(Walpole, Massachusetts, November 18, 1895 – Riverside, California, February 3, 1975).1

Oxford and Grantham ✯ Scampton ✯ Waddington, Bircham-Newton, C.D.P. ✯ France and the 11th Aero ✯

George Dana Spear’s family had deep roots in New England on both his father’s side and his mother’s. The Spears trace their ancestry back to a George Spear who was born in England around 1613 and who is documented in Massachusetts in 1644.2 This George Spear died in what is now Maine, and some of his descendants, George Dana Spear’s ancestors, lived now in Norfolk County in Massachusetts, now in various towns in Maine. Eventually Israel Spear II, George Dana Spear’s great-grandfather, born in Maine, married a woman from Sharon, Massachusetts, and by 1850 he had settled the family in nearby Walpole, Massachusetts.3

George Dana Spear’s mother, Julia Smith Fuller, was a descendant of the Dr. Samuel Fuller who came to America on the Mayflower.4 She married Frank Newell Spear in 1895, and George Dana was the first of the couple’s three children.5 Evidently a promising student, George Dana Spear was awarded scholarships to study at M.I.T.6 He majored in electrical engineering and was in the class of 1917.7 When he registered for the draft in June of that year, he indicated that he was working for the Edison Electric Illuminating Company in Boston; he had also served for a year in the reserve infantry, perhaps in the Massachusetts National Guard.8

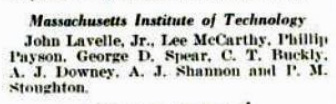

Spear was accepted into the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps on July 2, 1917, and he attended ground school at M.I.T.9 His small class of eight men graduated on September 1, 1917.10 Of those eight, six—John Lavalle, Leo McCarthy, Phillips Merrill Payson, Andrew Joseph Shannon, Spear, and Perley Melbourne Stoughton—chose or were chosen to train in Italy, and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian detachment” who set sail from New York for Europe on the Carmania on September 18, 1917.

After an initial call at Halifax, the ship joined a convoy and set out on September 21, 1917, for the Atlantic crossing. The men travelled first class. They had few obligations other than attending Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, and, once the convoy entered dangerous waters, taking turns at submarine watch. The Carmania arrived at Liverpool on October 2, 1917; the expectation was that the men would cross the Channel and proceed to Italy.

On disembarking the men were informed that plans had changed and that they would remain in England. They boarded a train for Oxford, where they were to go through ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. Another, smaller, group of American cadets that had arrived a month earlier came to be called the “first Oxford detachment”; the “Italian detachment” became the “second Oxford detachment.”

At Oxford the men were divided into two large groups. Ninety were assigned to Christ Church College under Elliott White Springs and the remaining sixty, including apparently Spear, to The Queen’s College in the charge of William Ludwig Deetjen, whom Spear probably knew from ground school at M.I.T. as well as from their Atlantic voyage.11

Initially disappointed, to put it mildly, by the change from Italy to England, the men before long became reconciled to it. Their British instructors, unlike the ones in the U.S., had had war flying experience, and this added considerable interest to the course work. Since the men had already covered much of the material, they did not have to study especially hard, and they enjoyed Oxford hospitality and spent leisure time exploring the town and surrounding countryside.

It appears from entries in the diary of second Oxford detachment member Fremont Cutler Foss that Spear roomed with, or perhaps on the same landing with, Foss, Frank Aloysius Dixon, McCarthy, and Stoughton at Queen’s, and that the five men remained together when all the detachment members were reassigned to Exeter College in the aftermath of some bibulous celebrations one evening that greatly annoyed the British authorities.12

The men were eager to start flying training, but more disappointment was in store for most of them. Four weeks after their arrival at Oxford, twenty men from the detachment were posted to No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford to begin flying training. The others, however, including Spear, set out on November 3, 1917, for Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire, to attend machine gunnery school. As Parr Hooper, also sent to Grantham, remarked: “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”13

