(Minneapolis, Minnesota, March 12, 1896 – Holley, New York, December 29, 1971) 1

Borncamp’s paternal grandfather had been born in Germany and his grandmother in Switzerland.2 His father was a cider and vinegar manufacturer who became a director of Duffy-Mott.3 Borncamp attended the University of Rochester, in the class of 1918, and was in R.O.T.C. at Madison Barracks, Sackets Harbor, New York, when he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917.4 A month later he, along with Guy Maynard Baldwin, Lloyd Ludwig, Donald Swett Poler, and Donald Andrew Wilson, left Sackets Harbor to go down to Ithaca for aviation training.5 They all graduated from ground school at Cornell on August 25, 1917.6

Along with three quarters of his Cornell ground school classmates, Borncamp was selected for training in Italy and sailed as one of the 150 men of the “Italian” or “Second Oxford Detachment” to England on the Carmania. They docked at Liverpool at the beginning of October to find that they were not to go to Italy after all, but to train with the R.F.C. in England. They attended ground school (again) at the No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford. On November 3, 1917, Borncamp, along with most of the rest of the detachment, left for machine gun school at Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire. At Grantham Borncamp shared a hut with George Atherton Brader, Ralf Andrews Crookston, Burr Watkins Leyson, Clark Brockway Nichol, Poler, Hilary Baker Rex, and Wilson; halfway through the course, when fifty of the men were posted to flying schools, Ludwig moved into the hut as well.7 Borncamp, Brader, Ludwig, Poler, and Wilson, along with Melville Folsom Webber, would continue as a group in their training postings.

On December 3, 1918, the six men arrived at No. 51 Home Defense Squadron at Marham in Norfolk.8 The squadron was tasked with defending that part of England from Zeppelin raids but, like other home defense squadrons, did its share of pilot instruction. Borncamp was billeted with Ludwig, Poler, and Webber at the vicarage, home of Harry Stanley Branscombe, vicar of Marham.9 The squadron, according to Ludwig, flew F.E.2b’s, none of which were dual control; Borncamp thus presumably went up in a plane at Marham for the first time, as a passenger, but did not yet have the opportunity to take the controls. After ten days, on December 13, 1917, Borncamp went with Webber to nearby Tydd St. Mary, where there was a flight from 51 Squadron. A short time later, on December 17, 1917, the six men were posted to No. 192 Night Training Squadron, another F.E.2b squadron, again not dual control, at Newmarket. In any case, Ludwig notes, there were “practically no machines serviceable for flying,” so opportunities to fly were limited.

Christmas offered a cheerful diversion. With forty-eight hours leave, Borncamp went to London with Ludwig, taking advantage of a long wait for a train in Cambridge to visit the colleges. Once arrived in town, they took a room at the Berkeley and enjoyed the theater, dining, and seeing the sights. Arrived back at Newmarket, they learned that they—apparently the six cadets: Borncamp, Brader, Ludwig, Poler, Webber, and Wilson—were to move once again.10 They had initially to report to London, which gave them another opportunity to enjoy the diversions of the city. On the last day of the year, they travelled from London to Gosport to attend the School of Special Flying.

