(Kearny, New Jersey, April 28, 1896 – Upper Arlington, Ohio, October 27, 1989).1

Oxford & Grantham ✯ Training at No. 76 H.D.; Waddington ✯ Marske, Stonehenge, C.D.P. ✯ France & the 166th Aero ✯ The 11th Aero & home

Foss was the oldest of three sons; his father died when he was about sixteen, and the middle brother four years later.2 Foss attended New York University, a member of the class of 1918. Presumably accommodations were made for studies interrupted by the war; Foss’s senior thesis, “Relations Between Germany and Russia 1904 to 1910,” is dated May 1919.3 His draft registration card makes no mention of his studies, but indicates that in June 1917 he was working as an insurance agent. Soon after registering, he enlisted in the Signal Enlisted Reserve Corps at the Essington Flying School near Philadelphia.4 He then went to Ohio State University for ground school, graduating September 1, 1917.5

Along with most of the rest of his O.S.U. classmates, Foss was selected for training in Italy. The twenty-three men received orders the morning of Thursday, September 6, 1917, to report to Mineola on Long Island and boarded a train heading east that day, arriving the next morning. After a medical inspection, they were given the weekend off. Foss went home to Jersey City, taking with him his classmate, Murton Llewellyn Campbell, who, as a midwesterner, was otherwise at loose ends. The men spent the following week getting kitted out and waiting for embarkation orders.6

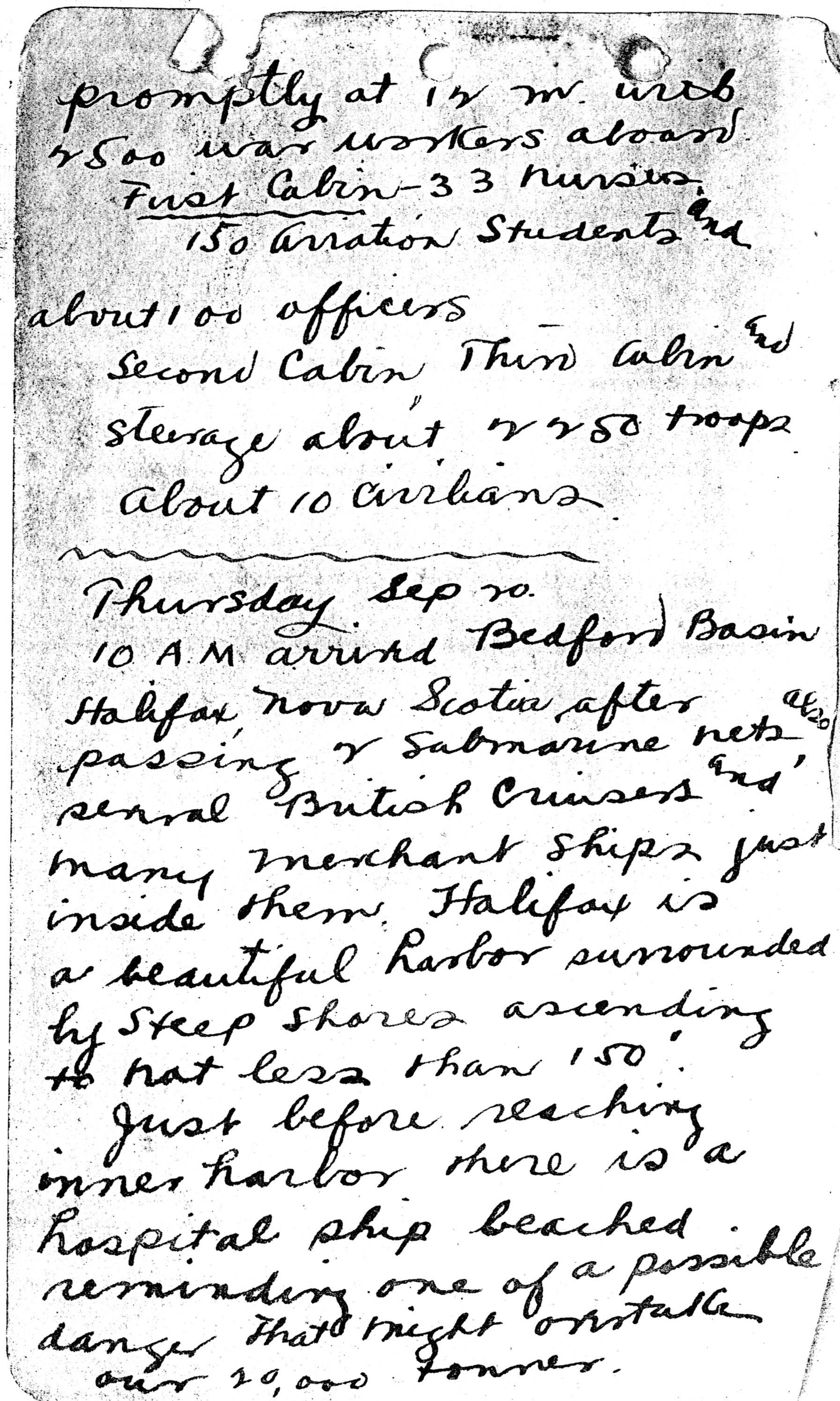

Finally, on September 18, 1917, Foss, along with the other cadets of the 150 man “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment,” set sail from New York on the Carmania. After a stop at Halifax, they set out on September 21, 1917, as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing. Foss was clearly a personable young man, and he made friends on shipboard, including some in a contingent of nurses destined for Northwestern’s Base Hospital 12, as well as other civilian and military passengers.7

