(Tuscaloosa, Alabama, July 17, 1893 – New Orleans, Louisiana, January 31, 1954).1

Flying training in England ✯ With No. 206 Squadron R.A.F. ✯ In hospital and afterwards

One of Leach’s ancestors on his father’s side was Mayflower passenger Peter Brown. Several generations of the family resided in Massachusetts, but some descendants resettled in New York, where Leach’s grandfather, Sewall Jones Leach, Sr., was born. A man of many parts, he moved in 1837 to Alabama, settling in Tuscaloosa in 1842; “although a northerner by birth, [he] was a man of strong southern feeling.”2 Leach’s maternal grandfather, born in England, came with his father and family at a young age to Tuscaloosa. Said father, James William Warren, became a newspaper editor and printer, and his son, John Frederick Warren, followed in his footsteps.3 The latter’s daughter, Kate Brantley Warren, married Sewall Jones Leach, Jr., in 1880, and they had a large family. John Warren Leach was their second youngest child.

Leach excelled in sports in high school in Tuscaloosa and at Alabama Presbyterian College in Anniston, which he attended for a time before enrolling briefly at the University of Alabama.4 I find no record of a college degree, but his course of study is suggested by his being described as a civil engineer in a 1916 Tuscaloosa directory.5 When he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, Leach gave his occupation as “bookkeeper” and indicated that he was working for his father.

Not long afterwards he signed up for the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and attended ground school at the University of Illinois’s School of Military Aeronautics in Champaign.6 His name does not appear in any of the ground school graduation lists, but he presumably was with either the class that graduated August 25, 1917, or the one that graduated September 1, 1917.

Many of the men from these two classes, including Leach, chose or were chosen to continue training in Italy, and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “Second Oxford Detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. The ship left New York on September 18, 1917, and, after a stopover in Halifax, set out as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. Leach later wrote his parents about the “wonderful experiences enroute across the Atlantic,” apparently not alluding to the discomforts of the voyage.7 On September 24, 1917, according to War Birds, “Quite a sea has been running to-day, or so it seems to me, and several of the boys have been sick. Especially Leach from Tuscaloosa, who is awfully low. They put a sign on him as he lay in his chair on the deck: ‘I want peace and quiet’.”

The Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, and the men learned that they were not to go to Italy after all, but to train with the Royal Flying Corps in England. They attended ground school (again) at the R.F.C.’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. There Leach was able to room with men he knew from Illinois’s School of Military Aeronautics: Walter Ferguson Halley, George Orrin Middleditch, and Chester Albert Pudrith.7a

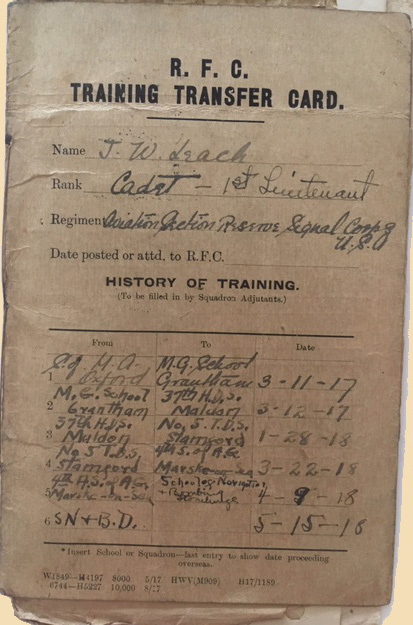

A month after arriving at Oxford, on November 3, 1917, Leach, along with most of the rest of the detachment, left for machine gun school at Harrowby Camp, near Grantham, in Lincolnshire. They spent their first two weeks learning to operate the Vickers machine gun and then moved on to the Lewis (in the latter course Leach was marked “Excellent”).8 During free time they could explore the rural countryside or the nearest metropolis, Nottingham, twenty miles to the west. The War Birds entry for November 6, 1917, reads in part: “Cal [Callahan], Schlotzhauer, Leach and I went over to Nottingham Sunday and had supper. Believe me, it is some town,” and the entry for Nov 13, 1917: “Jack Fulford, Cal, Morrison, Leach and I went to Nottingham over the week-end. We didn’t get very drunk.”

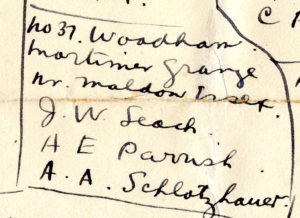

On November 19, 1918, fifty men for whom places had been found at flying schools left Grantham, but Leach was not among them and thus remained at Grantham through November. Finally, on December 3, 1917, the remaining men were posted to flying squadrons. Leach, Albert Elliott Parrish, and Harry Adam Schlotzhauer, all of whom had been at the University of Illinois ground school, were posted to “No. 37 Woodham Mortimer Grange nr. Maldon Essex.”9