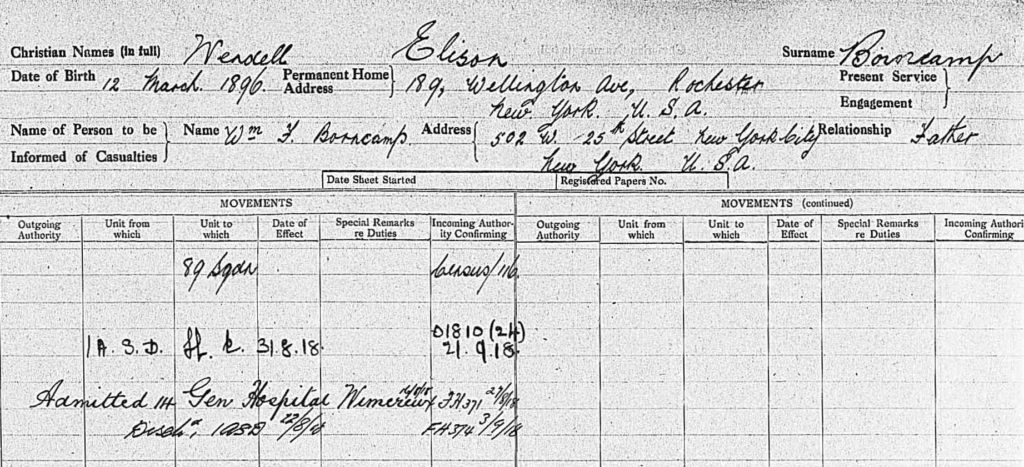

Flight training opportunities improved dramatically at Gosport. Ludwig’s diary records flying almost daily, with occasional time off for bad weather. Assuming Borncamp’s experience resembled Ludwig’s, he flew Avros dual and then solo, and then moved on to an S.E.5 around February 12, 1918. Borncamp’s R.A.F. service record notes that he “Grad C.F.S. 15.2.18,” i.e., graduated from this stage of R.F.C. training.11 Around this time he was recommended for his commission; Pershing’s cable forwarding the recommendation is dated March 16, 1918 (there was typically a delay between the initial recommendation and the cable), and the confirming cable from Washington April 6, 1918. The apparently dilatory nature of this process was frustrating for all concerned.12

If Borncamp continued to be posted with Ludwig and Poler, then he went to Castle Bromwich near Birmingham around February 18, 1918, probably to No. 28 Training Squadron, for further training on S.E.5s.13

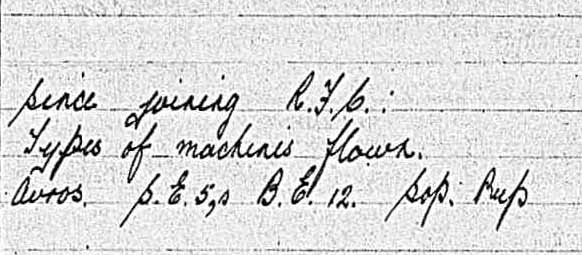

The only record I find of Borncamp’s subsequent training is a cryptic note on his R.A.F. service record: “89 Sqn.” (No. 89 Squadron R.A.F. was a training unit formed in 1917 at Netheravon and disbanded in early July 1918), and the remark that “since joining R.F.C. Types of machine flown. Avros, S.E.5s, B.E.12, Sop. Pup.” It is likely that Borncamp’s training continued to parallel that of Poler, who went from Castle Bromwich to Turnberry and Ayr before serving for a time as a ferry pilot.

Towards the end of June Borncamp was posted to No. 2 A.S.D., i.e., sent to the pilots pool at Rang du Fliers, about twenty miles south of Boulogne, to await orders to join a squadron.14 After a wait of about two weeks, he was posted to No. 56 Squadron R.A.F. on July 14, 1918, joining fellow second Oxford detachment members Roland Hammond Ritter and Thomas John Herbert. All three had trained on SE.5s and were now assigned to an SE.5 squadron.

Herbert had, almost immediately on his arrival at 56, been posted for two days “To ‘N’ Bty AA.”15 Similarly on July 19, 1918, five days after his arrival, Borncamp was assigned “To ‘O’ Batt[er]y AA on temp[orar]y duty.” From a review of casualty forms for a number of his fellow squadron members, it appears that such a temporary assignment to an anti-aircraft battery, perhaps as a liaison officer, was not unusual.16 Borncamp’s casualty form, unlike Herbert’s, does not provide the date of his return to 56, but it presumably occurred within a few days.

No. 56 Squadron had been stationed at Valheureux, about thirteen miles due north of Amiens, since March 25, 1918, i.e., since shortly after the opening of the German spring offensive.17 Valheureux is not many miles from the Somme River, and there are pictures of the pilots of No. 56, including Borncamp, enjoying a picnic and swimming in the Somme towards the end of July. A somewhat more formal photo shows the American and Canadian pilots of the squadron, including Borncamp, taken around August 1, 1918.18

No. 56 Squadron had been stationed at Valheureux, about thirteen miles due north of Amiens, since March 25, 1918, i.e., since shortly after the opening of the German spring offensive.17 Valheureux is not many miles from the Somme River, and there are pictures of the pilots of No. 56, including Borncamp, enjoying a picnic and swimming in the Somme towards the end of July. A somewhat more formal photo shows the American and Canadian pilots of the squadron, including Borncamp, taken around August 1, 1918.18

From Valheureux No. 56 flew offensive patrols in support of the activities of the Third Army (commanded by General Sir Julian Byng) and, on August 1, 1918, joined other R.A.F. squadrons in a successful raid on a German aerodrome at Epinoy. A week later they began assisting Rawlinson’s Fourth Army as the Battle of Amiens opened on August 8, 1918.

