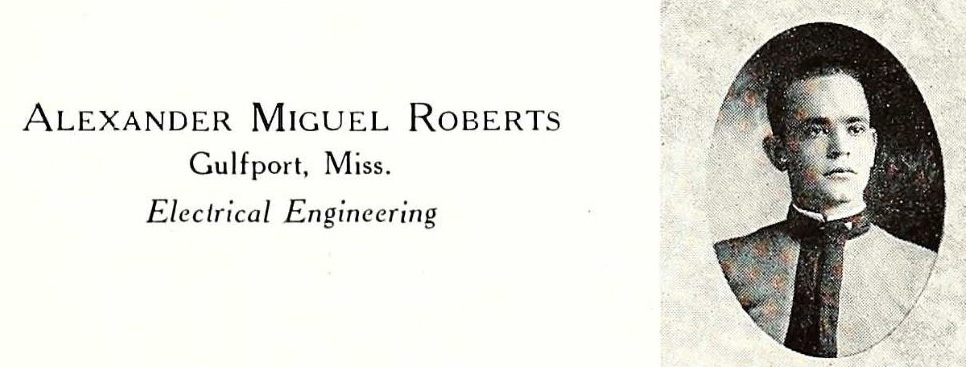

(Mexico City, Mexico, October 13, 1895–Tampa, Florida, July 23, 1988).1

Oxford & Grantham ✯ Thetford ✯ London Colney ✯ Turnberry ✯ France & No. 74 Sqn ✯ July 19, 1918 ✯ P.O.W. and afterwards ✯ Notes

Roberts was descended from Virginia-born Alexander Sanders Roberts of Delaware who fought in the Revolutionary War.2 The latter’s son, Robert Whyte Roberts, was born in Delaware but eventually settled in Mississippi; he served for a time as a Congressman from that state.3 Alexander Miguel Roberts’s paternal grandfather fought for the Confederacy; his son, Hiram Ridgway Taliaferro Roberts was born on the family’s Spring Hill Plantation near Hazlehurst, Mississippi, in 1861. After the war the family ran a hotel in Hazlehurst where Hiram R. T. Roberts, after graduating from the University of Mississippi, worked for a time. By the 1890s he was living in Mexico City and employed by the railroad. There he married Concepción Gálvez Sánchez, who was originally from Sahuayo, Michoacán.4 The couple’s three children were born in Mexico; the older daughter died in infancy; Alexander Miguel Roberts was the youngest child.5

The Roberts family kept up their connections in Mississippi, and Alexander Miguel Roberts returned there to study electrical engineering at the Agricultural and Mechanical College of the State of Mississippi near Starkville (now Mississippi State University).6

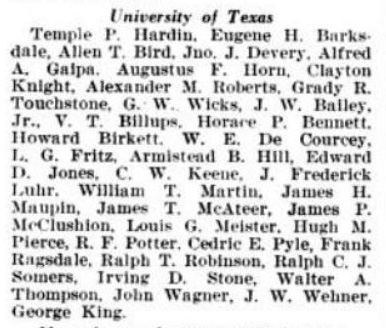

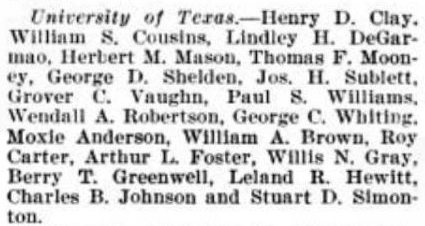

Both Roberts and fellow Mississippian Eugene Hoy Barksdale were in the class of 1918, but both left college in the spring of 1917 to volunteer for military service. When Roberts registered for the draft at the end of May 1917, he was at Fort Logan H. Roots in Arkansas, as was Barksdale. From there the two friends transferred to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and were assigned to the School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Texas at Austin, graduating from ground school there on August 25, 1917.7

Oxford & Grantham

Another disappointment was in store. The cadets, as they were now classed, would not immediately begin flying training but would instead attend ground school, again, at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford. The men spent their first night in England in various Oxford University colleges. The next morning, according to Barksdale’s diary entry, they “went over to Exeter College for permanent arrangements. 100 of our lot was thus sent to Christs [sic] Church College & the other 50 including A. M. Roberts & myself were sent to Queens College. We moved over then & Roberts & I drew a room for two but without a fire place. Here (at Queens) we found 40 other American aviators among whom were several whom I had known at Texas ground school. Our room adjoined a room in which were 5 other Americans & so we had a jolly good time.”9

Barksdale’s numbers are slightly off: other sources indicate that ninety men went Christ Church College with Elliott White Springs, while sixty of them, under first sergeant William Ludwig Deetjen, were assigned to The Queen’s College.10 At least six men who had graduated from the University of Texas S.M.A. on July 28, 1917, and who would have crossed paths with Barksdale and Roberts, were members of the first Oxford detachment, which had arrived at Oxford in early September 1917; many or all of them (there were fifty in the detachment) were housed in Queen’s.

The men of the second Oxford detachment, arriving in England and at Oxford on a Tuesday, had missed the start of the week’s classes and were not expected to begin work until the following Monday. They used their free time to explore Oxford and the surrounding countryside; there were dances and teas given where the Americans were welcomed. Initially the men could get late night passes for Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, but after two weeks such passes were restricted to Tuesday and Sunday. “Well,” writes Barkdale, “we were already dated up for the dance the following Sat. night [October 20, 1917] & when the time came & no passes could be gotten, my friend Roberts & I whispered to each other about slipping out & going anyway.” Barksdale ultimately decided not to risk it, but Roberts “collected up two other partners ([Donald Andrew] Wilson & [Donald Swett] Poler) to venture out with him and they went to see their fair dames.”

Unfortunately this was the evening the men of the first Oxford detachment staged a bibulous celebration of their exam results and their impending departure from Oxford, thereby greatly annoying the British authorities. “The C.O. [Bertram Richard White Beor, C.O. of the Oxford S.M.A.] and Major [Gerald Graham] Adeley [assistant C.O.] had been strolling around & ran up on some fellows drunk. They ask [sic] to see their passes & the boys ran. The C.O. thot these were American boys . . . (The three boys were afterward found out to be English cadets).”11

Deetjen recounts in his diary how “At 11:30 [p.m.] we were all formed, and rolls were called. ‘A’ Flight was present, I had 3 men absent in ‘B’ Flight. They were Wilson (room mate) Poler and Roberts.”12 It seems the three men had assumed they would not be missed and, rather than returning late after the dance, had put up at the Clarendon Hotel. They returned to Queen’s around 10 a.m. Sunday “to find they were caught. It was then I thot my pal Roberts was lost so far as I was concerned. They were then told to report to the Lieut. Colonel (C.O.) the next day to be court martialed.”13

Deetjen did his best to lose track of the names of the men who had missed roll call, and Geoffrey Dwyer, in charge of American flying training in England, did his best to defend Roberts, Poler, and Wilson to Adeley. Fortunately, when Deetjen took the three truants to Beor on Monday morning, the C.O. had calmed down. According to Barksdale, “About 11:00 A.M. Roberts came in classroom with a serious look on & I thot he was certainly sent to France but he was deceiving me by his look for the C.O. let them stay on provided they would not attempt such a thing again.”14 (All the men wanted to go to France as pilots, but not, as the threat is here, in disgrace to do menial tasks.) As a consequence of the Saturday night shenanigans, all the second Oxford detachment were ordered to move from Christ Church and Queen’s to the (even) less comfortable Exeter College.

