(Madrid, New York, April 1, 1894 – near Cuvilly, France, June 11, 1918).1

Oxford, Grantham, Doncaster, Ayr ✯ London, France, 73 Squadron at Beauvois ✯ 73 Squadron at Fouquerolles ✯ June 11, 1918, and after

Douglass was born into a family of farmers in upstate New York not far from the Canadian border; both of his grandmothers were born in Canada.2 Although not apparently a blood relation of his father, his mother was also a Douglass.3 After graduating in 1912 from high school in the town of Norwood, a few miles east of his birthplace, Douglass entered Syracuse University.

There he was active on school newspapers, becoming an editor of both The Daily Orange (the Syracuse University student newspaper) and The Empire Forester (newspaper of the School of Forestry). In 1916 he graduated from the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse University. After a brief stint as assistant advertising manager for a Syracuse manufacturing company, he moved to Washington, D.C., to join the staff of the journal American Forestry.4 Articles by him appear in the June and July 1917 numbers of that publication.

Douglass enlisted on June 20, 1917, and was sent to the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University.5 When he graduated from ground school on August 25, 1917, he was one of the eighteen men from this class selected for training in Italy and thus one of the 150 men of the “Italian” or “Second Oxford Detachment.” On September 18, 1917, the detachment boarded the Carmania at New York and sailed initially to Halifax. There the Carmania joined a convoy for the Atlantic crossing.

Oxford, Grantham, Doncaster, Ayr

Shortly after they arrived at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men learned that they were going not to Italy, but to Oxford, where they would repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics. Douglass’s fellow detachment member Murton Llewellyn Campbell wrote in his diary on October 5, 1917, that “[Allison Henderson] Chapin, Douglass, [Roland Hammond] Ritter, and I are rooming together and enjoying a very comfortable place”; they were among the approximately ninety men from the detachment who were housed at Christ Church College. Like many of the cadets (as they were now called) and Oxford students generally, Douglass had his turn flouting curfew rules. Campbell writes of a late night return for which he (Campbell) “got confinement.” “About 1 min. after I got in Dug [sic] appeared with dirty hands and a long story of how many walls he had crawled.” The next night, Chapin was the one late in, and “Dug and I put out a ladder over the wall for his benefit.”6

On November 3, 1917, approximately 130 of the men, including Douglass, left Oxford to go to Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire, to machine gun school. Two weeks later, fifty of the men from Grantham, including Douglass, were assigned to flying schools.7 On November 19, 1917, Murton Campbell wrote in his diary that “Doug and I are posted at Doncaster, together with 8 others.” Douglass was at No. 41 Training Squadron, Campbell at No. 49 (both at Doncaster in south Yorkshire).8 Joseph Kirkbride Milnor noted Douglass’s arrival at South Carlton, along with Weston Whitney Goodnow, on December 23, 1917, and Murton Campbell reported seeing Douglass at South Carlton on December 28, 1917, among a group “posted to the 45 Pool Squadron.”9 Milnor, who remained at South Carlton for a time, does not mention Douglass again, which suggests that Douglass was posted away from South Carlton around the turn of the year.

