(Nashville, Tennessee, February 19, 1890 – Nashville, August 12, 1959)1

Flying Training in England ✯ France

Parrish’s paternal ancestors had settled in Maryland and Virginia in the eighteenth century; his grandfather, physician John Henry Parrish, moved to Alabama around 1845. The family of Parrish’s mother, Hattie Baker, came from England and settled in Philadelphia in the early eighteenth century; her father, engineer and businessman George Oscar Baker, relocated to Alabama in 1855. Both of Parrish’s parents were born in Alabama, and they were married in Selma, but James Parrish moved as a young man to Nashville, where he set up in business, and he returned there with his bride.2

Albert Elliott Parrish was an only child. He attended Wallace University School, a college preparatory school in Nashville, where he was on the football team. He enrolled at Vanderbilt University in 1908 in the class of 1912.3 Whether he completed his college studies is uncertain; the 1910 census lists him not as a student, but, like his father, as a commercial broker for dry goods.4 Parrish excelled at tennis and golf; his name appears frequently in the sports pages of Tennessee newspapers in the 1910s.

When he registered for the draft, Parrish was again or still working as a broker in his father’s dry goods company in Nashville. In early July 1917 he left Nashville for Chicago to take the tests required of applicants to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps.5 He attended ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Illinois in Champaign. His name does not appear on the rosters of graduates, but it is likely that he, along with John Warren Leach, was in the same class as Harry Adam Schlotzhauer and graduated September 1, 1917.6

Many of the men from the Illinois ground school classes of August 25 and September 1, 1917, including Parrish, chose or were chosen to continue training in Italy, and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “Second Oxford Detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. The ship left New York on September 18, 1917, and, after a stopover in Halifax, set out as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but would remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University.

On November 3, 1917, after a month of classes at Oxford, most of the detachment, including Parrish, were sent to Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend gunnery school at Harrowby Camp—the men were in a holding pattern until the R.F.C. could find places for them at squadrons. Fifty men were able to leave Grantham on November 19, 1917, to start flying training, but Parrish was among those who remained at Harrowby Camp until early December and completed both two-week machine gun courses, the first on the Vickers, the second on the Lewis machine gun.

