(Rochester, New York, March 30, 1891 – Danbury, Connecticut, July 17, 1969).1

Training to fly in England ✯ Alquines, France, No. 206 Squadron ✯ October 5, 1918, raid on Courtrai ✯ After the war

Clayton Knight’s father, Frederick C. Knight, a dry goods merchant in Rochester, New York, was born in Canada, but the Knight family was a New York one.2 Knight’s grandfather, Cyrus Maxwell Knight, served with a New York regiment during the Civil War.3 As early as 1910, Knight started on a career as an artist, working as a designer for the Stecher Lithographic Company in Rochester.4 Soon thereafter he moved to Chicago to study at the Art Institute; he was among the winners there of the Frederick Magnus Brand prize for composition in 1913.5 He returned to New York and was residing in Manhattan and working as an artist when he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917. Later that month he was accepted into the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps.6 He attended ground school at the University of Texas, graduating August 25, 1917.7

There were about thirty-six men in Knight’s ground school class; ten chose or were chosen for training in Italy, and these ten were among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. The ship left New York September 18, 1917, made a stop at Halifax to join a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, and arrived at Liverpool October 2, 1917. There the men learned that they were not bound for Italy; they were instead ordered to Oxford to attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics. Various explanations have been offered for the change of plans.8 Whatever the reason, the men of the detachment fairly quickly made their peace with the situation and in retrospect recognized the benefit of R.F.C. training, despite the Oxford S.M.A.’s “apoplectic C.O.,” Colonel Beor.9

In early November about twenty men were selected by Elliott White Springs, who was in charge of the cadets, to begin flight training at Stamford. The remaining men, including Knight, were ordered to a machine gun school, Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire; there were not enough R.F.C. squadrons to accommodate all the Americans. After two weeks, fifty of these men, including Knight’s friend from ground school, Glenn Dickenson Wicks, were sent to various training squadrons, but Knight was among those who remained at Grantham and completed the four-week machine gun course. 10 When Thanksgiving came, the men celebrated in grand style, and a number of those already at training squadrons returned to Grantham for the day. Festivities included a football game between the “Unfits” and the “Hardly Ables.”11 Knight kept a photograph of the victorious Unfits.12

