(Brookline, Massachusetts, April 15, 1892 – County of Middlesex War Hospital, Napsbury, St. Albans, England, February 23, 1918).1

Oxford ✯ Grantham ✯ Northolt ✯ London Colney

On his father’s side, Joseph Frederick Stillman, Jr., was descended from a George Stillman of Steeple Ashton in Wiltshire, England, who emigrated to America probably in the late 1670s. A son, also George, emigrated separately later, having remained in England to study medicine.2 He joined his father and a large number of step-siblings in Connecticut in about 1700, but soon after settled in Westerley, Rhode Island. There followed Joseph I, Joseph II, and a Joseph III, all in Westerley. The third Joseph Stillman had a son Alfred, who was the grandfather of Joseph Frederick Stillman, Jr. Alfred Stillman became an engineer and lived and worked in New York City, where Joseph Frederick Stillman, Sr., was born. In 1879 the latter married Elizabeth McCannon Schley, a descendant of the talented musician and school teacher Johannes Thomas Schley of Mörzheim in the Platinate; Schley had emigrated to Washington County, Maryland, in about 1744.3 Joseph Frederick Stillman, Sr., was a successful sugar refiner. For some time he and his wife lived in Brookline, Massachusetts, where all of their seven children are recorded as having been born.4 Joseph Frederick Stillman, Jr., (“Fred,” to distinguish him from his father, “Joseph”) was the youngest, with three sisters and three brothers.

In 1897 the family relocated to Brooklyn, New York, where the young Stillman attended the “private, small and selective” Brooklyn Latin School for Boys.5 The family moved again in 1904, this time to the Murray Hill neighborhood of Manhattan; the Stillmans were well-to-do and socially prominent. In 1906 Stillman began attending St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire. He graduated in 1911 and that fall entered Yale. Both in prep school and college he excelled at sports, particularly football and crew.6 In late August 1914, a passenger list shows him arriving in New York from England; he was thus among the relatively few men of the second Oxford detachment who had been in England or Europe prior to 1917.7

After graduating from Yale in 1915 Stillman went to work as a bonds salesman in New York for the banking firm of Blodget and Company.8 In April of 1916, Stillman joined the First Armored Motor Battery of the New York National Guard.9 The unit was not deployed to Mexico with other units of the N.Y. National Guard, and in the summer of 1917 it was decided that it would not become part of the regular army.10 Perhaps already aware of this latter development, Stillman transferred to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps in late June 1917. His training on motor car engines would presumably have served him well when studying airplane engines at the Ohio State University’s School of Military Aeronautics, to which he was assigned. After two months of ground school at O.S.U., Stillman and twenty-five others graduated on August 25, 1917.11 For most of the two months it was assumed that they would be sent to France for their actual flight training—government flight training facilities in the U.S. existed at this time mostly on paper. However, sometime in August, it was announced that there were openings for flight training in Foggia, Italy. Stillman was one of eighteen men from this ground school class at O.S.U. who chose or were chosen to train there, and he thus became one of the 150 men of the “Italian detachment.”

After their graduation the men had some free time during which many of them visited home. Then Stillman and those expecting to train in Italy gathered at Mineola on Long Island. On September 18, 1917, they were ferried to the west side of Manhattan to board the Carmania at a Cunard pier in the Hudson River. They sailed initially to Halifax; from there, on September 21, 1917, the Carmania set out as part of a convoy to cross the Atlantic. The men of the detachment travelled first class. Stillman shared a stateroom with Joseph Kirkbride Milnor and Dudley Hersey Mudge, who had been at O.S.U., and with William Hamlin Neely, who had been at ground school at Princeton. The men had plenty of leisure, apart from Italian lessons given by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them. They also, once the ship entered particularly dangerous waters close to the British Isles, were assigned to submarine watch duty, which was, fortunately, uneventful.

