(Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, November 9, 1896 – Riverside, California, June 19, 1992).1

Dixon was the only son of Anna Elizabeth, née Dietrich, and Charles Henry Dixon, a Pittsburgh real estate executive who died in 1914.2 On his father’s side, Dixon’s family had lived in Pennsylvania for several generations; his mother’s father had emigrated from Alsace and married a woman of German descent.3 Growing up, Dixon lived with his parents and his maternal aunt and uncle; the uncle, August A. Frauenheim, was a prominent manufacturer and banker in Pittsburgh.4

Dixon attended Princeton (class of 1920). He was a student at the privately funded Princeton Aviation School, which had been established in the spring of 1917 to train Princeton students, and then at the government-run Princeton School of Military Aeronautics which superseded the Aviation School in June 1917. Dixon’s Princeton S.M.A. ground school class graduated August 25, 1917.5 He was one of the men from this group selected for training in Italy and thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “Second Oxford Detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917. At Halifax, the Carmania joined a convoy and set out on the Atlantic crossing September 21, 1917. When the ship docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men learned, to their initial but not lasting dismay, that they would not go to Italy but to Oxford, where they would repeat ground school. While at Oxford, Dixon palled around with fellow second Oxford detachment member Fremont Cutler Foss, and they apparently roomed together at Queen’s College.6

In early November most of the men were sent to Harrowby Camp near Grantham to attend machine gun school. Because his Princeton time had included some actual experience in the air, Dixon was among the twenty men selected by Elliott White Springs to go to flying school at Stamford rather than to Grantham.

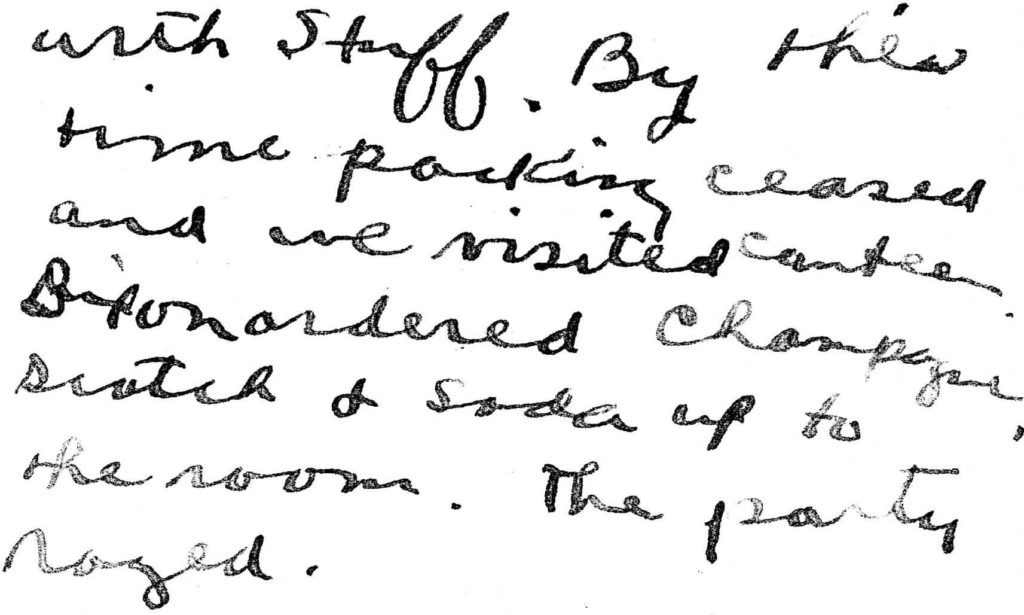

Dixon ordered champagne and scotch and soda as part of a bibulous farewell to his friends and fellow detachment members Foss, Perley Melbourne Stoughton, Leo McCarthy, and Donald Swett Poler the evening before their November 3, 1917, departure for Grantham.7 Dixon himself and the nineteen other men remaining left for No. 1 Training Depot Station, Stamford, on November 5, 1917. Two days later, he, along with Walter Chalaire, Arthur Richmond Taber, and “a number of the other boys at Stamford came down to see” the men at Grantham.8

