(Springfield, Missouri, November 16, 1895 – near Villers-Bretonneux, France, June 27, 1918).1

Flying Training ✯ France & No. 48 ✯ June 27, 1918 ✯ Afterwards

Goad was the only son (and only surviving child) of Springfield lawyers (his mother was admitted to the Missouri bar in 1892—according to her obituary, only the second woman to be admitted in Missouri).2

He attended Drury University in Springfield, graduating in 1916, and then began studying law at the University of Chicago.3 When he registered for the draft in June 1917, he was at a training camp at Fort Riley, Kansas. He attended ground school at the University of Illinois, graduating either August 25, 1917, or September 1, 1917; he appears in lists of graduates for both dates.4

Goad sailed with the 150 men of the “Italian” or “Second Oxford Detachment” to England on the Carmania. They departed New York on September 18, 1917, bound for Halifax, where they joined a convoy that set off across the Atlantic on September 21, 1917. When, after an uneventful crossing, they docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, they found that they would not go to Italy, but would remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. A month later, on November 3, 1917, most of the men, including Goad, departed for Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gun school at Harrowby Camp.

While fifty of the men at Grantham were sent on to flying schools on November 19, 1917, the rest, including Goad, continued their course at Harrowby Camp through the end of November. On November 29, 1917, they celebrated Thanksgiving in great style, with many of the men who were already at flying schools coming in to join them. Festivities included a football game between the “Unfits” and the “Hardly Ables.”5 Goad appears in photos of the players taken that day.