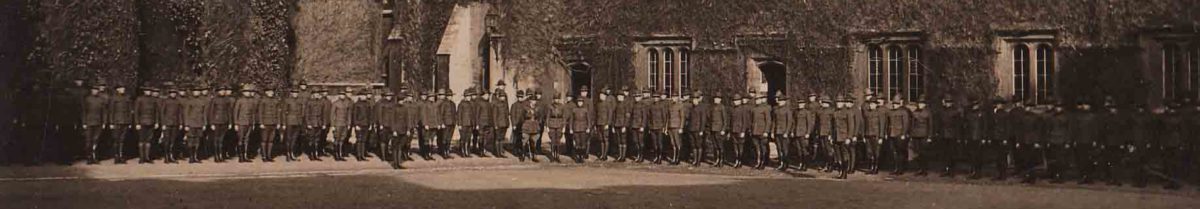

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, there was a change of plan. The men would not go on to Italy but remain in England and, even worse, as it seemed, go through ground school all over again. According to Milnor “We were a very sore and disappointed bunch of fellows when we entrained at 11:45.”12 The train took them to Oxford and Oxford University, where the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics was located. The “Italian detachment” became the “second Oxford detachment”—another detachment of fifty American pilots in training having arrived there a month earlier.

The first night was spent scattered among four Oxford colleges, but the next day the four groups were consolidated into two. Ninety men under Elliott White Springs were assigned to Christ Church, and sixty, including Stillman and Milnor, in the charge of Springs’s deputy, William Ludwig Deetjen, went to Queen’s. Milnor wrote that “Fred [Stillman] and I got a small [room] on the top floor of staircase #2 (room # 7) facing the Square formed by the buildings and the tower clock. We ought to be comfortable as there is a small fire place. We will need this as it is awfully cold and raw, and we are in the middle of the rainy season.”

Having arrived on a Tuesday, one day too late for the start of that week’s classes, the men were free to settle in and explore Oxford and the surrounding area. On Friday Stillman and Milnor had a late pass and went to the theater. The next day, Stillman and his O.S.U. classmate Parr Hooper “took a row down the Thames in a double sculled gig. It had sliding seats, outriggers, and was almost like a racing boat. We had a bit of trouble steering about the turns but we surely did fly along and saw beautiful country, also had tea at a quaint old inn.”13 On Sunday Stillman, Hooper, and Milnor “took a bike ride up to Woodstock and visited the Castle of the Duke of Marlborough, Blenheim Park.”14

Classes, which began on Monday, October 8, 1917, were not especially taxing: “about the same as we had at Columbus, except they have actual engines that are used etc., and it made it a little more interesting.”15 Also making classes more interesting was that the British instructors had war flying experience, unlike their American counterparts.

The class schedule left ample time for sports. On Tuesday of the first week of classes Deetjen noted he had “Had quite a workout on the river today. Formed a 4 oared crew from our detachment and rowed on the Thames. . . . Stillman (stroke) [Donald Swett] Poler (3), Deetjen (2) [Phillips Merrill] Payson (bow) [Donald Elsworth] Carlton (cox).”16

After about two weeks all the men were moved from Christ Church and Queen’s to Exeter College; it was thought that it would be easier to supervise the high-spirited Americans if they were all in one college. “Fred, Jake [Julian Carr] Stanley, Dud [Mudge] and I [Milnor] had a large room on the ground floor.”17

On the last Saturday of the month, Deetjen wrote in his diary that “We went out on the river today, and I stroked our crew of Payson, [Harry Adam] Schlotzhauer, Stillman & [Alexander Miguel] Roberts coxswain. We never knew when we left Exeter that we were in for a final race. Well we just naturally pulled the bottom out of the river and won by two boat lengths from Corpus Christi. We were given passes tonight as a reward.” That same day Hooper wrote that “Tomorrow afternoon, Stillman, and [Lynn Lemuel] Stratton and I are going to take out shells and row as far down the Thames as we dare, get dinner at some inn down there and then row back by the light of the full moon.” This particular plan was scuppered when Parr was pulled to take part in a cross-country race instead. Rainy weather and routine classes were enlivened for Stillman and Milnor by meals at the Mitre and the Randolph and billiards and card games with O.S.U. classmates Philip Dietz, Charles Carvel Fleet, Clarence Bernard Maloney, and Guy Samuel King Wheeler.18 On the last evening of October Deetjen noted that “Fred Stillman & I had dinner at Buol’s and then went to the movies.”