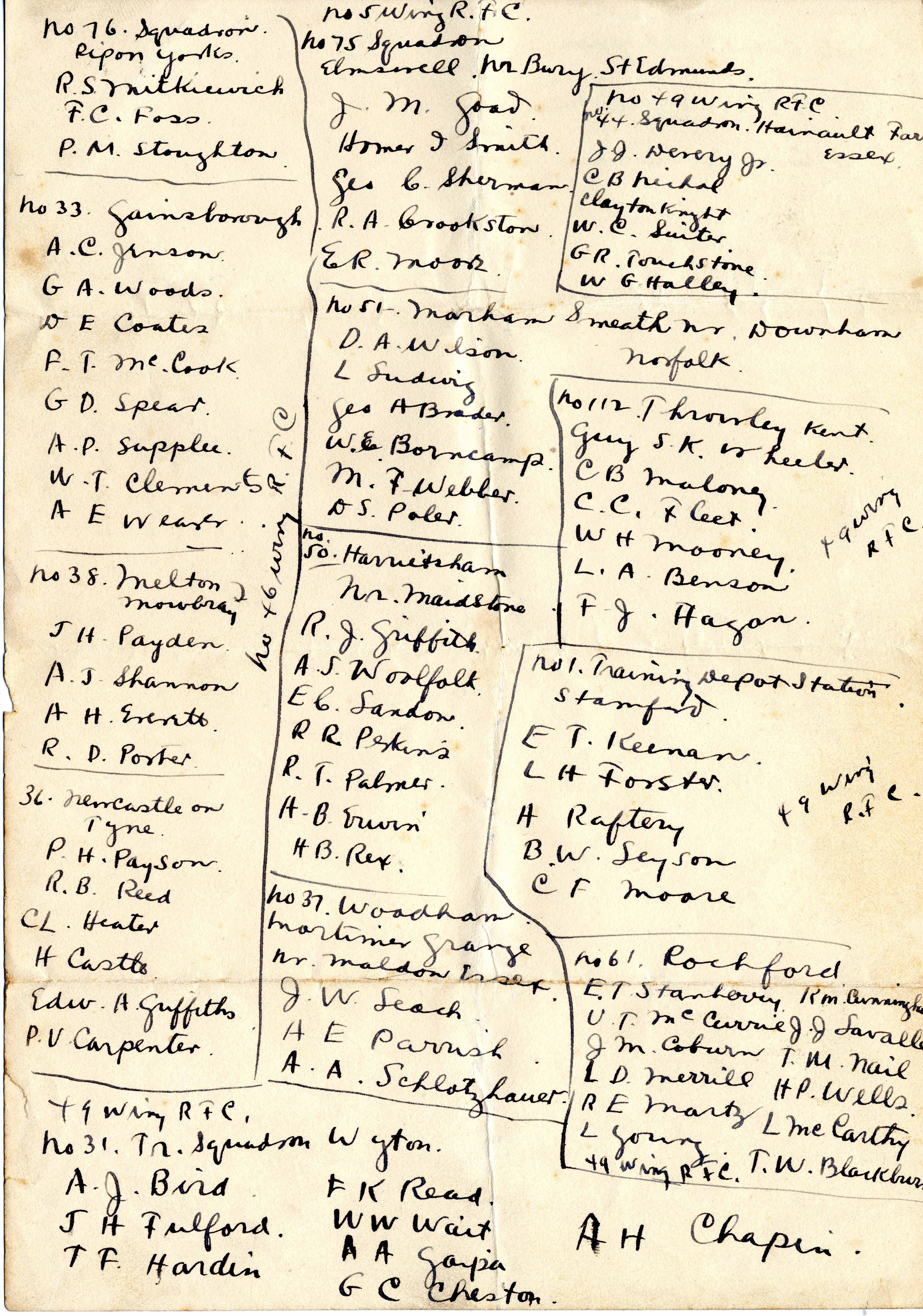

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the cadets were ordered not to Italy, but to Oxford, where they repeated ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. Foss, along with about sixty of the cadets, was housed at The Queen’s College, with fellow detachment member William Ludwig Deetjen in charge. Foss became close friends with Perley Melbourne Stoughton, a graduate of M.I.T.’s ground school. The two of them visited the R.F.C. aerodrome at Port Meadow in northwest Oxford and very nearly got their first “flip” there, but bad weather intervened. While out walking in Oxford, Foss and his ground school classmate Albert Sidney Woolfolk met Lady Osler, wife of Sir William, and were invited to tea.

On November 3, 1917, Foss and about 130 of his fellow second Oxford detachment members boarded the train for Grantham in Lincolnshire where they attended machine gun school at Harrowby Camp. Again with Stoughton, Foss made a bee-line for the air field at nearby Spittlegate. There he had a twenty-minute flight with a Captain Spence–and witnessed a fatal crash.8

Training at No. 76 H.D.; Waddington

The day after Thanksgiving, Foss received word that he, Stoughton, and Raphael Sergius De Mitkiewicz were to go on Monday, December 3, 1917, to No. 76 Home Defense Squadron, whose headquarters was in Ripon in Yorkshire. Two days later (December 5, 1917), Foss went from Ripon to Helperby, where there was a detachment from 76; here he was taken up for a “good time flip with [John Overton Cone] Orton.”9 On December 11, 1917, Foss was transferred to yet another 76 location, Copmanthorpe, where he enjoyed getting to know Australian architect-turned-aviator Thomas Roy Irons, as well as poet-turned-aviator Arthur Lewis Jenkins, whose death in a crash landing on New Year’s Eve saddened Foss greatly.

The planes flown by No. 76 Squadron at this time were the single-seat B.E.12a, the two-seat R.E.8, and the two-seat B.E.2e—the last obsolete and used mainly for training.10 Foss went up for the first time as a pupil the day after his arrival at Copmanthorpe with instructor Gerard James Wilde in a B.E.2e. On his fourth training flight, on December 21, 1917, Foss, again with instructor Wilde, made his first attempts at taking off and landing; by January 11, 1918, he had gotten in six and a half hours dual flying, all on B.E.2e’s.11 Soon after this he began ten tedious days in quarantine with an otherwise unidentified man named Parkinson; both had come into contact with suspected scarlet fever.

On January 26, 1918, Foss received orders to proceed to Waddington, where he rejoined Stoughton and De Mitkiewicz (who had apparently remained at Helperby when Foss went to Copmanthorpe). Two days later Foss wrote in his diary “We are to go overseas with R.F.C. on DH-9s—bombing”—understandings and predictions like this were often wildly inaccurate, but it was, in fact, the case that the men assigned to Waddington were being trained to fly DH.9s and DH.4s, both used for bombing.

On the evidence of his diary, Foss got in no flying during the first two weeks of February. More than once he notes in his diary “Heavy wind, plenty of crashes,” so some flying was taking place, but perhaps not for beginning students. However, soon after he, Stoughton, and De Mitkiewicz were reassigned to No. 47 T.S. (also at Waddington) on February 14, 1918, Foss started piling on the hours in DH.6s (a two-seater aircraft used for training), going solo for the first time on February 17, 1918, and also stalling and crashing for the first time. This mishap, fortunately not serious, must have been particularly unnerving, as it was during this period that a number of Oxford cadets were killed in training accidents. Foss recorded the names of these men in his diary.