Dixon’s R.A.F. service record provides no information about his training after Stamford, and Dixon himself, quoted by Marvin L. Skelton, remarks only that there “followed a series of schools in flying training all over England and Scotland and I became a Sopwith Camel pilot with fifty hours solo on various training aircraft—twelve hours on Camels at combat school.”9 The “combat school” was presumably the School of Aerial fighting at Ayr, Scotland, where he was stationed when he was placed on active duty on April 6, 1918.10 Dixon had completed sufficient training by early March to be recommended for his commission; Pershing’s cable forwarding the recommendation to Washington is dated March 7, 1918. The confirming cable is dated March 17, 1918, but it was another three weeks before he was placed on active duty.11 Dixon was one of many cadets frustrated by the slow pace of the military bureaucracy. He later recalled that “delayed (U.S. Army) commissions prevented the Royal Flying Corps from sending us out to overseas pools so we were assigned temporarily to ferry piloting planes overseas.”12

On May 23, 1918, Dixon, along with fellow detachment member William Joseph Armstrong, was posted to the R.A.F. and, the next day, to No. 209 Squadron R.A.F., a Camel squadron stationed at Bertangles a few miles north of Amiens—which city, as a result of the first phase of the German Spring Offensive, was now only about ten miles from the front.13 Dixon recalled that “the German advance lines were then too near for comfort.”14 Leonard Joseph Desson was already at 209, and Bradley Cleaver Lawton, also of the second Oxford detachment, arrived around the same time.14a

Dixon later recalled that “May 25th, I began flying at 209 Squadron with my own Camel. My first assignment was shooting at a ground target.”14b According to the squadron record book, he flew D3328 during the fifty-minute flight that evening.14c He had another practice flight on May 27, 1918, and on May 28, 1918, he flew the first of many aerial sentry patrols, some between Amiens and the aerodrome, some along the road between Amiens and Abbeville to the northwest. All these patrols were uneventful—except insofar as flying at great height with no oxygen and inadequate protection against the cold was memorable. On June 9, 1918, flying Camel D3327, he patrolled at 20,000 ft. between Amiens and Abbeville.

The next afternoon he was assigned to join Cedric Nevill Jones and Leslie Campbell Story in a “Spec Miss intercept WEA.” A “W.E.A.” mission involved going after enemy observation aircraft near the lines whose wireless signals had been intercepted and used to determine their location.14d On June 10, 1918, the three pilots evidently flew as far as Méricourt-sur-Somme, about sixteen miles due east of Amiens, at which point Story’s engine cut out; he managed to get back across the lines to make a forced landing in friendly territory. Jones and Dixon (in B6371) continued flying, but saw no enemy aircraft.

Dixon’s next flight was not until June 13, 1918, when he, again flying B6371, and Jones made an hour-long special patrol in the late evening; the record book does not indicate the location. Around this time influenza hit the squadron, and for a time nearly half the men were in hospital. There is no notation of illness on Desson’s casualty form, but the fact that his name is absent from the record book between June 13 and June 24, 1918, suggests that he, too, had succumbed.

On the latter date, June 24, 1918, Dixon participated in his first high offensive patrol—his last flight with 209. He again flew B6371 and was part of a six-plane formation. The other pilots were Jones, Story, John Henry Siddall, Edward Barfort Drake, and James Andrew Fenton. They carried bombs and dropped them on Méricourt-sur-Somme and on woods east of the village; the mission lasted two hours.

Soon after this flight, Dixon, along with Armstrong, Desson, and Lawton, was ordered to join the U.S. 17th Aero Squadron (also flying Camels) at Petite Synthe on the coast near Dunkirk, about seventy miles north of Bertangles. Arriving on or about June 26, 1918, they joined a number of other members of the second Oxford detachment already assigned there.15 The 17th, along with the 148th, was American in personnel, but stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until late in the war, when they were moved south to the American front.

Dixon was assigned to B flight, commanded initially by Weston Whitney Goodnow of the second Oxford detachment, and then, from early July, by William Dolley Tipton of the first Oxford detachment.16 The 17th took about three weeks to get to know their equipment and their territory while working on formation flying. Dixon recounts how “after a few weeks of training on the LeRhones [Sopwith Camels with Le Rhône engines] . . . we were ready to escort the D.H.9 bombers over Bruges docks, about a twice weekly basis. Many of these D.H.9s were manned by U.S. pilots, most of them U.S. Marines. We flew over the U.S. bombers at about 15,000 feet.”17 These escort flights began July 20, 1918; the pilots of the 17th had begun line and offensive patrols along the relatively quiet Nieuport to Ypres front five days previously.18