Flying training in England

No. 37 Squadron R.A.F., commanded by Frederick William Honnet, was a home defense squadron charged with defending London against German air attacks from the east. Its headquarters was at The Grange, just west of the small village of Woodham Mortimer in Essex, and its three flights were based at nearby Stow Maries and Goldhanger. The squadron had on hand B.E.12s, single-seat aircraft designed for reconnaissance and bombing, as well as B.E.2d’s and B.E.2e’s, two-seat biplanes that had been used operationally through early 1917 for the same purposes, but which now served mainly as training aircraft.10

On December 4, 1917, the day after his arrival at No. 37, Leach went up for his first flight, 25 minutes at 1000 feet, for “pleasure,” with “Capt. Sowry” piloting the B.E.2e.11 By the end of 1917, Leach had been up fourteen times with various pilots from No. 37, for a total of eight hours and fifteen minutes, and had practiced landings. On January 2, 1918, he was ready to fly solo in a B.E.2e, and he went up solo many times over the next days, flying, apparently, sometimes out of Goldhanger, sometimes out of Stow Maries. He completed his work at No. 37 on January 26, 1918, with about thirty hours flying time under his belt, over twenty of it solo, presumably prompting his C.O. to forward a recommendation for his commission.12 Leach’s longest flight, in B.E.2e [B]4457, was cross country and lasted a little over three and a half hours, some of it at 9,000 feet.13 This presumably meant he had now passed the cross-country and perhaps also the height test required for graduation from the first stage of R.F.C. training.

On January 28, 1918, Leach was posted to No. 5 Training Depot Station near Stamford where a number of second Oxford detachment members were also training. He initially continued flying B.E.2s, notably on February 11, 1918, when he took up fellow detachment member Julian Carr Stanley and wrote in his log book “Jake Stanley 1st Pass[enger]!”

The next day, February 12, 1918, a recommendation that “John W. Leach” be commissioned a first lieutenant was forwarded to Washington in a cable signed by Pershing. Leach was one of the first of the cadets of the second Oxford detachment to be recommended for a commission. The confirming cable was dated February 20, 1918. There are some discrepancies among the relevant documents as to when Leach was placed on active duty, but at least by March 11, 1918.14

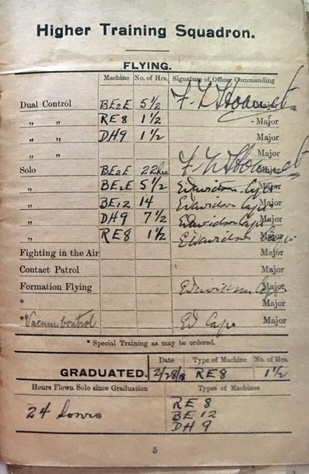

Meanwhile, on February 18, 1918, Leach went up for the first time in a B.E.12 (twice) and an R.E.8. The former was basically a single-seat version of the B.E.2, the latter a two-seat plane; both were intended for reconnaissance and bombing. Leach’s initial flights in the R.E.8 were dual, but he went up solo on February 27, 1918, thus fulfilling the R.F.C. graduation requirement that he have “flown a service machine satisfactorily.”15 He noted in his log book that as of March 1, 1918, he had flown a total of thirty-five hours and fifteen minutes solo.

A week later, on March 8, 1918, Leach flew for the first time in a D.H.9, the type of plane he would fly in France. This first flight was a brief “joy ride” with someone else apparently piloting. By mid-March he was piloting a D.H.9 himself and beginning to practice formation flying. He made his last flights at 5 T.D.S. on March 21, 1918, in a D.H.4 and an R.E.8 and was assigned the next day to No. 4 Auxiliary School of Aerial Gunnery at Marske-on-Sea in Yorkshire.

There is a gap in Leach’s flight log between March 21 and April 1, 1918, probably reflecting ground course work. His fellow second Oxford detachment member William Ludwig Deetjen, who arrived at Marske around the same time, wrote that “The course consists of a week of ground work, on C.C. Gear [Constantinesco-Colley synchronization gear] and Vickers guns. First theory, then stoppage and deflection practice on the range. . . . Then later we do aerial firing on Bristol fighters.” (Deetjen also noted that “we are about 400 yards from the sea, and the bracing air and sunshine make us sleep and eat more than ever.”16) Leach’s first flight at Marske (on April 1, 1918, the day the R.F.C. became the R.A.F.) was in a DH.4, but that same day he also flew a Bristol Fighter with an instructor. The next day he flew a Bristol Fighter solo. Leach’s time at Marske was brief. On April 9, 1918, he was posted to the School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping at Stonehenge and was thus obliged to make the considerable journey from the north of Yorkshire south to Wiltshire.