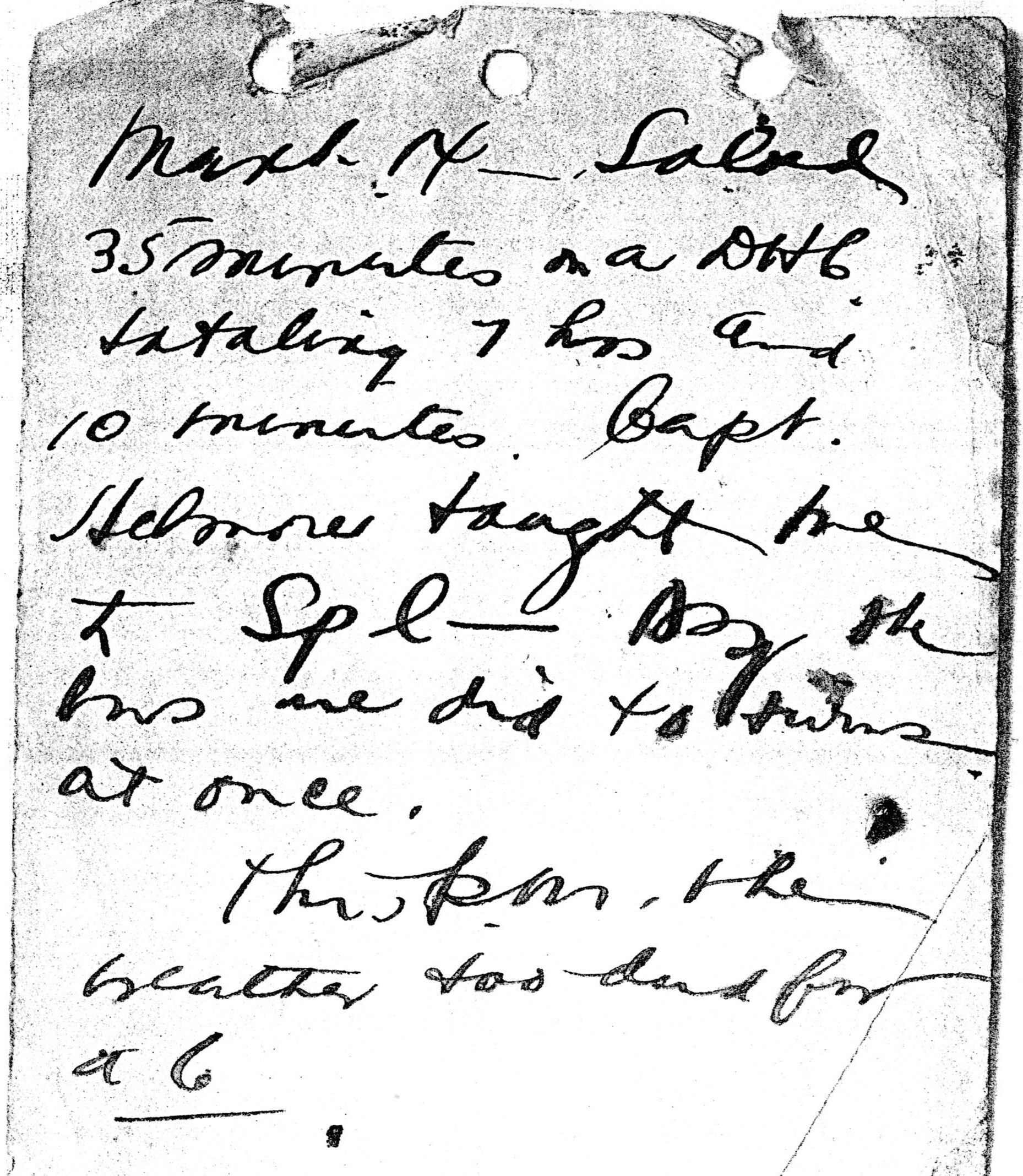

In early March 1917 Foss and Stoughton were able to take a break and go to London for some shows and relaxation. A week later Foss was back at Waddington learning “ to Spl—ass the bus” (make a tight turn), and he soon started training on an Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8 and, in early April, an R.E.8; these were both operational (as opposed to training) two-seaters.

According to his pilot’s log book, Foss did not fly at all from April 9 through April 18, 1918, and was perhaps on leave.12 His fellow second Oxford detachment member Joseph Raymond Payden kept a photo of him captioned “Foss in Scotland” that may have been taken around this time.13