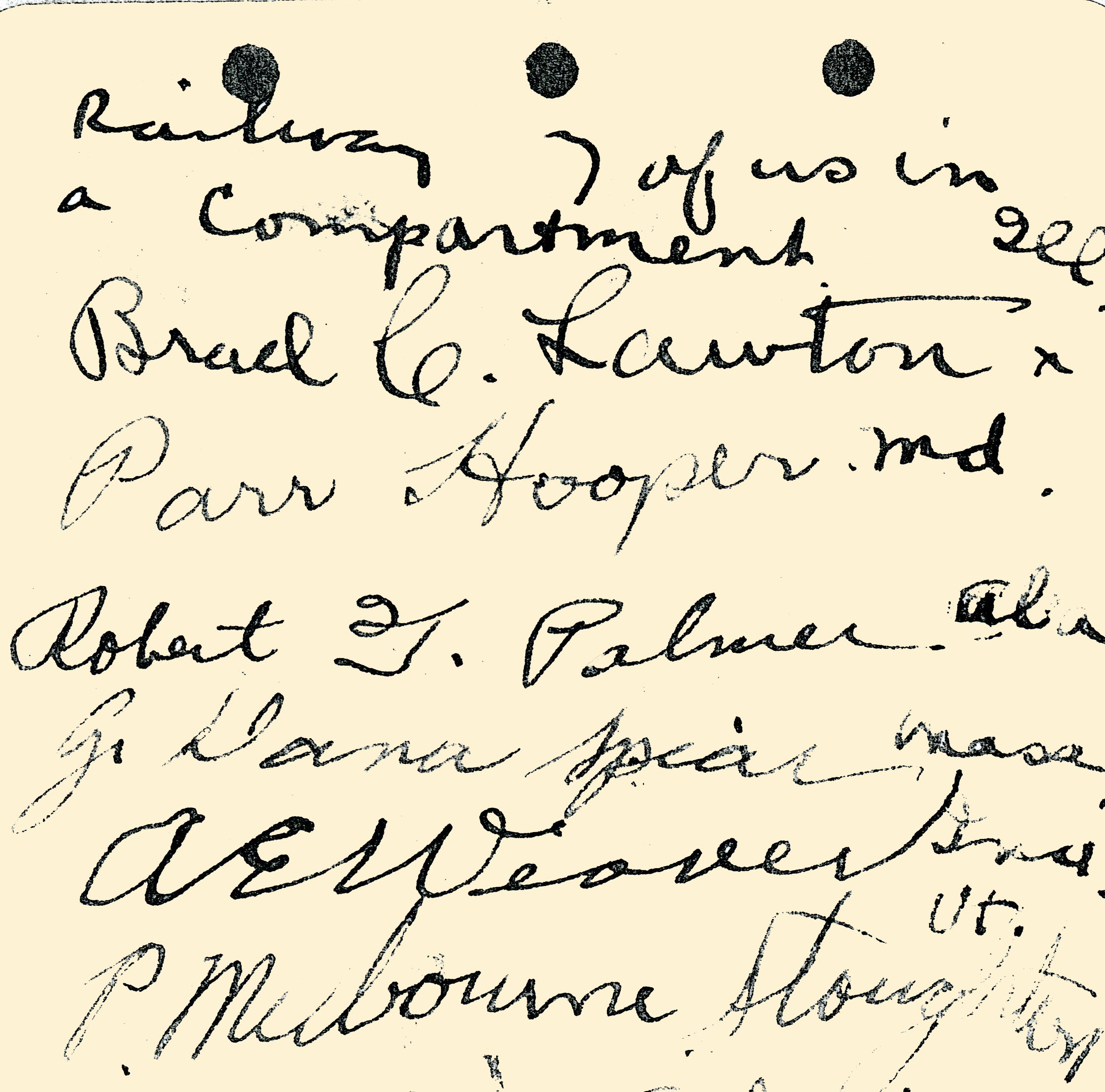

Spear shared a compartment on the train journey to Grantham with Foss, who collected signatures from the men in the compartment—the others were Hooper, Bradley Cleaver Lawton, Robert Thomas Palmer, Stoughton, and Albert Elston Weaver.14 It took about six hours to get from Oxford to Grantham, with an hour’s stop at Bletchley in Buckinghamshire. On arrival at Grantham around 3:30 the men were welcomed with a band and music to which they marched to the camp; there Spear, Foss, Stoughton, and Walter Andrew Stahl were assigned to hut 39, with Stahl in charge.15

