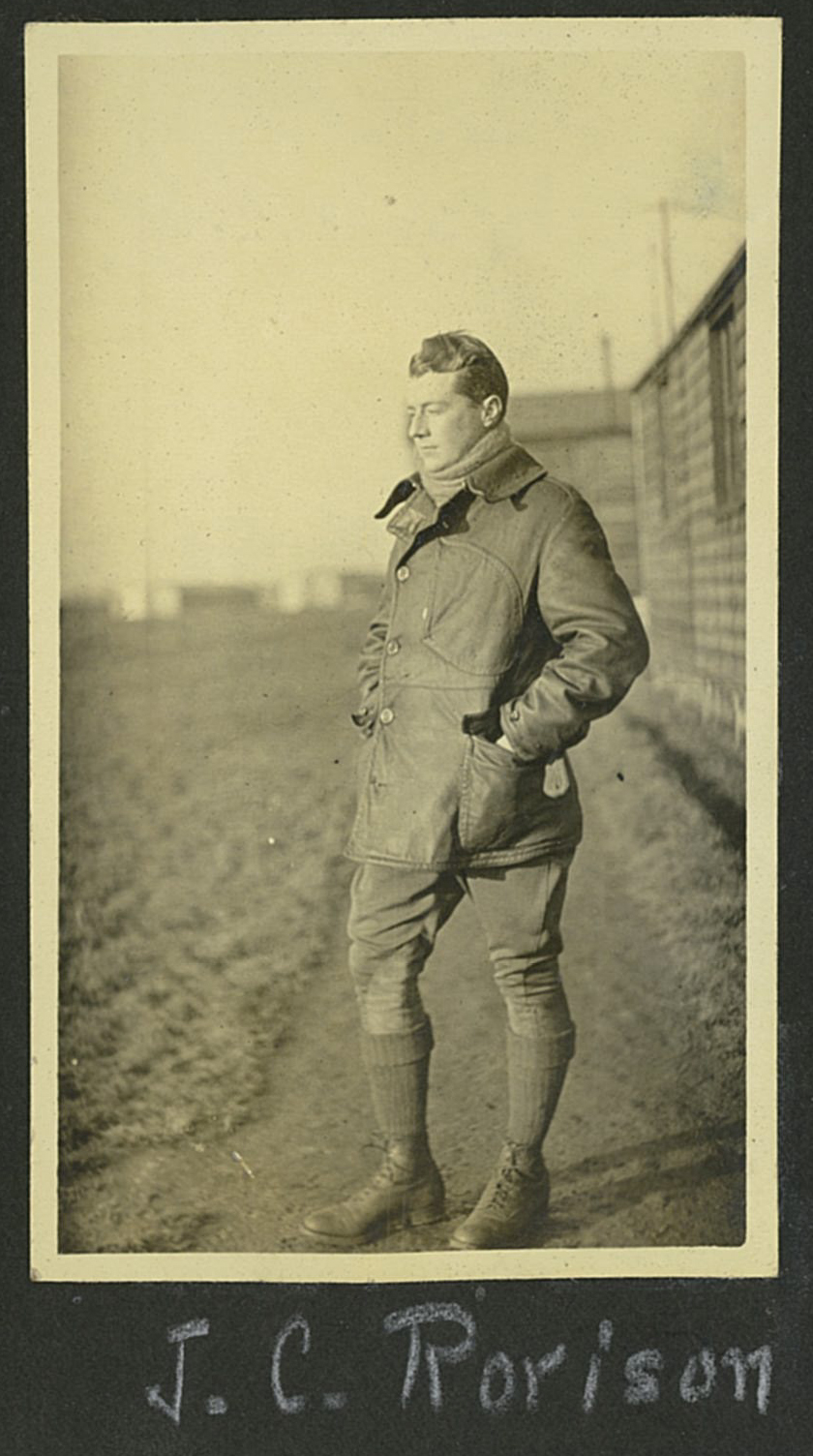

(Bakersville, North Carolina, October 22, 1894 – Morehead City, North Carolina, January 13, 1970).1

Oxford, Grantham, Northolt ✯ Shoreham-by-Sea ✯ Ayr, Turnberry, C.D.P. ✯ France & 85 Squadron ✯ Nos. 84 and 24 Squadrons ✯ With the 25th Aero and after

Rorison’s great-great-grandfather Alexander Rorison was born in Scotland and came with his parents to America around the time of the Revolutionary War, settling in New York.2 Alexander Rorison’s son, David Barber Rorison, was born in New York but around 1850 moved with his large family to Ypsilanti, Michigan. John Lee Rorison, in the next generation, served as a quartermaster sergeant in the Michigan infantry during the Civil War; he later moved about a good deal before settling in Bakersville, North Carolina, where he was involved in mica and emerald mining. John Lee Rorison’s son by his second marriage, Richard Basket Rorison, married Elizabeth Chadbourn in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1892. Her family also had northern roots: her mother was from Massachusetts and her father from Maine. The couple had two children: Harmon Chadbourn Rorison, born in 1893, and John Lee Chadbourn Rorison, born the following year (the latter sometimes used one, sometimes the other, sometimes both middle names or initials).

The young family relocated to Michigan, where John Lee Rorison’s first wife and her two children still lived. Elizabeth Chadbourn Rorison died there in 1897; Richard Basket Rorison appears to have remained in Michigan for a time before moving to Washington State, where his half-brother had also settled.3 The two motherless boys went to live with their Chadbourn grandparents and their mother’s older sister, Serena Chadbourn, in Wilmington, North Carolina.4

In about 1910 Serena Chadbourn and her two nephews moved to Charlottesville, Virginia.5 There the brothers attended the Jefferson School for Boys and then enrolled at the University of Virginia.6 John L. C. Rorison studied engineering there from 1914 through 1916.7 Rather impressively, in 1915, he filed a patent application for a phonograph or “automatic talking machine.”8 Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, also claims Rorison as an alumnus, class of 1919, although it is noted that he did not complete his degree, having left to join the war effort.9

Rorison enlisted in New York City at the end of June 191710 and evidently applied for and was accepted by the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. He went to the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University and graduated from ground school there on September 1, 1917 (his brother was in the class behind him).11 The course at O.S.U. was demanding, but Rorison’s time there was not all work. Parr Hooper, in the class ahead of him remarked in a letter home from early August 1917 that “Tomorrow . . . Mr. Rorrison [sic] and I are going to take out two girls. We may go canoeing.”12

Along with many of the men from the ground school classes of August 25 and September 1, 1917, Rorison chose or was chosen to train in Italy. It had initially been assumed the men would go to France for their actual flying training, but most were delighted when the possibility of “sunny Italy” was raised.

