(Lodgepole, Nebraska, February 5, 1894 – near Stenay, France, November 4, 1918).1

Training in England ✯ 11th Aero Squadron ✯ November 4, 1918

Coates came of restless pioneer stock. His paternal grandfather, born in Vermont, moved to Ohio prior to the Civil War and became a lawyer and newspaperman.2 Coates’s father, Charles Nelson Coates, worked as a telegrapher and railroad agent, initially in Ohio, then in Lodgepole, Nebraska. In 1885 he married Amanda B. Jones, whose Welsh ancestors had settled initially in Pennsylvania before moving west. Seven children, three boys followed by four girls, were born in Lodgepole; Dana Edmund Coates was the third boy. His parents went on to homestead in Hillsdale, Wyoming, and to have another son and two more daughters before relocating to Denver, where Charles Nelson Coates taught telegraphy.3

I have not found any record of Dana Edmund Coates’s activities between 1910 and and 1916 and thus nothing to indicate whether he attended college. In 1916 he was living in Denver and working as a clerk at the A. S. Carter Company, a maker of Freemason products.4 That year he joined the Colorado National Guard and was presumably for a time stationed at Douglas, Arizona, on the Mexican border, when the Guard was deployed during the Mexican Punitive Expedition.5 When Coates registered for the draft on May 29, 1917, he was in the Student Officers Training Corps at Fort Riley, Kansas. He attended ground school at the University of Illinois, graduating September 1, 1918.6

I have not found any record of Dana Edmund Coates’s activities between 1910 and and 1916 and thus nothing to indicate whether he attended college. In 1916 he was living in Denver and working as a clerk at the A. S. Carter Company, a maker of Freemason products.4 That year he joined the Colorado National Guard and was presumably for a time stationed at Douglas, Arizona, on the Mexican border, when the Guard was deployed during the Mexican Punitive Expedition.5 When Coates registered for the draft on May 29, 1917, he was in the Student Officers Training Corps at Fort Riley, Kansas. He attended ground school at the University of Illinois, graduating September 1, 1918.6

Along with most of his ground school classmates Coates chose or was chosen for flight training in Italy and thus became one of the 150 cadets of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York September 18, 1917, making a stopover at Halifax to join a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, and arrived at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. The cadets sailed first class and enjoyed some leisure, including concerts featuring the violinist Albert Spalding, also on board. They had Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, and, once the convoy entered dangerous waters, they took turns at submarine watch.

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment members learned that they were not to continue on to Italy, but to remain in England for their training. They travelled by rail to Oxford, where they spent the month of October repeating ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. As much of their class work involved material already covered in the U.S., the cadets (as they were now called) did not have to study particularly hard, and they enjoyed exploring Oxford and the surrounding countryside.7 Coates was apparently among those invited one afternoon to tea by Sir William Osler and his wife, whose Oxford residence was opened to many American and Canadian servicemen.8

The men were eager to start learning to fly, but, because there were not enough places at training squadrons, most of them, including Coates, were sent at the beginning of November 1917 to the machine gunnery school at Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire. Fifty cadets were able to leave Grantham for flying schools on November 19, 1917, but Coates was among those who remained at Grantham through the end of November to complete courses on the Vickers and the Lewis machine guns.

