(Mandan, North Dakota, August 5, 1894 – Irvine, California, January 23, 1989).1

Training in England ✯ Flying with No. 55 Squadron R.A.F. ✯ Leading the 11th Aero

Heater’s father, John Riley Heater, worked as a railway conductor; Heater’s Glasgow-born mother, Jane “Jennie” Heater, née Neil, emigrated with her family from Scotland in the 1880s.2 Heater planned a military career after he graduated from high school in Mandan (on the west bank of the Missouri River, across from Bismarck) in 1912. He had a choice of West Point or Annapolis; he chose the former.3 Just a few weeks after he entered the Academy in the summer of 1913, however, a severe ankle injury forced him to resign.4

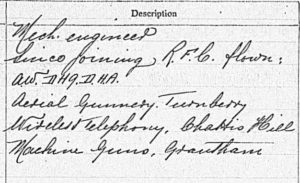

He enrolled at Purdue University, where he studied mechanical engineering, graduating in 1917.5 When he registered for the draft at the end of May of that year, he was employed by Western Union in Buffalo, New York. From there he went to Ithaca, New York, where he was a member of the Cornell University School of Military Aeronautics ground school class that graduated September 1, 1917.6

Along with most of his ground school classmates, Heater chose or was chosen to continue his training in Italy. He was thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who departed New York on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania. After a stopover at Halifax to join a convoy, the Carmania set out across the Atlantic on September 21, 1917. The men, who travelled first class, were assigned to state rooms alphabetically, and one of Heater’s roommates was Parr Hooper. Hooper was happy to discover that they were both members of the same Tau Beta Pi engineering honor society; the two of them shared a dislike of the Italian languages classes conducted on board by Fiorello La Guardia.7 About halfway through the crossing the men began taking shifts in around-the-clock submarine watch. On at least one occasion, Heater and Hooper shared duty and “had the station on the starboard end of the navigating bridge. One of us combed the sea with glasses and the other one with the naked eyes, and alternated about every 10 minutes. . . . We wagered a dinner in Rome for the one who saw the enemy first, but it was never decided.”8 This was fortunate for many reasons, including that they never went to Italy.

Once arrived at Liverpool October 2, 1917, the men “were told that we were going to stay and get our flying training with the Royal Air Force. 150 spoiled brats finally had to be subdued by an American Major Biddle who offered the choice of our cooperation or quick trials for mutiny. We quieted down and soon were again going through ground school with its endless hours of Morse code and machine gun familiarization. We didn’t know we had had a most fortunate change, for Italy was a bad nightmare. . . .”9 The men still jokingly referred to themselves as the “Italian detachment,” but at some point came to be known as the “second Oxford detachment,” as distinct from the “first Oxford detachment,” fifty men who, under similar circumstances, had arrived in England September 2, 1917, and had also been put through a repeat course of ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University.

When Heater wrote home from Oxford on October 3, 1917, he had just learned that “we’ll be here about six weeks,” but it turned out to be just over four.9a The vast majority of the cadets, including Heater, set off from Oxford on November 3, 1917, for Harrowby Camp, a machine gun training center at Grantham in Lincolnshire, “where we again went through machine guns from piece by piece blindfolded to ground firing by the hour.”10 Fifty of the men left Grantham for training squadrons after about two weeks, but, again, Heater was among the majority who had to wait yet a bit longer before being assigned to squadrons. Finally, on December 3, 1917, the Monday after Thanksgiving—which had been declared a camp holiday and celebrated in great style—the men still at Grantham were posted to “any spot that could accommodate a few stray cadets.”11

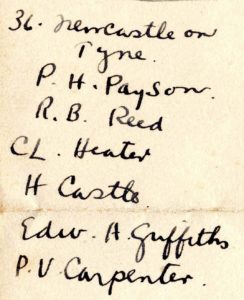

Heater, along with Paul Vincent Carpenter, Harvard DeHart Castle, Edward Addison Griffiths, Phillips Merrill Payson, and Richard Brumback Reed, was assigned to No. 36 Squadron, a home defense squadron flying F.E.2b’s and F.E.2d’s, based in and around Newcastle.12 Heater “and my roommate since Cornell [Reed] landed at a night flying detachment of six or eight officers at a very small field near the North Sea coast entitled Hylton, near Sunderland.”13 While most of the men assigned to other squadrons actually began training, Heater and his fellow detachment members found that at 36 “There was little flying activity . . . although we got a couple of short rides in the F.E.2b early British machines. . . . No instruction was given us.”14 This account is corroborated by Castle, who “said their crowd had had no instruction thus far; they were just marking time and fed up.”15 A brief distraction was provided after a couple of weeks when “we had a pass for London where on Christmas we were guests for dinner at the Royal Automobile Club, with a small party and the Marchioness of Tweesdale [sic], an amiable dowager, ‘doing her part’.”15a