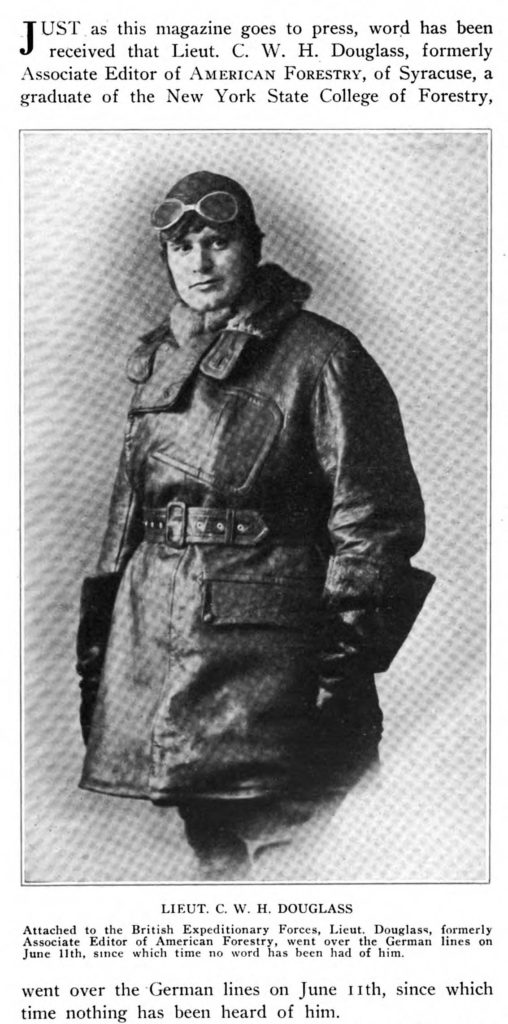

An excerpt from a letter written by Douglass and printed in American Forestry in February 1918 summarizes his training through the early part of 1918: “We spent six weeks (about) in an English ground school, repeating the work we had done at home, and then after a fortnight in machine gunnery schools we were scattered in small groups among the flying schools all over England. I’ve completed my preliminary training on a staid and dignified old buss that we used to call an ‘animated lawn mower’ and am now at an advanced school for work in the faster machines. Expect to fly scouts, the wasplike machines that run around at about 130 miles per hour. Great sport we all agree.”10 Douglass’s R.A.F. service record gives no details of his training, but he evidently learned to fly Sopwith Camels. By early March 1918 he had completed enough training to be recommended for his commission, and Pershing forwarded the recommendation to Washington on March 13, 1918. The cable confirming the appointment is dated March 29, 1918.11 Douglass was called to active service on April 9, 1918, while stationed at Ayr.11a

London, France, 73 Squadron at Beauvois

In the first part of May Douglass was in London. The evening of May 8, 1918, he went to the theater there to see “Maid of the Mountains” with fellow second Oxford detachment member Parr Hooper (whom he had known since their time together at O.S.U. ground school) and Hooper’s Baltimore friend Paul Verdier Burwell.12 A few days later, he and Hooper were posted to No. 2 A.S.D., i.e., sent to France, probably to a pilots pool near Berck-sur-Mer south of Boulogne, to await orders to join a squadron. Hooper was soon assigned to No. 32 Squadron R.A.F. to fly S.E.5a’s. On May 17, 1918, Douglass was assigned to No. 73 Squadron R.A.F., along with Burr Watkins Leyson, also of the second Oxford detachment, as well as Richard Mortimer of the first Oxford detachment.13 Another American, Harold Clement Hayes, was assigned to 73 the same day, as was the Yorkshire-born Canadian Thomas Geoffrey Drew-Brook; another American, Roland Dudley Doane was assigned the next day.14 Don Minterne, in his history of the squadron, writes that around this time an “order had been promulgated that all Camel squadrons would have an increase in establishment to 27 pilots and 25 aircraft,” (up apparently from twenty-one and eighteen), and the result was this influx of pilots from across the pond.15

No. 73 was a Camel squadron stationed at Beauvois, about thirty miles inland from the coast, due east of Berck. It had moved to this location, with brief intermediate stops, after being driven from Champien during the initial phase of the German Spring Offensive in the latter part of March 1918.16 Rather than being part of a brigade attached to a particular British army, No. 73 Squadron was among those (including also No. 32 Squadron) in the 9th (Day) Wing of IX Brigade, which served directly under R.A.F. headquarters in France. R.A.F. HQ could send the IX Brigade squadrons wherever they were most needed.17

According to the No. 73 Squadron record book, Douglass made his first flight with the squadron on May 19, 1918.18 Flying Camel D1812, he and three others—William Samuel Stephenson, Emile John Lussier, and Doane—set out at 6:30 p.m. “cross country.” Stephenson and Lussier, the two experienced pilots, returned at 7:10, while the new men, Douglass and Doane, arrived back at the aerodrome fifteen minutes later.