On the Thursday after graduation, Rorison and the others from his class expecting to go to Italy set out by train, in a private car, for New York and the air field at Mineola on Long Island, where they were based for the next week and a half.13 On September 18, 1917, as Rorison’s ground school classmate Murton Llewellyn Campbell recounted: “We piled out at 4 A.M., had breakfast early and ‘fell in’ at 6 in front of Gate No. 6 with full equipment. We marched over to Garden City and took the Penna. to Long Island City, where we embarked on the Gen. Meigs, which took us down East River and up the Hudson to a dock. Then we walked aboard the Cunard liner, Carmania. . . . ”14 After an initial stop at Halifax, the Carmania set out as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. The 150 men of the detachment travelled first class and had plenty of leisure, apart from daily Italian lessons conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them, and submarine watch duty towards the end of the voyage.

Oxford, Grantham, Northolt

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. The “Italian detachment” thus became the “second Oxford detachment” (another detachment of American aviators in training having arrived at Oxford a month previously). It was initially thought that the course would take six weeks, but the cadets left Oxford after four weeks. In early November 1917 twenty men were posted to Stamford to begin flying training, but the others, including Rorison, set out from Oxford on November 3, 1917, for Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend a machine gunnery school. Hooper, also sent to Grantham, remarked: “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”15

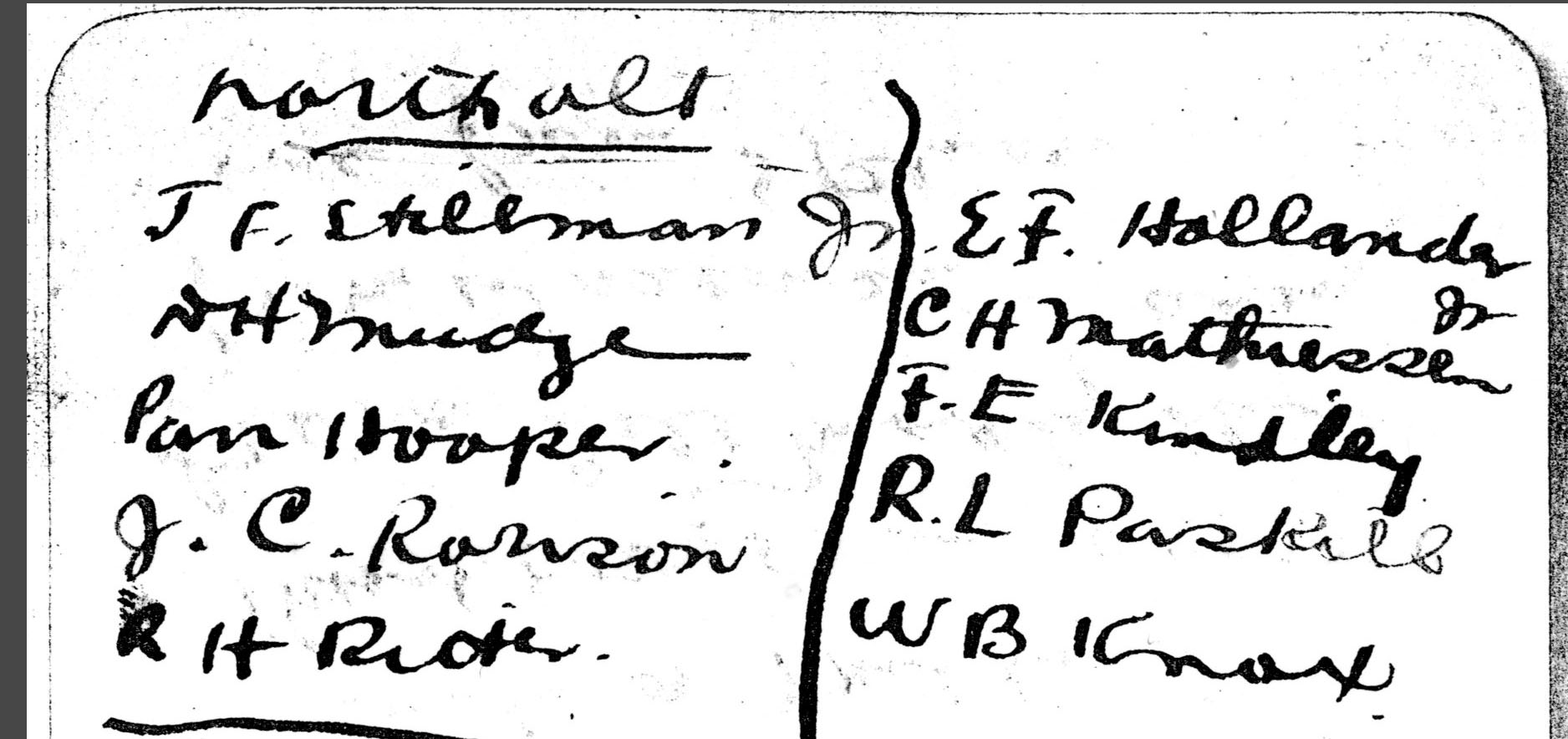

The men spent the next two weeks learning about and practicing with the Vickers machine gun. Just as they were finishing and facing the prospect of two weeks on the Lewis gun, they learned that fifty places had opened up at various R.F.C. squadrons, and Rorison was among those selected to fill them. Along with nine others, he was posted to Northolt, on the northwest outskirts of London.16 Hooper, also assigned to Northolt, wrote home a few days later that “We packed up Sunday evening [November 18, 1917] and loaded our luggage on motor lurries [sic] at sunrise Monday. The train for London left at 7:30. We had a 1st class compartment and read the papers and watched the scenery. We arrived at King’s Cross Station unexpectedly soon 10:45. Fred [Stillman] and Dud Mudge went up to Paddington Station with our luggage on horse drawn busses. Rorison and ‘Rit’ [Roland Hammond Ritter] and I started out to see London before we took the train for Northolt at 1:57 from Paddington.”17