Despite having to repeat material already covered in ground school in the U.S., the cadets came to appreciate being instructed by men who had war flying experience. They were also glad of the time allotted to exercise and sports. Towards the end of the month, Deetjen recounts how “We went out on the river today, and I stroked our crew of [Phillips Merrill] Payson, [Harry Adam] Schlotzhauer, [Joseph Frederick] Stillman & Roberts coxswain. We never knew when we left Exeter that we were in for a final race. Well we just naturally pulled the bottom out of the river and won by two boat lengths from Corpus Christi. We were given passes tonight as a reward.”

On the last day of October the detachment “recd orders that we would proceed to Grantham the following Saturday for machine gun course.”15 Twenty of the men, mainly ones who had had some flying experience already, were to go to Stamford for flying training, but there were simply not enough places at training squadrons for all of them. On November 2, 1917, they had “no classes of instruction but we had to hustle out and buy in a lot of bedding, other clothes etc.”; that evening, as a farewell to Oxford, Roberts and Barksdale went on a double date and had a “pleasant evening.”16

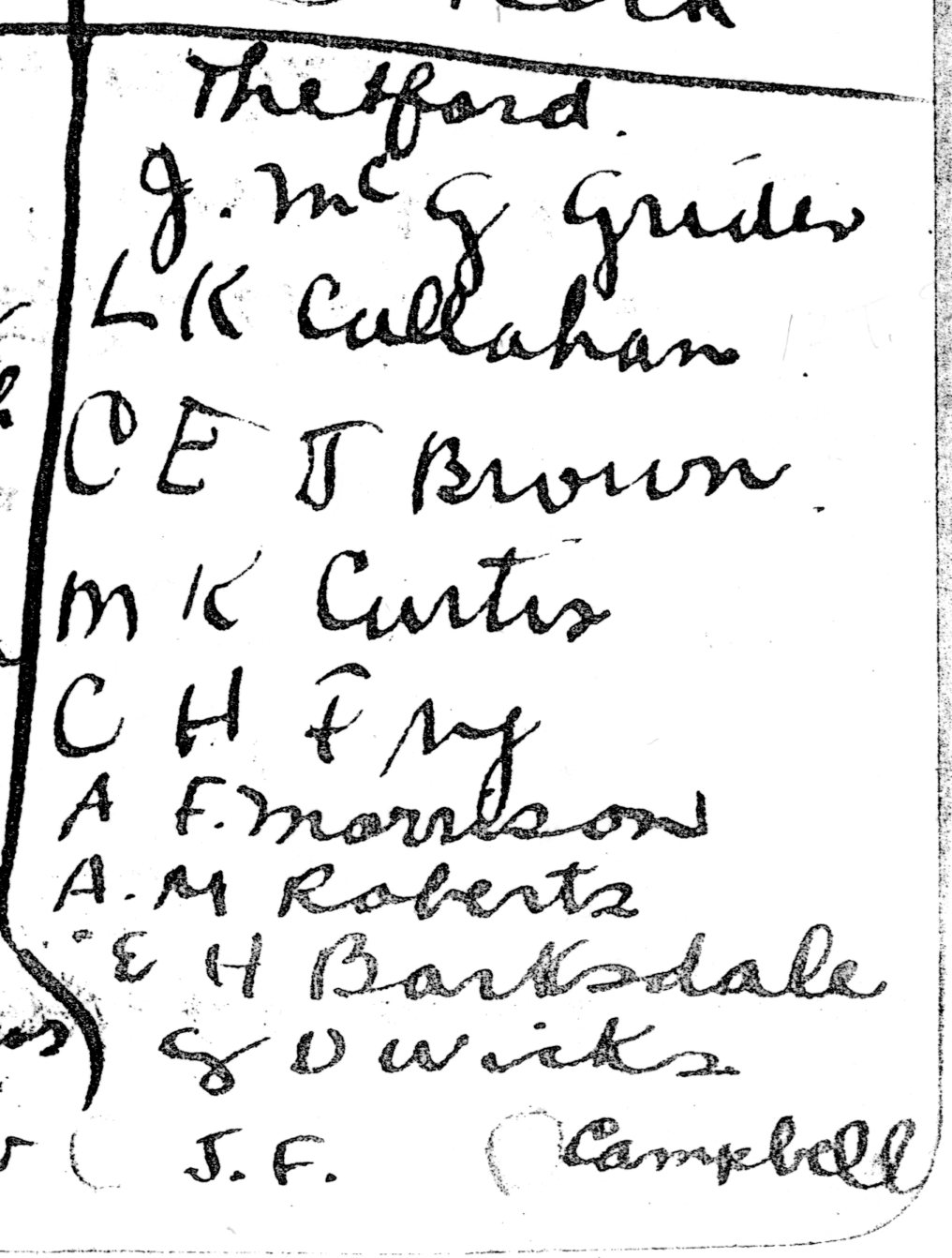

Setting out early on November 3, 1917, the men travelled by train to Grantham in Lincolnshire; Harrowby Camp and the machine gunnery school were located just northeast of the town. They were assigned to huts; Roberts was again with Barksdale in a hut with thirteen others. The assumption was that the men would spend two weeks learning about and practicing on the Vickers machine gun and then another two on the Lewis gun. Towards the end of the first course, however, they learned that fifty places had opened up at various training squadrons, and Roberts, along with Barksdale, was among the fifty men selected to fill them. The two of them were among the ten men posted to Nos. 12 and 25 Training Squadrons at Thetford in Norfolk.

