(Philadelphia, October 13, 1893 – Bruville, France, September 19, 1918)1

Oxford & Grantham ✯ No. 50 H.D. Squadron ✯ 5 T.D.S. ✯ 5 T.S. Wyton ✯ Marske & Chattis Hill ✯ France

One of Hilary Baker Rex’s ancestors was German-born farmer and blacksmith Hans Jürg Rüger, who settled in Chestnut Hill (now part of northwest Philadelphia) in the early part of the eighteenth century; the variously spelled last name was changed to Rex.

Hilary Baker Rex’s father, Walter Edwin Rex, was a prominent Philadelphia lawyer; his mother, the former Isabel Tolbert Emory, was descended from a Philadelphia mayor, Hilary Baker. Hilary Baker Rex had an older sister and a younger brother; another, older, brother died young.2 Rex’s father succumbed to heart trouble in the summer of 1916.3

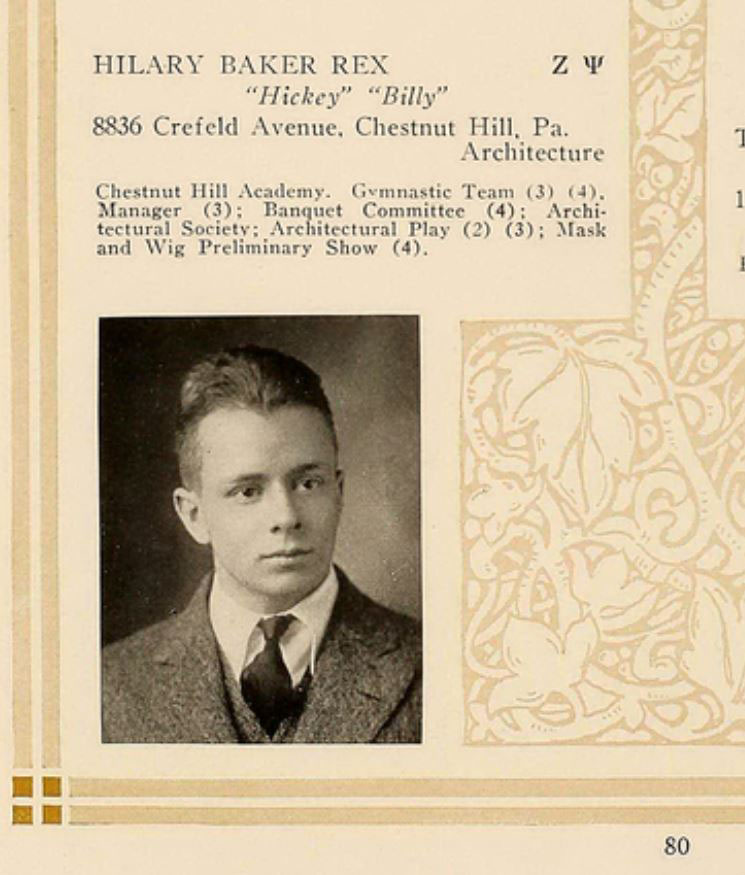

Rex attended the Chestnut Hill Academy before enrolling at the University of Pennsylvania, from which he graduated with the class of 1916 with a degree in architecture. He joined the Philadelphia architectural firm of Brockie and Hastings, but in the spring of 1917 left for the officers training camp at Fort Niagara, New York.4 Having evidently applied for and been accepted by the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps, he went to the School of Military Aeronautics at Cornell and graduated from ground school there on September 1, 1917.5

Rex, along with most of his ground school classmates, including Clark Brockway Nichol, who had been at Ft. Niagara and Cornell with him, chose or was chosen to continue training in Italy. A few days after ground school graduation, Rex left for Mineola on Long Island to await further orders. He was able to get in a brief visit home before the 150-man strong “Italian detachment” proceeded to the west side of lower Manhattan on September 18, 1917, where they boarded the Cunard line’s Carmania and set sail. The initial port of call was Halifax, where they arrived the morning of September 20, 1917. The next day the Carmania set out as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing. Like a number of second Oxford detachment members, Rex started keeping a diary, not writing every day, but frequently enough to provide a reasonably detailed record.6 Much of what follows is based on the diary.

On the 22nd, Rex wrote that “We are getting into a routine now. Calisthenics at 11.30 A.M. (breakfast at 9.00 AM), lunch at 1.30 P.M., boat drill at 4.30 P.M., dinner at 7.00 P.M. & Italian classes from 8.30 – 9.30 P.M.” Italian was being taught by Fiorello La Guardia, also bound for Italy; the cadets travelled first class and were treated very well. On Sunday the 30th, after several days of no entries, Rex wrote that “Things have been going on the same as usual except that Friday . . . they started the submarine watch, this detachment having been picked to do the watching.”

The Carmania passed safely through the dangerous coastal waters and docked at Liverpool early in the morning of October 2, 1917. Rex wrote in his diary that they “Disembarked about 11 o’clock and then Gloom of Glooms we found that our orders were changed and that we had to go to Oxford ground school for six weeks and the Italy trip was off. Such is life in the army. The Major [Leslie MacDill] has gone to Paris to see if he can get us out of this, but there doesn’t seem to be much hope. I never thought I would be an Oxford Don.”7