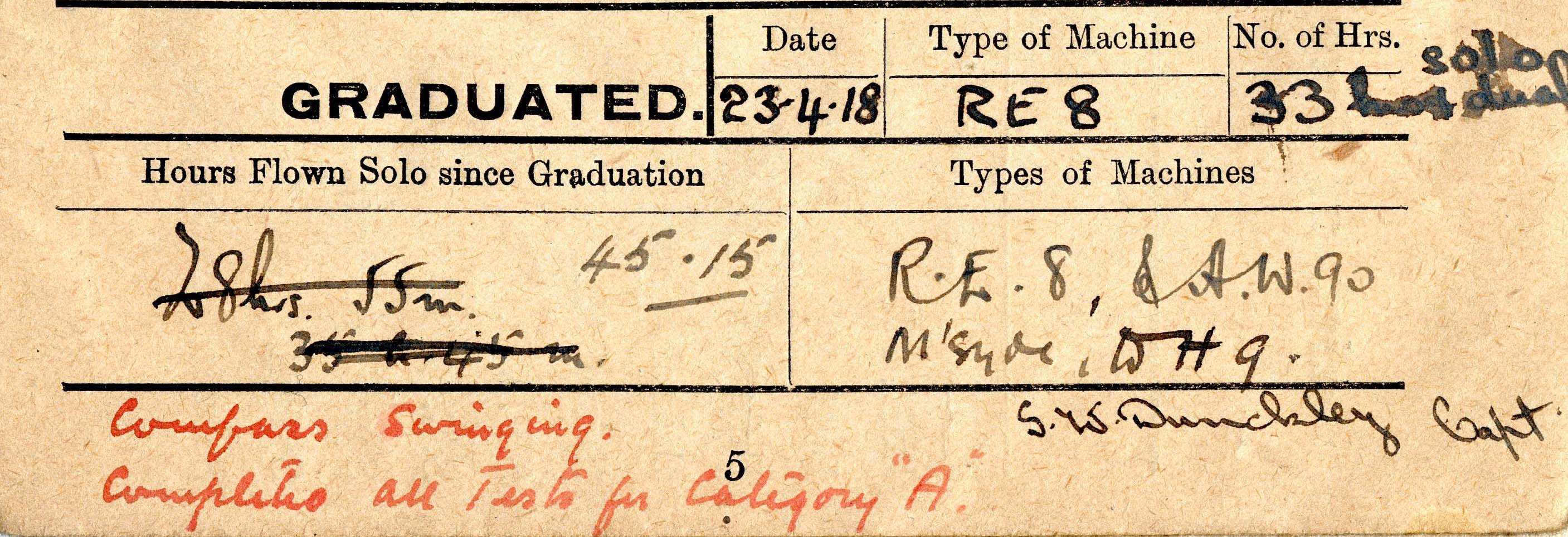

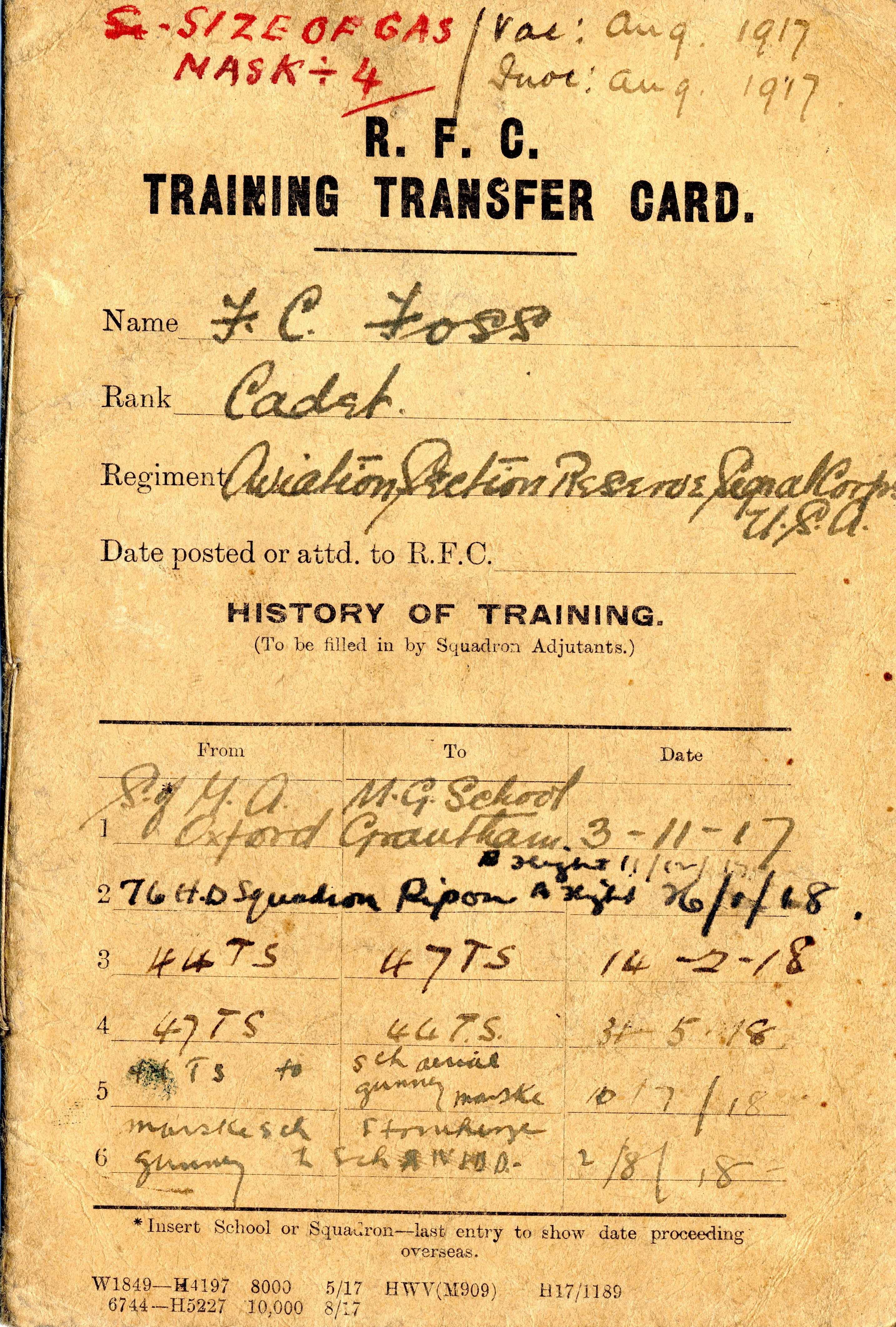

Foss resumed flying on April 19, 1918, and on April 23, 1918, for the first time, flew solo in an operational (as opposed to instructional) plane, an R.E.8, thus passing one of the major tests required for graduation from the first stage of training. And, indeed—despite his not passing the height test, the requirement to fly at an altitude of 8,000 feet, until April 27, 1918—Foss’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card records his having graduated on April 23, 1918.

Pershing, meanhile, had sent a cablegram dated April 8, 1918, to Washington recommending that Foss, along with thirty-eight other second Oxford detachment members, as well as many other cadets, be commissioned.14 Pershing asked that they be made “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying.” The “non-flying” status arose from an effort by Pershing to rectify an injustice. In an earlier cable to Washington dated March 13, 1918, Pershing had described the situation of the approximately 1400 aviation cadets in Europe, some of whom had waited three months to start flying training, and some of whom, after five months, were still waiting and might have to wait another four.15 “All of those cadets would have been commissioned prior to this date if training facilities could have been provided. These conditions have produced profound discouragement among cadets.” To remedy this injustice, and to put the European cadets on an equal footing with their counterparts in the U.S., Pershing asked permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .” Washington approved Pershing’s plan in a cable dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.”16