Of Northolt, Hooper wrote: “Everybody here are officers except the mechanics. There are about 150 men training, 2 elementary squadrons and one advanced. We 10 Americans (5 in the 2nd squadron and 5 in the 4th squadron) are ranked as cadets but are treated as officers.” Rorison, along with Hooper, was in No. 2 T.S.18 Hooper continues: “The field is about ½ mile square. Lined on the north side are the hangars, large substantial corrugated iron ones, and behind them a row of shops and instructional rooms. On the adjacent side are the long low houses, so called huts. One group for the men and one for the officers. Also the headquarters, offices, and mess buildings. We live in nice, unfurnished rooms in the huts, 2 officers to a room and a man servant to each hut of 6 rooms. . . . The Major, the staff, flying instructors and all of us have the same mess.”19

Training began almost immediately. Hooper flew for the first time on November 22, 1917; Rorison’s experience was presumably similar. “In good calm weather flying goes on all day from sunrise to sunset with time out for the instructor to eat and have tea. The elementary squadrons use a very old type machine but one which they say is excellent to learn on because it has no inherent stability and must be flown (meaning controlled) all the time. . . . I have been here 4 days and have been up 3 times, total 65 minutes.”20 The “very old type machine” was the Maurice Farman S. 11 Shorthorn or “Rumpty,” ubiquitous at R.F.C. elementary training squadrons at this time. Conrad Henry Matthiessen, Field Eugene Kindley, and Hooper are documented as having flown solo for the first time in early December, 1917, and, again, Rorison’s experience was presumably similar.21

No. 3 T.S. at Shoreham-by-Sea

Most of the second Oxford detachment men at Northolt were posted to advanced training squadrons before Christmas; Rorison, however, remained at Northolt until January 11, 1918.22 The next day he joined his friend and fellow second Oxford detachment member Roy Olin Garver at No. 3 Training Squadron at Shoreham-by-Sea, near Brighton on England’s south coast; Garver had been in the class ahead of Rorison at O.S.U.

Rorison, like the other men with whom he had trained at Northolt, was in line to fly scouts, i.e., single-seater fighter planes, rather than two-seater bombing or reconnaissance planes. It is thus likely that his training at Shoreham resembled Hooper’s at London Colney: initial instruction on Avros, followed by flights on Sopwith Pups. S.E.5a’s and Camels were also among the aircraft available at Shoreham,23 and it was on one of the latter that Garver was killed on January 28, 1918. Rorison had the unhappy task of writing to Garver’s mother in the aftermath of the fatal crash: “Having for eight months been a very warm friend of Roy’s, I am writing on this very sad occasion to extend to you the most sincere sympathy of his many friends here.”24

It was early in his training for Garver to have flown a Camel (his O.S.U. classmate Ritter remarked that Garver “was rushed thru too fast”25), and I would surmise that, especially in the aftermath of this incident, Rorison’s training at Shoreham proceeded more cautiously. Nevertheless, he made good progress, as he was recommended for his commission as a first lieutenant by early March 1918; Pershing forwarded his name to Washington in a cable dated March 7, 1918, and the confirming cable from Washington is dated ten days later.26

Somewhat ironically, John L. C. Rorison’s commission came through over three months after that of his brother, who had been behind him in ground school and who would have had less advanced training.27 At some point the two had an opportunity to compare experiences. Harmon Chadbourn Rorison arrived in England in January 1918, having crossed the Atlantic, also on the Carmania, as a member of the 25th Aero Squadron (to which John L. C. Rorison would be assigned late in the war).28 Harmon alludes to a meeting with his brother “several months ago” in a letter home published in a Wilmington newspaper in early June 1918.29

Ayr, Turnberry, C.D.P.

After finishing up at Shoreham-by-Sea Rorison was posted to the School of Aerial Fighting at Ayr on the west coast of Scotland on March 26, 1918; from there, he went to the School of Aerial Gunnery at nearby Turnberry on April 23, 1918, where he remained until May 12, 1918.30 This is a bit puzzling, as pilots typically went first to Turnberry before their final training in aerial fighting at Ayr. In any case, a photo taken by Rorison documents his presence at Ayr on or very shortly after April 23, 1918: it is of the wreckage of Bristol Fighter C4689, which second Oxford detachment member Norman K. Berry was piloting on that date when it crashed and burned.31

Rorison’s training at Ayr presumably resembled that of Hooper and Francis Kinloch Read, whose time there overlapped with his. Their log books show them putting in a good number of hours flying Avros and Spads—while at Ayr Rorison photographed Read flying a Spad 7 (A9140), which Read’s log book shows him to have flown several times during the period from April 11 to April 23, 1918.32 After practicing formation flying, fighting, and stunting in Avros and Spads, the men moved on to S.E.5a’s, which all three, Hooper, Read, and Rorison, would fly operationally in France.

Accounts of training at the S.A.G. at Turnberry mention long, tedious hours in class. Second Oxford detachment member Elliott White Springs, in his diary, remarked “Very boring this machine gun stuff”; in War Birds this sentiment was transformed into “We go to machine gun classes for ten hours a day for ten days. They run us to death and we freeze and starve.”33 There was some compensation in that the men’s living quarters at the Turnberry Hotel were luxurious, and at least some of the men enjoyed playing golf and exploring the surrounding countryside. The course ended with oral exams and practice firing a gun from a B.E.2c.34

Once having completed their training in Scotland, some men were posted immediately to France, but many, like Rorison, were assigned to the Central Despatch Pool and given ferrying jobs, flying planes, S.E.5s and Bristol Fighters in Rorison’s case, within England and sometimes across to France.35