Thetford

Jesse Frank Campbell, assigned to No. 25 T.S. with Roberts, Barksdale, Finley Austin Morrison, and Glenn Dickenson Wicks, recalled that they “Left Grantham at 8:30 for Thetford, missed connections at Petersboro [sic] and had to wait 4 hours. After changing again at Ely we finally got here at 3:00. Thetford is smaller than Grantham and seems just as dead. The flying field is 2 miles east of town.”17 Once arrived, according to Barksdale, “Were also assigned to room, Morrison, Wicks, Roberts & I being put together.”18

John McGavock Grider, who, with Charles Edward Brown, Laurence Kingsley Callahan, Marvin Kent Curtis, and Clarence Horne Fry, was assigned to No. 12 T.S. at Thetford, wrote the next day that “Thetford is not much; we have only “rumptys” Maurice Farman pushers and they are so unstable that they only fly when the air is smooth.”19 The Maurice Farman S.11 Shorthorn (“Rumpty”) had been developed before the war and used on the Western Front into 1915; they were ubiquitous at elementary training squadrons in late 1917. There was evidently a brief period of calm weather the day after the ten cadets arrived; both Barksdale and Grider note that Roberts got to fly.20 After that most days were too windy for flying, and it wasn’t until after Thanksgiving that things began to pick up some, although, Barksdale’s diary continues to record many days of “no flying” because of the weather.

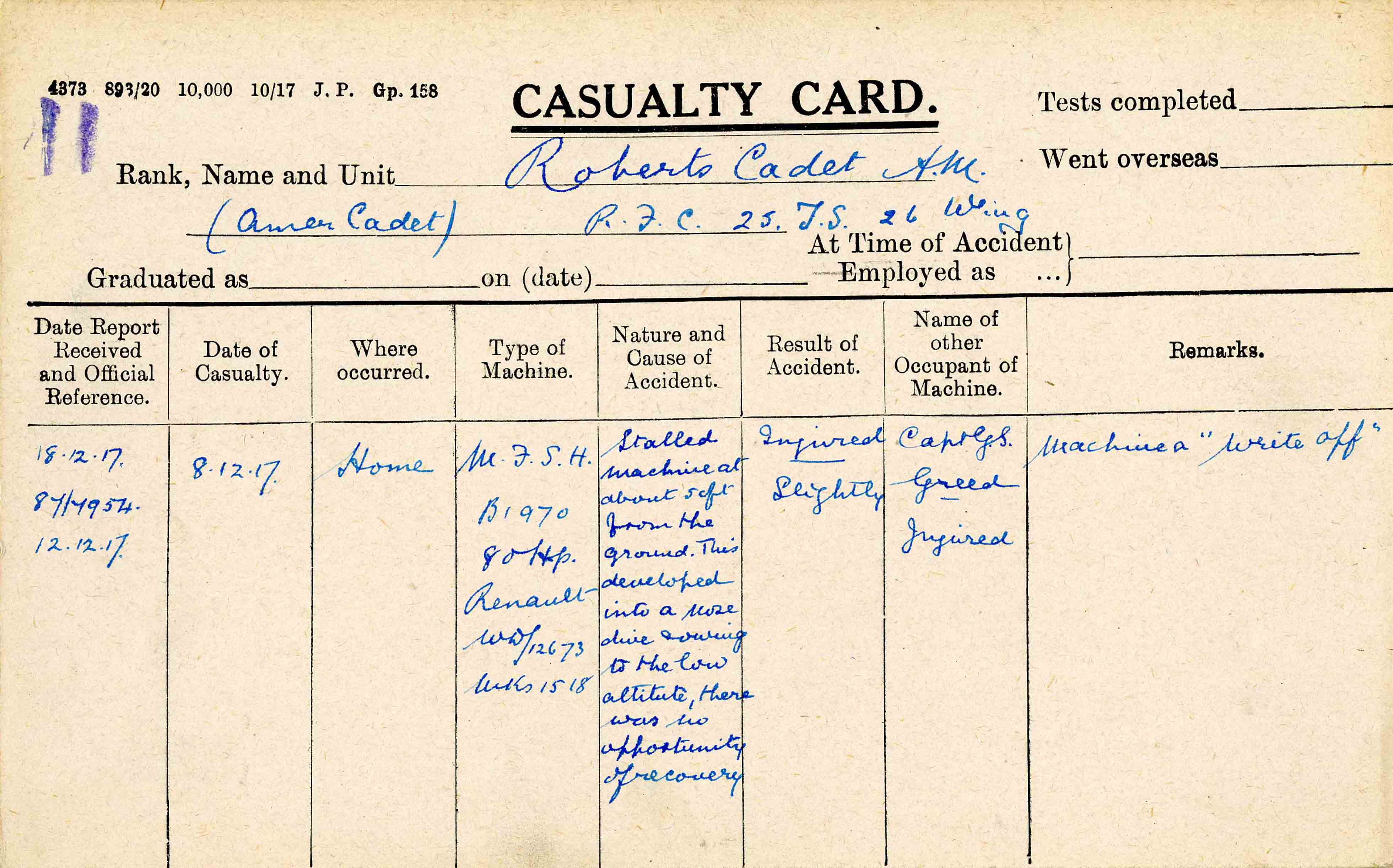

On the afternoon of December 8, 1917, Roberts went up with instructor Gordon Shergold Creed in Maurice Farman S.11 B1970.21 According to Barksdale,

Roberts 1st up & with Capt. Creed who had been drinking quite heavily tho we didn’t know it at the time. So just as soon as they got into the air Capt. Creed who was piloting began to do stunts about 40 feet in the air & on one of his steep banking turns the machine side slipped & started to spin, however they were so low to ground the machine only spun about ½ way round & crashed into a machine on the ground. I couldn’t see how either of them in the machine could remain alive in the great heap of broken up parts, but when I got there Roberts was being pulled out with only a bloody face & Capt. Creed with a broken leg & battered face. Fire broke out but was kept down. Both machines were crashed to pieces. . . . Roberts was well enough to be taken to our room by 6 A.M. but Capt. Creed was operated on that night & sent away to a special hospital.22

