(Perryman, Maryland, May 14, 1893 – Ridgewood, New Jersey, February 4, 1964).1

Oxford & Grantham ✯ Flight training in England ✯ France and 206 Squadron R.A.F. ✯ Issoudun, Italy, and after

According to Hugh Douglas Stier’s granddaughter, Susan Patterson Buyer, who has done extensive and careful genealogical research: “The Stier family is first found in Frederick County, Maryland. The progenitors in Maryland were Jacob Stier and his wife Barbara Muellerin. Jacob and Barbara were probably German, either immigrants themselves or descendants of the German Palatine settlers of Frederick County”; Jacob Stier may have emigrated from Baden-Württemberg.2 Jacob and Barbara’s son, Henry Stier, and grandson, Hamilton W. Stier, were merchants in New Market, Frederick County, Maryland. In the next generation, Jay Hugh Stier left New Market for Baltimore to study medicine. After receiving his degree in 1886, he settled in Perryman in Harford County, Maryland, and opened a medical practice. In 1892 he married Lily Powell Patterson. Her family was originally from Baltimore, but recent generations had lived in Perryman, where she was born. The couple had two sons, of whom Hugh Douglas Stier was the older.

In 1907 Stier entered the preparatory school of St. John’s College in Annapolis; he was a private in Company A in the military department—I cannot tell whether this was obligatory or instead shows an early interest in a military career.3 In June 1908 Stier was awarded a prizefor “general excellence.”4 That fall he entered St. John’s College proper as a freshman to pursue an engineering course.5 He did not continue at Annapolis but instead enrolled at the Tome School, a preparatory school at Port Deposit, not far from Perryman, graduating in 1911.6 Stier almost immediately moved to Pittsburgh and began working as a salesman at Westinghouse. He subsequently worked for the Mercer Auto Company and then for the Railway & Industrial Engineering Company, both also in Pittsburgh.7 He was employed as a sales engineer at the latter company when he registered for the draft in June 1917.8

Stier was accepted into the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps by early July 1917 and was assigned to the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University in Columbus; the expectation was that he would go to France.9 However, around the time that Stiers’s ground school class graduated in late August, there were openings for flight training in Foggia, Italy—government flight training facilities in the U.S. existed at this time mostly on paper, and offers from the Allies to train American pilots were welcomed. Stier was one of eighteen men from this ground school class at O.S.U. who chose or were chosen to train in Italy, and he thus became one of the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment.”

After their graduation on August 25, 1917, the men had some free time during which many of them visited home. Then Stier and the others expecting to train in Italy gathered at Mineola on Long Island. On September 18, 1917, they were ferried to the west side of Manhattan to board the Carmania at a Cunard pier in the Hudson River. They sailed initially to Halifax; from there, on September 21, 1917, the Carmania set out as part of a convoy to cross the Atlantic. The men of the detachment travelled first class. They had plenty of leisure, apart from Italian lessons given by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them. They also, once the ship entered particularly dangerous waters close to the British Isles, were assigned to submarine watch duty, which was, fortunately, uneventful.

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, there was a change of plan. The men would not go on to Italy but remain in England and, even worse, as it seemed, go through ground school all over again. They travelled by rail to Oxford and Oxford University, where the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics was located. The “Italian detachment” became the “second Oxford detachment”—another detachment of fifty American pilots in training having arrived there a month earlier.

At Oxford the men spent their first night scattered among the various colleges; the next day they were divided into two groups. Sixty men were assigned to The Queen’s College and ninety, including Stier, to Christ Church, where they would remain for just over two weeks before being transferred with all the other Americans to Exeter College. During their time at Christ Church a photo was taken of the American and British cadets at the college; Stier can be identified in the fourth row from the bottom, second man from the right.

There was initially grumbling at having to repeat ground school, but the British instructors, unlike the ones in the U.S., had had war flying experience, and this added interest to the courses, which otherwise covered material familiar from U.S. ground schools (which were modeled on the R.F.C.’s). The men did not have to study hard, and they enjoyed exploring Oxford and its amenities and the surrounding countryside. On several occasions Stier and friends took advantage of days when it didn’t rain to take bike rides. William Thomas Clements, who had been in Stier’s ground school class, wrote in his diary on October 9, 1917, that “This afternoon was a beautiful one, so Stier and myself hired two bicycles and took a long ride between 2 o’clock and 4 o’clock. The roads around the country are very good and we had a very nice ride about three miles out. The country is filled with inns and they look very inviting. We stoped [sic] in one of these for awhile.” Two days later another O.S.U. classmate, Arthur Paul Supplee, joined them: “All three of us had an accident, almost breaking the machines. First on the program was my attempt to ride without my hands . . . Next, Stier ran into me and he was knocked over, tearing his trousers and also his knee. Next, some one ran into Supplee . . . We had a great deal of fun though.”10 On another occasion, as evidenced by a photo kept by John McGavock Grider, Stier joined Charles Edward Brown and Uel Thomas McCurry on a bike ride.

The men were eager to start flying training, but disappointment was in store for most of them. About four weeks after their arrival at Oxford, twenty men from the detachment were posted to No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford to begin flying training, but the others, including Stier, set out on November 3, 1917, for Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gunnery school. As Parr Hooper, also from Stier’s ground school class and also sent to Grantham, remarked: “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”11

The course was to be two weeks on the Vickers gun, and then two on the Lewis. Stier’s ground school classmate and soon very good friend, Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, took at least two photos at Grantham that include Stier. One is simply a group of men standing around a Vickers gun; the other shows Stier apparently aiming the gun.