Training to fly in England: Hainault Farm, Stamford, Thetford, Marske

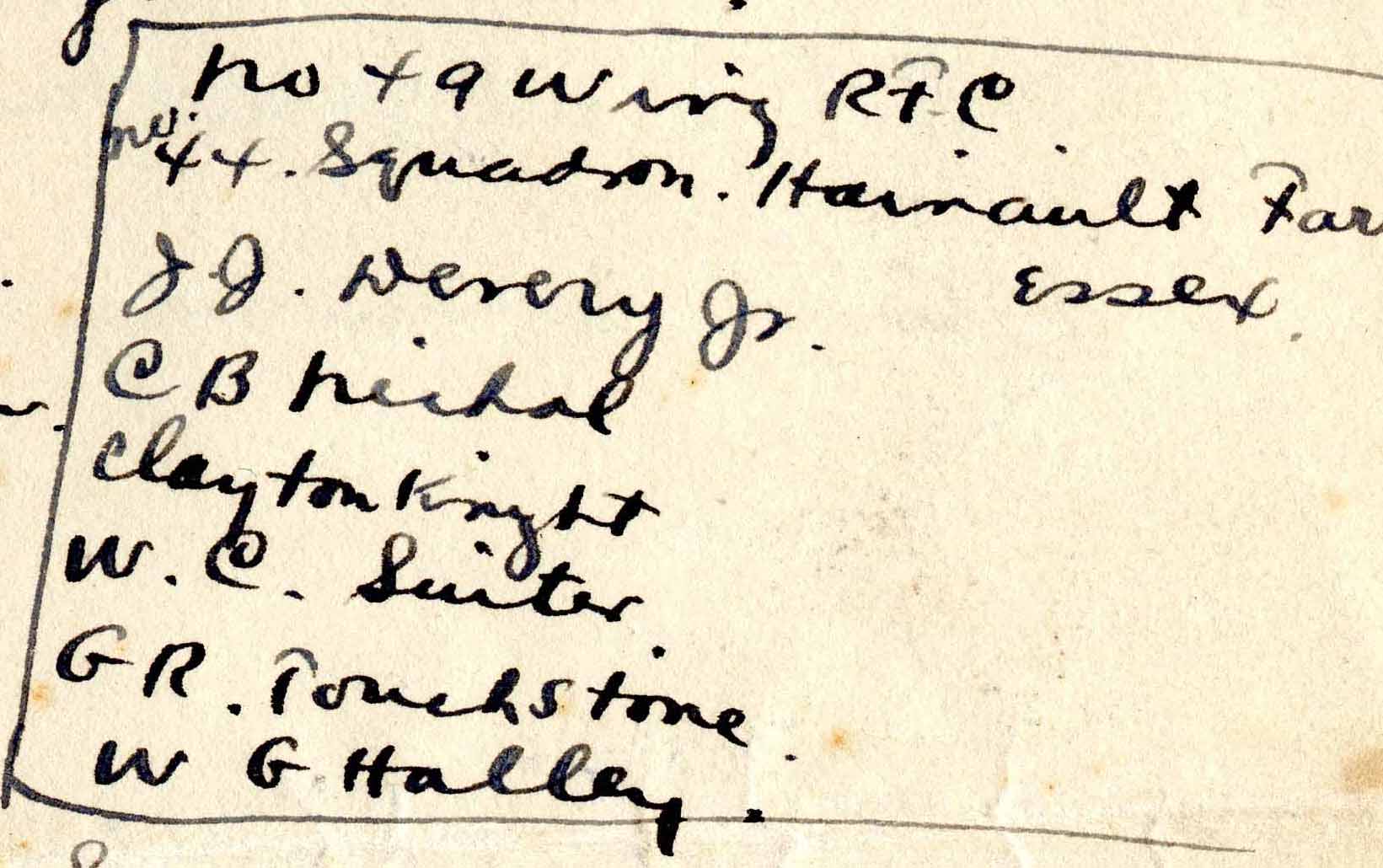

A few days later, on December 3, 1917, all of the men still at Grantham were posted to flying squadrons. Knight, along with his ground school classmates John Joseph Devery, Wilbur Carleton Suiter, and Grady Russell Touchstone, as well as Walter Ferguson Halley and Clark Brockway Nichol, was assigned to No. 44 Squadron at Hainault Farm near Ilford on the northeastern outskirts of London.13 While some of the other men had been assigned to training squadrons, No. 44 was operational, a home defense squadron tasked with protecting London against German Zeppelins and Gothas. By 1918 the pilots of No. 44 were flying Sopwith Camels, some of which were adapted to night flying in response to German nighttime raids. Knight later recalled that “No. 44 Squadron was an eye-opener for all of us. There was absolutely no formality in the Mess, in contrast to our experiences at Oxford and Grantham, where military procedures were the stiffest we had met, and the Camels were a revelation of trimness and grace in the air.”14 Needless to say, the men did not receive instruction on Camels (single-seaters, notoriously difficult for inexperienced fliers). Instead, “The squadron’s pilots were supposed to teach us during quiet times when there were no enemy raids, and we were loaned a BE2c for that purpose.”15 The B.E.2c was a two-seater, originally designed for reconnaissance and bombing, but by this time obsolete. Knight flew for the first time on December 8, 1917, with South African pilot D’Urban Victor Armstrong as his instructor; as he continued his training he also flew with Christopher Joseph Quinton Brand, also from South Africa. Knight later recalled that at 44 squadron “we learned all the fundamentals of flying, but aside from hangar tales, air fighting was not covered. 44’s techniques were different and exploratory in contrast to daylight fighting.”16

In January 1918 Knight was posted to Stamford,16a almost certainly, like his fellow second Oxford detachment members John Marion Goad, John Warren Leach, Robert Thomas Palmer, and Pryor Richardson Perkins, to No. 5 Training Depot Squadron at Easton on the Hill about two miles south-southwest of Stamford (the second Oxford detachment members sent to Stamford in early November had been assigned to No. 1 T.D.S. about three miles to the east, near Wittering). At 5 T.D.S. Knight would have trained initially on B.E.2d’s and B.E.2e’s and then perhaps DH.6s. The rate at which men of the second Oxford detachment were able to progress in their training varied widely, depending on the availability of instructional planes and instructors, on the weather, and on bureaucracy. While Goad and Leach completed their training and tests at Stamford by the end of February 1918, Knight’s progress (and Palmer’s and Perkins’s) was considerably slower. In March 1918 Knight wrote his sister that “I have two more types of machines to learn to fly on before I’ll be ready for overseas—and several tests. . . . We have to pass all the Royal Flying Corps tests. Do long cross country flights with landings at other aerodromes—do bombing, take photographs—flight tests and finish up on service machines used at the Front.”17 But, finally, on May 19, 1918, Knight “went solo on R.E.8s and flew one nearly three hours, made four landings, climbed to 8,000 feet, and used my vacuum control, which makes me a graduate according to the RAF regulations.”18

A few days prior to this, Knight’s name was among those listed in a cablegram from Washington confirming their status as “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying.” Earlier in the year it had been brought to General Pershing’s attention that many cadets like Knight had been held up in their progress towards commissions by the limited training facilities. On March 13, 1918, Pershing had cabled to Washington requesting permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .”19 Washington approved the plan in a cable dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.”20 Thus on April 8, 1918, Pershing had recommended Knight along with many other second Oxford detachment members for their commissions as first lieutenants “Aviation Reserve non flying.”21 It took over a month and some prodding, but finally, on May 13, 1918, Washington cabled back approval.22 The news would have reached Knight just about the time he went solo on the R.E.8, and presumably the paperwork was soon completed transferring him from reserve, non-flying to flying status. He was placed on active duty status on May 29, 1918.23

Knight celebrated his commission and his graduation with a trip to Nottingham with his friend Hilary Baker Rex.23a The two second Oxford detachment members had gotten to know one another well during their time at Stamford. Rex noted in his diary on March 21, 1918, that “The more I see of Clayton Knight the better I like him. I didn’t like him at all at first.” After putting up with poor accommodations for a time at 5 T.D.S., the two were able to get “a room together at the baths”—this was The Baths at 16 Bath Row, the home and business establishment of Mrs. Ingle in Stamford. “We get along very well and the Ingles are very good to us. They let us have a fire whenever we want it and hot water and baths are free.”23b

