(Iron River, Michigan, March 11, 1893 – November 7, 1966, Milwaukee, Wisconsin).1

Oxford and Grantham ✯ Thetford, London Colney, Shoreham ✯ France ✯ London and home

Both of Morrison’s parents were from New Brunswick, Canada; his grandfather Morrison had arrived in Canada from Perthshire, Scotland, as a small boy. Morrison’s mother, born Clara Olive Waters, was descended from a Loyalist from New Jersey who, along with his wife, a sister of John Jacob Astor, relocated to Canada in 1783. Morrison’s father, Finlay A. Morrison, and mother apparently came independently from New Brunswick to the U.S. They married and settled in Iron River on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan where Finlay A. Morrison established the Morrison Mercantile Company. There were five children, three boys and two girls; Finley Austin Morrison was the middle child.2

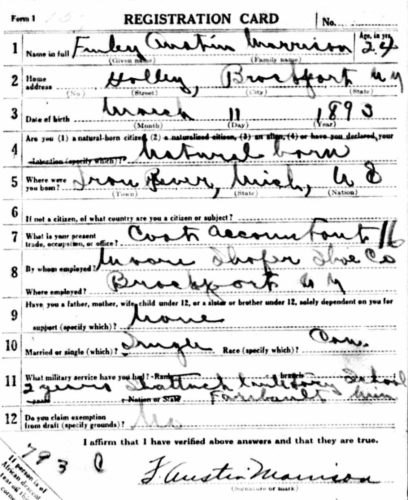

Morrison attended the Shattuck Military School in Faribault, Minnesota, from about 1910 to about 1912 and then went on to the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, graduating in 1916.3 When he registered for the draft in June 1917 he was living in Brockport, New York, and working as a cost accountant for the Moore Shafer Shoe Company.4 He enlisted in the reserve corps at Buffalo, N.Y., on July 7, 1917, and went on to attend ground school at Cornell’s School of Military Aeronautics in the class that graduated September 1, 1917.5

Most of the eighteen men from Morrison’s ground school class chose or were chosen to continue their training in Italy and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed from New York for Europe on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania. After a brief stopover at Halifax the Carmania joined a convoy for the voyage across the Atlantic. The men sailed first class and enjoyed some leisure, including concerts featuring the violinist Albert Spalding, who was on board. They also had Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, and, once they entered dangerous waters, they took turns at submarine watch.

Oxford and Grantham

When the ship docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment members learned that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England for their training. They travelled by train to Oxford, where they attended ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics.

In early November twenty men were selected by Elliott White Springs, who was in charge of the cadets (as they were now called), to begin flight training at Stamford. Places at training squadrons were in short supply, so the remaining men, including Morrison, were ordered to a machine gun school, Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire. When not doing course work or practicing on the range, the men explored the countryside and nearby towns. An entry in War Birds for November 12, 1917, recalls that “Well, the old man is himself again. [John Hurtman] Jack Fulford, Cal [Laurence Kingsley Callahan], Morrison, [John Warren] Leach and I went to Nottingham over the week-end. We didn’t get very drunk.” And, at no small expense, the men were obliged to outfit themselves in a manner that satisfied their American and British superiors: “Morrison came in to-night with a beautiful bun and a new pair of boots. They were tight too and it took four of us to pull them off.”6

Thetford, London Colney, Shoreham

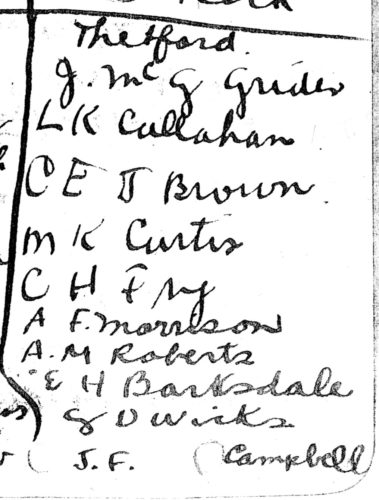

In mid-November it was announced that there were fifty places at training squadrons, and Morrison was among those selected to fill them. He and nine others were assigned to Thetford in Norfolk.7 Five went to No. 12 Training Squadron, and five—Morrison, Eugene Hoy Barksdale, Alexander Miguel Roberts, Glenn Dickenson Wicks, and Jesse Frank Campbell—to No. 25 T.S. According to Barksdale, he, Morrison, Roberts, and Wicks roomed together at Thetford.8

