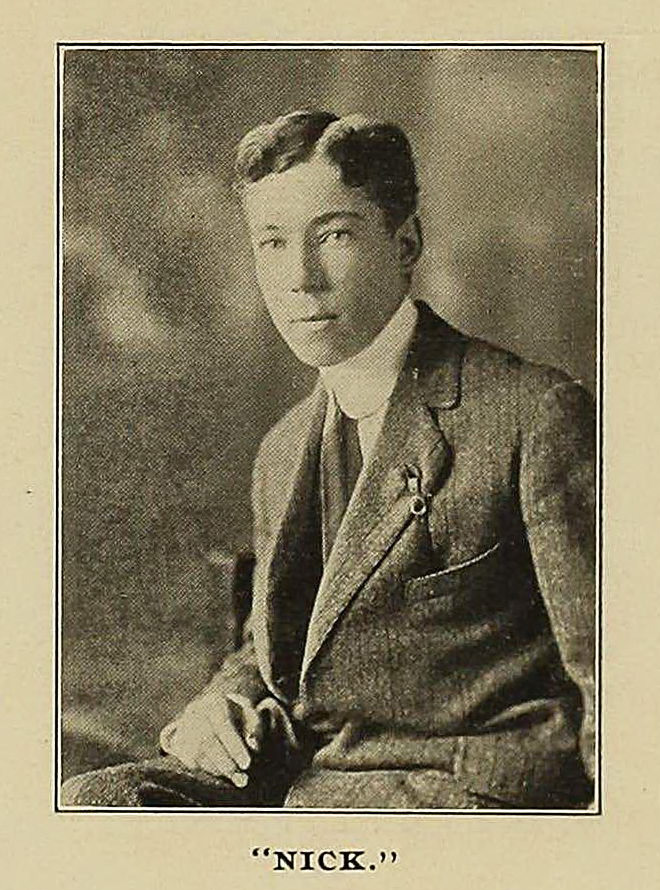

(Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, October 8, 1893 – Easton Aerodrome near Stamford, England, February 18, 1918).1

Nichol’s father, James Pollock Nichol, of Irish descent, was born in Philadelphia. He married Michigan-born Matie Louise Brockway in 1892, a few years before receiving his degree in dentistry from the University of Pennsylvania and establishing what would become a well-regarded practice in Philadelphia.2 Clark Brockway Nichol, an only child, attended Germantown Academy in northwest Philadelphia, graduating in 1911.3 He entered the University of Pennsylvania and studied mechanical engineering; he apparently left without receiving his degree.4 In 1916, at the time of the Mexican Expedition, Nichol served with Troop A of the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry, which was for a time stationed at El Paso, Texas. The following year, from May through early July, he was in the R.O.T.C. at Fort Niagara.5 He then transferred to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and attended ground school at Cornell’s School of Military Aeronautics, graduating September 1, 1917.6

Nichol, along with most of his ground school classmates—including fellow-Philadelphian Hilary Baker Rex, who had also been at Penn, Ft. Niagara, and Cornell—chose or was chosen to continue training in Italy and was thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed from New York for Europe on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania. After a brief stopover at Halifax the Carmania joined a convoy for the voyage across the Atlantic. The men sailed first class and enjoyed some leisure, including concerts featuring the violinist Albert Spalding, who was on board. They also had Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, and, once they entered dangerous waters, they took turns at submarine watch. When the ship docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment members learned that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England for their training. They travelled by train to Oxford, where they attended ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics. While at Oxford Nichol shared a room on the top floor of Christ Church College with Rex, Wilbur Carleton Suiter, and Richard Brumback Reed, all of whom had been in the same Cornell ground school class.6a

Early in November 1917, twenty members of the detachment were selected to begin flying training at Stamford in southwest Lincolnshire, while the remaining men, including Nichol, travelled farther north to Grantham to attend machine gun school at Harrowby Camp; they were in a holding pattern because there were not yet openings at training squadrons to accommodate them.

Nichol’s friend Rex noted in his diary on November 8, 1917, that at Grantham “They are treating us royally here. We have a mess of our own and the meals are better than those on the Carmania. The quarters are very comfortable. I am in what they call a ‘hut’ with seven other fellows.” Nichol was one of Rex’s “hut mates,” along with Wendell Ellison Borncamp, George Atherton Brader, Ralf Andrews Crookston, Burr Watkins Leyson, Donald Swett Poler, and Donald Andrew Wilson; Lloyd Ludwig joined them partway through the month.6b Fifty men were able to set off for training squadrons on November 19, 1917, but Nichol and Rex were among those who remained at Grantham through the end of November, which meant that when they finished their two weeks of training on the Vickers machine gun, they began two more on the Lewis. It also meant that they took part in the Thanksgiving festivities at Grantham on November 29, 1917, which included an American football game followed by a feast and partying well into the night. According to Rex, Nichol returned to their hut in the early hours of the following morning, “with an army composed of three English officers, which he proceeded to put through manoeuvres.”6c