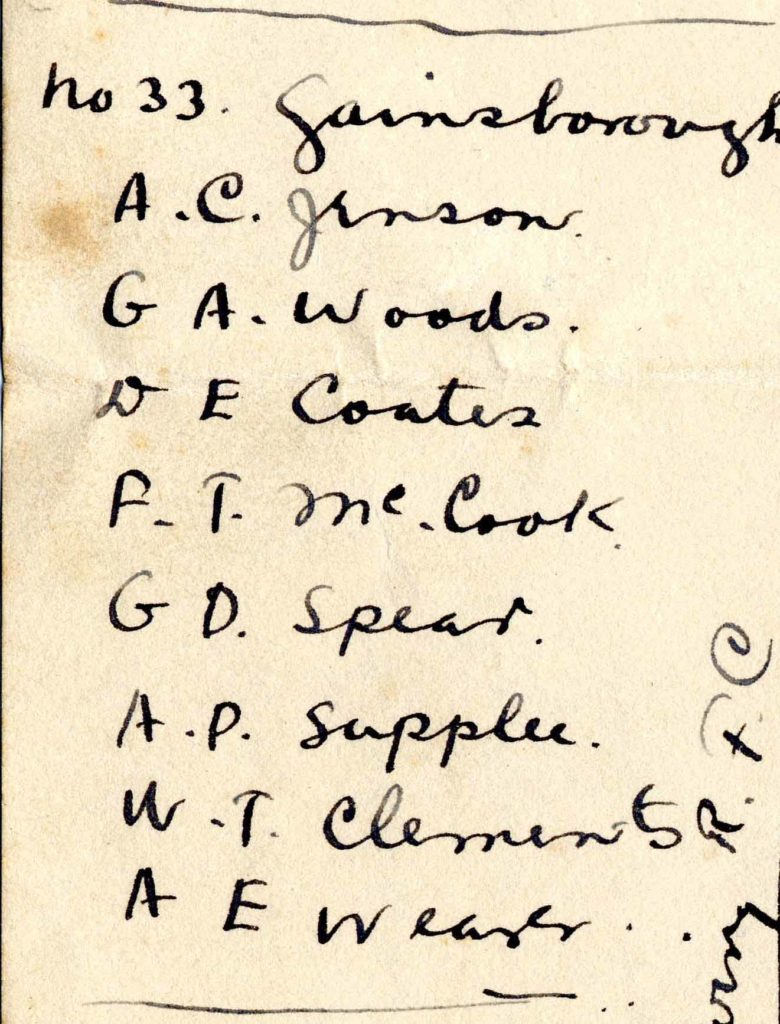

Finally, on December 3, 1917, the remaining cadets were posted to flying squadrons. Coates was one of eight assigned to No. 33 Home Defense Squadron, headquartered at Gainsborough, about thirty-five miles north of Grantham.9 However, as, William Thomas Clements, also assigned to Gainsborough, wrote in his diary, “they didn’t know what to do with us after we got up there . . . We were sent out here to Scampton,” where a flight from No. 33 was located; Scampton was about ten miles southeast of Gainsborough and not far from Lincoln.10 Clements enthusiastically describes being taken up in an airplane for the first time the day after he and the other seven men arrived at Scampton and notes that “All of the boys had a ride, and some had two. The pushers are not dual control so all we are getting out of it is riding.”11 Clements, Coates, and the others were evidently being taken up as passengers in the F.E.2b’s and/or the F.E.2d’s used by No. 33.12 These pushers (i.e., planes with the propeller behind the engine) were used by home defense squadrons for night fighting and were not designed as training planes. For the best part of two months the men made occasional flights as passengers but were otherwise at loose ends.13 Murton Llewellyn Campbell, posted to No. 81 Squadron, also at Scampton, wrote in his diary on December 29, 1917: “Ran across several of the fellows in the Home Defense Sq. . . . They have had nothing but joy riding with no instruction. Rather unfortunate, except that they have nothing to do but sit around and read.” It was surely frustrating for Coates to watch men like Murton Campbell at the same airfield flying Avros and Pups simply because they had been assigned to a different squadron. Finally, on January 26, 1918, the eight men at Scampton were reposted. Clements’s diary entries for January 26 and 27, 1918, indicate that he, Arthur Paul Supplee, and two others (unnamed) went to Waddington; “the other four” (also unnamed) “are going down near London some place.”

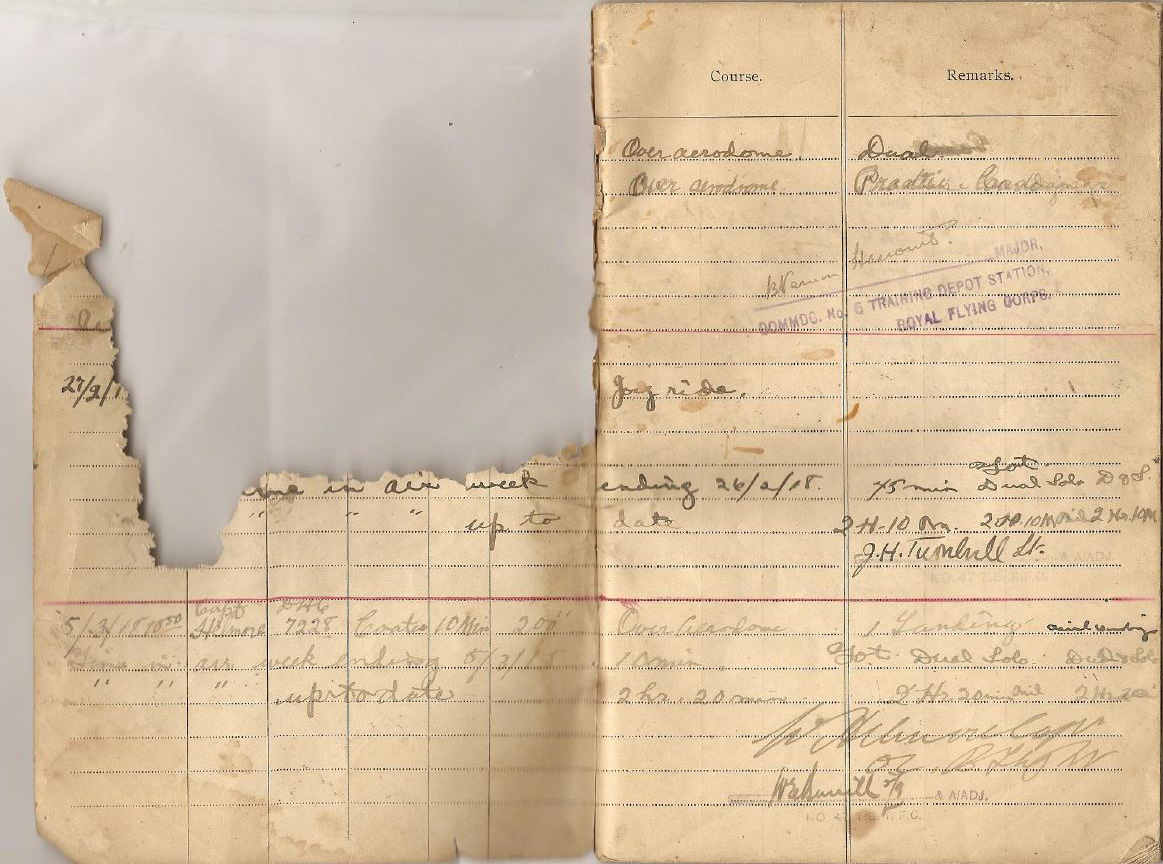

Coates was evidently in the latter group. “Near London” was a relative description, for Coates’s pilot’s flying log book shows that in February 1918 he was at No. 6 Training Depot Station at Boscombe Down in Wiltshire, about ten miles north of Salisbury.14 The log book has sustained damage, but it is clear that there is an official signature and stamp from No. 6 T.D.S. certifying entries before the end of February 1918. The planes available at 6 T.D.S. were (in addition to Avros) B.E.2c’s, B.E.2e’s, and DH.6s—all two seaters designed or now used for training—and DH.4s, DH.9s, and FK.8s, two-seater operational aircraft used for reconnaissance and bombing.15 In Coates’s relatively brief time at No. 6 T.D.S., his flying was probably confined to the training planes.

Coates’s log book shows that at the end of February 1918 he went back up north to No. 47 Training Squadron at Waddington, just south of Lincoln, where he initially put in a good deal of time on DH.6s. He first flew solo in a DH.6 on March 9, 1918. He went up as a passenger in an Armstrong Whitworth FK.8 a number of times before flying AW FK.8 B9638 solo on March 26, 1918.16 That same day he did a solo cross-country flight, one of the major prerequisites for graduating from the first stage of R.F.C. training. By the end of the month he had accumulated thirty hours of flying, two thirds of them solo. He flew a “service machine”—in Coates’s case an R.E.8—solo on April 23, 24, and 26, and the next day passed his height test, going up to 8,000 feet. He had now fulfilled the requirements for graduation from this stage of R.A.F. training.16a