At Grantham the men spent their first two weeks learning about and practicing with the Vickers machine gun. In mid-November it was determined that fifty of them could go to training squadrons; Stahl was among the fifty, but Spear, Foss, and Stoughton remained at Grantham and spent the next two weeks on the Lewis gun. As at Oxford, the cadets used their leisure to explore the area; on November 17, 1917, Foss noted in his diary that “Stoughton, Mc[Carthy], Spear and myself went horseback riding.” Plans were also afoot for Thanksgiving, and when the day came, it was celebrated in great style with a football game and traditional meal. The next day, the Grantham cadets learned that they were finally to be posted to squadrons.

While many of the men went from Grantham to training squadrons, Spear was among a large number assigned to various home defense squadrons. H.D. squadrons were tasked with repelling German Zeppelins and Gotha bombers that flew across the Channel and the North Sea to attack Britain. It was evident that cadets were being parked at these squadrons for lack of places at training squadrons, and they would get flying and, perhaps, training, only when the squadron’s duties, planes, and personnel permitted.

The headquarters of No. 33 H.D. Squadron, to which Spear and seven others were assigned, was at Gainsborough, thirty-five miles north of Grantham; its three flights were stationed in the vicinity. On December 3, 1917, William Thomas Clements, one of the men posted with Spear to No. 33, recounted in his diary how he and the others “Left Grantham this morning at 11:30 a.m. Went by train up to Gainsboro’. Waited around about an hour for someone to take us up to headquarters and finally they came. Well, they didn’t know what to do with us after we got up there. The 33rd squadron is a ‘home defense’ squadron and mostly night flying. We were sent out here to Scampton.” Scampton, about eleven miles south-south east of Gainsborough and thus close to Lincoln, was home to No. 33’s A flight. The planes flown were FE2b’s and FE2d’s, “pusher planes,” i.e., ones with the propeller aft of the cockpit.

The next day, Clements recorded having “been in the air. . . . All of the boys had a ride, and some had two.” However, “The pushers are not dual control so all we are getting out of it is riding.” Assuming Spear’s experience at Scampton was like that of Clements, he spent the month of December and most of January 1918 whiling away the time, being taken up for “joy rides” when weather (often inclement) and the availability of pilots and planes permitted, otherwise eagerly waiting for letters and packages from home, playing card games, and making trips into Lincoln. There was a tank factory nearby; Clements recounts a visit to it in his diary entry for December 18, 1917, and this visit may be the one Spear described in a letter home excerpted in an article (“Walpole Boy Drives Tank”) published in the Boston Globe.

Waddington, Bircham-Newton, C.D.P.

In the latter part of January 1918 the men learned that they were finally to be posted to training squadrons.16 Four of them, evidently Spear, Clements, Arthur Paul Supplee, and Weaver, were sent to nearby Waddington. Assuming again that Spear’s training paralleled Clements’s, he would have trained initially on Maurice Farman Shorthorns (“Rumptys”) before moving on to DH.6s. A brief mention in Clements’s diary on March 7, 1918, indicates that Spear was on that date still at Waddington and presumably on course to become a bomber or observation (rather than a pursuit) pilot.