In late May 1918 Knight was transferred from Stamford to Thetford, about fifty miles to the east, in Norfolk. That he went, at least initially, to No. 128 Squadron rather than the newly formed No. 35 Training Depot Station at Thetford is suggested by a remark made by Charles Carvel Fleet in a letter to Leslie Alfred Benson: “I suppose you know Bill [Mooney], Mac [Maloney], [Robert] Palmer & Knight have gone to 128 T.S. Thetford”—Fleet was mistaken in assuming No. 128 was a training squadron.23c Once at Thetford, Knight may have been reassigned to No. 35 T.D.S. Knight noted that after Stamford he and William Henley Mooney trained together, and Mooney’s R.A.F. service record indicates he was at No. 35 T.D.S.23d In any case, at Thetford, Knight trained on DH.9s, the bomber that he later flew operationally.23e Rex, now (mid-June) at Wyton and about to go to Marske, spent part of his last week at Wyton “ferrying busses between [Wyton] and Thetford. Saw Clayton Knight twice. Wish he was going to Marske with me.”23f Knight did go to the No. 2 Fighting School at Marske-by-the-Sea on the Yorkshire coast, but not until late July 1918, by which time Rex was in France. 24

Alquines, France, No. 206 Squadron

Finally, at the end of August, Knight learned that he was to go to France.24a He and William Henry Mooney, a friend of his from the second Oxford detachment with whom he had trained since Stamford, went to London to pick up their orders, wangled a two-day leave, and then set out from Waterloo Station for the coast. They crossed the Channel on a destroyer. At the pilot’s pool in France, they got their squadron postings: Mooney to No. 211 Squadron R.A.F., and Knight to No. 206.25 206, a DH.9 squadron, was stationed at Alquines—about fifteen miles south-southeast of Calais and about the same distance east of Boulogne. In a letter home written shortly after his arrival at Alquines, Knight described how “The collection of tents and huts where we live and eat straggle down the side of a slope looking over an immense valley with rolling hills patched everywhere with fields of oats and wheat, clover and freshly ploughed land.”26 Knight was the fifth American, and the fifth member of the second Oxford detachment, to be posted to 206. Harry Adam Schlotzhauer, Hugh Douglas Stier, John Warren Leach, and Galloway Grinnell Cheston had joined the squadron at the end of May. Leach had been wounded and sent home in June; Cheston was killed in action in late July. Stier and Schlotzhauer were still with the squadron when Knight arrived.27

206 was part of the 11th (Army) Wing of the R.A.F. on the British Second Army’s front and was tasked with patrolling that front, which ran for about thirty miles from (approximately) Diksmuide south past Ypres to Armentières. Starting August 8, 1918, successful Allied offensives were carried out at various points along the Western Front, keeping the German armies off balance, but all of these took place to the south of the Second Army’s section of the front, which, on the ground, was quiet. However, as 206 Squadron observer John Stephen Blanford noted, in September 1918 “There were various indications that our turn to attack must come soon. One pointer to this was the concentration of our bombing raids on the big enemy ammunition dumps in the Courtrai [Kortrijk] area.”28 As well as making bombing raids, 206 undertook extensive reconnaissance and photographic missions of German occupied Belgium.

On arriving at No. 206 Knight joined B flight and was assigned an observer, John Hubert Perring. Perring, born near Cardiff in about 1888, had been serving in the British military since the end of July 1915, initially apparently with an infantry regiment (Welsh Regiment) and then in the Royal Army Medical Corps.29 He transferred to the R.A.F. and began his instruction in aerial observation towards the end of June 1918. He was assigned to the B.E.F. on August 28, 1918, as a day-bombing observer; he arrived at No. 206 around the same time as Knight.30 A photo of B flight from September 1918 in Blanford’s “Sans Escort” (pt. 1, p. 154) includes Knight and Perring.

Knight had a very brief period of orientation with 206 before making his first line patrol, probably on September 6, 1918, when he was tasked with escorting Leslie Reginald Warren’s plane.31 Knight wrote home:

I feel so much better since I began to “pay off the mortgage.” My first trip over the lines was chiefly a job of getting information and also as a protection to another pilot and observer who were on a reconnaissance. We flew low over the lines. I was at one side and slightly higher than he and could watch his observer leaning over the side of the machine, muffled up like a huge monkey, peering down into those trenches and shell holes, along roads and railroad, for any sign of movement. Our job was to relieve him of any necessity for keeping a lookout above and my observer with his machine gun swinging loosely on its mounting kept a lookout behind. We were fired at from the ground at a couple of places—the “wumph” of “archie” followed by the little ball of black smoke hanging in the air some distance away: none came near us this time. We probably covered twenty-five miles of the line, and then swung away and came home, with the report of movement and fires burning behind his front, showing perhaps a preparation for retreat.32

On September 7, 1918:

loaded with bombs, a whole formation of us climbed high up and, keeping as close together as possible, crossed over and made for an important railroad center back of his lines. Being a new hand at the game, I wasn’t sure when we crossed till the “archie” began bursting all about us. . . . Very quickly, it seemed to me, the signal from the leader came. I turned in my seat to poke the observer, who stood with his gun watching for Huns, and he ducked down in his seat to release the bombs. The ones on the other machines seemed to detach themselves at the same time and fell away from us. The whole formation swung about and we started for home like a flock of scared kids who [had] just broken a window and were being chased. The fellow just ahead of me had his radiator hit by a piece of shell, and, as the water went out, soon a trail of steam showed and he kept sinking gradually under and I moved up in his place. He was high enough and glided over past the lines and landed safely. Back we came, and I had struck my first blow.33

