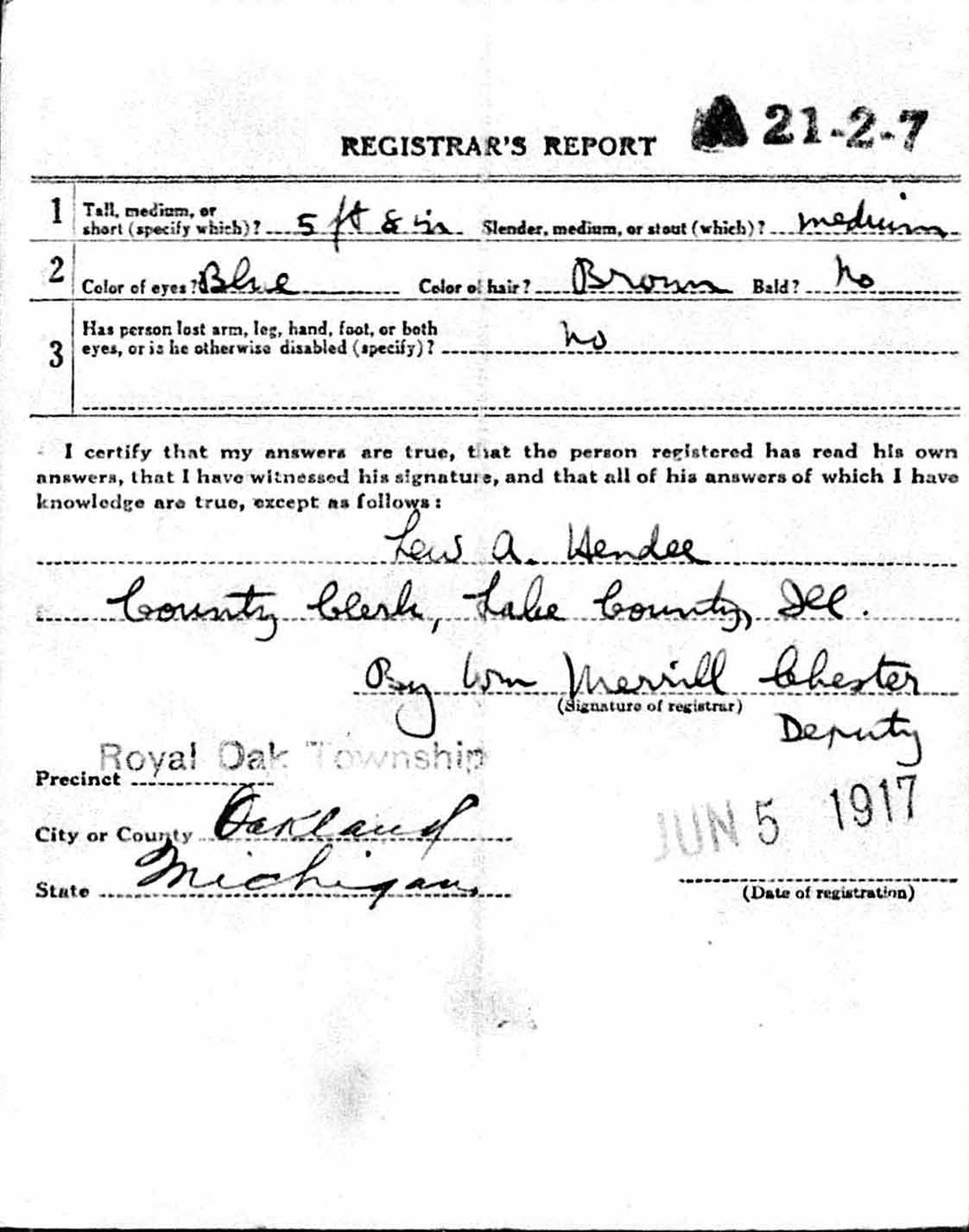

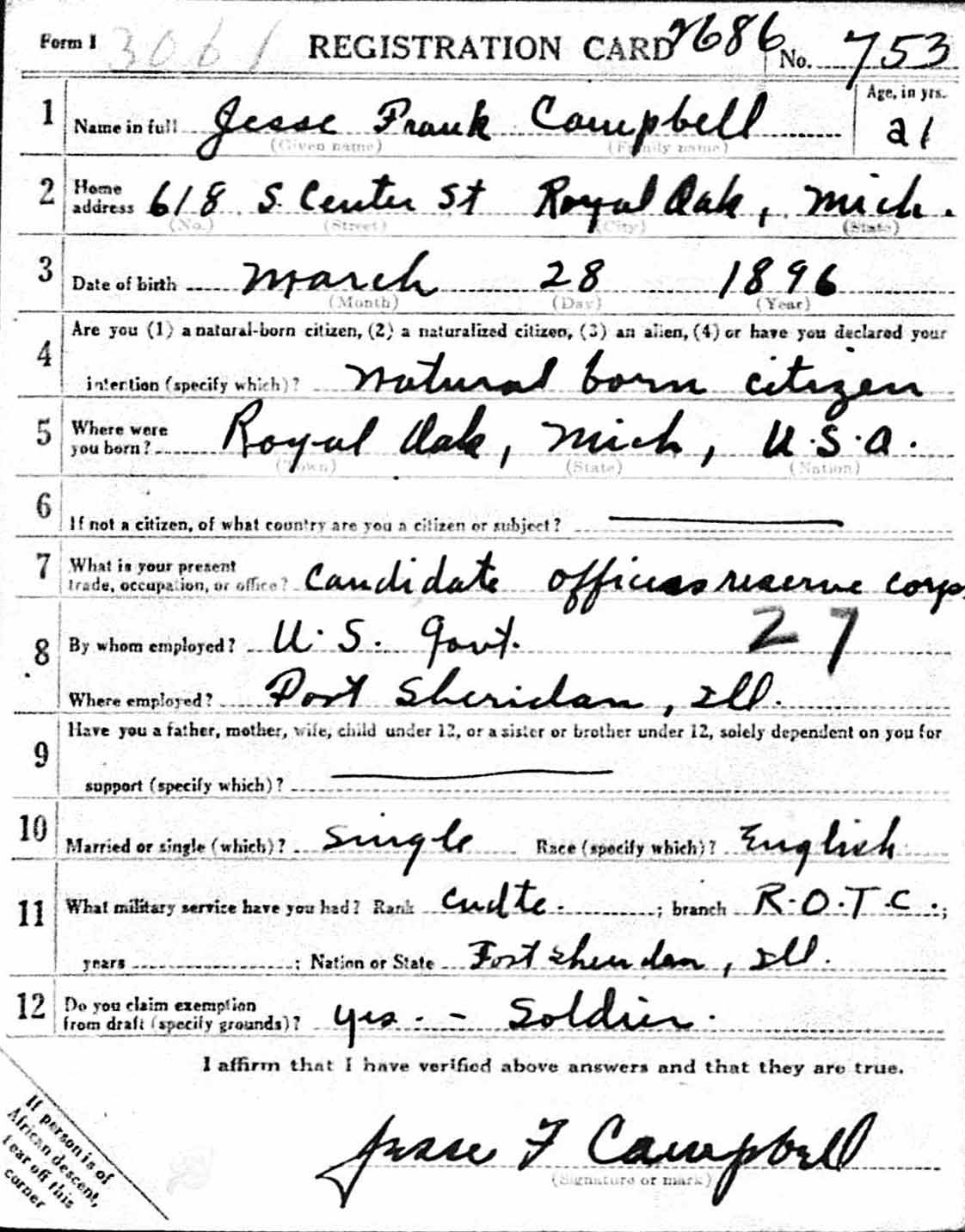

(Royal Oak, Michigan, March 28, 1896 – Detroit, Michigan, February 9, 1939).1

Oxford and Grantham ✯ Thetford ✯ London Colney ✯ Marske & Dover ✯ The 17thAero Squadron, Petite Synthe ✯ Auxi-le-Château ✯ Sombrin ✯ On leave, Toul, home