Initially at the S.N. & B.D. Leach was back flying B.E.2e’s, practicing formation and cloud flying, and bombing; he also now took up other men who served as observers. Towards the end of the month of April and into May he flew DH.9s and, in addition to formation and cloud flying, practiced aerial fighting. By the end of his training on May 14, 1918, he had flown twenty-nine hours and forty minutes solo on DH.9s, and ninety-three hours and forty minutes solo on all types of machines. The comment on his work at Stonehenge reads “Has passed an extremely good course & should prove very useful airman.”17

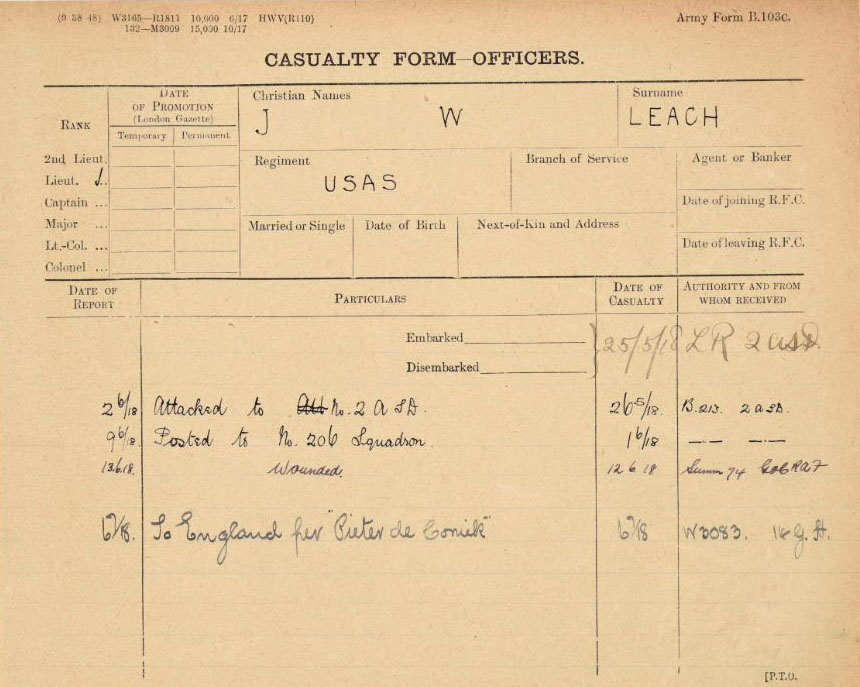

Leach probably had some leave coming to him; in any case, he records no flying for a week. He evidently spent some of this period in London; Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, who was working at American Aviation HQ in London, noted in his diary lunching with Leach and others on May 19, 1918. Like many of the men who had finished training but were not yet posted, Leach was briefly assigned ferry pilot duties. His log book records his flying a DH.4 from Farnborough to Hounslow, a distance of about twenty miles. He may have taken the opportunity to sightsee, as he records a flight time of seventy-five minutes. This, apparently his only flight as a ferry pilot, took place on May 22, 1918. Three days later (May 25, 1918), Milnor recorded in his diary that his good friend Hugh Douglas Stier was setting off that day for France along with Harold Hatch Gile of the first Oxford detachment, and Schlotzhauer and Leach of the second; they were initially assigned to the pilots pool at No. 2 A.S.D. (Aeroplane Supply Depot) south of Boulogne.18

With No. 206 Squadron R.A.F.

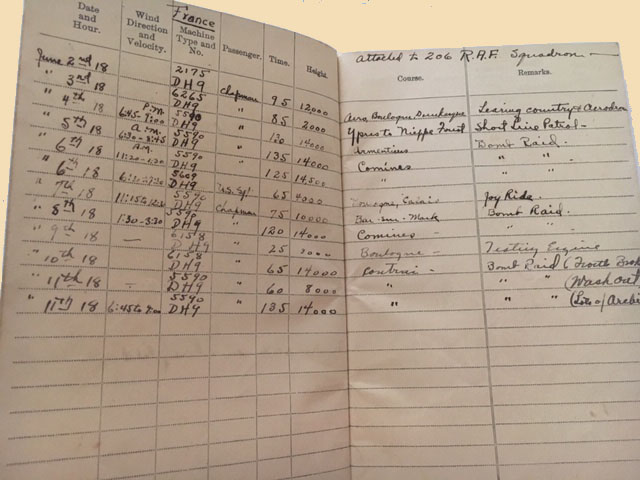

Leach’s wait there was comparatively short. On June 1, 1918, he was assigned to No. 206 Squadron R.A.F., a DH.9 squadron, which was stationed, briefly, at Boisdinghem, before it moved a few miles west to Alquines on June 5, 1918. Schlotzhauer had been assigned to the squadron a few days previously; Stier would arrive a few days later.19 In a letter home, Leach remarked that “my room-mate of the past ten months [presumably Schlotzhauer] is still with me, also another American [presumably Stier], and the three of us get along O.K.”20

No. 206 Squadron was part of the R.A.F.’s 11th Wing, which was flying on the British 2nd Army front in northern France and Flanders. John Stephen Blanford, an observer with 206 who arrived a day or two before Leach, describes the squadron’s area of responsibility: “our sector of operations, which was in fact the 2nd Army Front, ran from Houthulst Forest, 10 miles north of Ypres down as far as Nieppe Forest, 20 miles SW of [Ypres]—roughly 30 miles in all.” He notes that the war on the ground at this period was relatively quiet. “In the air, however, there was still no lack of activity, and all 11 Wing squadrons were in the air whenever the weather permitted flying.” Enemy aircraft seldom entered Allied territory, so “all our encounters with the enemy took place over their territory.”21 The squadron was tasked with tactical bombing, reconnaissance, and photography.