In their book about the U.S. 17th Aero Squadron, Otis Lowell Reed and George Roland state that “standing field orders forbade a pilot to cross the line of battle before he had been in France three weeks and at the front two.” 19 Similarly, Charles Louis Heater, pilot of No. 55 Squadron R.A.F. and the U.S. 11th Aero, recalled that the “British have a rule that no pilot goes over the lines until three weeks after they have joined the squadron. . . .”20 73 seems not to have gotten the memo—and the more I look at individual pilots’ experiences as reflected in squadron record books, the less I am convinced that such field orders were uniformly enforced. Douglass’s experience is a case in point. On May 20, 1918, three days after his arrival at Beauvois, on his second flight with No. 73 Squadron, Douglass, flying Camel D6456, took part in an eighteen plane offensive patrol that flew well into enemy territory. Maurice Le Blanc-Smith, commander of B flight, reported sighting a formation of six Albatros scouts between Douai and Marquion; Geoffrey Arthur Henzell Pidcock, commander of A flight, to which Douglass was apparently assigned, reported a formation of five enemy scout planes near Cambrai and also noted an explosion at Seclin. These sightings suggest that the formation flew about forty-five miles east southeast towards Cambrai, and then via Marquion and Douai towards Seclin, about twenty-five miles north of Cambrai, and then back to the aerodrome (or perhaps first towards Seclin and then south)—all within German-held territory. Douglass landed back at Beauvois fifteen minutes behind the other members of his flight, having been in the air two hours and ten minutes. Not until after this mission did he take part in an introductory line patrol. Le Blanc-Smith led the six men new to 73 (Leyson, Douglass, Mortimer, Hayes, Drew-Brook, and Doane) as well as Bengal, India-born Keith William Allardyce Symons (who had been posted to 73 on May 8, 1918), on a flight of a little over an hour the evening of May 20, 1918.21

Douglass apparently did not fly on May 21, 1918, but did get in some firing practice the next day. The morning of May 23, 1918, he flew another offensive patrol; his was one of sixteen planes in three flights (six, six, and four). The record book does not indicate what the objective was, but C flight, led by Hubbard, reported firing at troops in Ichtegem northeast of Diksmuide, thus about sixty miles northeast of Beauvois and about thirty-five miles north of Seclin, where Pidcock had seen an explosion during the patrol of May 20, 1918—73 was covering a large portion of the British front. Both of the second Oxford detachment pilots on this mission, Douglass and Leyson, encountered difficulties on their return. Leyson landed at Maisoncelle, not far from Beauvois, while Douglass, in Pidcock’s A flight, got lost and landed at “Clairmaris,” presumably Clairmarais, about thirty miles north of Beauvois.

Weather apparently precluded flying the next day. Although Leyson did some practice and “general flying” on May 25 and 26, 1918, the record book does not indicate any flying for Douglass, and, in general, for whatever reason, he did significantly less non-operational flying than Leyson. Around mid-day on May 27, 1918, the planes of No. 73 Squadron set out on an offensive patrol, now at full strength in three flights of six planes each. Douglass flew Camel D6476 with Pidcock’s A flight. Their mission this time apparently took them due east; on this otherwise uneventful patrol they reported seeing three Albatros aircraft leaving an aerodrome at Douai.

After two days of no flying, Douglass took part in his fourth offensive patrol on May 30, 1918. Once again there were three complete flights of six planes each, all recorded as setting off at 5:30 p.m. An hour later B flight leader Le Blanc-Smith noted a formation of five enemy aircraft east of Bapaume, about thirty miles southeast of Beauvois. With the exception of this sighting and some rounds fired by C flight leader William Henry Hubbard at Eterpigny, the mission was uneventful, and all the planes returned safely after two hours and twenty-five minutes in the air. Douglass took part in two similar offensive patrols the next day, as well as one the morning of June 1, 1918. Almost immediately upon his return from this seventh offensive patrol, Douglass took off in Camel D1890 (previously flown by Pidcock), “test flying.” Late the next afternoon (June 2, 1918), he flew this same machine “cross country.” Returning to the aerodrome he, according to the record book, “crashed on landing”; according to Sturtivant and Page’s Camel File he “Flew into hangar landing downwind.” Douglass was not hurt, but the plane was sent to a repair park.

