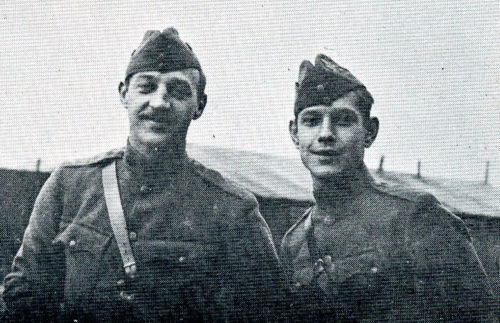

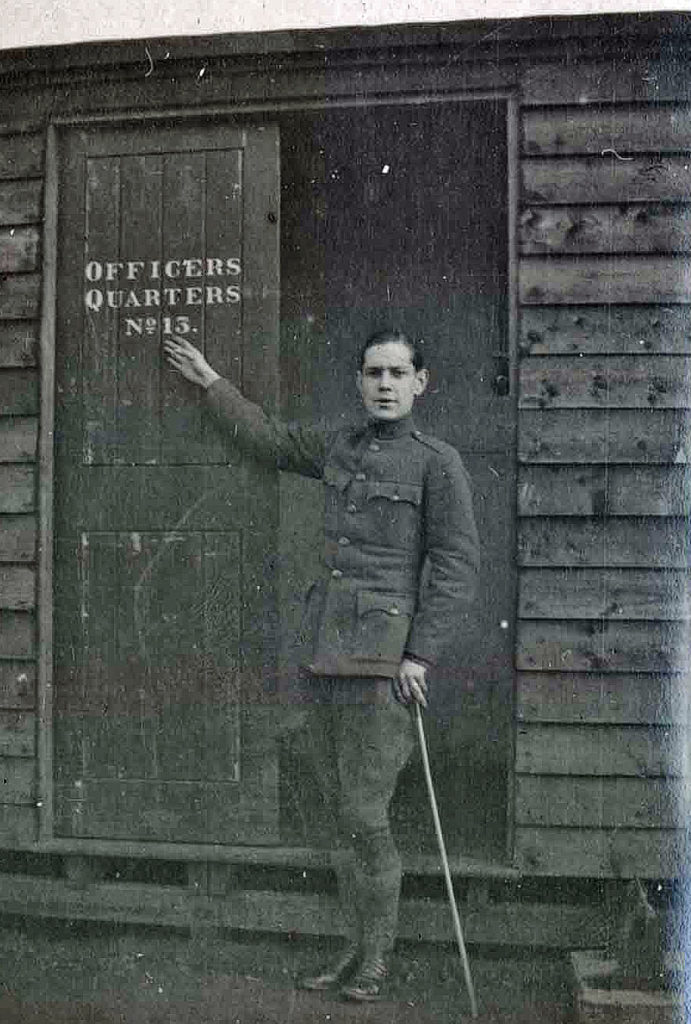

(Chicago, Illinois, March 11, 1893 – Ridgewood, New Jersey, October 2, 1965).1

Oxford ✯ Grantham ✯ Tadcaster ✯ South Carlton ✯ London ✯ Returning home

Milnor was descended from a Yorkshire Quaker, Joseph Milnor, who emigrated to Pennsylvania in the late seventeenth century; descendants settled in New Jersey and other states on the East Coast. Both of Milnor’s grandfathers were successful merchants, and his father, Lloyd Milnor, was for a time president of Spaulding & Co., a large silver and jewelry firm with headquarters in Chicago, where Milnor was born.2 When Milnor, who seems to have gone by his middle name, often shortened to “Kirk,” was in his teens, the family returned to New Jersey, where his older sister and only sibling had been born.3

Milnor attended private schools: Hoosac School in New York and Kent School in Connecticut; like his father he dispensed with college.4 When he registered for the draft he was working as a bonds salesman for a New York firm, Blodget & Co.; he noted on his draft form that he had served four years in the New Jersey National Guard.5 In June 1917 he enlisted in the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps, and he began ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University towards the end of that month.6 In July 1917 his engagement to Beatrice Coolidge McCarthy was announced; they would wait until after the war to marry.7

Milnor’s ground school class graduated August 25, 1917.8 He was one of eighteen from this class at O.S.U. who chose or were chosen to train in Italy and was thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment.”

