(Chicago, June 3, 1894 – Pasadena, California, December 21, 1966).1

Matthiessen’s parents were first cousins; his sibling grandfathers were born in Altona in Schleswig Holstein (then part of Denmark). They emigrated to the Midwest, where they made large fortunes in the manufacture of zinc and the refinement of sugar.2 Matthiessen’s father, after studying at Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School, went into the family sugar business in Chicago.3 At least two members of the family became prominent outside the business world: Conrad Henry Matthiessen Jr.’s cousin, Francis Otto Matthiessen, the Harvard literary historian, and his nephew, Peter Matthiessen, the naturalist and writer.

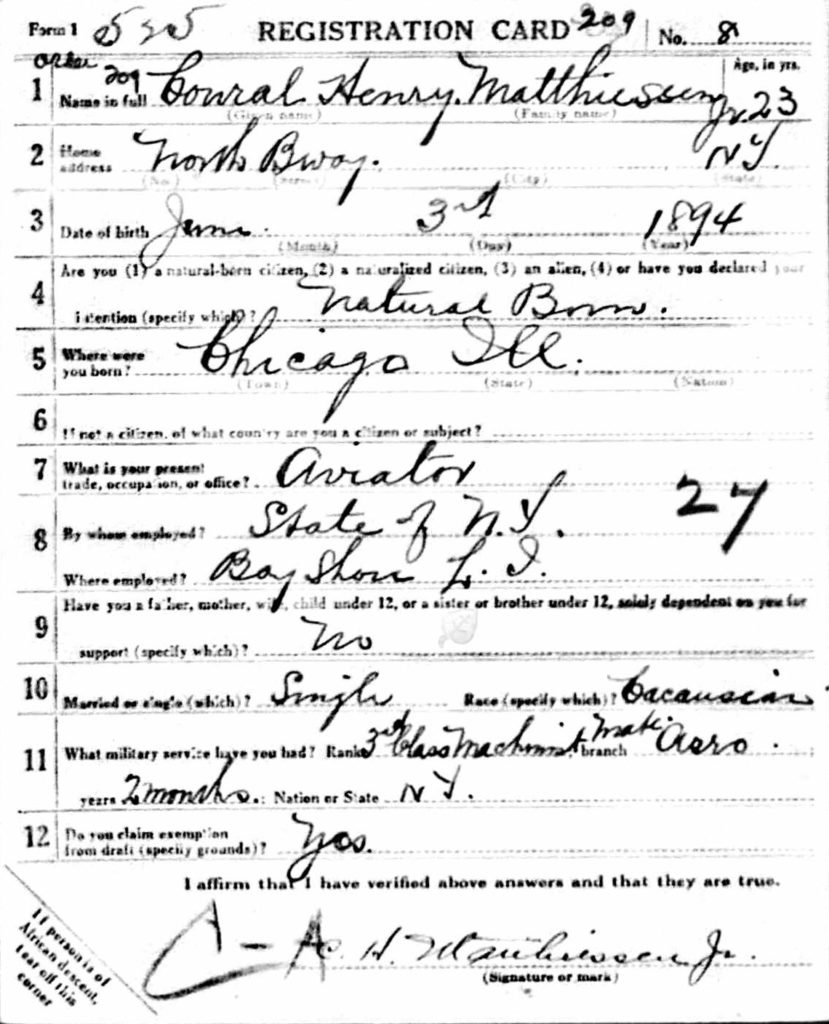

Conrad Henry Matthiessen, Jr., was the second of three surviving children, all sons. After attending Hotchkiss, he, like his father, studied at Sheffield, graduating in 1916.4 His family kept up ties to Europe, and Matthiessen was one of the relatively few second Oxford detachment members who had travelled to England, France, and Germany prior to 1917.5 When he registered for the draft, he listed his occupation as “aviator” at Bay Shore on Long Island, and noted that he had been employed as a “3rd class machinist mate” in the “Aero” branch of the military for two months. He attended ground school at M.I.T.’s School of Military Aeronautics, graduating August 25, 1917.6

Along with about one third of his ground school classmates, Matthiessen chose or was chosen for flight training in Italy and was thus one of the 150 members of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departed Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy but to remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. Various explanations have been offered for the snafu, to use an acronym from the next war.7 Whatever the reason, the detachment members fairly quickly made their peace with the change and in retrospect recognized the benefit of R.F.C. training.

At Oxford, initially, the cadets, as they were now called, were housed at Christ Church and Queen’s Colleges. After exuberant celebrations by members of both Oxford detachments, all the men were moved to Exeter College, thus, as it were, sequestering the Americans; the War Birds entry for October 22, 1917, provides a colorful account of the celebrations and their aftermath. William Ludwig Deetjen, who had been in charge of the men at Queen’s, wrote in his diary on October 23, 1917: “And then at noon we got orders to pack up and move to Exeter. . . . Now Exeter has no hot water, rotten meals, baths only from 2:30 to 4:00 P.M. and it is really uncomfortable. Queen’s College was heaven compared to this cold dump. One salvation is I room with Matthiessen, [Joseph Ralph] Sandford and [Phillips Merrill] Payson, all Tech men,” i.e., all men who had attended ground school at M.I.T.