Oxford & Grantham

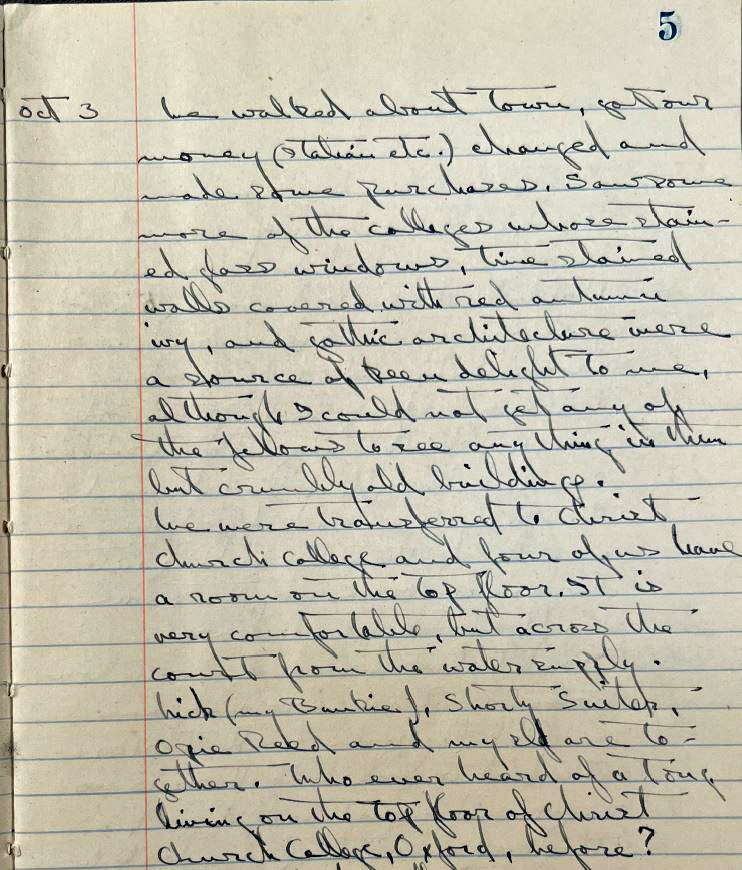

At Oxford the cadets were provisionally assigned to various Oxford colleges for their first night. Rex was in Lincoln College, whose architecture he appreciated, although he was dismayed by its decrepitude (“the limestone walls are hanging in flakes”8). The next day the men received more permanent assignments to Christ Church College and The Queen’s College; Rex was in a room on the top floor of Christ Church: “Nick (my Bunkie), Shorty Suiter, Opie Reed and myself are together”9—Nichol, Wilbur Carleton Suiter, and Richard Brumback Reed had all been in Rex’s ground school class at Cornell.

Having arrived at Oxford after the beginning the week’s classes, the men waited until the following Monday to begin instruction at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics. A few days into the new week, Rex wrote that “So far we have had nothing new in school except different engines. The course here is better systematized than ours was.”10 Relief from tedium was provided by rowing on the Thames and exploring Oxford and the surrounding countryside, and, about two weeks into the course, by being reassigned to rooms in Exeter College. This came about when, the evening of Saturday, October 20, 1917, “they wouldn’t let us out, but somehow or other nearly everyone managed to get drunk. The Colonel [Bertram Richard White Beor, Commandant of the Oxford S.M.A.] caught someone in the Queen’s Squadron out without a pass, so he went back & got them all out of bed at 11:30 and had a formation. They were all so drunk they could not stand in line, but passed out right and left. The Colonel is rabid and wants to can the whole crowd. I don’t think anyone would mind much.”11 Beor eventually calmed down, but insisted that all the Americans be segregated from the other R.F.C. cadets and housed in Exeter College.

The men remained at Oxford for four weeks, not six, but this was small consolation, as nearly all of them, including Rex, were posted in early November not to flying squadrons for training as they hoped, but to a machine gunnery school, Harrowby Camp, northeast of Grantham in Lincolnshire.12 On the plus side, as Rex noted in his diary several days after arriving at Grantham, “They are treating us royally here. We have a mess of our own and the meals are better than those on the Carmania. The quarters are very comfortable. I am in what they call a ‘hut’ with seven other fellows.”13 His “hut mates” initially were Wendell Ellison Borncamp, George Atherton Brader, Ralf Andrews Crookston, Burr Watkins Leyson, Nichol, Donald Swett Poler, and Donald Andrew Wilson; Lloyd Ludwig joined them partway through the month.14 Rex thought the machine gun course interesting, but found he was “beginning to agree with Goody [Weston Whitney Goodnow] that this is a ‘jaw-bone war.’ It is as far as we are concerned anyway.”15 Rex spent some of his evenings going on walks with Goodnow and also went out twice to “run with the Harrowby beagles”16—“beagling,” following the hounds on foot rather than on horseback, is an activity also mentioned by second Oxford detachment member Francis Kinloch Read during his time at Grantham.17

In his diary entry for November 17, 1917, Rex noted that “50 of the fellows are being posted to flying schools on Monday [November 19, 1917]. The rest of us stay here and take the Lewis gun now that we have finished the Vickers. Goody is going so I guess I’ll have to find some one else to take walks with nights.” Suiter stepped in as his walking partner. Towards the end of the month Rex was finding that “Four weeks in one place is long enough.”18 Thanksgiving provided a diversion; there was a lively American football game followed by a feast.