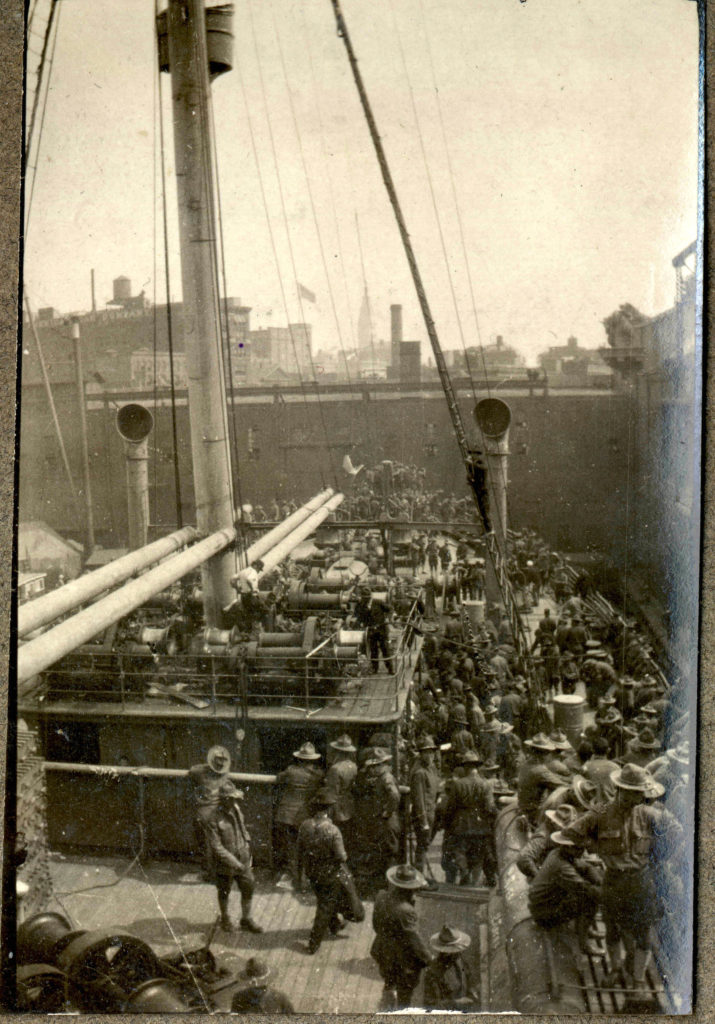

The men assembled at Mineola on Long Island in early September and set out for Europe from New York on the Carmania on September 18, 1917. The detachment travelled first class, which, according to Milnor, did not sit well with some of the officers on board, who “tried to make rules barring us from certain parts of the ship.” The detachment’s commanding officer, Major Leslie MacDill, “a prince, would not stand for it and so we still have all the privileges of any officer.” The men were instructed to replace the U.S. insignia on their collars with the crossed flags of the signal corps “to distinguish us from the regulars.”9 Milnor shared a stateroom with Joseph Frederick Stillman, Dudley Hersey Mudge, and William Hamlin Neely.10 Stillman was one of Milnor’s ground school classmates and had, like Milnor, worked for Blodget & Co.; Mudge was in the class behind them at O.S.U.; Neely had been at Princeton. The Carmania sailed initially to Halifax and then left Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. The men’s only obligations were an hour of Italian daily and boat drills. Italian was usually taught by Fiorella La Guardia, but on at least one occasion by Albert Spalding, the well-known concert violinist. Once the convoy entered dangerous waters around September 27, 1918, the men took turns at submarine watch. They encountered rough seas from time to time, but Milnor, unlike some of the other men, found that this did not affect him adversely: “the rolling made sleep much easier.”11

Oxford

The Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, and “we were then informed that our orders had been changed and that instead of going to Italy, as planned, we were going to Oxford to another Ground School. It seems the English Air Board asked for 150 Americans to train and simply grabbed us.”12 MacDill and La Guardia tried to have the new orders rescinded, but in vain. They went on to France, leaving Captain John Warren Swann—who had been the supply officer on the Carmania—in charge. “We were a very sore and disappointed bunch of fellows when we entrained at 11:45 under the direction of Lieut [Geoffrey James] Dwyer, who came down from the Embassy to look out for us.”13 Arriving early that evening at Oxford University, home to the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics, the men—now called cadets—were assigned for the night to Oxford colleges: Jesus, Christ Church, Queen’s, and Exeter; Milnor spent his first night in Exeter. The next day the four groups were consolidated into two. Ninety men under Elliott White Springs were assigned to Christ Church, and sixty, including Milnor, under Springs’s deputy, William Ludwig Deetjen, to Queen’s—where they encountered the fifty men of the “first Oxford detachment,” who had arrived a month previously. “Fred and I got a small [room] on the top floor of staircase #2 (room # 7) facing the Square formed by the buildings and the tower clock. We ought to be comfortable as there is a small fire place. We will need this as it is awfully cold and raw, and we are in the middle of the rainy season.”