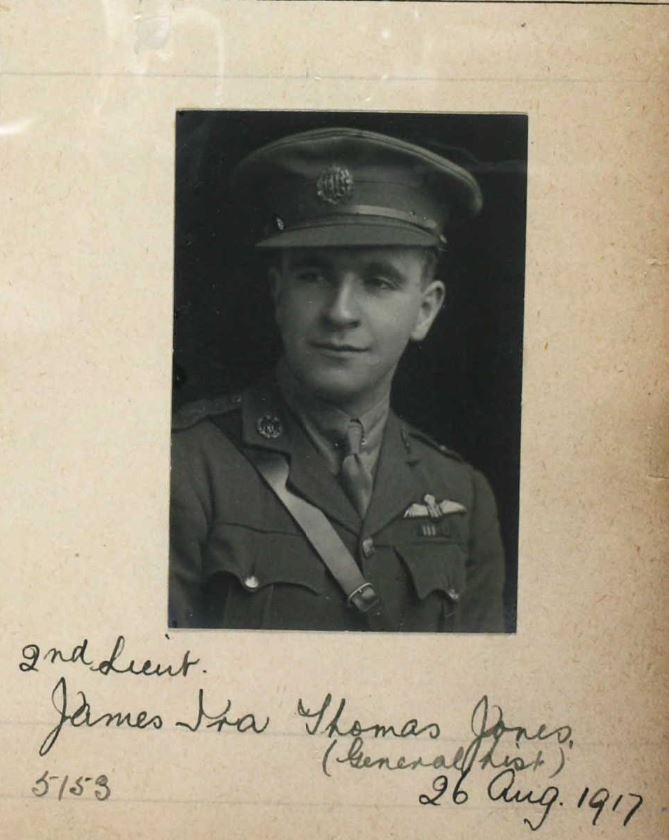

The next day Roberts was “feeling OK” and ready for an evening out in Thetford with Barksdale.23 He evidently soon finished up his dual flying. By Christmas Eve he had gotten in the four hours of solo flying required for graduation from an elementary training squadron and was posted to No. 74 T.S. at London Colney.24 Many years later James Ira Thomas “Taffy” Jones, also at No. 74 T.S., would recall that “Our school was lucky enough to get such grand types as Ken [sic] Curtis . . . , Fred Stillman, Alexander Roberts, H. G. Shoemaker, C. Matthiesssen, W. V. Waite [sic; sc. W. W. Wait] and A. F. Morrison.”25

London Colney

At London Colney, Roberts would join or soon be joined by all the men who had been at Thetford; three (Grider, Callahan, and Brown) were assigned to No. 56 T.S., and the rest, including Barksdale, to No. 74, across the field. Whether it was evident to them at this point is unknown, but all were on the path to becoming scout pilots rather than bomber or observation pilots.

The plane used for initial instruction at London Colney was the Avro, a dual-control two-seater specifically designed for pilot training. Winter weather and a limited number of planes meant that Roberts and his fellow cadets did not get nearly as many hours in the air as they would have liked—a situation exacerbated by, in Jones’s words, “The keenness of these warriors to go solo as soon as possible [which] resulted in many accidents”; the frequent entries in Barksdale’s diary that mention crashes attest to this. It was thus not until January 21, 1918, that Roberts flew solo, “he being the 1st American in 74th T.S. to get on solo on Avro machine.”26

Roberts was evidently very determined or lucky, or both. Despite their similar situations, he continued ahead of Barksdale in training progress. In mid February he “did his cross country flight & just got back before dark.”27 The cross country flight—“usually from London Colney to Northolt and Hounslow and back to the aerodrome”28— was one of several tests that cadets needed to pass in order to graduate from this stage of their R.F.C. training. The next day, February 17, 1918, Barksdale notes that Roberts “had his first flip on a Soph. [sic] Pup & completed his test for his commission.”

It is not evident what the test for his commission was—the general understanding was that the basic requirement was twenty hours solo flying,29 four of which Roberts would have had under his belt at the end of his time at Thetford, and he presumably gained the next sixteen in Avros at No. 74 T.S. His having flown a Sopwith Pup, a service machine, probably meant he had also just completed the final requirement for graduation from this intermediate stage of his R.F.C. training. In any case, a recommendation for his commission was evidently forwarded around this time to A.E.F. H.Q., and, with military speed, Pershing sent it on to Washington in a cable dated February 28, 1918. The cable approving the recommendation is dated March 10, 1918, and, finally, on March 19, 1918, Barksdale noted in his diary “Roberts called to London to receive his commission today.” Of the group of ten who had been sent together to Thetford, Roberts was the first to become a first lieutenant.

The preceding day, March 18, 1918, Barksdale noted in his diary that “Roberts took his first flip on a Spad. Did well.” This latter accomplishment presumably took place at No. 56 T.S. At the beginning of March, No. 74 T.S. had turned into an operational squadron preparing to depart for France, and its American students had been transferred across the field at London Colney to No. 56.30 Shortly after the move, Roberts had several days leave; Barksdale indicates Roberts returned to London Colney on March 14, 1918. Over the course of his remaining time at London Colney Roberts would have become familiar and with and flown the S.E.5, the plane he would later fly operationally.

Turnberry

From London Colney Roberts was posted to the School of Aerial Gunnery at Turnberry (on the west coast of Scotland, about forty miles southwest of Glasgow). I cannot find documentation of the date of his posting, but it is possible that he went straight up to Scotland after receiving his commission in London; there are no mentions of him at London Colney after March 19, 1918, in Barksdale’s diary. At Turnberry Roberts would have stayed in what in peacetime was the Turnberry golf course hotel—unexpectedly luxurious accommodations much enjoyed by the student pilots. From Turnberry he would have gone up the coast to Ayr, to the School of Aerial Fighting, where he would have—assuming his training resembled that of, for example, Parr Hooper, who was there at about the same time—put in many hours on Avros and Spads, but also S.E.5s, practicing stunting, formation flying, and fighting.

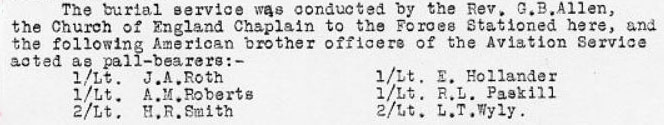

While he was still at Turnberry, Roberts wrote to Barksdale, “telling of Beader [sic] being burned up in an SE5.”31 Their fellow second Oxford detachment member George Atherton Brader was killed on April 5, 1918, when his plane spun into the ground and caught fire. Just over six weeks later, Roberts served as a pall bearer at the funeral of George Clarke Squires, an American killed when his Sopwith Camel crashed on May 18, 1918, at Turnberry.32

Roberts may have remained in Scotland until he was posted overseas in early June 1918, or he may, like many of his fellow second Oxford detachment members have spent some time as a ferry pilot.

France and No. 74 Squadron R.A.F.