Spear was not recommended for his commission until a month later, and as a “First Lieutenant Aviation Reserve non flying” to boot. This designation does not indicate that Spear was somehow inadequate, but rather points to America’s sluggish and poorly organized preparations for war. In a cable to Washington dated March 13, 1918, General Pershing described the situation of the approximately 1400 aviation cadets in Europe, some of whom had waited three months to start flying training, and some of whom, after five months, were still waiting and might have to wait another four. “All of those cadets would have been commissioned prior to this date if training facilities could have been provided. These conditions have produced profound discouragement among cadets.” To remedy this injustice, and to put the European cadets on an equal footing with their counterparts in the U.S., Pershing asked permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .”17 Washington approved the plan in a cable dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.”18 Thus Spear was among the many men recommended wholesale for commissions as “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying” in a cablegram from Pershing to Washington dated April 8, 1918. It is quite possible that by this date Spear had completed sufficient training at Waddington to qualify to “be transferred” as a flying officer. A cablegram from Washington dated May 13, 1918, included Spear among those whose commissions had been approved, and, finally, at the end of May, he was placed on active duty.19

The only other information I have been able to discover about Spear’s training comes from Caroline Ticknor’s New England Aviators, according to which he went from Waddington to “Bircham-Newton, Norfolk, for work in fighting.”20 This would have been at the No. 3 School of Aerial Fighting—Spear is the only second Oxford detachment member I know of to have done his advanced fighting training there, rather than at Ayr or Marske. The planes available for training at Bircham-Newton included DH.4s, the British version of the plane Spear would fly operationally.21 Once he had completed his training, Spear, according to Ticknor, was posted to the R.A.F.’s Central Despatch Pool and spent an unspecified period of time ferrying planes. Finally, on September 10, 1918, (again, according to Ticknor) Spear was posted to France.

On September 20, 1918, Spear, along with fellow second Oxford detachment members Dana Edmund Coates and Ralf Andrews Crookston, reported to the U.S. 11th Aero Squadron, which was stationed at Amanty, about sixteen miles southwest of Toul.22