73 Squadron at Fouquerolles

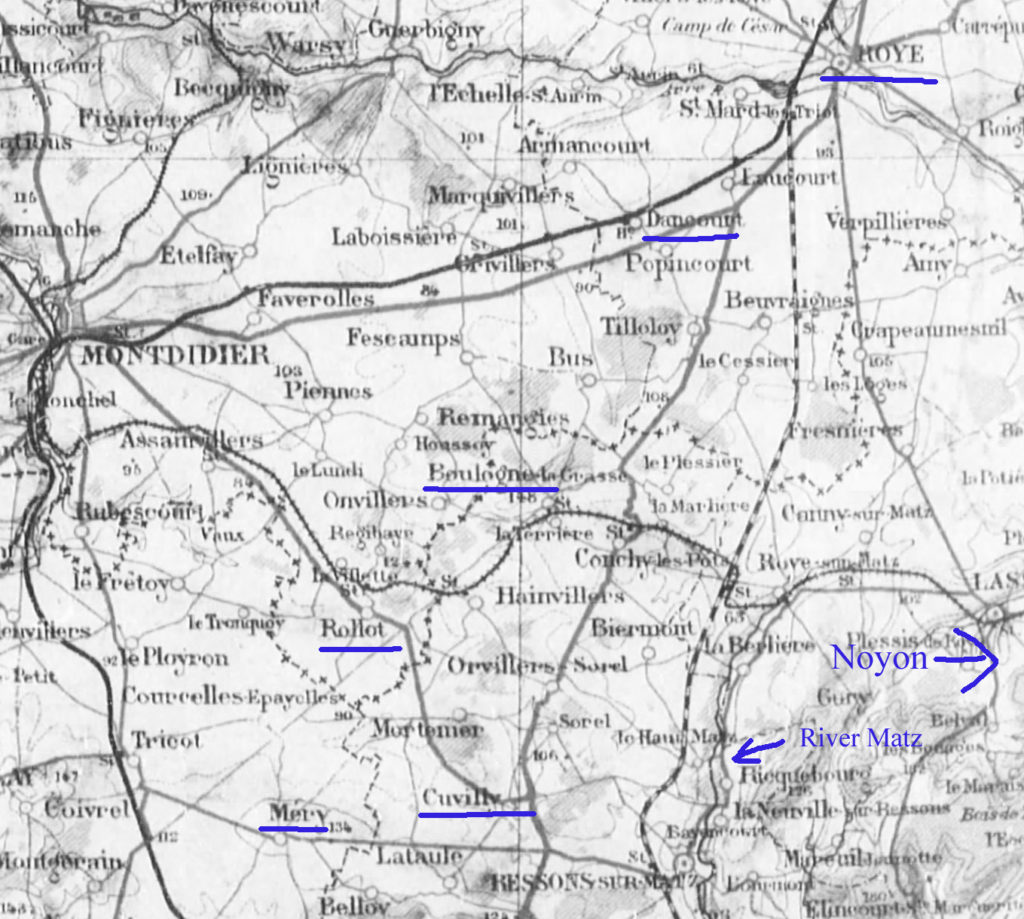

On June 3, 1918, the squadron relocated from Beauvois to Fouquerolles near Beauvais, seventy miles to the south. The French and British were aware that the next phase of the German Spring Offensive would take place in early June between Montdidier and Noyon, and IX Brigade R.A.F. sent most of its squadrons, including 73, to this front in anticipation of the German attack. Twenty-three pilots and planes from No. 73 Squadron took off from Beauvois shortly after 8:00 a.m. to make the hour-long flight; ten of them broke their tail skids on landing at the poorly prepared new field. Douglass, flying Camel D6476, had the misfortune to crash on landing again—Sturtivant and Page again describe him as having “Landed downwind” and overturning. Douglass was not hurt, but the plane was no longer usable.