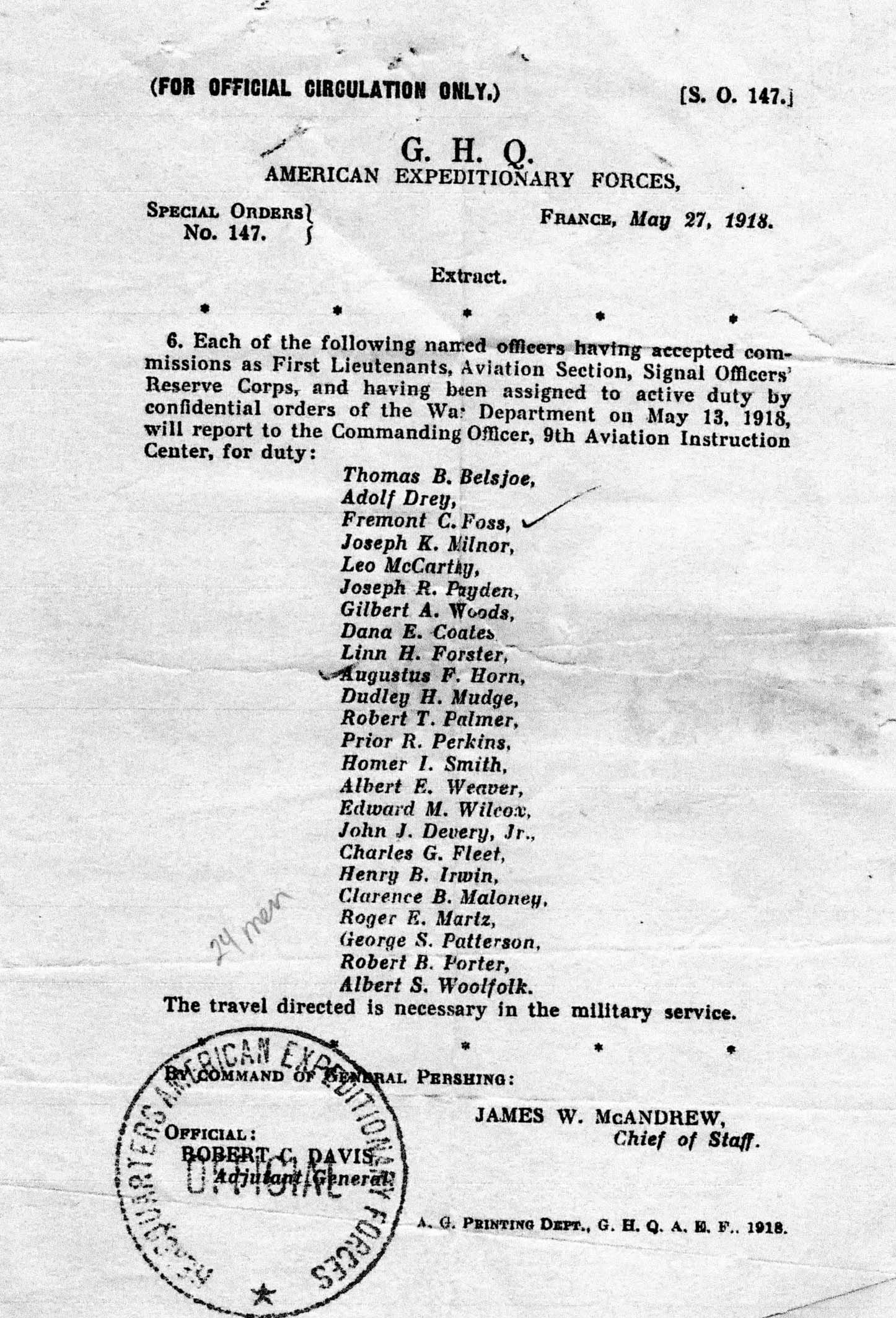

Washington took its time responding to Pershing’s April 8, 1918, cable. On April 30, 1918, an impatient Pershing wrote: “Request action taken on . . .” and lists cables dated March 29 through April 8, 1918.17 The cable from Washington confirming, finally, the commissions requested April 8, 1918, is dated May 13, 1918.18 For Foss and most of the other second Oxford detachment members listed in the April 8, 1918, cablegram, the “non-flying” status was irrelevant, as they had completed enough flying and training to qualify for their commissions by the time word of the May 13, 1918, cablegram from Washington trickled down. Foss kept a copy of an extract from Special Orders 147 dated May 27, 1918, that recorded that he and a number of others had been commissioned and placed on active duty by the May 13, 1918, cablegram.19

On the last day of May Foss was assigned to No. 44 Training Squadron, which was also at Waddington. Having put in just over sixty-three hours on DH.6s, AW F.K.8s and R.E.8s, he now commenced training on DH.9s, a two-seater bomber used also for reconnaissance. For the first four days of June he flew dual with his instructor, but then almost exclusively solo, practicing turns, formation flying, bombing, and aerial fighting with his fellow second detachment member, Walter Andrew (“Jake”) Stahl. By June 20, 1918, when he last flew at 44, Foss had accumulated eighty-two hours of flying.

It was apparently during the last days of June that Foss made a tour of cities in England and also visited Wrexham in Wales, where he had friends. His travelling companion was his fellow second Oxford detachment member Joseph Raymond Payden, who provided an account of their trip in a letter home.20

In the first part of June 1918 Foss was assigned to No. 2 Fighting School at Marske in the northeast of Yorkshire.21 There is no record of his flying during his first two weeks at Marske, and the time was presumably taken up with class work. Then, in the last week of July, Foss put in nearly eight hours solo on DH.9s and DH.4s, doing some formation flying, but mainly doing firing and fighting practice. On his last day flying at Marske (July 31, 1918), he flew forty minutes in a DH.9a (a DH.9 with a Liberty engine).

From Marske, on August 2, 1918, Foss and fellow second Oxford detachment member Gilbert Allan Woods went to the No. 1 School of Aerial Navigation and Bomb Dropping at Stonehenge. Foss began flying again the next day. His initial flight was on another DH.9, but then he spent two weeks piloting B.E.2e’s and B.E.2c’s, practicing cloud penetration, formation flying, and bombing; he moved back to DH.9s, DH.9a’s, and DH.4s in mid-month. At the end of the month, having racked up by now close to one hundred hours of solo flying, Foss, again along with Woods, left Stonehenge to report to London; he was initially assigned to the Central Despatch Pool of the R.A.F. as a ferry pilot.22