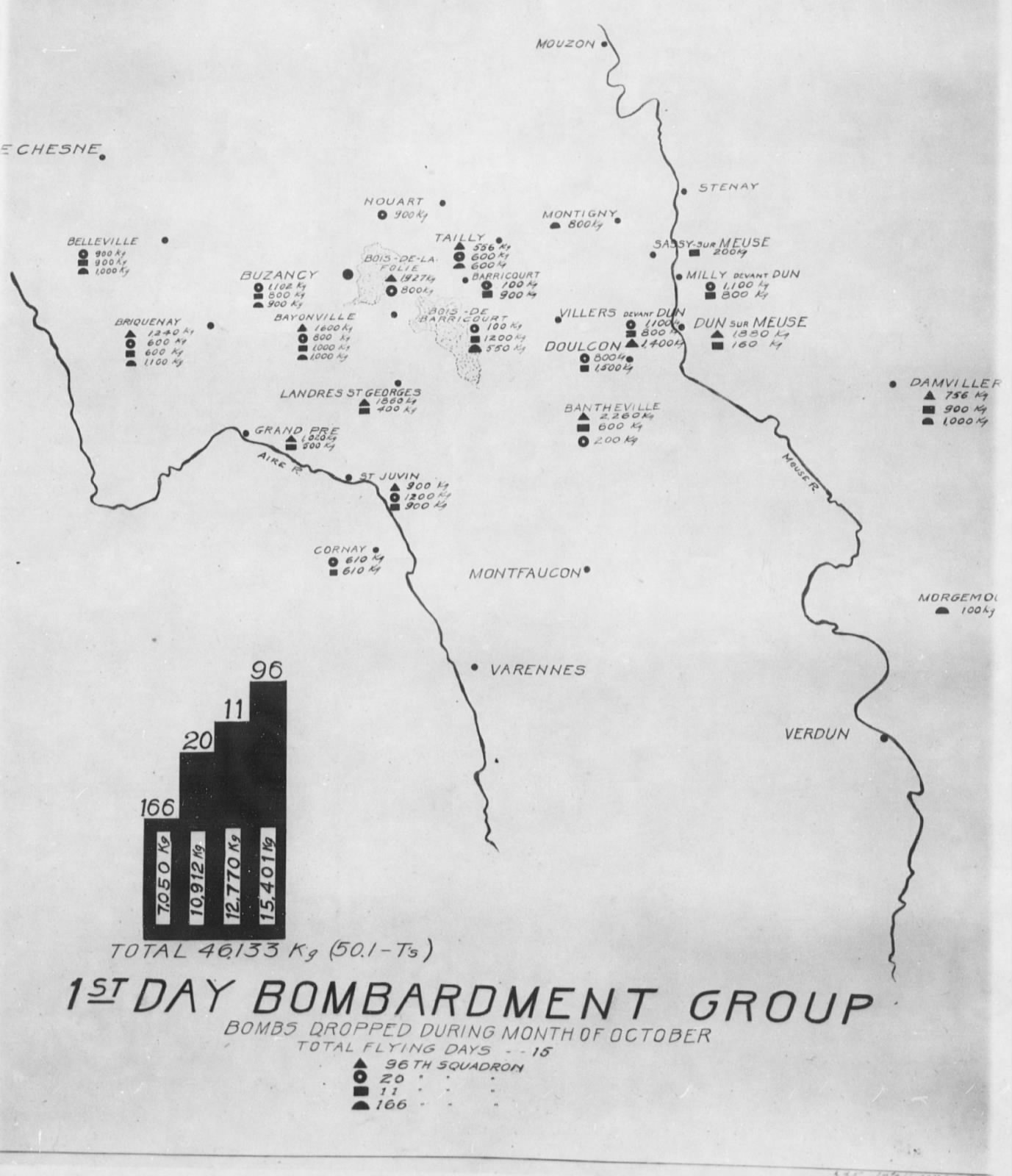

The 11th had arrived in France in mid-August. Its first flying officers arrived on September 1, 1918, and more on the 12th (including second Oxford detachment members Vincent Paul Oatis, Robert Brewster Porter, Fred Trufant Shoemaker, and Spear’s Grantham hut-mate Stahl), but the squadron was still not up to full strength.23 With an insufficient number of planes (DH-4s—the American version of the British DH.4) and pilots, and with most of the pilots inexperienced in combat, the 11th nonetheless joined the 96th and 20th Aero Squadrons to make up the 1st Day Bombardment Group two days before the opening day (September 12, 1918) of the St. Mihiel Offensive, which it was to support. By the end of the day on September 18, 1918, fourteen pilots and observers from the 11th (35% of the roster of officers) had been killed or taken prisoner, including their commanding officer.24 This was the decimated and demoralized squadron that Spear, Coates, and Crookston joined two days later.

The next day, September 21, 1918, a new commanding officer was assigned; this was Charles Louis Heater, another second Oxford detachment member. Heater had by now had considerable experience flying DH.4s with No. 55 Squadron of the Independent Air Force, and between his skilled leadership and the recognition by higher ups that changes needed to be made, the 11th was able to come back from the brink. In a very short period, Heater taught his pilots close formation flying, and the 1st Day Bombardment Group started using larger and thus better protected formations during the Meuse–Argonne Offensive, whose way had been prepared by St. Mihiel.25

On September 24, 1918, the 1st Day Bombardment Group, including the 11th Aero, began moving—unobtrusively, so as not to alert the Germans—from Amanty twenty miles west-northwest to Maulan as part of the extension of the American First Army’s front from the St. Mihiel sector to the Argonne Forest.26 Late in the morning the next day Spear made an hour-long flight as Coates’s passenger; the itinerary, as recorded in Coates’s log book, was “Ligny, Bar-le-Duc, Revigny, St. Dizier and return.” They were evidently familiarizing themselves with the area to the north and west of the new air field.