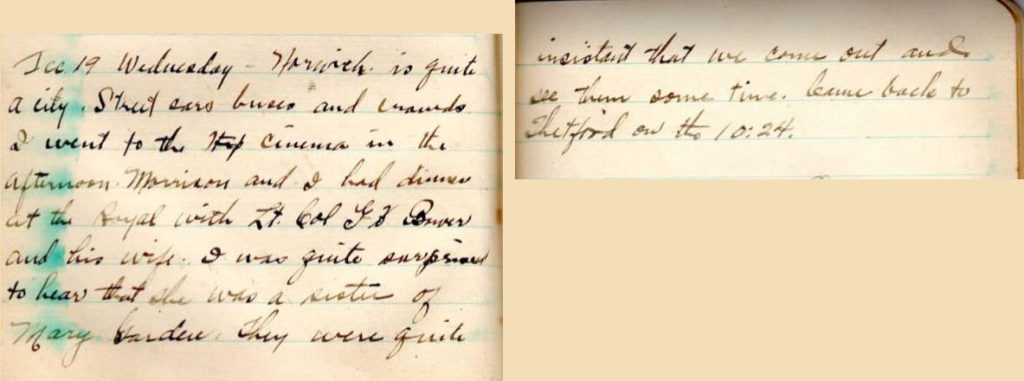

The training plane used at No. 25 T.S. was the Maurice Farman S.11, nicknamed “Rumpty” or “Rumpety,” a “pusher,” i.e., with the propeller behind the cockpit.9 Winter wind, rain, and snow meant there were many days with no flying, but Barksdale was able to make a first flight on November 30, 1917, and Morrison presumably began flying at around the same time, initially dual, but, assuming his training proceeded along the same lines as Barksdale’s and Jesse Campbell’s, solo before Christmas.10 On December 19, 1917, Morrison joined Campbell in an outing to Norwich, where they “had dinner at The Royal with Lt. Col G[eorge] H[addon] Bower and his wife.”11 Campbell does not indicate how it came about that they dined with an officer of the Black Watch (Royal Highlanders), who invited him and Morrison to visit; Campbell, and presumably Morrison, was impressed that Bower’s wife was the sister of Mary Garden, a well-known operatic soprano.

From Thetford, Morrison was posted to London Colney and No. 74 T.S. The date of his posting is uncertain, but, if his course continued to resemble Barksdale’s and Jesse Campbell’s, it was before the turn of the year. James Ira Thomas Jones (“Taffy” Jones) was there and recalled the influx of Americans: “Our school was lucky enough to get such grand types as Ken [sic] Curtis . . . Fred Stillman, Alexander Roberts, Clarence Fry, H. G. Shoemaker, C. Matthiessen, W. V. [sic] Wait and A. F. Morrison.”12

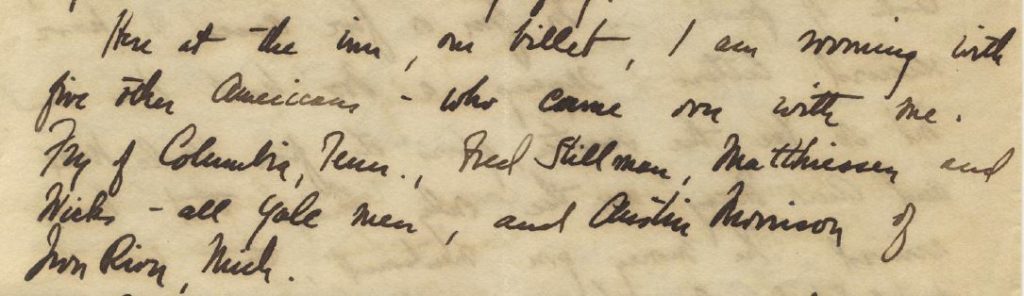

The London Colney aerodrome and accommodations were in general primitive, but some of the American cadets were lodged at the Red Lion in nearby Radlett where, as Marvin Kent Curtis wrote his sister, they were “more comfortably settled than at any other place I have been in the R.F.C. . . . I am rooming with five other Americans who came over with me, Fry of Columbia, Tenn., Fred Stillman, Matthiessen and Wicks—all Yale men, and Austin Morrison of Iron River, Mich.”13

