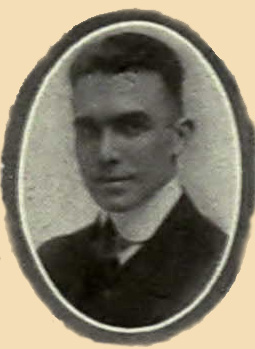

(Clinton, Iowa, July 7, 1890 – Clinton, Iowa, March 10, 1967). 1

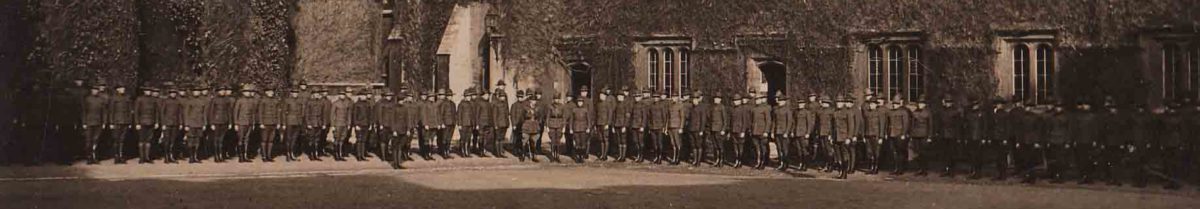

Oxford & Grantham ✯ 75 H.D. Squadron and After

Homer Ireland Smith, like many of his fellow second Oxford detachment members, had some German ancestry; I would guess that the family name was originally Schmidt. Smith’s great-great-grandfather, described as “born in Hesse-Darmstadt,” is said to have “come to this country as one of the soldiers in the employ of the English government during the Revolutionary war.” Captured by Continental troops, he changed his allegiance and became an American citizen, settling in Albany County in New York.2 His son, George Jacob Smith, spent his life in the German immigrant enclave of the same county, but in the next generation, John Henry Smith, Homer Ireland Smith’s grandfather, was more peripatetic, travelling and engaging in various trades in Connecticut and Illinois before coming to Iowa, where his plan to settle and perhaps farm was interrupted by a period as a volunteer in the Iowa infantry during the Civil War. After the war, he and his family lived in Clinton County, Iowa, where George Alfred Smith, Homer Ireland Smith’s father, was born. George Alfred Smith decided to study medicine and worked for a time with Dr. Alexander Baird Ireland of Camanche, Iowa, before entering medical school at Iowa State University. Not long after receiving his medical degree in 1881 George Alfred Smith married Marie Antoinette “Nettie” Ireland, a daughter of his erstwhile mentor, and a few years later he opened a practice in nearby Clinton. The Irelands can be traced back to a Calvert County, Maryland, family; Marie Antoinette Ireland’s grandfather moved to Tennessee and then Illinois; her M.D. father had come to Camanche in about 1852. Homer Ireland Smith had one sibling, a sister six years older than himself.3

Homer Ireland Smith attended schools in Clinton, graduating from high school there in 1909.4 He entered the University of Iowa in the fall of that year, initially to study applied science, but he went on to study law and received a law degree in 1916.5 He practiced in Clinton for just under a year before applying to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps.6 He was accepted and attended ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Illinois in Champaign, where, along with Raphael Sergius De Mitkiewicz, he was a sergeant in a crowd of privates; he graduated with the ground school class of September 1, 1917.7

Government flight training facilities in the U.S. were for the most part still under construction in the fall of 1917; offers from the Allies to give American cadets flying instruction in Europe were welcomed. It appeared that there were places available in Foggia, Italy, and men in the ground school classes of August 25 and September 1, 1917, were offered the option of signing up to do the next stage of their training there. Most of them, apparently including Smith, chose Italy. Shortly after graduating, Smith was among a number of ground school students ordered to Fort Wood in New York; from there he presumably went to Mineola on Long Island.8 On September 18, 1917, as Murton Llewellyn Campbell recalled, “we marched over to Garden City and took the Penna. to Long Island City, where we embarked on the Gen. Meigs, which took us down East River and up the Hudson to a dock. Then we walked aboard the Cunard liner, Carmania” —and set off for Europe as part of the 150-man strong “Italian detachment.”9

The Carmania made a brief stop at Halifax and there joined a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, setting out September 21, 1917. The men of the detachment travelled first class and had a good deal of leisure, apart from Italian lessons conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, assisted by violinist Albert Spalding. Towards the end of the voyage, as the convoy entered particularly dangerous waters, the men were assigned to submarine watch duty which was, fortunately, uneventful.