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive opened on September 26, 1918. The role of the 1st Day Bombardment Group was to disrupt the movement of German troops and supplies by bombing “Troop Concentrations and Convoys,” and “Dumps, Railheads, Camps & Command Posts.”27 They were originally tasked, unrealistically, with targeting sites as far behind the lines as Carignan and Lumes.28 In practice, they were initially able to reach and bomb locations on and near a line running approximately from Grandpré east to Dun-sur-Meuse, all roughly fifty miles north of Maulan.29 Spear’s name, in contrast to those of Coates, Crookston, Oatis, Porter, and Stahl, does not figure in the 11th Aero’s extant standby orders or accounts of missions for the opening day of the offensive or for subsequent days in September

The records indicate that Spear, with observer Cedric James Newby, flew his first mission the afternoon of October 1, 1918.30 The objective was Bantheville, nearly fifty miles due north of Maulan but by now, due to the initial rapid advance of American troops, only a few miles inside the lines. There were to be two formations from the 1st Day Bombardment Group taking off in succession after 3 p.m. Most of the planes in the first formation, Breguets flown by pilots of the 11th and 96th Aero Squadrons, reached and bombed Bantheville.31 The second formation, however, which included Spear, flew, according to the unofficial squadron history, in a very large and impractical arrangement of planes: there was “an unwieldy number of machines and the formation was in fearful shape when they approached the lines.” Additionally, one observer, Ramon Guthrie, lost his helmet and thus his protective goggles. His pilot, Oatis, who was presumably a deputy flight leader, “attempted to get him down from the high altitude and succeeded only in breaking up the entire formation, which followed him mournfully home.”32

The next morning (October 2, 1918), a similar mission was undertaken, again with an initial formation made up of Breguets flown by pilots of the 11th and 96th, followed by a formation made up of twenty-two DH-4s piloted by men from the 11th and 20th Aero Squadrons. The objective, St. Juvin, was about seven miles west of the previous day’s target. Spear, now with observer James Golden Curtin, who would accompany him on nearly all his subsequent missions, flew towards the back of the second formation. They departed Maulan at 9:40 and reached and bombed St. Juvin at 11:25 from a height of 15,000 feet. Apparently all planes of the 11th Aero—thus including that flown by Spear with Curtin—reached the objective, and all returned safely.33

Spear with observer Curtin flew his next (third) mission the afternoon of October 5, 1918; theirs was plane 24, which would be the plane they flew on many of their subsequent missions. Their position was at the back of a formation made up of twenty planes from the 11th and 20th Aero Squadrons. The relevant sources give the objective of this mission variously as St. Juvin, Aincreville, Landres-et-Sainte-Georges, and Doulcon—all in the same general area, east and west of Bantheville. While some of the planes from the 11th, including that of Coates, had to drop out, Spear and Curtin were among those who reached and bombed Doulcon, at 5 p.m.34

Spear and Curtin took part in a mission the next afternoon that again targeted Doulcon, but had to return before crossing the lines. Bad weather precluded flying missions the next two days.35 The afternoon of October 9, 1918, Spear, with observer Curtin, flew his fifth mission, and their plane (no. 24) was one of six, out of ten, that reached the objective, which was once again Bantheville. The next day, the 1st Day Bombardment Group undertook two missions, and Spear with Curtin flew both of them. They were among eight teams (of ten) that succeeded in reaching the objective, Milly-devant-Dun (sic; sc. Milly-sur-Bradon?) shortly after 8 a.m. Having arrived back at Maulan just after 9 a.m., they set out again at 11:25 as part of a three flight formation to bomb Villers-devant-Dun, but were among the teams unable to reach the objective.36

After this a long period of bad weather set in, and the 11th Aero flew no missions from October 11 through October 17, 1918. One mission was flown the next day (with, for the first time, the participation of the 166th Aero), but Spear did not take part. Bad weather again precluded missions from the 19th through the 22nd.

