(Rochester, NY, June 1, 1887 – Rochester, NY, August 28, 1971).1

Castle’s father, the descendant of Scots-Irish immigrants and son of a prominent Philadelphia Baptist clergyman, founded the Wilmot Castle Company in Rochester, N.Y., which became an important manufacturer of medical equipment; the family was socially prominent in Rochester.2 On his mother’s side Castle could trace his line back to a Revolutionary War soldier.3 Also on his mother’s side, Castle was descended from Stephen Vail, who was the founder of Speedwell Ironworks in Morristown, N.J., and on whose estate his son Alfred Vail and Samuel Morse developed telegraphy.

Castle attended the University of Rochester briefly (1905–06) without graduating, and then worked for about a year in the construction department of the Norfolk and Atlantic Railroad Company in Norfolk, Virginia.4 In 1908, through the peculiarities of Stephen Vail’s will, Castle came into a substantial inheritance.5 In the same year he married Anna Louise Van Wickle; they lived in Puerto Rico where he grew and exported pineapples and citrus fruit.6 He was still in Puerto Rico when the U.S. entered the war on April 6, 1917, but returned to Rochester in May, where he registered for the draft; shortly thereafter he enlisted.6a His wife had gone to Europe the previous year to do volunteer hospital work.7 Castle attended ground school at M.I.T., graduating August 25, 1917.8

Along with about one third of his ground school classmates, Castle chose or was chosen for flight training in Italy, and he joined the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departed Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England, and Castle spent the month of October repeating ground school at Oxford’s School of Military Aeronautics.

On November 3, 1917, Castle travelled with most of the detachment to Grantham in Lincolnshire where they attended machine gun school at Harrowby Camp. There he shared a hut with Henry Bradley Frost, Edward Addison Griffiths, Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, Melville Folsom Webber (all of whom had been with him at M.I.T. ground school), Parr Hooper, Thomas M. Nial, and Edward Russell Moore..9 Hooper took a photo of Castle standing just outside the hut, and Joseph Kirkbride Milnor took one of him with hut mates Hamilton and Griffiths. Fifty of the men left Grantham November 19, 1917, for flying schools, but Castle was among those who remained at Harrowby Camp.10