Sometime early in the new year, Heater was posted to No. 6 Training Depot Station at Boscombe Down, about ten miles north of Salisbury. Instructional planes there included DH.6s , Avros, and B.E.2c’s and B.E.2e’s (the last three once operational two-seater aircraft now obsolete and used for training).16 According to his own account, Heater began training on DH.6s—a plane designed as a trainer for pilots destined for observation or bombing, and a “sign that we would not be trained for the more glamorous pursuit flying.”17 “Our first sight of the elementary D.H. 6 prompted a look to see who was holding the string, for they looked like box kites in a strong wind. However, they were very rugged and did their job well. I was quite pleased with my instructor, Lt. [Gerald Frankcombe] Court.”17a

After seven hours of dual instruction, Heater “soloed with no difficulties on 15 February, 1918.”18 By March 20, 1918, Heater had advanced sufficiently to be recommended for his commission and was sworn in as a first lieutenant in April.19

In late May Heater arrived at Turnberry in Scotland for advanced training at the No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting and Gunnery; “quarters were in the large resort hotel and were sumptuous!”20 Writing a letter home on June 2, 1918, George Clark Sherman, also at Turnberry, described a brief holiday he took with Heater and Kenneth MacLean Cunningham at the end of May: “The Colonel let us Americans off Thursday afternoon (Decoration Day) . . . Our weekly holiday is from Friday noon until Saturday noon so Cunningham, Heate[r] and I got permission to be absent Friday morning also and went from Ayre [sic] to Glasgow Thursday evening. Friday morning we got up early and took a train to the foot of Loch Lomond and took a steamer from there and went all the way up the Loch and back again that day.”20a

Heater remained at Turnberry through the first half of June, and thus was there when his friend Reed was killed on June 5, 1918.21 In a letter to Reed’s family Heater wrote that “Dick was my best friend, we had been together constantly for nearly a year since leaving Cornell Aviation School and his going has been a big blow to me.21a It fell to Heater to go through Reed’s personal belongings and to “act with the American Aviation Office, 35 Eaton Place, London, S.W.1, as representing the next-of-kin, in settling up the estate.”21b

At some point, probably after his time at Turnberry, Heater went through a course of wireless telephony at Chattis Hill, a few miles from Boscombe Down.22 Once his advanced training was completed, Heater served for a time as a ferry pilot. Towards the end of June 1918 he was ordered to report for assignment to a squadron in France. He later recalled that on “Joining three of my Italian detachment friends [Kenneth MacLean Cunningham, Payson, and George Clark Sherman], we chanced to meet an RAF pilot who had recently returned. On learning that we were D.H. pilots, he suggested that we request assignment to a D.H.4 squadron that was fitted with Rolls Royce engines. We did so, and were assigned to 55 squadron.”23

Flying with No. 55 Squadron R.A.F.

No. 55 had been formed as a training squadron in 1916, but in January 1917 was designated a bombing squadron and became the first squadron to be equipped with DH.4s. By early March it was stationed in France, flying bombing and reconnaissance missions.24 When Hugh Trenchard’s Independent Air Force came into being on June 6, 1918, No. 55 was assigned to it. The purpose of the I.A.F.—which initially consisted of Nos. 55, 99, and 104 Squadrons (day bombing), and Nos. 100 and 216 Squadrons (night bombing)—was to carry out long-range bombing of strategic targets within Germany and to operate, as Heater put it, “without the Army having any prior claim to their service except in serious situations.”25

At the beginning of July the four men from the second Oxford detachment destined for 55, along with Philip Dietz, Linn Daicy Merrill, and Horace Palmer Wells, who were all assigned to 104, set out for Azelot, a few miles south of Nancy, where the I.A.F. day-bombing squadrons were based. “Nine months of training in England should have given the party of American pilots who left for the Independent Air Force on the last of June an idea of the sort of thing they were running into when they got to France, but most of them were unpleasantly surprised when they were bombed the first night in Boulogne, the second in Paris, the third while on their way to their squadrons in tenders, and several succeeding nights after reaching their stations.”26

Heater, in his account of “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” probably written in 1919, noted that the “methods used by the British in training new pilots who had just come to the front were not altered for the Americans, except that instead of allowing three weeks to elapse between the day of arrival and the first trip over the lines, a two week interval was used for American personnel.”27 In his own case, this period lasted but eleven days. He reached Azelot on July 5, 1918, and took part in a raid targeting the train station at Thionville on July 16, 1918.28 From that day through August 23, 1918, Heater flew fourteen missions, all but two of the bombing missions flown by No. 55 during that period. His observer on all of these missions was Alexander Stewart Allan.29

Setting out on the July 16th raid, both Nos. 99 and 55 Squadrons flew in their standard two formations of six planes each; 99 left Azelot at 11:25, and 55 followed five minutes later. The bombs dropped by 99 did a great deal of damage; the second formation from 55 added to the destruction, but most planes from the first formation, including Heater’s, encountered dense clouds, lost their way, and returned to Azelot. The next day the two squadrons targeted Thionville again, and both formations from 55, with Heater and Allan in the second, dropped their bombs in the vicinity of Thionville.

