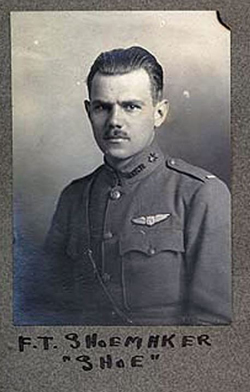

(Mt. Clemens, Michigan, June 26, 1893 – December 26, 1938, Mt. Clemens, Michigan).1

Training in England ✯ The 11th Aero

On his father’s side, one of Fred Trufant Shoemaker’s ancestors was a Thomas Shumacher who emigrated from the Palatinate (Germany) to the Mohawk Valley in central New York in the early eighteenth century.2 The family’s loyalties were divided during the Revolutionary War, but Fred Trufant Shoemaker’s sisters were able to trace their lineage back to Han Yost Shoemaker, the Patriot grandson of Thomas, and thus to qualify as Daughters of the American Revolution.3 Han Yost Shoemaker’s son Robert moved with his young family to Illinois in 1837. Robert’s son, the enterprising Joseph Peter Shoemaker, Fred Trufant Shoemaker’s grandfather, was involved in business and agriculture ventures in Ohio and Kentucky before settling in Michigan.4 His son, Thomas Joseph Shoemaker, married Alice Maud Trufant in Detroit in 1875, and the couple settled in Mt. Clemens, north of Detroit, where he worked variously as a farmer, a liniment manufacturer, and a golf club manager.5 Her father, Emory Bigelow Trufant, was born in Massachusetts, where the Trufants had lived since at least the early eighteenth century; his grandfather was Joseph Trufant, of Weymouth, who served at the captain of an independent company of Massachusetts militia during the Revolutionary War.6

There are four documented children of the marriage of Thomas Joseph and Alice Maud Shoemaker. The older son, Thomas Trufant, was born in 1876, followed by two daughters, Charlotte Trufant and Kate Trufant in 1878 and 1879, and, finally, Fred Trufant in 1893. I find no records relating to the family between the census of 1880 and that of 1900 (the 1890 census is lost), and so cannot tell whether there were children who did not survive or whether there is another explanation for the gap between the older children and the youngest.

Fred Trufant Shoemaker played semi-professional football for a Mt. Clemens team while he attended high school there; he graduated in 1910.7 He did not attend college, but worked for the Nellis Newspapers as an advertising salesman.8 In the summer of 1916 he enlisted in the Michigan National Guard as a member of the Thirty-first Regiment of Infantry and was thus among those posted to El Paso for duty on the Mexican border from June through November of 1916.9 The military life seems to have appealed to Shoemaker; when he registered for the draft he was in the R.O.T.C. at Fort Sheridan in Illinois. He evidently applied to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and was accepted; he was assigned to the School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Illinois. His class graduated September 1, 1917.10

There was much speculation about where graduates from this ground school class would go for actual flying training, with information and plans changing frequently. The initial understanding, according to Shoemaker’s classmate, Vincent Paul Oatis, was that the men would “go to Rantoul [Illinois] to the aviation field and pursue the actual flying game from three to four months.”11 However, in mid-August 1917, again according to Oatis, there was a request for volunteers “who would like to go to Italy for their air training. Right now Italy is about the best in the world in flying, so I grabbed at it and applied. Nearly everyone in our squadron did likewise.”12 After some further confusion as to whether some of those who had signed up might go to France instead, all but five of the approximately thirty men in this Illinois S.M.A. class, including Shoemaker, became part of the detachment that set out from New York on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania, bound for Europe on the understanding that they, the 150 cadets of the “Italian detachment,” would learn to fly in Italy.