France & 85 Squadron

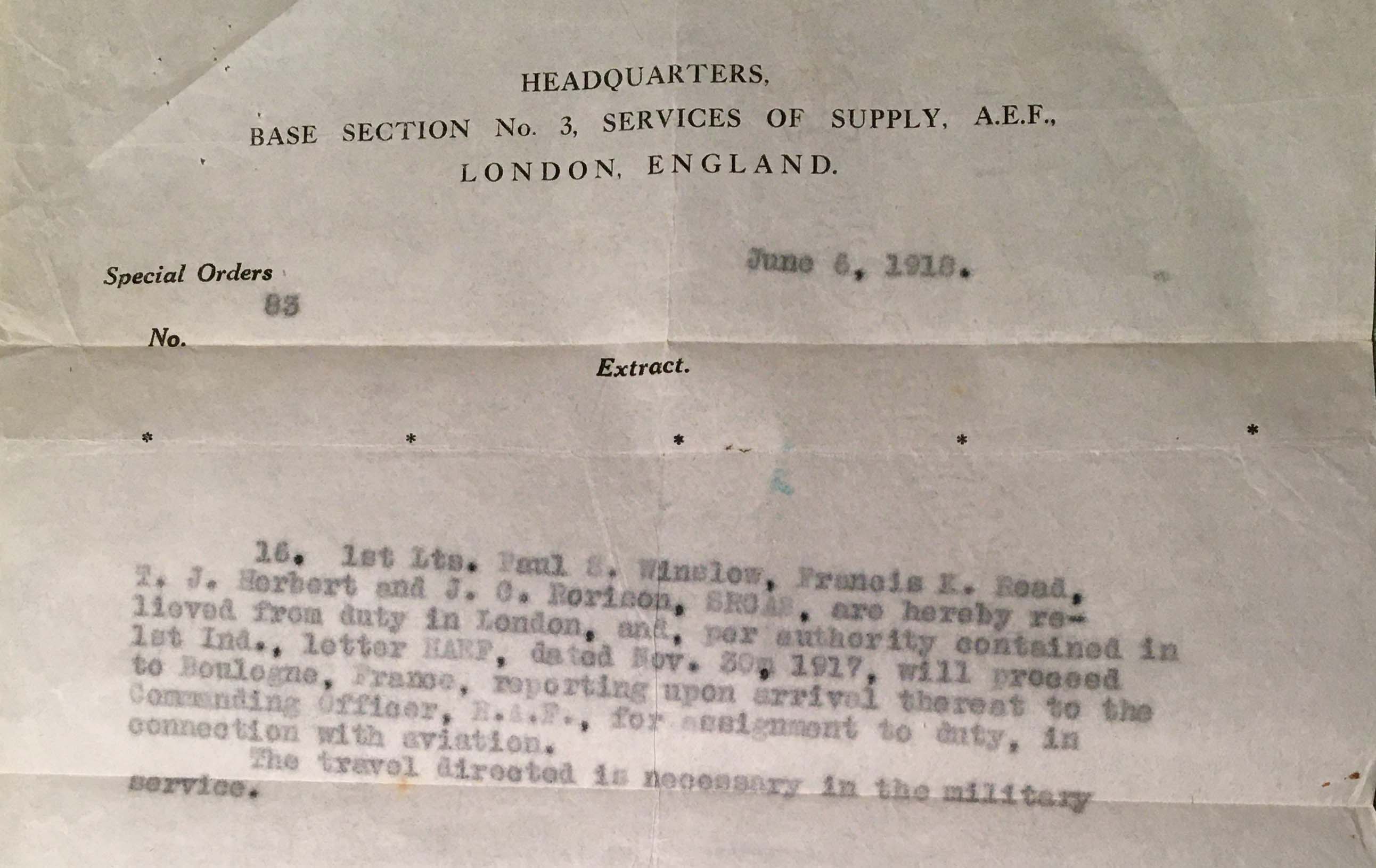

On June 6, 1918, Rorison, and three other men who had been serving as ferry pilots—Thomas John Herbert and Read of the second Oxford detachment, and Paul Stuart Winslow of the first—were ordered to Boulogne to report “for assignment to duty, in connection with aviation.”36

Rorison spent about a week at the pilots pool at Rang du Fliers on the Channel coast south of Boulogne before being posted on June 15, 1918, to No. 85 Squadron R.A.F.37 No. 85, equipped with S.E.5a’s, had become operational the previous month and had initially been stationed at Petite Synthe near Dunkirk on the coast. On June 11, 1918, a few days before Rorison arrived, the squadron relocated to St. Omer, about twenty miles inland.38 Like No. 74 Squadron at nearby Clairmarais, 85 was in the 11th Wing and part of II Brigade supporting the British Second Army.39 The Second Army front ran from Houthulst Forest, 10 miles north of Ypres, down to Nieppe Forest, about twenty miles southwest of Ypres. This sector was relatively quiet at this point in the war.40

Second Oxford detachment members Laurence Kingsley Callahan, John McGavock Grider, and Springs had been assigned to No. 85 when it became operational. The War Birds entry for June 17, 1918, notes the addition of Rorison: “We have another one of the Oxford Cadets with us, Rorison, who is assigned to B flight. He’s from Wilmington, N.C. He’s a serious youth and can figure out anything on paper with a slide rule.”

Grider went missing, later determined killed, shortly after Rorison arrived, and Springs was injured a little over a week later and left the squadron not long afterwards. There were also changes in squadron leadership. William Avery “Billy” Bishop, who had been instrumental in securing places for Callahan, Grider, and Springs in the squadron, left No. 85 on June 19, 1918, which was also the day that second Oxford detachment member Guy Maynard Baldwin joined the squadron. George Brindley Aufrère Baker was interim C.O. until the arrival of Edward Corringham “Mick” Mannock, who led the squadron from July 5, 1918, until his death on July 26, 1918.41

Efforts to locate a copy of 85’s record book for 1918 have been unsuccessful, so that details of the squadron’s operations must be reconstructed from other sources.42 G.H. Cunningham, in his biography of 85 Squadron pilot Malcolm Charles McGregor, provides an overview of the squadron’s activities: “Three patrols were undertaken daily by the squadron, each flight taking, in rotation, the dawn, morning or afternoon one. It was customary . . . for the Commanding Officer to participate in one daily patrol. The last was regarded as being the best, since the enemy was usually most active in the afternoon. Sometimes all flights would participate; and occasionally two or more squadrons would combine and, in layered formations, scour the sky for Germans.”43

There are two extant accounts of Rorison’s activities with No. 85; one is among the “Extracts of Experiences of Individual Pilots” in Munsell’s “Air Service History”44 and the other is the “‘History sheet’ for John C. Rorison detailing military career, undated” in the Harmon C. Rorison Private Papers collection in the Randall Library at University of North Carolina at Wilmington. In the latter Rorison indicates that he made his “first flight over the lines” on June 18, 1918, just three days after his arrival. This was almost certainly an orientation flight rather than an offensive patrol.