Flying training in England

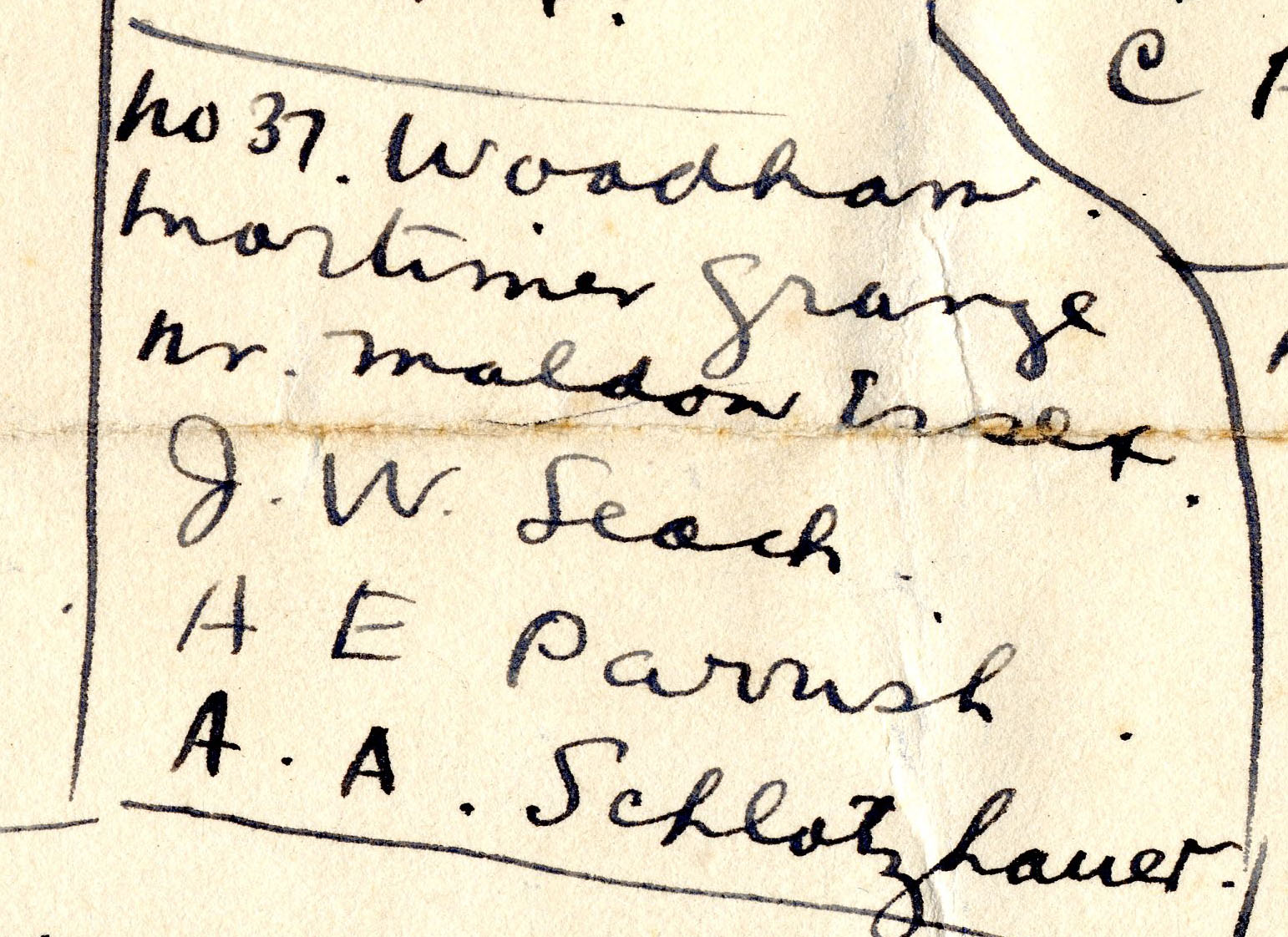

On December 3, 1917, the men still at Grantham were finally posted to squadrons. According to a list drawn up by detachment member Fremont Cutler Foss, Parrish, along with his fellow U. of I. ground school attendees, Leach and Schlotzhauer, was posted to “No. 37 Woodham Mortimer Grange nr. Maldon Essex.”7

No. 37 Squadron R.A.F., commanded at the time by Frederick William Honnet, was a home defense squadron charged with protecting London during German air attacks from the east. Its headquarters was at The Grange, just west of the small village of Woodham Mortimer, and its three flights were based at nearby Stow Maries and Goldhanger. The squadron had on hand B.E.12s, single-seat aircraft designed for reconnaissance and bombing, as well as B.E.2d’s and B.E.2e’s, two-seat biplanes that had been used operationally through early 1917 for the same purposes, but which now served mainly as training aircraft.8 It may have been while he was stationed in Essex that Parrish acquired “a small piece of the wing of the second German airplane brought down on English soil.”9 During a raid by German bombers in the early hours of December 6, 1918, two Gothas were shot down, one in Kent and one near Rochford (second Oxford detachment member Uel Thomas McCurry, training at Rochford at this time, mentions enclosing fabric from this plane in a letter home.10)

Assuming Parrish’s training at No. 37 Squadron was like that of Leach, whose pilot’s flying log book is extant, he would have flown a number of hours in B.E.2e’s piloted by men from No. 37 and then been ready to fly the same type of plane solo. I find no official record of Parrish’s further training. However, a newspaper article from mid-April 1918, apparently based on Parrish’s letters home, states that “Two others who were with [Parrish] during the first stages of his training at Champlain [sic], Ill., are still with him and they have been together throughout their English training.”11 This would suggest that Parrish and Schlotzhauer, like the better-documented Leach, were transferred at the end of January 1918 from No. 37 Squadron to No. 5 Training Depot Station near Stamford, where they could have continued training on B.E.2e’s before moving on to B.E.12s and then R.E.8s. He probably, like Leach, started training on DH.9s and DH.4s in March.