The men spent two more weeks at Oxford and then, in early November, all but twenty of them (who were posted to a flying school at Stamford) were sent north to Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend gunnery school at Harrowby Camp. Matthiessen’s fellow Oxford detachment member Parr Hooper wrote of this move “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”8

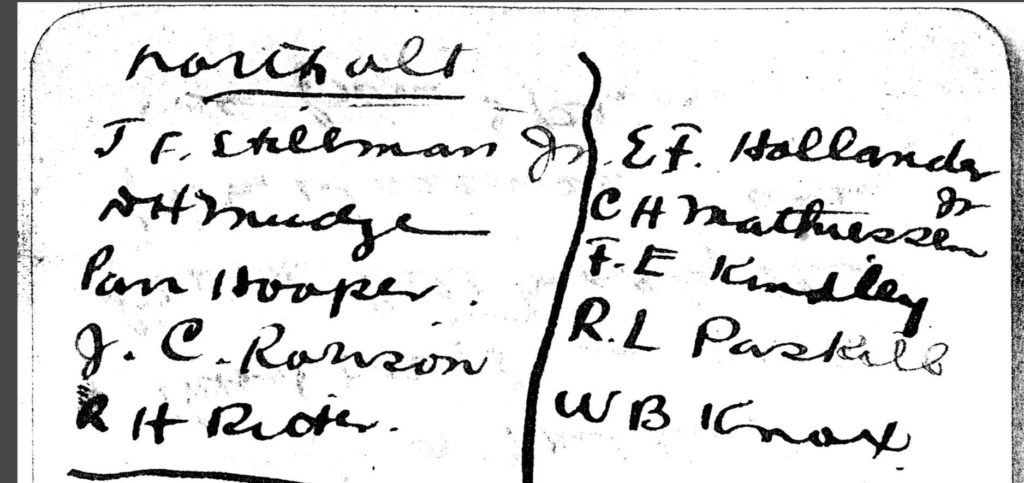

Fortunately for Hooper and Matthiessen, places opened up for fifty men at R.F.C. training squadrons in mid-November. They were among ten who were sent to Nos. 2 and 4 Training Squadrons at Northolt aerodrome, located at Ruislip in northwest Greater London (the others were Edward Frank Hollander, Field Eugene Kindley, Walter Burnside Knox, Dudley Hersey Mudge, Reuben Lee Paskill, Roland Hammond Ritter, John Chadbourn Rorison, and Joseph Frederick Stillman, Jr.) Matthiessen returned briefly to Grantham to take part in the Thanksgiving celebrations there.8a

At Northolt, when weather permitted, the cadets began flying instruction on Maurice Farman S.11 Shorthorns, flying “dual” with an instructor. On December 3, 1917, Matthiessen flew solo for the first time.9 Fairly quickly the men were able to “take their tickets,” i.e., complete the basic requirements (figure eights, landings, specified altitude) needed to qualify for a certificate in the Royal Aero Club.10

From Northolt Matthiessen was posted to London Colney and No. 74 Squadron, which was, until March 1918, a training squadron. James Ira Thomas Jones (“Taffy” Jones) was training there and recalled the influx of Americans: “Our school was lucky enough to get such grand types as Ken [sic] Curtis . . . Fred Stillman, Alexander Roberts, Clarence Fry, H. G. Shoemaker, C. Matthiessen, W. V. [sic] Wait and A. F. Morrison.”11 The aerodrome and accommodations were in general primitive, but some of the American cadets were lodged at the Red Lion in nearby Radlett where, as Marvin Kent Curtis wrote his sister, they were “more comfortably settled than at any other place I have been in the R.F.C. . . . I am rooming with five other Americans who came over with me, Fry of Columbia, Tenn., Fred Stillman, Matthiessen and [Glenn Dickenson] Wicks—all Yale men, and Austin Morrison of Iron River, Mich.”12