The men were eager to start flight training, and in early November twenty of them were able to go to Stamford for instruction. Because of a shortage of training places and equipment, however, the rest of the men, including Stillman, were ordered to a machine gun school, Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire. Both Springs and Deetjen were among the men posted to Stamford, so “Fred was put in charge in Springs’ place”; according to Clarence Horne Fry, Stillman was “elected.”19 Once arrived at Grantham on November 3, 1917, the men were assigned to huts. Stillman, Milnor, and eight others, all from O.S.U., shared a hut, with Stillman in charge of them.20 A few days later Fremont Cutler Foss noted in his diary that “Stillman got a letter today from some of the fellows who followed us from the U.S. who are in Italy. They fly every day the weather is fine. Makes us feel more disappointed than ever.”21

The course at Harrowby Camp was to be two weeks of instruction and practice on the Vickers machine gun, and then two on the Lewis. In mid-November, as they were finishing up on the Vickers, it was determined that there were places for fifty of the cadets at various training squadrons. Hooper wrote to his parents that “Fifty of us are going to be posted to flying schools next Monday. The selection was made by London and must have been a big lottery. I hope I was one of the fortunate ones. They say the adjutant here has the list, but has not let any one see it yet.” The next day, November 14, 1917, Hooper wrote happily: “Now I have some good news. This morning when we fell in to go on the range, Capt. [Stephen Leslie] Hibbard, our C.O. (Commanding Officer, British) read out the 50 names of the men who go to flying schools next Monday. I had the best of luck. I am going, and with what I think are the very best fellows. Those who are with me and were in my squad at Columbus are Stillman (who is the cadet C.O. of this whole detachment now). . . .”

Some of those not selected were, unsurprisingly, disappointed. Foss went so far as to say that “Stillman picked out his friends to the last man. Everyone is sore. . . . ”22 This does not accord with Hooper’s saying the decision was made in London, and Milnor, who was rooming with Stillman, makes no mention in his diary of Stillman being involved in the selection process. It is nevertheless notable that, of the fifty men, eighteen had been at O.S.U. for ground school, while the other six Schools of Military Aeronautics were less well represented.

Be that as it may: Stillman and Hooper, along with Dudley Hersey Mudge, John Chadbourn Rorison, Roland Hammond Ritter, Edward Frank Hollander, Conrad Henry Matthiessen, Field Eugene Kindley, Reuben Lee Paskill, and Walter Burnside Knox, were posted to Northolt, on the northwest outskirts of London.23 “We packed up Sunday evening [November 18, 1917] and loaded our luggage on motor lurries [sic] at sunrise Monday. The train for London left at 7:30. We had a 1st class compartment and read the papers and watched the scenery. We arrived at King’s Cross Station unexpectedly soon 10:45. Fred and Dud Mudge went up to Paddington Station with our luggage on horse drawn busses.” The men explored London and then “we took the train for Northolt at 1:57 from Paddington. . . . We got to Northolt about 4 and after visiting headquarters had tea in our mess and then got our billets and baggage arranged. Everybody here are officers except the mechanics. There are about 150 men training, 2 elementary squadrons and one advanced. We 10 Americans (5 in the 2nd squadron and 5 in the 4th squadron) are ranked as cadets but are treated as officers.”24

Weather was initially “dud,” i.e., unsatisfactory for flying, and, since the men had one day off every two weeks, Hooper, Mudge, Ritter, and Stillman went into London the afternoon of November 21, 1917, for some shopping, followed by dinner at the Grill Room in the Piccadilly Hotel and a show, the long-running and very popular “Chu-Chin-Chow.”25

Hooper made his first flight the next day; Stillman presumably also started flying around the same time. The planes used by the elementary squadrons were Maurice Farman S. 11 Shorthorns, often referred to as Rumpties. These “pusher” biplanes (i.e., ones with the propeller mounted behind the cockpit) had been developed before the war and were used on the Western Front into 1915; after that they were ubiquitous in elementary training squadrons. They were outfitted with controls for both pilot and passenger, and the students initially would go up with an instructor who piloted the plane but could let the student feel what was happening on his own set of controls; after some practice, the two could reverse roles. The next step was for the student to go up solo; Hooper and Ritter did this in early December, and Stillman’s experience was presumably similar.26