After the first two weeks at Grantham, it was determined that there were places for fifty of the cadets at training squadrons, and Stier and Milnor were among those selected to go. The evening of November 18, 1917, there was a “‘Columbus’ farewell party at the George” for Stier and Milnor, with ground school classmates Charles Carvel Fleet, Clarence Bernard Maloney, Roland Hammond Ritter, and Guy Samuel King Wheeler, all four of whom would stay at Grantham for two more weeks.12

Stier and Milnor, along with Henry Bradley Frost, Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, and Joseph Ralph Sandford, were posted to Tadcaster, seventy miles north of Grantham. Setting out the morning of November 19, 1917, they made the first part of the train journey north with ten men who had been assigned to Doncaster. From Doncaster the five journeyed on to Selby, where Stier and Milnor took in the Abbey with its Washington window before boarding the train to Tadcaster. There “We were met by a lorry, which brought us and our luggage out to the Aerodrome, about two and a half miles from the station . . . Capt. Lloyd, the adjutant of the 14th Training Squadron, the one we were posted to, showed us our rooms. They were in a hut something like the ones at Grantham, but were real rooms. Doug and I had a room to-gether and Hamilton, Frost (who is in charge) and Sandford had one in the next hut.”13

The next day, a squadron holiday, the men looked around the aerodrome and filled out paperwork. Milnor and Stier were assigned to C flight under George Robert Graham Smeddle. The planes used for instruction were Maurice Farman S.11s, known as “Rumpties.” These were “pusher” planes, i.e., ones with the propeller behind the cockpit. Rumpties had been flown at the front early in the war but were now used in training. Milnor noted that they “are rather hard to fly but are said to give great confidence when left behind and we go on regular machines.” It was understood that “We will have to do between 4 and 6, possibly more, hours dual control and 2 hours solo with ten landings when we will then go to an advanced squadron.” It turned out they also had to do yet more ground work and pass various exams; poor weather also limited flying time. Nonetheless, Milnor went up on the 22nd, and on November 26, 1917, Stier “went for his first flight at 7:00 and was unimpressed.”

As at Oxford and Grantham, there were opportunities to explore the area. The town of Tadcaster held little attraction, but nearby Leeds was worth visiting. On one occasion there “Doug and I proceeded to get pretty happy on real highballs”; a few days later they celebrated Thanksgiving at The Queens Hotel in Leeds. They also bicycled one evening over to Boston Spa for a dance.

Milnor made his first solo flight on December 11, 1917, and noted that day in his diary that Stier was scheduled to do the same. Despite poor weather, including snow, over the next few days, both of them had completed the elementary squadron requirements on December 18, 1917, and were “now both ready to leave.” The next evening they learned that “Doug, Ham[ilton] and I were to go to the 23rd Wing, South Carlton near Lincoln for disposal.” A tender (truck) took them into York the next morning, where they caught a train to Lincoln, and then another tender to South Carlton. “We were assigned to No. 45 T.S., after signing many papers. Were then given a room large enough for the three of us, no 1. Hut 13. It is just as comfortable as at Tad.”

No. 45 was a pool squadron, where men awaited further assignment. Once again there was ground work: classes in the mornings, and then they were expected to make themselves useful at the hangars in the afternoon. This was still the state of affairs when Murton Llewellyn Campbell paid a brief visit to South Carlton on December 28, 1917 on his way to his next posting: “Had to wait two hours at the Lincoln station waiting for a lorry to take me out to S.C. Went in to see the fellows. There were Doug [Charles William Harold Douglass], Goody [Weston Whitney Goodnow], Sties [sic], Hamilton, Milnor, [Lynn Lemuel] Stratton, [Bradley Cleaver] Lawton and [Leonard Joseph] Desson, all posted to the 45 Pool Squadron.”

Finally, on the last day of the year, Milnor learned that “Doug, Ham and I had been transferred to 61 T.S. for flying. Great Excitement!!!” 61 T.S. was also at South Carlton, so they did not need to change quarters. That same day “Doug and Ham went up in the afternoon in an Avro and were awfully discouraged”—Milnor does not elaborate. Just three days later “Doug and Ham both went solo and are very confident.” On January 6, 1918, according to Milnor, Stier had a forced landing—evidently with no serious damage to himself or his machine. On January 14, 1918, Stier made a cross-country flight to Spittlegate (near Grantham), thus fulfilling one of the main requirements for graduation from this level of training. Just under two weeks later, he had evidently completed the other requirements (a set number of hours solo, flying at high altitude, flying an operational plane, etc.), for, on January 27, 1918, Milnor writes that he “went into Lincoln with Doug who is on 4 days graduation leave.”