Parrish evidently progressed reasonably rapidly in his training; by early March 1918 he had qualified for his commission as a first lieutenant. The recommendation was forwarded to Washington on March 16, 1918.12 The confirming cable was dated April 6, 1918, and Parrish was placed on active service on April 23, 1918.13

Sometime in April 1918 Parrish, perhaps taking R.A.F. graduation leave, spent time in London where he encountered his cousin by marriage, Clarence Couch Elebash. Elebash, a graduate of Virginia Military Institute who had gone on to receive a medical degree from Tulane University, had sailed for Europe shortly after Parrish and was apparently involved in treating men during the German March Offensive.14 He was afterwards admitted to the Prince of Wales Hospital in London. Rumors reached Alabama that he had been wounded; Parrish was able to reassure relatives that “Dr. Elebash is recuperating from a breakdown, brought on by two weeks’ unceasing strain and work during a recent offensive, and that he is able to do the sights of London and is improving satisfactorily.”15

A further newspaper article refers to Parrish’s having been commissioned “after receiving training in the English royal flying corps at Huntingdon, England.”16 This suggests that Parrish went from Stamford to Wyton near Huntingdon in Cambridgeshire. A remark in the diary of Hilary Baker Rex supports this; Rex was at Wyton, and on June 16, 1918, wrote “Moving on again. I leave with Parrish and [Harvey Donald] Spangler tomorrow for Marske.”17

The first week at No. 2 Fighting School was devoted to class work again: “same old stuff with some of the hot air extracted,” as Rex described it in his diary entry for June 8, 1918. Assuming Parrish’s experience was similar to Rex’s, he would initially have gone up with an instructor in an Avro to be tested and then have put in a number of hours piloting DH.9s, practicing formation flying and fighting; on one occasion Parrish went up in a DH.9 as Rex’s passenger.18

On the last day of June 1918 Rex noted in his diary that he was in London: “Parrish and I (after the usual hours of red tape) managed to get away from Marske yesterday. We report at Chattis Hill, Stockbridge, wireless telephony School Monday. The interim we are spending sort of clandestinely in London. No one knows where we are and we are supposed to have permission from Hdqtrs. to come here, but we didn’t have time to get it.” They were short of cash, but by July 3, 1918, were able to travel to Chattis Hill. “We managed to get some money, or at least Parrish did, and got out of London without being pinched. This course is not bad.” C. G. Jeffords, in Observers and Navigators, describes how “Experimental work on speech transmission was under way in the UK by May 1915”; field trials in wireless telephony were undertaken in France in 1917. The Wireless Experimental Establishment at Biggin Hill started training Bristol Fighter and DH.4 and DH.9 crews in January 1918; in early April 1918 the training was “taken over by the newly established Wireless Telephony School which moved to Chattis Hill” around April 15, 1918.19 Such technology must have seemed a huge advance over the Morse code transmission and reception the second Oxford detachment members had spent so many hours learning and practicing.

After finishing up at Chattis Hill, Rex and Parrish were once again in London, awaiting orders. On July 11, 1918, they had lunch at the Overseas Officers’ Club with “Dr. Elebash, who’s a darn nice fellow.”20

France

Around this time, Parrish’s and Rex’s names appeared in a long list of men ordered to “proceed from London, England, to Issoudun, France, reporting upon arrival thereat to the Commanding Officer for duty in connection with aviation.”21 Issoudun, in the Loire region of central France, was the location of the American 3rd Aviation Instruction Center; Parrish would presumably have trained on American built DH-4s there and practiced the skills required of an observation pilot.

On September 13, 1918, Parrish reported to the U.S. 8th Aero Squadron.22 Seven men from the second Oxford detachment had already been with the 8th Aero for nearly a month: Newton Philo Bevin, Edward Addison Griffiths, Anker Christian Jensen, McCurry, Edward Russell Moore, John Howard Raftery, and Rex.

The 8th Aero was an observation squadron flying DH-4s.23 On the last day of August, in preparation for the St. Mihiel Offensive, the squadron had been assigned to the IV Corps Air Service of the American First (and at that time only) Army; they were stationed at Ourches-sur-Meuse, about eight miles due west of Toul.24

The combined effort of French and American forces to reduce the St. Mihiel salient had begun early in the morning of September 12, 1918. The 8th Aero was assigned to assist the IV Corps’s 1st Division, which was at the westernmost part of the American line on the south front of the salient. The squadron C.O., John Gilbert Winant, reported that on the 12th and 13th planes of the 8th Aero “were in the air for thirty-six hours and thirty minutes . . . and twenty-four separate missions were accomplished”25—and it was from one of the missions on the 13th, the day Parrish arrived at the squadron, that Rex and his observer failed to return. Whether Parrish was called upon to take part in these missions is not known: the operations reports that might provide details of individual flights appear, unfortunately, not to have been preserved.