Having arrived too late for the start of that week’s classes, the men were free to settle in and explore Oxford and surroundings. Milnor and Stillman went to the theater one evening when they had a late pass, and on the weekend were joined by Parr Hooper on a rainy, windy bike ride out to Woodstock and a walk through the grounds of Blenheim Palace.14 Like the rest of the approximately 1500 cadets at Oxford, they now wore white bands on their campaign hats; these latter they exchanged mid-month for the very different R.F.C. caps. Classes began on Monday, October 8, 1917, and were not especially taxing: “about the same as we had at Columbus, except they have actual engines that are used etc., and it made it a little more interesting.”15 Two weeks later all the men of the second Oxford detachment were moved to Exeter College in the aftermath of a riotous farewell party for the first Oxford detachment that annoyed the British authorities. “Fred [Stillman], Jake [Julian Carr] Stanley, Dud [Mudge] and I had a large room on the ground floor.”16 Rainy weather and routine classes were enlivened by meals at the Mitre and billiards and card games, mainly with O.S.U. classmates Philip Dietz, Charles Carvel Fleet (“Charlie”), Clarence Bernard Maloney (“Mac”), Stillman, and Guy Samuel King Wheeler (“Red”).

Grantham

The men were eager to start flight training, and in early November twenty of them were able to go to Stamford for instruction. Because of a shortage of training places and equipment, however, all but one of the rest of the men, including Milnor, were ordered to a machine gun school, Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire (James Whitworth Stokes, according to the War Birds entry for November 6, 1917, remained behind with appendicitis17). Stillman was now in charge, as both Springs and Deetjen were among the men posted to Stamford.

At Grantham Milnor once again roomed with Stillman, along with eight other men who had been at O.S.U, in one of the Harrowby Camp huts. They arrived at Grantham on Saturday, November 3, 1918; the next day “Red, Mac, [Stanley Cooper] Kerk and I hired a Ford and drove over to Nottingham, about 24 miles” for the afternoon and evening. On Monday two weeks of instruction on the Vickers gun commenced, at the end of which Milnor received the second highest mark in an exam on stoppages and a “certificate of instruction. So some day I may have that to fall back on if I have to quit flying or get hurt and am unable to fly again.”18

Shortly before the end of the Vickers course “There was a rumor afoot that 50 of us were to be posted on Monday [November 19, 1917] to flying Squadrons. Much excitement about it.”19 The next day “The rumor of posting was confirmed. . . . Five of us are going to Tadcaster somewhere up in Yorkshire.” Before leaving for Tadcaster, however, Milnor travelled to London with “Davey” (otherwise unidentified) mainly for the purpose, apparently, of visiting Rae Wygant Whidden. Whidden, who had received his M.D. from Harvard in 1911, was on the staff of Harvard’s Base Hospital No. 5 near Camiers when it was bombed in the night of September 4–5, 1917, and was among those wounded.20 He was apparently a patient in the American Women’s Hospital in Lancaster Gate when Milnor visited him.21 Milnor had perhaps known Whidden in New York; Whidden was on the staff of Bellevue Hospital there from 1912 to 1917.22 “Found him well and expecting to go home for six months about Dec. 1st.”23

Back at Grantham the next day (Sunday, November 18, 1917) Milnor visited the aerodrome at nearby Spittlegate with Dwyer and Stillman and later took part in a farewell dinner with other men from his ground school class: Fleet, Maloney, Roland Hammond Ritter, Hugh Douglas Stier, and Wheeler. He and Stier, along with Henry Bradley Frost, Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, and Joseph Ralph Sandford left the morning of November 19, 1917, for Tadcaster.

Tadcaster

The five bound for Tadcaster, seventy miles north of Grantham, made the first part of the train journey north with ten men who had been assigned to Doncaster, some of whom (Weston Whitney Goodnow, Leonard Joseph Desson, and Bradley Cleaver Lawton) would later join Milnor at South Carlton. Once arrived at Tadcaster, the five men found themselves posted to No. 14 Training Squadron, commanded by Percy Gilbert Ross-Hume.24 Frost, Hamilton, and Sandford were assigned to A flight, and Milnor and Stier to C flight under George Robert Graham Smeddle. The planes used for instruction were Maurice Farman S.11s, known as “Rumpties” or “Rumpeties”; these were “pusher” planes, i.e., ones with the propeller behind the cockpit. This type of plane had been flown at the front early in the war but was now used in training.