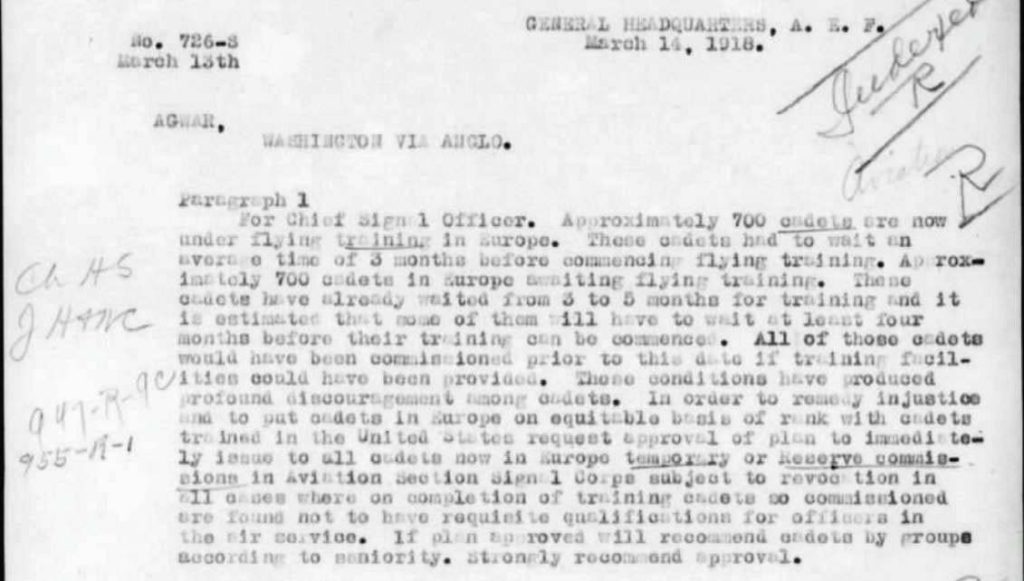

Meanwhile there was also the question of his commission. Pershing had been made aware that many cadets in Europe were unhappy that they had not yet been made first lieutenants. In a cablegram to Washington dated March 13, 1918, Pershing described the situation of the approximately 1400 aviation cadets in Europe, some of whom had waited three months to start flying training, and some of whom, after five months, were still waiting and might have to wait another four. “All of those cadets would have been commissioned prior to this date if training facilities could have been provided. These conditions have produced profound discouragement among cadets.” To remedy this injustice, and to put the European cadets on an equal footing with their counterparts in the U.S., Pershing asked permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .” Washington approved the plan in a cablegram dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.” This explains why Pershing stipulated a status of “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying” in his April 8, 1918, cablegram recommending that Coates, along with thirty-eight other second Oxford detachment members, as well as many other cadets, be commissioned.

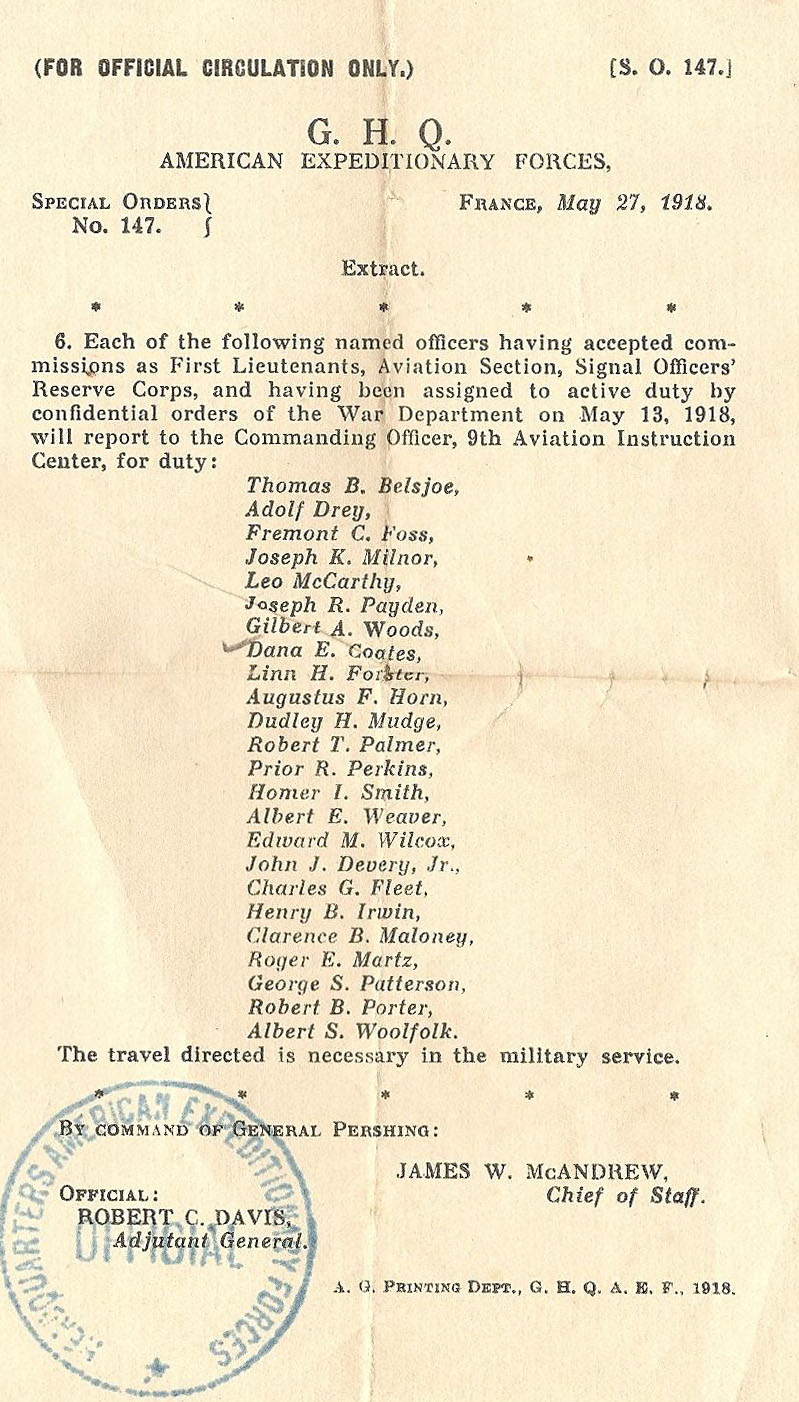

Washington took its time responding to Pershing’s April 8, 1918, cablegram. On April 30, 1918, Pershing wrote: “Request action taken on . . .” and lists cablegrams dated March 29 through April 8, 1918. The confirming cablegram from Washington, finally, is dated May 13, 1918.17 For Coates and most of the other second Oxford detachment members listed in the April 8, 1918, cablegram, the “non-flying” status was irrelevant, as they could attest to “satisfactory completion of flying training” by the time word of the May 13, 1918, cablegram from Washington trickled down.