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, Smith and his fellow detachment members learned that they were not to go on to Italy but to remain in England and, even worse, as it seemed, to go through ground school all over again. They travelled by rail to Oxford and Oxford University where the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics was located. The “Italian detachment” became the “second Oxford detachment”—a first detachment of fifty American pilots in training had arrived at Oxford a month earlier.

Although initially dismayed at having to do another round of ground school, the men generally made their peace with the situation and in retrospect recognized the benefits of R.F.C. training. Their British instructors, unlike those in the U.S., had had war flying experience, and this added considerable interest to the course work. Since the men had already covered much of the material, they did not have to study especially hard, and they enjoyed Oxford hospitality and explored the town and surrounding countryside.

The men were eager to start flight training. More disappointment was in store for most of them. In early November, after four weeks at Oxford, they learned that the R.F.C. had places at No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford for twenty men from the detachment, but the others, including Smith, were sent on a machine gunnery course at Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire. As Parr Hooper, also sent to Grantham, remarked: “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”10

Murton Campbell described the men’s activities once they arrived at Grantham: “We are here . . . for four weeks, two on the Vickers [machine gun] and two on the Lewis. We are treated as officers and are called thus by the English officers. Eight of us in a tent with an orderly to take care of us. Nothing to do but go to the gun rooms and work on the Vickers all day long. We have from 9 to 1 P.M. with one or two hours out for field drill.”11

After the first two weeks the men learned that places had opened up for fifty of them at training squadrons. When the fortunate fifty were selected, there was some grumbling and charges of favoritism from the men who were not chosen. Geoffrey James Dwyer, in charge of American aviation cadets and flying training in England, had to intervene. Detachment member Fremont Cutler Foss was not present when Dwyer did this but noted in his diary that “H. I. Smith said Dwyer had made a speech: ‘These fifty men have been picked absolutely on merit alone either scholastic or military’.”

The approximately eighty men, including Smith, who remained at Grantham to do the Lewis machine gun course could only try once again to reconcile themselves to the uncertainties of army life. As at Oxford they took advantage of what free time they had to explore the town and its surroundings. They also began planning for Thanksgiving, which they celebrated with a football game and a traditional dinner. Many of the men at Stamford or other training sites came to Grantham to join in the festivities that day.