Flying Training: Elmswell, Stamford, Marske, Ayr

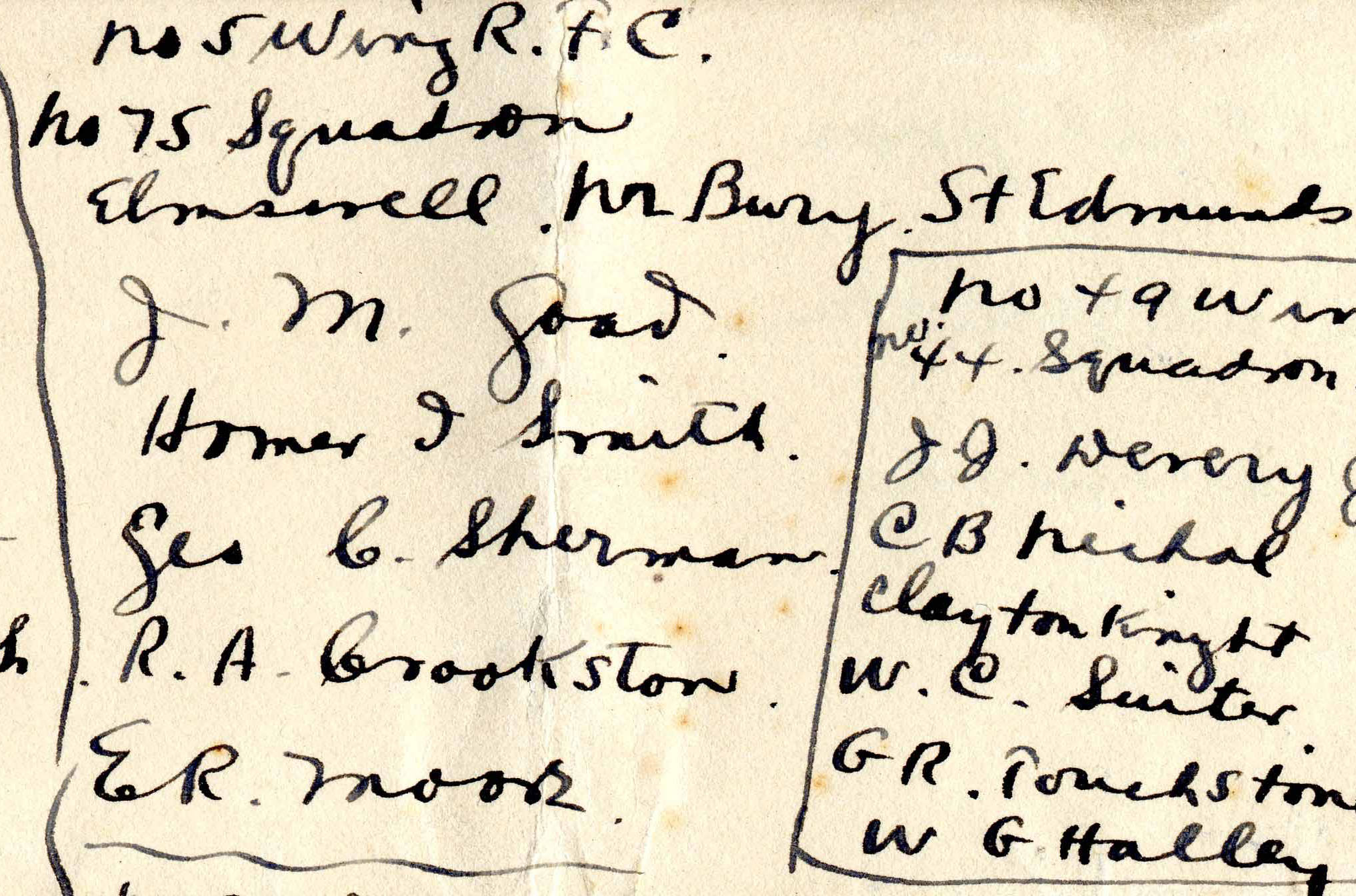

A few days later, on December 3, 1917, the remaining men at Grantham were posted to squadrons for flight training, and Goad was one of five men assigned to No. 75 Squadron in Elmswell in East Anglia.6 No. 75, a home defense squadron, was apparently flying F.E.2b’s at this time, two-seater planes used as night fighters; whether these were also used in elementary flight training, I have not been able to determine.7

After nearly two months at Elmswell, Goad was posted on January 26, 1918, to Stamford,8 almost certainly, like his fellow second Oxford detachment members John Warren Leach, Robert Thomas Palmer, and Pryor Richardson Perkins, to No. 5 Training Depot Squadron at Easton on the Hill about two miles south-southwest of Stamford (the second Oxford detachment members sent to Stamford in early November had been assigned to No. 1 T.D.S. about three miles to the east, near Wittering). At 5 T.D.S., Goad would have trained on B.E.2d’s and B.E.2e’s and then perhaps DH.6s. Once ready for operational planes, he may have flown R.E.8s and B.E.12s before trying out a DH.9. One of his flights in a DH.9 is documented. On March 17, 1918, Palmer noted in his log book that he was Goad’s passenger in DH.9 [C]6117 during a two hour flight, apparently part of a formation, flying at 10,000 feet, from Stamford to Grantham and back.8a