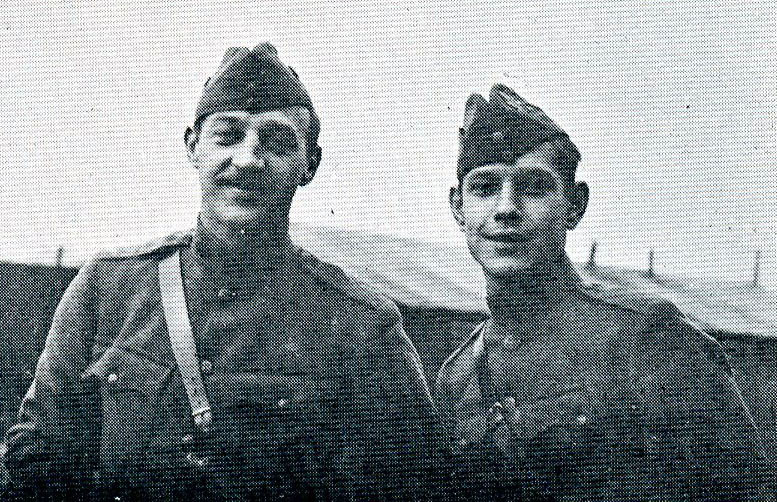

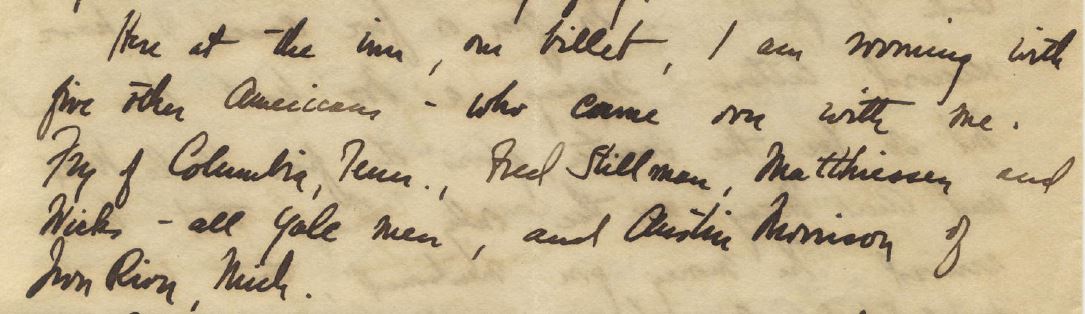

The men completed their elementary training at Northolt around December 18, 1917. Several of them, including Hooper and Stillman were next posted to London Colney, just south of St. Albans. There were two training squadrons there, and Hooper went to No. 56 Training Squadron, while Stillman was at No. 74 T.S., across the field from 56. Stillman was billeted at the Red Lion in nearby Radlett, along with Marvin Kent Curtis, Clarence Horne Fry, Matthiessen, Glenn Dickenson Wicks, and Austin Finley Morrison. “A tender (motor bus) calls for us here at the Red Lion at 8:15 and takes us to the aerodrome for breakfast.”27

