(Nahant, Massachusetts, June 24, 1896 – Southampton, Long Island, New York, November 13, 1971).1

The birth name of Lavalle’s father, Juan Guillermo LaValle y Schütte, gives some idea of Lavalle’s complex paternal heritage. Juan Guillermo—who took the name John William Lavalle when his widowed mother married an American doctor in Paris—was the grandson, on his mother’s side, of a German immigrant to Peru and, on his father’s, of General Juan Galo Lavalle González Bordallo, an important figure in Argentine military and political history descended from Spanish nobility.2

John William Lavalle came to the U.S. as a boy and attended the Concord New Hampshire St. Paul’s School (founded by George Cheyne Shattuck, Jr., father of his stepfather). He went on to study at M.I.T. and became a prominent architect.3 In 1895 he married Alice Cornelia Johnson, a Bostonian who could trace her family back to early seventeenth-century British immigrants and who was connected to prominent Boston families; her sister was married to a governor of Massachusetts.4 The Lavalles had two children before divorcing around 1910, but the younger child, a daughter, died before she was two, leaving John Lavalle an only child.5

Lavalle, like his father, attended St. Paul’s and then entered Harvard with the class of 1918.6 At Harvard, according to Caroline Ticknor’s account of him in her New England Aviators, the main source of information about his wartime career, he joined R.O.T.C. and was at the Officers’ Training Camp at Plattsburg in the summer of 1916. He was accepted for the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps in April 1917, but, like William Ludwig Deetjen, ran into problems with military bureaucracy—which seems to have decided his last name was spelled “Lavelle”— and was not assigned to ground school at M.I.T. until July; he was one of a group of eight men who are recorded as having graduated September 1, 1918.7

Of those eight, six—Lavalle, Leo McCarthy, Phillips Merrill Payson, Andrew Joseph Shannon, George Dana Spear, and Perley Melbourne Stoughton—chose or were chosen for training in Italy, and these six were among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They left New York September 18, 1917, and arrived at Liverpool October 2, 1917.

There they learned that they were not bound for Italy but instead were ordered to attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University.

Once arrived at Oxford, the 150 men were divided into two groups. Ninety of the men, under their fellow cadet Elliott White Springs, were housed in Christ Church College, and sixty under cadet William Ludwig went to Queen’s. A photo of Lavalle taken by Deetjen suggests he was among those housed at Queen’s. There was initially a fair amount of grumbling about having to repeat ground school; the men were eager to get flying. But they made their peace with the situation and came to appreciate the university town and its environs. Towards the middle of the month they were ordered to exchange their American uniforms for British; around the same time their shenanigans prompted the authorities to move them all (along with members of the first Oxford detachment, who had arrived in early September) into one college, Exeter.8

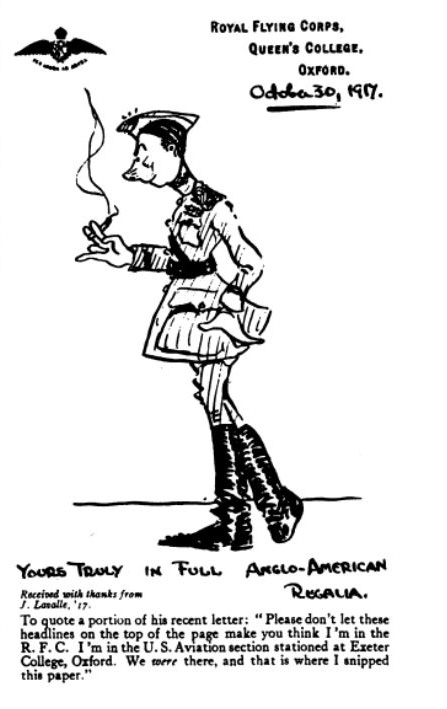

At the end of October, Lavalle sent friends at the Harvard Lampoon (of which he had been an editor) a sketch on R.F.C. Queen’s College stationery depicting himself wearing an R.F.C. cap and uniform, including Sam Browne belt, and noting that he was now at Exeter College.9