The IV Corps Air Service did not participate in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, but remained initially at Ourches.26 On September 29, 1918, IV Corps squadrons, including the 8th Aero, moved a few miles east to Gengoult aerodrome near Toul. From there the 8th Aero flew extensive photographic missions as well as voluntary bombing missions.27 “One of the duties assigned at this time was to photograph the entire Corps front to a depth of ten kilometers, an area of about six hundred square kilometers.”28

Parrish with his observer, Edward Henry Hobbs, Jr., from Alabama, helped to make a significant contribution to this effort on October 9, 1918. Their squadron mate, Raftery, flew one of the protection planes during this mission, and he wrote a lively account of the day.29

A photo mission was scheduled to take a strip of German territory important in the eyes of our army, but early morning clouds and drizzle seemed to prophecy a dead day. . . . Around lunch-time, encouraged by a bit of blue sky here and there Lieut. Moore the flight leader decided to chance it. . . and three machines taxied onto the field in position, Moore pilot and [Gardner Philip] Allen observer in the leading machine containing the camera, Parrish and Hobbs in the left-hand protection machine, and Raftery and [John Harold] Mulherin in the right-hand protection machine. After five minutes wait the fourth bus still persisted in spouting water from its leaky radiator so Moore, determined on braving the Huns with only three planes, waved his hand. Three throttles opened together, and three D H 4’s bounded across the field and up into the air. . . . when at Pont-a-Mousson Moore sighted eight Fokkers coming in from Metz, he cocked his guns once more to make sure and continued North up the [Moselle] river. Our formation at the required 10,000 feet manoeuvered to directly over Arnauville [sic; sc. Arnaville], the starting-point, and the Huns manoeuvred toward our formation. As our formation turned N.E. they came over on top, turning behind to follow at about 500 yds. . . . the Hun leader dived. He came in pretty close behind the formation, pulled up and let loose with both guns. On Moore’s machine a landing wire snapped on one side of him, a flying wire waved in the breeze on the other side and his elevators received a shower of bullets. Disregarding these white streaks of tracers shooting by on all sides, Moore kept directly on his course and Allen in the observers cockpit without making a move toward his guns to defend himself continued snapping his pictures and changing plates. . . .

The protection planes did their job, and the Fokkers eventually departed. The next hazard was anti-aircraft fire, which “cut still another rip in the leader’s wings. . . . At Lake Lachausee the last picture was snapped and the leader Moore, banking to the left, started the formation for home. In his cockpit Allen carried the hard-earned pictures which turned out to be clear overlapping photos of the exact territory required.”30

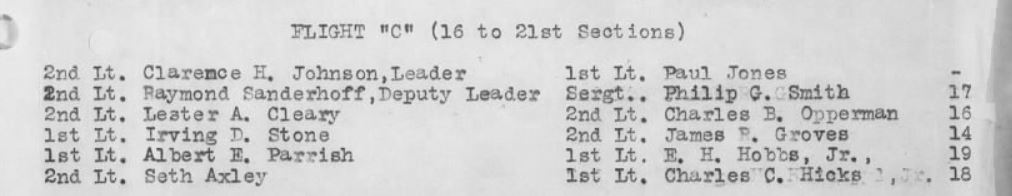

Parrish’s flying protection for Moore suggests he, along with Raftery may at that time have been in Moore’s A flight of six teams of pilot and observer. A roster from October 20, 1918, shows Moore and Raftery still in A flight; Parrish and observer Hobbs, flying DH-4 # 19, are listed in C flight.31

On October 23, 1918, the 8th Aero moved once again, this time about ten miles northeast to Saizerais where, again, they undertook voluntary bombing missions.32 The 8th was now part of the Air Service of the recently formed Second Army, whose proposed task—cut short by the armistice—“was to begin a general offensive leading to the capture of Metz and the gateway into Germany proper.”33 On October 25, 1918, the 354th Aero Squadron, an observation squadron preparing to become operational, also moved to Saizerais to work with the Second Army, and Parrish, with his observer Hobbs, as well as Bevin of the second Oxford detachment and Albert Cyril Rothwell of the first, were among the experienced officers from the 8th Aero immediately assigned to it.34 The 354th, like the 8th, appears not to have preserved records of individual missions, but their squadron history provides a general description of their activities:

On October 28 with fourteen planes on hand eleven pilots and fourteen observers on the rolls, the first operations were begun, consisting of reconnaissance in front of 92nd [Infantry] Division, which at this time extended from Villier-sous-Preny, about three kilometers west of the Moselle River, to Eply about ten kilometers east of the Moselle River; artillery reglage with the 349th, 136th, 350th, and 351st Field Artillery alternately. Also there were infantry liaison maneuvers with the 92nd Division, 183rd Brigade. . . . The number of teams scheduled to go across the lines varied from day to day according to the movements of the enemy. An average of ten teams were scheduled daily. In addition to these, an Alert and an Alternate Alert team were on duty at Group Headquarters from 6:30 to 16:30. By November 11 when the Armistice was signed, it might be said that the 354th had just struck its full stride.35

Parrish was among the men fortunate enough to be able to return to the U.S. early in 1919. He, along with Bevin, left Bordeaux on January 6, 1919, on the Wilhelmina, and arrived at Hoboken on January 19, 1919.36 Not long afterwards, he presented Hobbs—who had been able to return home even sooner than Parrish—with a cane made from the propeller from a plane they had flown together.37 Back in Nashville Parrish once again took up golf, his name again appearing frequently in the Nashville sports pages. He initially worked as a cotton broker, perhaps continuing his father’s business; later he went into real estate.38

mrsmcq September 10, 2021; revised April 28, 2023, to reflect Rex’s diary

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Parrish’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Albert Elliott Parrish. His place and date of death are taken from “Bert Parrish, National Life Ex-Aide, Dies.” The photo is a detail from a panoramic photo of ground school students at the University of Illinois taken August 16, 1917. I am grateful to Craig Parrish, a grandson of Albert Elliott Parrish, for the identification.

2 For information on Parrish’s family, I have consulted documents available at Ancestry.com as well as Boyd, The Parrish Family.

3 Commodore 1909, p. 53.

4 Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Albert E Parrish.

5 See “Parrish Wins.”

6 “Nashville Boy in Royal Flying Corps.”

7 See Foss’s list of “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers.

8 On the commander of 37 Squadron, see Leach’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card. On the squadron’s locations and planes, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, pp. 402–03. That B.E.2s were nevertheless still used by the pilots of No. 37 is apparent from the Goldhanger Flight Station 1917 – 1918 Operational Records that can be accessed via a link at “37-Squadron Night Landing Grounds.”

9 “Nashville Boy in Royal Flying Corps.” The plane was perhaps the second of two brought down one day, but others had been brought down on previous occasions.

10 “Air Training in England Exciting.”

11 “Nashville Boy in Royal Flying Corps.”

12 Cablegram 739-S.

13 Cablegram 1049-R, and McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

14 “Dr. Elebash Dies in Asheville, N.C.” War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Outgoing Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Casuals, on Aurania.

15 “Dr. Elebash Recuperating in English Hospital.”

16 “Nashville Tennis Star in Aviation.” The implied chronology here may be inaccurate; Parrish may have gone to Huntingdon (Wyton) after being commissioned. Confusion may have arisen due to the lapse of time between the recommendation and the confirmation, and between the latter and the time the commission became official.

17 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for June 16, 1918.

18 Rex calculated his accumulated solo hours at Marske as totalling 7 hours and 35 minutes, but it appears he shortchanged himself. When I add up his individual flight times, I get 9.5 hours.

19 Jeffords, Observers and Navigators, p. 369.

20 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for July 11, 1918.

21 [Biddle?], Special Orders No. 109.

22 “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 142.

23 It is conventional to designate the English plane a “DH.4” and the American a “DH-4.”

24 “8th Aero Squadron,” pp. 110-11.

25 “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 116; this is part of the “Report on Operations against the St. Mihiel Salient” submitted by Winant, which is also reproduced on pp. 689-91 of Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3.

26 Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p. 245.

27 “8th Aero Squadron,” pp. 111 and 112.

28 Ibid., p. 111.

29 Ibid., pp. 119–20.

30 Ibid., p. 120.

31 “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 135.

32 “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 112.

33 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 360.

34 “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 144.

35 “354th Aero Squadron (Observation),” p. 146.

36 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Albert Parrish.

37 “Lieut. Hobbs Has Very Famous Cane” and “Lieutenant Hobbs Arrives Tonight.”

38 Ancestry.com, 1930 United States Federal Census, record for Bert Parrish; 1940 United States Federal Census, record for Bert Parrish.