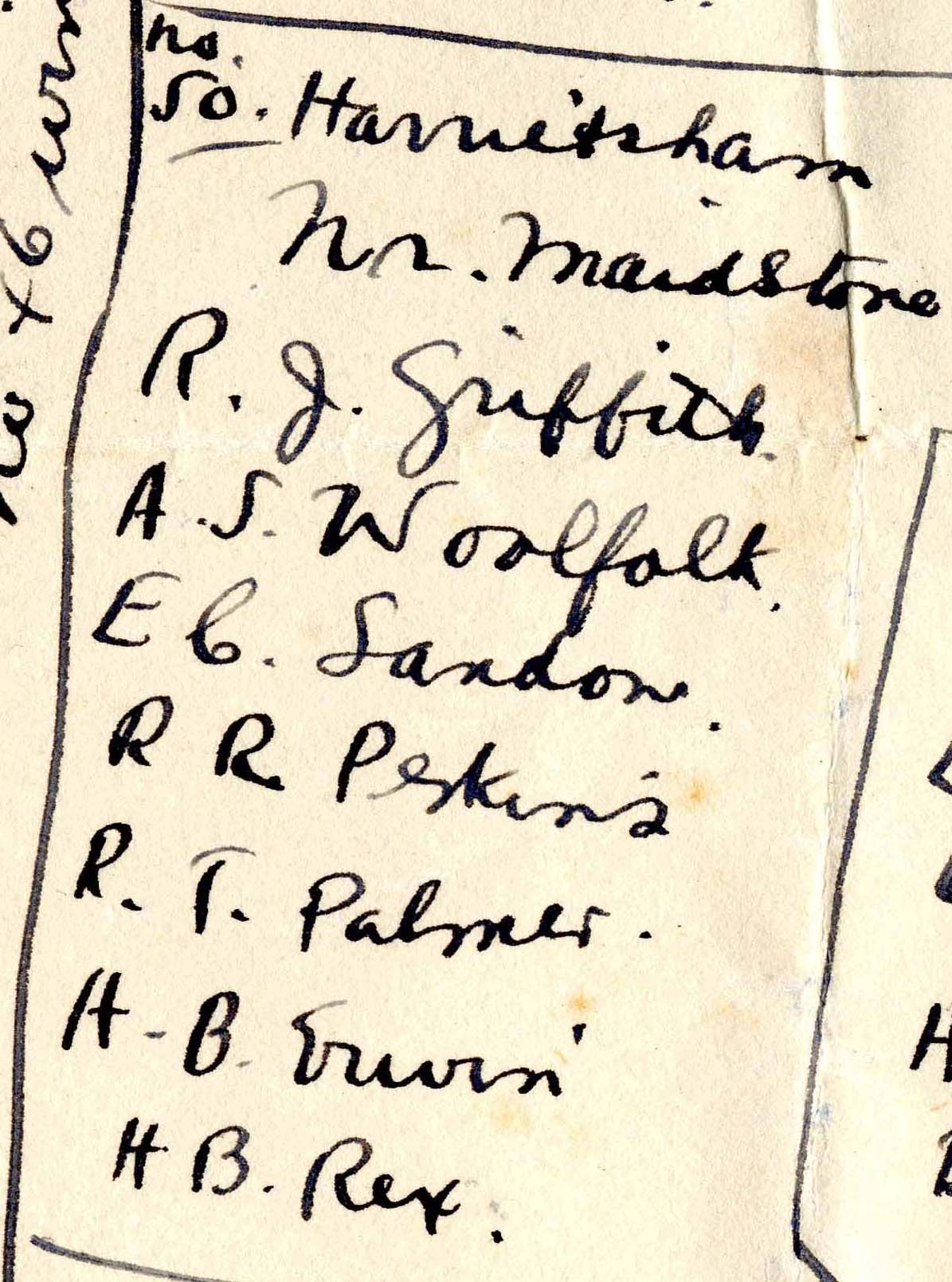

The Lewis machine gun course finished up the morning of Saturday, November 1, 1917. The next day was taken up with preparations for departure from Grantham: “We are being posted to flying schools Monday. I go to 50th Training Squadron, Harrietsham, near Maidstone, with a bunch I don’t know at all.” The “bunch” was Robert Jenkins Griffith, Harrison Barbour Irwin, Edward Carter Landon, Robert Thomas Palmer, Pryor Richardson Perkins, and Albert Sidney Woolfolk, who had all been at ground school at Ohio State University together.19

No. 50 H.D. Squadron

The seven cadets were not in fact being sent to a training squadron, but rather, as Rex soon discovered, to a home defense squadron. No. 50 Squadron’s aircraft at the turn of the year included the B.E.2e and the A.W. FK.8, both two-seaters used for reconnaissance and bombing, and the B.E.12b, a single-seater night fighter; there were apparently no planes at No. 50 designed for training when the men arrived.20

The squadron’s headquarters was at Harrietsham in Kent, but its flights were at this time detached to Bekesbourne and Detling.21 Griffith, Irwin, and Woolfolk went to C flight at Bekesbourne near Canterbury, while Rex, along with Landon, Palmer, and Perkins, was assigned to B flight at Detling.22

On December 5, 1917, Rex wrote in his diary that it “Doesn’t look as though we would get any flying instruction here.” The cadets did, however get some time in the air. In the same diary entry Rex wrote that “They took me up for a flip in an A.W. this morning and we were up about three quarters of an hour. . . . I was tickled to pieces with the flip, but I want to fly one myself.” In mid-December “The captain says we may have some dual control soon,” and early in the new year, Rex recorded in his diary that he had “been up twice on dual control in the last week. Have not got the feel of it yet very much, but I think I will soon.”23 A week later he wrote that he “Did some dual take offs and landings last week.”24 Rex, like Palmer and Perkins, does not record flights made at Detling in his pilot’s flying log book—and they did not count towards his accumulation of flying hours—so there is no record of what plane was being used.

Shortly after Rex arrived at Detling there was an air raid. In the very early hours of December 6, 1917, “The readiness signal came thru, the flight got out of bed with much cursing and in an incredibly short time the flares on the aerodrome were blazing and we had 4 planes up. By that time the archies were blazing away all around the horizon. The Huns were over in Gothas and one flew over the aerodrome. Our planes came in one by one without having seen anything and we went to bed about 5.30.”25 Two of the Gotha bombers succumbed to anti-aircraft fire (“archie”), one coming down at Rochford in Essex, the other near Canterbury.26 Rex was among those who went to inspect the one near Canterbury, and he took the opportunity to look at the Cathedral and make notes on its architecture.