During late July and early August 1918 plans for an attack on the large enemy aerodrome at Varsenare, a few miles west of Bruges, were being made, and the 17th Aero, despite having recently lost several pilots to leave, illness, injuries, and death, joined R.A.F. squadrons in this successful mission on August 13, 1918. Dixon’s B flight at the start of the raid consisted of but three pilots—himself, Rodney Daniel Williams, and William Hugh Shearman—and, when mechanical problems forced the leader, Williams, to turn back, only two.19 Shearman and Dixon got separated, and Dixon “lost patrol and being unable to locate it dropped four bombs on Ostend from 6000 feet” before returning to Petite Synthe.20

On August 17, 1918, the 17th moved south from Petite Synthe to the (British) Third Army area, specifically, to Auxi-le-Château northwest of Doullens, in preparation for what became known as the Second Battle of Bapaume.21 They were again to escort R.A.F. bombers, but also to do bombing and strafing, starting August 23, 1918. Dixon participated in two raids on that day, targeting transport southwest of Bapaume. The next day the pilots went out in pairs; in the evening Dixon and Robert Miles Todd dropped bombs, and Dixon shot at transport northeast of Bapaume as the Third Army drove the Germans towards Cambrai.22

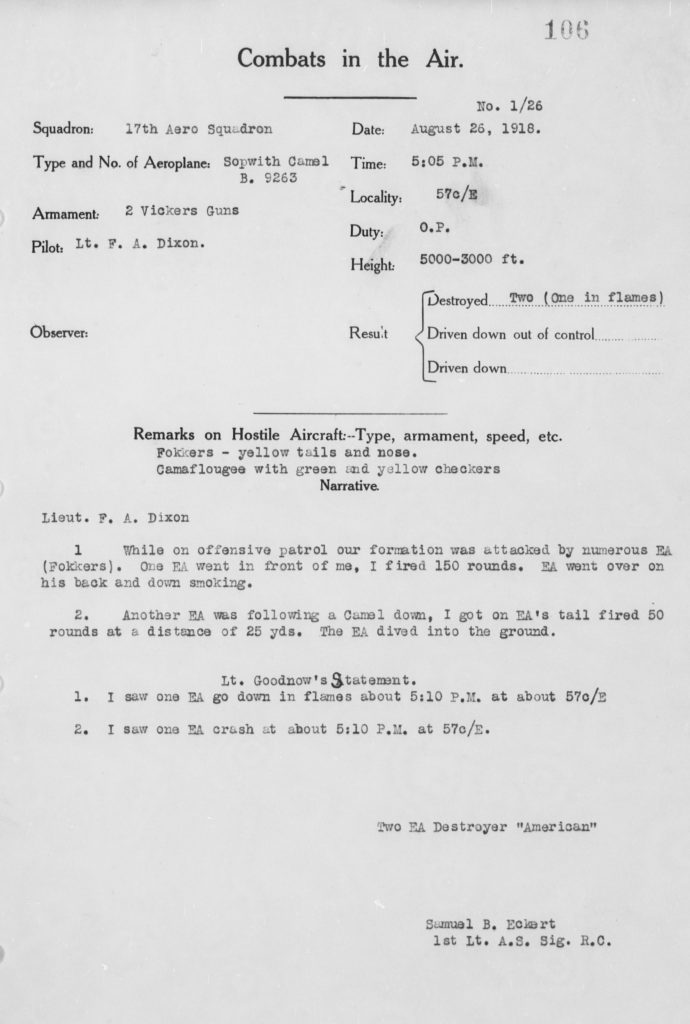

The Germans recognized that their retreating troops needed better air cover and moved experienced squadrons in. Thus, on August 26, 1918, when a patrol from the 17th flew to assist pilots of the 148th (who had been ordered out despite severely unfavorable weather), they encountered a swarm of Fokkers over the Bapaume-Cambrai road. Of the nine Camel pilots from the 17th, three (Harry Helmer Jackson, Jr., Howard Paul Bittinger, and Laurence Roberts) were killed in action; one (Henry Bradley Frost of the second Oxford detachment) died that night, and two (Tipton and Todd) were captured. Goodnow and Ralph William Snoke returned, followed, a distant third and last, by Dixon. Despite being severely outnumbered, the 17th downed a number of the enemy aircraft, including two to the credit of Dixon.23