Campbell’s father was a farmer in Royal Oak, northwest of Detroit, who went on to become a building contractor. Jesse was the oldest child and only boy; he had five sisters.2 He attended Albion College in south central Michigan, but interrupted his studies in 1917. When he registered for the draft, he was in the R.O.T.C. at Fort Sheridan in Illinois. He attended ground school at the University of Illinois, graduating September 1, 1917.3

Along with most of the men from his ground school class of about thirty, Campbell chose or was chosen to go to Italy for flying training and thus sailed with the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” to England on the Carmania. Like a number of other men in the detachment, Campbell marked this new chapter in his life by starting to write a diary. It opens on September 18, 1917: “Left Mineola at 7:30 and boarded the Carmania at 11:30.”4 The ship sailed first to Halifax, where it joined a convoy for safety during the Atlantic crossing; the convoy left Halifax on September 21, 1917. “At 4:00 we lifted anchor and again we were off. Leaving harbor was an impressive scene. The shores were lined with cheering crowds and every ship gave us lusty hurrahs as we passed. As we passed the Admirals [sic] flag ship ‘To the Colors’ was played followed by the ‘Star Spangled Banner.’ It made me proud to be from old U.S.A. There are fourteen ship [sic] in our convoy, one being a battle cruiser to protect against German raiders.”5 The crossing was uneventful, but anxiety increased as they entered the Irish Sea where there was greater danger from mines as well as from submarines. “Lights appeared on shore at 9pm” on October 1, 1917, “and I slept better knowing I would not have far to swim if we were sunk.”

Oxford and Grantham

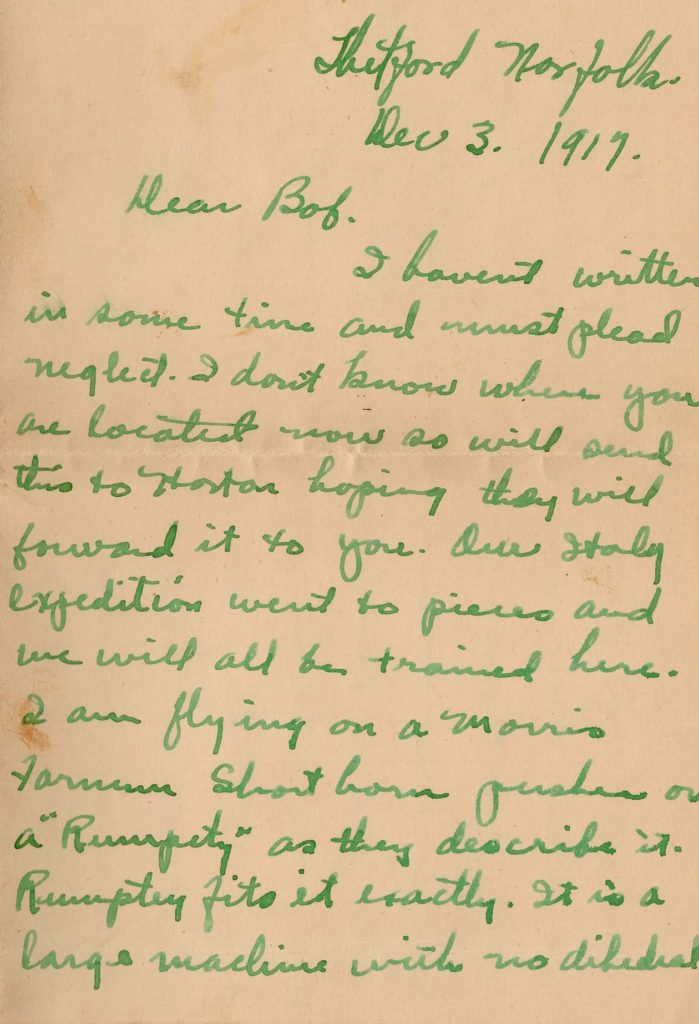

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men learned that “our Italy expedition went to pieces” (as Campbell wrote to his Albion classmate, Bob Crosthwaite) and they “were to stay in England for instruction.”6

They travelled by rail to Oxford. Campbell spent his first night in England in Brasenose College; the next night he was among the sixty cadets (as they were now called) assigned to Queen’s College (the other ninety were at Christ Church). His roommates on the fourth floor were Edward Russell Moore and George Clark Sherman, and he continued to room with them when all the American cadets were relocated to Exeter College later in the month. Still on an upper floor, he wrote: “I am getting used to rapid changes of elevation climbing up and down stairs.”7 On Monday, October 8, 1917, Campbell and his fellow detachment members started ground school over again, this time at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. Some of the men grumbled, but Campbell was not one of them. “They cover about the same things which I had at Champaign but take them up quite differently. Next to being at flying school there is no where in this country I would rather be than here. It is a fine school and I am going to like it very much.” “It is a real treat to study under these officers who have seen service and know what they are talking about. . . . One of the members of the Laffatte [sic] Esquadrille was here today.”8 Campbell encountered men he knew from ground school who were now in the first Oxford detachment: “Reed Landis and a bunch of others who left for France from Champaign before I did are here also. Those who actually reached France are no better off but are driving nails building hangars so far.”9 Being in England Campbell likened to “stepping back 50 years. . . . Thatched roof houses and old fireplaces that we used to read about in fiction are here in fact. No electric cars, few automobiles, hand pushed milk carts, and bicycles, everyone rides a bicycle.”10

On November 3, 1917, most of the detachment, including Campbell, went to Grantham in Lincolnshire for machine gun training at Harrowby Camp. Here they enjoyed a slight elevation in status: “We are officers in treatment if not in fact,” and they no longer had to wear the white bands on their R.F.C. caps which at Oxford had marked them as cadets. “We have officers mess and quarters and a batman to wait on us, make bed, shine shoes and belts and call us ‘sir’.”11 Classes began November 5, 1917, “and it looks as though I might know something about the Vickers [machine gun] before long if they keep on the way they have started. Every screw and knob is accounted for.” Ten days later, Campbell learned that he and four others (Eugene Hoy Barksdale, Austin Finley Morrison, Alexander Miguel Roberts, and Glenn Dickenson Wicks) had been posted, at last, to “the 25th training squadron at Thetford. I hate to leave Sherman and Ed Moore but I suppose it must come sooner or later anyway.”12 He took his final exam on the Vickers on November 17, 1917, and “I was among the 10 highest in the squadron getting 152 out of a possible 160 points.”