Otherwise, there was not a great deal to occupy the American cadets at Detling. Rex took “some long walks with [Thomas Emsley] Garside dud afternoons”; Garside was also his companion in excursions to Maidstone for dinner and the movies.27

On January 19, 1918, Rex wrote that “The C.O. says we leave here soon for a regular training squadron,” but it was not until January 28, 1918, that he, along with Palmer, Perkins, and Landon, arrived at Stamford. The next day they went to No. 5 Training Depot Squadron at Easton on the Hill about two miles south-southwest of Stamford.

5 T.D.S.

Initially the men were “billeted in what is known as ‘the cottage.’ It is a nice cottage—for cows. . . . No water except what the batman brings in a bucket from a water cart in the front yard.”28 A good mess offered some compensation, as did the fact that “Nick and Shorty Suiter and quite a few of the Italian Detachment have shown up here.”29 Towards the end of February Rex and his mates moved from Easton on the Hill to an old isolation hospital on the eastern edge of Stamford, “an old tin [?] place that looks like nothing on earth, set out in a lumpy field on the edge of a dump with a brick factory in back and a cemetary [sic] on one side.” Rex was glad they at least still had their “trusty batman.”30

The first week at 5 T.D.S. was spent on the ground in classes (“same old stuff, buzzer, M.G.”).31 Rex went on his first instructional flight of twenty-five minutes the afternoon of February 7, 1918; the plane was a B.E.2e ([B?]9993).32 The pilot was Wilfred Lawry MacIlwraith; it apparently did not bother Rex that his first instructor was nineteen, five years younger than himself—or at least he does not mention it in his diary.33 He was concerned only that the weather was “rotten and probably would be for two months.”34 This prediction notwithstanding, he flew again on the 11th and 12th, and twice on the 15th, now with the slightly older George Eastwood.

Three days later, on February 18, 1918, Nichol, who had trained with Rex at Ft. Niagara and Cornell and roomed with him at Oxford, was killed at 5 T.D.S.: “Poor old Nick has gone west. Got into some sort of a spin to-day and dove straight into the ground from about 200 feet in a BE2e. He was smashed to pieces and the plane is a write-off.”35 Rex had the sad duty of writing to Nichol’s mother and, on February 21, 1918, he, along with John Joseph Devery, Landon, Perkins, Suiter, and Woolfolk, served as a pall bearer at Nichol’s funeral.36

Rex was shaken by his friend’s death, as well as by the other fatalities and crashes among men he knew; nevertheless by early March frustration at how little flying he was able to do became the theme of his diary entries: “I’m fed up! I’m supposed to be on BE’s and there are never any running or else the weather’s rotten. There’s always something. I’ve hardly been off the ground for three weeks.”37 There was also the question of when he would finally receive his commission, but, as Rex noted in the same diary entry, “[John Warren] Leach has his commission so things in that quarter don’t look quite so hopeless.” However, Leach had arrived at 5 T.D.S. from a training, rather than a home defense squadron, so he had a considerable advantage over Rex.

Things improved dramatically a few days later, when Rex was able to put in several hours of dual flying with Eastwood, with particular attention to landings. Then, on March 12, 1918: “O memorable day! I went solo this morning—and made one priceless landing and one rotten one.” By March 21, 1918, he had put in a little over nine hours solo and had completed his height test, one of the requirements for graduation from this stage of R.F.C. training: “8000 ft. for 15 min. then switch off and glide down.”38 Five days later he flew solo to Wyton and back in a B.E.2e, completing another graduation requirement, a cross-country flight, and his number of solo hours (16 hours and 25 minutes) was now more than double the number of hours he had flown dual.

In the meantime Rex apparently experienced his first crash, a minor one. In his diary for March 29, 1918, he wrote: “Last week I stood a B.E. up on its nose in the middle of the ’drome—the flight it belonged to were awfully fed up about it. Only broke the prop.”

Rex went up in an R.E.8 for the first time on March 22, 1918, flying dual with Eastwood, and again several times in April in preparation for the final graduation requirement, flying an operational aircraft (such as the R.E.8) solo. Flying an R.E.8 at this point was not in itself predictive of the type of plane a pilot would fly operationally: men who graduated on R.E.8s went on to fly both scouts and observation / bomber planes. But Rex wrote in his diary on March 29, 1918, that “They say now we’ll probably go on R.E.8s—that means Art[illery] Obs[ervation].—rotten.” Rex, like many of his fellow pilots in training, presumably was hoping to fly scouts.

Bad weather (fog) meant that Rex spent a good many days in April on the ground. Once the weather had improved towards the end of the month, he put in many hours flying dual, mostly with Eastwood, but also with Peter Dudley Stuart and Alan Carnegy Horsbrugh, practicing aerial photography, various types of turns, and forced landing.