The 56 Squadron record book for July and August is missing, so a complete list of patrols flown cannot be reconstructed.19 Nonetheless, Revell, in his High in the Empty Blue, is able, by using personal diaries and other sources, to provide considerable day to day detail of the squadron’s activities; he does not mention Borncamp in connection with any of the patrols flown. Borncamp would perhaps have spent two, possibly three weeks becoming familiar with the squadron and the area before going over the lines.20 A hometown newspaper account of Borncamp’s activities written in 1919 indicates that he did participate in offensive patrols.21

Any such activity was, however, cut short, because, about a month after joining the squadron, Borncamp fell victim to Spanish influenza, which had been circulating in the squadron since at least June 14, 1918, when it sent Ritter to hospital.22 Borncamp was admitted to No. 14 General Hospital at Wimereux (north of Boulogne) on August 16, 1918, and just under a week later, he was discharged to No. 1 A.S.D. at Marquise. It was recommended he be taken off flying status, and he returned to England at the end of the month.23 Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, who was working at American Aviation HQ at 35 Eaton Place in London, noted in his diary on September 1, 1918, that he “went to lunch at the canteen with Morry [Finley Austin Morrison] and Borncamp who is also back from France.” Borncamp was transferred to the Chemical Warfare Service and was still in training when the armistice was signed.24

Upon returning to the U.S., Borncamp worked in the New York fruit, cider, and vinegar company (Duffy-Mott) with which his father had been associated.25

mrsmcq April 26, 2017; updated April 16, 2019, to reflect casualty form; August 20, 2020, to reflect Milnor diary

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Borncamp’s place and date of birth, see U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Wendell Ellison Borncamp. For his place and date of death, see “W. E. Borncamp, World War I Vet, Dies in Holley.” The photo is a detail from a photo of Borncamp’s Cornell ground school class.

2 See 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Henry and Martha M Borncamp.

3 “William F. Borncamp Dies Suddenly.”

4 “1948 Annual Giving Fund Contributors,” p. 11, gives his class year.

5 “Cadets Enjoy Their Usual Sunday Rest.”

6 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

7 Ludwig, Diary, November 19, 1917.

8 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

9 Ludwig, Diary, December 3, 1917; information in this and subsequent paragraphs is based on Ludwig’s diary.

10 Poler’s account on p. 21 of Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘Warbirds’,” suggests that the same six men were together in Newmarket and Gosport.

11 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Wendell Elison [sic] Borncamp. “C.F.S.” stands for Central Flying School, which was at Upavon, but C.F.S. graduation apparently came to designate a stage in flying training regardless of location; a similar notation appears in the R.A.F. service record of the much better documented Callahan, who did not train at Upavon. See also Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of February 14, 1918. See here for the R.F.C. graduation requirements; I find no similar document indicating the requirements for a commission, but there was an understanding that a pilot had to have flown twenty hours solo; see, for example Hooper, Somewhere in France, letters of December 28, 1917, and January 31 and February 14, 1918.

12 Cablegrams 739-S and 1049-R.

13 “Ludwig, L. (Lloyd)” supplies Ludwig’s squadron number. See Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘Warbirds’,” pp. 21-22, for information on Poler’s training.

14 Borncamp’s casualty form, “Lieut. W. E. Borncamp,” provides dates for his service with the R.A.F.

15 See Herbert’s casualty form, “Lieut. Thomas John Herbert.”

16 See also Revell, High in the Empty Blue, p. 324, regarding Majority [Cyril Marconi?] Crowe’s assignment.

17 Revell, High in the Empty Blue, p. 407.

18 The photos are reproduced on pp. 332-33 and 337 of Revell, High in the Empty Blue.

19 Revell, High in the Empty Blue, p. 321.

20 See Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 117, regarding the R.A.F. orientation period for new pilots.

21 See “Rochester Airman Met Great Hun Ace.” Unfortunately, parts of this article are obviously inaccurate, and it is impossible to untangle truth from boosterism.

22 On No. 56 Squadron and Spanish influenza, see Revell, High in the Empty Blue, p. 312; see p. 408 on Ritter being hospitalized.

23 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for Wendell Elison [sic] Borncamp; Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 227 (35).

24 “Rochester Airman Met Great Hun Ace.”

25 See Ancestry.com, New York, State Census, 1925, record for Wendell Borncamp.