Thetford

At Thetford (“smaller than Grantham and seems just as dud”) there were “only 5 of us at this squadron and with decent weather we would get a lot of flying. Winter weather is very uncertain and it may take six weeks to get through. . . . This is quite a cosmopolitan squadron; there are Canadians, Australians, Scotch, South and East Africans besides the English and Americans. . . .”13 Because of bad weather, Campbell had to wait nearly three weeks before flying; the monotony of classes (“Same old stuff. I am beginning to get fed up with it”) was broken by a Thanksgiving trip to London. Finally, on December 8, 1918, he “had a fine ride today. Lt. Whalley and I went on a cross country trip. . . .”14 His first flights were on Maurice Farmans (“Rumptys”): “They say that once you have learned to fly one . . . you can fly anything. The course here consists of 4 hrs dual and 4 hrs solo and 15 landings. . . . Flying is a wonderful game and I quite enjoy it. It is quite a sight to see the earth spread out beneath you and you go blissfully along until you hit an air pocket which wakes you up rather suddenly.”15

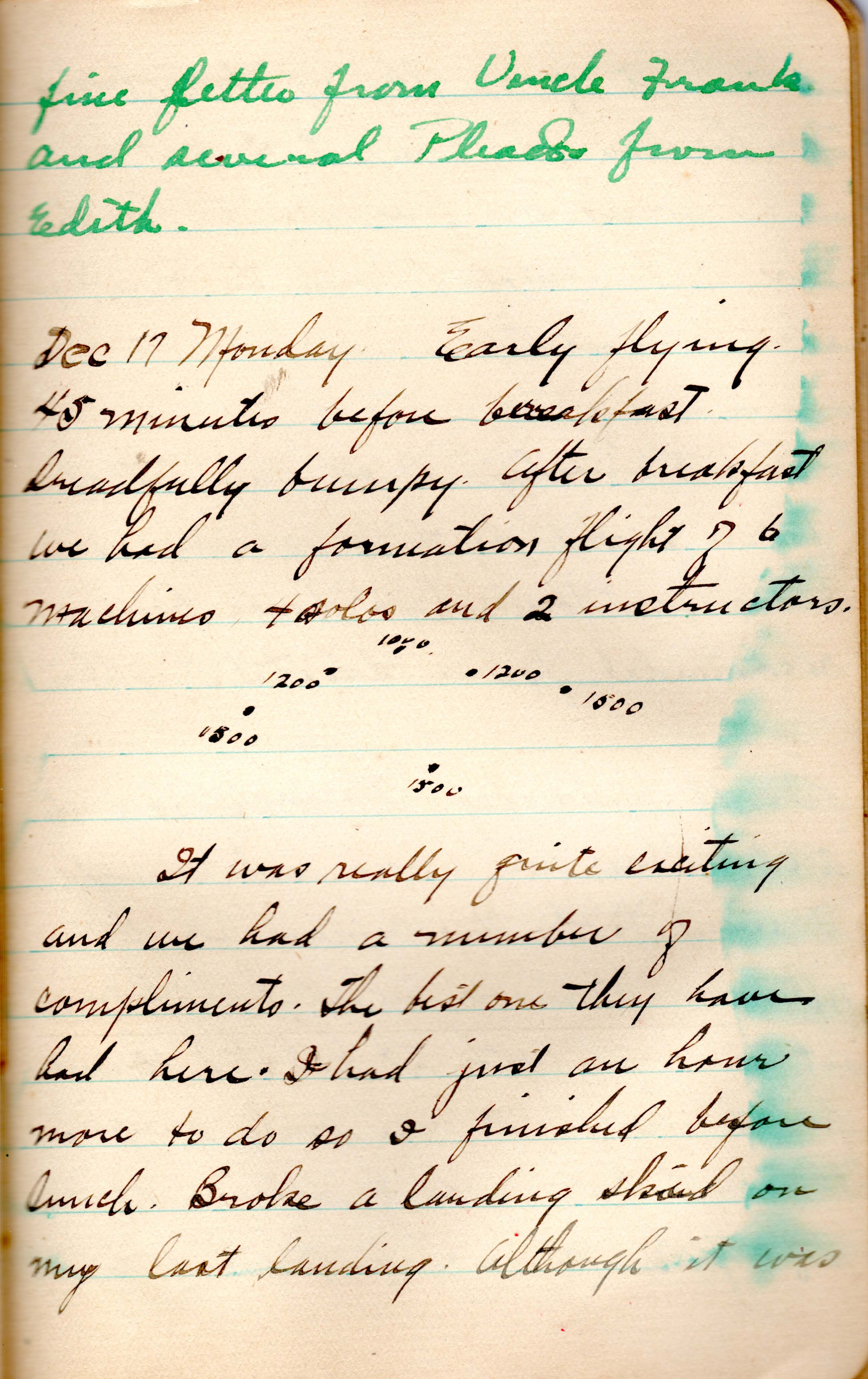

Less than a week later, on December 13, 1917, Campbell made his first solo flight, and by the 17th he had completed his course on “Rumptys” (despite having broken a landing skid on his last landing) and was preparing to move on. He got a brief leave in Norwich, where he and Morrison had a cordial dinner with Lt. Col. George Haddon Bower of the Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) and his wife, who was the sister of the celebrated soprano, Mary Garden.16

London Colney

Despite having been recommended at Thetford for Bristol Fighters, Campbell, on December 21, 1917, left No. 25 Training Squadron for London-Colney and No. 74 T.S. where the planes he would train on were Avros, Sopwith Pups, and S.E.5s.17 He spent Christmas in London, and when he returned to London-Colney found that “the rest of the fellows had arrived from Thetford and the mess is beginning to look quite American. There are about 15 of us here now.”18 Laurence Kingsley Callahan, Marvin Kent Curtis, Clarence Horne Fry, and John McGavock Grider had been in another training squadron at Thetford and were now also, along with Barksdale, Morrison, Roberts, Wicks, and Campbell, at London-Colney, as were Guy Maynard Baldwin, Charles Edward Brown, John Hurtman Fulford, Parr Hooper, Thomas John Herbert, Francis Kinlock Read, and perhaps Linn Humphrey Forster, Robert Alexander Anderson, and others. A number of them, perhaps including Campbell, were billeted at the Red Lion in Radlett.19