In April Rex’s living situation at Stamford changed yet again, this time for the better. He had become good friends with Clayton Joseph Knight, who had also been posted to Stamford at the end of January, and the two of them moved into “a room together over the baths”39—this was The Baths at 16 Bath Row, the home and business establishment of Mrs. Ingle in Stamford; her previous roomers had included second Oxford detachment members William Ludwig Deetjen and Linn Humphrey Forster. “The Ingles are very good to us. They let us have a fire whenever we want and hot water and baths free.”40

In early April Rex, Knight, and many others, were, finally, recommended by Pershing for their commissions—but as “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying.”41 Earlier in the year it had been brought to Pershing’s attention that many cadets had been held up in their progress towards commissions by the limited training facilities. On March 13, 1918, he had cabled to Washington requesting permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .”42 Washington approved the plan in a cable dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.”43 Hence the “non-flying” status attached to Rex’s commission recommendation in the April 8, 1918, cablegram. It took over a month and some prodding, but finally, on May 13, 1918, Washington cabled back approval.44

Coincidentally, Rex graduated from this stage of R.F.C. / R.A.F. training the next day (the Royal Flying Corps became the Royal Air Force on April 1, 1918). Despite having fulfilled most of the requirements for graduation in March, it was not until May 9, 1918, that he flew an R.E.8 solo, thus completing the final graduation requirement.

Rex’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card shows him to have graduated on May 14, 1918—it is not clear why the graduation date did not, as usually happened, coincide with his first solo flight in an operational aircraft.

While at Stamford, Rex and Knight made excursions to Nottingham together and, now, having graduation leave, again spent time there. Rex also spent some of his leave in Sheffield, staying with the family of James Paton Auld, a civil engineer who had spent part of the war working in the U.S. for the British government.45

On returning to Stamford “they told me to get ready to leave as I was posted to Wyton to fly DH9’s. Was in a hectic stew for a while with red tape and collecting my junk, but finally got off with [Robert Brewster] Porter, Woolfolk, and Perkins.”46 Rex’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card gives the date of this posting as May 23, 1918.

No. 5 T.S. Wyton

Rex once again initially had bad luck with accommodations: “They put us under canvas and the first night I slept on the windward side of the tent. It rained like stink and all my things were soaking in the morning. It would be like that.”47 However, flying DH9s (“Priceless busses! 110 miles per hour on the level”48) was some compensation. Rex made his first flight at Wyton on May 26, 1918, in DH.9 [D]5562, flying dual with William Petre for forty-five minutes, practicing turns and landings. In the afternoon he again went up dual with Petre, this time in a D.H.6 (a plane designed for training) and immediately afterwards took the same plane [D]6549 up for ten minutes solo. The next morning, after another long dual flight in a D.H.9 with Petre, he made his first solo flight in a D.H.9—ten minutes in [C]2165; another solo flight the next afternoon in the same plane might have been longer but that the “engine cut out.”49

There was very welcome news at the end of the month: “our commissions came through in a bunch . . . at last! I don’t believe anyone at home realizes how we have waited for them and thought each month that they would come—or that they would never come.”50 It had taken from May 13, 1918, the date of the cablegram from Washington approving the commissions, until the end of the month for the news to trickle down; Rex was, finally, placed on active duty on May 30, 1918.51 “Now that [my commission] has come I find that I have gotten used to it—[lieutenant’s] bars, Sam Browne [belt], wings and all—very quickly. I’m even getting sick of being saluted already.”52

Also on May 30th, which was Decoration (Memorial) Day, “we had a half holiday and I went to Stamford and stayed at my old billet with the Ingles. Had a corking time. I feel now that I have a ‘home away from home without hymns’ as the saying goes.”53

Rex remained at Wyton through the first two weeks of June, adding many solo hours flying in B.E.2e’s and DH.9s; at the end of his time there he had forty-four hours and forty minutes of solo flying in addition to his eighteen hours and twenty-five minutes dual. On June 6, 1918, he passed another height test, flying DH.9 [C]2165: “went up to 15000 ft. this PM and had a gorgeous time. It seems like the threshold of another world up there.”54 Three days later, “They tell me I will go to Marske (Aerial Gunnery School) about the 11th. I’m certainly getting out of here quickly.”55 This was optimistic; it wasn’t until June 17, 1918, that he set out with Harvey Donald Spangler and second Oxford detachment member Albert Elliott Parrish for Marske-by-the-Sea in north Yorkshire.56 During his last few days at Wyton, “I’ve been ferrying busses between here and Thetford. Saw Clayton Knight twice. Wish he was going to Marske with me.”57

Marske & Chattis Hill

The first week at No. 2 Fighting School was devoted to class work again: “same old stuff with some of the hot air extracted,” as Rex described it in his diary entry for June 18, 1918. Soon he had “finished ground work and have been flying practically for the last two days—fighting other busses and doing formation.”58 Rex’s first flight at Marske, on June 24, 1918, was in an Avro, when he was tested by instructor William Buckingham. By the end of day on June 28, 1918, he had put in nine and a half hours of flying “solo”—which is to say, he was piloting, but now always with a passenger, usually an unnamed mechanic, but on one occasion Parrish.59

It was Rex’s understanding that his next posting would be Stonehenge, i.e., the School of Bomb Dropping and Navigation in Wiltshire. It turned out he would indeed be in Wiltshire, but at the Chattis Hill Wireless Telephony School. He and Parrish, “(after the usual hours of red tape) managed to get away from Marske” on June 29, 1918, and travelled to London, before reporting to Chattis Hill. They had a busy, enjoyable day in London: “No one knows where we are and we are supposed to have permission from Hdqtrs. to come here, but we didn’t have time to get it. Neither of us is dressed quite regulation so we spend most of our time dodging the A.P.M. around the Regent Palace, where we are staying.”60 Rex ran into Garside, his friend from Detling, as well as naval aviator James Caverly Newlin, Jr., whom he knew from Philadelphia.