These two forays were comparatively short in both distance and duration. The next mission flown by 55, on July 19, 1918, targeting Mauser munitions works at Oberndorf, was more typical, with a flight time of four hours and twenty-five minutes. This is beyond the endurance of the standard D.H.4, but Keith Rennles, in his book on the day bombing squadrons of the I.A.F., notes that “55 Squadron rectified this problem itself with the addition of extra fuel tanks giving an improved endurance of five hours.”30

The next day, July 20, 1918, the proposed target was the Mercedes aero engine works at Untertürkheim near Stuttgart, but, as often happened, weather conditions—in this case a strong head wind—prompted the flight leader to change plans and once again to target Oberndorf. On the return journey, for the first time in Heater’s experience, the squadron encountered significant opposition from enemy aircraft, and there were several casualties. On July 22, 1918, two formations from 55 again set out to target the Mercedes works, and high winds again prompted them to change course and this time to target a gunpowder factory at Rottweil. Enemy aircraft approached them on their return journey but did no damage; the planes of 55 also, as usual, had to contend with anti-aircraft fire but this did not reach them at their altitude of 14,500 feet.

After a period of bad weather, 99 and 55 flew their next mission on July 30, 1918; Heater did not take part in this renewed attempt to target the Mercedes aero engine works. His fellow Oxford detachment member Philip Dietz, who had been transferred from 104 to 99 Squadron did; he was killed on this, his first mission over the lines. Heater later noted of the remaining men in the group of seven who had gone to the I.A.F. with Dietz that their “enthusiasm underwent a change, when Lieutenant Dietz was killed . . . , and now our trips against the Hun had more of a personal touch than they had before.”31

Heater participated in 55’s next mission on July 31, 1918, which initially was supposed to target Cologne but was redirected to Coblenz; on their return the formations flew at the bone-chilling altitude of 17,000 feet in a successful effort to avoid enemy aircraft. Another attempt was made to reach Cologne on the first of August. The distance was long enough as the crow flies, about 155 miles, but this time, rather than flying directly north, 55 initially flew northwest, crossing the lines and turning northeast at Verdun. Cloud cover over Cologne precluded sighting targets, and Düren was hit instead. Heater’s formation had set out at 5:20 a.m.; they arrived back at Azelot over five hours later, at 10:25.

Weather conditions precluded missions until August 8, 1918, when 55 undertook a shorter bombing mission (three and a half hours) targeting factories at Rombas. On the 11th and 12th, the proposed target was factories and railways at Frankfurt am Main, 150 miles northeast of Azelot. Intercepted by German planes partway into the flight out on August 11, 1918, both of 55’s formations returned without reaching their goal or dropping their bombs.

The next day, August 12, 1918, at 5:20 a.m. twelve planes from 55, including D8396 flown by Heater with his observer Allan, set out again in their usual two formations of six planes each, to bomb Frankfurt.32 A few days later, Heater described this mission in a letter home:

Monday was the worst time we’ve had since I’ve been here and from what others say it’s the worst the squadron has ever had. We went on a very long raid, I suppose the censor wouldn’t like to have me tell where, though you can find it in the papers and Fritz was certainly in fine spirit for a scrap. For over two hours he hung around following us for some distance till some new ones came along to relieve the old ones and that kept up till it was almost a bore. Altogether we must have had forty separate ones after us at different times so you may be quite sure that they kept us well entertained while we were on their side. But Fritz, though a fair flyer, has less nerve than an old house cat and hangs away behind our formation shooting away good ammunition and hoping a stray shot may find one of us. During this raid though a few of them got desperate and came after us as though they meant it but they had better have stayed back because we got 6 of those who had nerve but didn’t know how to use it. I hoped to bring one down with my front gun, he broke up in the air while my observer brought down another and together with another observer set fire to another boche plane, so we did our share of the fighting.33

The “old house cat” behavior was likely prompted by the skilled formation flying of 55. Rennles notes that “although numerically superior . . . [the enemy planes] were not aggressive, preferring to keep their distance due to the tight formations being flown by 55 Squadron and the concentrated fire they gave out.”34 Indeed, tight formation flying was emphasized and consistently practiced by 55 and would prove to have been valuable training later when Heater came to lead the U.S. 11th Aero. When the planes of No. 55 Squadron reached the vicinity of Frankfurt this day, the enemy aircraft broke off their attack, and 55 dropped their bombs and took photos. In the course of the raid, according to one account, “One enemy machine was shot down in flames and seen to break up, another seen to crash into a wood, two others were driven down out of control, and one was driven down.”35 The planes of No. 55 Squadron touched down again at Azelot at about 10:50 a.m., making this probably the longest duration raid Heater participated in.

Apropos enemy planes downed, Heater later remarked, “In this bombing work the combats with Enemy Airmen were of such a nature that individual victories were very difficult to credit.”36 Nonetheless several pilots and observers from 55 and 104 were credited with victories on August 12, 1918, including, by his own and other accounts, Heater.37 Among the German casualties for which 55 and 104 were apparently responsible that day was Karl Kallmünzer, who died of injuries sustained when he crash landed after aerial combat over Wasselonne.38 Had the Americans of the I.A.F. realized this, they would doubtless have felt some satisfaction at having avenged the death of Philip Dietz, who is believed to have been brought down by Kallmünzer.