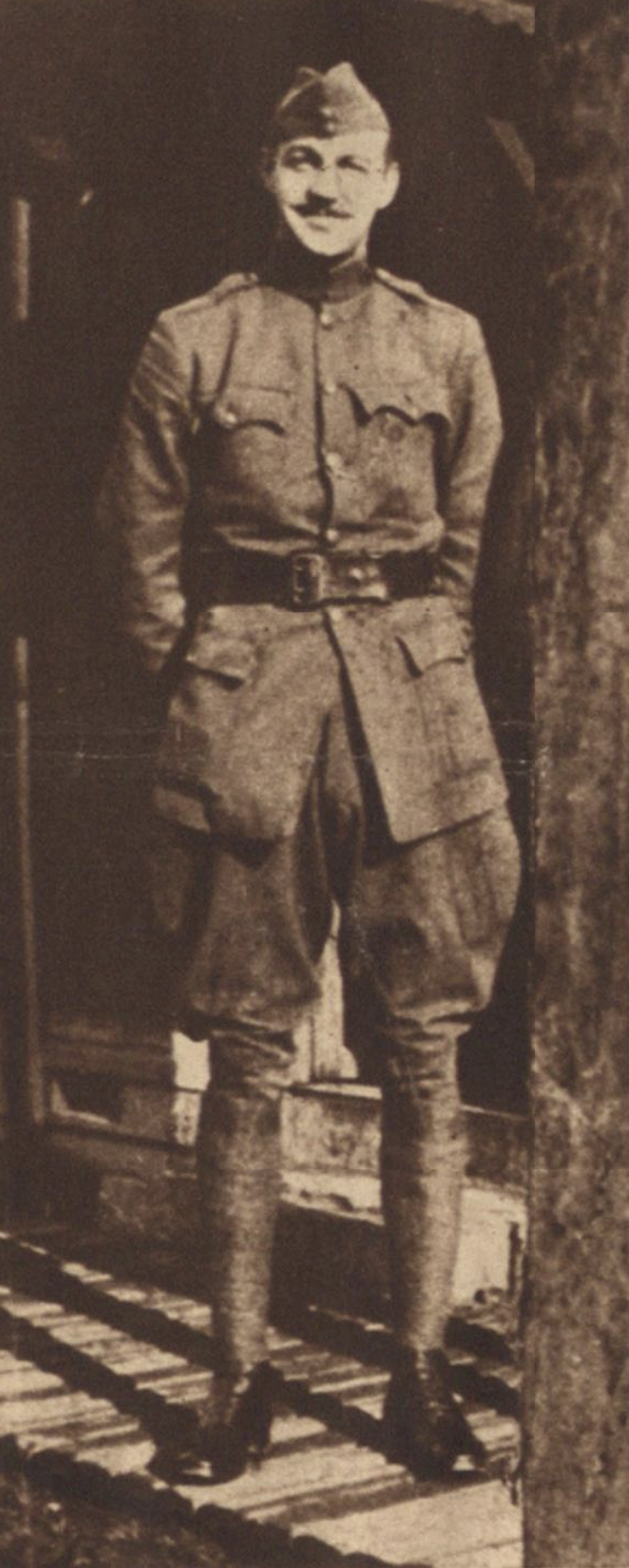

The men made a good impression on their more experienced British squadron mates. James Ira Thomas Jones of No. 74 Squadron recalled having heard derogatory stories about Americans, “but the twenty or thirty men who came to London Colney were fine fellows, the flower of their great nation. . . . Our school [74 T.S.] was lucky enough to get such grand types as Ken [sic] Curtis . . . Fred Stillman . . . .” Of the latter Jones writes: “Fred Stillman, a giant in stature and in heart, was a favourite in the mess.”28

At London Colney Stillman would have trained on Avros, again initially dual and then solo. Hooper, at 56 T.S., made his first solo flight in an Avro on January 23, 1918; Curtis, at 74, did not go solo until February 13, 1918.29

Stillman, like Hooper, evidently progressed fairly rapidly. By February 8, 1918, he was not only flying solo, but also practicing fighting tactics with another machine in the air. He, in Avro C4377 that day, and Lt. Douglas Quirk Ellis, in Avro B4344, “were instructed to practise attacking, the cadet’s [Stillman’s] machine to fly straight and the lieutenant to manœuvre and attack from different angles, but not to approach within 50 feet.”30 Other newspaper accounts describe the two pilots as flying “in the direction of the sun.”31 If this last is accurate, it may have made it difficult to see.

Eugene Hoy Barksdale, another cadet at No. 74 Training Squadron, wrote in his diary the next day that: “At 12:30 P.M. Fred Stillman of N.Y. collided with Lt. D. Q. Ellis of Toronto, Canada at about 1500 feet high.” Jones recalled

standing outside the mess when it happened. Although the collision occurred about a mile away, I distinctly heard the crash as the planes met. Looking up, I saw the two machines gliding earthward, interlocked, from a height of 2,000 feet. A wisp of black smoke was trailing from the falling wreckage. A few seconds later, the aeroplanes were enveloped in flames. It was a ghastly sight. The floating furnace drifted towards the aerodrome, eventually coming to rest on the outskirts, not far from Radlett golf-course. I jumped into a car and stepped hard on the accelerator. When I got to the spot, Stillman was walking about, badly burned, but fully conscious. Poor old Ellis was still in the blazing aircraft. No doubt he had died before the planes touched the ground.