The time at Chattis Hill was brief; Rex notes laconically that “this course is not bad.”61 C. G. Jeffords, in Observers and Navigators, describes how “Experimental work on speech transmission was under way in the UK by May 1915”; field trials in wireless telephony were undertaken in France in 1917. The Wireless Experimental Establishment at Biggin Hill started training Bristol Fighter and DH.4 and DH.9 crews in January 1918; in early April 1918 the training was “taken over by the newly established Wireless Telephony School which moved to Chattis Hill” around April 15, 1918.62 Such technology must have seemed a huge advance over the Morse code transmission and reception the second Oxford detachment members had spent many hours learning and practicing.

Rex’s time at Chattis Hill was punctuated by another trip to London for July 4, and he and Parrish were there once again when the course was over. On Thursday, July 11, 1918, Rex wrote that “We are waiting to hear from our Hdqtrs. And I think we will probably be sent to France Saturday.” In the meantime, he enjoyed London: “Saw Chu Chin Chow the other night and enjoyed it immensely. Had lunch today at the Overseas Officer’s Club (Automobile Club) with Parrish and his cousin Dr. [Clarence Couch] Elebash.” This was Rex’s last diary entry—“I think I will leave this book here in the suitcase I store at Cox’s because if I take it to France and then get scuppered or wounded they will go through my kit and pinch it.”

France

Rex’s name, along with Parrish’s, appears in a long list of men ordered to “proceed from London, England, to Issoudun, France, reporting upon arrival thereat to the Commanding Officer for duty in connection with aviation.”63 Issoudun, in the Loire region of central France, was the location of the American 3rd Aviation Instruction Center. There Rex would almost certainly have spent time training on American built DH-4s. His extant pilot’s flying log book ends with his last flight at Marske—perhaps he left the log book along with his diary at Cox & Co. in London—so there is no documentation of his flying in France.

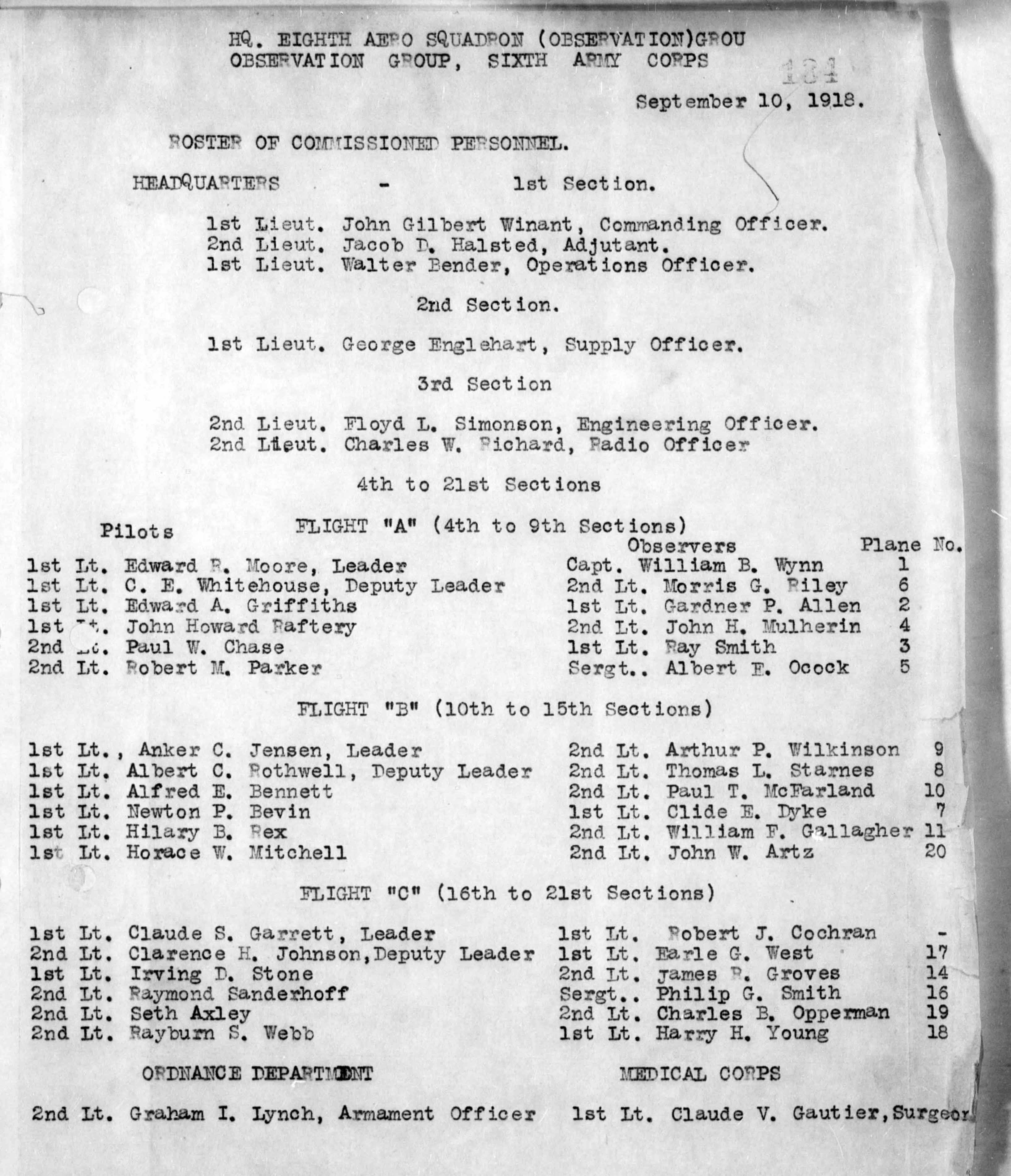

On August 19, 1918, Rex was assigned to the U.S. 8th Aero Squadron. His fellow second Oxford detachment members Edward Addison Griffiths, Anker Christian Jensen, Edward Russell Moore, and John Howard Raftery had been assigned the previous day, and Newton Philo Bevin soon followed.64

The 8th Aero was an observation squadron flying DH-4s; it had been at Amanty (about seventeen miles southwest of Toul) since the last day of July, attached to I Corps Air Service of the American First (and at that time only) Army. On August 31, 1918, as part of the planning for the St. Mihiel Offensive, the squadron was transferred to IV Corps and moved to Ourches-sur-Meuse, about eight miles due west of Toul, where IV Corps Air Service was based.65 The all too brief official history of the 8th Aero notes that “While at Amanty advantage was taken of our short distance from ‘the lines’ and a fortnight period of intensive training engaged in, which included flights over the enemy’s country.”66 This is substantiated by Jensen’s log book, which shows eight “test flights” in the last half of August; these continued during the first week at Ourches. It is reasonable to assume that Rex’s activity was similar.