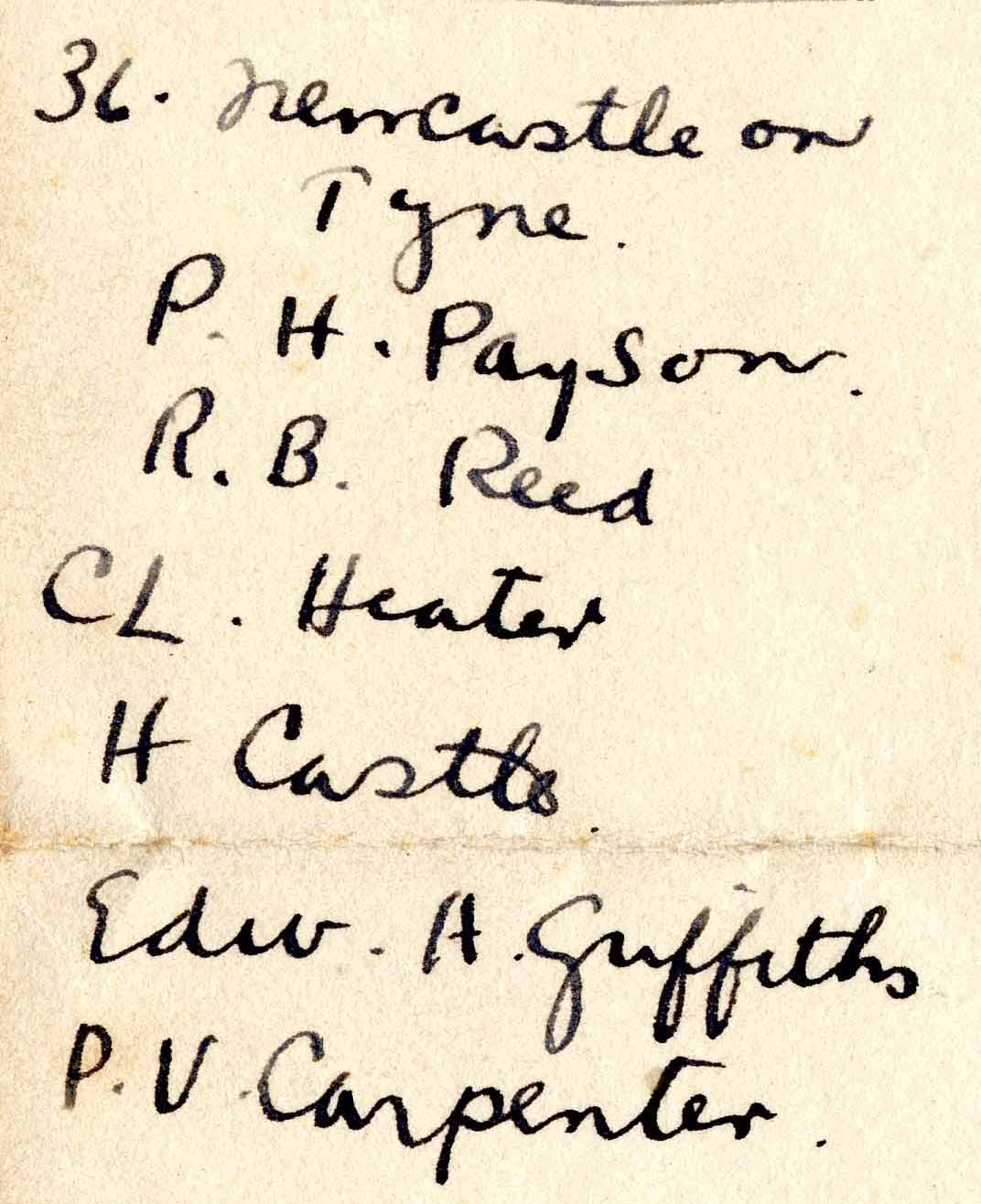

Soon thereafter, however, on December 3, 1917, according to a list drawn up by Fremont Cutler Foss, Castle was one of the six men posted to No. 36 Squadron, a home defense squadron based in and around Newcastle and flying F.E.2d’s.11 Foss, in a diary entry for January 12, 1918, remarks “Castle was here as a passenger in an F.E. on his way to Newcastle. He said their crowd had had no instruction thus far; they were just marking time and fed up.”

There is apparently no R.A.F. service record for Castle, and little information on his training after Grantham. By sometime in the first half of March 1918 he had evidently completed the requirements to be recommended for a commission; Pershing forwarded the recommendation to Washington on March 16, 1918; a cable dated April 6, 1918, confirms Castle’s appointment as a first lieutenant.12 When Castle was placed on active duty on April 17, 1918, his station is listed as “Amesbury,” and this would accord with his probably having trained on Handley Pages at the No. 1 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping at nearby Stonehenge.13

On about July 20, 1918, Castle began serving with No. 216 Squadron R.A.F., the only man from either Oxford detachment to be assigned to 216.14 No. 216 was a night bomber squadron and at this point part of the Independent Air Force. The I.A.F. had come into existence the previous month and, operating independently of the other forces, was to undertake bombing of aerodromes, railroad transport, and industrial centers inside Germany.14a When Castle joined it, No. 216 Squadron was at Ochey, about twelve miles west-southwest of Nancy, in Lorraine.15 The Squadron was equipped with Handley Page Type 0/100 bombers, two-engine biplanes that could carry a crew of four as well as sixteen 51 kilogram bombs; Handley Pages were capable of flying for up to eight hours.16

Castle took part in bombing raids shortly after arriving at Ochey, serving as gunner on a raid on Rastatt in Baden on July 29, 1918, and again on July 30, 1918, in a raid on Stuttgart. He continued to serve as gunner in a number of raids in August, including one the night of the 21st–22nd on Cologne, a round trip of about 420 miles and nearly eight hours. In early September 1918 Castle began serving as pilot on bombing missions, with trips on September 2 and 3 to drop bombs on Boulay Aerodrome; on one occasion (September 2, 1918) he had two observers, Bernard Alexander Levy and G. W. Fields, with Sherwood Hubbell as his gunner; the next night he had with him Levy and Hubbell.17

The St. Mihiel Offensive began on September 12, 1918, and the I.A.F. was asked to assist by focussing on targets on the Lorraine front; bad weather to some extent restricted effectiveness.18 But it was presumably as part of this effort that Castle, again with Levy as his observer and Hubbell as his gunner, took off, on the evening of September 14, 1918 (I have not found an account that indicates what their objective was). Their fellow squadron member and squadron historian Edward Delta Harding recorded the following:

The machine [Handley Page 1459] was returning on the night of 14th September 1918 from an attempted raid and forced landed [sic] at Maron (N.W. of Pont St. Vincent). It crashed and caught fire. Lieut. Castle and Lieut. Levy were rendered unconscious. The latter was extricated by Lieut. Hubbell, himself severely shaken, and carried to a safe distance. Lieut. Levy recovered consciousness and volunteered to return with Lieut. Hubbell to the machine, which was now blazing, in order, by combining their efforts, to drag out Lieut. Castle. The flames had spread as far as the fuselage, and the bombs might have exploded at any moment. They went back and after some difficulty recovered Lieut. Castle and carried him to a safe place. He was still unconscious. Lieut. Levy, it was found later, had a fractured ankle, and in addition was badly cut about the head.19