No. 206 Squadron, commanded by Colin Temple MacLaren, was part of the R.A.F.’s 11th Wing, which was flying on the British 2nd Army front in northern France and Flanders; their planes were DH.9s. John Stephen Blanford, an observer with 206 who arrived not long before Stier, describes the squadron’s area of responsibility: “our sector of operations, which was in fact the 2nd Army Front, ran from Houthulst Forest, 10 miles north of Ypres down as far as Nieppe Forest, 20 miles SW of [Ypres]—roughly 30 miles in all.” He notes that the war on the ground at this period was relatively quiet on this front. “In the air, however, there was still no lack of activity, and all 11 Wing squadrons were in the air whenever the weather permitted flying.” Enemy aircraft seldom entered Allied territory, so “all our encounters with the enemy took place over their territory.”22 The squadron was tasked with tactical bombing, reconnaissance, escort work, and photography.

Leach, in a letter written shortly after he joined the squadron, described how “We go over the lines in formations of five to twelve machines, and do our work. . . . We fly from 15,000 to 20,000 feet now—four miles high. We have to take oxygen with us, for we are up from two to four hours at a time.”23 Blanford writes of an occasion when he and his pilot “had recourse to our primitive oxygen apparatus. This involved sucking the stuff through a rubber tube that always tasted foul. I doubt if this really did us much good, as we were both feeling rather groggy by the time we began to lose height after re-crossing the lines.”24 Another pilot, Edward Trevor Evans, noted that the squadron was “situated a long way behind the lines—about 25 miles—so that to get our height (say 13,000 feet) and to get to the lines alone will take us an hour and a half.”25 On a more homey note, second Oxford detachment member Clayton Knight, who joined the squadron at Alquines in mid-August, wrote: “The collection of tents and huts where we live and eat straggle down the side of a slope looking over an immense valley with rolling hills patched everywhere with fields of oats and wheat, clover and freshly ploughed land.”26

It has been stated by American historians of American pilots with the R.A.F. that R.A.F. regulations required new pilots to take two to three weeks to familiarize themselves with their squadron, their planes, and the territory before crossing the lines.27 At 206, however, Blanford, Leach, and Schlotzhauer all made their first operational flights well before fourteen days had elapsed, perhaps because the regulation was not in force there, or perhaps because the squadron was short on men.28 In the absence of Stier’s log book, the date of his first operational flight is not known for certain, but it was probably June 12, 1918, just six days after his arrival at 206.