Coates kept a copy of an extract from Special Orders 147 dated May 27, 1918, that recorded that he and a number of others had been commissioned and placed on active duty by the May 13, 1918, cablegram.18

At the end of May 1918 Coates was assigned to No. 44 T.S., still at Waddington, and began flying in a DH.9, flying one solo for the first time on June 2, 1918, and passing a new height test, this time an altitude of 17,000 feet, three days later. Over the course of June and well into July, flying DH.9s, Coates practiced formation flying and aerial fighting, and, day after day, fired at ground targets at nearby Saxilby. His last recorded flight at Waddington was on July 10, 1918.19

On July 12, 1918, Coates, along with fellow second Oxford detachment members Fremont Cutler Foss, Joseph Raymond Payden, George Dana Spear, Perley Melbourne Stoughton, Supplee, and Gilbert Allan Woods, was ordered to No. 2 Fighting School at Marske-by-the-Sea in the northeast of Yorkshire.20 There was presumably some initial ground work, and then, on July 18, 1918, Coates was back in the air in an Avro, as a passenger. He quickly passed on to flying an Airco DH.9A with a liberty engine, solo and with a passenger, as well as DH.9s, and he practiced firing, aerial fighting, and formation flying. By the end of the course at Marske he had flown 12 hours there and had accumulated nearly 156 hours total flying time.

From Marske Coates went at the end of July 1918 to Norwich in Norfolk, to No. 117 Squadron. There, from July 30 through September 7, 1918, he flew DH.9s, DH9A’s, R.E.8s, and, for the first time, DH.4s. Much of his time at No. 117 was spent testing planes and acting as a ferry pilot. He delivered planes to Sedgeford, Waddington, Thetford, and Salisbury, and on one occasion, to Marquise in France.

On September 20, 1918, Coates, along with fellow second Oxford detachment members Ralf Andrews Crookston and Spear, arrived at Amanty and reported there to the U.S. 11th Aero Squadron, one of the squadrons flying American “Liberty” DH-4s.21 The 11th had arrived in France in mid-August. Its first flying officers arrived on September 1, 1918; more of them (including Vincent Paul Oatis, Robert Brewster Porter, Fred Trufant Shoemaker, and Walter Andrew Stahl from the second Oxford detachment) arrived shortly before the opening of the St. Mihiel Offensive.22 With inadequately prepared planes and most of its pilots inexperienced in combat, the 11th joined the 96th and 20th Aero Squadrons to make up the 1st Day Bombardment Group on September 10, 1918, two days before the opening day of the St. Mihiel Offensive, which it was to support. By the end of the day on September 18, 1918, fourteen pilots and observers from the 11th had been killed or taken prisoner, including the commanding officer. This was the decimated and demoralized squadron that Coates joined two days later.

The new C.O. assigned to the squadron was Charles Louis Heater, whom Coates presumably already knew from the second Oxford detachment. Heater had considerable experience flying DH.4s with No. 55 Squadron of the Independent Air Force, and between his skilled leadership and recognition by higher ups that changes needed to be made, the 11th was able to come back from the brink. In a very short period, Heater taught his pilots close formation flying, and the 1st Day Bombardment Group would start using larger and thus better protected formations during the Meuse–Argonne Offensive, whose way had been prepared by St. Mihiel.23