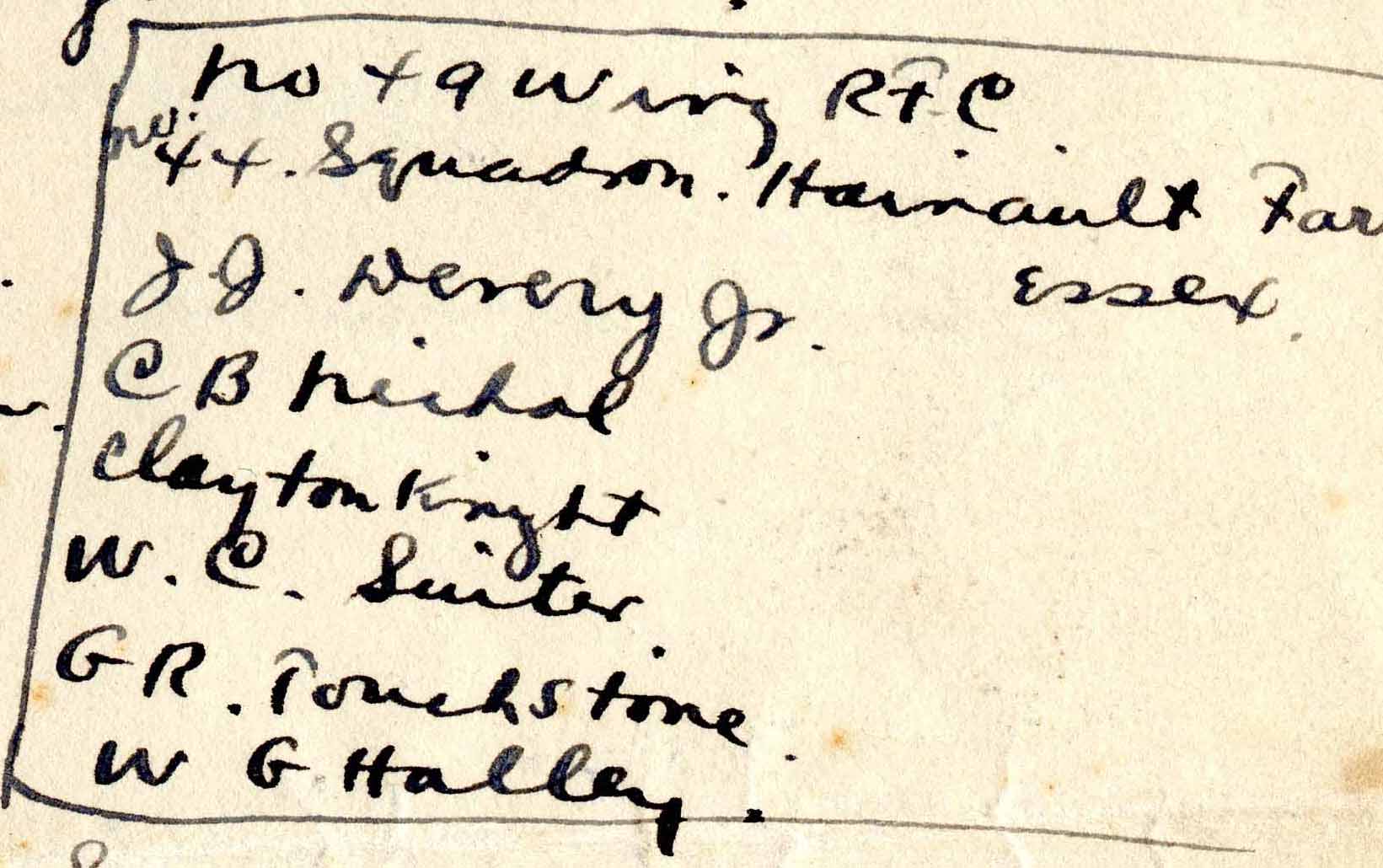

Finally, on December 3, 1917, all of the men still at Grantham were posted to flying squadrons. Nichol, along with his ground school classmates John Joseph Devery, Suiter, and Grady Russell Touchstone, as well as Walter Ferguson Halley and Clayton Joseph Knight, was assigned to No. 44 Squadron at Hainault Farm near Ilford on the northeastern outskirts of London.7 No. 44 was an operational rather than a training squadron, one of the home defense squadrons tasked with protecting London against German Zeppelins and Gothas. By 1918 the pilots of No. 44 were flying Sopwith Camels, some of which were adapted to night flying in response to German nighttime raids. Knight later recalled that “No. 44 Squadron was an eye-opener for all of us. There was absolutely no formality in the Mess, in contrast to our experiences at Oxford and Grantham, where military procedures were the stiffest we had met, and the Camels were a revelation of trimness and grace in the air.”8 Needless to say, the men did not receive instruction on Camels (single-seaters, notoriously difficult for inexperienced fliers). Instead, “The squadron’s pilots were supposed to teach us during quiet times when there were no enemy raids, and we were loaned a BE2c for that purpose.”9 The B.E.2c was a two-seater, originally designed for reconnaissance and bombing, but by this time obsolete.