The next entry in the “History sheet” is dated July 8, 1918: “My flight attacked a patrol of enemy machines over Armentieres, France. I put in several good bursts within close range, at two of them, which were destroyed. (Official R.A.F. credits of one each, given to two of my partners.)” It is probable that this entry refers to an engagement the evening of July 7, 1918, when four pilots of 85 Squadron—Spencer Bertram Horn, Walter Hunt Longton, Mannock, and John Weston Warner—accounted for six Fokker DVIIs (either crashed or driven down out of control) west of Armentières. Confusion as to the correct date may have arisen from the R.A.F. record keeping practice of closing entries for a given day at 4 p.m. and including later events with entries for the subsequent day.45

On July 10, 1918, Rorison was involved in another engagement, not far from the combats on the 7th. The accounts in Munsell’s “Air Service History” and the “History sheet” are almost identical; the latter specifies the location: “With my flight commander, I attacked a ‘Hannoveraner’ over Merville, France. Each of us put in long bursts at close range and the machine was destroyed. (Official R.A.F. credit given to my flight commander.)” Rorison’s flight commander was apparently Longton, who claimed credit this day for a Hannoveraner destroyed at 6:50 a.m. near Merville.46

Rorison was involved in a further air combat on July 13, 1918; again the accounts in Munsell and the “History sheet” are similar, with the latter specifying a location: “Two of us attacked a hostile machine near Fleurbaix, France, and shot it to pieces from within close range. (Official R.A.F. credit given to my partner.” (Fleurbaix is about three miles southwest of Armentières.) This engagement is almost certainly the one described by Callahan in the narrative of his combat report for that day: “Followed Lieut. McGregor into fight with about 18 Pfalz and Fokker E.A. I fired 50 rounds into Fokker which went down completely out of control and crashed near Armentieres. I saw Captain Dixon fire upon E.A. which went down completely out of control and crashed.”47 Callahan was credited with a Fokker DVII, and George Clapham Dixon with a Pfalz DIII, both at 8:30 p.m.48 It is not evident which pilot—Callahan or Dixon—is the one to whom Rorison refers as “my partner.”

The next day, July 14, 1918, pilots of No. 85 Squadron set out in the morning on an offensive patrol that led to an engagement in the vicinity of Merville and Estaires between about 8:30 and 9:05 a.m. and resulted in five combat victory credits distributed among five pilots, including Rorison, who was flying S.E.5a B7870.49 Rorison’s combat report narrative reads, in part:

Diving with Capt. Dixon’s patrol on E.A. patrol, I got into position on the tail of one Pfalz Scout and fired several bursts. In the general combat which followed I lost sight of this E.A. [M]eantime another E.A. dived on me from above, whereupon I turned and engaged this E.A. which was a Fokker Scout, getting in several good bursts at very close range at height of 1,000 feet, whereupon E.A. dived steeply away and I saw the debris on the ground in a field S.W. of Estaires, being then at 500 feet.50

There are also descriptions of this combat in the “History sheet” and in Munsell’s “Air Service History.” In the latter Rorison states that “I engaged one of them [Fokkers] and fired long bursts at him at close range until we were less than 500 feet high, when the ‘Fokker’ dove, crashing into the ground.” An interpolation by “W[arren] P[erry] M[unsell]” follows this account: “There is no official record of this at Headquarters R.A.F.”51 This may perhaps be explained by a note appended to Rorison’s combat report: “Lieut. Rorison landed later then [sic] the main body of the patrols hence the delay in the report, and which also accounts for this decisive result not having been advised to the Wing H.Q.s together with the originally submitted results.”52 Nonetheless, Rorison is among the pilots of 85 credited in the Royal Air Force Communiqués with having brought down enemy aircraft during the period from July 8 through July 14, 1918.53 As adumbrated by Munsell’s remark, the information apparently never reached the American authorities, and Rorison’s name is absent from U.S. listings of combat victories.54

Records of No. 85 Squadron combat claims indicate that 85 continued flying offensive patrols over the next two weeks, and it is likely that Rorison participated in some of them. However not until the last day of July is there an indication of his involvement. The entry for July 31, 1918, on the “History sheet” reads: “With my flight commander, I attacked an ‘Albatross’ two-seater over Capingham [sic; sc. Capinghem?], France. Our shots pierced his gasoline tank and the machine burst into flames. (Official R.A.F. credit given to my partner.)” Arthur Clunie Randall, B flight commander—and successor to Mannock as squadron C.O.—filed a combat report for July 31, 1918, claiming a “Two-seater Albatross” destroyed southeast of Estaires at 8:05 p.m.; Rorison confirmed the claim.55 This is not the only occasion when the location provided by Rorison for an engagement (Capinghem; “far over the lines”56) seems to be at variance with the locations provided by the claimant (“S.E. Estaires”; Vieille Chapelle), but, particularly in the absence of the details that the record book would presumably provide, it is hard to tell whether this is significant.

Rorison’s last recorded combat involvement while he was with No 85 Squadron occurred on August 3, 1918: “Two of us attacked a hostile machine over Bois de Ploegsteert, Belgium, and we both fired bursts at close range. Pieces flew off of the machine and it crashed into the ground. (Official R.A.F. credit given to my partner.)”57 His “partner” this day was apparently McGregor, who filed a combat report and also described the encounter in more detail in a letter to a friend. The combat report indicates that the combat occurred at 8:10 a.m. east of Bailleul (which would accord with Rorison’s “Bois de Ploegsteert”): “While leading patrol of three S.E.s I obtained position in the sun east of five E.A. which were being decoyed by patrol lead [sic] by Lieut. Longton. We attacked when E.A. dived on bottom patrol. Getting on one E.A.’s tail I fired a good burst from both guns. . . . I observed E.A. going down completely out of control. . . .”58 McGregor’s letter indicates that his flight had started at 17,500 feet, above the other flight at 12,000 feet; once “the scrap” started, he estimated that there were as many as thirty Fokkers involved.59

Nos. 84 and 24 Squadrons

Five days after this “dog fight” Rorison received word that he was being transferred to another squadron. The entry in the “History sheet” reads “On August 8th. 1918, a call from the 22nd. Wing, came to the 85th.. Squadron, for two ‘experienced pilots’ to replace casualties, in the big British push off of Amiens. On the following day I went to the 22nd. Wing as one of those pilots, and was posted to the 84th. Squadron.”