Eighteen of 73’s twenty-nine pilots, including Douglass, flew a line patrol late the afternoon of June 4, 1918, to familiarize themselves with the new area. Offensive patrols began the next day. Douglass flew D1814 as part of a two-flight offensive patrol the next afternoon. The record book states without remark that he arrived back at the aerodrome at 5:40 with the rest of the patrol. Sturtivant and Page, however, in their notes on D1814, indicate that Douglass made a bad landing and overturned and that the machine was sent to a repair park. If this was, indeed, his third crash, it must have been pretty unnerving. Nevertheless, the next day he ferried in a new Camel, D1962, and flew it in an uneventful offensive patrol the evening of June 7, 1918.

There was more to report the evening of June 8, 1918, when Pidcock led his six-man flight, including Douglass, well across the lines to Roye, where “Two formations of 3 Fokker Bi-planes [were] seen and engaged” at 10,000 feet. William a’Becket Probart received credit for bringing down one of the Fokkers near Andechy, northwest of Roye.22 Two further Fokker formations were sighted, but not engaged. All pilots returned safely, although Probart had to make a forced landing at Crèvecœur-le-Grand twelve miles north of Fouquerolles.

Douglass was one of seventeen pilots who set off on an offensive patrol at 5:15 a.m. on June 9, 1918, the opening day of the Montdidier-Noyon Offensive; all planes returned an hour and fifty-five minutes later with, rather surprisingly, “nothing to report.” That afternoon, however, the pilots of No. 73 Squadron began very dangerous work. H. A. Jones, in an account the R.A.F. during this period, describes their activity: “The IX Brigade was employed during the three days of the main battle on low-flying attacks, during which a total of sixteen tons of bombs were dropped and 120,000 rounds of machine-gun ammunition were fired. The reports of the pilots reveal that targets of troops and transport were plentiful, and it would appear certain that heavy toll was taken.”23 Thus the Camels of No. 73 Squadron, designed for high, agile, fast flying, were repurposed as bombers and low-flying machine-gunners.

Shortly after noon on June 9, 1918, No. 73 Squadron began sending out ground strafing formations made up of three planes each every half hour, flying towards the Matz River, west of Noyon, where German troops were pushing forward. Douglass was in the eighth and last flight of the day; he, Lussier, and Alexander McConnell-Wood took off at 8:00 p.m. Lussier and Douglass each fired 700 rounds on transport billets, probably in the vicinity of Boulogne-la-Grasse, about seven miles east southeast of Montdidier. They arrived back at Fouquerolles at 9:00 p.m. (McConnell-Wood made a forced landing at nearby Breteuil).

Ground strafing recommenced the next morning, with the first pilots taking off at 4:05 a.m. Douglass and Lussier were the fourth team, setting off at 5:30 a.m. The record book remarks column for Douglass reads “500 r[oun]ds fired at Railroad siding, transport in various villages. 2 bombs Dancourt [?] on a chateau.” He arrived back at 6:50 a.m., twenty minutes after Lussier. Leyson, who had set off not long after Douglass, did not return, and it was eventually learned that he was a prisoner of war.

June 11, 1918, and after

The first mission undertaken by No. 73 Squadron on June 11, 1918, is labeled in the record book an offensive patrol, but it might as well have been labelled “large group ground strafing.” Seventeen planes, including Douglass’s D1962, took off at 9:40 a.m.; they fired rounds at troops and transport in the vicinity of Courcelles and Rollot. All returned safely, although Harry Jenkinson and Symons considerably after the others.

Beginning at one o’clock that afternoon, pilots took off in successive pairs on ground strafing missions. Douglass, flying D1962 and paired with Owen Morgan Baldwin, set off at 1:45 p.m. The record of Baldwin’s activity in the record book and his combat report places them in the vicinity Méry-la-Bataille and nearby Rollot, flying at about 1600 feet. In his combat report Baldwin writes that “Whilst on Ground Strafe with Lieut. Douglass this afternoon we dived on two two-seater E.A. 200 feet below, I singled out one, and fired a burst of about 200 rounds into it. . . . [It] was seen to crash E. of Mery. Almost immediately, I was dived on by a formation of Fokker Biplanes (seven or eight), one of which I saw on the tail of a Camel. . . .”24 This occurred about 2:15; the Camel was probably that of Douglass, and the Fokker on his tail may have been that of Olivier von Beaulieu-Marconnay of Jagdstaffel 15.25 This was the last sighting of Douglass, east of Méry-la-Bataille, near Cuvilly.26 The record book remarks column states of him “not yet returned.” D1962 was “struck off charge” that day.