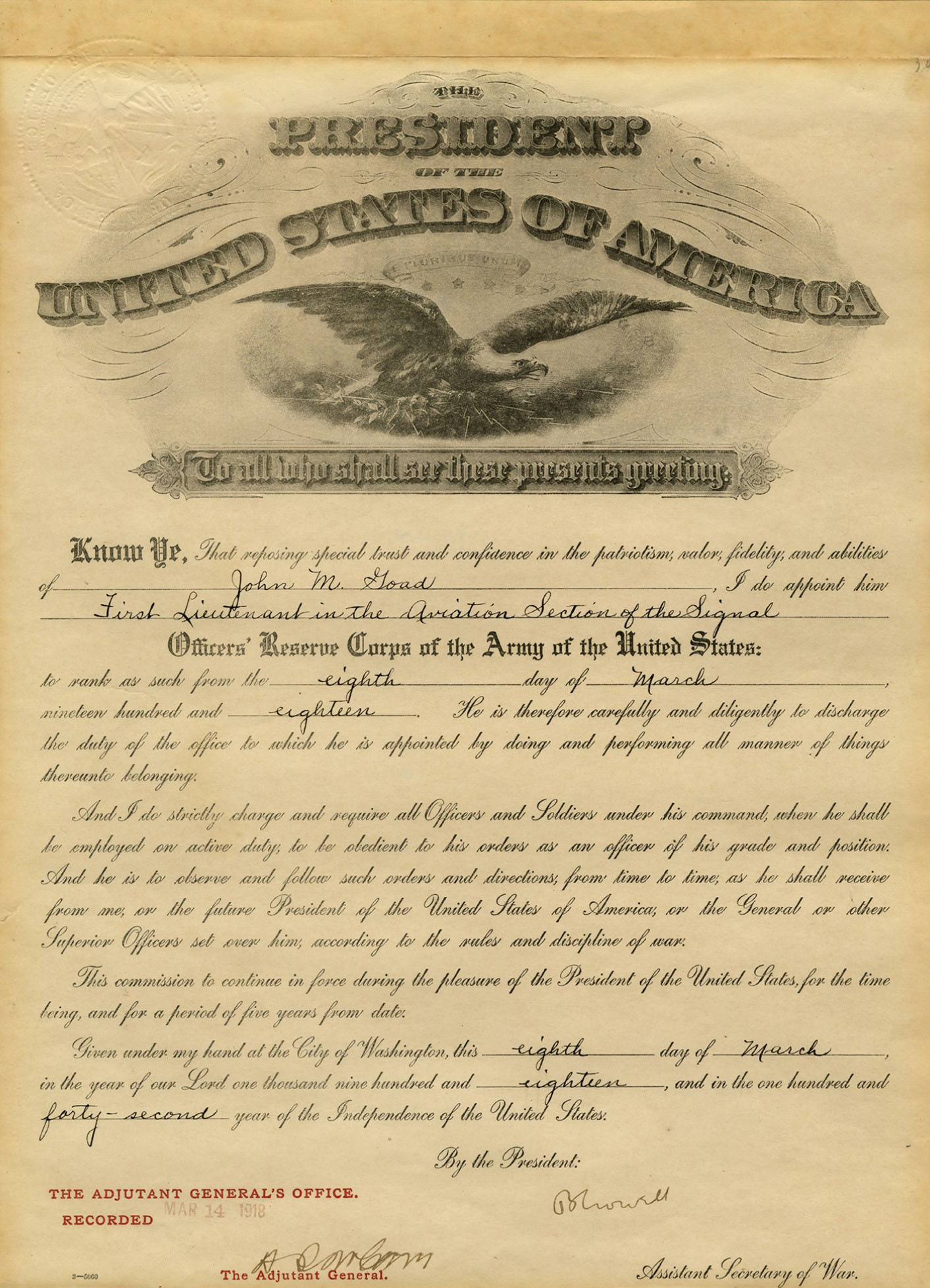

Meanwhile, by the end of February, Goad had advanced sufficiently to be recommended for his commission. Pershing’s cable forwarding the recommendation to Washington is dated February 26, 1918. Goad’s appointment letter, signed by the Assistant Secretary of War, Benedict Crowell, is dated March 8, 1918. The cable confirming the appointment is dated March 11, 1918.9 He was apparently still at Stamford when he was placed on active duty on March 23, 1918.9a

Goad’s R.A.F. service record is silent regarding his training and postings after Stamford, but he evidently trained at Marske and Ayr. Deetjen remarks in his diary entry for April 8, 1918, written at Marske, that “Sunday I went to the station to see Johnny Goad leave for Ayr.”

France & No. 48 Squadron R.A.F.