Training in England

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, there was another change of plans: the men were not to go on to Italy but to remain in England and, even worse, as it seemed, to go through ground school all over again. They travelled by rail to Oxford and Oxford University where the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics was located. The “Italian detachment” became the “second Oxford detachment”—a first detachment of fifty American pilots in training having arrived there a month earlier. The men made the best of their second round of ground school and in retrospect recognized the benefits of R.F.C. training. Their British instructors, unlike those in the U.S., had had war flying experience, and this added considerable interest to the course work. Since the men had already covered much of the material, they did not have to study especially hard, and they enjoyed Oxford hospitality and explored the town and surrounding countryside.

The men were initially assigned rooms either in Christ Church College or The Queen’s College, but, about three weeks into their stay, in the aftermath of some high spirited and bibulous celebrations, the British insisted on moving all the Americans into a single college, Exeter. According to the entry for October 22, 1917, in War Birds: “We have the whole college to ourselves. There are a million rumours flying around about what is going to happen to us. The Colonel [Bertram Richard White Beor, C.O. of the Oxford S.M.A.] sent over one of his staff officers to help . . . . He and big Shoemaker, who used to drive a dogteam in Alaska, are great friends and I foresee trouble.” This is the first of two references connecting Shoemaker to Alaska; I have found no documentation that would provide more background.

The men were eager to start learning to fly, but disappointment was in store for most of them at the end of four weeks at Oxford. The R.F.C. was able to accommodate twenty men from the detachment at No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford in early November, but the others, including Shoemaker, set out on November 3, 1917, for Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend a machine gun course at Harrowby Camp. As Parr Hooper, also sent to Grantham, remarked: “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”13

At Grantham the men spent two weeks learning about and practicing with the Vickers machine gun. As at Oxford, they used some of their time off to explore the surrounding area. John McGavock Grider, from the ground school class a week ahead of Shoemaker at Illinois, kept a photo showing himself and others who had been at the Illinois S.M.A., including Shoemaker, setting out for Nottingham, the nearest large town. Shoemaker is noticeably taller than the others—references to him often mention his height and heft, and he was, of course, given the nickname “Tiny.”14

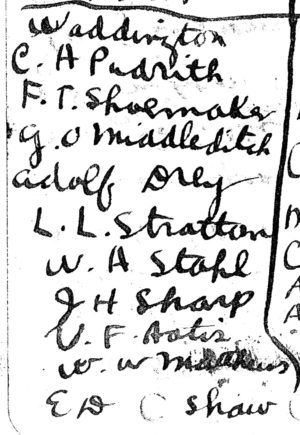

In mid-November, it was determined that there was room at training squadrons for fifty of the men, and Shoemaker was among those selected. Along with nine others (Adolf M. Drey, William Wyman Mathews, George Orrin Middleditch, Oatis, Chester Albert Pudrith, Joseph Hiserodt Sharpe, Walter Andrew Stahl, Lynn Lemuel Stratton, and Ervin David Shaw), he set off on November 19, 1917, for Waddington (about twenty miles north of Grantham) where several R.F.C. training squadrons were located.15

On November 29, 1917, the men who remained behind at Grantham, with the blessing of the British authorities, staged a grand Thanksgiving celebration there that included not only a feast but also a football game. Shoemaker evidently returned to Grantham from Waddington to join in. Walter Chalaire, who, in addition to being a pilot in training, was a journalist, wrote a widely published article about the day, from which it appears that Shoemaker served as referee for the game: “. . . Fred Shoemaker of Nome, Alaska, whose legs are so long that he will not fit into a Maurice Farnam [sic] Shorthorn (pusher type airplane—guess they’ll have to construct a special bus for him) blew his whistle for the game to begin. . . .”16

I have found no direct documentation of Shoemaker’s time at Waddington, beyond his move from No. 47 T.S. to No. 48 T.S. on November 26, 1917,17 but the log book and letters of Oatis are extant, and it is reasonable to assume that Shoemaker’s training resembled that of Oatis. The latter did not do any flying during his first two weeks at Waddington—perhaps because he and his fellow cadets were being given yet more ground instruction, or perhaps because of poor weather or a lack of planes. Then, late in the morning of Tuesday, December 4, 1917, according to Oatis’s log book, he put in twenty-five minutes of dual flying in a DH.6 (a two-seat plane designed for training). By December 11, 1917, when Oatis wrote home, he reported that “most of us are already soloing”—having done the requisite dual time in DH.6’s, Oatis had gone up solo twice the preceding day in the same plane.