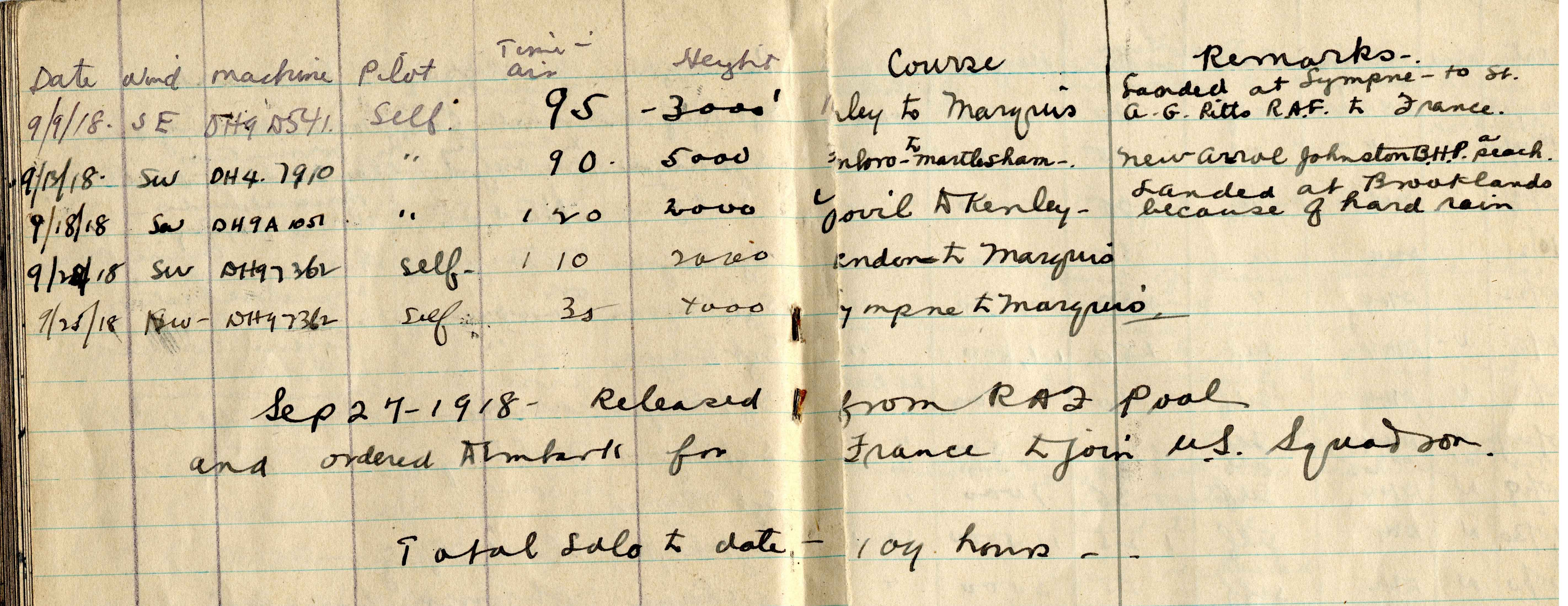

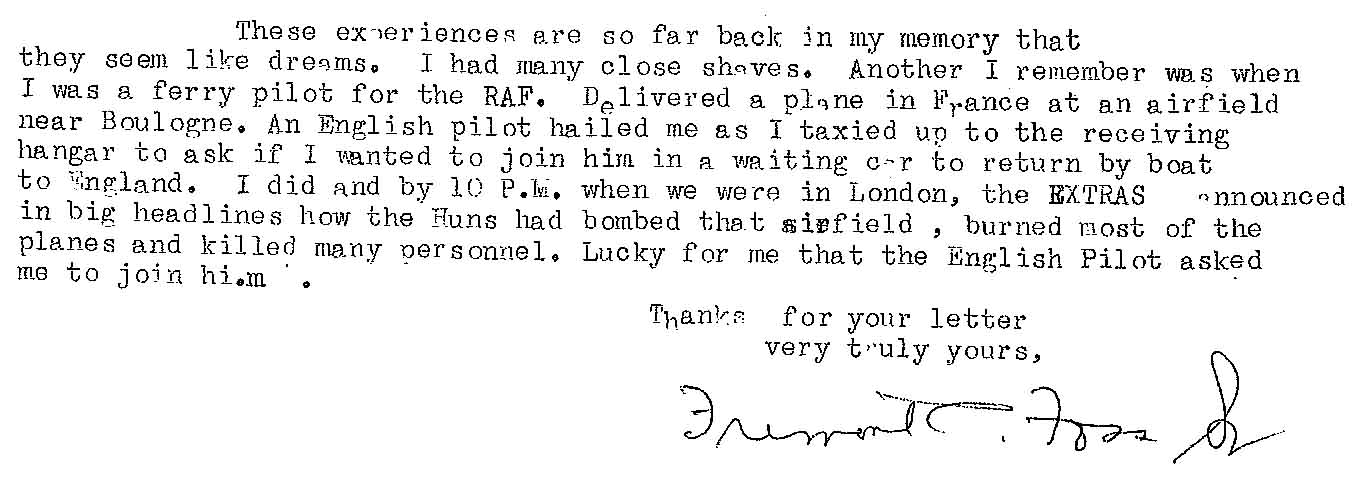

On September 9, 1918, Foss landed for the first time in France, having ferried DH.9 D541 to Marquise. He next flew a DH.9 to Marquise on September 23, 1918.23 Many years later he recalled this as a “close shave.” “An English pilot hailed me as I taxied up to the receiving hangar to ask if I wanted to join him in a waiting car to return by boat to England. I did and by 10 P.M., when we were in London, the EXTRAS announced . . . how the Huns had bombed that airfield. . . .”24 Thirteen German planes had bombed the depot at Marquise during the night of September 23-24, 1918, in the most destructive raid on a British aviation facility of the war.25

According to a note in his log book dated September 27, 1918, Foss was “released from RAF pool and ordered to embark for France to join U.S. Squadron.” Initially assigned to the 1101 Aero Replacement Squadron at Colombey-les-Belles, he was ordered on October 7, 1918, to report to the American 1st Day Bombardment Group at Maulan. There, on October 9, 1918, he was assigned to U.S. No. 166 Aero Squadron, joining fellow second Oxford detachment members Paul Vincent Carpenter, John Joseph Devery, Harrison Barbour Irwin, Stoughton, and Albert Elston Weaver, who had been there since the latter part of September, and Linn Daicy Merrill and Phillips Merrill Payson, who had reported on October 4, 1918.26

On September 25, 1917, two weeks before Foss’s arrival, the 166th had moved from Colombey-les-Belles to Maulan aerodrome and joined the 1st Day Bombardment Group; they were flying “Liberty DH-4s,” i.e., DH.4s with American Liberty engines. Nine days after Foss’s arrival, on October 18, 1918, the squadron made its first sortie.27 After this, weather conditions precluded missions until October 23, 1918, and the 166th’s second mission was Foss’s first. His observer/gunner was Guerin Todd, another New Jersey native, who had joined the squadron two days after him. Their experience was not unlike that of Carpenter and his observer Steele on this same mission.