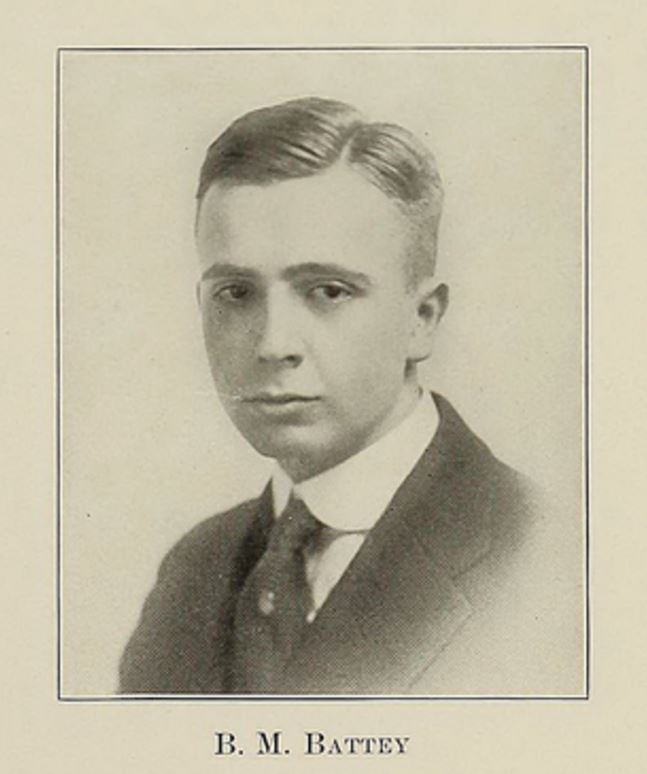

In Warren P. Munsell’s annotated list of American officers who served with the R.A.F. in the field, in his “Air Service History,” Goad is described as “posted to R.A.F. and to 48 R.A.F.” on May 24, 1918, followed the next day by Ervin David “Molly” Shaw of the second Oxford detachment, and the day after that by Bryan Mann Battey, an American who had trained in Canada.10 However, pictures in a photo album kept by John Chadbourn Rorison put Goad at the pilots pool at Rang-du-Fliers, France, sometime during the period June 8–14, 1918, and Battey, writing in July 1918, recollected “Molly arriving just a few days later than I. Within a week we were joined by John Good [sic].”11 Recently digitized “casualty forms” of R.A.F. officers record that Goad was posted to 2 A.S.D., which included the pilots pool at Rang-du-Fliers south of Boulogne, on May 26, 1918, and not until June 15, 1918, to No. 48.12 On that day the Canadian officers and the three American officers of the squadron posed for a photo; a copy was kept by Canadian Harry Yarwood Lewis.

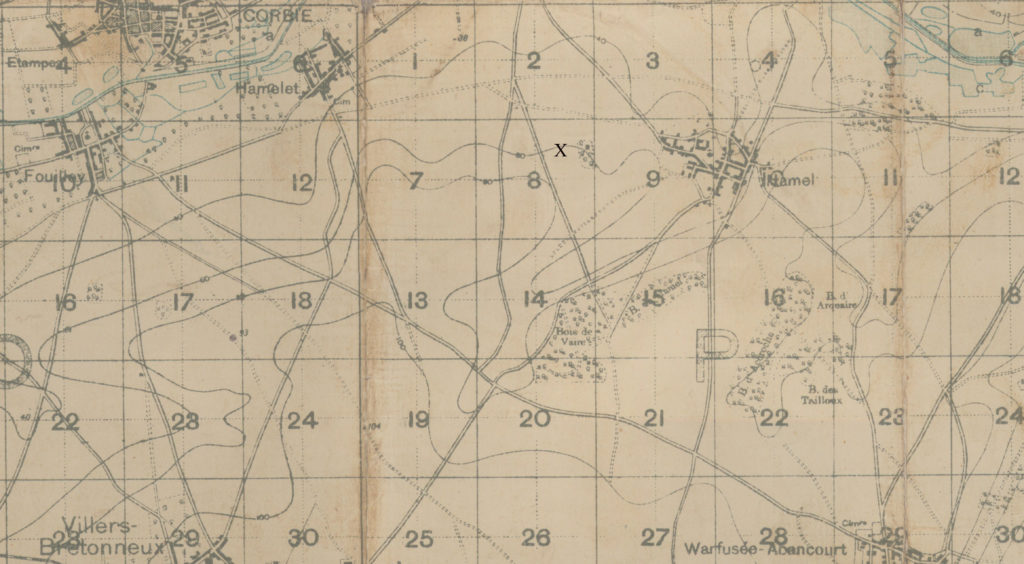

No. 48 Squadron R.A.F., stationed at Bertangles, was flying Bristol Fighters (two-seater reconnaissance and fighter planes) and was involved in offensive patrols and reconnaissance, as well as ground strafing and bombing. As part of the 22nd Wing, 48 was supporting the British Fourth Army, whose front extended approximately from Albert to Montdidier.13

According to Battey, he, Goad, and Shaw were the only “Yanks” in the squadron. The three Americans formed their own “aerial circus that made our English fellows sit up and take notice. In very short order we were generally known as ‘the wild Yanks.’ One of us that might be left upon the ground could always recognize the other ‘wild Yanks’ long before they slipped down into the drome by a series of tricks that we always indulged in before landing, partly to put America ‘on the map’ in our aerial sector and partly for the practice such stunts afford for real combat work.”14