There is a “Roster of Commissioned Personnel” dated September 10, 1918, that shows how the officers of the 8th Aero were divided up into flights. Rex, flying plane No. 11, was in B flight, which was led by Jenson. Rex’s observer was William Francis Gallagher, who, like Rex, was from Philadelphia; the two men may already have crossed paths, as both had been at Fort Niagara at the same time.67

The offensive to reduce the St. Mihiel salient began in the early hours of September 12, 1918. The 8th Aero was assigned to assist IV Corps’s 1st Division, which was at the westernmost part of the American line on the south front of the salient. The squadron C.O., John Gilbert Winant, reported that on the 12th and 13th planes of the 8th Aero “were in the air for thirty-six hours and thirty minutes . . . and twenty-four separate missions were accomplished.”68

The missions assigned were various: operations orders for the day specified that the 8th Aero, along with the 90th and the 135th, was to provide infantry contact, artillery counter attack, and artillery adjustment planes throughout the day on September 12, 1918 and to “operate in the areas occupied by the divisions to which they are assigned,”; additionally the 8th Aero was to “furnish one Artillery plane to work with the 8th Howitzer Battery. . . .”69 In other words, they were to fly over the front lines to gather and report information on the location of troops of the 1st Division as they advanced, while also working with them in aiming artillery. It had been hoped that the St. Mihiel attack could begin before the autumn rains, but this was not the case, and flying was undertaken in terrible weather with a low ceiling and strong winds.

Jensen’s log book shows him to have flown three missions, type(s) unspecified, on September 12, 1918. Rex’s activity with observer Gallagher was perhaps similar. The next day—the day Parrish reported to the 8th Aero—Rex and Gallagher set out on a mission; they did not return and were listed in the squadron history as missing in action.70

Rex’s name appeared on the official casualty list published October 15, 1918, where he is reported as missing in action; Gallagher was listed as missing in action on the preceding day’s casualty list.71 In November, Winant wrote to Gallagher’s family to report that both pilot and observer had been killed in action, but in December 1918 word was received from William Richards Castle, Jr., of the American Red Cross that Rex was a prisoner of war—this was, sadly, an error.72 In mid-February 1919, The Pennsylvania Gazette (the weekly magazine of the University of Pennsylvania) reported, accurately, that Rex had died of wounds in hospital at Bruville.73

The following month the same magazine published a letter from Graham Irwin Lynch, a University of Pennsylvania alumnus, with “The first authentic news concerning the death of Hilary B. Rex.”74 Lynch had served as armament officer with the 8th Aero from mid-August 1918 through early 1919.75 His account is worth citing in extenso:

On the morning of September 13th, about 6 o’clock, Rex left the field on a mission over the “Lines.” He and his observer were flying what is called the infantry contact plane, this being considered exceptionally dangerous work, due to the fact that it must be done at comparatively low altitude, thus placed under heavy machine gun fire from the ground. A heavy windstorm and occasional rains also added considerably to the peril of flying. Similar flying was done the day before, . . . but each time they left they were able to return safely and each time accomplished very successful missions. Even up until some time after they left the field on the morning of the 13th they wirelessed back valuable information.

But exactly what happened no one knows, except that they never came back. After it was realized that they never would return a searching party was sent out to gather all information possible, but their efforts met with but little success. A plane of the same type they had been flying was found in “No Man’s Land,” but it had been destroyed to such an extent that the serial number of the plane could not be thoroughly distinguished. It was believed, however, that this was their plane and it was reported as having been brought down in flames by an enemy aircraft. It was learned later that both pilot and observer were killed and had been buried by a company of infantry, but the exact location of their graves has never been found.

A few weeks before the signing of the armistice a note was dropped on a nearby airdrome by a German aviator, giving the names of American aviators who had been killed on the German side of the lines, and among them was the name of Lieutenant Rex.

A document dated October 11, 1918, from the records office of the Royal Saxon Ministry of War in Dresden verified Rex’s death—its contents were apparently transmitted to those in the U.S. by early 1919, assuming it is the source for the information in the February 14, 1919, Pennsylvania Gazette mentioned above.76 It states the Rex, shot in the abdomen, died on September 19, 1918, in a field hospital in Bruville and was buried in the cemetery there. American records indicate that observer Gallagher died on the day he & Rex were shot down, and was buried initially in a French civilian cemetery at Mars-la-Tour, which was then about six miles inside German lines.77

In May 1919 the bodies of both men were reinterred temporarily in the St. Mihiel American Cemetery at Thiaucourt and then, in August of 1922, they were given their final resting places at that same cemetery.78

mrsmcq May 4, 2023

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Rex’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Hilary Baker Rex. His place and date of death are taken from Todesnachweis des Rex. The photo is take from “Lieutenant Rex’s Grave Not Found.”