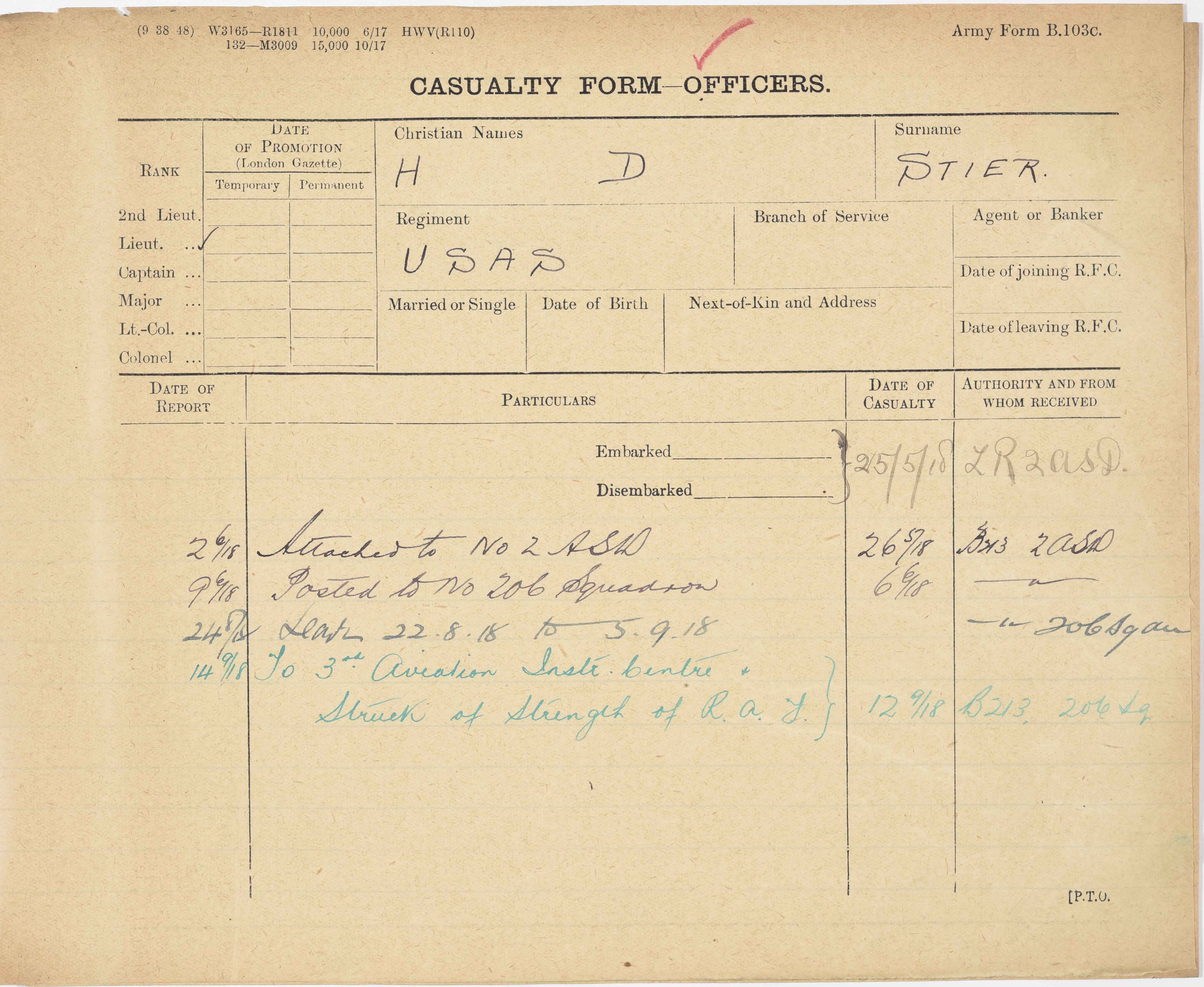

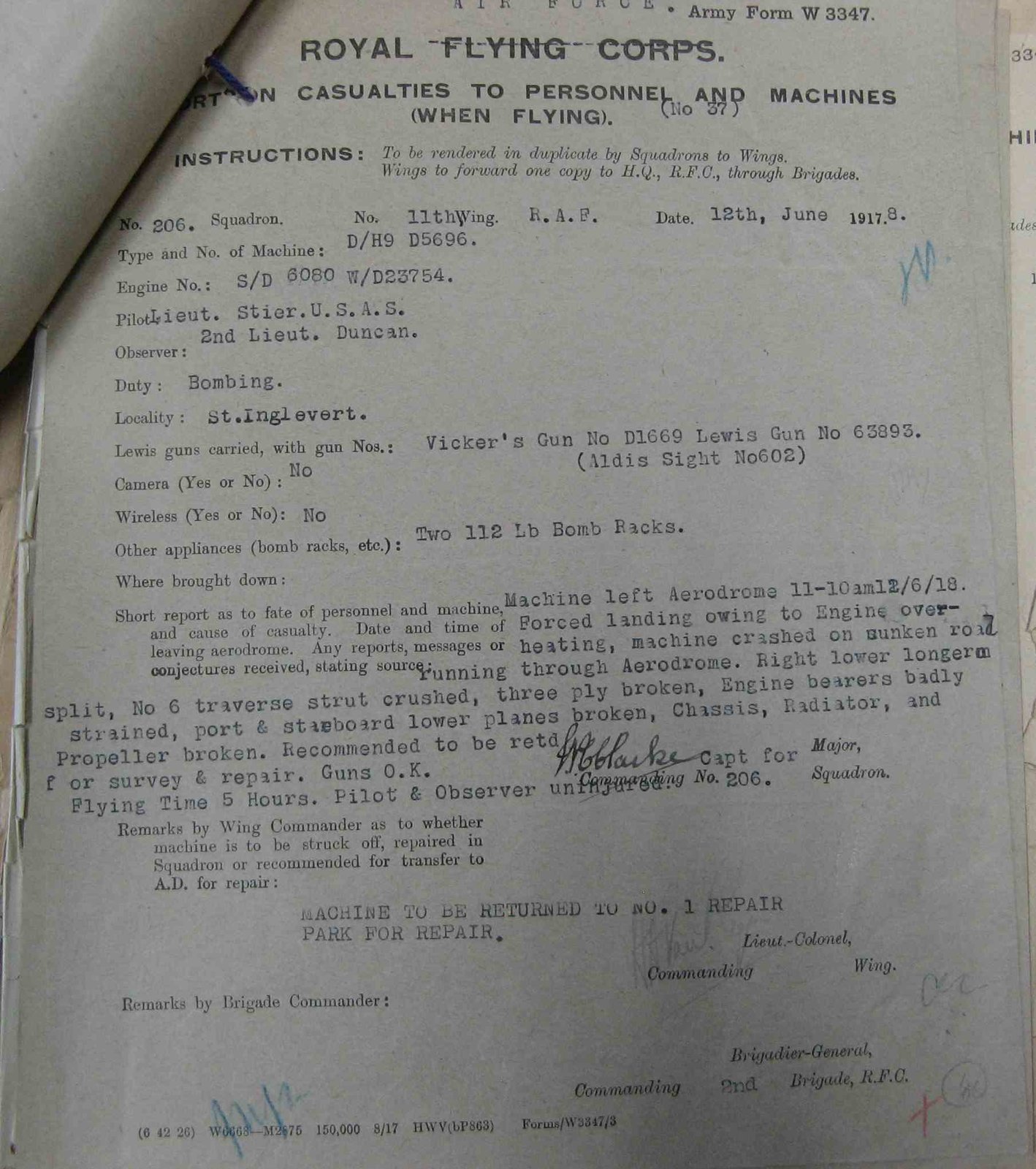

A casualty report for DH.9 D5696 indicates that on that day, Stier, with observer William Gardiner Duncan, set out on a bombing mission just after 11 in the morning.29 They made a “Forced landing owing to Engine overheating, machine crashed on sunken road running through Aerodrome. . . . Pilot and Observer uninjured.”30 This, apparently Stier’s first and, as far as I can tell, only crash, occurred at St. Inglevert, about fourteen miles northwest of Alquines.

The casualty report, unfortunately, does not provide the time of the forced landing, and it is thus unclear at what point in the mission it occurred—as they were setting out (possibly flying towards the coast to gain height) or on their return. The mission they were flying was probably the one to bomb Cortrai on which Leach was badly wounded, when he and his machine were successfully flown back to the aerodrome by his observer, James Chapman.