On June 7, 1918, Barksdale noted in his diary that he “rec’d telegram from Roberts yesterday saying he had been ordered overseas.” Roberts’s casualty form, a record of active service postings, puts him at “No. 2 ASD” on June 9, 1918, i.e., at the pilots pool of No. 2 Aeroplane Supply Depot at Rang du Fliers, near Boulogne.33 There are photos taken by John Chadbourn Rorison of men at 2 A.S.D. around this time that include Roberts.34 After a week of digging trenches and otherwise filling in time, Roberts was posted on June 17, 1918, to No. 74 Squadron35 —he was back with many of the men he had known at London Colney. Jones recorded under that date that “Alexander Roberts, one of the Americans who trained with me at London Colney, has come to join us. Like most of the other Yanks, he is a fine fellow who should be an acquisition to the Squadron.”36

No. 74 Squadron flew S.E.5a’s and was stationed at Clairmarais Nord. Commanded by Keith Logan “Grid” Caldwell, No. 74 was part of the R.A.F. 11th (Army) Wing, II Brigade, attached to the British Second Army. The Second Army front ran approximately from Houthulst Forest south past Ypres to Nieppe Forest.37 From the Clairmarais aerodrome the pilots of No. 74 Squadron flew line and offensive patrols as well as, occasionally, escort, ground strafing, and wireless interception missions, all the while seeking to put enemy reconnaissance planes out of commission and to eliminate enemy scouts flying over and east of the Second Army front north and south of Ypres—all this is apparent from the account of No. 74 Squadron provided by Ira Jones in Tiger Squadron. As with a number of other squadrons, the squadron record book and other relevant original documents appear not to have survived, so Roberts’s activities must be pieced together from the accounts of his fellow pilots and other documents.

Jones, who commanded A flight, noted that Roberts was assigned to C flight.38 According to some accounts, men new to an R.A.F. squadron had two weeks of orientation before they were permitted to go over the lines. It may have been Jones’s previous acquaintance with Roberts that prompted him to bend the rules. On June 25, 1918, eight days after Roberts’s arrival at 74, Jones recorded that “Just after eleven I decided to go up and wage a private war. Battell [sic; sc. Andrew John Battel], Roberts and Swazi [Percy Frank Charles Howe] volunteered to come with me, so I took them. Placing Roberts nearest to me on my right, as he was a new hand, Battell on my left, with Swazi behind Roberts, we left the ground in formation, climbing steadily at 65 m.p.h., heading for Ypres.” Well before Jones got involved in what he characterized as a “great scrap,” “Roberts’s engine gave trouble. He fired a green light, the signal that he was returning home.” Jones was perhaps regretting having allowed this new pilot on this mission: “I was really relieved. I could see several birds in the distance that looked very much like Hun species to me, and this was going to be his first offensive patrol.”39

Absent the squadron record book, it is not possible to say how many missions Roberts successfully took part in—it is mainly the problem flights that have left records. But it is worth noting that towards the end of June 1918 a number of the pilots of No. 74 Squadron, including Squadron C.O. Caldwell, had come down with influenza, placing an added burden on those who were well; Roberts probably got in a good deal of operational flying. And he seems to have been well thought of: apropos of a patrol on July 15, 1918 (of which more below), Jones notes that “[Frederick John] Hunt and Roberts are our latest recruits for these private battles.”40

On July 6, 1918, Roberts flew S.E.5a C8845 on a “special mission.” On landing “Tail skid buried itself in deep furrow and broke longeron”—Roberts was not hurt, but the plane was damaged to the point that it was “NWR” (not worth repairing).41 The next day he was slightly injured when he had to make a forced landing in S.E.5a C1779, the engine having failed during an operational patrol. The damage to the plane was enough to warrant its being struck off charge, and the incident memorable enough that Roberts wrote to Barksdale about it.42 The next day, July 8, 1918, Roberts had the opportunity to catch up on news of old friends from the second Oxford detachment when Curtis, now at the 148th Aero, visited No. 74 Squadron.43

On the evidence of Leonard Atwood Richardson’s log book and diary entries, No. 74 Squadron continued flying missions daily, with the exception of July 12, 1918, and perhaps July 17, 1918.44 Some of these were, if I understand Richardson’s accounts correctly, line patrols, but also some offensive patrols to Roulers and back, and on several occasions enemy airplanes were engaged.

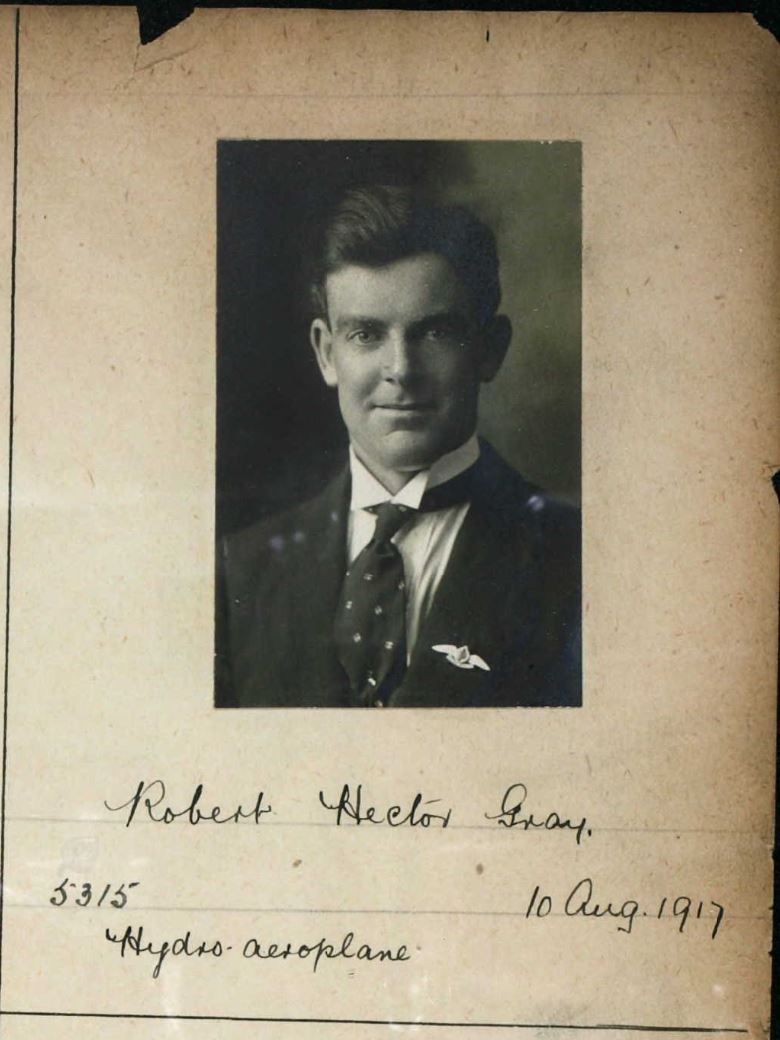

Jones wrote an extensive account on one such patrol that took place on July 15, 1918; Roberts, Richardson, Gray, and Howe were among those who participated. Squadron C.O. Caldwell had just returned after a week away with influenza: “Grid celebrated his return by leading a typical ‘Caldwell’ squadron patrol at breakfast hour. As usual, he totally disregarded tactics. Crossing the line at Ypres at 12,000 feet, he made straight for Roulers Aerodrome. Here he circled around until a large formation of Huns arrived from above to accept his challenge. Then an unholy dog fight started.” Early on, Gray was seen to “go spinning down with a cloud of Fokkers on his tail.” Jones attacked “an all-black Fokker. . . . Round and round, faster and faster we went, neither able to get a shot at the other. Another Hun got on my tail, Roberts joined on to his, and another Hun swung in behind him.”45 Caldwell shot down a plane, and soon after that, the fighting ended. When the pilots arrived back at Clairmarais, they realized that, in addition to having lost Gray, Howe was missing; he had crashed in allied territory and was at a field hospital.