Shoemaker was also ready that day to go solo, but he “had a devil of a smash before he ever got off the ground. There was a bus laying out in the middle of that great big field with a smashed undercarriage. How Fred ever did it I don’t know, but he cut loose and tore across the field, and went smash into the wreckage. It was one of those accidents that happen occasionally and can’t be excused. His wheels had never even left the ground. He made kindling of the other bus, and tore off both his own right wings. He wasn’t even scratched.”18

Over the course of December and early January, Oatis, and presumably also Shoemaker, went up dual with instructors in R.E.8s and then also in B.E.2e’s (both were two-seater planes designed for reconnaissance and bombing) while also adding to their solo hours and practicing maneuvers in DH.6s. Oatis noted that “You have to do five hours of solo flying and make fifteen landings. Then you pass into the advanced squadron and start flying real aeroplanes…. At the finish of your elementary training you are usually selected for a certain general class of work.”19 Both he and Shoemaker were “selected,” probably by mid-January 1918, for work as observation or bomber pilots on two-seater planes.

Before the end of February Shoemaker evidently completed twenty hours of solo flying, which was apparently the main prerequisite for qualifying for a commission. The information was duly forwarded, and on March 5, 1918, Pershing cabled Washington with the recommendation that Shoemaker and a number of other members of the detachment be commissioned as first lieutenants.20 On March 29, 1918, second Oxford detachment member William Ludwig Deetjen, now also at Waddington, wrote in his diary that one of the R.F.C. officers at Waddington “had . . . Shaw, Shoemaker, and I come to his office. Our commissions had come and we were sworn in then and there.”21

By now Shoemaker and his cohort at Waddington were working towards their R.F.C. graduation certificates. In addition to receiving instruction on and practicing stunting and formation flying, they needed to add to their solo hours, make a cross-country flight, pass an altitude test, and fly an operational plane solo. Assuming his progress continued to parallel that of Oatis and Deetjen, Shoemaker probably completed these requirements in the latter part of March and then commenced training on DH.4s, the British version of the two-seater plane used for reconnaissance and bombing that he would later fly operationally.

The group of ten men who had arrived at Waddington together had by this time been diminished by two, and they would soon lose one more. About a month after Shoemaker’s unfortunate first attempt at solo flying, Sharpe was killed in a crash; Shoemaker was likely one of the men who served as a pall bearer at his funeral in Lincoln on January 11, 1918.22 Then on March 12, 1918, Middleditch and Pudrith were involved in a crash that killed the former almost instantly. Pudrith survived the accident. Deetjen noted in his diary on March 19, 1918, that he “Went down with [instructor Arthur Harold] Beach, Shuey, Oatis and Jake Stahl and ran up to the Northern Hospital to see Chick Pudrith.” Pudrith appeared to be on the road to recovery, but took a turn for the worse and died at the end of April.

Once they had finished up at Waddington, both Deetjen and Oatis went on to the No. 4 Auxiliary School of Aerial Gunnery at Marske-by-the-Sea in Yorkshire and then to the School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping at Stonehenge in Wiltshire. It seems likely, but by no means certain, that Shoemaker did the same. Unfortunately, Shoemaker’s R.A.F. service record is of little help, as whoever drew it up failed to realize that there were two American Shoemakers and entered information pertaining to Harold Goodman Shoemaker’s time at London Colney into Fred Trufant Shoemaker’s record.23