Nichol made his first flight on December 8, 1917.10 After that there were “a number of interruptions in our training from a source other than marauding German night-bombers. 44 Squadron was often asked to perform exhibition flights in London.” Knight noted that Nichol was among those unhappy with the delays: “he wanted to get on with the war before it ended.”11

In January 1918, according to Knight, “we six Americans were posted away to a regular flying training unit at Stamford” and Rex, at 5 T.D.S. near Stamford, wrote in his diary at the end of the month that “Nick and Shorty Suiter and quite a few of the Italian Detachment have shown up here.”12

No. 5 T.D.S. had its aerodrome at Easton on the Hill, southwest of Stamford (the men from the detachment who had been sent to Stamford in mid-October went to No. 1 T.D.S. at nearby Wittering). Assuming Nichol’s experience was similar to Rex’s, he would have had about a week of ground instruction and then have gone up in a B.E.2e with an instructor, initially for “air experience,” and then dual, i.e., in a plane with controls for both pupil and instructor, with the instructor handing off control to him as desired. Despite frequent poor weather, by February 18, 1918, Nichol had gotten in just over five hours dual, and he was cleared to fly solo. He apparently made one successful short flight (five minutes), but when he went up again, in a B.E.2e (A8712), he overbanked on a right-hand turn, with disastrous results.13

Rex wrote in his diary on February 18, 1918: “Poor old Nick has gone west. Got into some sort of a spin to-day and dove straight into the ground from about 200 feet in a BE2e. He was smashed to pieces and the plane is a write-off.” Rex had the sad duty of writing to Nichol’s mother and, on February 21, 1918, he, along with Devery, Edward Carter Landon, Pryor Richardson Perkins, Suiter, and Albert Sidney Woolfolk, served as a pall bearer at Nichol’s funeral. According to Rex, Nichol was buried in the Stamford cemetery next to first Oxford detachment member Harold Ainsworth, who had been killed December 19, 1917, while flying at No. 1 T.D.S.14

In the summer of 1920, Nichol’s parents and a cousin, Samuel Fife Wilson, accompanied by Knight, travelled to England to visit his grave.15 In September of that same year Nichol’s body was returned to the U.S. and given a final resting place at West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd just outside of Philadelphia.16

mrsmcq January 19, 2021; revised May 2023 to reflect Rex’s diary

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Nichol’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Clark B Nichol. For his place and date of death, see “Nicholl [sic], C.B. (Clark B.).” The photo is taken from [University of Pennsylvania], Pennsylvania: A Record of the University’s Men in the Great War, p. [66].

2 Information on Nichol’s family is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com. On his father, see “Dr. James P. Nichol.”

3 Ye Primer 1911 Germantown Academy, p. 49.

4 University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania: a Record of the University’s Men in the Great War, p. 23, indicates Nichol was in the class of 1915. “Phila. Flyer Dies in Air Engagement” implies that Nichol cut short his studies in the spring of 1916 to go with the National Guard to the Mexican border. He is still listed as a student studying mechanical engineering on p. 623 of University of Pennsylvania, Catalogue of the University of Pennsylvania 1915–1916. Nichol’s name is not on the roster of graduates for either 1915 or 1916; see University of Pennsyalvania, Proceedings of Commencement June 16, 1915, and Proceedings of Commencement June 21, 1916.

5 See the “Veteran’s Compensation Application” in Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917–1919, 1934–1948, record for Clark B Nichol.

6 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917],” where he is listed as “Clark B. Nichols.”

6a Rex, World War I Diary, entry for October 3, 1917.

6b Ludwig, diary entry for November 19, 1917.

6c Rex, World War I Diary, entry for November 29, 1917.

7 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

8 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: Artist & Airman,” quoting Knight, p. 199.

9 Ibid., pp. 198–99.

10 Ibid., p. 201.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid., p. 203; Rex, World War I Diary, entry for January 30, 1918.

13 “Nicholl [sic], C.B. (Clark B.).” According to the War Birds entry for March 3, 1918, “Nichol was killed at Stamford on his first solo.” It may be that he had gone up and landed successfully and then immediately taken off again; a log book would probably record this as a single flight with multiple practice landings.

14 On Nichol’s funeral, see Rex, World War I Diary, entry for February 21, 1918. On his burial at Stamford, see “Nichol, Clark B.”

15 See Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925, records for Aumea [sic; sc. James] P Nichol and for Samuel Fife Wilson; Ancestry.com, UK, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960, record for Matie Nichol, where her name is preceded by that of her husband and followed by those of Clayton Knight and Samuel Wilson; and Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, record for James P Nichol, where his name is preceded by that of Samuel Fife Nichol and followed by those of Matie B Nichol and Clayton Knight.

16 See Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Clark B Nichol; Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, U.S., Veterans Burial Cards, 1777-2012, record for Clark Brockway Nichol.