This was probably the bombing mission targetting Quesnoy (presumably Quesnoy-sur-Deûle) that Blanford recalled taking part in that day.34

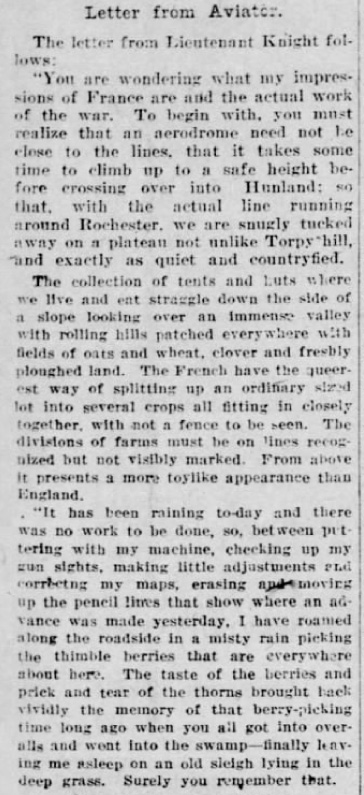

For the next week the weather was such that the squadron could not fly their usual dawn and dusk reconnaissance flights and daily or twice daily bombing raids. In his letter home, Knight remarked that “It has been raining to-day and there was no work to be done, so, between puttering with my machine, checking up my gun sights, making little adjustments and correcting my maps, erasing and moving up the pencil lines that show where an advance was made yesterday, I have roamed along the roadside in a misty rain picking the thimble berries that are everywhere about here.”35 The evening of September 11, 1918, was memorable for a farewell party for Stier and Schlotzhauer, who were leaving the squadron the next day.36 This left Knight the only American in the squadron.

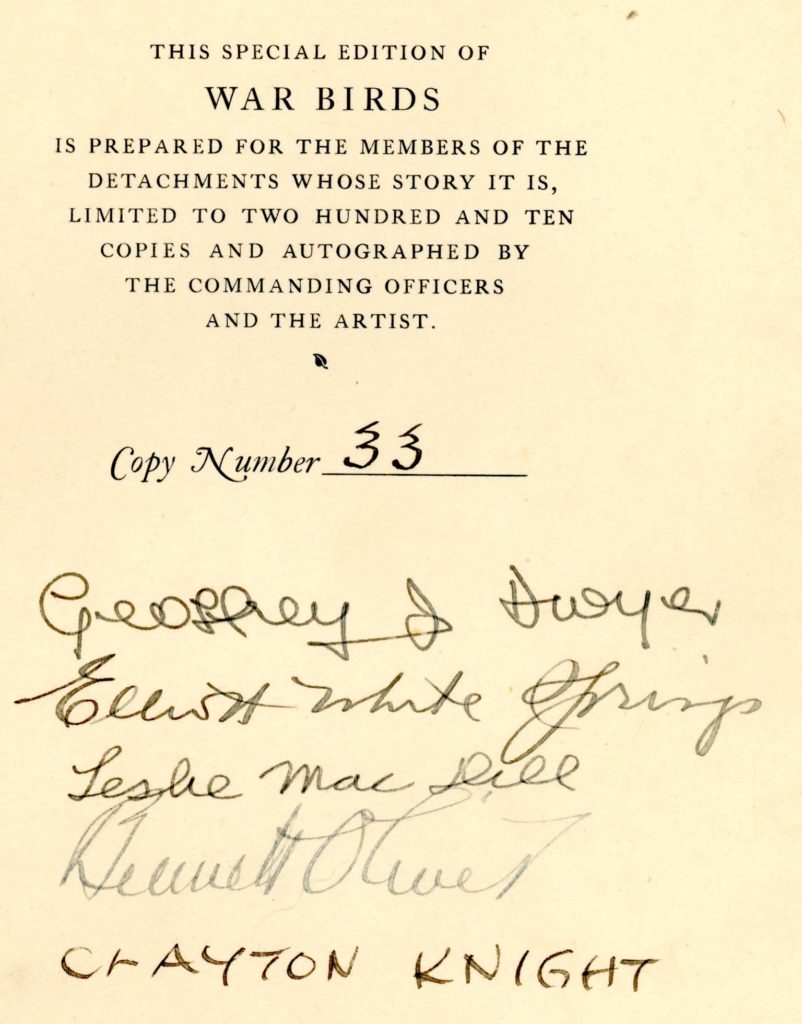

There is a passage in War Birds that, if the incident isn’t entirely fictional, may point to a visit by Springs to No. 206 Squadron, perhaps during this period of bad weather—and that adumbrates the later collaboration of the writer and the artist: “I was over at a Nine squadron the other day and saw Clayton Knight. He showed me some sketches he had made of planes and fights. They were very good. That boy will be an artist some day if he lives thru it.” This is from the War Bird entry for August 17, 1918, well before Knight was at 206, but the preceding paragraph records Cheston’s death, and this may have led Springs to slot in another incident relating to DH.9s and 206 Squadron at this point. There is no mention of Knight in Springs’s letters, but Springs does refer to much socializing with other squadrons around September 12, 1918, although typically with ones somewhat closer than the forty miles from Remaisnil (where the U.S. 148th Aero Squadron was stationed) to Alquines.37