On November 3, 1917, most of the detachment, including Lavalle, went to Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend gunnery school at Harrowby Camp. Fifty of these men departed on November 19, 1917, for flying schools; Lavalle was among those who remained at Grantham and completed two two-week machine gun courses, the first on the Vickers, the second on the Lewis machine gun. Lavalle was presumably at Grantham for Thanksgiving festivities, but apparently at some point went down to London and, according to his fellow cadet, Fremont Cutler Foss, “got hell . . . for overstaying leave in London and being done out of 5 £ by a bogus R.F.C. pilot.”10

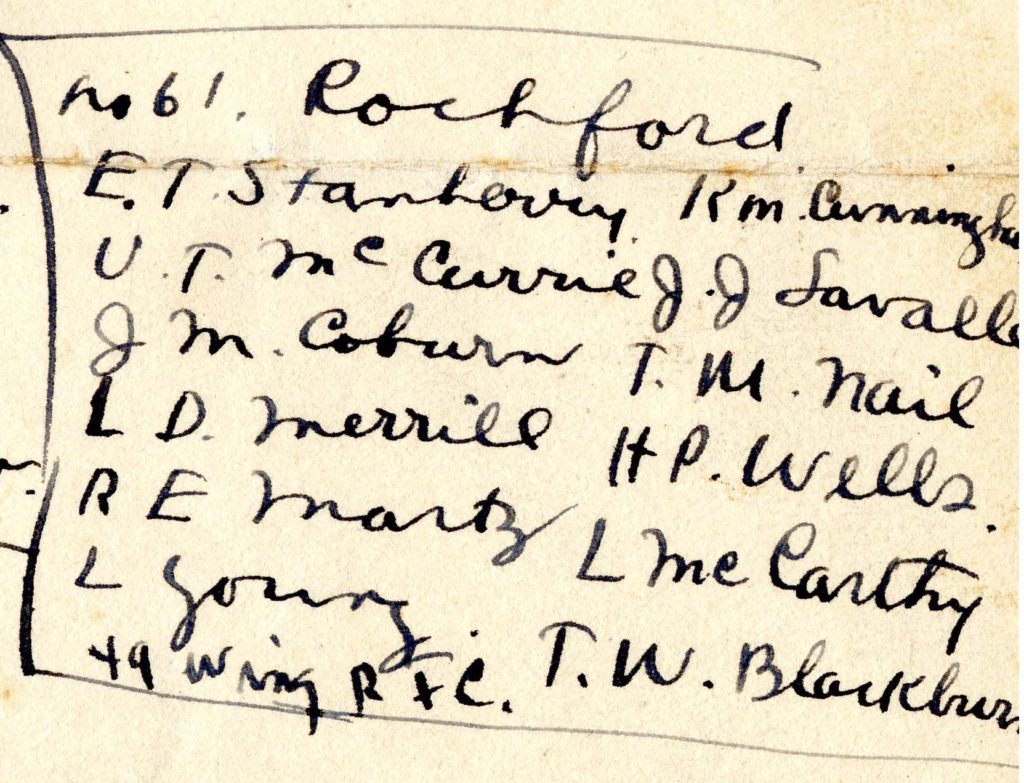

At the beginning December, finally, the cadets still at Grantham were posted to training squadrons. Lavalle went with eleven others (Thomas Welch Blackburn, Jr., James Mitchell Coburn, Kenneth MacLean Cunningham, Roy Edwin Martz, Leo McCarthy, Uel Thomas McCurry, Linn Daicy Merrill, Thomas M. Nial, Elwood D. Stanbery, Horace Palmer Wells, and Louis McComas Young) to No. 61 Squadron at Rochford in Essex.11 This was a home defense squadron flying S.E.5a’s, but Rochford had for some time also been used for training, and there were evidently training planes available.12

By January 1918, Lavalle had done enough dual flying, probably in Avros, to be allowed to advance to flying solo. On January 3, 1918, up alone in a two-seater plane for the third time, he found the weather calm enough and himself confident enough to write a letter home whilst flying, all the while enjoying some Page & Shaw chocolates, a gift from home highly coveted by the men overseas.