The next day (August 13, 1918) 55 set out again with Frankfurt as a goal, but bombed Buhl instead. Heater did not fly with them that day, but was in the second formation from 55 on August 14, 1918, when they set out initially for Cologne, but were diverted by cloud cover and a large number of enemy planes to Offenburg.39 The next day 99 and 104 flew missions, but 55 did not. On August 16, 1918, the target was once again Cologne, and once again a decision was made not to try to make the whole distance, but instead to aim for the railway junction at Darmstadt, the only time this city was targeted by the I.A.F. Comparatively little damage was done, and 55 suffered significant losses during the return flight. Heater and Allan are for the second time recorded as flying D.H.4 D8396, which on this mission served as the “photo machine”; Allan brought back eighteen photos.

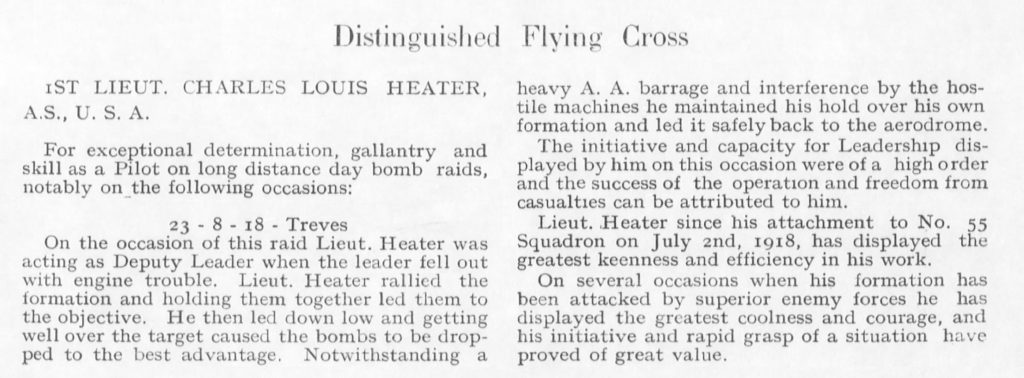

Except for one-man reconnaissance flights, 55 did not cross the lines again until August 22, 1918. As so often, the hoped-for target that day was Cologne, but once planes were in the air and encountering strong wind, the decision was made to head for the secondary target, in this case Coblenz. This, however, became irrelevant for Heater, because his engine was not functioning properly, forcing him to return early in this, his penultimate mission with 55. On his last mission with 55 the next day, it was the leader of his formation, John Ross Bell who had to drop out with engine trouble, and Heater for the first time took the lead position in his formation. Duncan Ronald Gordon Mackay, leading the other formation, realized that huge cloud banks meant Cologne was once again out of the question. He initially tried to lead the two formations to Coblenz, but was foiled by clouds in this effort as well. A railway station east of Treves (Trier) was bombed before the squadron turned home. In connection with his leadership on this flight, Heater later remarked that “It was fortunately an easy raid, so my good fortune prevailed.”40 Like so many of his fellow pilots, Heater was modest. His leadership on this raid in fact earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross, as he learned a short time later.41

On August 24, 1918, Frank Purdy Lahm, who was with the Air Service of the American First Army, noted in his diary: “Ran over to Azelot. . . . Brought Lt. Heater, who has been in one of the British squadrons, to Colombey where he reports to take command of one of our new bombing squadrons.”42 Heater recalls that “Around the end of August . . . I was told to report to U.S. at Colombey-Les-Belle [sic] and take command of a new U.S. squadron. I found it was an artillery observation squadron, so I was told to await a day bombing appointment.”43 He had some leave coming; it wasn’t until September 21, 1918, that he arrived at Amanty to take over as commanding officer of the U.S. 11th Aero Squadron.

The 11th Aero had been assigned to the First Day Bombardment Group of the American First Army on September 10, 1918; the Group was created that day to support the St. Mihiel Offensive—which began on September 12, 1918. After two days (September 12 and 13, 1918) of flying protection patrols, the 11th flew their first bombing mission and experienced their first losses on September 14, 1918—two planes and four men did not return.44 They flew mainly bombing missions for the next three days without losses, by which time the St. Mihiel Offensive had largely succeeded. On the 18th, however, despite inclement weather, they were ordered to bomb Lachaussée.45 Their squadron C.O., Thornton Dayton Hooper, is reported to have had serious misgivings and, though not required to participate, would not send his men out without going himself.46 The report at the end of the day reads “One team returned to field at 18:30 o’clock. Five teams missing.”47

In five days the 11th had lost fourteen men, including their C.O. Under different circumstances, a squadron might conceivably have taken this in stride, but the 11th felt it had been ill-used by the “swivel chair commanders.”48 “No squadron could have been more completely broken than we were that night. . . . Confidence in the higher officers of the service, who were supposed to be guiding operations, was gone, and with that confidence had gone respect.”49 This was the devastated and demoralized squadron that Heater was asked to take charge of.