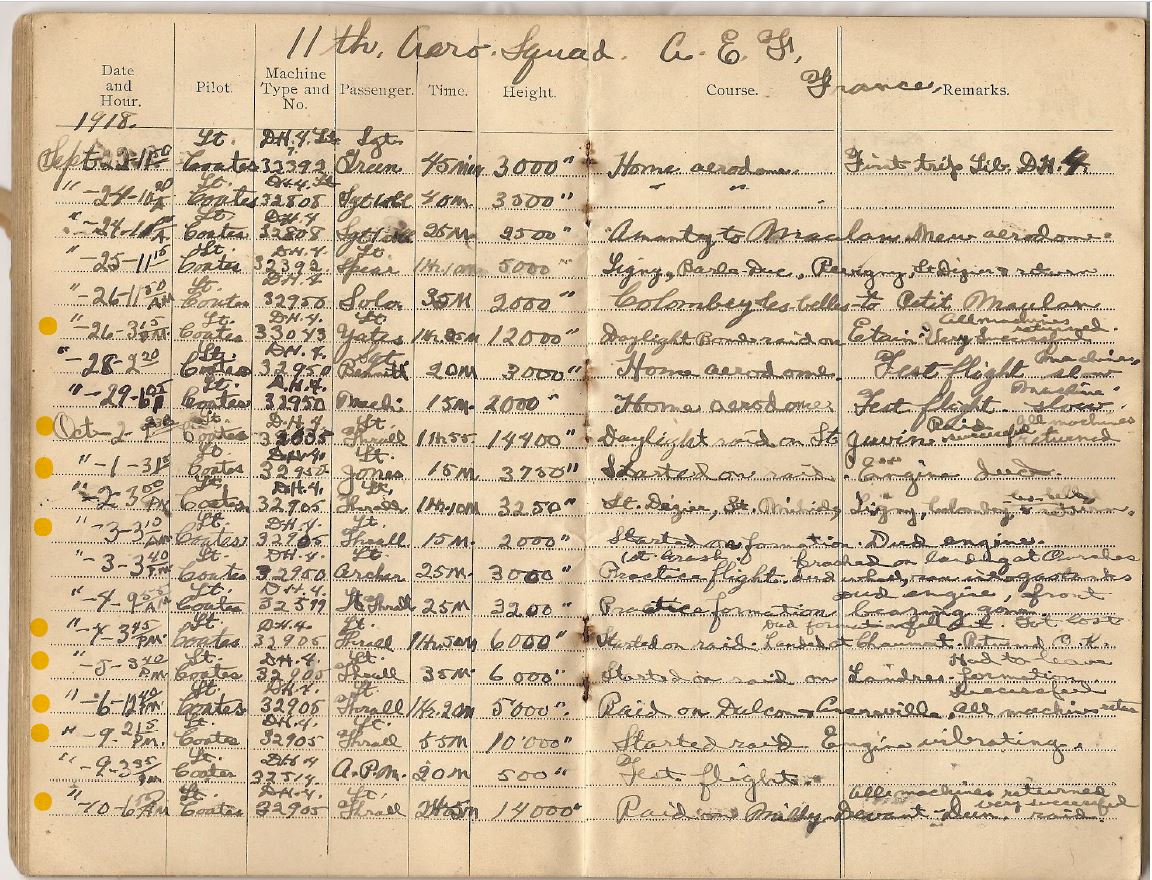

Two days after arriving at Amanty, Coates, with one of the enlisted men, Hal Louis Green, as his passenger, made his “First trip Lib DH.4,” a forty-five minute flight near the aerodrome. He made a similar flight the morning of September 24, 1918, before making the twenty-five minute flight from Amanty to Maulan, twenty miles to the northwest, where the 1st Day Bombardment Group was being relocated prior to the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The next day he took Spear up with him on a longer cross-country flight, getting to know the area around Maulan.

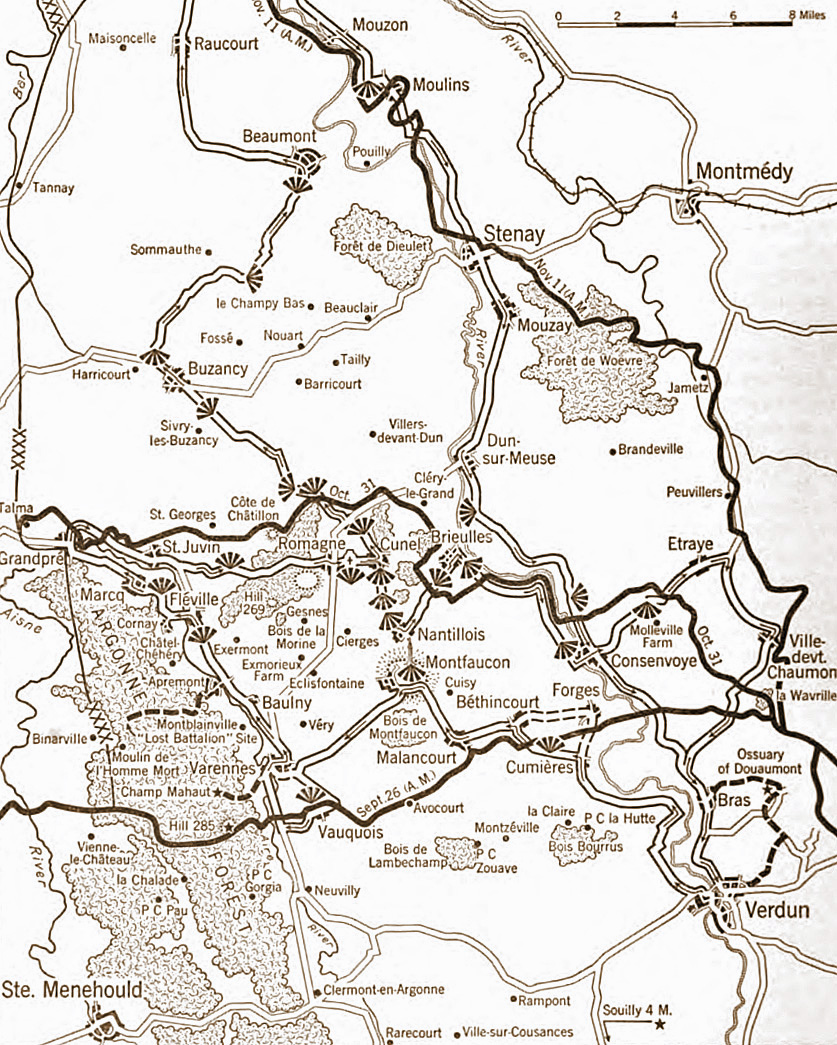

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive opened in the very early hours of September 26, 1918. That morning the First Day Bombardment Group bombed Dun-sur-Meuse, and the 20th Aero suffered losses that recalled those of the 11th from earlier in the month. Coates was not assigned to this mission, but rather was tasked with going to the American 1st Air Depot at nearby Colombey-les-Belles to pick up a DH-4 and ferry it back to Maulan. He flew his first combat mission, with James Stephen Yates as his observer, that afternoon, when eight planes from the 11th led by Cyrus John Gatton, soon followed by six planes from the 20th, set off for Etain, some forty miles north-northeast of Maulan and a few miles over the lines east of Verdun. They dropped their bombs and “all machines returned. Very successful,” as Coates noted in his log book.24 His words are echoed in the history written shortly after the war: “This was the first successful raid we had made in comparative safety and everyone could notice the improved morale resulting from it.”25

On September 27, 1918, a number of pilots from the 11th and 20th were drafted in to fly Breguets with the 96th, which was short of pilots, a practice which would continue for some time. A similar mission the next day was cancelled due to a rainstorm.26 Coates, who had no experience flying Breguets, remained at Maulan testing the plane (DH-4 32950) that he had just brought over from Columbey; he found it slow.

On September 29, 1918, two large formations, one of Breguets and one of DH-4s with pilots and observers from the 11th and the 20th, set out late in the afternoon to bomb Grandpré and Marcq, nearly fifty miles north of Maulan. There is no entry for this mission in Coates’s log book, but he is listed with observer Morton Forrest Bird in the operations report of the 1sth Day Bombardment Group as among the twenty teams who set out with the DH-4 formation and as among the many who had to return early because their planes “could not keep up with formation.”27 It is not clear whether the operations report is in error or whether Coates failed to record the mission—irregularities in dates around the turn of the month in the log book suggest he may have made entries some time after the fact and have overlooked a flight.

The next mission of the 1st Day Bombardment Group, on October 1, 1918, was similar: two large formations, most of the Breguets of the first formation reaching their objective, most of the DH-4s of the second formation having to return before reaching the lines, including Coates with Horace H. Jones, Jr., as his observer. Coates’s plane was 39250, the one he had brought from Maulan and found slow; apropos this mission he wrote in his log book: “Started on raid. Engine dud.”