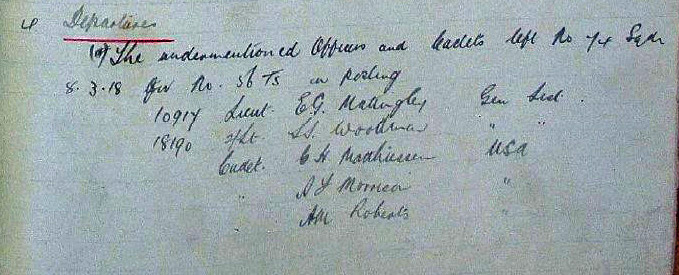

At 74 T.S. Morrison would have trained on Avros, again initially dual and then solo. By mid-February he was ready to do the requisite cross country flight which typically consisted of flying south via Northolt to Hounslow and back.14 Jesse Campbell noted in his diary on February 17, 1918, that “Morrison, Matheson [sic], and Roberts did their cross country this afternoon and came back in fog.” Presumably not long after this Morrison moved on to training on Sopwith Pups and completed the other requirements to graduate from this stage of R.F.C. training. On March 8, 1918, he, along with Matthiessen and Roberts, moved to No. 56 T.S., across the field at London Colney from No. 74. No. 74 became an operational squadron preparing to go to France in early March, and the Americans in training were reassigned.

On March 6, 1918, Pershing forwarded the recommendation for Morrison’s commission to Washington; approval came back on March 17, 1918, and Morrison was placed on active duty on March 29, 1918.15 It appears that he was then at Shoreham-by-the-Sea.15a Morrison’s fellow second Oxford detachment member George Augustus Vaughn was posted there at about the same time. In a letter home, Vaughn wrote that “I don’t know yet why I am here, so I am just wandering around until I can find out from Headquarters. I was expecting to go to Scotland . . . I expect my stay will be very short. . . .”15b And, indeed, Vaughn proceeded almost immediately to Ayr. This would seem to make sense, given that the training squadron at Shoreham (No. 3) is described as intended for training “pilots from scratch”and thus no longer relevant for Vaughn or Morrison.15c And yet the planes at Shoreham included Pups, Camels, and S.E.5s, suggesting that Morrison could have put in useful time there.15d Morrison’s friendship with a Shoreham family (about whom more below) certainly suggests a prolonged stay. Whether he, like Vaughn and others, eventually went on to either Ayr or Marske for advanced training is not evident from the sources available to me.

France

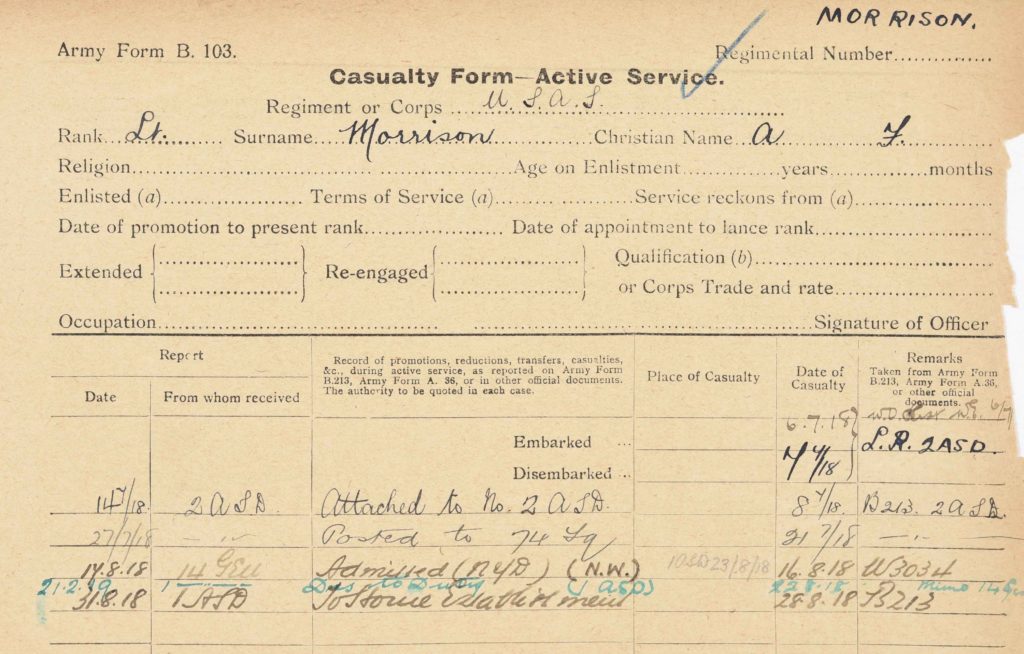

In early July 1918 Morrison was posted overseas. His casualty form, a record of active service postings, puts him at “No. 2 ASD” on July 8, 1918, i.e., at the pilots pool at Rang du Fliers, near Boulogne, part of the No. 2 Aeroplane Supply Depot.16 Matthiessen had arrived the preceding day.17 Like many others, they had to kick up their heels there for a while, but eventually, on July 21, 1918, they were assigned to No. 74 Squadron R.A.F.—which meant they were back with many of the men they had trained with at London Colney.18 (Their fellow second Oxford detachment member, Roberts, had also been with No. 74, but had two days previously been shot down and made a prisoner of war.)