Shoemaker is next documented in early July 1918, when he was in a group of thirty-five American pilots ordered to report to the (American) Third Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun in the Loire region of central France (Oatis and Stahl were also on the list).24 Once arrived at Issoudun—where, according to another pilot, “they did not expect us and had no place to sleep”25—hopes that the group might be “mobilized as an American squadron and go to the front immediately” were dashed.26 They spent the summer, through the beginning of September, in further training, now with Americans as instructors. From the 3rd A.I.C., some of these pilots proceeded to the 2nd A.I.C. at Tours, about seventy miles northwest of Issoudun, for work at the School of Observation Training, while others, including Oatis and Stahl, were sent to the 7th A.I.C. at Clermont-Ferrand, about ninety miles southeast of Issoudun. I find no record of Shoemaker’s activities during this period, but he almost certainly spent some of the time training on DH-4s, the American version of the British DH.4.

The 11th Aero

Oatis, in an excited postscript to a letter dated September 12, 1918, wrote that “I’ve been assigned to my squadron, and am just tickled to death with everything. Have the planes I wanted, our crowd has kept together in the main.” “Our crowd” included Shoemaker and Stahl; they had been assigned to the American 11th Aero Squadron, part of the recently minted First Day Bombardment Group.

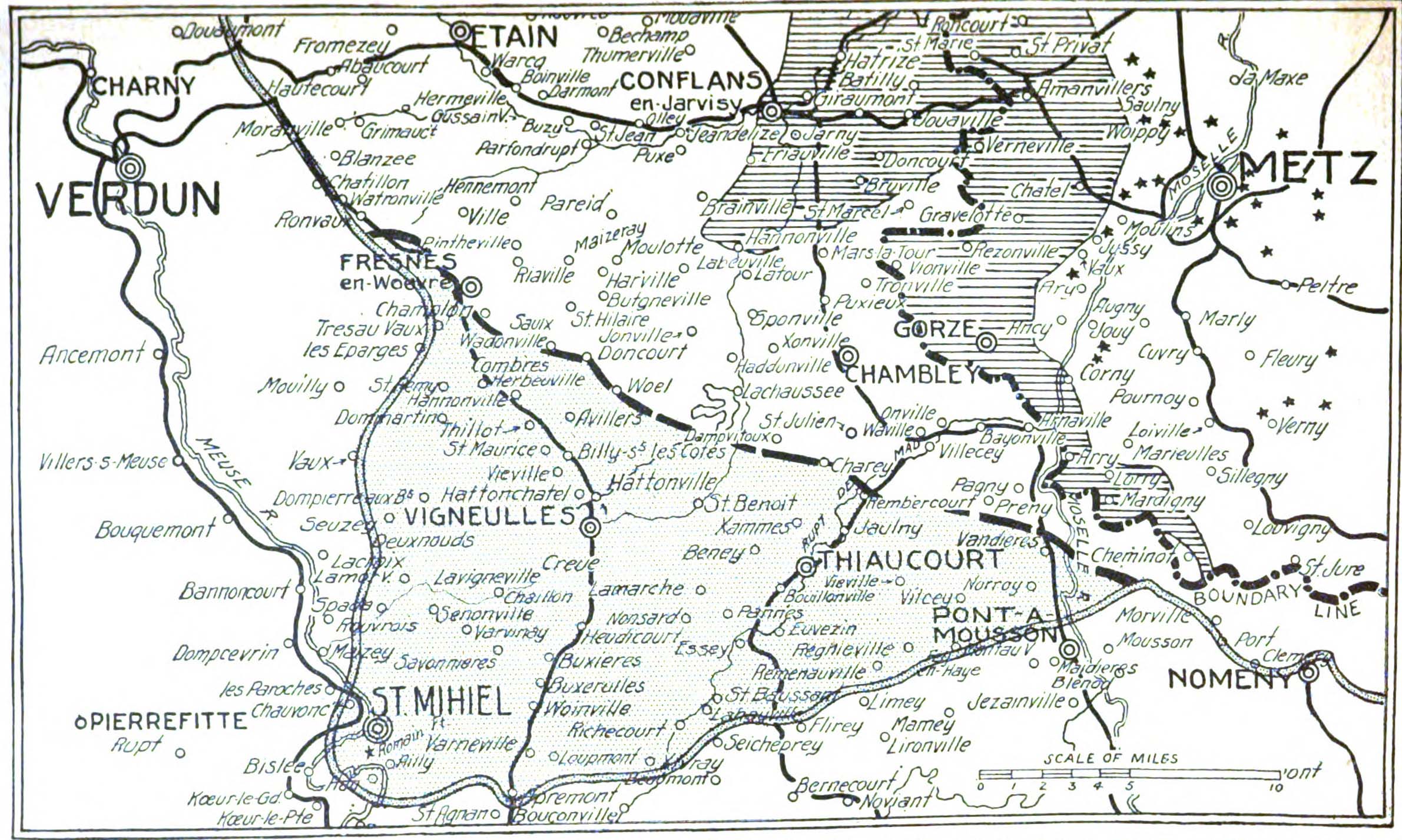

The 11th Aero was stationed at Amanty, about twenty-five miles south of St. Mihiel and the front; the field was shared with the 20th, and the 96th Aero Squadrons, the last-named being the only operational American bombing squadron up to this point. Instructions for daylight bombing had been drawn up in the course of August; on September 10, 1918, the three squadrons became the First Day Bombardment Group.27