Leach was invalided out, so his experience provides no further guidance, but Schlotzhauer’s log book indicates that he flew on 10 days during the remainder of the month of June. It is likely that Stier’s experience was similar and that he took part in bombing raids on, for example, Courtrai (Kortrijk) and Roulers (Roeselare) in Flanders, and Halluin in France, as well as in reconnaissance and line patrols. At some point, possibly immediately after Leach was invalided out, Leach’s observer, James Chapman, became Stier’s.31 Near the end of June, another man from the second Oxford detachment, Galloway Grinnell Cheston, joined the squadron, and he was apparently assigned to B flight with Stier.32 (R.A.F. squadrons typically had three flights, each composed of six men or teams and their planes.)

Blanford notes that there were a number of days in July when flying was not feasible, and there is a five day, presumably weather-related, gap in Schlotzhauer’s log book between a raid on Roulers on July 7 and the next on July 13, 1918. Around the middle of the month, according to Blanford, “there was a marked increase in enemy fighter activity . . . the famous ‘Circus’, originally led by von Richthofen and now by Hermann Goering, was paying our sector a visit.”33 Nevertheless, a perusal of this period in Henshaw’s The Sky Their Battlefield II shows 206 flying largely unscathed until July 25, 1918. That morning DH.9 C6121, piloted by Francis Turretin Heron with observer Charles Joseph Byrne was shot down during a bombing mission; both men perished.

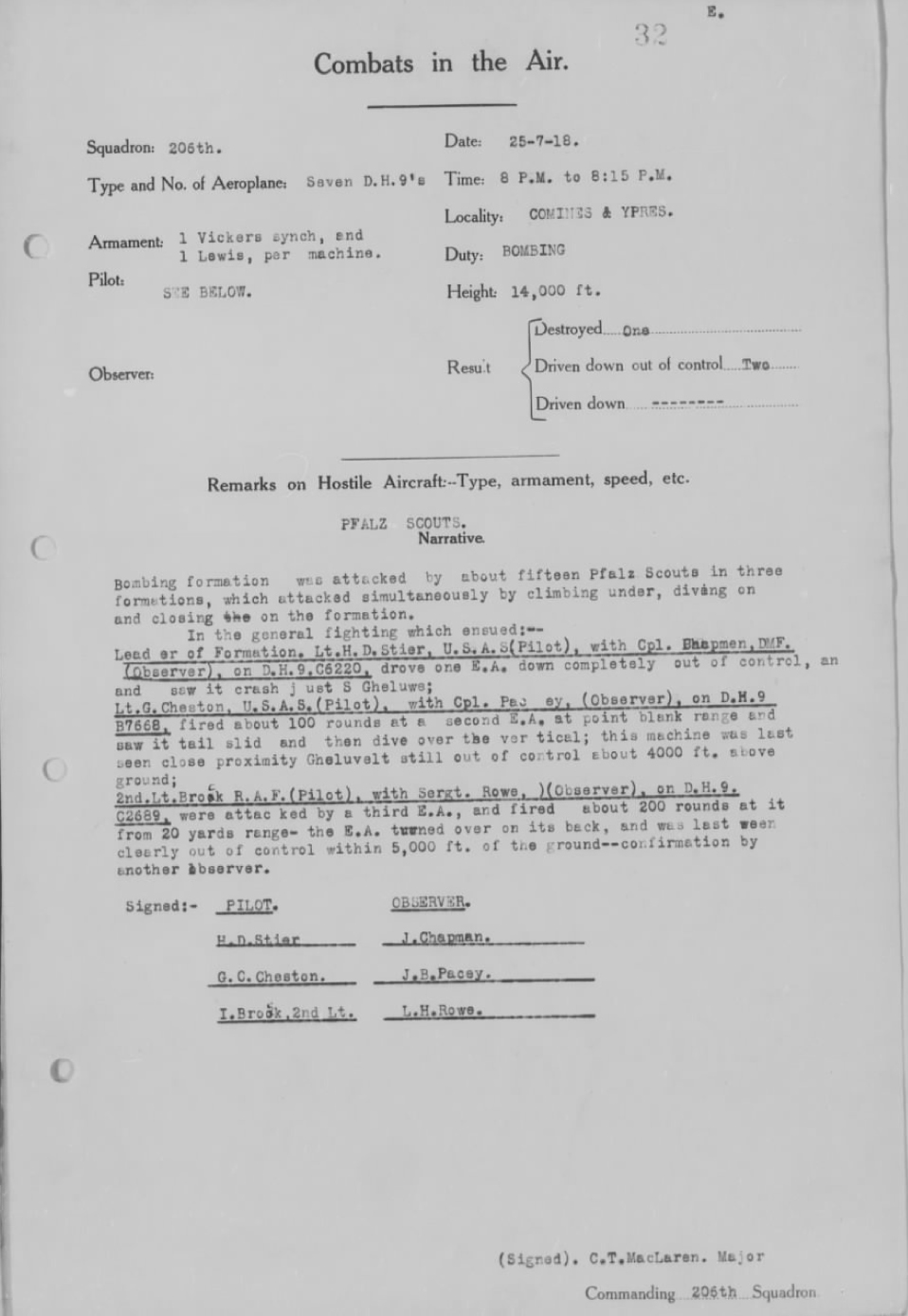

The evening of that same day, Stier, flying DH.9 C6220 with observer Chapman, led a formation that included Cheston on a bombing mission—I find no record of their objective. Flying at 14,000 feet in the vicinity of Ypres and Comines at about 8:00 p.m., probably on their return journey, the DH.9s “were attacked by about fifteen Pfalz Scouts in three formations, which attacked simultaneously by climbing under, diving on and closing on the formation.”34 Stier and Chapman “drove one E.A. down completely out of control, and saw it crash just s[outh of] Geluwe.”35 Cheston with observer Joseph Woodley Pacey and Frederick Albert Brock with observer Leslie Holman Rowe accounted for two further enemy planes driven down out of control.