Where on earth do you think I am? To tell the honest truth, I’m not on earth at all. I am 5000 feet in the air! All alone! The engine is making such a noise that I can’t hear myself think, but it is very smooth up here at 5000 feet, so I can run this ’bus with my left hand and write to you with my right! I am beginning to think that I am some aviator now, because I can go up and write letters in the air. 13

In the course of his hour and ten minute flight, Lavalle climbed to 10,000 feet, practiced dives and spins, and considered looping but thought better of it. Once back on the ground, he wrote in a P.S.: “Only four more hours to do in the air, before I transfer from ‘C’ flight into ‘A’ Flight, where we learn to do stunts.”

After about two months at Rochford, at the end of January, Lavalle was, according to Ticknor’s biography, ordered to Amesbury. Amesbury itself was not an R.F.C. training site, but there were a number of airfields and training stations in the surrounding Salisbury Plane. It seems likely, but not certain, that Lavalle was posted to No. 6 Training Depot Station at Boscombe Down, just outside Amesbury. He evidently made good progress and by mid-February had completed enough flying hours to be recommended for a lieutenant’s commission. Pershing forwarded the recommendation for “John Lavelle Jr.” in a cable dated February 16, 1918, and the commission was confirmed in a cable sent from Washington dated March 1, 1918; Lavalle was placed on active duty at Amesbury on March 22, 1918.14