For his actions, Hubbell was awarded the Silver Medal by the Society for the Protection of Life from Fire and was mentioned in dispatches.20

Castle was apparently admitted to the Eighth Canadian Stationary Hospital at Charmes; a newspaper article from mid-October reported that he “has just been ordered back to England to organize an American squadron there.”21 It is more probable that he was to return to England to act as an instructor; Americans were attached to the night bombardment squadrons of the I.A.F. on the understanding that they would remain there until “efficient enough to act as instructors to Americans in that branch.”22 He is listed among those expected to join the Handley Page night bombing instructional staff as “monitors” at Ford Junction in England in a report on the American Night Bombing Section in England.23 In a “List of Officers Who Have Demonstrated Exceptional Ability in Night Bombing” that was probably drawn up in December 1918, his name is included, and he is described as “Instructor on Handley Page at Ford Junction. Passed thru 9th A.I.C.”23a

At some point during his time in England, Castle apparently fell ill. When he sailed for the U.S. from Southampton on February 27, 1919 on the Mauretania, he was part of a small “convalescent detachment” of officers from American Red Cross Hospital No. 22 in London, and on arrival in New York on March 6, 1919, he was sent to Lafayette House, the officers’ annex of Debarkation Hospital No. 5.24 His officer’s card in New York’s Abstracts of World War I Military Service indicates that he was twenty percent disabled when he was discharged October 19, 1919, while noting “wounds received in action: none.” This suggests his disability was not related to the injuries from his crash.25

Castle joined the family business in Rochester, eventually becoming first vice president of the company.26

mrsmcq May 24, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Castle’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Harvard Castle. For the date and place of his death, see Mount Hope NY, “Harvard DeHart Castle.” The photo is taken from “Then and Now—Harvard Castle.”

2 See, for example, Dau’s Blue Book for 1904, p. 20; and Leonard, Men of America, p. 410.

3 See Quinby, Genealogical History of the Quinby (Quimby) Family in England and America, p. 166 and passim.

4 The University of Rochester, General Catalogue, p. 145.

5 See “In New Jersey.”

6 “Castle–Van Wickle.”

6a Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, record for Harvard Castle; Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917–1919, record for Harvard De H Castle.

7 Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Anna Van Wickle Castle (1916).

8 See “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

9 See Hooper, Somewhere in France, annotation to letter of November 4, 1917.

10 Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917.

11 “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers. On 36, see See Philpott, Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 402, and Wikipedia, “RAF Usworth.”

12 See cablegrams 739-S and 1049-R.

13 Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.” The “Report on the Activities of the Mobilization and Training Department of the Night Bombardment Section, Air Service, American Expeditionary Force,” p. 9, notes that some American pilots sent to the I.A.F. had been trained at Stonehenge.

14 See “List of American Fliers who Served with the Independent Air Forces” and Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 219 (where for “Howard deH. Castle” read “Harvard deH. Castle”), both of which put him at No. 216 on July 20, 1918. His casualty form (“Lieut. H Castle USAS”), indicates he was assigned on July 18, 1918.

14a There is considerable controversy surrounding the I.A.F. Chapter 11 of Wise’s Canadian Airmen and the First World War provides an account and an assessment based on original documents that is worth reading.

15 Harding, A History of Number 16 Squadron, Chapter 6.

16 Herris and Pearson, Aircraft of World War I: 1914–1918, p. 174.

17 Harding, A History of Number 16 Squadron, Chapter 5. I cannot tell whether the list of raids Harding provides is complete, i.e., whether there may have been missions not noted by him that Castle participated in.

18 See Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, p. 218.

19 Harding, A History of Number 16 Squadron, Chapter 8. The casualty card for Castle for this incident locates the crash at “Bois le Viques”—which I have not been able to find. See “Castle, H.” (Levy’s casualty card simply says “France”; see “Levy, B. A.”)

20 Harding, A History of Number 16 Squadron, Chapter 8; and “Mentions . . . Officers,” p. 102.

21 “Two Killed, One Missing and Six Wounded Men of City on Casualty Lists.”

22 “American Fliers with the I.A.F.,” p. 117; see also pp. 140 & 141 on plans to return Castle to England.

23 “Report of the Activities of the . . . Night Bombardment Section . . . ,” p. 10; the list appears to date from August 28, 1918, and plans could, of course, have changed by the time Castle returned to England.

23a “List of Officers Who Have Demonstrated Exceptional Ability.”

24 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Harvard DE R. Castle [sic].

25 Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917–1919, record for Harvard De H Castle.

26 “Million Dollar Plant.”