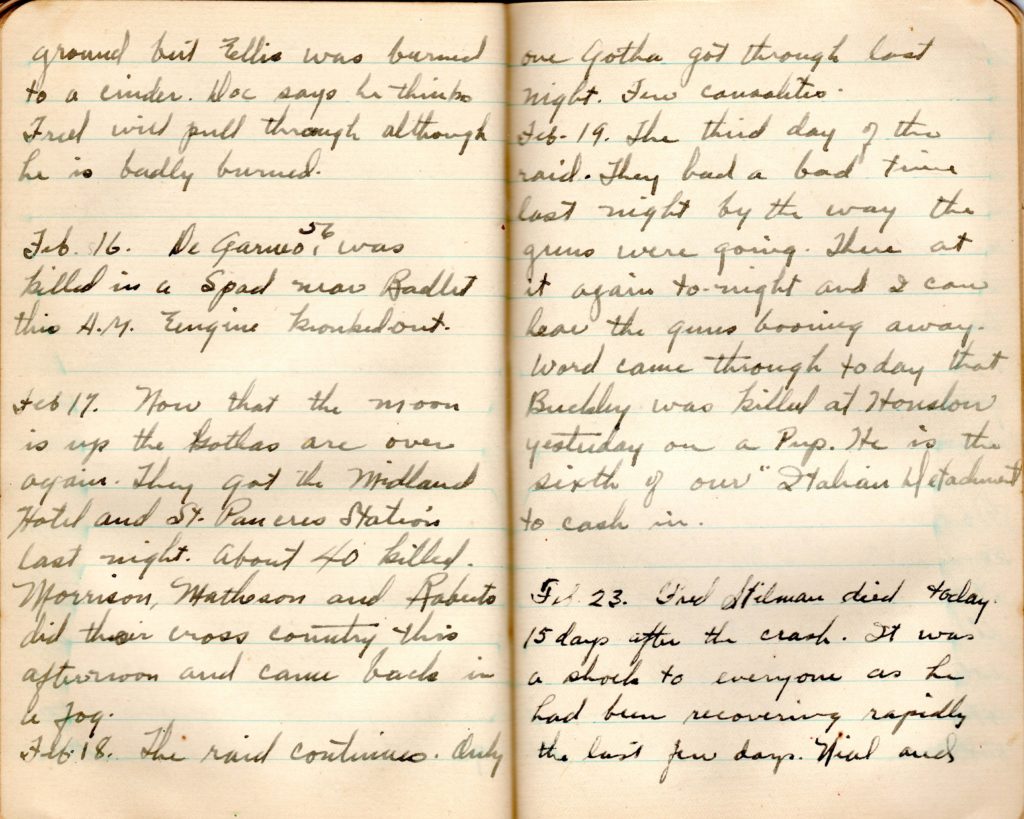

The dangers inherent in flight training began to be borne in upon Campbell. He had noted in his diary a crash involving Roberts and instructor Gordon Shergold Creed at Thetford, as well as the one that injured Stanley Gordon Minchin.20 On December 29, 1917, at London-Colney he wrote that “Today was a bad day on the Aerodrome, 4 bad crashes although no one was fatally injured.” About a week later he learned of Joseph Hiserodt Sharpe’s fatal crash at Waddington—“poor fellow the first one of our bunch to go. I can hardly believe it.”21 A day later he went to London to see Sherman and Smith (presumably Homer Ireland Smith), returning the next day with James Ira Thomas “Taffy” Jones and John Harding Greathead, both of 74 Squadron. “As we were on parade this afternoon we saw a S.E.5 catch fire at 1000 feet. It was Jack Greathead a South African. He made a fine attempt to get down but when about 20 feet up crashed into the ground. The petrol tank caught alight and the flames shot up 40 feet. Before anyone could reach the machine it was in cinders. The poor fellow probably died instanteously [sic]. Not ten minutes before it happened I was talking to him. It is awful to have one snatched away so quickly and in such a manner.” Campbell only wrote two entries in his diary over the next month or so, both recording crashes: the mid-air collision of Joseph Frederick Stillman of the second Oxford detachment with Canadian Douglas Quirk Ellis on February 8, 1918, and, on February 16, 1918, the crash that killed Lindley Haines DeGarmo of the first Oxford detachment. Campbell resumed writing in his diary almost daily, and on February 19, 1918, noted that “Buckley [sic; sc. Bulkley] was killed at Hounslow yesterday on a Pup. He is the sixth of our ‘Italian Detachment’ to cash in,” and four days later, that Stillman had died.

Despite this litany of tragedies, perhaps in defiance of it, Campbell showed himself an intrepid flyer. On February 24, 1918, he recorded that it was his day to go solo on Avros. “I have had enough dual so that I was perfectly confident. I caused a little sensation by looping on my first solo. I had told the fellows I was going to so I had to. Made a good one too.” And a few days later: “I looped, spun, and Immilmaned [sic] and found the Avro would dive at 120 without the wings dropping off. I’ll have to put her to 130 now and see what happens.”22

On the last day of February Campbell and Fry did their required cross country flight: “Since I had been to Northolt before, I was elected leader. We ran into a snow storm after leaving Northolt and got lost, landed at Brooklyns [sic; sc. Brooklands?] and after getting our bearings arrived safely at Hounslow.” He noted that same day that “All the Avros and Pups are being sent away” and the next day that “The Squadron has begun to mobilize. 20 SE’s are in now and each has been assigned to a pilot. Major [A. S.] Dore, our new C.O. arrived today and promises to be a good fellow.”23 This remark suggests that Campbell, Curtis, and other pilots in training at 74 T.S. believed or hoped they would remain with the squadron. However, on March 5, 1918, they moved across the field at London Colney to No. 56 T.S., as No. 74 had ceased its existence as a training squadron and become operational. At 56, which still had Avros and Pups, Campbell continued his training, and towards the end of March “graduated on Pups,” qualifying for four days leave, which he spent in Salisbury.24 Not long afterwards, the recommendation for his commission was forwarded to Washington; it was among the many whose approval, for no apparent reason, was long delayed; the confirming cable is dated May 13, 1918.25

Marske and Dover

Campbell finished on Spads on May 12, 1918; a few days later, “Curtis Wicks and myself started for school of aerial gunnery at Marske” in north Yorkshire where they would train on S.E.5s.26 He, like others who trained at Marske, probably assumed he would go to France to fly S.E.5s, but it was decided that some of the men—including himself, Curtis, Wicks, and Forster—were to be switched to a different service machine; on June 19, 1918, he “started for Dover to fly Camels.”27 A few days later, at No. 65 Training Squadron there, he wrote “Took my first flip on a Camel. Not so bad as I had heard they were.”28 Camels had a justly deserved reputation for being difficult to learn to fly, as the torque of their rotary engine could pull them quickly into an uncontrollable spin when flown by an inexperienced pilot. After a week’s sick leave to recover from flu at the end of June, Campbell spent the month of July training at Dover.