It has been stated by American historians of American pilots with the R.A.F. that R.A.F. regulations required new pilots to take two to three weeks to familiarize themselves with their squadron, their planes, and the territory before crossing the lines.22 The regulations were evidently not in force at 206. Observer Blanford accompanied his pilot, Francis Turretin Heron, on a combat mission on May 31, 1918, nine days after the latter reported for duty. Heron had taken Blanford up on an orientation flight the previous day: “After this somewhat sketchy initiation, we were deemed ready for combat, faute de mieux, for A Flight needed us to bring them up to strength.”23 C flight, to which Leach was assigned, was evidently also in need of men. Leach flew for ninety-five minutes on June 2, 1918, “Learning country & Aerodrome,” and the next day he flew a “short line patrol” from Ypres to Nieppe Forest. Then, on June 4, 1918, in the evening, just three days after his arrival, flying DH.9 [D]5590, he took part in a bomb raid at 14,000 feet over Armentières, which city had been inside German territory since being captured during the Battle of the Lys in April 1918. In his letter home a few days later, Leach wrote that “My first trip over I had holes shot through my tail plane and one through the body, about two feet from my head.”24

On June 5 and 6, 1918, Leach flew on two more bombing raids, this time targeting Comines, a few miles to the northeast of Armentières. According to Blanford, the road and rail bridges over the River Lys at Comines were the focus of a number of raids by 206 during this period.25

The evening of June 6, 1918, Leach flew [D]5609 on a “joy ride” to Boulogne and Calais; his crew this time was a “U.S. Sgt.,” presumably a mechanic in training. In his letter home from around this time Leach wrote that, in addition to his roommates, “There are several other U.S. officers over here training their mechanics. They with our crowd form a congenial bunch.”26

On all his flights with 206 other than the joy ride to the coast, Leach’s observer and gunner was the Englishman James Chapman, of whom he wrote that “I have a fine observer and gunner.”27 The two of them, flying [D]5590, took part the next day (June 7, 1918) in a bomb raid on Bac Saint Maur, about four miles west-southwest of Armentières. The DH.9s of 206 Squadron evidently met with resistance. Leach writes, probably referring to this raid, that “We were attacked by fourteen Huns and we brought down two.”28 An enemy aircraft is recorded as driven down out of control at 11:50 on June 7, 1918, over Bac Saint Maur by two pilot-observer teams from 206, and a few minutes later, Leach’s flight commander, George Leslie Eugene Stevens and his observer along with another team brought a Fokker DrI down at the same spot.29

On June 8, 1918, in the early afternoon, Leach again piloted [D]5590 on another bombing raid on Comines that lasted two hours. In his letter home that day he wrote that “All our machines are safe, and have been on all my trips,” a statement borne out by entries for this period in Trevor Henshaw’s The Sky Their Battlefield II and worth noting, given the inadequacies of the DH.9 and the squadron’s encounters with what were almost certainly better performing enemy aircraft. Leach also wrote, without mentioning a date, that “I claim part of one [enemy aircraft downed], as another pilot and I were shooting at this one Hun when he went down in flames”; he again refers to having “one [Hun] to my credit” in a later letter.30 Unfortunately the surviving documentation of No. 206 Squadron is limited and further information is not available. In passing I note how the mystique of aerial fighting colors Leach’s letter, despite his being with a bombing and reconnaissance squadron.

The next day, June 9, 1918, Leach tested the engine on DH.9 [C]6158 by flying to Boulogne and was apparently satisfied, for he and Chapman set out in it again the next day on a raid on Courtrai, farther east than Comines. They evidently had to return early; Leach’s log book records a flight time of only sixty-five minutes, and his notes indicate that something had broken. On June 11, 1918, he and Chapman were once again in [D]5590. One raid (whose start and end times are not indicated in his log book) was a “wash out,” but they set out again at 6:45 (presumably in the evening) on what must have been a successful bombing raid over Courtrai. Leach records flying at 14,000 feet and a flight time of two hours and fifteen minutes. In his notes he remarks: “lots of Archie” (anti-aircraft fire).