By mid-month the weather had improved dramatically, and on September 16, 1918, flying was resumed.38 Although Knight probably participated in reconnaissance and bombing missions during the period from September 16–20, it was not until September 21, 1918, that he took part in one that left a paper trail that I have been able to find. Blanford recalled an accident on that day: B and C flights were setting out to bomb an ammunition dump at Bissegem, a village just west of Courtrai, when Knight had engine trouble and was forced to turn back. As he attempted to land, his wing touched the ground and the plane cartwheeled and crashed—with serious damage to the plane but not the crew.39 Ray Sturtivant and Gordon Page’s compilation of incidents relating to D.H.9s includes one involving Knight and Perring taking off in D5750 in a cross wind, and crashing; the men were unhurt, but the plane was sent the next day to a repair park. Sturtivant and Page give the date September 20, 1918, for the incident, but the log book of C flight pilot Edward Trevor Evans shows a raid on Bissegem on the 21st, suggesting that Blanford’s recollection of September 21 is correct and that Sturtivant and Page for some reason recorded the wrong date.40 Knight, apparently without noting the date, recollected a crash shortly after take off involving a cross wind and an unresponsive engine, and all these accounts are presumably of the same incident.41 Blanford indicates that “Knight and Perring were flying again a day or two later, in a new aircraft.”42 However, the replacement plane was not satisfactory, despite the efforts of mechanics to tune up the engine after every flight.43

On September 26, 1918, C flight pilot Evans wrote his mother that “We are expecting to be very busy here and very shortly, on low flying work: i.e. strafing the hun with bombs and machine gun fire from a low altitude. Cannot or rather must not say any more.”44 And, indeed, on September 28, 1918, General Sir Herbert Plumer’s Second Army, in concert with the Belgian army and some French divisions, launched an offensive in Flanders that in one day retook the entire area so bitterly fought over during the three months of the Battle of Passchendaele the preceding year. The inability of German forces to respond can in part be attributed to the work of photo-reconnaissance squadrons like 206, thanks to which “most of the German gun batteries had been successfully identified and silenced.”45 The raids on ammunition dumps similarly helped cripple German response, as did a raid carried out by 206 on September 29, 1918, on the railway station at Menin (Menen).

Weather on September 28, 1918, was bad, and there was limited flying.46 The skies had cleared by the next morning, September 29, 1918, “which was to prove one of 206’s busiest and most memorable days.”47 In addition to dawn reconnaissance, 206 undertook a morning raid on Halluin (just south of Menin) before the weather started closing in again in the afternoon. “However, about 5.00 pm we received orders from 11 Wing to bomb Menin Station despite the weather, as some of our fighters . . . reported heavy German reinforcements, . . . detraining at Menin, and it was expected they were preparing a counter-attack.” Rather than flying to the target as a formation, it was agreed that “all our available aircraft (15)” would take off successively at short intervals and one after another bomb and strafe the Menin train station.48 The fifteen aircraft that took part in this operation—three short of the eighteen that would be needed for the normal six teams in each of three flights—probably included one piloted by Knight, presumably the DH.9 whose engine was giving intermittent trouble. Blanford recalled that “we had carried out a highly successful attack, and we learned the next day that we had so disrupted the detrainment and deployment of the German division that the expected counter-attack never materialized. The 2nd Army captured Menin a day or two later.”49 By October 2, 1918, the advancing Allied troops had outrun their supply lines, and the offensive on the ground in Flanders came to a halt.

Attacks from the air were, however, still very much on the agenda. The morning of October 4, 1918, Knight’s B flight set out on yet another raid on the ammunition dump at Bissegem. Knight, flying with Perring, had engine trouble and turned back to land at an airfield at St. Omer, about eleven miles east of Alquines. There it was determined that the engine was beyond repair.50