The St. Mihiel Offensive was now over; plans were already well underway for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The First Day Bombardment Group remained for a time at Amanty; Pershing wished to continue to focus German attention on the St. Mihiel region, away from the secret buildup for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. There are conflicting accounts of expectations for the First Day Bombardment Group during the period between the two offensives. By one account, they were “to carry out bombing expeditions to objectives east of the Moselle river. The object was to convey the impression of an impending attack on Metz, and thus avert the enemy’s attention from the real point of attack.”49a Another states that their targets were along the Meuse, west of the Moselle. 49b Operations reports indicate, however that no missions were undertaken from September 19 through September 25, 1918. 49c According to the History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., “Major Dunsworth . . . tried to send us over on a raid almost as soon as Heater arrived. When Charlie refused and told Dunsworth that he would not send the 11th across until they were in better shape, he saved us but did not add to his own popularity with the incompetent commander.”49d

During this period before the start of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive on September 26, 1918, Heater lectured his pilots “on the primary importance of close, tight formations and also my confidence in the D.H.4, although I had not flown one with a Liberty motor.”50 He had them watch as he put a D.H.-4 through its paces, and whenever weather permitted he had them practice formation flying.51 Meanwhile, there was consultation among squadron leaders and higher-ups that led to the decision to fly larger formations over the lines—twelve to eighteen planes, combining planes from more than one squadron as needed to make up a flight.52 The 11th’s diminished roster was restored to full strength by the arrival of new pilots, including Dana Edmund Coates, Ralf Crookston, Uel Thomas McCurry, and George Dana Spear from the second Oxford detachment. The squadron history describes the result of these various changes as “the reconstruction of a broken outfit and its complete transformation into a high grade, competent unit, confident of its ability and proud of its record.”53 Heater’s leadership contributed significantly to this transformation.

On about September 24, 1918, the three squadrons (96, 20, and 11) moved about twenty miles northwest from Amanty to Maulan as part of the extension of the American First Army’s front from the St. Mihiel sector to the Argonne Forest.

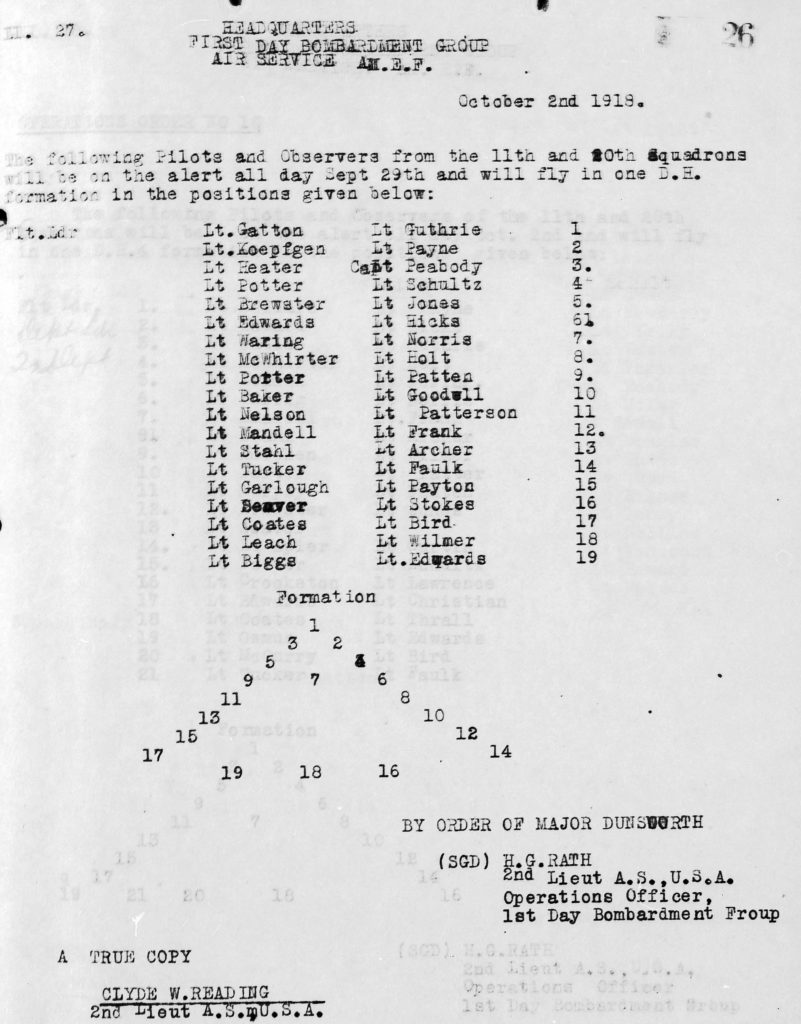

The administrative duties of a C.O. prevented Heater from flying regularly on missions, but he did take part in four raids. On September 29, 1918, twenty D.H.-4s from the 11th and 20th Aero Squadrons took off from Maulan at 4:30 p.m., with Grandpré, about fifty miles to the north, as the objective. Of these, six planes, including Heater’s, reached nearby Marcq and dropped their bombs, returning to Maulan at 6:40 p.m.; this mission was typical in being much shorter than those flown by No. 55 Squadron.54 Heater’s observer was George Peabody, making his first trip over the lines and, according to a squadron history, not yet entirely clear on his duties.55