The 1st Day Bombardment Group flew a morning and an afternoon mission on October 23, 1918. On the morning mission, which consisted of planes from the 20th and the 11th, Spear flew for the first and apparently only time with Walter Henry McCarthy; they were among the five teams (of thirteen) from the 11th Aero that were unable to reach the target, Buzancy. Clifford Walter Allsopp, who also had to turn back, noted in his log book “too much climb & no forward speed,” suggesting that for this reason he, and perhaps others, were unable to keep up with the formation. Enemy planes were encountered and engaged by planes of the 11th south of Buzancy, probably after Spear, Allsopp, and the others had left the formation. The afternoon mission, which set out at 1:50, involved planes from all four 1st Day Bombardment squadrons; Spear was again with Curtin in plane 24 on this, his ninth mission. Spear and Curtin were among the teams that successfully bombed Bois-de-Barricourt at 3:50 p.m.37

There followed three days of poor weather. Spear and Curtin, flying plane 15 (which had overheated when Allsopp flew it on the 23rd), took part in the four-squadron mission the afternoon of October 27, 1918, during which enemy aircraft were once again engaged by planes of the 11th. According to Rath’s “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” Spear, along with pilots Coates and Porter, did not reach the target, Briquenay. However, as other sources suggest that Coates did in fact reach Briquenay, it is possible that Rath’s information about Spear is not reliable.38

Spear, with Curtin, flew his eleventh mission two days later, the afternoon of October 29, 1918; this was again a large four-squadron bombing raid. Spear was among the pilots of the 11th Aero who successfully reached and bombed Damvillers—somewhat to the east of previous targets—from a height of about 12,000 feet. The next afternoon Spear and Curtin successfully took part in a mission that involved the 11th, 20th, and 166th targeting “Belleville”—presumably Belleville-et-Châtillon-sur-Bar, a few miles north of Grandpré. The narrative history of operations of the 11th Squadron records that “The formation was attacked at 15:30 by eight enemy planes. All were successfully driven away.”39

Spear did not fly the mission the next day, and there were no missions the first two days of November. Two missions were flown on November 3, 1918, and Spear and Curtin, in plane 24, took part in both. The initial target for the morning mission was Stenay (which had been one of the targets initially and unrealistically proposed for the 1st Day Bombardment Group at the outset of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive). “Nine machines [including Spear’s] got across but found the objective hidden by mist and clouds, so the village of Martincourt, which had been assigned as the secondary objective, was bombed. Accurate burst were observed in groups of warehouses in the town.”40 (Martincourt was even farther north than Stenay.) On the afternoon mission that day, Spear, along with Crookston, was unable to reach the objective (Beaumont-en-Argonne). The same was the case the next day, when Montmédy was targeted.

Spear, with Curtin as his observer, flew his sixteenth and final mission the morning of November 5, 1918; while planes from the 20th and 166th reached the objective, Mouzon, none of the planes from the 11th crossed the lines on this, their final mission of the war.

By mid-January 1919 Spear was evidently at the 2nd Aviation Instruction Center at Tours. Foss—who had been with the 166th Aero before being briefly assigned to the 11th after the Armistice—kept a copy of embarkation orders dated January 14, 1919, that ordered him, Spear, Stoughton, and a number of others to proceed from the 2nd A.I.C. to Angers to prepare for their return to the U.S.40a They sailed from Brest on February 2, 1919, on the La France, arriving in record time at New York on February 9, 1919.41

Spear worked as an electrical engineer in New York before moving with his family to California sometime in the 1940s.42

mrsmcq July 23, 2025

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Spear’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for George Dana Spear. For his place and date of death, see Ancestry.com, California, U.S., Death Index, 1940-1997, record for George D Spear. The photo is a detail from a photo taken, probably by William Ludwig Deetjen, at Oxford.

2 Davis, The Ancestry of Annis Spear, p. 3.

3 See documents available at Ancestry.com.

4 Fuller, Genealogy of Some Descendants of Dr. Samuel Fuller of the Mayflower, p. 43 and passim.

5 See documents available at Ancestry.com.

6 See “State Scholarships.”

7 See Ticknor, New England Aviators, vol. 1, p. 110. The M.I.T. yearbook, Technique, for the years 1915–1917, indicates he was in the class of 1917, as does Ruckman, Technology’s War Record, p. 530. The 1918 Technique, p. 453, indicates he was in the class of 1918.