October 5, 1918, raid on Courtrai

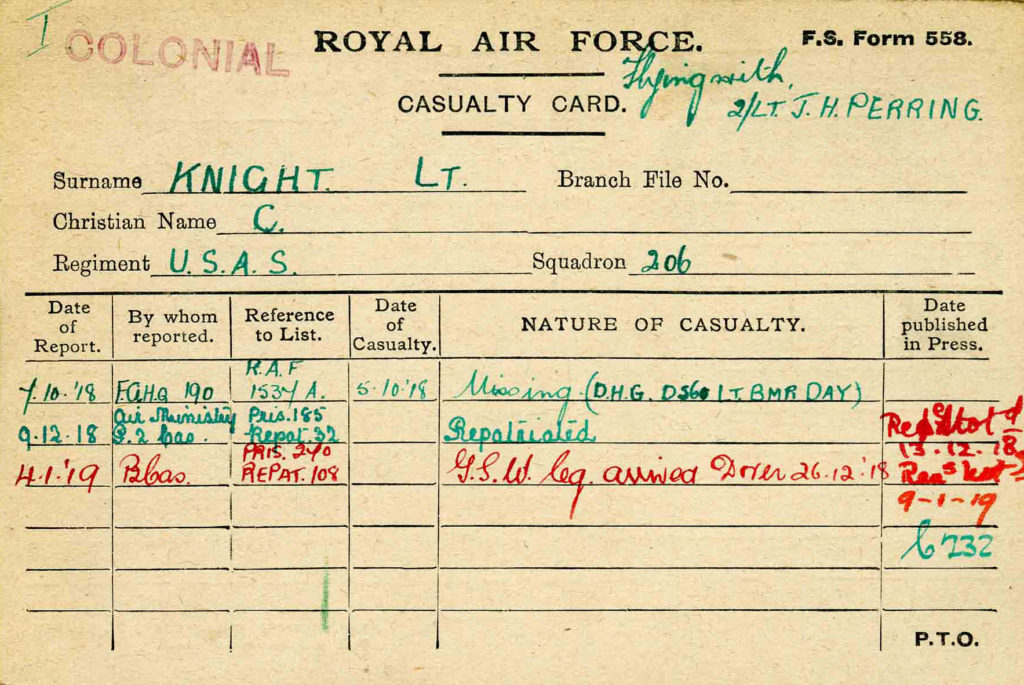

The next day, Knight was assigned DH.9 D560. The plan that day, October 5, 1918, was for two formations of five planes each to make an early morning bombing raid on Courtrai and then to land at their new airdrome at Sainte-Marie-Cappel, about twenty-two miles east of Alquines, and thus closer to where the front lines were in the aftermath of the recent offensive.

Blanford, who was flying as observer in the lead plane piloted by Rupert Norman Gould Atkinson, has provided a detailed account of the Courtrai raid, “the Squadron’s unluckiest day of the war.”51 On earlier raids on Bissegem and Courtrai, 206’s planes had climbed up to about 14,000 feet, flying essentially due east directly to the target and back. On the 5th, however, they were to fly to the north and beyond Courtrai before turning south and then back west “so that we should be on the homeward run when we dropped our bombs, attacking the target from the rear for a change.”52 Further raids were planned that day, so they were to save time by climbing “only” to 10,000 feet and, bombs dropped, to head to the new aerodrome noses down quam celerrime in order to escape the anticipated heavy anti-aircraft fire.

The lead formation, with pilots Atkinson, Evans, Charles Linnaeus Cumming, Herbert Leslie Prime, and Peter George Addie, flew north, made their turn, and dropped their bombs amid heavy and effective ground fire.53 The rear formation was made up of planes from B flight, whose pilots—Harold William Campbell, Hugh McLean, Herbert Alfred Denny, Knight, and Gilmour Ian Packman—were all experienced; none of them, however, had led a formation before. This rear formation apparently swung too wide on their turn back towards Courtrai. Blanford, once he had dropped his bombs, “looked astern again to see how our rear formation was faring. They should have been closed up about 100 yards behind us, but to my dismay I saw they were at least 400 yards astern, and not only that, there were at least a dozen Fokker DVIIs beginning to dive on them from the south east and about 1,000 feet higher.”54 The lead formation reduced speed (“we became sitting ducks for the German gunners”) to allow the rear formation to catch up.55 Knight, flying in the rear of his formation, recalled later that his engine had “started to play up during the turn before the bombing run, and his aircraft quickly dropped behind and lost altitude.”56 “When the Fokkers attacked, the two leading ones cut him off and he was last seen going down with them on his tail.”57 “The remaining four aircraft of B flight succeeded in keeping their formation intact, dropping their bombs and all getting back to our lines, despite persistent attacks by at least 10 Fokkers.”58

Six of the ten planes that had set out on the raid on October 5, 1918, returned largely unscathed. Of the other four, two crash landed in friendly territory.59 Atkinson and Blanford came down near Ypres without injury to themselves. Similarly Packman, whose radiator had been hit, crash landed just west of Ypres. His observer, [probably James Harold Kennedy, not J. W.] Kennedy, was uninjured; Packman was hurt, but apparently not seriously.60 Two planes went down in German-occupied Belgium. Knight and Perring came down near Courtrai. Prime’s plane was hit, and he was severely injured; his observer Cyril Hancock “managed to glide down, using his dual control, and made a crashlanding from which Prime and he escaped with their lives.”61 Both men became prisoners of war; Prime subsequently died of his wounds.

Knight and Perring had been easy game for the enemy Fokkers, particularly once the rest of the squadron had disappeared west. Their DH.9 was hit by machine gun fire and spun down out of control several thousand feet; the Fokkers were still attacking when Knight brought it out of its spin. After leveling out, Knight was able to fire at and hit a Fokker that was coming at him straight on before it ducked beneath him. Wounded, and with a damaged plane, he nonetheless managed to make a forced landing near Aelbeeke (Aalbeke), about three miles southwest of Courtrai; the plane flipped over. Perring attempted to burn the DH.9 rather than having it fall into enemy hands, but it apparently no longer had enough fuel for a fire. It became evident that Knight’s wound was serious. German soldiers took charge of the two men, escorting them to a German command post located on the first floor of a Belgian house where Knight’s wound received initial attention from a Belgian civilian doctor. Not long thereafter, Knight and Perring were separated. Later an ambulance took Knight, as well as Prime and Hancock to a hospital in Courtrai—Hancock, whose medical exam in early 1918 included the annotation “oversmoking,” smoked “nearly all my cigarettes during the trip.”62