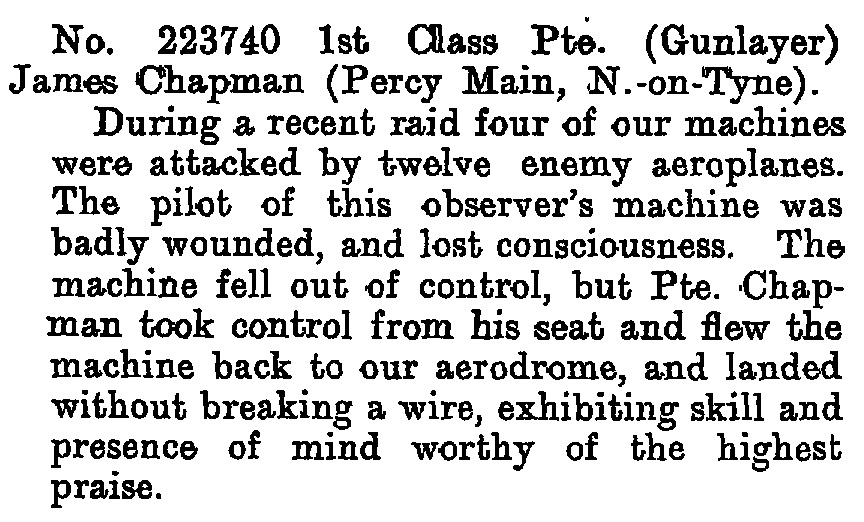

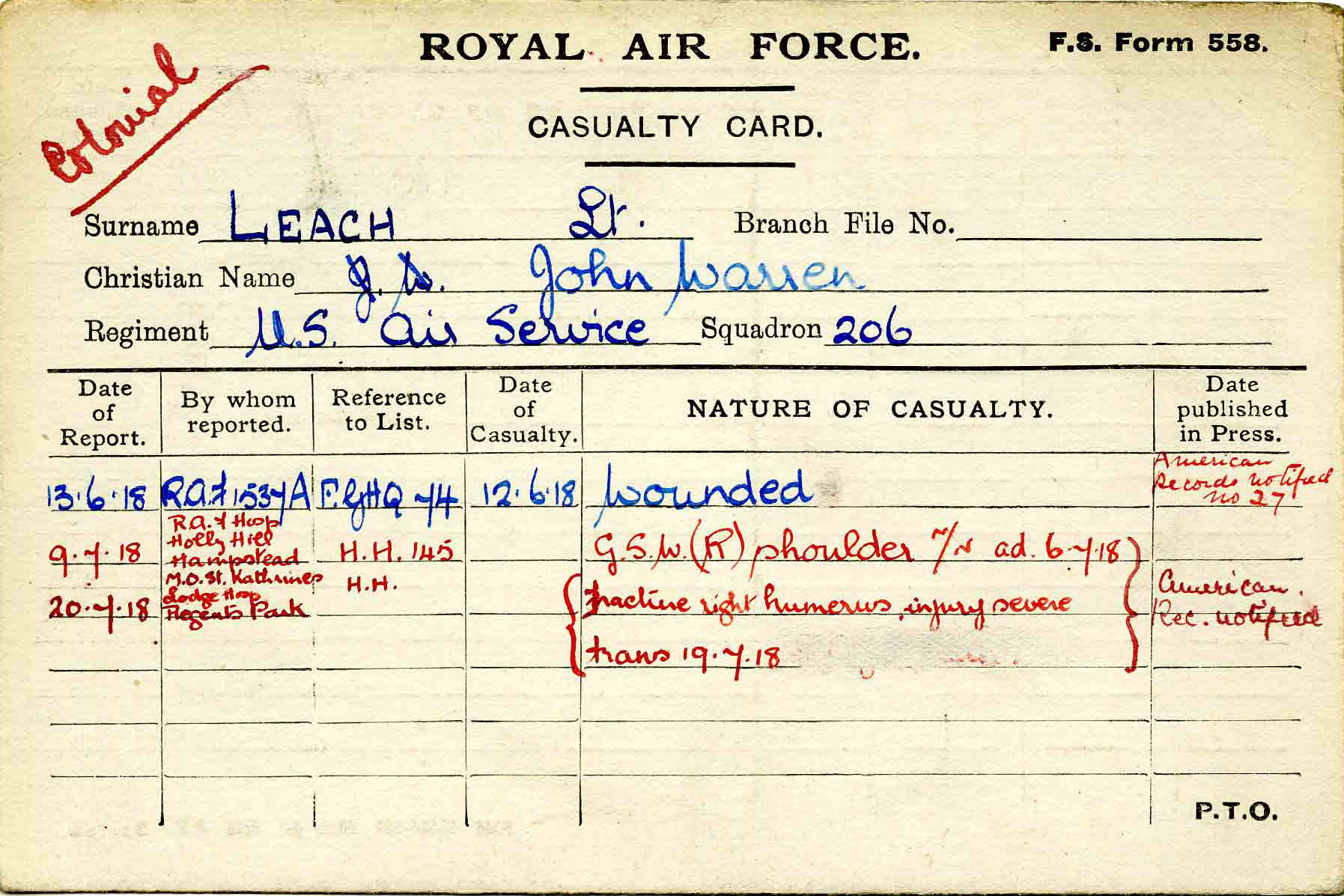

A flight of planes from No. 206 Squadron set out the next day (June 12, 1918) in order, apparently, once again to drop bombs on Courtrai.31 The initial formation was probably nine planes, but three, including Leach’s, apparently got separated from the other six.32 The three were attacked by enemy aircraft, and in the ensuing fight a bullet hit Leach’s right shoulder, wounding him severely. Rather spectacularly, his observer, Chapman, was able to bring the DH.9 and his badly wounded pilot safely back to Alquines.