Stillman tried to make a joke of his injuries, but he was plainly much more badly injured than he thought. We got him to hospital as quickly as we could. I visited him daily. He could not move. His body, arms and head were swathed in mummy-like bandages. Just three little holes had been left for his eyes and mouth. Yet to listen to his cheery talk, you would have thought he was in the best of health.32

Stillman was taken to the nearby Napsbury Hospital (County of Middlesex War Hospital). Another frequent visitor at Stillman’s bedside was Hooper, who “got in touch with Frank Williams and he to my great delight came out armed with official orders from our aviation headquarters and applied the best and most modern treatment. Fred will be O.K. in a little while.”33 (Francis Thomas Williams had received his M.D. from Johns Hopkins and worked as a doctor in England and France; the “modern treatment” may have been ambrine, a paraffin preparation that was painted or sprayed on burns.) Three of Stillman’s siblings, Alfred, Ruth, and Lisa, were in France doing medical work in support of the war effort. On February 14, 1918, Hooper wrote that “Fred Stillman is getting along pretty well. His brother and two sisters have come here from France to be with him. He will have a right tough time for some weeks.”

For whatever reason, possibly an embolism, on February 23, 1918, Stillman took a sudden turn for the worse and died.34 A funeral was held for him at the hospital the morning of February 26, 1918; among the pall bearers were Curtis and John McGavock Grider.35 Jesse Frank Campbell noted that “All the Americans were there together with Capt Stillman and his two sisters.”36

Stillman’s body was returned to the U.S. Funeral services took place at his parents’ house on March 24, 1918, and he was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.37

mrsmcq October 7, 2025

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Stillman’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Joseph Frederick Stillman. His place and date of death are taken from “Stillman Joseph F. Jr.” The photo is a detail from a group photo of Stillman’s ground school class.

2 On the Stillmans, see Adams, The History of Ancient Wethersfield, Connecticut, vol. 2, pp. 667–84; Stillman, History and genealogy of George Stillman, 1st; Duermyer, Alfred Stillman; and records available at Ancestry.com.

3 On Johannes Thomas Schley, see Wust, “Johannes Thomas Schley”; on the Schleys, see records available at Ancestry.com.

4 Census records indicate the two oldest children were born in “Boston,” but draft registration and passport application records specify Brookline.

5 Spellen, “Home to a Wealthy Family.”

6 St. Paul’s School in the Great War, p. 42; Yale University, Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University Deceased During the Year Ending July 1, 1918, p. 721.

7 Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, record for Joseph F Stellman [sic].

8 Yale University, Obituary Record, p. 721; see also draft registration cited above.

9 Nettleton, Yale in the World War, vol. 1, p. 184.

10 “Recruiting Slump Due to False Rumour.”

11 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

12 Milnor, diary entry for October 2, 1917.

13 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of October 7, 1917.

14 Ibid. See also Milnor’s diary entry for this date.

15 Milnor, diary entry for October 8, 1917.

16 Deetjen, diary entry for October 9, 1917.

17 Milnor, diary entry for October 22, 1917.

18 Milnor, diary entries for October 24 and 30, 1917.

19 Milnor, diary entry for November 2, 1917; Fry, letter of November 4, 1917.

20 Milnor, diary entry for November 3, 1917.

21 Foss, diary entry for November 8, 1917.

22 Foss, diary entry for November 13, 1917.

23 See Foss, diary entry for November 15, 1917, which lists the 50 men posted, along with their assignments.

24 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917. “Lurry” is alternative form of “lorry” (truck).

25 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917.

26 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 6, 1917.

27 Curtis, letter of January 19, 1918.

28 Jones, Tiger Squadron, pp. 60, 61.

29 See their respective Pilot’s Flying Log Books.

30 “Collision in the Air.” The plane serial numbers are taken from the relevant casualty cards: “Stillman, J.H. (Joseph H.) [sic],” “Stillman, J.S.,”and “Ellis, D.Q. (Douglas Quirk).”

31 “Collided in the Air.”

32 Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 61; Jones erroneously recalled February 7, 1918, as the date of Stillman’s accident.

33 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of February 10, 1918.

34 Yale University, Obituary Record, p. 722.

35 Curtis, letter of February 27, 1918 ; Grider and Jacobs, Marse John Goes to War, pp. 79–80.

36 Jesse Campbell, diary entry for February 26, 1918.

37 “Died”; Yale University, Obituary Record, p. 722.