From a hospital in Courtrai, Knight was transferred—presumably as part of the German retreat as the front moved east—to one at Deinze, about fifteen miles to the northeast of Courtrai. The Battle of Courtrai, in which the Second Army played a major role, commenced on October 14, 1918. Ammunition dumps and a railroad bridge in Deinze were targets. R.A.F. pilot Knight found himself less than popular with some of his fellow patients who were bomb victims.63 Before long “The town was so heavily bombed the hospital was evacuated and we went by barge to Ghents [sic]. We spent two days there, as the Allied Armies were rumored to be very close; thence by train to Antwerp where I spent about a month, still receiving the same treatment as their [the Germans’] own wounded. After the Armistice was signed, the Germans still insisted on taking us to Germany, but the Belgium Red Cross intervened and we were left in their charge. Later English motor ambulances took us to Brussels and Tournai.”64 Knight recorded that “The treatment accorded me as a prisoner of war was as satisfactory as conditions would permit.”65

Knight arrived in Dover the day after Christmas. Early in the new year, he was among a detachment of sick and wounded from the American Red Cross Hospital # 4 at Liverpool who sailed to the U.S. on the S.S. Caronia. The ship left Liverpool on January 14, 1919, made a stop at Brest, France, and arrived in New York on January 25, 1919.66

After the war

In the summer of 1920 Knight returned to Europe. His passport indicates plans to visit England, Belgium, and France for the purpose of “Business,” but the trip was evidently also personal: he travelled in the company of Mr. and Mrs. James P. Nichol and Samuel Fife Wilson, the parents and cousin of his fellow Oxford detachment member Clark Brockway Nichol, with whom he had trained at Hainault Farm and Stamford.66a Nichol had died in a crash near Stamford in February 1918, and his parents and cousin wished to visit his grave.66b

Knight resumed his work as an artist. In 1926 Springs’s War Birds, with Knight’s illustrations, was published. The following year Floyd Phillips Gibbons published an account of Manfred von Richthofen (The Red Knight of Germany), also illustrated by Knight. It was almost certainly Gibbons who initially discovered the identity of Knight’s opponent on October 5, 1918. Blanford, who stayed in touch with Knight, wrote that

in the 1920s a friend of [Knight’s], who was engaged in writing a book about Baron von Richthofen, was given permission by the Germans to inspect their Air Force records and combat reports. He took this opportunity to enquire about the combat in which Knight had been shot down, and found out that his opponent had been an Oberleutnant Harald Auffarth, leader of the Jagdstaffel concerned, and copied out the latter’s combat report, which reads as follows: “On October 5, 1918, I shot down a DH9 (British squadron 206, No. D560) out of a formation of 10 units and forced it to land near Aelbeeke, Belgium. Aircraft destroyed, pilot wounded, observer uninjured.”67

Eduard Florus Harald Auffarth had been for some time the leader of Jagdstaffel (fighter squadron) 29, and had recently been put in command of Jagdgruppe 3 (which was a grouping of four fighter squadrons, including Jasta 29). Auffarth was long since an ace, with twenty-two confirmed claims. Knight’s friend and biographer Peter Kilduff much later learned that Knight had badly damaged Auffarth’s plane and wounded Auffarth, though not seriously.68 The much-decorated German pilot went on to score further victories.

Just prior to and during the early years of World War II, Knight worked with Canadian ace Billy Bishop to recruit American aviators and aviation instructors to assist the buildup of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The effort, which went by the name “The Clayton Knight Committee,” was successful, but required considerable finesse, given American neutrality prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

mrsmcq September 4, 2018; July 20, 2021, section on Stamford revised to reflect information on 5 T.D.S.; May 2023 to reflect Rex’s diary

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Knight’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Clayton Knight. For his place and date of death, see “Aviation Artist, Clayton Knight Dies in Danbury.” The picture is the one used to illustrate the newspaper article “How Bombs are Dropped.”

2 See Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Fred K [sic] Knight, and family. The middle name “Clayton” for Clayton Knight’s father is supplied by Kinsman, ed., Contemporary Authors, vol. 1, p. 352.

3 Ancestry.com, New York, Town Clerks’ Registers of Men Who Served in the Civil War, ca 1861-1865, record for Cyrus Maxwell Knight.

4 See the 1910 census record for the Knight family cited above, and “How Bombs are Dropped.”

5 “Institute has Largest Art School Enrollment.”

6 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF,” p. 165.

7 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

8 See, for example, the explanations supplied by Hamilton Hadley on p. 4 (286) of “Foreign Aviation Detachments,” by Geoffrey Dwyer on p. 2 of “Report on Air Service Flying Training Department in England,” and by Claude E. Duncan as recorded in Sloan and Hocutt, “The Real Italian Detachment,” p. 44.

9 Kilduff had access to Knight’s diary and cites from it regarding the C.O. on p. 167 of “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF.” See the War Birds entry for October 22, 1917, regarding “the Colonel’s” effort to impose discipline on the Oxford detachment men; see Foss, Diary, entry for October 20, 1918, for another account, in which Colonel [Bertram Richard White] Beor is identified.

10 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF,” p. 167.

11 Chalaire, “Thanksgiving Day with the Aviators Abroad.”

12 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF,” p. 166.

13 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

14 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF,” quoting Knight, p. 168.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid., p. 171.

16a Ibid.

17 Ibid., p. 172.

18 Ibid., p. 173.

19 Cablegram 726-S.

20 Cablegram 955-R.

21 Cablegram 874-S.

22 Cablegram 1303-R.

23 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

23a Rex, World War I Diary, entry for May 27, 1918.