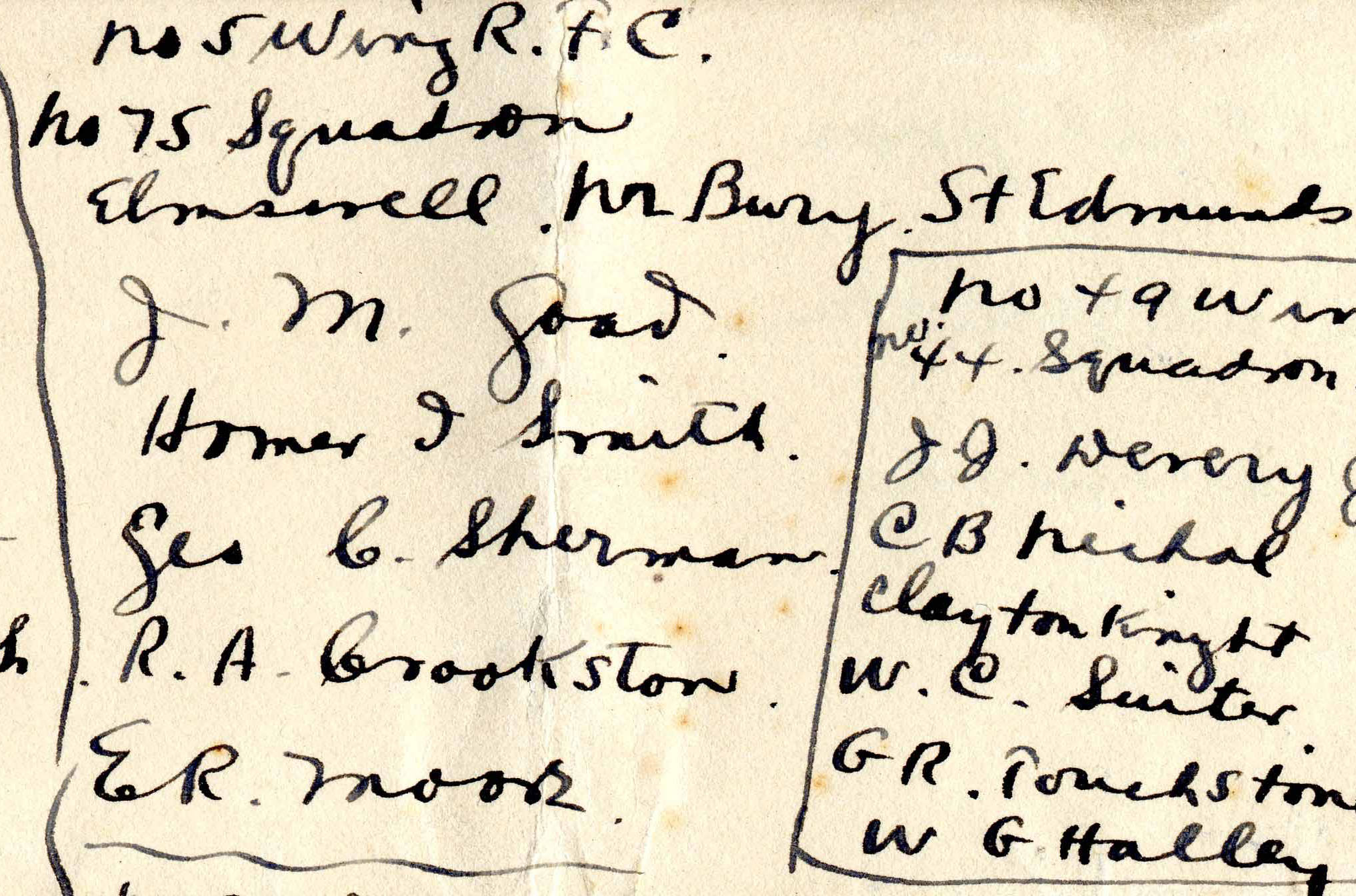

Finally, on December 3, 1917, the remaining men at Grantham were assigned to squadrons. Smith was one of five sent to No. 75 Home Defense Squadron, whose headquarters was near Elmswell in Suffolk. The other four, all from the same Illinois S.M.A. ground school class, were Ralf Andrews Crookston, John Marion Goad, Edward Russell Moore, and George Clark Sherman.12

As the name (Home Defense) indicates, No. 75 Squadron was not a training squadron but rather was tasked with intercepting Zeppelins and German Gotha bomber aircraft coming in over the East Anglian coast from the North Sea, usually at night. The five American pilots in training could thus not expect to receive priority. The squadron flew B.E.2s and B.E.12s, some of which could presumably be made dual control and used for instruction.13

The Americans were billeted in Stowmarket, a few miles southeast of Elmswell, at the Fox Hotel. Sherman wrote home that “A car calls for us every morning at 8:30 and brings us back every evening. The people at the hotel are mighty nice and do everything they can to make us comfortable.”14 On New Year’s eve, again according to Sherman, “The five of us Americans bought an eight-pound turkey for $5.00 and had the people at the hotel prepare it for us. We had a real feed—there was nothing left but the bones when we were through.”15

It appears that winter weather limited flying during much of December and early January (Jesse Frank Campbell, stationed for a time at nearby Thetford, recorded a number of days of high wind and rain in his diary). During the second week of January 1918, as Sherman wrote his mother, it had “been snowing and no chance to fly for three or four days so Smith . . . and I decided to spend a couple of days [in London] and see part of the city. We stayed at the Savoy Hotel and had a room that looked like it might have belonged to King George. We saw four shows—‘Chu Chin Chow,’ ‘Cheep,’ ‘Around the Map’ and ‘Here and There.’ They were very clever plays and much enjoyed by both of us. We met quite a number of our bunch that came over with us up to [sic] London.”16 Among those they saw was Jesse Campbell, who reported that “I was very glad to see [Sherman and Smith] again and exchange flying experiences. They are at a good place at Elmswell at a H.D. squadron (B.E.’s) but don’t get much flying.”17

In early 1918 there was apparently some bureaucratic confusion regarding Smith’s whereabouts. Towards the end of February a cablegram was dispatched from Washington to Pershing at American GHQ in France requesting “status Homer I Smith reported January 9th at Emswell [sic] flying field England.”18 The reply is dated March 3, 1918, and reports that “Homer I Smith cadet sergeant still in England. Last report January 19th two hours thirty five minutes flying.”