22nd Wing, and thus No. 84 Squadron, was at Bertangles; it was in V Brigade, which was at this time supporting Fourth Army, whose front east of Amiens ran approximately from Albert, north of the Somme, to the French Army front south of the Somme about three miles south of Villers-Bretonneux.60 The other pilot posted to 84 was Douglas Carruthers.61

A list of casualties documented for the R.A.F. on August 8, 1918, makes clear the extent of R.A.F. losses on that day and helps explain Rorison’s abrupt transfer; the R.A.F.’s pilot-intensive effort to cut off the German retreat by bombing bridges over the Somme was especially costly that day and the next.62 I find no record of Rorison’s activities during this period, but it seems safe to assume that he was involved in offensive patrols and/or bombing raids in connection with the Battle of Amiens.

This battle, which opened the Hundred Days Offensive, ended on August 12, 1918; two days later Rorison was reposted from 84 Squadron to 24 Squadron63—also part of 22nd Wing Wing and just arrived at Bertangles from Conteville; Rorison was assigned to B flight.63a No. 85 Squadron had also been relocated to Bertangles the preceding day, and it would seem logical for Rorison to have returned to his old squadron. An entry in War Birds, however, perhaps explains why this did not happen: “24 squadron got caught out by a bunch of these new Fokkers and got shot up badly. They had to have some men with experience so we sent over Capt. Caruthers [sic] and Rorison.”64 Apropos of Rorison’s assignment to No. 24 Squadron the “History sheet” notes that 24 “was then engaged mostly in attacking hostile ground targets.” Probably already with his assignment to 84 and certainly now with No. 24 Squadron, the type of mission Rorison was involved in changed from offensive patrols seeking out enemy aircraft to (often even more dangerous) ground strafing and bombing missions.