According to Jones, “nothing of interest” occurred over the next three days, but Richardson’s log book and diary suggest otherwise, at least with respect to June 16, 1918. Having already flown two missions (showing a newly-arrived American, Harold Goodman Shoemaker, the lines on one of them), Richardson went up a third time at 7 p.m.: “In eve we do a squadron show”—this, and Richardson’s references to C flight suggest that Roberts participated. “We meet Huns over Roulers. It’s a wonder any of us got home. Grid attacked an enemy formation with our lower flight and did not see those above. While ‘C’ flight was upstairs getting ready to dive down into the scrap we see another large enemy formation coming in from above.” As the squadron headed back towards the lines, they spotted a third enemy formation that did not attack. Richardson noted in his log book: “millions of enemy aircraft—funny fight.” The next two days were less eventful.

July 19, 1918

On July 19, 1918, B and C flights did what Jones called “a breakfast offensive patrol.” According to Richardson, they set off at 8 a.m., tasked with escorting Bristol Fighters from No. 20 Squadron R.A.F. on their way to and from bombing either Roulers (Richardson) or Cortrai (Jones).46 The Bristol Fighters and S.E.5a’s reached their objective and the bombs were dropped. As they began heading back towards the lines, “they found a large formation of Fokker biplanes and triplanes and Pfalz Scouts ready to attack.”47 “[W]e got into a real sized dog-fight.”48

Richardson dove on an enemy plane “until he went down. I was so intent on watching, trying to get a true confirmation, that I forgot my tail, so when I zoomed up to maintain altitude, I was very much surprised to receive a cockpit full of bullets.”49 Richardson managed to crash land inside Allied lines and was taken to a field hospital. Roberts, flying S.E.5a E5948, made the same error as Richardson. According to Jones, “Roberts was seen to pounce on a Fokker biplane, shoot it up good and hearty, then follow it down beneath the general engagement. Fatal. He was pounced upon by a biplane and a triplane. When last seen, he was fighting for dear life.”50 According to one account, the triplane that attacked Roberts was the one that “had apparently spun down . . . under attack from . . . Richards [sic; sc. Richardson].”51

Roberts was debriefed after the war, and his interlocutor recorded him stating that he “attacked a two seater and while observing the effect of his fire was set upon by a Fokker biplane and a triplane. A machine gun burst penetrated the lower left wing and another crashed through the instrument board of the motor tearing his sleeve. With engine trouble he was forced to a landing in a shell hole. He was ten kilometers behind the lines near Moslede [sic; sc. Moorslede].”52

Unusually, there is a description of this encounter by the pilot credited with shooting Roberts down. Josef Carl Peter Jacobs, the commanding officer of Jagdstaffel 7, stationed at Sainte Marguerite at this time, kept a diary that includes an entry for July 19, 1918. His account suggests that it might not have mattered that Roberts was distracted as he attempted to follow or observe the plane he had attacked.

Jacobs and his flight, flying Fokker Dr1 triplanes, set out very early the morning of July 19, 1918, hoping “to chase away the enemy aircraft who disturbed us in our sleep every morning with their bombs.” They returned after an uneventful mission and then set out again. Heading towards the front

I saw through a light haze two-seaters and single-seaters coming from Bailleul just below the clouds hardly more than 1500m altitude . . . a flight of SEs came out of the clouds down on me firing furiously. Right away I turned toward one SE but was then attacked from behind by three of them. At the same time I also saw three Bristol Fighters shooting as they passed me so I dived. In the meantime a second SE formation came to their assistance as did two German Jastas. All engaged in the whirlwind battle. One moment I held this enemy in my sight, the next moment shook that enemy from my body without being able to shoot properly myself. Suddenly I watched another opponent going after a Fokker, I fired, the Englishman gave up. A second one came to his aid and quickly I had him wrapped up and did not let him loose. I followed him always at 50 metres and when he wanted to straighten out I shot him full of holes so that he turned toward Germany and prepared to land. He glided very slowly across a road, pulled up a little and then turned over on its head. He jumped out immediately and ran to a deserted trench followed by some soldiers.53

Jacobs goes on to tell how “When I came home I at once took my car and drove to the landing site. It was a brand new SE5a with an American 1st Lieutenant as pilot who however had already been returned. His name was A. M. Roberts . . . As a person he was very nice. . . .” In his debriefing Roberts does not mention meeting Jacobs, but in a letter to his father wrote that “On the 19th I was shot down by a German ace, I being his 24th victory. He talked with me for a long while and said he was glad that I was not killed and promised to write to you.”54

P.O.W. and afterwards

In this same letter Roberts mentions that “I am with a New Zealand friend who was captured a few days ago”—this would be Gray, shot down on July 15, 1918. The newspaper article that quotes from Roberts’s letter states that he was at a P.O.W. camp in Limburg-an-der-Lahn. Apparently prior to arriving at Limburg, Roberts attempted to escape by jumping from a train between Liège and Aachen and heading for the Dutch border; he was recaptured. At some point, according to his debriefing document, he passed through a prison camp at Cortrai.