Four days later, on July 29, 1918, Stier, Schlotzhauer, and Cheston were members of a seven plane formation that took off from Alquines at 5:35 p.m. to attack “the railway siding at the southwest outskirts of” Cortrai.36 At about 7 p.m., just before reaching the target, they were attacked by as many as thirty Fokkers and Pfalz planes; they dropped their bombs and “made a bee-line for Ypres.”37 Stier, Schlotzhauer, and four others made it back to the aerodrome; Cheston and his observer were shot down and killed.

As the British and French prepared for the Battle of Amiens, which was to open on August 8, 1918, R.A.F. activity on the Second Army front was to be artificially increased to disguise the build up further south. In the event, poor weather the first few days of August limited German reconnaissance opportunities and also meant that No. 206 was largely prevented from flying.38

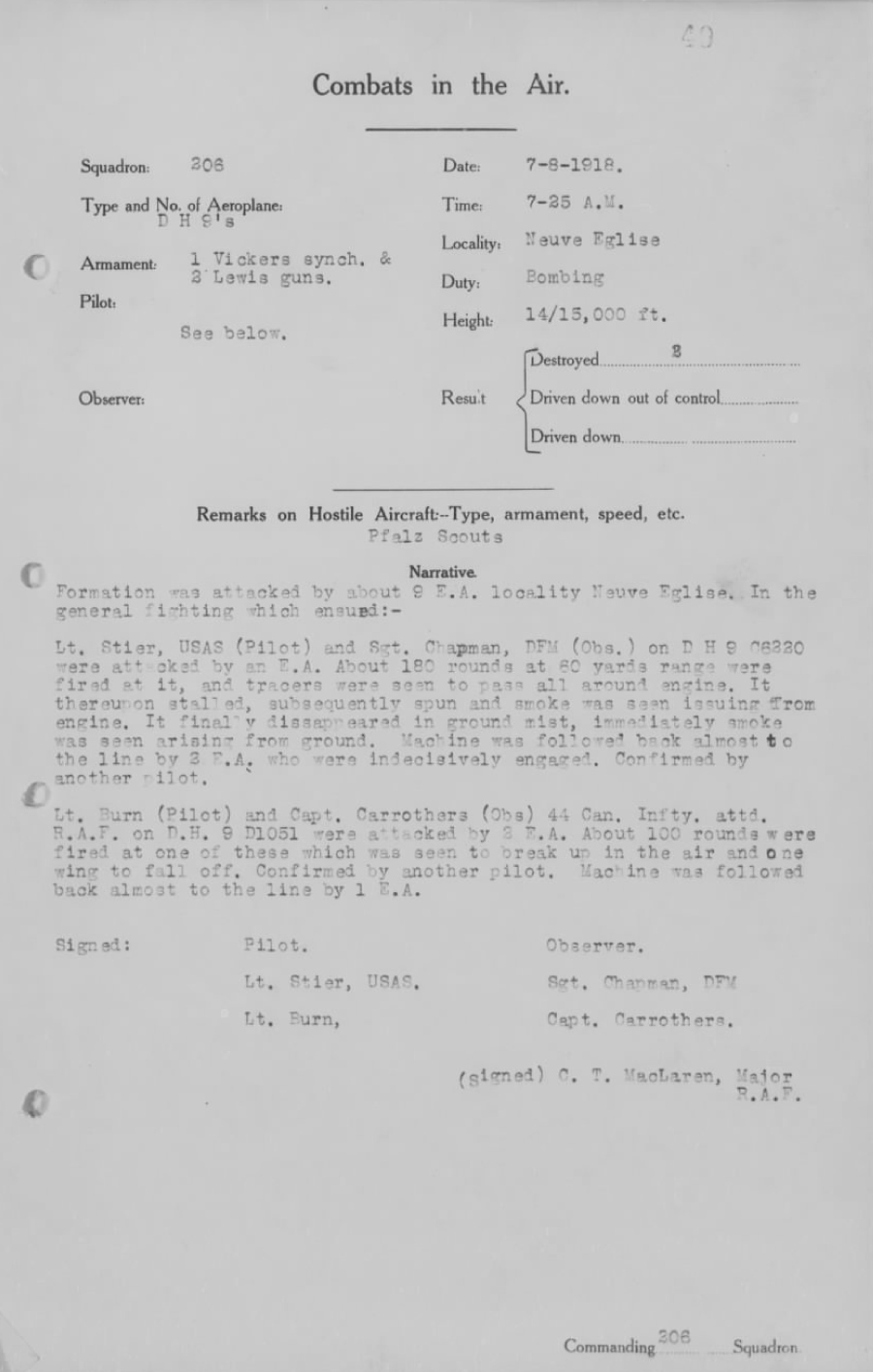

On August 7, 1918, weather having improved somewhat, Stier and Chapman, again flying DH.9 C6220, took part in an early morning bombing mission along with, among others, Eldon Abraham Burn and observer William Alexander Carrothers in D1051.39 Looking at the entries for 206 Squadron in Henshaw’s The Sky Their Battlefield II, it appears that Frederick Albert Brock with observer Charles Hulbert Cullimore in C6289 and John Frederick Spencer Percival with Leslie Irton Lowthian in D5816 flew this mission as well; they took off from Alquines at 5:30 a.m. Once again, there is no record of the objective, but it may well have been Cortrai. At 7:25, when they were flying at 14 – 15,000 feet over Neuve-Eglise (Nieuwkerke) and probably, but not certainly, returning from having dropped their bombs, the “Formation was attacked by about 9 E.A.”40 When one of these Pfalz Scouts targeted Stier and Chapman, “About 180 rounds at 60 yards range were fired at it. . . . It thereupon stalled, subsequently spun and smoke was seen issuing from the engine.”41 Stier and Chapman’s plane was “followed to the line by 2 E.A. who were indecisively engaged.”42 Chapman and Carrothers were also able to shoot down one of the attacking planes. Brock and Cullimore, however, were shot down and did not survive; Percival and Lowthian’s plane was badly shot up, but they managed to reach the lines and crash land a few miles from Alquines.43

Not long after this engagement, Milnor, working at American Aviation HQ at 35 Eaton Square in London, wrote in his diary: “Had a letter from Doug Stier. He now has two Huns officially which is fine for a D.H.9”—i.e., for a plane not intended as a fighter plane.44 Stier’s further activity in August can only be surmised from that of Schlotzhauer and Blanford, who each flew 10 missions before going on leave August 16, 1918.45 Stier himself was on leave from August 22 through September 5, 1918.46