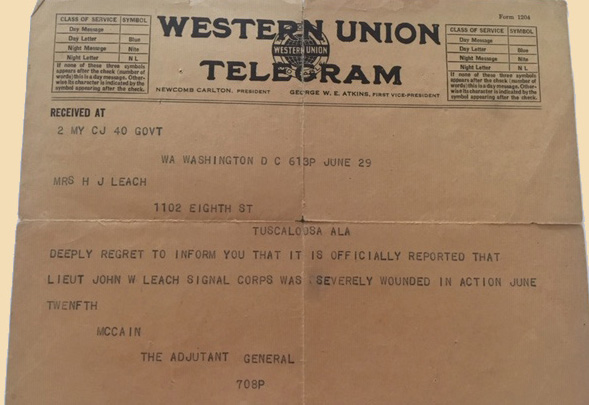

Schlotzhauer sent a cable to Leach’s mother two days after the incident and that same day began a letter to her about it, finishing it up on June 15, 1918.33 The cable appears not to have arrived, for Leach’s parents apparently first heard of his injury on June 29, 1918, when they received cablegrams from the War Department and from a Lieut. Millhouse, described as Leach’s “flying partner”—I have not been able to identify this person.34 Schlotzhauer’s letter reached Leach’s mother on July 12, 1918. It includes the first of several accounts of what happened to Leach and is perhaps the most reliable (the official record is sparse: not even the serial number of the plane Leach and Chapman were flying is recorded).35

As to how the accident occurred: There were three machines on duty over the lines, of which Warren was one. They were attacked by 12 enemy aircraft. . . . I must say that a direct hit like that is very uncommon. . . . When Warren was hit, his observer took control of the machine, flew it back to our side of the lines, brought it down 14,000 feet, and landed without crashing. Even though this was more or less with Warren’s help, it was a very nervy feat, and has created quite a bit of favorable comment among the squadron. Warren was immediately taken to Queen Alexander’s [sic; sc. Alexandra’s] hospital after the wound had been dressed . . . The bullet hit in the back of the right shoulder, shattered and perforated the bones in the vicinity and left his body entirely. The doctors commented on the fact that it was lucky the X-ray showed no signs of the bullet or fragments.36

According to aircraft historian John McIntosh Bruce, “the observer’s cockpit [in the D.H.9] contained a dual set of flight controls, but engine controls were not duplicated.”37 Thus Chapman would have been able to set a course and altitude; he would, however, presumably have needed assistance from the wounded Leach in throttling back and eventually cutting the engine for landing—unless Chapman was able to reach the pilot’s engine controls (the pilot and observer cockpits in the DH.9 were close together, so this seems a possibility). Chapman was awarded a Distinguished Flying Medal for his actions; the citation suggests, possibly incorrectly, that Leach was unconscious during all of the return flight.38

Schlotzhauer, in his letter to Leach’s mother, remarks that “It may be some consolation to know that the Hun was officially shot down in flames by the flight commander,” and, indeed, Leach’s flight commander, Stevens, and his observer, Leonard Arthur Christian, are recorded as having shot down a Pfalz DIII that day at 12:32 near Zonnebeke, about twelve miles west-northwest of Courtrai.39

In hospital and afterwards

There is no indication of how long Leach remained at Queen Alexandra’s Hospital at Dunkirk, but, according to a cable from him that his parents received in early July 1918, he was “moving to Paris.”40 His casualty form suggests he was for a time at No. 14 General Hospital (at Wimereux near Boulogne) and indicates that he was transported to England on the ambulance ship Pieter de Conick on July 6, 1918.41 He was initially admitted to the R.A.F. Central Hospital at Holly Hill, Hampstead.42 From there he was transferred to the American Red Cross Hospital No. 23 at St. Katharine’s Lodge, Regent’s Park, with a notation on his casualty card: “fracture right humerus, injury severe.”43 Milnor visited him on July 8, 1918, noting that day in his diary “Went out to the hospital in Regent’s Park to see Leach who is back from France wounded. Got an explosive in the shoulder which came out the back of his neck. Poor chap he is suffering pretty much and they are afraid of [sic] his arm.”

On August 3, 1918, Leach wrote (or perhaps dictated) a letter to his mother and reported that “I sat up in a chair a little while this morning for the first time since I was wounded, so you see I am improving, but it will be some time yet before I am able to be out. . . . The bullet was an explosive one, and when it went in my right arm and shoulder joint, it smashed everything up pretty badly. My arm became infected and has to be drained yet.” He goes on to remark that “For the loss of an arm and all I have suffered is worth, I should say, at least three Huns, and I have only one to my credit, and my observer one, making two for my machine. At any rate I dropped enough bombs on them to blow up a place as big as Tuscaloosa, so maybe after all I have gotten the best of it. . . . If I am up and out in three months, as the doctor says, I may be home for Christmas.”44

News of Leach’s slow and uncertain recovery filtered back to his second Oxford detachment friends. The War Birds entry for August 27, 1918, reports “Leach has been shot through the shoulder and isn’t expected to pull through. Explosive bullet.”