Given that neither Goad’s log book nor relevant records from No. 48 Squadron are extant, it is not possible to say when he made his first foray into enemy territory. But the log book of Leonard James indicates that on June 24, 1918, a scant nine days after his arrival at No. 48, Goad, with James as gunlayer/observer, crossed the lines flying Bristol F.2b [C]962 at 7000 feet on an uneventful hour-long offensive patrol from Villers-Bretonneux to Montdidier.15 According to a letter Goad wrote on June 26, 1918, he was to have gone on a patrol very early that morning, but his “engine was not working right, so he did not go over the German lines but waited around for the others to return before landing.”16

June 27, 1918

Of Goad’s flight the next day, June 27, 1918, Battey noted that it “was his [Goad’s] first ‘show’ over the line,” meaning the first time Goad was involved in combat.17 B and C flights set out together in the afternoon. The squadron had learned that Jagdgeschwader II, whose Jagdstaffeln were gradually being equipped with the new Fokker DVIIs, had relocated to an aerodrome near Péronne and was now supporting the Second German Army, opposite the British Fourth Army and thus the 22nd Wing and No. 48 Squadron. It was deemed prudent to fly offensive patrols made up of at least two flights.17a

Battey describes the events of that day:

John and I were in the same flight and as the youngest members here in point of military seniority, we were assigned to the two rear places in “C” flight formation, the hottest position always in a scrap for an attack is always directed at the rear of a formation for many tactical reasons.

We had gained our altitude for crossing the lines by flying out to the channel and back. Climbing steadily, we had reached an altitude of 20,000 feet, our usual height for crossing the lines. It was a glorious day. The sky was cloudless. At our height we could see the broad sparkle of the channel as we crossed the lines and the channel was 25 miles away.

We had gone over about five miles and were reconnoitering southward when suddenly an observer in one of the forward machines sent up a red Veery [sic] light signal indicating attack of hostile aircraft.

Slowly our formation closed up until the machines were flying almost wing-tip and wing-tip. Behind us there were five German scout machines, two Pfalz’s and three Fokker’s. Both types being considerably faster than our machines, we were at a disadvantage.

All we could do was to draw them on until they were within fighting range then turn suddenly on them. The German tracer bullets were beginning to fly all around us, leaving the air full of feathery smoke trails. I recall distinctly seeing John return the signal of my gunner, who waved a friendly battle sign to our companion machine. I remember that John’s machine was holding its place in perfect formation with the flight, too perfect. I wanted to call to him to throw his machine around more—he was flying too straight—but the roar of the engines and the wind made mine a vain wish. His observer was firing and John was keeping the machine still for him. His was the first machine to open fire, and it drew the fire of the enemy.

There was a sudden burst of flame and the machine slowly rolled over on its top and started upside down. A few seconds later I caught sight of it again some thousand feet below, a blazing star falling.18

The relevant entry in Henshaw’s The Sky Their Battlefield II provides further details. The offensive patrol had left at 4:30 p.m. with Goad flying Bristol F.2b C877. The combat took place over Villers-Bretonneux (about ten miles east of Amiens, and only about twelve miles from Bertangles). One contemporary document notes that Goad’s plane “was observed falling in flames” and another that Goad was “seen to jump out of his machine.”19 Henshaw adds that Lieutenant Ulrich Neckel claimed to have shot down a Bristol Fighter over Villers-Bretonneux at 6:05 p.m., implicitly C877.20

The July 7, 1918, entry in War Birds includes the remark: “John Goad is dead. He was shot down in flames flying a Bristol Fighter. When the flames got too hot he turned the machine upside down and jumped.”