The next day’s raid was again similar in that there was a large formation of Breguets followed by one of DH-4s, but most of the DH-4s, including apparently Coates’s, flying at over 14,000 feet, succeeded in reaching and bombing the target, St. Juvin, just south of Grandpré. Coates’s observer was, for the first time, Loren Renfrew Thrall, the man who would accompany him on most of his subsequent flights. It also appears—though the writing in his log book is hard to decipher—that on this mission Coates for the first time flew DH-4 32905, which he would pilot on most of his subsequent flights. In the afternoon of October 2, 1918, Coates and Thrall in 32905 made a cross country flight similar to the one Coates had taken on September 25, 1918, presumably to introduce Thrall to the area and to gain greater familiarity with the plane.

Over the next three days (October 3–5, 1918), both DH-4s, 32905 and 32950, let Coates down. In the middle of the afternoon on October 3, 1918, Coates and Thrall set out in the former, but cut their flight short after fifteen minutes with a “dud engine.” Almost immediately, Coates went up again for a practice flight, this time in DH-4 32950 with Hasell Davies Archer as his observer. He experienced his first crash when he landed at Ourches, due, apparently, to a “dud wheel [?]”; neither man was hurt. On the 4th and 5th, Coates and Thrall started out on afternoon missions in D32905, and both times had to turn back. On the afternoon of the 4th it was apparently the formation that was “dud,” and none of the DH-4s made it across the lines. Coates noted in his log book: “Fell out. Got lost. Landed at Chaumont. Returned OK.” If this was Chaumont, Haute-Marne, then he and Thrall were well and truly lost and some forty miles to the south of Maulan. The next afternoon Coates and Thrall set out as part of a formation of twenty DH-4s to bomb Landres, but “had to leave formation,” as did four other planes.28

Over the course of October, Coates, with Thrall as his observer and, as far as can be determined from the records, flying DH-4 32905, participated in ten more raids, i.e., nearly every raid flown by the 11th Aero. On October 10 and 30, 1918, they took part in two raids each day. Their success was mixed; on October 9, 1918, Coates and three others out of a flight of ten did not reach the objective; Coates noted in his log book that he was flying DH-4 32905: “Started raid. Engine vibrating.” The next day, however, on two raids, Coates, Thrall, and 32905 were successful in reaching targets just north of Dun-sur-Meuse.

Coates’s log book ends with the raids of October 10, 1918—whether because the book was misplaced or because Coates failed to keep it up cannot be determined. Thus there are no explanations offered when, on four occasions, Coates was among the pilots recorded as unable to reach the mission’s objective,29 but it seems likely that an unreliable plane was sometimes the problem. And on October 23, 1918, although Coates and Thrall apparently reached Buzancy and Bayonville, they “could not drop bombs,” suggesting mechanical issues. They and 32905 did not take part in that day’s second mission, and “unfavorable” weather meant that the 1st Day Bombardment Group undertook no missions on October 24–26, 1918.30

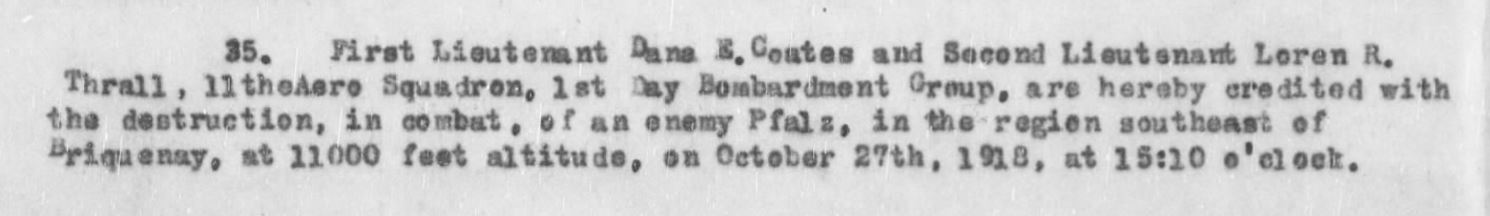

Weather having improved somewhat, though visibility was still “very poor,” a large mission, including twelve DH-4s of the 11th, set out to bomb Briquenay in the early afternoon of October 27, 1918. The record in the not always reliable operations reports states that Coates, Thrall, and plane no. 18 (32905) “did not reach objective.”31 This is either an error, or else their plane got near enough as makes no difference, for, in the course of an attack on the formation in the vicinity of Briquenay, Coates and Thrall, flying at 11,000 feet, shot down an enemy plane. The squadron’s raid report describes the plane as “seen to have gone down out of control”,32 while in General Orders No. 23 Coates and Thrall are officially “credited, in combat, with the destruction of an enemy Pfalz.”33