With the 17th Aero at Petite Synthe

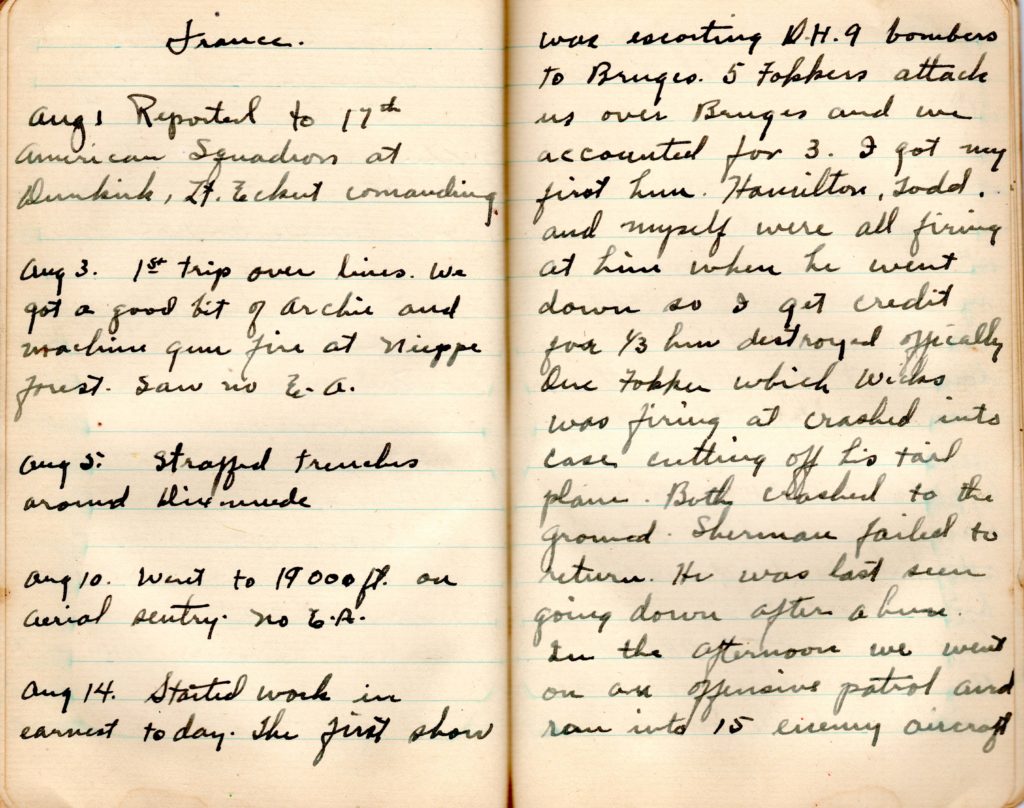

On July 29, 1918, Campbell wrote that “Wicks and myself started overseas.” They crossed to Boulogne the next day, and on the 31st “Started for Dunkirk to 17th American Squadron ‘Camels’.” The 17th Aero Squadron had been at Petite Synthe near Dunkirk since the end of June, and a number of second Oxford men had already been assigned to it.29 The 17th, along with the 148th, was American in personnel, but stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. Assigned to Lloyd Andrews Hamilton’s C Flight, Campbell made his first venture over the lines two days after reporting to the 17th. His diary entry for August 3, 1918, reads: “1st trip over lines, we got a good bit of archie and machine gun fire at Nieppe Forest. Saw no E.A.” Two days later, he records having strafed trenches around Dixmude; on the 10th he “Went to 19,000 ft. on aerial sentry. No E.A.” If Campbell’s records here are accurate, they provide further evidence of the 17th’s “abusing the King’s regulations,” which “abuse,” according to Otis Lowell Reed and George Roland, had begun over a month earlier.29a R.A.F. pilots were not supposed to cross the lines until they had been at least two weeks at the front, and the 17th, operating with the British 65th Wing, was supposed to follow R.A.F. regulations, but in this regard, evidently did not.

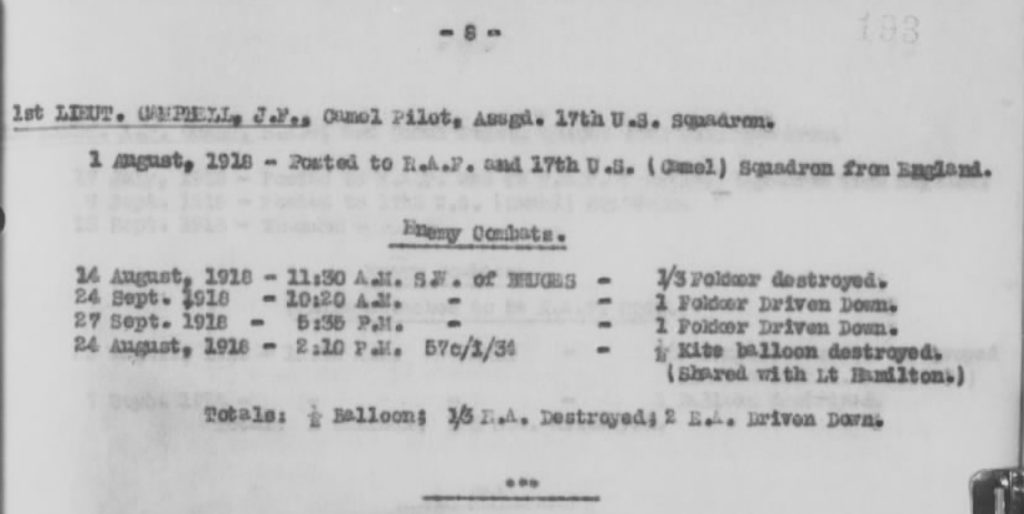

Having arrived so recently, and despite recent losses that meant the squadron was short of pilots, Campbell was not assigned to participate in the August 13, 1918, raid on the aerodrome at Varsenare, and there is no mention of the raid or preparations for it in his diary. The next day, the 14th, he wrote: “Started work in earnest today. The first show was escorting D.H.9 bombers to Bruges.” The 17th went out that morning to escort planes from No. 211 Squadron R.A.F. on a mission to photograph the aftermath of the Varsenare raid and to bomb Bruges. In the vicinity of Bruges, the patrol encountered six Fokkers and, on the return journey, after the photos had been taken, engaged with them. Campbell (flying Camel D9399), Robert Miles Todd, and Hamilton fired at a Fokker that was diving on a DH.9 piloted by Lt. Donald Ryan Harris, an American flying with 211. Harris was able to report that the pilot of the Fokker was apparently killed; Harris’s observer saw the plane crash.30 Campbell recorded that day that “I got my first Hun. Hamilton, Todd, and myself were all firing at him when he went down so I get credit for 1/3 hun destroyed officially.”

Campbell participated in an offensive patrol the afternoon of August 14, 1918, and in escort patrols on the 15th and 16th.

With the 17th Aero, Auxi-le-Château

On August 17, 1918, the 17th Aero Squadron moved from Petite Synthe about fifty-five miles south to the (British) Third Army area, specifically, to Auxi-le-Château, northwest of Doullens, in preparation for the push to recapture Bapaume and, ultimately, Cambrai. Like the 148th, which had moved south just before the Varsenare raid, the 17th was now part of the 13th Wing of the R.A.F.31 They were again to escort R.A.F. bombers, but also to do bombing and strafing. Campbell noted that “Our new front is between Albert and Arras so we should have plenty of work.” On the 19th he “Went on a tour of the lines between Arras and Albert,” and the next day, after ferrying a machine back from Hesdin and getting lost, had another “look at the lines” in preparation for the work of the 17th, which was to support General Byng’s Third Army and the push east beginning August 21, 1918.

Campbell’s diary entry for the opening day of the offensive reads: “Misty in the morning so we did not have to go over. Our troops have advanced about 5 miles. Escorted R.E 8s on a bombing expedition in the afternoon to Baupaume and were attacked by eight fokkers. We got two without losing anyone. Had an offensive patrol in the evening and trench straffed the last fifteen minutes. Hamilton, Todd, and myself went down on a baloon [sic] and got it in flames at 200 feet from the ground.” In fact, the first patrol flew well beyond Bapaume to Cambrai, and it apparently accounted for at least three enemy planes.32 The evening patrol did not take them as far. On the way back from dropping bombs on railroad tracks near St. Leger, C flight encountered the balloon near Beugnâtre, just northeast of Bapaume. Campbell “stood guard” while Hamilton and Todd attacked; Todd and Hamilton received credit for it.33

Campbell had a very close call the next day in the course of another escort patrol to Bapaume, when the patrol was attacked by a number of Fokkers. He wrote in his diary that “One got on my tail and nearly got me. One bullet went thru the center sections strut by my head and a bracing strut stopped another about an inch from my leg.” He was still (or again) flying D9399, and, according to one source, crashed on landing; the plane was sent away for repair.34 Campbell was unhurt and noted in his diary that he went out in the evening on another patrol, largely uneventful but for damage from anti-aircraft fire to the upper wing of Camel D6513, which he was now flying.34a