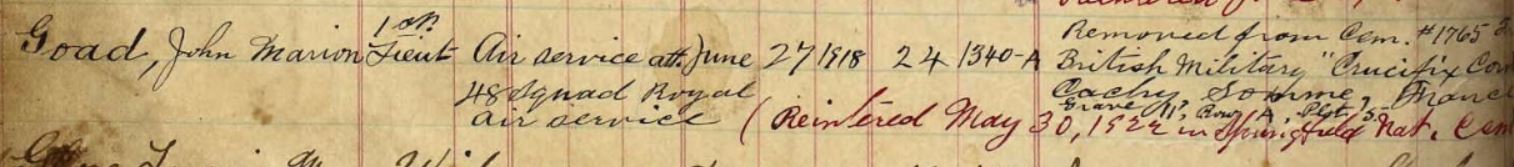

Afterwards

It was a month before Goad’s parents received word that their son was missing in action.21 Two days later (July 29, 1918) they learned some details, including that “Lieut Swyer [sic; sc. Dwyer], 35 Eaton Place, has been advised in a letter from Lieut. Paul S. Winslow, (U. S. Air Service) that Lieut. Goad was shot down in flames from a height of 21000 feet. Lieut. Winslow’s report, while unofficial, is no doubt reliable as he was serving at [sic] or near Lieut. Goad at the time of the accident.”22 Winslow was at the Rang-du-Fliers pilots pool on the coast awaiting assignment and presumably learned the news through the R.A.F. grapevine (it is unlikely that he “was flying nearby when the plane caught afire,” as Goad’s hometown newspaper reported).23

Goad’s father, George W. Goad, received two further communications, both from Keith Rodney Park, the C.O. of No. 48 Squadron, with information suggesting Goad might have survived the combat. Two Bristol Fighters from No. 48 had been shot down in flames in the same skirmish; it was thought that in one case the pilot regained control and might have landed safely. When it was determined that the pilot and the observer of the second plane (Edward Alec Foord and Leonard James in C935) had been killed in action, Park, writing September 2, 1918, held out the hope that “Bristol No. C877 piloted by your son, was the machine seen by the infantry of our front line, to apparently make a normal landing behind lines.”24 In June of the following year, however, Goad’s parents learned that Goad had been officially declared killed in action.25

Attention was now turned to trying to locate Goad’s body. Because Goad was an American serving with the R.A.F., two bureaucracies had the responsibility to try to locate his remains: the British Imperial War Graves Commission and the American Graves Registration Service, part of the American Army Quartermaster Corps. Additionally, Goad’s father, like Herbert Hooper, father of another missing pilot, made his own inquiries, writing a letter to “Chief City Officer” of Maricourt with details of Goad’s last flight and hoping that “perhaps you might place this information in the hands of some person, newspaper or organisation that could in some way get me definite information or furnish some clue that would lead to further information. He was our only child. You will appreciate our anxiety.”26 This request apparently yielded no results, and on September 17, 1920, the senior Goad received a letter from the Cemeterial Division of the Quartermaster General indicating that neither the G.R.S. nor the I.W.G.C. had succeeded in locating his son’s grave.27

It came as a bolt from the blue, then, when George W. Goad received a telegram on April 18, 1922, informing him that his son’s body was due to arrive in Brooklyn in a few days. He immediately requested an explanation of this change in the state of affairs.28 In fact, efforts to locate the body of John M. Goad had continued, although Mr. Goad had evidently not been kept adequately informed—only approached for additional information and records.

In early October 1920 the G.R.S. received a letter from the I.W.G.C. informing them that “during the course of the exhumation and search for isolated graves, the grave of an unknown American Flying Officer was found at a point map reference 62d.P.8.b.5.5, and has been removed to Crucifix Corner British Cemetery. . . . It is thought that this might possibly be the grave of 1st Lieut. J. M. Goad.”29

By April 27, 1921, Thomas G. Hanson of the Quartermaster Corps was prepared to say that “it is the opinion of this office that the body of Lieutenant Goad is contained in Grave #4, Row A, Plot #5 , British Military Cemetery #1765, Cachy, (Somme). However,” he continues, “report of disinterment and reburial does not furnish sufficient information to positively identify remains.”32 He requested that the watch mentioned in the second exhumation report be compared with the photostat, supplied by George W. Goad, of an advertisement for a watch John M. Goad was known to have worn. All efforts to locate the watch again were in vain.