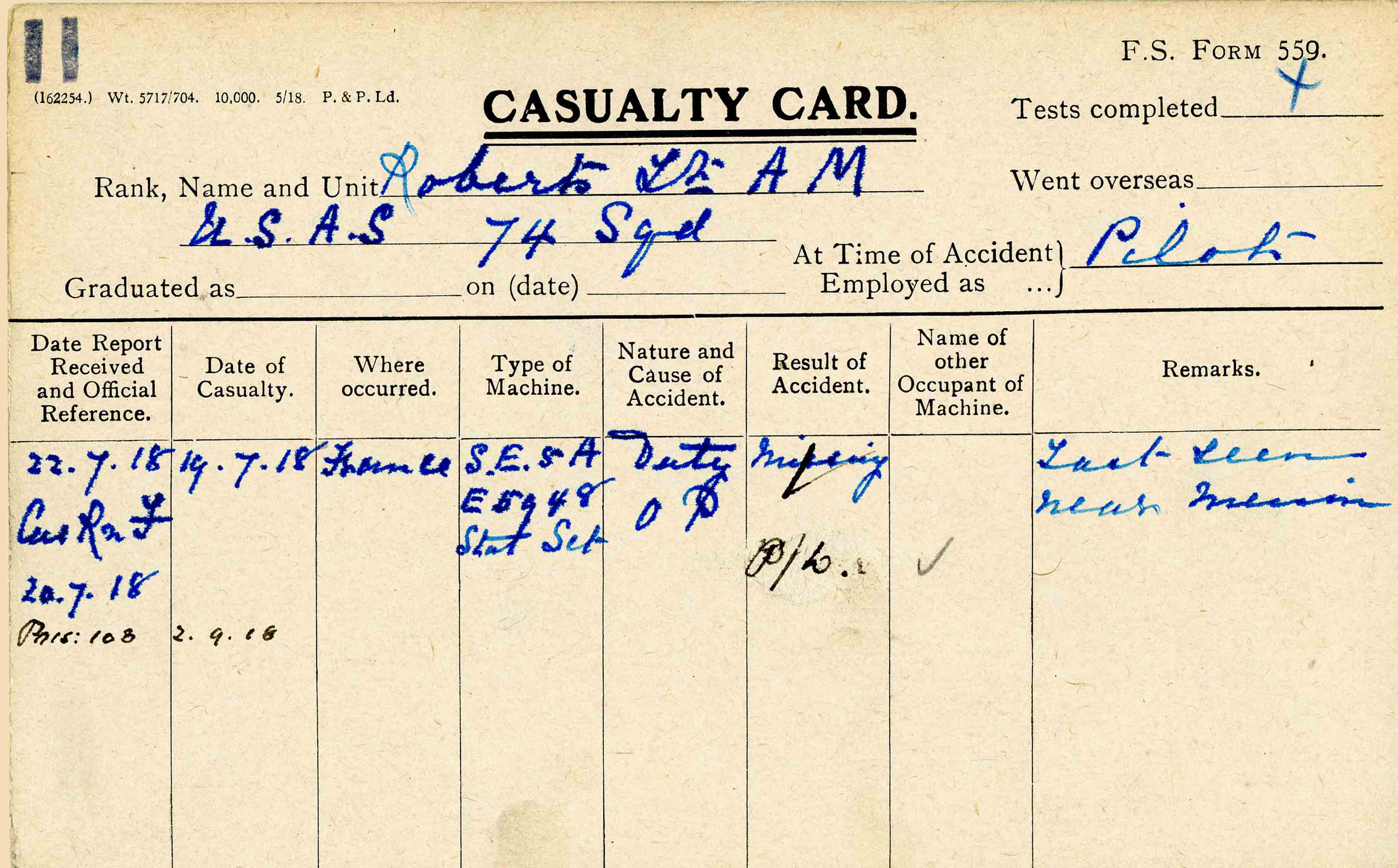

For some time Roberts’s fate was unknown to his squadron and his family, and the worst was assumed. The relevant casualty card describes him as missing and “Last seen near Menin.”55

Barksdale, at Rang du Fliers waiting to be posted to a squadron, wrote in his diary on July 30, 1918, that “Late in evening a Corporal from 74th Squadron came over in a tender for a fellow & told me that Alex. M. Roberts went down in flames over Hunland. . . . Tis the worst news that [I] have ever recd in my life.” Two weeks later, Barksdale was able to visit No. 74 Squadron and learned that “Alex. Roberts has lots of chances of merely being a prisoner & not hurt at all.” Then on August 18, 1918, “Recd word today that Alex. Roberts is a prisoner in German and unhurt. O joy & thank goodness for that.” Two days later, the news that Roberts was a P.O.W. in an unknown camp appeared in U.S. papers, and towards the end of August 1918, it was learned that he was at Rastatt in Baden.56

Roberts had apparently been at Rastatt since at least early August. In his debriefing he described having escaped, along with Gray, from the Friedrichsfeste prison camp there on August 5, 1918 (or August 6, 1918; the account is unclear). They presumably used the conveniently removable bars in one of the prison’s second story windows. According to Dwight R. Messimer “sixty three men escaped through that window from 1915 to 1918.”57 However, “everyone who got out of Friedrichsfeste was brought back.”58 Roberts and Gray’s experience was apparently typical. They “spent seven days in the Black Forest but gave it up as they had no food and Lieutenant Robert’s [sic] had sore feet, which made walking almost impossible. They were returned to a jail, Fremdenstatt, formerly the estate of some prominent German, where they were treated rather well.”59 I have not been able to identify the jail, unless this is a muddled reference to Trausnitz Castle in Landshut, Bavaria, where Roberts is known to have been held. A photo of prisoners of war taken in the latter part of September 1918 at Landshut includes Roberts standing next to fellow second Oxford detachment member Horace Palmer Wells, who had been captured while flying for No. 104 Squadron I.A.F.60

According to a brief account written by Curtis (who had trained at Thetford and London Colney with Roberts), he and Roberts were among twenty prisoners transferred on October 24, 1918, from Landshut to the P.O.W. camp at Villingen in the Black Forest, about sixty miles south of Rastatt: “On Oct. 24 twenty of us rose at 3:30 A.M., breakfasted and descended to the station and departed before light. That night we came to Ulm and were fed in the station and marched through town to a prison for the night. Off before light in the morning in a boxcar for two hours, then in a 3rd class coach, food at Immendingen, and landed at Villingen about 3:30 P.M. and marched to the lager. [Johnson Darby] Kenyon and I went into the mess with A. M. Roberts, Horace Wells, and [Harold Archibald] MacChesney. The twenty of us are rooming in a big barrack with two stoves.”61

Wells recalled that “We celebrated the armistice at Villigen [sic] and came back with the first trainload of repatriated officers from Germany.”62 Wells, Roberts, and a number of others made their way back to England and were at an embarkation camp at Liverpool by January 7, 1919. From there they sailed to Brest, France, from which port they sailed on January 10, 1919, arriving at Boston on January 21, 1919. Shipmates included Edward Carter Braxton Landon and Charles Carvel Fleet of the second Oxford detachment, as well as Kenyon and several others who had been P.O.W.s.63

Roberts’s parents were now residing in Cuba where his father had established the Roberts Tobacco Company in 1918; Roberts made his way there rather than to Gulfport.64 Roberts spent a number of years in Havana running Roberts Tobacco and expanding into other businesses. He once again served in the army during World War II, moving from Havana to Miami Beach in 1943 and eventually settling in Tampa.65

mrsmcq March 17, 2023

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Roberts’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Alexander Miguel Roberts. His place and date of death are taken from “Funeral Notices,” The Tampa Tribune. The photo is cropped from a formal full-length portrait that was handed down in Roberts’s family. I am grateful to Carlos Pérez Osorio, Roberts’s great-nephew, for permission to use the photo.