By this time the newly-established American First Army was completing preparations for the St. Mihiel Offensive, in which the First Army, with assistance from the Allies, would seek to wipe out the German held salient that jutted southwest from the Allied line to encompass the town of St. Mihiel on the east bank of the Meuse River. It had been hoped that the attack could begin before the autumn rains, but it was delayed from the 7th until the 12th, and, in any case, the rains came early.28

On the first two days of the St. Mihiel Offensive, September 12 and 13, 1918, some of the pilots of the 11th Aero, whose planes were not yet outfitted for bombing, were tasked with observation and escort duties.29 Whether Shoemaker, like Oatis and Stahl, was among these pilots is not known.

The 11th Aero began bombing operations early on the morning of September 14, 1918, with the railway yard at Conflans-en-Jarnisy30 as the objective—but it was a near thing. John Cowperthwaite Tyler, deputy leader for the 11th Aero on this first raid, wrote in his diary that day: “Bombs just arrived at midnight and no one knew how to put them on. Still working with them and guns, when Major [James Leo Dunsworth] drives up at 7 and orders us off with or without guns and bombs. Only about half loaded, went off.”31 A flight from the 96th Aero had set out for Conflans at 6:25 a.m.; the 11th followed at 6:45, and the 20th at 7:15.32

Shoemaker was teamed up with observer Robert Newell Groner, Jr.33 The latter recalled that “10 machines left the Aerodrome at Amanty. An early start had been made and all machines were off the ground before 7:00 A.M.” Groner continues: “Before reaching the lines three machines were forced to turn back, the other seven crossing the lines at Verdun.”34 According to a post-war history of the 11th Aero: “Northwest of Verdun we turned to the east, crossed the lines just north of that historic battleground, and headed east in the race for the railroad at Conflans. The first anti-aircraft battery, affectionately known as ‘Archie,’ opened up on us before we were well over the lines.”35 Oatis’s record book indicates that they were flying at about 9,000 feet. They reached Conflans, twenty miles east of Verdun and forty-five miles northeast of Amanty, just before 8:00,36 “made good hits on tracks and storehouse,”37 and then “turned south [sic] for home.”38