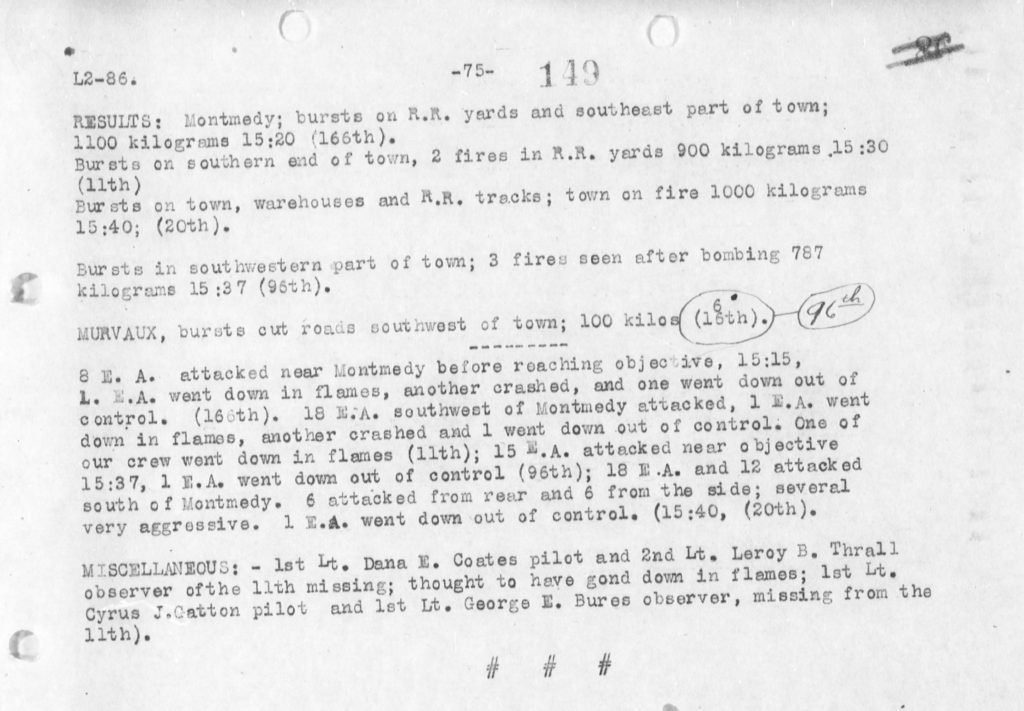

The 11th Aero, after the disaster of St. Mihiel, fared much better during the Meuse–Argonne Offensive, thanks in part to the use of larger, tighter formations. The squadron lost no men up until their penultimate mission of the war on November 4, 1918 (and no planes from the 11th actually crossed the lines on the final mission the next day). The late afternoon raid on Montmédy on November 4, 1918, in which approximately forty-eight planes from the four squadrons of the 1st Day Bombardment Group (which now included the 166th) participated, encountered aggressive attacks by enemy aircraft over the course of twenty-five minutes as they approached the target and as, having dropped their bombs, they turned towards home.34 Two planes from the 11th did not return to Maulan: “1st Lt. Dana E. Coates pilot and 2nd Lt. Leroy B. Thrall [sic] observer of the 11th missing; thought to have gone down in flames; 1st Lt. Cyrus J. Gatton pilot and 1st Lt. George E. Bures observer, missing from the 11th.”35

The History of the 11th Aero Squadron, U.S.A. provides this account:

The main formation found trouble waiting for them just after bombing, when eighteen or twenty Fokkers attacked them in a mass. A strong head wind was retarding our formation’s return over enemy territory and the Huns made the most of their opportunity. . . . Coates and Thrall, superior flyers and fighters, were flying one of the rear positions, and these were called on to bear the brunt of the fight. In spite of almost perfect defense the outnumbering Huns came in closer and finally Coates’ plane was seen to burst into flame and start downward. But neither he nor Thrall were through yet. Coates side-slipped his plane first one way then the other, in an effort to hold the fire only in the tanks; Thrall kept his guns going and got one of the Huns who were following them down. This fight against odds that were unbeatable kept on as far as the machine could be seen, but it was a losing one, for the bodies of the men were found near the charred remains of the plane and buried there near Stenay by the peasants.36

An unidentified squadron member wrote: “On the raid of November 4th Coates and Thrall were just ahead of me during the awful fight. Thrall was down in his cockpit, struggling to stand and shoot, but fell back time after time, undoubtedly badly wounded in the first of the fight. Both he and Coates were fighting even as their machine went down, leaving a trail of dense black smoke behind.”37

Gareth Morgan has written that the German pilot who shot down Coates and Thrall was Friedrich Noltenius of Jagdstaffel 11, a Fokker DVII squadron stationed at this time at Marville, just a few miles southeast of Montmédy.38 Noltenius’s diary entry for November 4, 1918, recounts his having set off at 4 p.m. on his second mission of the day and attacking three separate planes during an encounter with a bomber formation in the vicinity of Carignan (about twelve miles northwest of Montmédy). Noltenius’s account of the second attack, referring as it does to a plane in the rear position, may be a description of Coates’s plane being shot down: “I turned off in the direction of the main formation, where we met head-on over Carignan. Weaving heavily, I passed by the ten D.H.s and with a smart turn positioned myself behind the rearmost one. In a longer battle I first shot him smoking, and then shot his engine to pieces. This slowed him down; then I got nearer and shot him down in flames. (21st confirmed victory).”39

The entries for this date in Franks, Bailey, and Duiven, The Jasta War Chronology, include a combat victory for G[eorg] von Hantelmann of Jasta 15 near Stenay with the note that his victim was Coates’s DH-4 32905.40 The entry for Coates in Henshaw’s The Sky Their Battlefield reads in part “[bombing mission to] Cheveney le Château combat with 18 Fokker DVIIs . . . heavily shot up fuel tank on fire, down in flames crashed near Stenay,” but Henshaw does not speculate on the identity of the pilot responsible for downing Coates’s plane.41 The 11th Aero was credited with downing four German planes during the combat near Stenay on November 4, 1918.42

Coates and Thrall were initially listed as missing in action, but by early 1919 they were moved from the missing to the killed in action list.43 Hard as this must have been for Coates’s family, it would have been even harder for Thrall’s; his only sibling, Lloyd Elton Thrall, a member of Company L, 41st Infantry, stationed at Camp Funston in Kansas, had died October 16, 1918.44

Coates and Thrall, as described in the post-war squadron History cited above, were buried near their crash site in the vicinity of Stenay. According to a newspaper story distributed initially on March 3, 1923, one of the graves was marked with Coates’s name, the other as “unknown.” When the bodies were disinterred in order that they could be reburied in a military cemetery, a laundry mark, “L. R. T.”, was discovered on the clothing of the unidentified man, along with a label indicating the uniform had been made by a firm in Rochester, N.Y. Inquiries of retail firms that had carried the uniform led to a store in Austin, Texas, where Thrall had bought one on February 8, 1918, a week before he graduated from the University of Texas ground school. Military records confirmed that Thrall had been flying with Coates, and identification was complete.45

Thrall was reinterred in the cemetery in his home town of Bone Gap, Illinois, where his brother was also buried.46 Coates’s final resting place was in France, in the Meuse–Argonne American Cemetery in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, about ten miles south of where he was shot down.47 His mother was able to visit the grave in 1930.48

mrsmcq June 3, 2017; revised, based on log book, April 5, 2021

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 The spelling of Coates’s middle name (sometimes given as Edmond) and his date and place of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Dana Edmund Coates. The photo is one that has been handed down in Coates’s family to a great-nephew and is attached to Thompsor58 [pseud.], “Thompson Family Tree,” record for Dana Edmund Coates.