After the losses on the 26th, the crippled 17th Aero Squadron was given a breather as they tried to figure out how to reorganize at half strength. Dixon was offered the position of deputy flight leader of B flight, but turned it down. He had just had to crash land during a practice flight because one of his landing wheels had fallen off, and this incident helped him make up his mind to go ahead and take his scheduled leave in England rather than accepting the position.24

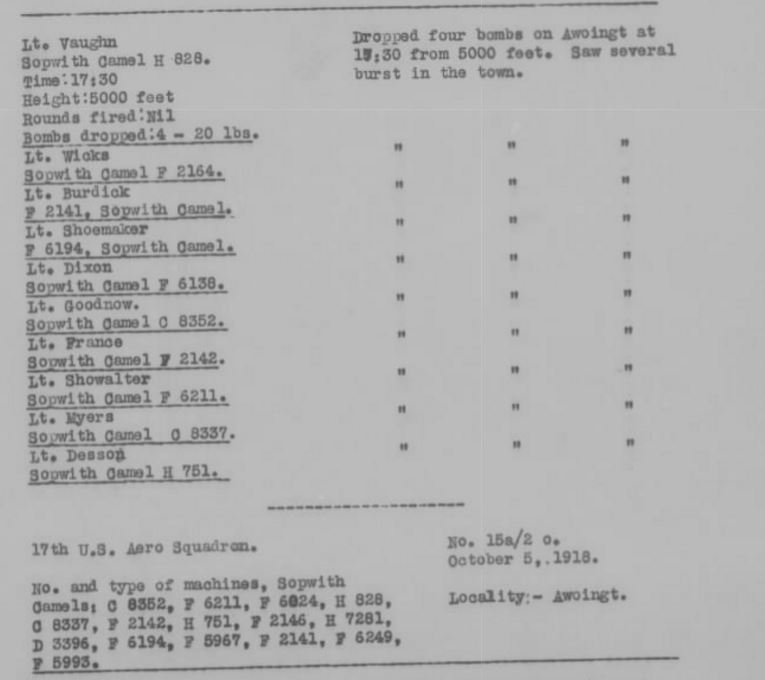

A third of the way through September 1918 the 17th Aero was ordered to move once again, this time to Soncamp Aerodrome, about fifteen miles east of Auxi-le-Château. Offensive patrols began the day of their arrival, September 20, 1918. B flight, Dixon’s flight, now led by his fellow second Oxford detachment member George Augustus Vaughn, went out on September 21 and 22, 1918; Dixon was able to confirm two Fokkers to Vaughn’s credit on the 22nd.25 When two more pilots (Glen Dickenson Wicks & Harold Goodman Shoemaker) were lost from B flight on October 5, 1918, Dixon was moved up to deputy flight leader.26 In addition to offensive patrols in September and early October, Dixon also flew numerous bombing raids, sometimes as many as three a day, through mid-October 1918, the targets moving farther to the east as General Byng’s drive to take Cambrai progressed and succeeded.

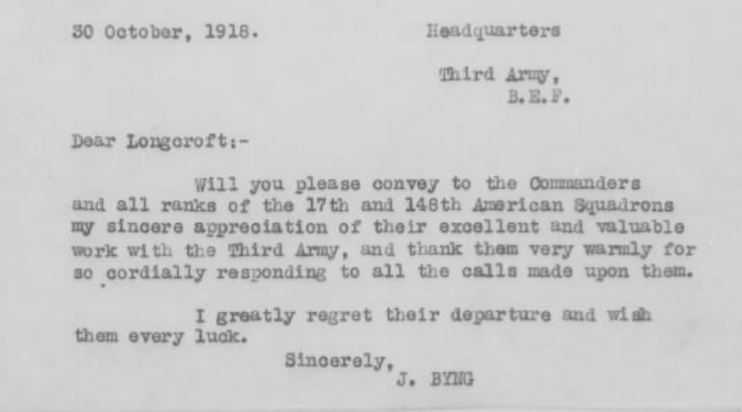

Towards the end of October word was received that the 17th was to move to the American sector; a short but affecting message of thanks from Byng for their assistance to the Third Army was read.