Three days after his arrival at Tadcaster, Milnor made his first flight and, unlike most of his fellow detachment members when they first flew, was underwhelmed: “I went up for my first trip at 10.15 and stayed up for 20 minutes at 1200 feet. I was quite disappointed at the lack of a thrill and had no feeling of alarm. It seemed quite natural to be sailing over the country. We made about 60 when flying and 75 when gliding in. It was very ‘bumpy’.”25 Poor weather kept Milnor from flying again until after Thanksgiving (celebrated in Leeds with a dinner and a show). On December 3, 1917, “Smeddle sent for me. We were up for 50 minutes and made 7 landings. I had complete control of the machine for quite a long time and got along very well.” On December 10, 1917, he was able to write in his diary: “Went up in the afternoon for 50 minutes. Have done 6 hrs 25 minutes and I am going Solo tomorrow.”

Milnor’s first solo flights the next day were trying. The plane’s behavior differed when carrying the weight of only one person, and on his first solo landing: “Crashed my undercarriage ignominiously . . . much to Smeddles and my disgust.” He redeemed himself with three perfect landings, and then “On my fourth trip around a D.H.VI got in front of me so I had to dive. Just as I was about to shut off, I saw him again and had to dive again to get out of his way. I then shut off and had landed and was running along the ground when he landed on top of me, smashing both buses pretty badly. Neither of us was hurt at all but his wing tip just missed my head. It was entirely the other fellows fault for not watching where he was going. It made me horribly sore as I could not finish up my landings. I went in to Leeds with Smeddle to celebrate, my first solo not my crash.” That evening, “… it took me a long time to get to sleep as I was pretty shakey and nervous. Anyway I have done 40 minutes solo.”

Another stretch of poor weather kept Milnor grounded until December 18, 1917. On that day, “On my last round I had rather a close call. I hit a bump and dropped about ten feet, my left wind just grazing the top of a tree. It gave me a pretty bad scare but I got around all right and landed O.K. and taxied in to the tarmac. There were several small twigs piled up on my front strut and a fair sized hole punched through my aileron so I guess I was luckier than I thought.” He had now completed his elementary course, as had Stier and Hamilton, so they were now ready to move on.

South Carlton, Avros, and flu

On December 20, 1917, Milnor, Stier, and Hamilton travelled south to No. 45 T.S. at South Carlton near Lincoln, where they “were then given a room large enough for the three of us, no. 1. Hut 13.” No. 45 T.S. was serving as a “pool squadron,” where men took classes and awaited further assignment. Over the course of the week they were joined by Desson, Charles William Harold Douglass, Goodnow, Lawton, and Murton Campbell (the latter moved on to Scampton).

On December 31, 1917, “found Doug [Stier], Ham and I had been transferred to 61 T.S. for flying. Great Excitement!!!” (61 T.S. was also at South Carlton, and they did not need to change quarters.) Stier and Hamilton “went up in the afternoon in an Avro and were awfully discouraged.” On New Year’s Day, Milnor wrote in his diary: “Had my first flip in an Avro at 3:30 with Lt. [Charles Hurd] Howell an American in the R.F.C. I was greatly surprised in the difference between the ‘joy stick’ control and the ‘Scissors’ control in a ‘Rumpety.’ I was absolutely lost and had much ‘wind up’ and couldn’t fly for mud. We did a spinning nose dive, loop and vertical banks. I was horribly dizzy. The only thing that seemed easy was landing.”

When flying the next day, Milnor was again dizzy and felt sick, and the following day wondered whether his feeling “punk” was related to the smell of the castor oil used to lubricate airplane engines. “Doug and Ham both went solo and are very confident. I am afraid they will get so far ahead of me that I won’t be able to catch them.”26 On January 4, 1918, he “Went up to see the M.O. who said I had influenza (the pet sickness over here).” (This was not “Spanish flu,” which did not reach Europe until later in the year.)