Sherman and Ed Moore, according to their letters home, began around this time (the latter part of January) to do a good deal more flying, and perhaps this was the case also for Smith and the others. Sherman, Moore, and Goad, in any case, had advanced sufficiently to be posted to intermediate squadrons in the last week of January; similar documentation is lacking for Smith and Crookston. There is, however, evidence that sometime before mid-May Smith was at No. 48 Training Squadron at Waddington in Lincolnshire.19

I find no further documentation of Smith’s (or Crookston’s) movements over the spring of 1918, but it appears that progress may have been frustratingly slow. While Sherman, Ed Moore, and Goad were all recommended for their commissions in February or March, the recommendations for Smith and Crookston were not forwarded until April 8, 1918.

A month previously Pershing, who had been made aware that many aviation cadets in Europe were unhappy that they had not yet been made first lieutenants, had sent a cablegram to Washington describing the situation of approximately 1400 men, some of whom had waited three months to start flying training, and some of whom, after five months, were still waiting and might have to wait another four: “All of those cadets would have been commissioned prior to this date if training facilities could have been provided. These conditions have produced profound discouragement among cadets.” To remedy this injustice, and to put the European cadets on an equal footing with their counterparts in the U.S., Pershing asked permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .” Washington approved the plan in a cablegram dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.” This explains why Pershing stipulated a status of “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying” in his April 8, 1918, cablegram recommending that Smith, along with thirty-eight other second Oxford detachment members, as well as many other cadets, be commissioned.

Washington took its time responding to Pershing’s April 8, 1918, cablegram. On April 30, 1918, Pershing wrote: “Request action taken on . . .” and lists cablegrams dated March 29 through April 8, 1918. The confirming cablegram from Washington is dated May 13, 1918.20 Smith was, finally, placed on active duty on May 28, 1918.21