2 On John Briggs Coates, see Durant, A History of Union County, part 5, p. 87.

3 On Coates’s descent generally, see documents available at Ancestry.com. On Charles N. Coates, see Ancestry.com and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1880 United States Federal Census, record for Charles M Coats [sic]; Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Chas N Coates; Dobson, “Lincoln Highway Photos”; and entry for Charles N Coates in Ballenger and Richards Denver Directory 1916.

4 Ballenger and Richards Denver Directory 1916; “Local Mention.”

5 See Coates’s draft registration, cited above, and Thompson, “The Unusual Service of Lt. Dana Coates.”

6 See “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

7 Morgan, “From Lodgepole to Stenay,” suggests Coates initially did basic flying training at No. 44 T.S. Waddington before going to Oxford, a misunderstanding probably due to incomplete sources.

8 Morgan, “From Lodgepole to Stenay.”

9 Foss, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” (in Foss, Papers).

10 Clements, “World War Diary of W. T. Clements 1917-1918,” entry for December 3, 1917.

11 Clements, diary entry for December 4, 1917.

12 On the planes available to the squadron, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 401.

13 Clements, diary, passim.

14 Here and in what follows, information on individual flights made by Coates are based on his log book unless otherwise noted.

15 On the aircraft at Boscombe Down, see Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 294.

16 I have supplied the letter prefix in the plane’s serial number; Coates consistently transcribed serial numbers without their letters.

16a See here for the R.F.C. graduation requirements; I find no similar document indicating the requirements for a commission, but there was an understanding that a pilot had to have flown twenty hours solo; see, for example Hooper, Somewhere in France, letters of December 28, 1917, and January 31 and February 14, 1918.

17 See cablegrams 726-S (March 13, 1918), 955-R (March 21, 1918), 874-S (April 8, 1918), 1029-S (April 30, 1918), and 1303-R (May 13, 1918).

18 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 147.”

19 History of 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A. errs in stating, p. 13, that “Charles Dana Coates” [sic] left for France in early July 1918.

20 Biddle, “Special Orders No. 116.”

21 See “11th Squadron,” pp. 4–5. Conventionally in secondary literature “DH.4″ refers to the British built, original version of the plane; “DH-4″ to the American built plane with the “Liberty” engine.

22 See the roster on pp. 4–6 of “11th Squadron,” which has this group arriving on September 12, 1918. Other sources indicate they arrived on September 9, 1918; see, for example, Tyler, Selections from the Letters and Diary, diary entry for September 9, 1918 (p. 125).

23 On Heater, see Skinner, “Commanding the 11th.” On the decision to use larger formations, see Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p. 371.

24 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 106–08, provides an incomplete and rather confusing account of that day’s missions, which can be somewhat clarified by the respective raid reports of the 11th and 20th Squadrons (“11th Squadron,” pp. 67–68, and “History of the 20th Aero Squadron, 1st Army,” pp. 218–19.) Both Rath and Coates’s log book list Yates as Coates’s observer; Morgan apparently errs in writing that it was Thrall, who in any case did not join the 11th until October 1, 1918 (“11th Squadron,” p. 5).

25 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., pp. 159, 161.

26 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 110–11.

27 See Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 111–12, and the raid report on p. 71 of “11th Squadron”; there is a third brief account of the raid on p. 55 of Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive]. The three reports do not agree in some respects (times of departure and return, number of planes, place bombed), and such discrepancies occur in accounts of subsequent missions in these documents.

28 Coates, log book; Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 121.

29 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” passim.

30 Ibid, pp. 133–34.

31 Ibid., p. 135.

32 “11th Squadron,” p. 82.

33 “General Orders, Air Service, First and Second Armies, American Expeditionary Forces, Confirming Air Service Victories over Enemy Aircraft,” p. 123 (also Sherman, Operations of Air Service, First Army from August 10th to November 11th, 1918, p. 88).

34 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations, p. 149.

35 Ibid. The 11th’s raid report for this mission describes an encounter with eighteen enemy aircraft, “Fokkers, Pfalz and Albatros” (see p. 89 of “11th Squadron”); the operations report simply records “E.A.”. The entry for Coates in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield, refers to “18 Fokker DVIIs.”

36 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 175.

37 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 182.

38 Morgan, “From Lodgepole to Stenay.”

39 Ferko, “Jagdflieger Friedrich Noltenius,” p. 340. Update, January 23, 2025: Burial cards for Coates, Thrall, Gatton, and Bures have been digitized and can be viewed at the National Archives and Records Administration (and, behind a pay wall, at Fold3.com). Gatton and Bures were initially buried in isolated graves near Carignan, while Coates and Thrall were buried together somewhat further south. This would suggest that the passage cited above is an account of Noltenius’s shooting down of Gatton and Bures, whereas an earlier passage recounting the downing of a “D.H.12” is his accout of shooting down Coates and Thrall.

40 Franks et al. also for this same date credit Noltenius with a DH-9 near Carignan. One should perhaps not ascribe too much importance to the distinction between a DH-4 and a DH-9, as they were difficult to tell apart, particularly in the heat of battle. Noltenius himself (unless this is a transcription or translation error) writes of D.H.12s (!) in the November 4, 1918, encounter. Update January 23, 2025: see preceding note. The DH-9 may well have been the DH-4 flown by Gatton and Bures.

41 I take “Cheveney le Château” to be Chauvency-le-Château, about two miles west of Montmédy.

42 “Confirmed Victories 11th Aero Squadron.”

43 “Americans Killed and Wounded on the French Front” (January 11, 1919).

44 Crites, “Lloyd E. Thrall.” Note: Lloyd Thrall’s middle name, as it appears in the signature on his draft card, could be read as “Etton.” However, the name “Elton” appears frequently as a first and middle name in his family.

45 See “Dead Aviator at Last Known”; the identity search is also recounted in Demobilization by Crowell and Wilson, pp. 90-91. On Loren R. Thrall’s graduation from ground school, see Kroll, Kelly Field in the Great World War, p. 176.

46 Crites, “2LT Loren R. Thrall.”

47 See “Dana E. Coates.”

48 See Sewell and Palin, U.S. World War I Mothers’ Pilgrimage, 1929, record for Mrs Amanda B Coates; and Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957, record for Amanda B Coates.