Milnor visited Leach in hospital again on July 21 and September 2, 1918. He records in his diary on September 11, 1918 that “Leach and [Walter] Chalaire came in the office after lunch. Both are doing very well.” About two weeks later, Milnor and Leach lunched together, and Milnor afterwards wrote “Poor chap, his arm doesn’t seem to get much better and he is still in a plaster cast.”44a

On November 6, 1918, Milnor learned that Leach was scheduled to return to the U.S. on the 14th and was arranging for him to take Christmas presents with him. It must have been distressing when Leach learned that “they were not going to let him go home until his wound heald [sic].”44b The armistice presumably changed that, and from the American Red Cross Military Hospital No. 4 at Mossley Hill in Liverpool Leach was assigned to a detachment of “Casual sick” from that hospital on the Mauretania, among the first of the troops to be sent home.45 The ship departed Liverpool on November 25, 1918, and arrived in New York to much fanfare on December 2, 1918—in plenty of time for Christmas. A number of Leach’s fellow second Oxford detachment members were also on the Mauretania, including Chalaire, Dudley Hersey Mudge, Francis Kinloch Read, and Bonham Hagood Bostick, all of whom had also been wounded but were now sufficiently recovered to travel among the well passengers with Milnor and others. The story of Leach’s final flight and wound was one of those picked up by newspaper reporters who met the ship; an account, with some apparent embroidery, appeared in newspapers soon after the Mauretania docked.46

According to an alumni magazine account, soon after arriving home Leach was treated in a hospital in Atlanta where: “It was discovered that a piece of gauze was left in his shoulder after an operation in France. The gauze has been removed and his condition is greatly improved as the result.”46a Nevertheless, as Schlotzhauer related to Blanford, “he never fully recovered from his wound.”47 A listing of disabled officers from 1928 describes the extent of his disability as 67 ½ %. 48 Schlotzhauer’s further remark, that Leach “died in the mid-1930s” was, fortunately, incorrect. Leach lived until 1954, having gone on to a career in insurance, banking, and real estate, initially in Florida and Georgia, and then back in his home state of Alabama.49

mrsmcq March 13, 2019; minor revisions prompted by Schlotzhauer’s log book August 21, 2023

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Leach’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for John Warren Leach. Other early records (Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Warren Leach and Groves’s The Alstons and Allstons of North and South Carolina) confirm the year. Later documents (Ancestry.com, Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936–2007, record for John Warren Leach and Ancestry.com, U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925–1963, record for John Warren Leach) give his birth year as 1895. His place and date of death are taken from “Birmingham Real Estate Man Dies.” The image is from a painting of Leach; I am grateful to his granddaughter, Warren B. Cain, for forwarding a photo of it to me and permitting me to reproduce it here.

2 Owen, History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography, vol. IV, p. 1022. On Leach’s descent, see documents at Ancestry.com.

3 On James W. and John F. Warren, see “The Nestor of Journalism.”

4 See, for example, “The Football Outlook at High School,” and “Society: Personals.” See Catalogue of the University of Alabama for the College Year 1914–15 and Announcements for 1915–16, p. 168, for his university attendance.

5 R. L. Polk & Co., R. L. Polk and Co.’s Tuscaloosa City Directory 1916-1917.

6 “Warren Leach at Aviation School.”

7 “Warren Leach in England.”

7a “Chester Pudrith, with American Detachment Royal Flying Corps, Writes from England.” In the newspaper’s publication of the letter, Leach’s name has been mistranscribed as “Warren Teoch.”

8 See Leach, R.F.C. Training Transfer Card.

9 See Fremont Cutler Foss’s list of “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers.

10 On the commander of 37 Squadron, see Leach’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card. On the squadron’s locations and planes, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, pp. 402–03. That B.E.2s were nevertheless still used by the pilots of No. 37 is apparent from the Goldhanger Flight Station 1917 – 1918 Operational Records that can be accessed via a link at “37-Squadron Night Landing Grounds.”

11 Here and subsequently information about Leach’s activities relies, unless otherwise noted, on his Pilot’s Flying Log Book. “Capt. Sowry” was almost certainly Frederick Sowrey, who took Schlotzhauer up the same day; see Schlotzhauer’s Pilot’s Flying Log Book.

12 I have found no official documentation of the requirements for a commission, but there was an understanding that a pilot had to have flown twenty hours solo; see, for example, Hooper, Somewhere in France, letters of December 28, 1917, and January 31 and February 14, 1918.

13 I have supplied the letter prefixes for Leach’s planes; he omits them in his log book.

14 See cablegrams 597-S (February 12, 1918) and 813-R (February 20, 1918). McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205” puts Leach on active duty on March 11, 1918; see also “First Lieutenant Warren Leach.” Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35” indicates that Leach reported for active duty on March 9, 1918. A memo (now among the possessions of Leach’s granddaughter, Warren B. Cain) to Leach dated March 2, 1918, from Captain J. A. Ripley of the Signal Reserve Corps, Aviation Section, indicates that Leach’s date of rank was February 20, 1918, and that he had been placed on active duty.