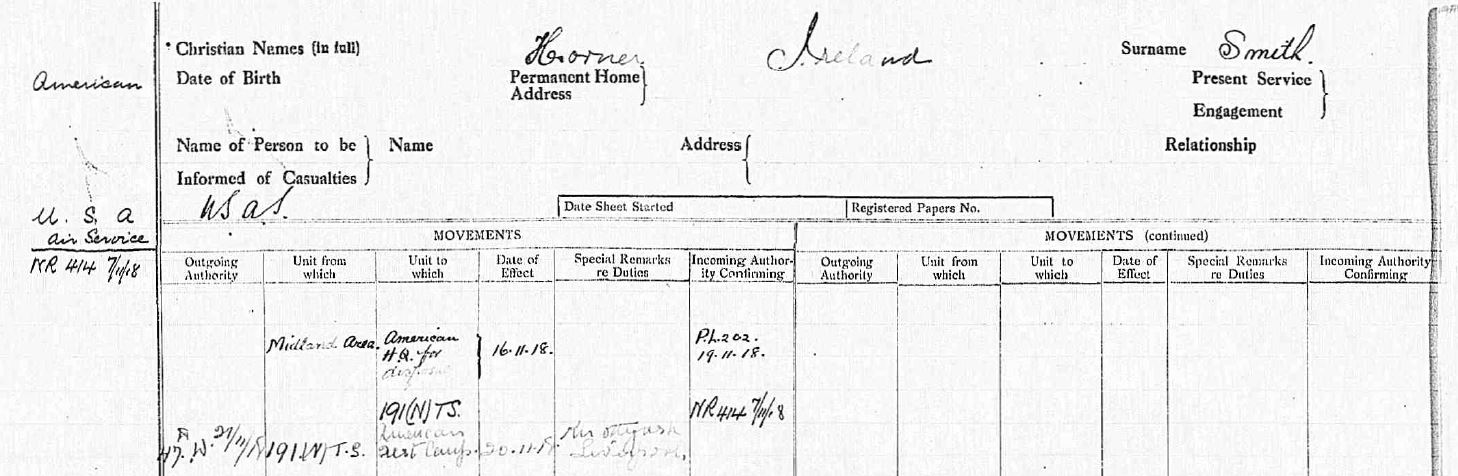

I find no direct documentation of Smith’s activities during the summer and autumn of 1918. A newspaper article from 1919 that indicates that Smith remained in England and trained for night flying. Both this article and a biography of Smith from 1931 suggest that he was actively engaged in home defense flying in England in 1918. This may be a misunderstanding based on his posting as a student to No. 75 HD Squadron, or it may be that Smith served with a home defense squadron after being commissioned.22 Smith’s brief R.A.F. service record has him at No. 191 Night Training Squadron in November 1918.23 No. 191 (N.) T.S. was “a non-operational night bombing training unit,” flying B.E.2s and DH.6s, and later F.E.2b’s.24 From July 1918 No. 191 was located in Upwood in Cambridgeshire, which had previously been used by No. 75 HD Squadron as a satellite field.25

According to his R.A.F. service record, Smith went from No. 191 to an American rest camp on November 20, 1918, and then to Liverpool. At Liverpool he, along with a number of other men from the second Oxford detachment, including his fellow sergeant from the Illinois S.M.A., De Mitkiewicz, boarded the Mauretania and set sail on November 25, 1918, arriving in New York on December 2, 1918.26 The Mauretania was greeted with much fanfare, as the first ship carrying American soldiers and aviators from Europe to arrive back in the U.S. after the war.

Smith returned to Clinton and resumed his law practice. In 1921 Albert Spalding, on a concert tour, stayed with Smith while in Clinton, and they were joined by George Sherman.27

mrmcq July 23, 2025

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Smith’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942, record for Homer Ireland Smith; I have not been able to locate his World War I draft card. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, Iowa, U.S., Death Records, 1880-1972, record for Homer Ireland Smith. The photo is taken from p. 107 of The Hawkeye of 1916.

2 The Biographical Record of Clinton County, Iowa, p. 423–24.

3 On the Smiths, see The Biographical Record of Clinton County, Iowa, pp. 380–84 and pp. 423–26. On the Irelands, see The United States Biographical Dictionary and Portrait Gallery of Eminent and Self Made Men: Iowa Volume, p. 299, and documents available at Ancestry.com.

4 Harlan, A Narrative History of the People of Iowa, vol. 4, p. 393.

5 The State University of Iowa, Iowa City, Calendar 1909-1910, p. 464; “Commencement 1916,” p. 14.

6 “To Serve in Aviation Corps.”

7 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917],” where for “Homer L. Smith” read “Homer I. Smith”; for his rank, see Krapf, “Muster Roll,” record for Homer I Smith.

8 A muster roll available at FamilySearch.org for the Illinois S.M.A. through October 31, 1917, notes Smith’s assignment to Fort Wood along with De Mitkiewicz and Laurence Kingsley Callahan. The opening diary entry in War Birds recounts how Callahan was originally bound for France, but was added to Grider’s group; it may be that Smith similarly was initially expecting to train in France. See Muster Roll of Det. Avia. Sec.

9 Murton Campbell, diary entry for September 18, 1917.

10 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

11 Murton Campbell, diary entry for November 5, 1917.

12 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

13 Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 416; Elmswell History Group, “RAF Elmswell WW1 Aerodrome.”

14 “George Sherman is Taking Rapid Steps in the Flying Game”; the Stowmarket hotel is identified in “Lieutenant Sherman is Anxious to Sail.”

15 “George Sherman is Taking Rapid Steps in the Flying Game.”

16 “George Sherman is Taking Rapid Steps in the Flying Game.”

17 Jesse Campbell, diary entry for January 9, 1918.

18 Cablegram 835-R.

19 “University Union in Europe.”

20 See cablegrams 726-S (March 13, 1918), 955-R (March 21, 1918), 874-S (April 8, 1918), 1029-S (April 30, 1918), and 1303-R (May 13, 1918).

21 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

22 “From Foot Ball to Battle Front”; Harlan, A Narrative History of the People of Iowa, vol. 4, p. 393.

23 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Horner [sic; sc. Homer] Ireland Smith.

24 The description of squadron is taken from comment by topgun1918 [pseud.] at “Bomber Harris’ AFC.” Information on planes available is taken from “RAF Upwood, Cambridgeshire”; see also the entry for No. 191 in Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units.

25 “RAF Upwood, Cambridgeshire.”

26 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for casual officers, Air Service, on Mauretania.

27 “Violinist is Entertained at Clinton Home.”