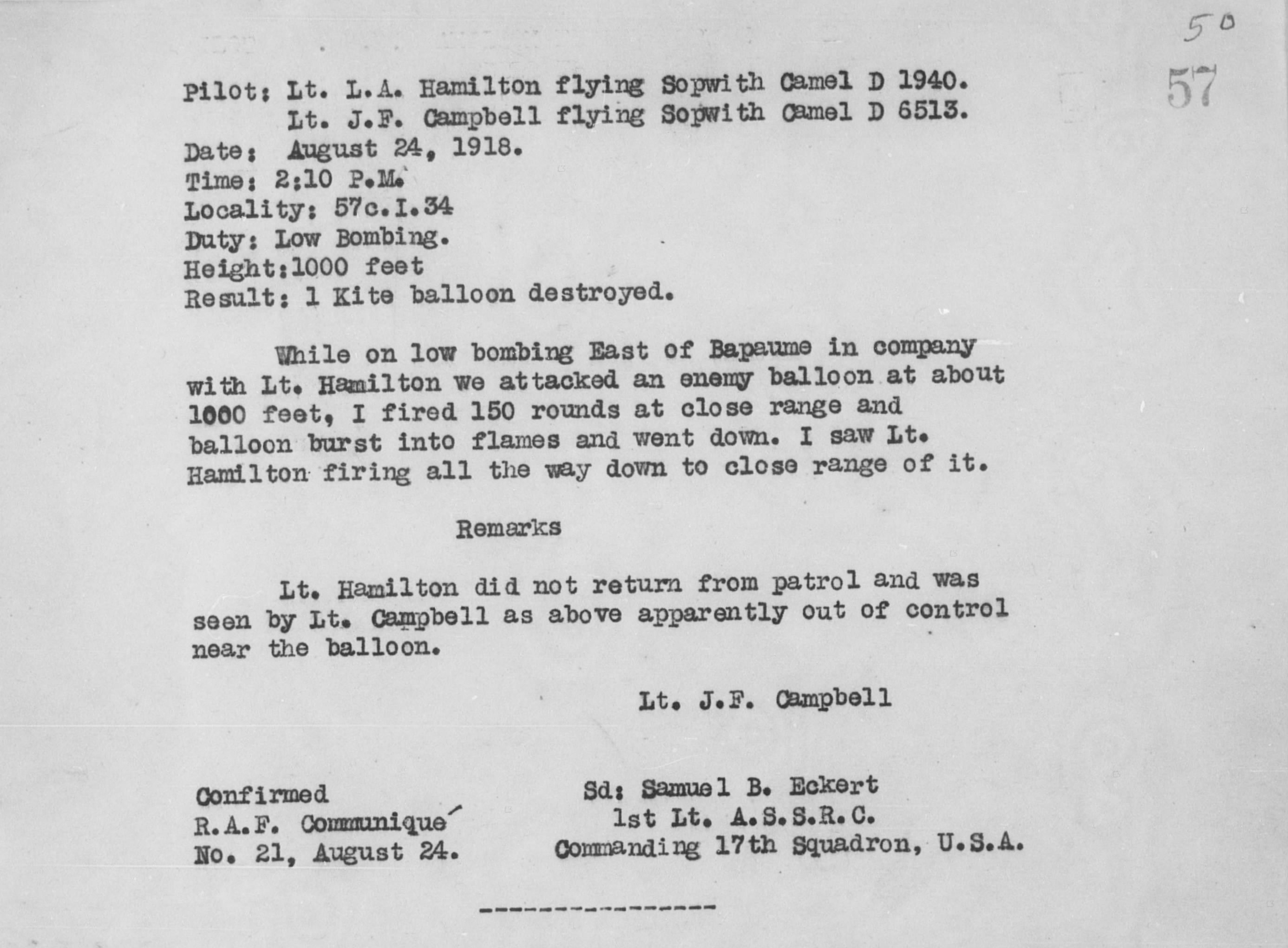

August 23, 1918, saw the 17th involved in “Another push today. In the morning we shot up and dropped bombs on troops and transports along the Bapaume Albert road. Machine gun fire from the ground was fierce. . . . I got two in my engine. . . . Murton Campbell was shot down about 5 miles in Hunland.” On August 24, 1918: “More ground straffing.” Campbell, again flying D6513, was responsible, along with Hamilton, for destroying an enemy balloon; he then witnessed Hamilton’s plane going down apparently out of control.35 Hamilton was later determined to have been killed.

Campbell was not involved in the encounter on August 26, 1918, when, despite bad weather and strong east winds, flights from the 17th Aero flew out to support the 148th and were attacked by a large number of enemy aircraft. He set out with C flight, but before he reached the lines, found his guns were not functioning and had to turn back.36 He wrote: “Providence was watching out for me however as our fellows ran into 40 Fokkers and only three out of the nine returned. . . . Dinner in the evening was a sad occasion with so many gone.”37 When C flight was rebuilt in the aftermath of that day, Campbell was eventually appointed deputy commander to the newly arrived William Thomas Clements, brought in from the 148th.38 In the meantime, the squadron was allowed “a couple of weeks rest to recuperate. Only five old men are left.”39

On August 28, 1918, Campbell wrote: “Led two formations of new fellows up to see the lines.”40 In his next entry, on September 14, 1918, he noted that the squadron had had “quite a rest since we were shot up,” and that their only war work was balloon line patrols and that they had recently “started work on wireless interruption [sic].” Wireless interception (as it was generally called) was a fairly new concept, involving triangulating from enemy radio signals to locate observation planes and then attempting to shoot them down; a group of pilots would be on standby to be sent out when an enemy observation plane’s location was received. Because the lines were moving east as the British push succeeded, the 17th was now quite a distance from where German observation planes were active. They set up a temporary field north of Bapaume near Beugnâtre, about thirty-five miles east of Auxi, where the flight “on call” would wait for the signal that an observation plane was out and about: “Had a few calls, but didn’t see any huns.”41

Campbell was still also flying offensive patrols, and it is not clear whether he was doing wireless interception or participating in an offensive patrol the next day when he “Had my first force landing this morning. The main lead from the magneto fused. Luckily there was a large field beneath me and I got down safely.” He records two uneventful O.P.s on the 16th. The next day, however, the pilots of C flight “were jumped by 16 Fokkers. There were only six of us so we had to run away.”42 Flying out of the advance field on September 18, 1918, Campbell was among those involved in attempting to bring down a German observation balloon. “We didn’t get the baloon [sic] but we stirred things up a little with our bombs. I—my machine—was hit in several places with archie but is still serviceable.”

With the 17th at Soncamp airfield near Sombrin

Meanwhile, word had come that the squadron was to relocate to Soncamp airfield near Sombrin, about seventeen miles east of Auxi-le-Château, and to work with No. 87 Squadron R.A.F. The move did not, however, mean a let up in patrols; Campbell flew offensive patrols on the 19th and the 20th, the latter being the day of their arrival at Sombrin.43 C flight was not on duty the next day and some of the pilots, perhaps including Campbell, used the squadron Cadillac for an outing to Boulogne.44

There are several eye witness accounts of an encounter the pilots of the 17th had the next morning (September 22, 1918) with German planes.45 In his diary that day, Campbell (now flying Camel F2146) wrote that “Twenty five huns attack [sic] twelve of us over Bourlon woods. We had a merry old scrap and in all got four of them. We lost Tillinghast [captured] and Thomas. One of them [Thomas] went down in flames. It was a horrible sight. We ran into a hun two seater (Hanoveraner) but he got away from us. These Huns certainly are good pilots and have lots of nerve. They say they are part of Richtofen’s old circus. #2 pursuit squadron.” Reed and Roland, in their reconstruction of this encounter, indicate that the enemy Fokkers were mainly from Jagdstaffel 26 and 27 of Jagdgeschwader III, rather than from Richthofen’s Jagdgeschwader I, but they were nonetheless formidable enemies. Had it not been for the skill of George Augustus Vaughn leading B flight, C flight—led by Clements and including Campbell—might well not have survived, apparently having been unaware of the danger they were in.46 Clements and Campbell filed a combat report regarding the Halberstadt two-seater (presumably Campbell’s “Hanoveraner”) they fired at, indecisively, over Inchy before breaking off at the approach of yet another flight of Fokkers.47

The next day’s patrol was uneventful for Campbell, but on September 24, 1918: “Had a fine scrap this morning. There were 27 huns and 15 of us. I was / We were in the top flight at 14,000 ft and as the huns went down on our bottom flight we went down on them. I got on ones [sic] tail and followed him down 5,000 feet pumping lead into him. I finally got quite close to him and as he started to half roll I saw my tracers going into the cockpit. He went down in a flat spin on his back but I didn’t see him crash as more were coming down on me. [Howard Clayton] Knotts went out this afternoon and saw him on his back near Havincourt [sic; sc. Havrincourt]. That makes two for me. We got 7 huns this morning without losing anyone.”48

The next day Campbell flew to St. Pol and visited No. 40 Squadron R.A.F. at nearby Brias. He noted in his diary that Anderson, who had been assigned to 40 shortly before Campbell went to the 17th, had been missing for a month.