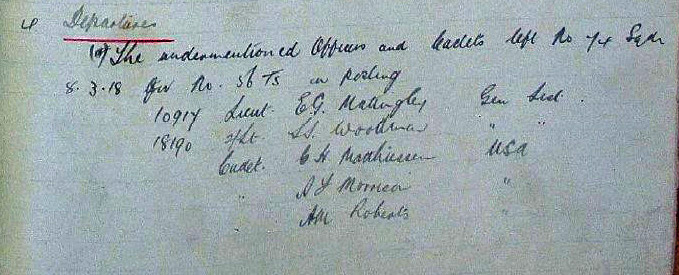

At London Colney Matthiessen would have trained on Avros, again initially dual and then solo. By mid-February he was ready to do the requisite cross country flight which typically consisted of flying south via Northolt to Hounslow and back.13 Jesse Campbell noted in his diary on February 17, 1918, that “Morrison, Matheson [sic], and Roberts did their cross country this afternoon and came back in fog.” Presumably not long after this Matthiessen moved on to training on Sopwith Pups and completed the other requirements to qualify for his commission and wings. On March 6, 1918, Pershing forwarded the recommendation for his commission to Washington; approval came back on March 17, 1918, and Matthiessen was placed on active duty on March 28, 1918.14

By this time, Matthiessen was at No. 56 Training Squadron, across the field at London Colney from No. 74. Early in March No. 74 had ceased to be a training squadron and was preparing to go to France, and the Americans in training were reassigned.

It appears that Matthiessen remained at London Colney until at least the end of April; Curtis, still at No. 56 T.S., wrote in a letter on April 28, 1918, of going into London with his roommate Matthiessen. In the same letter Curtis describes beginning to train on what are evidently Spads—although, wary of censorship, he does not actually name the type of plane—and it is likely that Matthiessen was making the same transition.

From London Colney, Matthiessen would presumably have gone to Turnberry on the west coast of Scotland to train in aerial gunnery. His last training posting was at the No. 1 School of Fighting a little way up the coast at Ayr, where he would have trained on S.E.5s and/or S.E.5a’s. His R.A.F. service record notes that on July 7, 1918, he proceeded from “1 Sch Fight” to “B.E.F.,” i.e., to the British Expeditionary Force in France, and that he was an “S.E.5 Pilot.”15 His casualty form, a record of active service postings, puts him at “No. 2 ASD” on this date, i.e., at the pilots pool at Rang du Fliers, near Boulogne, part of the No. 2 Aeroplane Supply Depot. There he would have waited to be assigned to a squadron; Austin Finley Morrison, according to the latter’s casualty form, joined him the next day.16 Like many others, they had to kick up their heels at No. 2 A.S.D. for a while, but eventually, on July 21, 1918, they were assigned to No. 74 Squadron R.A.F.—which meant they were back with many of the men they had trained with at London Colney. (Their fellow second Oxford detachment member, Alexander Miguel Roberts, had also been with No. 74, but had two days previously been shot down and made a prisoner of war.)

No. 74 Squadron flew S.E.5a’s and was stationed from April through September 1918 at Clairmarais near St. Omer, initially at Clairmarais Nord (where a casual photo of the squadron, including Matthiessen, was taken) and then, from early August at the newer aerodrome, Clairmarais Sud, only about a mile away.17 The squadron, commanded by Keith Logan Caldwell (“Grid” Caldwell), was part of the 11th (Army) Wing, II Brigade, attached to General Sir Herbert Plumer’s Second Army; the Second Army front ran approximately from Houthulst Forest south past Ypres to Nieppe Forest.18

From the Clairmarais aerodromes the pilots of No. 74 Squadron flew line and offensive patrols as well as, occasionally, escort, ground strafing, and wireless interception missions, all the while seeking to put enemy reconnaissance planes out of commission and to eliminate enemy scouts flying over and east of the Second Army front north and south of Ypres—all this is apparent from the account of No. 74 Squadron provided by Ira Jones in his Tiger Squadron. As with a number of other squadrons, the squadron record book and other relevant original documents appear not to have survived, and I can thus not provide details of Matthiessen’s activities. I find neither casualty nor combat reports for him, suggesting that he was not involved in incidents that resulted in injury to him or damage to his plane, and also that he made no combat victory claims. That he was assigned to C flight is supported by his appearance in an undated photo of that flight, along with Clive Beverly Glynn (apparently the flight leader), Harold Goodman Shoemaker, Frederick Stanley Gordon, John Adamson, Jr., and William Couper Goudie. The photo is undated, but must have been taken before Shoemaker left on August 27, 1918, for the U.S. 17th Aero.19

On September 19, 1918, Matthiessen left No. 74 Squadron for the American 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun.20 From there he, like a number of other Americans who had been serving with R.A.F. squadrons, was assigned to the U.S. 25th Aero Squadron—efforts to pin down the date when he joined the squadron and how long he remained have been unsuccessful.20a

Entries in Joseph Kirkbride Milnor’s diary for October 9 and 15, 1918, indicate that Matthiessen, along with Frederic Ernest Luff (also of No. 74 and the 25th Aero), was in London during that period, perhaps on leave, or perhaps ferrying S.E.5s destined for the 25th from England to France. And Matthiessen was in London on November 12, 1918, as attested by another entry in Milnor’s diary: “Matty came in during the afternoon and the three of us are going to celebrate tonight.” Milnor, Matthiessen, and Morrison, who was sharing a flat with Milnor, celebrated the end of the war together into the early hours of the morning.