In early October 1921 Charles J. Wynne of the Quartermaster Corps was in essentially the same position that Hanson had been in in the spring. But he made the decision to declare the remains in question to be those of Goad; indeed, already in September preparations were underway to ship the body to Goad’s father.33

A letter from George H. Penrose dated May 2, 1922, to George W. Goad in response to his request for an explanation of the startling telegram of April 18, 1922, summarizes the circumstantial evidence: “Considering the fact that this body was discovered in the location where Lieutenant Goad was shot down in 1918 and also due to the fact that it was apparent that this officer was an American attached to the Royal Air Force and there being no other bodies of aviators found in this immediate locality, identification is positive in the firm belief of this office. The body description, of course, is not as complete as would be desired, but the hair checks in that the reports show that the same was dark brown and very thick. Every possibility of other bodies being newly discovered in this locality has to the best knowledge of this office been eliminated. . . .”34

In response, Goad thanked Penrose and wrote that “I now feel reasonably certain that the body at Brooklyn referred to in your communication is the body of my son. . . .” He had decided that his son should be buried in the National Cemetery in Springfield, and noted that the American Legion Post at Springfield, named for John Marion Goad, desired that the funeral be held on Decoration Day, May 30, 1922; the shipment of the body should be timed accordingly.35

The body of Goad’s gunner/observer, Sergeant Cyril Norton, was not found. He is commemorated at The Arras Flying Services Memorial in the Faubourg-D´Amiens Cemetery, Arras. The entry for him in the memorial register indicates he was eighteen years old, the son of Tom and Nellie Norton of Birmingham.36

mrsmcq August 19, 2017

revised February 15, 2019, to reflect Goad’s casualty form; July 20, 2021, to reflect entry in Palmer’s log book

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Goad’s date and place of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for John Marion Goad. The photo, probably taken soon after Goad received his commission, is reproduced with the kind permission of American Legion Goad-Ballinger Post 69, at Springfield, Missouri, who have the original. It has been slightly cropped. My thanks to Local History Reference Associate Michael Price at the Springfield-Greene County Library in Springfield Missouri for his assistance in finding materials related to Goad.

2 See the obituary for Minnie Goad in “Deaths in Missouri.” Young, “Ernestine Goad,” provides evidence of Goad’s sister, who died before he was born.

3 See The University of Chicago, Annual Register Covering the Academic Year Ending June 30, 1917, p. 701.

4 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917]” and “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

5 Chalaire, “Thanksgiving Day with the Aviators Abroad.”

6 Foss, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” (in Foss, Papers).

7 Accounts of the operational planes used by No. 75 Squadron differ; I rely here on Barrass, “No 71 – 75 Squadron Histories.”

8 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for John M. Goad.

8a The relevant entry for this plane in Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File, puts C6117 at 5 T.D.S. at this time, which corroborates Goad’s having been posted to 5 T.D.S.

9 See cablegram 652-S and 900-R (p. 3). The appointment letter is part of the “Goad-Ballinger World War I Collection.”

9a Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

10 See Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 231 (38) for Goad, p. 226 (34) for Battey (listed by Munsell as D. M. Batty), and p. 241 (48) for Shaw. On Battey’s training, see Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 223, where he appears as Byron M. Batty.

11 Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 43; Battey’s letter cited in “Lieuts. Purdy and Shaw.”

12 “Lieut. John Marion Goad U.S.A.S.” It should perhaps be noted here that most of 48 Squadron’s own records were destroyed in a night raid on the Bertangles aerodrome on August 24, 1918. On this raid, see Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 480, and Robertson, “No. 48 (General Reconnaissance) Squadron.”

13 Wikipedia, “No. 48 Squadron RAF.”; Bailey and Chamberlain, “No. 48 Squadron RFC/RAF,” pp. 118–20.

14 Battey, in a letter quoted in “Body of Lieut. John M. Goad Found.”

15 I thank Merve Goddard for supplying a copy of the relevant page of Leonard James’s log book.

16 Goad’s letter is paraphrased in “Springfield Flier Falls 21,000 Feet Behind Lines, His Machine in Flames.”

17 From Battey’s letter cited in “Lieuts. Purdy and Shaw.”

17a Stewart K. Taylor, “Uncompromising and Efficient,” pt. 1, pp. 197–198.

18 Continuation of Battey’s letter quoted in “Body of Lieut. John M. Goad Found” (continuation p. 10).

19 From the relevant page in The National Archives (UK), Reports on aeroplane and personnel casualties, record for 21 June 1918 – 30 June 1918 (I am grateful to Andrew Pentland for a copy of this report), and from the witness account submitted by L. A. Harradence in The National Archives (UK), Record of certain R.F.C., R.N.A.S. and R.A.F. war casualties (I am grateful to a Great War Forum member for a copy of this report). It should be noted that two of the four casualty cards for J. M. Goad that can be seen at the RAF Museum London erroneously place Goad at No. 49 Squadron; see, for example, “Goad, J.M. (John M.).”