8 See Spear’s draft registration, cited above.

9 See Ticknor, New England Aviators, vol. 1, p. 110, and “Wants Bands to Help Army Recruiting,” where for “George S. Spear,” read, presumably, “George D. Spear.”

10 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

11 See Foss’s diary for October 2, 3, and 13, 1917, and Deetjen’s diary for October 4, 1917.

12 See Foss’s diary entries for October 13, 22, and 29, 1917. On the partying and the move to Exeter, see the entry for October 22, 1917, in War Birds, and relevant entries in various original diaries, including that of Foss (entries for October 20 and 22, 1917).

13 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

14 Foss, diary entry for November 3, 1917

15 Ibid.

16 See Clements’s diary entries for January 25, 1918, et seq. I have had to deduce who of the eight men went where from various source.

17 Cablegram 726-S (March 13, 1918).

18 Cablegram 955-R

19 Cablegram 1303-R; McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

20 Ticknor, New England Aviators, vol. 1, p. 110.

21 Sturtivant, Hamlin, & Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 121.

22 See the roster on pp. 4–6 of “11th Squadron.”

23 “11th Squadron,” pp. 4–6; see Sloan, p. 239, on the inadequate staffing and equipment and pp. 240–43 on preparation for and participation in the St. Mihiel Offensive.

24 See Sloan’s summary on p. 245 of Wings of Honor and the roster on pp. 248–49.

25 On Heater, see Skinner, “Commanding the 11th.” On the decision to use larger formations, see Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p. 371.

26 The date of the move is given as August 24, 1918, on p. 3 of “11th Squadron”; History of the Eleventh Aero Squadron, p, 89, indicates that the “move was made by truck train on the night of the 24th and the planes flown over the following day.” Oatis’s log book show him flying from Amanty to Maulun on August 25, 1918, but Coates’s log book shows him to have made the flight the preceding day.

27 From orders dated September 18, 1918, issued by Frank Purdy Lahm, reproduced in Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 2, pp. 238–40; here, p. 239.

28 Ibid.

29 See Thomas, The First Team, p. 89.

30 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 115. History of the Eleventh Aero Squadron, p. 163, however, states that Newby flew his first and only mission on October 4, 1918. Neither source is consistently reliable in detail, and I have not been able to determine which is correct in this instance.

31 Information for this and subsequent missions is taken from Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” unless otherwise noted.

32 History of the Eleventh Aero Squadron, p. 163.

33 See “11th Squadron,” pp. 27 and 55, and Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 116–17. The two sources do not agree on all details.

34 See entries for this day in the log books of Oatis and Coates and in Rath, First To Bomb, as well as the relevant entries in “11th Squadron”; and Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations.” The latter, p. 121, names Doulcon and provides the time. See also the entry for this day on p. 150 of “First Day Bombardment Group.”

35 See entries for these days in Rath, First to Bomb.

36 In addition to Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” see the two raid reports for this day on pp. 78 and 79 of “11th Squadron.”

37 See the 11th’s raid report for the morning mission on p. 81 of “11th Squadron,” as well as the operations report on pp. 131– 33 of Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations.”

38 See the raid report on p. 82 of “11th Squadron”; “General Orders, Air Service, First and Second Armies, American Expeditionary Forces, Confirming Air Service Victories over Enemy Aircraft,” p. 123; as well as the summary provided on p. 36 of Gutmann, “Slaughter in the Sky.”

39 “11th Squadron,” p. 57.

40 History of the Eleventh Aero Squadron, p. 173.

40a Harbord, “Embarkation Orders # 14: Extract.”

41 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for officers on S. S. La France, where, for some reason, Spear is given the rank of 2nd Lt.

42 See records available at Ancestry.com.