Heater (recently promoted to captain) flew his third mission with the 11th Aero on October 18, 1918, this time with Sigbert Albert George Norris as his observer.57a The single mission that day consisted of four flights, one each from the 96th, the 20th, the 11th, and—its first raid—the 166th, for a total of perhaps as many as fifty-two planes setting out, not counting the Spads that accompanied them on this, as on many of their missions, for protection.58 The target was Bayonville, a short distance north of Grandpré. Heater recalls this as a raid during which propaganda leaflets were dropped, and this may have been the case, but it certainly was also a bombing mission.59 Norris recorded that Bayonville was bombed from a height of 14,500 feet. Enemy aircraft were encountered but were unable to do any damage. “A Fokker patrol of five machines nosed inquiringly around the formation but were quickly driven off by Spads. Two Huns went down in flames, while all of our machines returned safely.”60

On November 3, 1918, the 11th participated in a morning and an afternoon mission; Heater, again with Norris as his observer, took part in the afternoon raid.61

On this raid one of our machines was fitted with a camera for photographing the objective as the bombs burst, in order to confirm our observers’ stories of direct hits. This machine was piloted by Captain Heater with Lieutenant Norris as observer, flying a rear position. In order secure plenty of pictures Heater dropped back after the bombing and remained over the town, while Norris struggled with the camera. The cold at that altitude, about 15,000 feet, was so intense that the oil or moisture on some part of the camera mechanism had frozen, and they were forced to give it up finally without exposing any of the plates.62

Worse yet, frost blurred Norris’s goggles; when he removed them, the cold air nearly blinded him. His defensive firing at two enemy planes was thus ineffective. “Things began to look bad so Heater took a chance on scaring Fritz by pulling into a steep turn and heading straight for the two Huns, his front guns wide open. The trick worked, for the two Huns pulled away.”63 Two enemy aircraft were either destroyed or driven down out of control during this raid, and fourteen of the men (seven teams of pilot and observer) were credited.64

The First Day Bombardment Group flew its last missions on November 4 and 5, 1918; Heater did not participate in either of them (and the 11th did not actually cross the lines on the 5th).

After the armistice Heater remained with the squadron into the new year, overseeing the dispersal of equipment and men. He noted that “My last flight was returning the last of 11 Squadron’s D.H. 4 planes to the Colombey depot.”65 He sailed to the U.S. on the S.S. Northland, arriving in Philadelphia February 21, 1919.66

His work after the war, like his father’s was connected to railroads; he worked for American Steel Foundries, a maker of railway equipment, eventually becoming a company vice president.67