On September 27, 1918, Campbell filed a combat report, his last, for a Fokker biplane driven down out of control east of Cambrai, but noted in his diary that “I doubt if I get him confirmed.”49

By this point in the war, German troops were retreating east as rapidly as they could, and, as squadron historian Mortimer Clapp writes, the 17th “helped break up the organization of his retreat toward the frontier . . . fighting hostile infantry and machine gun nests more than we fought Hun scouts and observation planes”; this is apparent from the 17th’s many bombing reports from the end of September and the first half of October.50 During this period Campbell provided a brief summary of his work with the 17th in a letter to his friend Crosthwaite: “Although we are a fighting squadron we have done nearly every kind of work except artillery shoots and photographs. . . . Lately we have been bombing and shooting up troops, trains and transports back of the lines. I have dropped over sixty bombs in the last nine days alone and as we drop them from such low altitudes we usually get good results. . . .”51

C flight leader Clements went on leave October 2, 1918, so Campbell took over as flight leader. He led his pilots on many bombing raids, sometimes twice daily, until bad weather set in on October 10, 1918. Campbell had a close call returning from a bombing mission over Caudry when “Archie shot my pressure pump off . . . about 10 miles back in hunland but I managed to get back to the lines alright”; “10 Fokkers followed me out.”52

Campbell’s remaining diary entries for this period are spare, most recording good news (including “Rain—Hurrah!”). In addition to noting towns recaptured (Cambrai, Caudry, Le Cateau) and leading Major Henry Fowler as part of his flight on October 9, 1918, Campbell wrote (on October 7, 1918) that “Good news came today. Curtis, Tipton, Todd, Frost, Weiss [sic] and Bittinger are prisoners.” Curtis had been with the 148th, William Dolley Tipton, Todd, Henry Bradley Frost, George Thomas Wise, and Howard Paul Bittinger with the 17th. The news regarding the first five presumably came from a post card sent by Tipton; long before it was received, Frost had succumbed to his injuries, and Bittinger also was dead.53

Campbell remarks at the close of his October letter to Crosthwaite that “I have been very lucky in scraps so far and have three huns and ½ a baloon [sic] to my credit. One hun hasn’t been confirmed yet. He was seen still spinning about 20 feet from the ground but no one saw him crash.” Campbell’s final score, was, indeed, four victories: three planes and one balloon.54

On leave, Toul, home

Clements arrived back at the squadron on about October 19, 1918, and Campbell was able to set out for England on leave on October 22. In London on the 26th he recorded that “[Theose Elwyn] Tillinghast (17sq), Anderson (40sq), and [John Owen] Donaldson (32 sq) arrived here tonight having escaped from Germany. They had a wonderful experience. 30 days walking across Belgium to the Holland border and finally cutting the electrically charged wire there. Don Harris who was shot down while we were at Dunkirk is a prisoner in Holland and is working at the American Embassy.” (Harris had helped confirm Campbell’s first, shared, combat victory, on August 14, 1918.)

Campbell was intending to begin the return journey to his squadron on November 5, 1918, but remained two more days in England until it was clear where he needed to go. At the end of October, the 17th Aero Squadron was reassigned from the British to the American sector, and by November 4, 1918, was in Toul. Travelling via Paris, where he stopped to take in a couple of shows, Campbell arrived in Toul on the eve of the armistice. The next day, November 11, 1918: “Had a great party in Nancy in the evening.”

Campbell took the opportunity while at Toul to try out “a 220 Spad. Don’t like them much.” “Had my first real crash. The engine cut out about 20ft from the ground as I was diving on the windward side of the aerodrome.” He was not hurt, but the plane had to be written off.55 He also, after some effort, was able to find his friend from Oxford days, Ed Moore, who was with the U.S. 8th Aero, an observation squadron now stationed nearby at Saizerais. On November 22, 1918, Campbell “Came back with Eddie in a DH.4 Liberty.”

Campbell was at Toul when group photos were being taken of various American squadrons. In a memo dated December 12, 1918, Frank Purdy Lahm, Chief of the U.S. Second Army Air Service, of which the 17th was now part, singled out Campbell, along with Clements, as among “the best types of pilots.”56

Officers and men of the 17th slowly made their way back to the United States. Campbell, now with the rank of captain, was among those who sailed on the U.S.S. Dakotan from St. Nazaire on March 7, 1919, arriving at Hoboken on March 20, 1919.57

Campbell returned to Michigan and to Albion College, graduating with class of 1919 and appearing in group photos of Albion men, including his friend Bob Crosthwaite, who had served in the military.58 He settled in his home town of Royal Oak and became, like his father, a building contractor.59

mrsmcq May 4, 2017, updated December 6, 201760

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

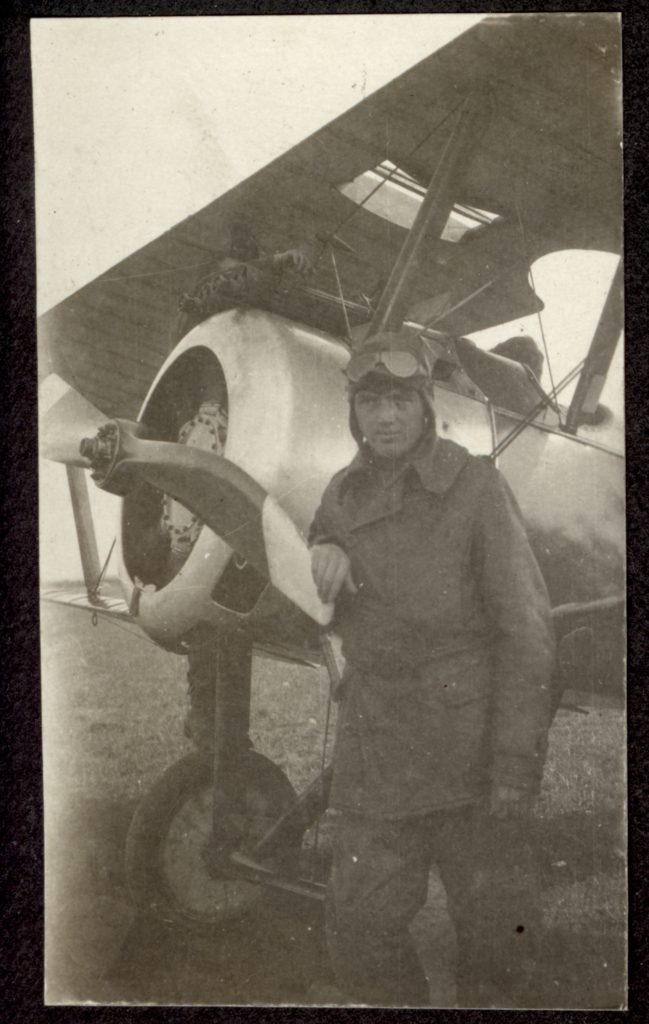

1 Campbell’s date and place of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Jesse Frank Campbell. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, Michigan, Death Records, 1867-1950, record for Jesse F Campbell. The photo is a detail from a photo in Clements’s photo album; see below.