On November 1, 1918, they began the train journey south, arriving, finally, near Toul on November 4, 1918. Here Dixon got in some practice on Spads and celebrated the armistice; he was present when photos were taken of the 17th and the 148th. He then went to Issoudun to await transport home.27 He and Goodnow were part of a group of officers who sailed from Brest on the Ortega on February 7, 1919, arriving at New York on February 19, 1919.28 Five days later, Dixon was honorably discharged.29

Dixon resumed his studies and graduated from Princeton in 1921. He was employed by Western Electric; he returned to the military during World War II.30

mrsmcq June 26, 2017

Revised February 26, 2019, to reflect 209 Squadron record book

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Dixon’s dates of birth and death and place of death, see Ancestry.com, California, Death Index, 1940-1997, record for Frank Aloysius Dixon. For his place of birth, see Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917-1919, 1934-1948, record for Frank Aloysius Dixon. The photo is a detail from a photo taken by Orren Jack Turner of the Princeton School of Military Aeronautics ground school class that graduated August 25, 1917.

2 See “Charles H. Dixon.” Frank Dixon’s Pennsylvania veteran’s compensation application record, cited above, provides his mother’s maiden name.

3 See Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1963, record for Francois Dietrick [sic]; and Ancestry.com and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1880 United States Federal Census, records for Francis and Barbara Deitrich [sic].

4 See Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Frank A Dixon; and Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Frank A Dixon. On Frauenheim, see The Book of Prominent Pennsylvanians, p. 178.

5 See The Princeton Bric-a-Brac 1919, p. 86, and “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

6 Foss, Diary, entries for October, passim.

7 Foss, Diary, entry for November 2, 1917.

8 Foss, Diary, entry for November 7, 1917.

9 Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon and the 17th Aero Sqdn.,” p. 155.

10 Dixon’s active duty date is given by McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205”; the same date as well as the place are provided by Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

11 Cablegrams 694-S and 936-R. One of the cards for Dixon at Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917–1919, 1934–1948 indicates that he was commissioned on April 4, 1918. (In filling out the “Veteran’s Compensation Application,” also at Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania . . ., Dixon optimistically recalled the date as March 16, 1918.) See preceding not regarding his active duty date.

12 Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon and the 17th Aero Sqdn.,” p. 155.

13 See the R.A.F. casualty form for Dixon (“Lieut. F A Dixon USAS”), as well as Munsell “Air Service History”, p. 192 (7) for Armstrong, p. 194 (9) for Dixon.

14 Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon and the 17th Aero Sqdn.,” p. 156.

14a See the R.A.F. casualty forms for Desson (“Lieut. Leonard Joseph Desson USAS”) and Lawton (“Lieut. Bradley Cleaver Lawton USAS”), as well as Munsell, “Air Service History”, p. 194 (9) for Desson, and p. 197 (12) for Lawton. Dixon kept two nearly identical group photos of 209 Squadron officers that include himself, Armstrong, and Lawton. See Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 45 and Jones, “As I Remember,” p. 38.

14b Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon and the 17th Aero Sqdn.,” p. 156.

14c Here and in the subsequent description of Dixon’s period with No. 209, information is taken from No. 209 Squadron Record Book (RFC/RAF).

14d W.E.A. is apparently not a widely used abbreviation; it probably stands for “wireless enemy aircraft.” See “RAF abbreviation ‘W.E.A.’—special mission intercepting.”

15 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 156, gives June 26, 1918 as the arrival date for the four men. Munsell, “Air Service History,” indicates, p. 149 (9), that Desson and Dixon arrived June 25, 1918, pp. 192 (7) and 197 (12) that Armstrong and Lawton arrived June 26, 1918.

16 Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon,” p. 158; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 30.

17 Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon,” p. 160.

18 See Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 24; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 35 and 40.

19 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 55.

20 Clapp, A History or the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 98.

21 See Murton Campbell, diary entry for August 17, 1918, for the date of the move, which is unclear from other sources (Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 37; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 64-65; Jones, The War in the Air, p. 469).

22 See Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 98 ff., for bombing reports for this period. See Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 75, on using “units of two.”

23 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 80-83, offer a vivid reconstruction of the events of this encounter. See also Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 74-77, where the combat reports are reproduced, and 40-41 for a narrative account.

24 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 86.

25 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 81-82.

26 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 109.

27 Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon and the 17th Aero Sqdn.,” p. 181.

28 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, passenger list for officers on the S.S. Ortega.

29 Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917-1919, 1934-1948, record for Frank Aloysius Dixon.

30 “Frank A. Dixon ’20.”