mrsmcq February 9, 2018; misc. revisions & additions June 13, 2023

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

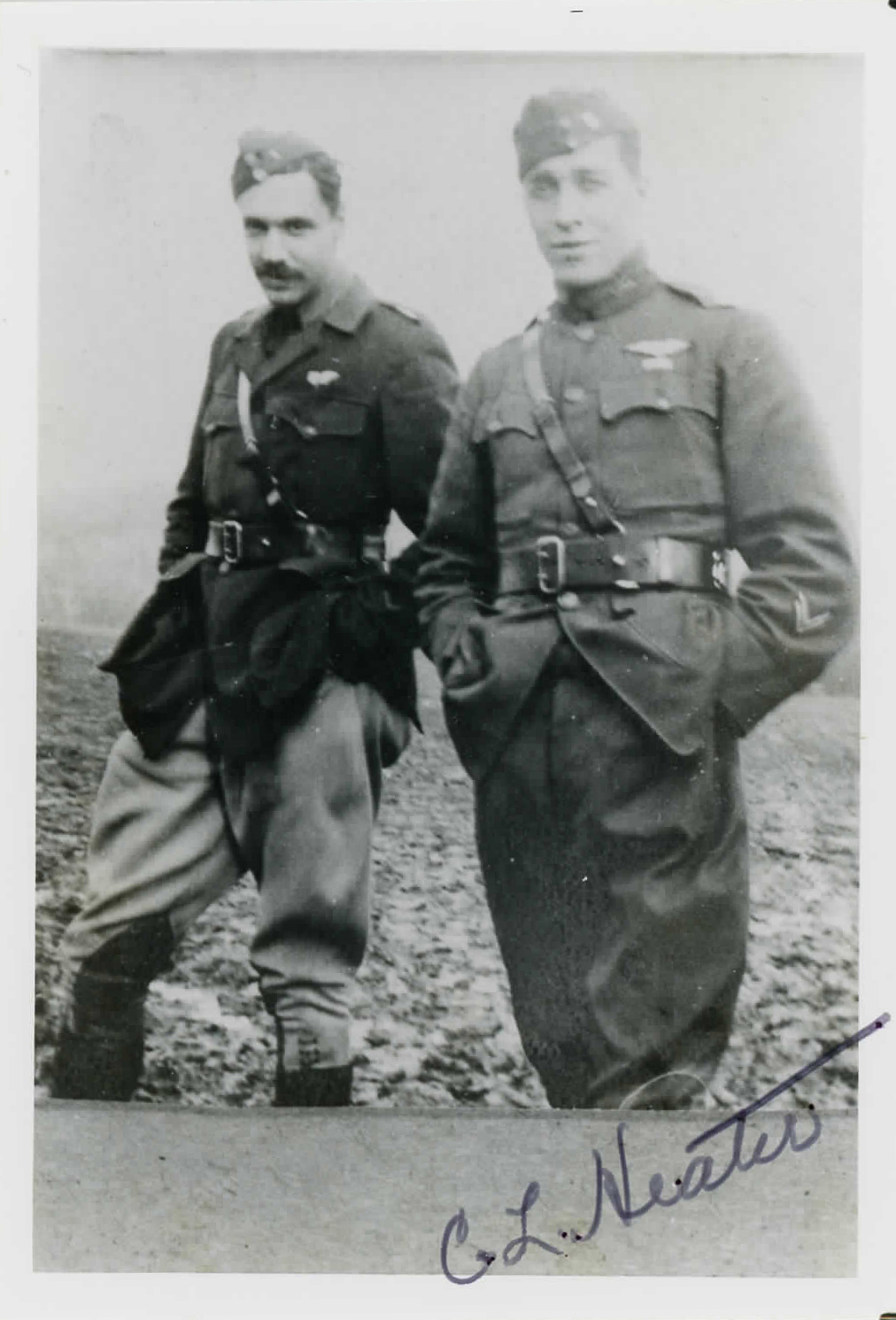

1 Heater’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Charles Lewis [sic] Heater. His middle name is sometimes spelled “Lewis,” but the signature on his World War I draft card, as well as his World War II draft card (apparently filled out by himself), indicates that he spelled it “Louis” (Ancestry.com, U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942, record for Charles Louis Heater). His place (“last residence”) and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935–Current, record for Charles L. Heater. The photo is cropped from a larger photo (see here), courtesy of Stephen Skinner WWI Archives, https://thestandfrankluke.weebly.com.

2 Information on Heater’s family is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 “Mandan Boy Appointed.”

4 “Terminated a Military Career.”

5 Purdue University, The Debris for 1917, p. 115.

6 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

7 On La Guardia, Hooper, Somewhere in France, September 24, 1917; Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 259. For Hooper on Heater, see Hooper, Somewhere in France, September 30, 1917 (continuation of letter of September 21, 1917).

8 Hooper, Somewhere in France, September 30, 1917 (continuation of letter of September 21, 1917).

9 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 259. Most of the training was actually with the Royal Flying Corps, which did not become the Royal Air Force until April 1, 1918. Heater may be referring to John Biddle (1859-1936), who passed through England on his way from France to the U.S. in October 1917, and who was on the A.E.F. staff in London in 1918. But it seems more likely that Heater has misremembered the name of Gordon Robinson; see the reference to the latter in the page for Leo McCarthy. For an account of training in Italy—not obviously more fraught with challenges than in England—see George M. D. Lewis’s account in Chapter 3 of Lewis, ed., Dear Bert.

9a “Thinks Often of Home State.”

10 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 259.

11 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 259.

12 “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers. On 36, see See Philpott, Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 402, and Wikipedia, “RAF Usworth.”

13 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 259. The other men assigned to No. 36 had been at ground school at either M.I.T. or Princeton.

14 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 259.

15 Castle’s remark is reported by Foss, in a diary entry for January 12, 1918.

15a The men were probably guests of the widowed Candida Louise, Marchioness of Tweeddale.

16 On 6 T.D.S. and the planes used, see the November 25, 2006, contribution by mickdavis at “Introduction and new Question TDStations.” See also Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 294.

17 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 260.

17a Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 260.

18 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 260.

19 See cablegrams 756-S (March 20, 1918) and 1028-R (April 2, 1918).

20 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 260.

20a “Lieutenant Sherman is Anxious to Sail.”

21 Heater, in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 260.

21a “Official Report.”

21b Ibid.

22 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Charles Louis Heater.

23 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 261.

24 On 55, see Barrass, “No 51 – 55 Squadron Histories.”

25 On the composition of the I.A.F., see Rennles, Independent Force, pp. 6-7; Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 261. There is considerable controversy surrounding the I.A.F. Chapter 11 of Wise’s Canadian Airmen and the First World War provides an account and an assessment based on original documents that is worth reading.

26 Heater, [Informal account], p. 124.

27 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing,” p. 117.

28 For his date of arrival, see Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 262. Although Heater wrote the account presented by Skinner many years after the fact, he apparently had his log book to hand; his arrival date was memorable, being a year after his “enlistment date at Cornell.”

29 Unless otherwise noted, information on Heater’s work with 55 is taken from Rennles, Independent Force. While Rennles provides a “select bibliography” (p. 211) and some account of the difficulties of researching I.A.F. squadrons (pp. 10–11), he does not document sources in his main text. While I have found no reason to doubt his accuracy, the lack of documentation makes it difficult to verify information or to check whether a particular source might provide further information.

30 Rennles, Independent Force, p. 7. Heater notes ([Informal account,] p. 125), that D.H.4s would “get a higher altitude and more speed [than the D.H.9s of 99 and 104], due to the more refined and higher powered motor, so it was natural that the longer work should fall on them.” Descriptions of the D.H.4 and D.H.9 don’t attribute an advantage in speed to the D.H.4, but with a service ceiling of 18,000 feet, it could fly about 1,250 feet higher than the D.H.9 used by the I.A.F. See Harris and Pearson, Aircraft of World War I, passim.