From a chance remark in Milnor’s diary, it appears Stier spent the first part of his leave in Eastbourne, a resort town on England’s south coast47. Milnor, meanwhile was on leave in Eastport near Liverpool. Back in London on September 2, 1918, Milnor was able to meet up with Stier: “Met him at 7:30 at the Piccadilly and we went to Murray’s and sat and talked till closing time.” The next day, “Doug came in the office and Geoff [Dwyer] wired through to France recommending that he be sent to Italy as a navigation officer.” Stier was presumably as upset as Milnor when official word came through to Aviation HQ on September 4, 1918, that Hamilton, their friend from training at Tadcaster and South Carlton, was missing.

Stier’s leave was up the next day: “Doug left at 11:00 for Lympne [on England’s south coast] where he is to get a machine and fly it direct to his Squadron. So he won’t have the rotten train journey.”48

On September 10, 1918, Paul Stuart Winslow, a member of the first Oxford detachment and assigned to No. 56 R.A.F., noted in his diary that “orders came through for thirteen of us,” including Stier, “to report to No. 3 Instructional Center at Issoudun.” The next evening at No. 206 Squadron there was a farewell dinner for Stier and Schlotzhauer. In a letter dated September 12, 1918, Evans (mentioned briefly above) wrote that “Last night we had quite a jolly evening owing to the fact that two topping American officers who have been with our Squadron some time are leaving us today to join one of their own squadrons—just formed.”49 As so often, there was confusion about next postings.

Of Stier’s service at 206, squadron commander MacLaren wrote: “[Stier] has taken part in 25 bomb raids, 5 long reconnaissances, 1 line patrol, 2 photo reconnaissances, has taken 384 photographs and has done excellent work while with his present squadron.”50

Writing on September 13, 1918, Winslow described how he and the others posted to Issoudun “Reported to Headquarters and were told to come back tomorrow. We are worried about what is going to happen to us. When we reported to Major [Thomas George] Lamphier [sic; sc. Lanphier], we were told that we were ordered here by mistake, and they did not know what to do with us, but would wire Tours and let us know tomorrow.”51

Eventually, towards the end of September 1918, Schlotzhauer arrived at the U.S. 91st Aero Squadron; there is, unfortunately, no such definite information about Stier, other than that he was at some point assigned to Foggia in Italy. His name appears on a list dated November 8, 1918, of officers there; I would guess he had been there since mid to late September.52 There is no indication of what role he played, but it is most likely he was a navigation instructor at the 8th Aviation Instruction Center at Foggia. La Guardia, who had taught Stier and his fellow cadets Italian while they were on the Carmania, had gone on from Liverpool to Foggia with a detachment of cadets and served for a time as second in command at the 8th A.I.C. It is possible that Stier and La Guardia were able to renew their acquaintance, but also that La Guardia was no longer there when Stier arrived.