Groner recounts how at this point they “were attacked by fifteen Fokkers. During the fight that ensued, one Liberty [DH-4] was crashed and shortly after one Germany [sic] plane followed.” Groner “received a bullet through the leg but continued fighting, his back towards his pilot. Their engine had stopped and [they] were going down in long spirals. [Shoemaker] had received nine bullet wounds and was unconscious. The machine was bringing itself down but [Groner] did not know this and made no move towards the controls but continued firing upwards at the diving Fokker.” Their plane “spiraled for 8,000 feet and then crashed in a forest.”39

Five planes of the 11th Aero from the original flight arrived back at Amanty. Tyler wrote in his diary that day that “[Horace Greeley] Shidler was shot down partly out of control in their lines and Shoemaker landing apparently all right in ours, neither heard from.”40 Oatis recorded in his log book “Shoemaker, Groner, Shidler, [Harold Holden] Sayre lost.”

Contrary to what Tyler understood (or hoped), both planes were brought down deep inside German territory, near Rezonville, about eight miles southeast of Conflans. And according to a German interrogation report dated September 16, 1918, both planes were completely destroyed (“vollkommen zerstört”).41 Quite remarkably, three of the four men survived. Sayre had been “erschossen” (shot dead), but there is no mention of injuries in the case of Shidler. Groner was also shot, but apparently his injury was not life threatening. Shoemaker, on the other hand, had received bullet wounds to the head, apparently mainly to the jaw, and his interrogation took place in hospital in Jouaville (approximately five miles east of Conflans); he could barely speak—perhaps poorly comprehensible speech accounts for the description of him as a “Strassenbauunternehmer” (road construction contractor).

For most of five days after being shot down, Shoemaker was unconscious. When he was once again aware of his surroundings, he found himself in a hospital in Düsseldorf where, according to the account he provided after the war, he “received excellent care. A German doctor set his broken jaw very skillfully.”42 At some point he was sent to German-occupied Liège. He later recalled that “At the time of the signing of the armistice [he] was in Liege, Belgium, with a Frenchman, Englishman and another American . . . It was at 4 o’clock they found out that peace had been declared, and the four entered a large café in Liege. At the sight of their uniforms the waiters greeted them with cries of ‘Vive La France’ and ‘huzzah.’ The Germans were dumbfounded and forgotten by the waiters who carried their trays of foods which had been ordered by the Germans to the four Allies.”43 Not long after this Shoemaker made his way to Paris where he encountered Stahl, who described him as “almost a skeleton” then, but as in time returned to good health and his normal weight.44

Groner, meanwhile, recalled being interrogated by German intelligence officers before being moved to P.O.W. camps at Karlsruhe, Landshut, and finally Villingen.45 It was presumably at Villingen that he encountered Zenos Ramsey Miller and signed Miller’s autograph book.46 Released after the armistice, Groner went initially to Switzerland and then to France. He was fortunate to be able to return to the U.S. soon thereafter, boarding the S.S. Adriatic at Brest and arriving in New York on January 31, 1919.47

Shoemaker sailed from Brest on the U.S.S. Georgia on March 19, 1919, and arrived at Newport News on April, 1919.48 He settled once again in Mt. Clemens, joining in the family golf course business and working in insurance and real estate.49

mrsmcq June 4, 2024

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Shoemaker’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Fred T Shoemaker. On his place and date of death, see “Fred Shoemaker, Famous War Flier, Passes Away.” The photo is from Joseph Kirkbride Milnor’s photo album.

2 Barker, Early Families of Herkimer County New York, pp. viii and 225 ff.

3 The forename(s) is/are variously given, e.g., Hanyoost, John Joseph, etc. On him see Vrooman, Forts and Firesides of the Mohawk Country New York, p. 257. See Daughters of the American Revolution, Lineage Book, entries for Charlotte Shoemaker Rottman (vol. 33, 1900) and Kate Trufant Shoemaker Johnson (vol. 38, 1901).