31 Heater, [Informal account], p. 126.

32 The records available to Rennles for his Independent Force generally fail to list plane numbers. Only for two flights, those of August 12 and 16, 1918, does Rennles have the number of the plane assigned to Heater and Allen. In both cases it was D8396, suggesting that this may have been his regular plane. On August 30, 1918, after Heater had left the squadron, D8396 was shot down, and both the pilot and the observer were killed; see “RAF 55th Sqdn., Airmen story” (where there are photos of the crashed plane).

33 Heater, letter of August 15, 1918, to Mr. and Mrs. J. R. Heater.

34 Rennles, Independent Force, p. 82; see also Miller, The Chronicles of 55 Squadron, R.F.C. and R.A.F., p. 104: “enemy aircraft . . . did not press the attack with much vigour, owing to our excellent formation.”

35 Miller, The Chronicles of 55 Squadron, R.F.C. and R.A.F., p. 103.

36 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 122.

37 What I take to be the official I.A.F. communiqué for August 12, 1918, (of which I have a scan courtesy of Mike O’Neal) credits Heater’s observer, Allan, with a plane driven down out of control. Heater’s own version of the communiqué, however, on p. 122 of his “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” lists himself, as does “Confirmed Victories U.S. Air Service Officers with Independent Air Force.”

38 See Rennles, Independent Force, p. 82, where he credits the downing of Kallmünzer to 55. However, given that he was apparently shot down over Wasselnheim (Wasselonne) not far from Hagenau, 104’s target, it seems to me more likely that 104 was responsible. Rennles notes Kallmünzer had been in “combat with DH4s,” but it would have been understandable if 104’s D.H.9s had been mistaken for D.H.4s in German reports.

39 “Confirmed Victories U.S. Air Service Officers with Independent Air Force,” credits Heater with a victory on this raid; Rennles’s account on pp. 87–88 of Independent Force, makes no mention of this, nor does the I.A.F. communiqué for that day.

40 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 263.

41 Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 263. The citation can be found on p. 13 of “List of Honors and Awards, No. 2, Air Service Am. E.F.” Rennles, Independent Force, p. 100, is mistaken when he states that the DFC “was not granted”; Rennles’s brief biography of Heater on p. 100 is in general not reliable.

42 Lahm, The World War I Diary of Col. Frank P. Lahm, Air Service, A.E.F., p. 121.

43 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 263.

44 The “Summary of Operations of First Day Bombardment Group” states, p. 2, “The 11th lost a plane near Chambley,” but other sources, including Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, make clear that two planes were lost.

45 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 153: “La Chaussee”; cf. Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II. “Summary of Operations of First Day Bombardment Group,” p.3, specifies nearby Mars-la-Tour as the target; cf. Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 103–04.

46 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 153.

47 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 54.

48 Hooper, quoted in History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 153.

49 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 157.

49a Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p 371.

49b Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I , vol. 2, pp. 234 and 239.

49c Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 105–06.

49d History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 157. The negative assessment of Dunsworth, which appears again later in Sloan’s Wings of Honor, may be unfair. A few years after the war Howard Grant Rath, a pilot with the 96th Aero, testified at hearings before the President’s Aircraft Board that “Dunsmore” [sc. Dunsworth] protested, to no avail, against Mitchell’s insistence that planes of the 1st Day Bombardment Group fly under extremely adverse conditions. See United States, President’s Aircraft Board, Aircraft: Hearings before the President’s Aircraft Board, p. 1110. I am grateful to Hugh T. Harrington for bringing Rath’s testimony to my attention.

50 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 264.

51 Conventionally “DH.4″ refers to the British built, original version of the plane; “DH-4″ to the American built plane with the “Liberty” engine.

52 Maurer, ed. The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p. 372.

53 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 159.

54 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 111-12. The brief account of this raid on p. 55 of Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], differs in some details.

55 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 161.

56 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 55.

57 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 165.

57a Norris, who had been assigned to the 11th on September 12, 1918, also served as squadron operations officer. In 1919 he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions while flying with pilot William Wallace Waring on September 26, 1918 (see “Pershing Honors New York Aviators”).

58 I take the number “fifty-two” from the list of planes provided on pp. 129-30 of Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations.” Hudson, Hostile Skies, refers to a “forty-two-plane formation,” and mentions seven planes from 166; while Rath lists ten planes from the 166th setting out, although three teams “did not reach the objective.” Similarly, Rath lists sixteen planes from the 11th setting out; Norris notes that sixteen set out, with eleven reaching the objective.

59 Heater in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 264. The leaflet reproduced on p. 266 of this article cannot have been one dropped on the 18th, quoting as it does an article printed in a German newspaper on October 28, 1918, and referring to the Armistice of Villa Giusti (signed November 3, 1918).

60 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 167.

61 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 146, lists “Capt. Sellers” flying with Norris, but this is probably an error.

62 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 173.

63 Ibid.

64 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 57, states that the planes “were driven down out of control.” Sherman, General Orders Number 27, paragraph 20, refers to “the destruction, in combat, of two enemy Fokkers.” Lists of victories in Gorrell M.38 indicate that each man was credited with one victory, rather than two, for this day. But see also Thayer, America’s First Eagles, p. 320; and U. S. Air Service Victory Credits World War I, p. 27.

65 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 268.

66 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list, Officers, S. S. Northland, departing Brest February 8, 1919, arriving Philadelphia February 21, 1919.

67 See “Supply Trade.”