2 See Fair, Roach, Roberts, Ridgeway, and Allied Families, pp. 96–97.

3 Ibid.

4 Unfortunately I have not been able to trace her background with any certainty due to my rudimentary Spanish and inadequate genealogy skills when it comes to Mexican families.

5 On Roberts’s family, see documents available at Ancestry.com.

6 The Reveille, p. 115.

7 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

8 Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918.” Various explanations have been offered for the change of plans; see, for example, those supplied by Hamilton Hadley on p. 4 (286) of his “Foreign Aviation Detachments,” by Geoffrey Dwyer on p. 2 of his “Report on Air Service Flying Training Department in England,” and by Claude E. Duncan as recorded in Sloan and Hocutt, “The Real Italian Detachment,” p. 44.

9 I should note that I cannot tell whether errors in spelling and dating are in Barksdale’s original diary or have been introduced in the transcription.

10 See, for example, Deetjen’s diary entry for October 4, 1917.

11 Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry dated October 8, 1917 (which covers events of the 8th and subsequent days). This is one of several accounts of the evening; see, for example, the entry for October 22, 1917, in War Birds.

12 Deetjen, diary entry for October 21, 1917.

13 Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry for October 8, 1917.

14 Ibid., entry for October 20, 1917.

15 Ibid., entry for October 31, 1917.

16 Ibid., entry for November 2, 1917.

17 Jesse Campbell, diary entry dated November 18, 1917. This entry should almost certainly be dated November 19, 1918.

18 Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry for November 18, 1917. Like Jesse Campbell, Barksdale seems to have misdated this entry; it should be November 19, 1917.

19 [Grider], diary October 3, 1917 – February 7, 1918, entry for November 20, 1917. (NB: I have added punctuation.)

20 Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry for November 19, 1917 (sc. November 20, 1917); [Grider], diary October 3, 1917 – February 7, 1918, entry for November 20, 1917.

21 “Roberts, A.M.” The pilot’s last name is given on this casualty card as “Greed,” and the associated casualty card for Creed has also been filled in and filed under that incorrect spelling.

22 Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry for December 8, 1917.

23 Ibid., entry for December 9, 1917.

24 Ibid., entry for December 24, 1917. Both Grider (at Thetford), diary entry for January 1, 1918, and Read (at Wyton), letter of December 19, 1917, record four hours solo as the prerequisite for graduation; Jones (at Northolt), Tiger Squadron, p. 56, mentions five.

25 Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 60.

26 Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry for January 21, 1918.

27 Ibid., entry for January 16, 1918. Jesse Campbell’s diary entry for January 17, 1918, states that “Morrison, Matheson, and Roberts did their cross country this afternoon and came back in fog.” There are problems with dates in both diaries, so that, in the absence of Roberts’s log book, it is not possible to say which date is correct.

28 Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 61.

29 See, for example, Hooper, Somewhere in France, letters of December 28, 1917, and January 31 and February 14, 1918; Deetjen, diary entries for February 14 and 23, 1918; and Milnor, diary entry for January 16, 1918.

30 The 74 Squadron Orderly room record book shows Barksdale transferred to No. 56 T.S. on March 5, 1918; Roberts on March 8, 1918.

31 Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry for April 8, 1918.

32 Rees, letter to Mrs. George C. Squires.

33 “Lieut. A. M Roberts U. S. A. S.”

34 See Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 43; photo 04OAS-B39-F02-PB051 in the Ola A. Sater Collection at the University of Texas at Dallas is another group photo of men at Rang du Fliers that includes Roberts.

35 “Lieut. A. M Roberts U. S. A. S.”

36 Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 139.

37 This is the description of the Second Army front in the late spring and summer of 1918 provided by Blanford, “Sans Escort,” part 1, p. 147.

38 Jones, Tiger Squadron, pp. 142, 139.

39 Ibid., p. 145.

40 Ibid., p. 149. Hunt’s casualty form (“2nd Lieut. F.J Hunt”) indicates he was not posted to 74 Squadron until July 21, 1918; Jones appears to have collapsed recollections from several days into one account.

41 Information taken from Pentland, Royal Flying Corps. Pentland’s source is one of the “reports on aeroplane and personnel casualties” included in Air 1/857 at The National Archives (UK).

42 Pentland, Royal Flying Corps (based on Air 1/857; see preceding note); Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry for July 19, 1918.

43 Richardson, Pilot’s Log, p. 213 (diary entry for July 8, 1918).

44 See Richardson, Pilot’s Log, for those dates.

45 Jones, Tiger Squadron, pp. 149; cf. Richardson, Pilot’s Log, pp. 215–16.

46 Richardson, Pilot’s Log, p. 217; Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 150.

47 Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 150.

48 Richardson, Pilot’s Log, pp. 217–18.

49 Ibid. p. 218.

50 Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 150.

51 Sellwood, Winged Sabres, Chapter 22.

52 Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany, p. 264. See GregVan’s contribution to “Somebody from Mexico in the 17th Aero Squadron” for an image of the downed plane.

53 Lawson, “Jasta 7 under ‘Kobes’,” part 2, p. 119. On p. 131, Lawson indicates that the original diary was in the possession of James J. Parks; I have not thus far (March 10, 2023) been able to consult it to check the translation, which seems occasionally unclear and awkward.

54 “Roberts Thinks He Got 1 Machine.”

55 “Roberts, A.M.”

56 “Gulfport Youth in German Prison”; “Americans Held in German Prison Camps.”

57 Messimer, Escape from Villingen, 1918, p. 53.

58 Ibid, p. 55.

59 Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany, p. 264.

60 A copy of the photo appears after p. 131 of Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany; p. 131 provides the location and identifications. A copy was also kept by Zenos Ramsey Miller, who arrived at Landshut on September 21, 1918, and appears in the photo. See Miller, Autograph Book and Diary of Zenos R. Miller (Diary 1), p. 49. A further copy was kept by George Wright Puryear; see “American Prisoners of War at Burg Trausnitz, Landshut, Germany” at Puryear Family Photograph Albums, 1890-1945.

61 Curtis, Notebook kept while a prisoner of war. Some portions of the text are unreadable in the image I am working with; I have reconstructed it as best I can.

62 Wells, “An Interview with Horace P. Wells,” p. 90.

63 War Department. Office of the Quartermaster General. Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for detachment of casual officers on Canada, departing Brest January 10, 1919.

64 “Alexander M. Roberts Reaches America.”

65 “Army Family Arrives Here”; “Funeral Notices,” The Tampa Tribune.