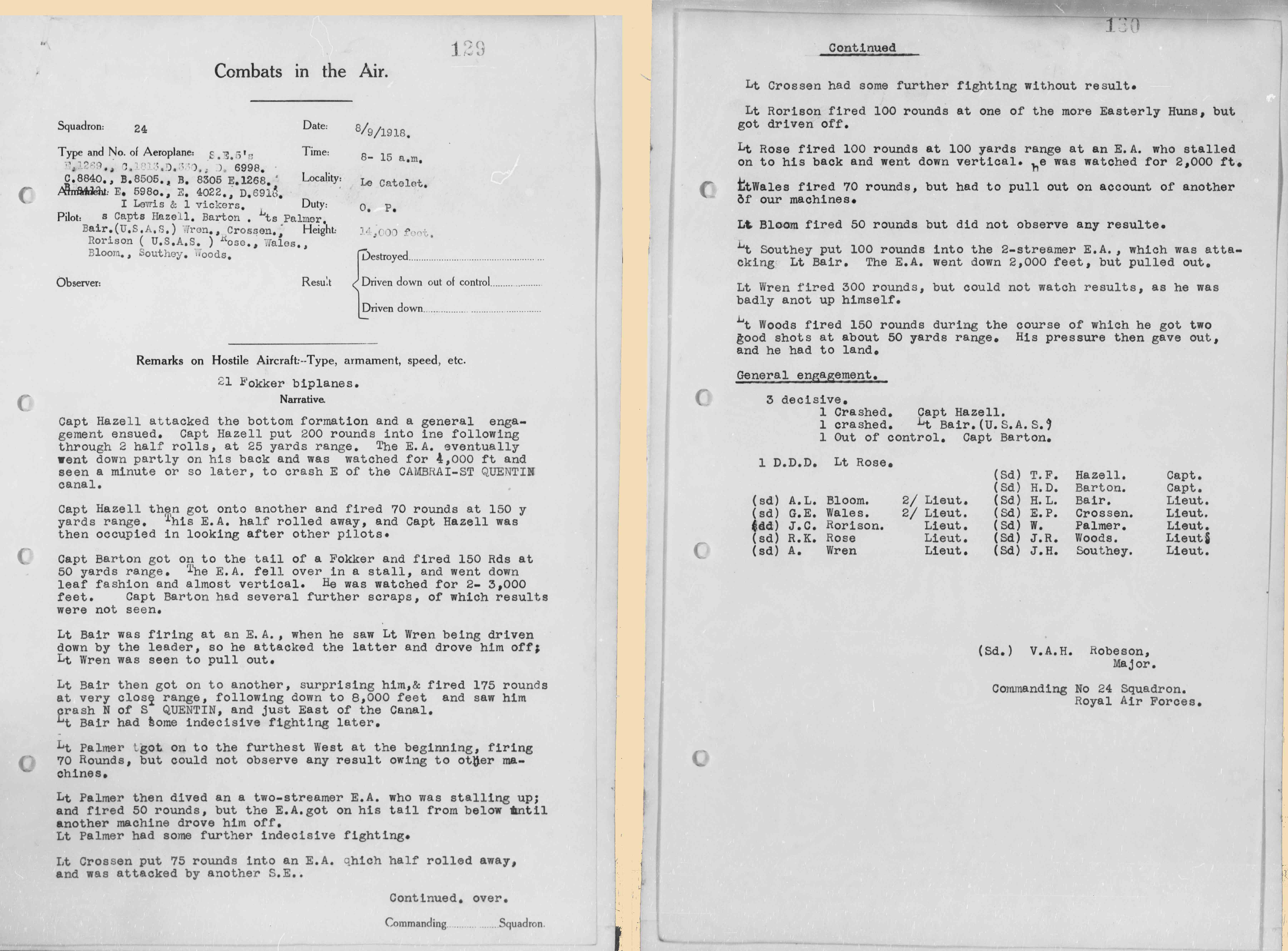

Rorison recorded his involvement in one engagement while he was with No. 24 Squadron. On September 8, 1918, “while our squadron of 15 machines was patroling twenty miles over the lines, we were attacked by three ‘Fokkers’ formations of 16 machines each. A thick dog-fight ensued. One of the ‘Fokkers’ at which I fired bursts from within close range, spun into the ground. (Official R.A.F. credit given to one of the attacking pilots.)” This is from Munsell’s “Air Service History”; the “History sheet” notes that the No. 24 Squadron flight “was patrolling over St. Quentin.” There are records of three claims made by 24 Squadron members at 8:15 a.m. (British time) on September 8, 1918, all in the vicinity of Le Catelet, about ten miles north of Saint-Quentin: Horace Dale Barton claimed a Fokker DVII out of control, and Thomas Falcon Hazell and Hilbert Leigh Bair each claimed a Fokker DVII “crashed.”65

A diary cited by Illingworth in his history of the squadron mentions that planes from this patrol “landed at Cappy, whither ‘46’ and ourselves moved during the morning.” Illingworth describes how, as a consequence of the Allied offensive, “the enemy was forced into a rapid withdrawal of his front. . . . The Squadrons had to keep pace with the retiring enemy, and consequently we find No. 24 . . . almost continually on the move.”65a

With the 25th Aero and after

Four days later, on September 12, 1918, Rorison left No. 24 Squadron and the R.A.F., having been posted to the (American) No. 3 Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun in the Loire region of central France.66 According to Paul Stuart Winslow—with whom Rorison had been posted from England to France in June—he and Rorison were part of a group of thirteen American R.A.F. pilots ordered at this time to the 3rd A.I.C. They “reported to Headquarters and were told to come back tomorrow. . . . When we reported to Major [Thomas George] Lamphier [sic; sc. Lanphier], we were told that we were ordered here by mistake, and they did not know what to do with us, but would wire Tours and let us know tomorrow.”67 After much confusion the men went their various ways, and Rorison was sent to Colombey-les-Belles.68 From there he was posted on September 23, 1918, to the American 25th Aero69; this was the squadron to which his brother had been assigned when he sailed to Europe at the beginning of the year, but Harmon Chadbourn Rorison was transferred out shortly after arriving in England.70 A number of other first and second Oxford detachment members were assigned to the 25th around the same time as Rorison, including Baldwin, who had served with Rorison in No. 85.

On October 24, 1918, the squadron moved to Toul, where it joined the 17th, 148th and 141st Aero Squadrons to form the Fourth Pursuit Group of the American Second Army at Gengoult aerodrome.71 Second Oxford detachment member Donald Swett Poler recalled how “Every pilot that came into the 25th Squadron, as he reported, got his orders to go over to England and bring back an S.E.5a. . . . I made three trips”; Baldwin’s recollection was similar.72 The 25th did not receive its full complement of S.E.5s until well into November, but did became nominally operational, thanks to a flight over the lines on November 10, 1918.73 Photos were taken of the squadron at Toul, and Rorison appears fifth from the left in one taken in front of a Spad XIII.

After the armistice Rorison returned to England and on February 16, 1919, sailed from Liverpool on the Olympic; after a stop at Brest to pick up more passengers, the Olympic set out on February 18, 1919, for the Atlantic crossing and arrived at New York on February 24, 1919.74 Rorison shared a stateroom with second Oxford detachment member Eugene Hoy Barksdale, who had also been with the 25th at the end of the war.75 They arrived at New York on February 24, 1919.

Rorison for a time lived in New York City and pursued business interests.76 In 1922 he applied for a passport in order to travel to China and look into shipping, apparently in connection with his father’s employment at Skinner & Eddy Shipbuilding Corporaton in Seattle.77 At some point he returned to and settled in North Carolina where he “worked in several capacities with the Marines at Havelock and at Cherry Point, N.C.”78 He was among those who helped James J. Sloan, Ola Sater, and John J. Smith identify the members of the Oxford detachments and their service activities.79

mrsmcq June 15, 2023

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Rorison’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917–1919, record for John Chadbourne [sic] Rorison. I have not found a World War I draft registration for Rorison. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, North Carolina, U.S., Death Certificates, 1909-1976, record for John Chadbourn Rorison. The photo is from the Harmon C. Rorison Private Papers at the Randall Library Special Collections at the William Madison Randall Library of the University of North Carolina, Wilmington. My thanks to the library for permission to reproduce it. See here for larger version.

2 On the early Rorison family, see MacKenzie, Colonial Families of the United States of America, pp. 451–52.

3 On the Rorisons and Chadbourns, see documents available at Ancestry.com.

4 See “Rorison, Harmon Chadbourn, 1893-1976.”

5 Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Serena Chadbourn (and household).

6 See University of Virginia, Corks and Curls, vol. 28, p. 375.

7 University of Virginia Alumni Office, Directory of the Living Alumni of the University of Virginia: Centennial Edition, p. 141.

8 United States Patent Office, Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office, vol. 268, pp. 396–97.

9 “In Memory,” Trinity Reporter.

10 Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917–1919, record for John Chadbourne [sic] Rorison

11 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917], and “Ground School Graduations [for September 8, 1917].”

12 Hooper, letter of August 4, 1917 (in my possession, not published).

13 Murton Capbell, diary entry for September 6, 1917, et. seq.

14 Murton Campbell, diary entry for September 18, 1917.

15 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

16 Foss’s diary entry for November 15, 1917, lists those being posted

17 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917.

18 On Rorison’s assignment to No. 2 T.S., see Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” pp. 32 and 36.

19 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917.

20 Ibid.

21 On Matthiessen and Hooper, see Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 4, 1917; on Kindley, see Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 24.

22 Dates of Rorison’s service are taken from “‘History sheet’ for John C. Rorison detailing military career, undated,” and from the “Chronology of Service” on p. 33 of Doyle’s “War Birds Pictorial.” Rorison’s R.A.F. service record (The National Archives [United Kingdom], Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for J. C. Rorison) notes only his assignment to 85 Squadron and a puzzling and garbled, or completely incorrect, remark related to leave in England.

23 Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 279.