15 See Leach’s log book and his R.F.C. Training Transfer Card.

16 Deetjen, diary entry for April 8, 1918.

17 Document attached to Leach, R.F.C. Training Transfer Card.

18 See also “Lieut. J W Leach USAS,” reproduced above.

19 See the casualty forms for Leach, Schlotzhauer, and Stier: “Lieut. J W Leach USAS,” “Lieut. H A Schlotzhauer U. S. A. S.,” and “Lieut. H D Stier USAS.” The entries for the three men in Munsell, “Air Service History,” pp. 235 (42), 241 (48), and 242 (49) all read “25 May, 1918 – Posted to R.A.F. and 206 R.A.F.,” and Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 2, p. 21, list all three as having been posted to 206 on May 25, 1918. Munsell and Blanford presumably worked from the same document or similar documents which did not differentiate between postings to the R.A.F. and assignment to an R.A.F. squadron.

20 “Lieut. Warren Leach, Tuscaloasa [sic] Birdman, Tells in Letter of Air Fighting.”

21 Quotations are taken from Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 147. Blanford’s two-part article is one of the few extensive sources of information on No. 206 Squadron in World War I. For a succinct summary of 206’s activities in the early part of 1918 (prior to Blanford’s arrival), see Bruce, “The De Havilland D.H.9,” pt. 1, p. 388. The chapters on 206 during this period in Gunn’s Naught Escapes Us, rely heavily on Blanford as well as a few other source documents in the 206 Squadron Archives. Document AIR 27/1221 in The National Archives (UK) includes merely a three and a half page summary of operations during the period.

22 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 117, provides a version of this regulation, as do Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 35.

23 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 147. In Blanford’s account, Heron had arrived the same day as himself, but this is not borne out by Heron’s casualty form (“2nd Lieut. F T Heron RAF”).

24 “Lieut. Warren Leach, Tuscaloasa [sic] Birdman, Tells in Letter of Air Fighting.”

25 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 1, p. 148.

26 “Lieut. Warren Leach, Tuscaloasa [sic] Birdman, Tells in Letter of Air Fighting.”

27 Ibid.

28 “Lieut. Warren Leach, Tuscaloasa [sic] Birdman, Tells in Letter of Air Fighting.” Leach’s account as it is reproduced in the newspaper appears to conflate incidents. There are also some apparent discrepancies (without the original letter, one cannot know whether to attribute them to Leach or an editor). He writes of having “been on nine ‘big shows,” by June 8, 1918, whereas his log book records five bombing raids through that date. Similarly, he writes that “We fly from 15,000 to 20,000 feet now . . . We have to take oxygen with us for we are up from two to four hours at a time.” According to his log book, Leach’s highest flights were at 14,000 ft, so he is apparently here writing of the squadron generally. Blanford mentions in passing “recourse to our primitive oxygen apparatus” during a long reconnaissance flight when he and his pilot were at 21,000 feet (“Sans Escort,” pt 1, p. 148).

29 See entries for members of No. 206 Squadron in “100 Years Ago Today – 7 June 1918.”

30 “Lieut. Warren Leach, Tuscaloasa [sic] Birdman, Tells in Letter of Air Fighting”; “Lieut. Leach Writes Mother of his Wounds.”

31 A newspaper account from December 1918 that is at least second-hand and in some respects not reliable (in “Camp Mills Ringing To-day”) indicates that Courtrai was the object of the raid, and Blanford (“Sans Escort,” Pt. 2, p. 24) records a raid on Courtrai on June 12, 1918.

32 “Camp Mills Ringing To-day.”

33 “Warren Leach Received Bullet Wound in Right Shoulder, Says Letter.”

34 “Lieut. Warren Leach Severely Wounded in Action While Flying.”

35 The number does not appear on the R.A.F. casualty card for the incident (“Leach, J.W.”), and neither Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, nor Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File, provides a number. I am grateful to a Great War Forum member whose examination of the relevant R.A.F. weekly aircraft return reports confirms that Leach’s plane did not sustain damage that warranted inclusion in a report.

36 Schlotzhauer’s letter is reproduced in “Warren Leach Received Bullet Wound in Right Shoulder, Says Letter.”

37 Bruce, “The De Havilland D.H.9,” pt. 1, p. 388.

38 Chapman’s D.F.M. citation appears on p. 11257 of “Awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal.”

39 See the entry for DH.9 C6240 in Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File.

40 “Lieut. Leach Goes to Paris to Recuperate.”

41 “Lieut. J W Leach USAS.”

42 “Leach, J.W. (John Warren).”

43 Ibid.

44 “Lieut. Leach Writes Mother of his Wounds.”

44a Milnor, diary entry for September 23, 1918.

44b Milnor, diary entry for November 8, 1918.

45 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for casual sick from Amer. Red Cross Mil. Hosp. No. 4, on Mauretania.

46 “Camp Mills Ringing To-day with Tales of Valor in Air, Brought by New York Boys”; “Thrilling Flights in Air Told of by Returned Fliers.”

46a “Alumni Notes” (The Delta), p. 682.

47 Blanford, “Sans Escort,” pt. 2, p. 21.

48 Congressional Record, Senate, March 15, 1928, p. 4757.

49 Ancestry.com, Alabama, Surname Files Expanded, 1702–1981, record for J Warren Leach.