Milnor did not try flying again until January 13, 1918, when “it made me sick as before—damn the luck. Howell came over to the room and advised me to give up flying. He wrote to Dwyer and to a friend of his in regard to me, suggesting a commission as a machine gun instructor. I also wrote Dwyer asking for advice. . . . I am horribly disappointed about my flying and am wondering what will happen to me and if I will get a commission.”

A few days later Milnor wrote “an official letter asking for a ground job in the AS. SC. [Aviation Service, Signal Corps]” and learned the next day that he had been scheduled for a medical board (exam): “It seems you can’t give up flying without one even when only attached to the R.F.C.”27 Whilst waiting for the medical board—and having recently attended the funeral of fellow second Oxford detachment member Joseph Hiserodt Sharpe—Milnor witnessed two fatal crashes at South Carlton. The first was that of Andrew Rushworth Ward: “Went out on the Aerodrom [sic] and saw Ward go up in a D.H.V. never to come down alive again. He was simply plain murdered.”28 Then on January 27, 1918, “There was a terrible crash at 2:00. [Evanda Berkeley] Garnett and [Allan Barrie] Johnson an M.C. crashed just outside our hut. Johnson was burned to death in the machine and Garnett was horribly burned but got out in some way.” Garnett died late that evening.

The next day Milnor learned that his medical board would take place on February 7, 1918; he was able to talk by phone to Dwyer, who was at nearby Waddington, but Dwyer was not encouraging: he “gave me no hopes for a ground job. Said it was either France as an A.M. [airplane mechanic] or home.”29 Two days before the medical board, Milnor and Theose Elwyn Tillinghast, who was also at South Carlton and who evidently was going to bat for Milnor, walked over to the 4th Northern General Hospital in Lincoln where an American M.D. examined Milnor’s eyes and opined that they “were ‘over active’ and might cause my sickness in the air.”

On February 6, 1918, Milnor took the train to London. The next day he had an encouraging encounter with Dwyer at American Aviation H.Q., recently relocated from the Goring Hotel to nearby 35 Eaton Place,30 and, at his medical board, learned that he would need to go out to Hendon aerodrome on the northern outskirts of London for a trial flight with a medical officer. Thus, on February 8, 1918, he “had a test flight with an M.O. in a DH.VI. It made me quite sick, as before, so he advised me to ‘chuck’ flying. Said I was organically O.K. but simply not built for flying.” This was just over a month after Milnor had been diagnosed with influenza. Given that he was demonstrably a good sailor and had flown Rumpties without ill effect prior to his bout of flu, I wonder whether his air sickness was related to the flu, which can affect the inner ear—and whether he might have gotten over it given time. But this was never tested: Officially he was declared unfit for flying until his next medical board, but Milnor himself was “ready to wash out.”31

Milnor returned to South Carlton, where he spent the rest of February, and bad news kept coming. Stier, now training on DH.4s at Waddington, phoned Milnor on February 12, 1918, to tell him that Stillman had had a bad crash. On the 19th he learned that Lindley Haines De Garmo of the first Oxford detachment and Donald Elsworth Carlton of the second had been killed in crashes, and a few days later that Stillman had died.

On February 26, 1918, Milnor “Had a letter from London saying I would be ordered there for assignment to duty. Hope it means a job at [American Aviation] H. Q.,” and on March 3, 1918, “Orders came in the mail for me to report to London to-morrow.” Hamilton turned up at South Carlton unexpectedly, also bound for London, so they were able to travel together.

London, American Aviation H.Q.

Milnor reported to American Aviation H.Q. on his arrival in London on March 4, 1918. He met with Dwyer the next day, who told him he “was to be a Machine Gun Instructor.” As the days passed Milnor made himself useful at H.Q., taking over “all the work in regard to the commissions so I will have plenty to do.”32 (Dwyer had previously remarked on the accuracy of reports submitted by Milnor.33) There was evidently no further mention of machine gun instruction, but in May Henry Theodore Fleitmann of the personnel office told Milnor that he (Milnor) and a colleague would “probably be wanted as Equipment officers with squadrons for overseas as soon as our commissions come through and Dwyer can spare us.”34 Two weeks later, the word was that they would be “wanted as Equipment Officers with a bombing Squadron in about a month.”35 Soon thereafter Milnor was left “in charge” when Dwyer went to Turnberry.

Meanwhile, Milnor’s relationship with Dwyer—who could evidently rub people the wrong way36—was growing more relaxed, and the “Lt. Dwyer” of Milnor’s earlier diary entries becomes “Geoff.” On June 17, 1918: “Went around to Geoff’s apartment from Murrays and I had quite a talk with him about our future work. It looks now as though I was going to stay here as his assistant for good.”