2 See Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Lee Campbell; 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Lee Campbell; 1920 United States Federal Census, record for Joseph C [sic; sc. L] Campbell.

3 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

4 Jesse Campbell, Diary. Further quotations from the diary will be footnoted only when the date would otherwise not be evident.

5 On the ships in the convoy, see the commentary to the September 22, 1918, portion of Parr Hooper’s letter written on board the Carmania in Hooper, Somewhere in France.

6 Campbell, letters of December 3 and October 28, 1917 to Robert Orville Crosthwaite.

7 Campbell, Diary, October 22, 1917.

8 Campbell, Diary, entries for October 8 and October 17, 1917.

9 Campbell to Crosthwaite October 28, 1917. Men sent to the American 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun in the fall of 1917 found that the center was yet to be built, in part by them.

10 Campbell, letter to Crosthwaite, October 28, 1917.

11 Campbell, Diary, November 3, 1917.

12 Campbell, Diary, November 15, 1917; for the names of those posted with him, see Foss, diary entry for November 15, 1917.

13 Parenthetical remark from Campbell, Diary, entry for November 18, 1917; Campbell, letter to Crosthwaite, December 3, 1917 (punctuation and capitalization normalized).

14 Campbell, diary entries for November 20 and December 8, 1917.

15 Campbell, letter to Crosthwaite, December 3, 1917.

16 Campbell, Diary, December 19, 1917. What Bower was doing in Norwich and how Campbell came to know him is not known. A number of men of the second Oxford detachment were much taken with the Black Watch uniform of Joseph Baird at Oxford; possibly Campbell recognized Bower as a man of the same regiment (though of considerably higher rank).

17 See Campbell’s diary entry for December 18, 1917, on being “recommended for a Bristol Fighter.”

18 Campbell, Diary, December 26, 1917.

19 See Curtis’s letter of January 19, 1918. Campbell, in a letter to Crosthwaite of March 16, 1918, mentions being “billeted at a hotel in Radlett.”

20 Campbell, Diary, entries for December 8 and 11, 1917.

21 Campbell, Diary, January 8, 1918.

22 Campbell, Diary, February 27, 1918.

23 Jones, King of Air Fighters: Biography of Major “Mick” Mannock, V.C., D.S.O., M.C., p. 166, identifies “Major A.S. Dore” as the C.O. during 74’s period of mobilization; this was probably Alan Sydney Whitehorn Dore.

24 Campbell, Diary, March 25, 1918.

25 See cablegram 874-S, dated April 8, 1918, and 1303-R, dated May 13, 1918.

26 Campbell, Diary, May 18, 1918.

27 See also The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Jesse F. Campbell.

28 Campbell, Diary, June 23, 1918.

29 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 156. Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 220, indicates Jesse Campbell was initially assigned to No. 54 Squadron R.A.F., but Sloan has probably inadvertently confused him with Murton Llewellyn Campbell.

29a Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 35.

30 See Steve Russell’s reconstruction of Hamilton’s combat report based on a hand copied report in the Otis Reed files at the Air Force Historical Research Agency (in AFHRA 1141197) posted at “Combat reports. . . .” Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 62, describe the encounter. Endnote 16 to that page notes that Clapp does not include the relevant document for this shared combat victory, “although a copy of the claim in the British archives indicates it was confirmed.” Two DH.9 crews also shared credit: Geoffrey Harold Baker (not G. F. Baker) and H. Lindsay, flying DH.9 B7679, and William Dalrymple Gairdner (not Gardner) and Harry Morton Moodie, flying DH.9 B7603. See Great Britain, Royal Air Force, Royal Air Force Communiqués 1918, p. 165; Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, entry for D9399 on p. 141 (which is slightly confused regarding plane numbers); Shores, Franks, and Guest, Above the Trenches, p. 183; and Pentland, Royal Flying Corps, people indices.

30a Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 62, provide an account of the incident and supply the name of the German pilot. On the initial graves of Shearman and Case, see “Obituaries” in The Sigma Chi Quarterly, p. 590, which transcribes an article from the June 16, 1919, Chicago Daily Tribune.

31 Jesse Campbell’s diary entry for August 17, 1918, as well as Murton Campbell’s for the same day, provide the date of the move, which is unclear from other sources (Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 37; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 64-65; Jones, The War in the Air, p. 469).

32 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, combat reports on pp. 66–69; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 67–68.

33 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, combat report on pp. 69–70; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 68.

34 Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, p. 141, entry for D9399; see also Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 69.

34a Steve Russell, private note, provided Campbell’s plane number, based on a copy of the 17th Aero Squadron book among the Otis Reed files at the Air Force Historical Research Agency.

35 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 72–73; 102–3.

36 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 80.

37 Campbell, Diary, August 27 [sic], 1918; he has misdated this entry and the preceding.

38 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 87–89.

39 Campbell, Diary, August 27, 1918; this entry appears to be dated correctly.

40 According to a list of flight assignments on p. 135 of Reed and Roland’s Camel Drivers, the new men assigned August 28, 1918, were John A.(Albert?) Myers, Harold Goodman Shoemaker, George Augustus Vaughn, William Thomas Clements, and Thomas Lewis Moore, and any or all of these may have been the men Campbell led that day. (Reed and Roland note that the dates they provide do not consistently correspond to the dates provided by Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 155–60.)

41 On the temporary field for wireless interception, see Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 92.

42 On this encounter, see Clements’s diary entry for that day, as well as Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 93-94.

43 See Campbell’s diary entries for September 19 and 20, 1918.

44 Clements, diary entry for September 21, 1918.

45 See diary entries for that day by Clements and Noltenius (Ferko, ed., “Jagdflieger Friedrich Noltenius”), and Vaughn’s account, transcribed on pp. 175–77 of Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon and the 17th Aero Sqdn.”

46 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 98–100.

47 See the report on p. 83 of Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, which provides the serial number for Campbell’s plane.

48 See also Campbell’s combat report on pp. 85–86 of Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron. In Vaughn’s combat report on p. 86, his plane number should be F2164, not F2146 (the plane Campbell was flying).

49 See Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 89, for the combat report.

50 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squaderon, p. 51; see the bombing reports on pp. 106–45.

51 Campbell, letter to Crosthwaite, October 11, 1918.

52 Campbell, letter to Crosthwaite, October 11, 1918; Campbell, diary entry for October 4, 1918. Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 108, indicate that this incident occurred October 3, 1918. I have not been able to resolve the discrepancy.

53 See transcription of relevant passage from the card on p. 75 of Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron.

54 See Munsell, Air Service History, p. 193 (8); “Confirmed Victories U.S. Aero Squadron # 17 Attached to Royal Air Force”; and Thayer, America’s First Eagles, p. 320.

55 Campbell, diary, November 13 and 18, 1918.

56 “List of Officers Who Have Demonstrated Exceptional Ability,” p. 312.

57 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for 17th Aero Squadron, on U.S.S. Dakotan.

58 Ye Albonian, p. 29.

59 Ancestry.com, 1930 United States Federal Census, record for Jesse F Campbell.

60 Updates reflect information from Campbell’s diary.