Douglass was initially listed as missing in action, and for about a year his family hoped that he might yet be alive.27 His comrades, however, were less sanguine. The entry for June 25, 1918, in War Birds reads in part: “I heard . . . that about fifteen of our boys have been killed. Hooper and Douglas [sic] are among them.” A little over a year after Douglass had failed to return from his mission with Baldwin, his family learned that his body had been recovered and buried by the French at Léglantiers, about halfway between Fouquerolles and Cuvilly. He was later reinterred at Villers-Tournelle, and then, finally, in the Somme American Cemetery near Bony, France.28

mrsmcq June 28, 2017. Revised May 1, 2019, to reflect No. 73 Squadron record book.

Photo at Ayr added August 1, 2019

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Douglass’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Charles William Harold Douglass. The photo is a detail from a group photo of Squadron 7 at the Ohio State University School of Military Aeronautics.

2 Information on Douglass’s family is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 See wedding announcement and obituary posted at ProgBase [pseud.] and Kathy Sloan, “William Arthur Douglass.”

4 “Flier Missing since June 11, Family Learns.”

5 Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917-1919, record for Charles William Harold Douglass; “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

6 Murton Campbell, diary entries for November 1 and 2, 1917.

7 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 14, 1917; Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917.

8 Murton Campbell, diary entry for November 19, 1917.

9 Milnor, diary entry for December 23, 1918; Murton Campbell, diary entry for December 28, 1917.

10 “War Materials from French Forests,” p. 76.

11 Cables 726-S and 1008-R.

11a Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.” Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917-1919, record for Charles William Harold Douglass, provides and active service date of April 6, 1918.

12 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of May 9, 1918.

13 See the relevant R.A.F. casualty forms: “Lieut. Charles William Harold Douglass,” “Lieut. Burr Watkin [sic] de Bassette Leyson USAS.,” and “Lieut. Richard Mortimer U. S. A. F. (USAS).”

14 “Lieut. Harold Clement Hayes RAF,” “2nd Lieut., Lieut. Thomas Geoffrey Drew Brook R. A. F General List,” and “2nd Lieut. Roland Dudley Doane RAF.”

15 Minterne, The History of 73 Squadron, p. 7.

16 On the locations of No. 73 Squadron, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 416.

17 On the role of IX Brigade, see Callender, War in an Open Cockpit, p. 57, note 3.

18 See RFC/RAF No. 73 Squadron Record Book. Unless otherwise noted, the subsequent description of 73 and Douglass’s activity is based on the record book. I should note that the copy of the record book I have been able to consult is of poor quality; I have done my best to decipher place names and plane numbers in particular, but may not always have been accurate.

19 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 35.

20 Heater, [Informal account], p. 125.

21 See the casualty card, “2nd Lieut., Lieut. Keith William Allardyce Symons.”

22 Probart’s last name has been mistranscribed from official R.A.F. records (service record, casualty form) as “Probert.” His middle name is sometimes spelled “a’Beckett”; see documents available at Ancestry.com and at Familysearch.org.

23 The War in the Air, vol. 6, pp. 403–04.

24 See the relevant entry in RFC/RAF No. 73 Squadron Combat Reports.

25 On von Beaulieu-Marconnay’s claim, see the entry in Franks, Bailey, and Duiven The Jasta War Chronology.

26 See also casualty card, “Douglass, C.W.H.”

27 “Lieut. Douglass Wounded” and “Brother of Mrs C. J. Wood Buried Overseas.”

28 “Brother of Mrs C. J. Wood Buried Overseas.” See Crowell and Wilson, Demobilization, pp. 83-91, on the location of isolated graves and reinterment in “concentration” cemeteries. For his final resting place in the Somme American Cemetery, see “Charles Wh [sic] Douglass”; the name on the grave marker is “Charles W.H. Douglass.” And see “Douglass, Charles W. H.”