No. 74 Squadron flew S.E.5a’s and was stationed from April through September 1918 at Clairmarais near St. Omer, initially at Clairmarais Nord and then, from early August at the newer aerodrome, Clairmarais Sud, about a mile away.19 The squadron, commanded by Keith Logan Caldwell (“Grid” Caldwell), was part of the 11th (Army) Wing, II Brigade, attached to General Sir Herbert Plumer’s Second Army; the Second Army front ran approximately from Houthulst Forest ten miles south to Ypres and from Ypres twenty miles southwest to Nieppe Forest.20

From the Clairmarais aerodromes the pilots of No. 74 Squadron flew line and offensive patrols, as well as, occasionally, escort, ground strafing, and wireless interception missions, all the while seeking to put enemy reconnaissance planes out of commission and to eliminate enemy scouts flying over and east of the Second Army front north and south of Ypres—all this is apparent from the account of No. 74 Squadron provided by Ira Jones in his Tiger Squadron. As with a number of other squadrons, the squadron record book and other relevant original documents appear not to have survived, and I can thus not provide details of Morrison’s activities before August 7, 1918. Jones in his account of that day reports that “Morrison crashed and hurt himself on the aerodrome. He’s gone to hospital.”21

There appears to be no incident casualty card for this crash, but according to other records, Morrrison was flying S.E.5a C9585 on an offensive patrol when the engine failed, forcing him to crash land near the aerodrome.22 His initial hospitalization was perhaps at a facility near Clairmarais; his casualty form, as well as a personal casualty card for him, indicates that he was admitted “N.Y.D.” (not yet diagnosed) to No. 14 General Hospital at Wimereux near Boulogne on August 16, 1918. The casualty form indicates he was then discharged to No. 1 A.S.D. at Marquise on August 22, 1918, and from there was sent back to England on August 28, 1918.23

London and home

That same day, August 28, 1918, Morrison’s fellow second Oxford detachment member Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, working at American Aviation H.Q. at 35 Eaton Place in London, wrote in his diary that “Morrison came in. He is back from France and has had to wash out flying. He has had a talk with Capt. [P. L.] Foster and is going to be under him” (Foster was aviation purchasing officer at H.Q.).24 “We are going to try and get an apartment together.” They succeeded, finding a flat apparently on Ebury Street in Belgravia not far from 35 Eaton Place: “It is a peach. Wonderfully furnished, a phone etc and four big rooms. . . . Morry is going to move in on Sunday as he is now at a hotel.”25 Complications arose, but they were able to move in in mid-September 1918, and they continued to share these rooms until the end of the war.26

Milnor provides few details about Morrison’s work at H.Q., but often notes when they dined out together and with whom: with Milnor’s boss Geoffrey James Dwyer, with Matthiessen and his friend Frederic Ernest Luff (“Freddy”), who had also been in No. 74 Squadron, and with unnamed American nurses, one of whom was from Morrison’s home town.27

Morrison, and Milnor, also spent a good deal of time with Morton Lewis Cook and his wife Kate Cook, née Stancombe, who resided in Shoreham and operated a factory that made jam, marmalade, and chutney. Milnor refers to Mr. and Mrs. Cook as Morrison’s “adopted” parents. Immediately after moving into the flat on Ebury Street, Morrison spent the weekend with the Cooks, and he took Milnor with him when he went to Shoreham again the first weekend of October. At “Campsie,” the Cooks’ home, the two men slept late, played bridge, and enjoyed the rather sumptuous home cooking—Mrs. Cook excelled in domestic skills, very much living up to her married name. “Ma” and “Pa” Cook came up to London the following week and, after trying in vain for rooms at several hotels, ended up staying with Morrison and Milnor—and procuring theater tickets for them three evenings in a row: “Chu-Chin-Chow,” “By Pigeon Post,” and “Roxana.” Milnor and Morrison each visited the Cooks again separately. Morrison went down to Shoreham on November 8, 1918, arriving back at the London flat on the 10th. Milnor had just heard the news that the Kaiser had abdicated.28

