In taking off the pilot did a steep climbing turn down wind, which is generally a foolish thing to do. The result was that the machine lost all flying speed, side slipped and crashed right in the middle of the aerodrome. A good crash usually makes an awful noise and this was no exception. The bus lay there for a second or so, and every one from the hangars rushed out toward it. Then—poof—and the whole thing was in flames. The observer had a broken arm and was sort of half hanging from his cockpit. When the fire started he crawled out in a hurry his clothes burning nicely. He rolled over on the ground, put the fire on his clothes out, and then went right back into the flames and dragged the pilot, who was unconscious, out and rolled him over. It all happened so quickly that it’s hard to explain, but the observer surely showed wonderful presence of mind and considerable amount of nerve. Both of them were rather badly burned, but fortunate in getting out at all. You’ve no idea . . . how quickly a machine will catch fire and how completely. The gasoline does it. All that remained after a few moments was a few blackened metal parts.22

Rogers’s description of the aftermath is confirmed by a photo that second Oxford detachment member John Chadbourn Rorison took of the grim wreckage of the plane.23 R.A.F. incident casualty cards record that Berry was the pilot and that Louis Ward Wheelock, of the first Oxford detachment, was the passenger.24

News of the crash circulated, and War Birds includes a second-hand account (both Elliott White Springs and John McGavock Grider were at Hounslow in April).25

A brief article published in July 1918 in a Pennsylvania newspaper reported that Wheelock was “recovering from a broken arm and burns,”26 but I have found nothing about Berry until his name, followed by Wheelock’s, appears on a list of “sick and injured” from the American Military Hospital No. 4 at Liverpool who returned to the U.S on the S. S. Lapland, departing Liverpool on November 22, 1918, and arriving at Hoboken, New Jersey, on December 4, 1918.27 An attendant, Alver Jennings Downs, from an American hospital unit was assigned to Berry, suggesting that he still had a way to go towards recovery; Wheelock was not assigned an attendant.28 Berry was honorably discharged November 26, 1918, at which point he was described as twenty percent disabled.29 In 1919 Wheelock was awarded the silver medal by the U.K.’s Society for the Protection of Life from Fire “For conspicuous gallantry not in action against the enemy . . . [at the] Aerodrome, Ayr, Scotland” and was also “mentioned for valuable service to the Royal Air Force . . . while attached R. A. Force, Ayr, Scotland,” in the Air Ministry List announced January 22, 1919.30

Berry apparently continued his military career for a time after the war. A wedding announcement from March of 1919 indicates that he was stationed at Ellington Field in Texas. 31 I have found little reliable information about him from later years.

mrsmcq April 21, 2017; revised January 29, 2021

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Berry’s date of birth is taken from The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for Norman Kenneth Berry. Emergency contact information on this record links this man to parents Albert & Ida Berry in Philadelphia and to wife Margaret Verna Berry, née Jardine. Comparison with census and marriage records raises questions: census records give later birth dates; “Mrs. M. V. Berry” is listed on the service record, which apparently dates from 1918, as Berry’s wife, but their marriage did not take place until 1919 (see below). Berry’s place of birth is listed on the 1900 census as Pennsylvania. Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, record for Norman K Berry, gives his place of birth as Boston. Until more original documentation (a draft registration, for example) surfaces, these puzzles, as well as ones about his education (see below) remain unresolved. Berry’s date of death is taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., Veterans Administration Master Index, 1917-1940, record for Norman Kenneth Berry, which gives his “residence place” as Philadelphia. The record of his second marriage in 1946, to Josephine H. Otter, indicates he was living near Detroit, which is also where his second wife died in 1992; see Ancestry.com, Ohio, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1774-1993, record for Norman Berry, and Ancestry.com documents related to Josephine H. Otter, née Stoflet. I have not found an obituary for Berry. The photo is a detail from the Cornell School of Military Aeronautics Squadron G photo.

2 On Berry’s family, see records available at Ancestry.com, and “Contractor Vanished.”

3 I have not been able to find a record of Berry in catalogues from Columbia University in New York City from this period.

4 Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917–1919, 1934–1948, record for Norman K Berry.

5 “Enlisted Men Arraigned.”

6 Ibid.

7 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

8 Foss, diary entry for September 30, 1917; see also Ludwig, diary entry for September 29, 1917.

9 Murton Campbell, diary entry for November 5, 1917.

10 Ibid, entry for November 12, 1917.

11 On the men sent to training squadrons, see Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 14, 1917; Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917; and Murton Campbell, Diary, entry for November 19, 1917.

12 Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 301.

13 See Murton Campbell’s diary entries for this period.

14 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for Norman Kenneth Berry.

15 See “A Lancaster Birdman Temporarily in Scotland.”

16 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, records for Bryant Wilkins Fryer and James Prager Moir, and “Lieut. B W Fryer CFA.”

17 Cablegram 657-S.

18 Cablegram 895-R.

19 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for George Herbert Zellers, where the date of his posting to “4SAG” is difficult to decipher.

20 “A Lancaster Birdman Temporarily in Scotland.”

21 “Berry, (Norman).”

22 Rogers, A Yankee Ace in the RAF, p. 93.

23 See Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 41.

24 See “Berry, (Norman)” and “Wheelock, L. W.”; the latter card incorrectly dates the accident as having occurred on April 22, 1918.

25 The War Birds account agrees with that given by Rogers; it appears at the end of the entry for April 14 [!], 1918.

26 “Just Gossip about People.” Wheelock he was apparently back in training at Ayr in September when he was again slightly injured, this time in an Avro; see “Wheelock, L. W. (Louis Ward).”

27 War Department. Office of the Quartermaster General. Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Casuals, Sick & Injured, on S. S. Lapland.

28 Ibid.

29 See Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917-1919, 1934-1948, record for Norman K Berry.

30 “Foreign News,” pp. 28 and 29.

31 See “Miss Jardine Bride of Lieut. Berry, U.S.A.C.”