24 Rorison’s letter is printed in “Letters Tell Details about Garver’s Death.”

25 Ritter, letter of February 3, 1918.

26 Cablegrams 694-S and 936-R.

27 Harmon C. Rorison was commissioned as a first lieutenant on December 3, 1917; see Ancestry.com, North Carolina, World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919, record for Harmon Chadbourn Rorison.

28 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, [Outgoing], record for Harmon C Rorison.

29 “Lieut Rorison in France.”

30 See the “Chronology of Service” on p. 33 of Doyle’s “War Birds Pictorial.” The “History Sheet” does not give an end date for Rorison’s time at Turnberry.

31 Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 41.

32 Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 40.

33 Springs, diary entry for February 17, 1918, quoted on p. 90 of Springs, Letters from a War Bird; War Birds, entry for March 3, 1918.

34 See Hooper’s log book; Kissell, diary entries for February 12 and 14, 1918; Springs, diary entries for February 22 and 23, 1918, on p. 91 of Springs, Letters from a War Bird.

35 “History Sheet.”

36 Biddle, “Special Orders No. 83.”

37 For dates relating to Rorison’s R.A.F. service, see (in addition to the “History sheet” and the “Chronology of Service” on p. 33 of Doyle’s “War Birds Pictorial”) his R.A.F. casualty form: “Lieut. J C Rorison USAS.”

38 Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 419.

39 “24, 85 Squadrons – What Brigade/Wing.”

40 See quotation from Malcolm Charles McGregor on p. 54 of Cunningham’s Mac’s Memoirs, and Guy Maynard Baldwin’s account on p. 249 (56) of Munsell, “Air Service History.”

41 On Baker taking over from Bishop, see Cunningham, Mac’s Memoirs, p. 57.

42 On the paucity of records for 85, see Graeme’s and Henshaw’s posts on the second page of “85 Squadron – party-hearties?”

43 Cunningham, Mac’s Memoirs, p. 51. Baldwin recalled “two shows a day” (Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 249 [56]).

44 Munsell, “Air Service History,” pp. 258–59 (65–66).

45 See the tally for July 7, 1918, provided by Graeme in “85 Squadron aerial victories”; cf. the relevant entries in Shores, Franks, and Guest, Above the Trenches. On p. 131 of Great Britain, Royal Air Force, Royal Air Force Communiqués 1918, it is stated that “Maj. Edward Mannock . . . celebrated his promotion with a victory on 8 July,” and Longton’s victory, according to Shores et al., op. cit., was also credited in the R.A.F. communiqué of July 8, 1918. Shores et al., op. cit., p. 46, note that “The date given was often that after the action in respect of claims made in the late afternoon. No reliance can be placed upon the date in the Communiques being the correct date.”

46 See the transcription of Longton’s combat report on p. 210 of Springs, War Birds, ed. Hillier; where the map references indicate the vicinity of Merville.

47 Skelton, Callahan, the Last War Bird, p. 26. N.B.: Skelton’s reference to “3:30 p.m.” is presumably a typographical error for “8:30 p.m.” Skelton reproduces only the narrative of the combat report; I have not been able to find a copy of the full report; it is not in Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F.

48 See the relevant entries in Shores, Franks, and Guest, Above the Trenches.

49 See the tally for July 14, 1918, provided by Graeme in “85 Squadron aerial victories”; the combat reports of Mannock, Arthur Clunie Randall, Rorison, and Longton (but not Dixon) are transcribed on pp. 211–14 of Springs, War Birds, ed. Hillier.

50 Springs, War Birds, ed. Hillier, p. 213.

51 Munsell, “Air Service History,” pp. 259 (66).

52 Transcription in Springs, War Birds, ed. Hillier, p. 213.

53 Great Britain, Royal Air Force, Royal Air Force Communiqués 1918, p. 134.

54 His name does not appear, for example, in Victories and Casualties.

55 Springs, War Birds, ed. Hillier, p. 223; see op. cit., pp. xxiii and xxv on Randall as B flight leader and squadron C.O.

56 Rorison’s description in his account on p. 259 (66) of Munsell, “Air Service History.”

57 “History sheet.”

58 Combat report transcribed on p. 224 of Springs, War Birds, ed. Hillier.

59 The account in McGregor’s letter differs in a number of details from that in his combat report; he also in the letter writes that “we bagged three and the other squadron two, with the loss of only one man from the other squadron.” I find no record of an R.A.F. casualty that day, and no records of the other E.A. “bagged.”

60 On V Brigade and Fourth Army at this time, see Wise, Canadian Airmen and the First World War, p. 521.

61 “Captain D Carruthers 1/Can Div Supply Column.”

62 See the relevant entries in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II.

63 “Lieut. J C Rorison USAS.”

63a Illingworth, A History of 24 Squadron, p. 88.

64 This is in the War Birds entry for August 8, 1918; the narrative’s chronology is often unreliable, and Springs, by this time at the 148th Aero, was apparently unaware of Rorison and Carruthers’s detour through No. 84 Squadron. Carruthers was out of commission for a time with a septic hand and did not join No. 24 Squadron until after Rorison had left; see ““Captain D Carruthers 1/Can Div Supply Column.”

65 “100 years ago today – 8 September 1918”; and see relevant entries in Shores, Franks, and Guest, Above the Trenches.

65a Illingworth, A History of 24 Squadron, p. 47; p. 46.

66 “Lieut. J C Rorison USAS,”

67 “Attached to No. 56,” p. 320 (Winslow’s diary entry for September 13, 1918).

68 See chronology on p. 33 of Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial.”

69 Ibid.

70 “History of 25th Aero Squadron (Pursuit),” p. 2.

71 “History of 25th Aero Squadron, (Pursuit),” p. 5.

72 For Poler, see Sloan and Hocutt, “One of the ‘War Birds’,” p. 26; for Baldwin, see his letter to the Pennsyalvania War History Commission in Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917–1919, 1934–1948, record for Guy Maynard Baldwin. See also Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 379.

73 “History of 25th Aero Squadron, (Pursuit),” pp. 5–6.

74 War Department. Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list, Casuals – for duty, Olympic.

75 Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 53.

76 “In Memory,” Trinity Reporter.

77 Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925, record for John Chadbourn Rorison.

78 “Deaths and Funerals.”

79 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 195.