20 See also Franks, Bailey, and Duiven, The Jasta War Chronology, pp. 195-96, who note Bristol F.2b claims by four different German pilots around this time, and two relevant casualties: Goad’s C877, and C935, flown by Edward Alec Foord, also of No. 48. Combat victory attribution is uncertain, but Henshaw’s more recent work probably represents the most accurate possible updating of Franks, Bailey, and Duiven’s 1998 work. See also the discussion on pp. 120-22 of Bailey and Chamberlain’s “No. 48 Squadron, RFC/RAF.” Neckel is generally associated with Jasta 12. However, information about Jasta 12 on pp. 39–40, 48–49, and 51–52 of Möller, Kampf und Sieg, an account of Jagdgeschwader II written in 1939, indicates that, with some exceptions (see, for example, the mention, p. 43, of [Hugo] Schulz of Jasta 12 on June 12, 1918), Jasta 12 did not have flight worthy aircraft from late May through mid-July 1918 and could not take part in missions. However, Möller also mentions (see pp. 46, 47, and 50) combat victories by Neckel during June 1918, implicitly while flying with Jasta 13, and, in connection with Neckel’s “Pour le mérite” (p. 110), indicates Neckel was with “Jasta 12, 13, 12.” On p. 65, describing events of August 1, 1918, Möller makes it clear that Neckel was (once again?) with Jasta 12. More recently (2004), Schmeelke, Das Kriegstagebuch der Jagdstaffel 12, states, p. 82, that on May 18, 1918, Neckel had to (“musste”) switch to Jasta 13, and later mentions, p. 89, in connection with events of August 11, 1918, that Neckel had returned to Jasta 12. Writing about Neckel in 2006, Guttman (“Leader from the Ranks”) states that “Neckel was transferred to neighboring Jasta 13 . . . on May 30 [1918].” See Schmeelke’s introduction (p. 5) regarding primary sources for the study of Jasta 12 and other Jagdstaffeln; also p. 61 regarding material missing for January through July 1918. Neither Schmeelke nor Guttman give a specific source for their respective dates for Neckel’s assignment to Jasta 13. I was prompted to wonder which Jasta Neckel was flying with on June 27, 1918, when Goad was shot down, because I wondered what kind of plane Goad had encountered. Assuming Neckel was with Jasta 13, he would have been flying one of the new Fokker DVIIs. Goad would thus have encountered an experienced pilot in a formidable aircraft. [Note updated January 5, 2024, with information on Neckel.]

21 See the “abstract of reports” compiled by Goad’s father, George W. Goad, included in Goad, World War One Burial File (images 139 and 140), and “Lieut. John M. Goad is Reported as Missing.”

22 This is George W. Goad’s transcription in the above-mentioned “abstracts of reports” of a letter to him dated July 2, 1918, from the C.O. of No. 48 Squadron, Keith Rodney Park.

23 On Winslow, see Revell, High in the Empty Blue, p. 319. For the newspaper report, see “Springfield Flier Falls 21,000 Feet Behind Lines, His Machine in Flames.”

24 See “abstract of reports” from Goad, World War One Burial File, cited in earlier note, and “Airman May have Alighted Safely.”

25 “Notified of Death.”

26 Goad, World War One Burial File, image 146.

27 Memo dated September 17, 1920, from Charles C. Pierce to G. W. Goad, in Goad, World War One Burial File, image 109.

28 See Goad’s telegram of April 19, 1922, and his letter of August 25, 1922, in Goad, World War One Burial File, image 17, and images 72-74.

29 Goad, World War One Burial File, image 105.

30 Goad, World War One Burial File, image 7.

31 These reports are images 8–11 in Goad, World War One Burial File.

32 Goad, World War One Burial File, image 95.

33 Goad, World War One Burial File, images 85 (Wynne) and 29 (preparations to ship body).

34 Goad, World War One Burial File, images 68–69.

35 Goad, World War One Burial File, image 61. The post was chartered in 1919 as the John Marion Goad Post; by 1920 it had been renamed the Goad-Ballinger Post, honoring also Missouri native Homer Jerome Ballinger.

36 See “Norton, Cyril.”