At 2:15 p.m. on the 23rd, a formation of thirteen planes from the 166th took off, with the Bois de Barricourt, fifty miles north of Maulan, as their objective; they were joined by formations from the 96th, 20th, and 11th Aero Squadrons. Flying at about 10,000 feet, only seven of the thirteen “teams” from the 166th reached the objective and were able to drop their bombs. Near the Bois de Barricourt they encountered a number of Fokkers. Many years later, Foss recalled the mission. He credited Todd, a mechanical engineer, with having rigged their plane (33018) with Lewis machine guns

on the floor aimed out at any enemy who approached from below and behind. . . . A number of our planes had turned back before we went over the lines because of various faults. We went over in a 5 formation, were attacked, the floor gun went into action, the engine radiator was hit, Lt. Todd was wounded and eventually we landed with a dead engine behind our lines at a field remount station and turned over on account of the terrain. Todd was thrown out bleeding from wounds in his arms and legs. Fortunately I was not hit.28

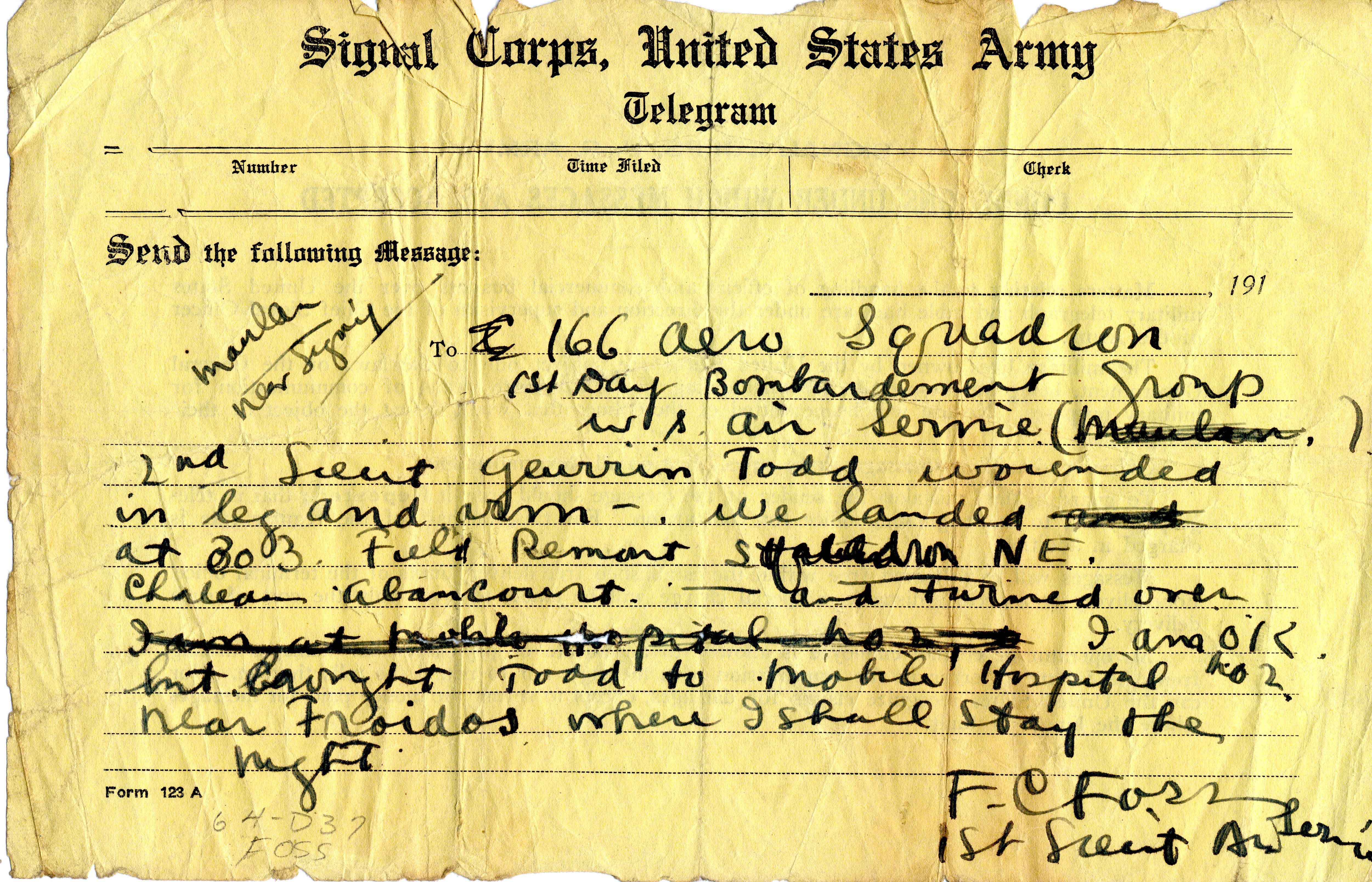

In his log book Foss recorded that Todd was “wounded 5 times in left leg & right arm.” He sent a telegram back to the 166th: “2nd Lieut Guerin Todd wounded in leg and arm. We landed at 303 [? number unclear] Field Remount Squadron N.E. Chateau Abancourt and turned over. I am OK but brought Todd to Mobile Hospital No. 2 near Froidos where I shall stay the night.”29 They had come down near the largely destroyed Chateau d’Abancourt, about sixteen miles due east of Verdun. There is no information about how Foss made the journey back south to his squadron at Maulan.

The 166th flew ten more missions (sometimes two in a single day), and Foss participated in all of them. In many instances, he and his observer “did not reach objective.” On his second mission, on October 27, 1918, his log book notes “engine nearly cut out and I landed on gravity”; on his third: “Same thing happened again.”30 Having been the last pilot to join the squadron, he probably was stuck with planes the other pilots did not want. On his fourth mission, in the afternoon of October 29, 1917, a bombing raid on Damvillers, Foss, with Ellis Corey Balsinger as his observer/gunner, once again had to make a forced landing, again, fortunately, in allied territory and this time with no injuries. The next day, with observer/gunner Harry Dawson Hotaling, he flew two missions. On the first one, he apparently reached the objective, Belleville, where 1,000 kilos of bombs were dropped by the formation; on the second his log book indicates that the engine overheated. He flew one mission with Harry Alexander Schary as his gunner/observer, and the final two or three with Hyman H. Lurie.”31 Regarding his mission with Lurie on November 4, 1918, Foss’s log book notes read “raided Montmedy; attacked by 16 Huns and lots of archie.” Foss and Lurie took part in the squadron’s final mission the morning of November 5, 1918.