It was not until shortly before the armistice that the 25th Aero Squadron had any of the S.E.5s they were to fly; by the skin of their teeth they became operational before the armistice, but did not see combat. Official photos were taken of the squadron at Toul, and Matthiessen appears to be the tallest of the pilots in one of them taken in front of a Spad XIII ; he is third from the left in the front row of a more formal group photo. He also appears in informal photos taken by Second Oxford detachment members John Chadbourn Rorison and Donald Swett Poler, both of whom were also assigned to the 25th Aero.21

Matthiessen was able to return to the U.S. early in 1919; he, along with fellow second Oxford detachment members Leonard Joseph Desson and Clair Rutherford Oberst boarded the U.S.S. Finland at St. Nazaire on January 31, 1919, and arrived back in New York on February 14, 1919.22 Matthiessen went into manufacturing and was the applicant on a number of patents, including one for an airplane.23 At some point he and his growing family relocated to southern California, where he died in 1966.

mrsmcq November 29, 2019; September 29, 2020, reflecting Milnor’s diary

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Matthiessen’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Conral Henry Matthiessen Jr. Jr [sic]. His date of death is taken from Ancestry.com, California, Death Index, 1940–1997, record for Conrad H Matthiessen; the place is inferred from “Matthiessen Services Friday.” The photo is a detail from a photo kept by Joseph Raymond Payden of the men in his M.I.T. ground school class.

2 Information on Matthiessen’s family is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 See A History of the City of Chicago, p. 467.

4 Scott, Class History 1916 Sheffield Scientific School, pp. 180–81.

5 See Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925, record for Conrad Henry Matthiessen Jr (1921).

6 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

7 See, for example, the explanations supplied by Hamilton Hadley on p. 4 (286) of “Foreign Aviation Detachments,” by Geoffrey Dwyer on p. 2 of “Report on Air Service Flying Training Department in England,” and by Claude E. Duncan as recorded in Sloan and Hocutt, “The Real Italian Detachment,” p. 44.

8 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

8a This according to Deetjen’s diary entry for November 30, 1917.

9 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 4, 1917.

10 This is based on the experiences of Hooper and Roland Hammond Ritter, who “took their tickets” on December 6 and December 7, 1917, respectively.

11 Ira Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 60.

12 Curtis, letter of January 19, 1918.

13 Ira Jones, Tiger Squadron. P. 61.

14 Cablegrams 691-S and 936-R; McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

15 The National Archives (UK), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Mathiessen [sic].

16 “Lieut. C H Matthiessen” and “Lieut. A F Morrison USAS.”

17 On the sites of the World War I Clairmarais aerodromes, see O’Connor, Airfields and Airmen of the Channel Coast, Chapter 3, and “Aérodromes britanniques situés dans le Pays de Saint-Omer.” From these sources it appears that the aerodromes were about three and a half miles east of the village of Clairmarais, on the eastern edge of the Forêt de Clairmarais. The informal squadron photo appears after p. 144 of Ira Jones’s Tiger Squadron (“Outside the Officers’ Mess, Clamarais [sic], St. Omer, September, 1918,” probably misdated), and after p. 304 of Revell’s British Single-Seater Fighter Squadrons on the Western Front in World War I (“74 Squadron outside the officer’s Mess at Clairmarais North, early [sic] July 1918”). See also “74 Sqdn people,”“WW1 R.A.F. Photo Album,” and “74 Squadron with the letter ‘C’ on the fuselage.”

18 This is the description of the Second Army front in the late spring and summer of 1918 provided by Blanford, “Sans Escort,” part 1, p. 147.

19 I am grateful to Bob Cossey of the 74(F) Tiger Squadron Association for a copy of the photo.

20 “Lieut. C H Matthiessen.”

20a “History of 25th Aero Squadron, (Pursuit),” p. 6, lists Matthiessen as one of the pilots assigned, implicitly, after the armistice, but a previous listing, p. 5, calls this dating into question for at least some of the names. Matthiessen does not appear on the roster dated December 12, 1918, on p.7 of the same history. See also Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” p. 23.

21 See Doyle, “War Bird Pictorial,” p. 50, for Rorison’s photo of Matthiessen. Poler’s photo of 25th Aero pilots Paul Verdier Burwell, Eugene Hoy Barksdale, Frederic Ernest Luff, and Matthiessen is reproduced on p. 28 of Sloan, “The 25th Aero Squadron,” as well as on p. 206 of Sloan’s Wings of Honor.

22 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Casual Officers Detachment, on Finland.

23 See Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Conrad Henry Matthiessen Jr. (1921), for his occupation. See Index of Patents Issued from the United States Patent Office, p. 456.