Among the documents included in the first volume of the series on aviation training in Gorrell’s History of the American Expeditionary Forces Air Service, 1917–1919 is a “List of Officers Who Have Demonstrated Exceptional Ability.” It is undated, but was probably compiled soon after the end of the war. Stier’s name appears in the list of day bombardment pilots, with the annotation: “British trained. Excellent officer for O[fficer] I[n] C[harge] Navigation or Field. Photo Officer.”53

Stier was able to return to the U.S. comparatively soon after the Armistice. He sailed on the U.S.S. Martha Washington, departing Brest December 9, 1918, and arriving at Newport News, Virginia, on December 19, 1918.54 Not long after his return, news came that the Italian government had shown its appreciation for the men who served at the 8th A.I.C. at Foggia by authorizing them to wear the Italian Service Ribbon.55

For a time after the war Stier lived in Chicago and Atlanta, working in sales for manufacturing firms. In the 1930s he and his family settled in Ridgewood, New Jersey, and there he was able to keep up his friendship with Milnor.56

mrsmcq August 19, 2025

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Stier’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Hugh Douglas Stier. His place and date of death are taken from “Stier.” The photo is a detail from a group photo of Stier’s ground school class.

2 “Family: Stier, Jacob Sr. / Mullerin, Margaret Barbara,” at Buyer, Buyer, Stier and Related Families. Other information about the Stier family is also from Buyer’s site, supplemented by documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 St. Clair, Rat-Tat 1908, pp. 84 & 110.

4 St. John’s College, Catalogue of St. John’s College Annapolis Maryland for the Academic Year, 1908–1909 and Prospectus 1909–1910, p. 94.

5 Ibid., p. 16.

6 “Twenty-Two Graduates of Tome.”

7 See The National Archives (UK), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Hugh Douglas Stier, which includes Stier’s employment history.

8 Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for

9 “Pittsburg Men to Become U.S. Airmen.”

10 Clements, diary, October 11, 1917.

11 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

12 Milnor, diary, November 18, 1917. Subsequent quotations and information related to Stier’s time in England, unless otherwise noted, are from Milnor’s diary. The date is generally evident from the context.

13 I have not been able to identify Capt. Lloyd.

14 See Stier’s R.A.F. service record, cited above.

15 Ibid.

16 See Stier’s service record, cited above, and Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

17 This assumption is based on the experience of other second Oxford detachment members at Marske; see, in particular, Leach’s log book.

18 See their respective log books.

19 Milnor, diary, April 27, 1918.

20 Harold Hatch Gile was a member of the first Oxford detachment; he was assigned to No. 49 Squadron R.A.F.

21 See their respective casualty forms: “Lieut. H A Schlotzhauer U. S. A. S.,” “Lieut. J W Leach USAS,” and “Lieut. H D Stier USAS.”

22 Quotations are taken from Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 147. Blanford’s two-part article is one of the few extensive sources of information on No. 206 Squadron in World War I; valuable as it is, it does contain some errors.. For a succinct summary of 206’s activities in the early part of 1918 (prior to Blanford’s arrival), see Bruce, “The De Havilland D.H.9,” pt. 1, p. 388. The chapters on 206 during this period in Gunn’s Naught Escapes Us, rely heavily on Blanford as well as a few other source documents in the 206 Squadron Archives. Document AIR 27/1221 in The National Archives (UK) includes a mere three and a half page summary of operations during the period.

23 “Lieut. Warren Leach, Tuscaloasa [sic] Birdman, Tells in Letter of Air Fighting.”

24 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 148.

25 “‘With Fondest Love, Trev.’,” letter of August 26, 1918.

26 Knight’s letter is reproduced in “How Bombs are Dropped from Planes on Enemy.”

27 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 117, provides a version of this regulation, as do Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 35.

28 Information on Leach’s and Schlotzhauer’s flying is taken from their respective pilot’s flying log books.

29 My digital copy of this record comes from a post by Nieuport11 at The Great War Forum. The original will be in The National Archives (United Kingdom), Reports on aeroplane and personnel casualties.

30 Ibid .

31 Chapman appears as Stier’s observer on Stier’s two combat reports; see Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F., pp. 32 and 49.

32 See Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 154; pt. 2, p. 21.

33 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 150.

34 “Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F.,” p. 32.

35 Ibid. Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 151, has perhaps been misled by the wording of the relevant R.A.F. communiqué and gives the date of this combat as July 22, 1918. Cf. Communiqué No. 17 in Great Britain, Royal Air Force, Royal Air Force Communiqués 1918.

36 From Schlotzhauer’s narrative in Cheston, World War One Burial File, p. 58.

37 Ibid. Entries for this day in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, suggest the attack occurred closer to 7:30.

38 See Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, entry for August 6, 1918; and Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 151.

39 Information on this mission is taken from the combat report by Stier et al. on p. 49 of “Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F.” and from the entries for this day in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, where “J Lowthian” is perhaps a mistranscription of “L [I] Lowthian.”

40 “Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F.,” p. 49.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II.

44 Milnor, diary entry for August 12, 1918.

45 See Schlotzhauer’s log book and Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 151.

46 See his casualty form, “Lieut. H D Stier USAS”

47 Milnor, diary, September 2, 1918.

48 Milnor, diary, September 5, 1918.

49 “‘With Fondest Love, Trev.’.”

50 Quoted in the entry for Stier on p. 49 (242) of Munsell, “Air Service History.”

51 “Attached to No. 56,” entry for September 13, 1918.

52 See “Roster U.S. Army Air Service in Italy.”

53 “List of Officers Who Have Demonstrated Exceptional Ability,” p. 302.

54 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service Arriving and Departing Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for H. D. Stier.

55 “Ribbons for 48 Aviators.”

56 From obituaries posted at Stier’s page at Buyer, Buyer, Stier and Related Families.