2 On the Rex family see Schutte, “George Rex (1682-1772) of Germantown, Pennsylvania”; and the account provided on pp. 1–2 of The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, “Collection 3003: Rex Family Papers.” And see documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 “Obituary: Walter E. Rex.”

4 Tatman, “Rex, Hilary Baker (d. WWI) Architect”; “Niagara ‘Rookies’ Start in Training.”

5 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

6 Rex, World War I Diary.

7 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for October 1, 1917. (Rex has misdated this entry; other sources make it clear that the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917.)

8 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for October 2, 1917.

9 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for October 3, 1917.

10 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for October 11, 1917.

11 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for October 21, 1917. For more extensive accounts of these events, see War Birds, entry for October 22, 1917, and the diaries of Barksdale, Deetjen, Grider, and Foss from around this time.

12 Rex, World War I Diary, has this move occurring on November 1, 1917; other documents make it clear that the cadets went to Grantham on November 3, 1917.

13 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for November 8, 1917.

14 Ludwig, diary entry for November 19, 1917.

15 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for November 8, 1917.

16 Rex, World War I Diary, entries for November 8 and 17, 1917.

17 Read, letter of November 10, 1917.

18 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for November 27, 1917.

19 See Foss’s list of “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers; and “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

20 On the planes used at 50, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 408.

21 “50 Squadron (home defense), location of B flight, December 1917-January 1918”

22 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for December 5, 1917.

23 Rex, World War I Diary, entries for December 16, 1917, and January 6, 1918.

24 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for January 13, 1918.

25 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for December 6, 1917.

26 H. A. Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 5, p. 104.

27 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for December 22, 1917, and passim. I believe Garside was at this time serving as an observer with No. 50 Squadron.

28 Rex. World War I Diary, entry for January 30, 1918.

29 Ibid.

30 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for February 28, 1918.

31 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for February 9, 1918.

32 Rex gives the plane’s serial number as “9993” in his pilot’s flying log book. Robertson, Military Aircraft Serials 1878–1987, indicates that both 9993 and B9993 were B.E.2c’s. Pilots were sometimes casual about providing letter prefixes, so Rex may have been flying either 9993 or B9993. Palmer’s and Benson’s logbook also record plane “9993″ as a B.E.2e rather than as a B.E.2c Possibly the plane they flew was built as a B.E2c but modified to be a B.E.2e. Information on Rex’s flying in what follows is taken from his pilot’s flying log book.

33 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for February 9, 1918. On MacIlwraith, see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for MacIlwraith.

34 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for February 9, 1918.

35 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for February 18, 1918.

36 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for February 21, 1918.

37 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for March 7, 1918.

38 Rex World War I Diary, entry for March 21, 1918; his pilot’s flying log book records his height test on March 17, 1918 in B4009, which he, in contrast to Robertson, British Military Aircraft Serials 1878–1987, designates a B.E.2d.

39 Rex. World War I Diary, entry for April 15, 1918.

40 Ibid.

41 Cablegram 874-S, dated April 8, 1918.

42 Cablegram 726-S.

43 Cablegram 955-R.

44 Cablegram 1303-R.

45 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for May 27, 1918. On Auld, see “Fashionable and Personal.”

46 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for May 27, 1918.

47 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for May 27, 1918.

48 Ibid.

49 Rex, Pilot’s flying log book.

50 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for June 6, 1918.

51 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

52 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for June 6, 1918.

53 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for June 6, 1918. Rex refers to May 30, 1918, as “Memorial day”; this designation was in common use at this time, although the name was not officially changed from Decoration Day to Memorial Day until much later.

54 Rex, Pilot’s flying log book, and Rex, World War I Diary, entry for June 6, 1918. ,

55 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for June 9, 1918.

56 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for June 16, 1918; Rex, R.F.C. Training Transfer Card..

57 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for June 16, 1918.

58 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for June 26, 1918.

59 Rex calculated his accumulated solo hours at Marske as totalling 7 hours and 35 minutes, but it appears he shortchanged himself. When I add up his individual flight times, I get 9.5 hours.

60 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for June 30, 1918.

61 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for July 3, 1918.

62 Jeffords, Observers and Navigators, p. 369.

63 [Biddle?], Special Orders No. 109.

64 See “8th Aero Squadron,” pp. 140–41.

65 See the brief “History of Eighth Aero Squadron (Observation)” on pp. 110–12 of “8th Aero squadron.

66 “History of Eighth Aero Squadron (Observation),” p. 110.

67 See Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for William Francis Gallagher.

68 “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 116; this is part of the “Report on Operations against the St. Mihiel Salient” submitted by Winant, which is also reproduced on pp. 689-91 of Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3. Unfortunately operations reports that might provide details of individual flights appear not to have been preserved; they are not, for example, in Gorrell C.14. Also unfortunately, the 8th Aero, unlike the 50th and 135th, did not find a dedicated chronicler.

69 Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3, p. 166.

70 “8th Aero Squadron,” pp. 142 and 148.

71 “Americans Killed and Wounded on the French Front,” (Oct 15, 1918, p. 8); “Americans Killed and Wounded on the French Front,” (October 14, 1918).

72 See newspaper clippings included in Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, record for Hilary B Rex. I should note that Castle’s cable, as cited in the December 5, 1918, newspaper clipping, states that Rex was shot down on September 12, 1918; this date appears in some subsequent reports.

73 “Six More on Roll of Honor.”

74 “Lieutenant Rex’s Grave Not Found.”

75 “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 140, and Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, record for Graham Irwin Lynch.

76 The document, “Todesnachseis Rex,” is among the papers in “Collection 3003: Rex Family Papers” at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

77 “Gallagher, William F.”

78 “Gallahger, William F.” and “Rex, Hilary B.”