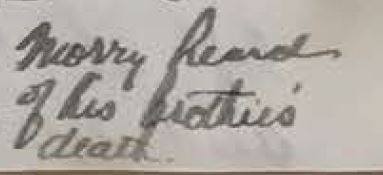

The trip to Shoreham and the end of the war were shadowed for Morrison by news he received on November 4, 1918.29 His older brother Joel Royden Morrison, a soldier at Camp Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky, had died of influenza on October 21, 1918.30

Morrison was able to return to the U.S. in December 1918, travelling in the same “casual officers” group on the Celtic as Paul Stuart Winslow of the first Oxford detachment and John Owen Donaldson, who, with second Oxford detachment member Robert Alexander Anderson, had managed to escape from a P.O.W. camp; Clarence Bernard Maloney, also of the second Oxford detachment, was on board as well.31

After the war Morrison was employed in various businesses and moved about a good deal. He worked in Tokyo and Korea after World War II and in 1953 was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Truman for his work in Korea.32

mrsmcq September 24, 2020; revised October 26, 2022, to reflect new information on Shoreham

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Morrison’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Fauley [sic] Austin Morrison. His place and date of death are taken from “Father of Local Resident Dies.” In some documents, Morrison appears as Austin Finley Morrison. The photo is taken from p. 107 of Michiganensian 1916.

2 On Morrison’s family, see records available at Ancestry.com and Sawyer, A History of the Northern Peninsula of Michigan and its People, vol. 2, pp. 963–64. Morrison’s father’s first name is generally given as “Finlay,” while Morrison is usually “Finley.”

3 See Morrison’s draft registration, cited above, and Michiganensian 1916, p 107.

4 See Morrison’s draft registration, cited above.

5 See Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917–1919, record for Austin Finley Morrison, and “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

6 War Birds, November 9, 1917. “bun,” i.e., inebriated.

7 Foss, diary entry for November 15, 1917.

8 Barksdale, diary entry for November 18, 1917 [sic; sc. November 19, 1918?].

9 Jesse Campbell, diary entry for November 20, 1917.

10 Barksdale’s and Jesse Campbell’s diaries, passim.

11 Jesse Campbell, diary entry for December 19, 1917.

12 Ira Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 60

13 Curtis, letter of January 19, 1918.

14 Ira Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 61.

15 Cablegrams 691-S and 936-R; McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205,” where for “Morrison, A. E.” read “Morrison, A. F.”

15a See Biddle, Special Orders No. 35, where Morrison is described as being placed on active duty at Shoreham on April 29, 1918, which is almost certainly an error and should be March 29, 1918.

15b Vaughn, War Flying in France, letter of March 31, 1918.

15c Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 251.

15d See Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 297; also pictures of planes at No. 3 T.S. on pp. 36-37 of Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial”; and recall that Roy Olin Garver was flying a Camel out of Shoreham when he was killed at the end of January 1918.

16 See “Lieut. A F Morrison USAS.”

17 See “Lieut. C H Matthiessen.”

18 See “Lieut. A F Morrison USAS” and “Lieut. C H Matthiessen.”

19 On the sites of the World War I Clairmarais aerodromes, see O’Connor, Airfields and Airmen of the Channel Coast, Chapter 3, and “Aérodromes britanniques situés dans le Pays de Saint-Omer.” From these sources it appears that the aerodromes were about three and a half miles east of the village of Clairmarais, on the eastern edge of the Forêt de Clairmarais.

20 This is the description of the Second Army front in the late spring and summer of 1918 provided by Blanford, “Sans Escort,” part 1, p. 147.

21 Ira Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 165.

22 Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, and Pentland, Royal Flying Corps. Henshaw and Pentland base their accounts on entries in documents in The National Archives (UK): Pilot and observer casualties: R.F.C. France, and Reports on aeroplane and personnel casualties.

23 For the casualty form, see “Lieut. A F Morrison USAS”; for the casualty card, see “Morrison, A.F.”

24 On Foster’s position, see “A History of the Air Service in Great Britain,” p. 209. I have not been able to identify Foster further, beyond his initials.

25 Milnor, diary entry for August 30, 1918.

26 Milnor, diary entry for September 15, 1918.

27 Milnor, diary, passim.

28 Milnor, diary, passim.

29 Milnor’s diary entry of that date.

30 Ancestry.com, Kentucky, Death Records, 1852-1965, record for Joel R Morrison.

31 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Austin F. Morrison; record for Clarence B. Maloney.

32 “Morrison Gets Merit Citation.”