4 Schenck, History of Ionia and Montcalm Counties Michigan, pp. 457–48.

5 On the Schumachers see also documents available at Ancestry.com.

6 Secretary of the Commonwealth, Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, vol. 16 (1907), p. 82; Chamberlain, History of Weymouth Massachusetts, vol. 4, pp. 697–700; Howe, Genealogy of the Bigelow family of America, p. 143; Leeson, History of Macomb County, Michigan, pp. 605–06.

7 See item overview for “Mount Clemens Junior A.C. semi-pro football team, Mount Clemens, Michigan”; and see “Fred Shoemaker, Famous War Flier, Passes Away.”

8 “Fred Shoemaker, Famous War Flier, Passes Away.”

9 “Mt. Clemens.”

10 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

11 Oatis, letter of July 17 [1917].

12 Oatis, letter of August 22, 1917.

13 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

14 See, for example, History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 151.

15 Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917.

16 Chalaire, “Thanksgiving Day with the Aviators Abroad.”

17 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Fred T. Shoemaker.

18 Oatis, letter of December 11, 1917.

19 Ibid.

20 Cablegram 678-S.

21 Deetjen, diary entry for March 29, 1918.

22 See Oatis’s letter of January 14, 1918.

23 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Fred T. Shoemaker.

24 Coulter, “Special Orders No. 105″; see also Dwyer, “Memorandum No. 8 for Flying Officers.”

25 Goettler, diary entry for July 10, 1918.

26 Oatis, letter of July 12, 1918.

27 “First Day Bombardment Group,” p. 4.

28 Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3, p. 120 (editorial comment).

29 See Thomas, The First Team, pp. 67–68, regarding the work of the 11th (and 20th) Aero on September 11 and 12, 1918.

30 Rennless, Independent Force, p. 10, notes that Germany had an adequate supply of munitions, but that “if the rolling stock which delivered the munitions was destroyed, it could not be supplied. Goods yards and shunting stations were therefore prime targets, as well as converging railway lines where large destruction of track could create bottlenecks of both men and materials.”

31 Tyler, Selections from the Letters and Diary of John Cowperthwaite Tyler, p. 127

32 Rath and Harrington, First to Bomb, Rath’s diary entry for September 14, 1918. Here and elsewhere accounts differ; I assume Tyler’s “at 7″ was an approximate time.

33 Under pressure of battle, record keeping clearly suffered. Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 94, lists seven teams from the 11th on this mission, but Shoemaker and Groner are not among them; it is possible that the bottom portion of Rath’s list was cut off.

34 See Groner’s account on p. 133–34 of Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany.

35 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 149.

36 The time is extrapolated from Clair B. Laird’s raid report on p. 61 of “11th Squadron.”

37 Tyler, Selections from the Letters and Diary of John Cowperthwaite Tyler, p. 127.

38 Groner’s account, cited above.

39 Ibid. Laird’s report, cited above, gives the number of enemy planes as 7–9; Tyler, cited above, recalled “ten or eleven.”

40 Tyler, Selections from the Letters and Diary of John Cowperthwaite Tyler, p. 127.

41 Kraft, [Documents submitted to the American Consul in Stuttgart in June 1927 regarding American aviators killed or captured in 1918.], pp. [33–34]. Kraft indicates the plane’s serial number was 32152; see Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File, p. 97 on this plane. Georg von Hantelmann of Jasta 15 claimed a DH-4 north of Gorz (Gorze) at 8:00 a.m. (Allied time), and this can reasonably be assumed to have been Shoemaker and Groner’s plane. See the relevant entry in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II.

42 Shoemaker’s account is on p. 273 of Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany.

43 “Veteran Gives Talk on Armistice Day.”

44 “When Hell Broke Loose, Stahl was Busy ‘Over There’,” p. 10.

45 See Groner’s account, cited above.

46 Miller, Autograph Book [unpaginated].

47 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Robert N Groner Jr.

48 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Fred T Shoemaker.

49 See census records available at Ancestry.com, and “Fred Shoemaker, Famous War Flier, Passes Away.”