23b Rex, World War I Diary, entry for April 15, 1918.

23c Letter from Fleet to Benson dated May 31 [1918] in the Leslie A. A. Benson Collection, 1917-1919.

23d Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: Artist & Airman,” p. 206; The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for W Henley Mooney.

23e Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: Artist & Airman,” p. 206.

23f Rex, World War I Diary, entry for June 16, 1918.

24 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: Artist & Airman,” p. 206. Mooney was posted to Marske on July 24, 1918 (see preceding note). See Jefford, Observers and Navigators, p. 51, on the changing names for the school at Marske.

24a There is a puzzling reference to Clayton Knight in the July 11, 1918, diary entry of Leonard Atwood Richardson. Richardson, a pilot with No. 74 Squadron R.A.F., stationed at Senlis-le-Sec, wrote “Clayton Knight and Kuhlberg [sic; sc. Kullberg] of #1 come to #74 for dinner.” Richardson would not be the first to confuse Clayton and Duerson Knight—the latter was at No. 1 Squadron from mid-May until the first part of September 1918. However, Richardson goes on: “Knight is a fine artist and has many aerial drawings.” The most likely explanation is still that Richardson mixed up Clayton and Duerson, but it is remotely possible that Clayton Knight was in France on a ferrying job at this date, well before his actual posting to France. See Richardson, Pilot’s Log, p. 214.

25 Ibid. pp. 173–74.

26 Knight’s letter home is quoted in “How Bombs are Dropped”; no date for the letter is provided, but internal evidence indicates a date of September 8, 1918.

27 Knight recollected there having been six Americans at 206 besides himself (see p. 174 of Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF”). I have only been able to trace the four. It is possible Knight misremembered, but given the paucity of documentation regarding 206, it is equally possible that there were two others I have not found.

28 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 153.

29 Perring’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, 1911 Wales Census, record for John Hubert Perring. On his military service, see Ancestry.com, British Army WWI Medal Rolls Index Cards, 1914-1920, record for J. H. Perring.

30 On Perring’s service with the R.A.F., see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for John Hubert Perring.

31 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF,” p. 176.

32 Letter reproduced in “How Bombs are Dropped.”

33 Ibid.

34 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 153.

35 Letter reproduced in “How Bombs are Dropped.”

36 See Evans’s letter of September 12, 1918, reproduced at “With Fondest Love, Trev.”

37 See Springs, Letters from a War Bird, letters of September 10 and 12, 1918 (pp. 227–28).

38 See Evans’s log book entries, reproduced on p. 155 of “With Fondest Love, Trev” and Evans’s letter of September 17, 1918.

39 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 154.

40 Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File, p. 186. Evans’s log book entry is reproduced on p. 155 of “With Fondest Love, Trev.”

41 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF,” p. 177.

42 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 154.

43 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF,” p. 177.

44 See “With Fondest Love, Trev.”

45 Hart, The Last Battle, p. 126.

46 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 154, indicates that the weather “prevented our carrying out any raids.” Evans’s log book, however, shows an afternoon raid with bombs dropped on Comines (“With Fondest Love, Trev,” p. 157).

47 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 154.

48 Ibid., p. 155. Hart, on p. 129 of The Last Battle, cites a long passage about this raid from Blanford’s typescript of “Sans Escort” in the Imperial War Museum and indicates that the raid took place on September 28, 1918. An entry in Evans’s log book (“With Fondest Love, Trev,” p. 157) corroborates the September 29, 1918, date in the published version of “Sans Escort.”

49 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 156.

50 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF,” pp. 177–78.

51 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 157.

52 Ibid., p. 158.

53 Blanford refers consistently to a “J. S. Cumming” as a pilot with whom he flew. There was also in the squadron a “J[ohn] S[tevenson] Common,” and the similarity of last name may have led Blanford to refer to Canadian C[harles] L[innaeus] Cumming as J. S. Cumming.

54 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 159.

55 Ibid.

56 Ibid., p. 161.

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid.

59 See the relevant entries in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II.

60 Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield, and Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File, working with original documentation to which I have not had access, identify Packman’s observer as “J. W. Kennedy.” It is probable, however, that he was James Harold Kennedy, who is documented as having served with No. 206 Squadron; see “Lieut. J H Kennedy R A F.” Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 10, records Packman taking part in a mission again at the end of October 1918.

61 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 161.

62 See the accounts provided by Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 161, and by Knight as recorded by Kilduff on pp. 181–83 of “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF”; the quotation is from p. 183. On Hancock, see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Cyril Hancock.

63 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF,” p. 183.

64 From Knight’s account on p. 173 of Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany

65 Ibid.

66 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General. Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for detachment of sick and wounded . . . on S. S. Caronia.

66a See Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925, record for Clayton Knight; Ancestry.com, UK, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960, record for Matie Nichol, where her name is preceded by that of her husband and followed by those of Clayton Knight and Samuel Wilson; and Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, record for James P Nichol, where his name is preceded by that of Samuel Fife Nichol and followed by those of Matie B Nichol and Clayton Knight.

66b See Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925, records for Aumea [sic; sc. James] P Nichol and Samuel Fife Wilson.

67 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” p. 161.

68 Ibid., p. 162; Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: A Yank in the RFC/RAF,” p. 183.