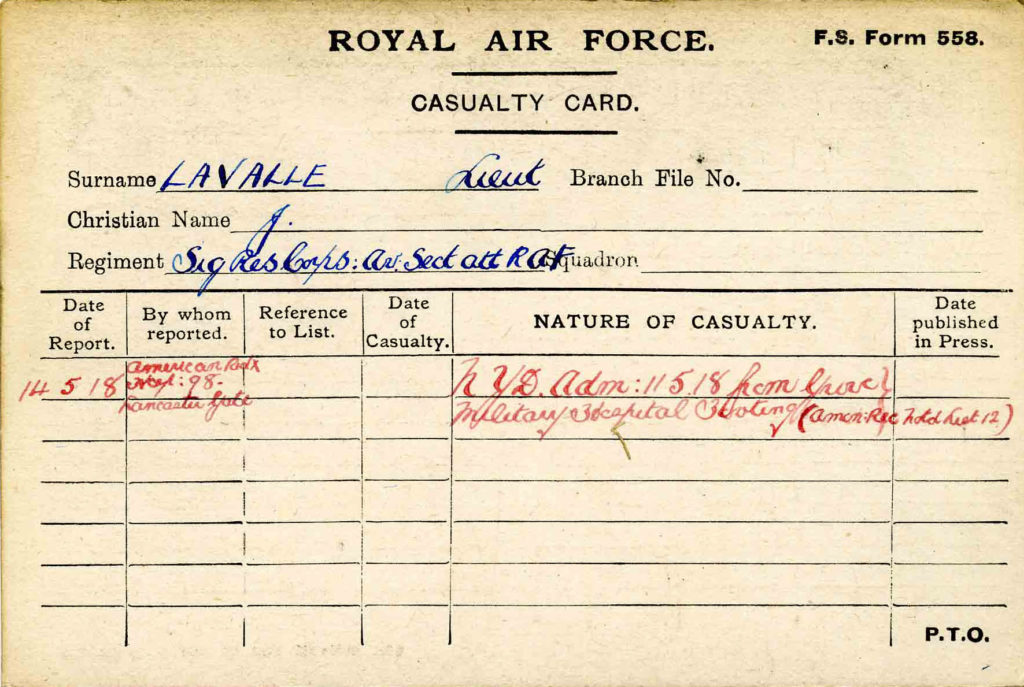

The March 30, 1918, entry in War Birds reads: “I hear that Nial and Lavelle [sic] and Jake Stahl are in the hospital pretty badly smashed up.” Ticknor reports that Lavalle “was in the hospital in London from April 1 to Aug. 8.” I have not found a record of an airplane crash or any other mention of Lavalle’s misfortune beyond an R.A.F. casualty card from May 1918.15 It appears that he was initially sent to the large Grove Military Hospital in Tooting and from there to the smaller American Red Cross Hospital at 98 Lancaster Gate. The abbreviation “N.Y.D.” on the card presumably stands for “not yet diagnosed,” which seems inconsistent with injuries from an airplane crash.

Ticknor writes that Lavalle returned to Amesbury in August and that he went from there to “58 T.S., Cramwell”; this should probably be No. 58 Training Depot Station, Cranwell, in Lincolnshire. She goes on to indicate that he was to join a night-bombing Handley-Page squadron there, but that this did not work out. Whether he was still attached to the R.A.F. and expecting to join an R.A.F. squadron or to be part of the planned American Handley-Page night bombing program (which was still not operational at the end of the war) is not evident. In any case, Lavalle was one of perhaps only two members of the second Oxford detachment (the other was Harvard DeHart Castle) trained to fly the Handley Page, the largest aircraft in the R.A.F. fleet. Lavalle at this point returned to Amesbury as an instructor and was from there posted to Turnberry on the last day of the war. His wait to return home after the armistice was relatively short. He sailed from Liverpool on the Lapland in late November, arriving at New York on December 4, 1918. 16

Lavalle, like a number of his fellow second Oxford detachment members, had interrupted his undergraduate studies; many colleges made provision for students in this situation and allowed them to apply for “war degrees,” which Lavalle evidently successfully did. In the spring of 1919, two war poems written by him, “Combat” and “Over Ypres,” were published in The Atlantic Monthly and The Century Magazine, respectively, and both recount incidents involving British pursuit (rather than bomber) plane pilots. Lavalle went on to study painting at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and in Europe and became a prominent portrait and landscape artist; he also painted a number of World War I aerial combat scenes. During World War II he combined his military and artistic training by serving, among other things, as a camouflage artist.17

mrsmcq February 9, 2019

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Lavalle’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, Massachusetts, Birth Records, 1840-1915, record for John Lavalle Junior. His place and date of death are taken from “John Lavalle, Portrait Painter and Landscape Artist, Dead.” The photo, probably taken in England in the spring of 1918, is from Ticknor’s New England Aviators 1914–1918, vol. 1, p. [281].

2 On Lavalle’s father, his name(s) and descent, see Quirno Lavalle, “La Descendencia del General Lavalle,” Balmaceda, Historias de corceles y de acero (de 1810 a 1824), and Belgrano Lagache, Árbol Genealógico, page for John William Lavalle Schutte.

3 On Lavalle’s father, see “Obituary [for John Lavalle].”

4 On Lavalle’s mother’s descent, see documents available at Ancestry.com.

5 See documents available at Ancestry.com.

6 Ticknor, New England Aviators 1914–1918, vol. 1, p. 280; Mead, ed., Harvard’s Military Record in the World War, p. 564.

7 See “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917],” where his last name is spelled “Lavelle.”

8 On the new uniforms and on the move to Exeter, see War Birds, entries for October 16 and October 22, 1917.

9 Lavalle, [Sketch].

10 Foss, diary entry for December 1, 1917.

11 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.” In Ticknor, New England Aviators 1914–1918, vol. 1, p. 280, for “Rockford,” read “Rochford.” The relationship during World War I between Rochford and nearby Southend, where Ticknor records Lavalle being posted for one day, is not clear.

12 Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, pp. 250–51.

13 [Lavalle], “Youth.”

14 Cablegrams 612-S and 852-R; Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

15 See “Lavalle, J.”

16 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Casual Officers, Air Service, on S. S. Lapland.

17 “John Lavalle, Portrait Painter and Landscape Artist, Dead.”