Not long after the armistice, Foss was reassigned to the 11th Aero Squadron, commanded by his fellow second Oxford detachment member Charles Louis Heater; he then reported to the Second Aviation Instruction Center at Tours to await orders home. He sailed from Brest on February 2, 1919, on the La France, arriving in record time at New York on February 9, 1919.32 He was honorably discharged on February 18, 1919.33 According to a newspaper account from around this time, Todd, the observer wounded October 23, 1918, had been left “crippled and he is forced to use two canes.”34 Nevertheless, Todd went on to have a successful career as a manufacturing executive and, in his letter to Calow from about 1966, Foss noted that Todd “was O.K. the last time I saw him at least 15 years ago.”35

Foss settled initially in Detroit, but then was for a time in New Orleans, where he married.36 Foss and his wife travelled together to Europe in 1923; they had two children before she died in 1926.37 He returned to New Jersey where he lived with his (remarried) mother, stepfather, and brother, Spencer.38 He spent his last years in Ohio, where his daughter had settled. His granddaughters remember him with great affection.

mrsmcq July 10, 2017; revised November 5, 2021

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Foss’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Fremont Cutler Foss. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com and Ohio Department of Health, Ohio, Deaths, 1908-1932, 1938-2007, record for Fremont C Foss. The photo is a detail from a group photo of Squadron 8 at the Ohio State University School of Military Aeronautics.

2 See Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Fremont Fass [sic]; on the death of his father, Freeman J. Foss, see “Foss”; on his brother, see “Foss, Howard L.”

3 On his N.Y.U. attendance, see Lydecker and Wickwire, Pocket Directory of the Zeta Psi Fraternity of North America 1922, p. 26; on his thesis, see Walker, “University College Senior Theses.”

4 See the brief military biography included in the memo from Foss dated March 7, 1919, regarding discharged soldiers’ bonus, among Foss, Papers.

5 See “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

6 Information about this period is taken from Murton Campbell, diary entries for September 6–18, 1917.

7 Much of the detail in this and subsequent paragraphs regarding Foss’s activities through March 1918 are taken from his diary.

8 The ride with the otherwise unidentified Captain Spence and the fatal crash are recorded in Foss’s diary entry for November 4, 1917. The pilot killed was apparently Frank Lockwood, a second lieutenant in No. 15 T.S. who was flying RE8 A3693; see “Lockwood, F. (Frank).”

9 Foss, diary entry for December 7, 1917.

10 See Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 417.

11 R.F.C. Training Transfer Card.

12 Foss’s log book is one of the items in Foss, Papers. Details of planes and hours flown during training and operationally in what follows are taken from the log book.

13 Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915-1925, p. 34.

14 Cablegram 874-S.

15 Cablegram 726-S.

16 Cablegram 955-R.

17 Cablegram 874-S.

18 Cablegram 1303-R..

19 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 147.”

20 Payden’s letter is reproduced in “Payden Has Seen Much of England.” I have not been able to identify Foss’s Welsh friends.

21 Foss’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card indicates he went to Marske on July 10, 1918; Biddle, “Special Orders No. 116,” is dated July 12, 1918; Edward Milton Wilcox recalled the date as July 5, 1918 (Ancestry.com, Connecticut, U.S., Military Questionnaires, 1919-1920, record for Edward Milton Wilcox. On the changing number, naming, and remit of the school at Marske, see Jefford, Observers and Navigators, p. 51. When Foss was there, it was officially “No. 2 Fighting School,” but his log book is signed by a Captain Turner who designates it “No. 2 Sch. Aerial Fighting.”

22 This is recorded in the brief military biography in the memo from Foss dated March 7, 1919, regarding discharged soldiers’ bonus, among Foss, Papers.

23 The date in Foss’s log book is difficult to read. He recorded the plane as “DH9 7362″; probably in error, he recorded this same plane as flown to Marquise September 25, 1918.

24 Foss, letter to Richard Calow. This suggests his arrival the same day, i.e., September 23, 1918, but it must have been September 24, 1918.

25 On German bombing of British aerodromes, see Jones, The War in the Air, p. 161.

26 Copies of orders preserved in Foss’s papers provide details of his assignments. See Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron,” p. 87, for a roster of officers of the 166th.

27 Information on the 166th and Foss’s activities while with the squadron is taken from Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron” and the appended documents, and from Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations.”

28 Foss, letter to Richard Calow.

29 A draft of the telegram is included in Foss, papers. Foss used his army issued flight suit to keep Todd warm during the ride to Froidos; this and the muffler in the pocket went missing while Foss was caring for his wounded observer. The paper trail left by the army’s trying to account for these items stretched into 1920 (Foss, Papers).

30 According to Foss’s log book, his third mission took place on October 28, 1918. The record of missions flown in Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” indicates that there were no missions flown on that day, but that Foss and observer Balsinger were among those who “did not reach the objective” on the first of two missions on October 29, 1918.

31 Rath (see preceding note) lists two missions for November 3, 1918, and lists Foss as having participated in both of them; the second one, which, according to Rath, Foss flew with Lurie as his observer, does not appear in Foss’s log book.

32 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for officers on S. S. La France, where he is listed as “Fremont C.”

33 Information on Foss’s post-Armistice assignments and activities are taken from copies of orders preserved in Foss, papers, and from the memo Foss wrote on March 7, 1919, regarding discharged soldiers’ bonus.

34 This is from a newspaper article titled “Aviator Foss Back” that is preserved in Foss, papers; it was apparently clipped from The Jersey Journal of February 25, 1919.

35 See Ancestry.com, 1930 United States Federal Census, record for Guerin Todd.

36 See Ancestry.com, 1920 United States Federal Census, record for Fremont Cutler Foss; and Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925, record for Fremont Cutler Foss.

37 See Ancestry.com, U.S., Atlantic Ports Passenger Lists, 1820-1873 and 1893-1959, record for Fremont C Foss; Ancestry.com, New Orleans, Louisiana, Death Records Index, 1804-1949, record for Bethea Bush Foss; and “Fremont C. Foss, Jr.”

38 See Ancestry.com, 1930 United States Federal Census, record for Fremont C Foss; Ancestry.com, 1940 United States Federal Census, record for Fremont C Foss.