It was a relief to Milnor that, although no longer training to fly, he did get his commission. When he thought he would be a machine gun instructor in early March, he filled out the necessary application to be sent to Pershing; two weeks later “My application came back from Tours owing to some small mistake. Makes me sick.”37 However, in early April, “A cable came through from France saying all cadets in England were to be recommended, so we all were. As my papers were still here in the office my name went in the cable.”38 Pershing had been made aware that, due to insufficient training facilities, many would-be pilots in England were falling behind their stateside counterparts in gaining commissions, and he was recommending to Washington that the affected men receive commissions as first lieutenants aviation reserve; Washington agreed, provided the men were put on “non flying” status and only transferred to flying status when they completed training.39 Milnor was among those granted their commissions on this basis, as recorded in a cablegram dated May 13, 1918.40 He was among the those whose status would not be changed from “non-flying” to “flying.” He noted with some relief in his diary on May 27, 1918 that “Active duty orders arrived about 3.30. Some good news. So I am now a full fledged 1st ‘Lute’.”40a

When he arrived in London, Milnor found that Stokes—who had been sidelined by an operation when most of the other second Oxford detachment men were going to Grantham—was working at Aviation H.Q. Stokes sent Milnor “around to the Red Court Hotel, 19 Bedford Place where he and Capt. Swann are staying.” Three days later “ [I] brought my luggage out to the hotel. Jim & Capt. Swann have left to take an apartment so I moved into Jim’s old room No. 18 on the ground floor.”41 Russell Square and the Red Court Hotel were a bit of a hike from H.Q., and this may have prompted Milnor to go in with Stokes on an apartment on Ebury Street in Belgravia in early July, when it was clear his position at H.Q. was secure.

Milnor’s days in the office at 35 Eaton Place could be monotonous. The tedium was offset by encounters with Oxford detachment members passing through London. At various times Milnor saw and/or dined with Harold Hatch Gile (“Hash”), Duerson Knight, Bennett Oliver (“Bim”), Stuart Cary Welch, Paul Stuart Winslow, and William Dolley Tipton (“Tip”) of the first Oxford detachment. Of the second Oxford detachment men, he saw Earl Adams, Mudge, Ritter, and Wheeler, all of whom had been at O.S.U., as well as Wendell Ellison Borncamp, Walter Chalaire, Goodnow (“Goody”), John Warren Leach, Conrad Henry Matthiessen (“Matty”), Francis Kinloch Read (“Frank”), the two “Jakes” (Walter Andrew Stahl and Julian Carr Stanley), and Raymond Watts. His good friend Stier dropped in on his way out to Stonehenge for training in March and then spent his embarkation leave in London with Milnor in the latter part of May. Hamilton, who had been posted to France in March, had leave in July and spent it with Milnor.

Towards the end of August, second Oxford detachment member Finley Austin Morrison (“Morry”), who had been injured flying with No. 74 Squadron, R.A.F., turned up in London: “[he] has had to wash out flying. He has had a talk with Capt. Foster and is going to be under him. We are going to try and get an apartment together.”42 On the first of August the woman who owned the flat Milnor and Stokes were renting had “returned unexpectedly but is going to let us have the two upstairs rooms.” Also, at some point, Stokes, who had trained as a lawyer, left Aviation H.Q. to take a position in the Judge Advocates General Department, and this may have contributed to Milnor’s desire to find a new place to live. Milnor and Morrison soon found a flat “directly across the street from the one I’m in,” thus evidently also on Ebury St., but it wasn’t until the middle of September 1918 that Milnor moved in.43

Meanwhile, a particularly welcome visitor finally surfaced in London. Milnor’s sister, Dorothy Semmes Milnor, was married to Charles Talley Blackburn, nicknamed “Black.”44 He was the commanding officer of the Navy destroyer U.S.S. Beale, which periodically docked in Liverpool. He was finally able to come down to London just as Milnor was moving into the new flat with Morrison, and Milnor put him up there. On September 16, 1918, “Office till 1:00 when Black came in and he, Geoff, Morry and I had lunch at the canteen. We stopped at the flat on the way back and found six bottles of real Scotch had arrived, so we promptly sampled it. Office till 6:30. . . . Back here and sat talking till 1:30. Black made up a long list of things to eat that he is going to send us from Liverpool. It sure is wonderful to have him here with us and seems quite like old times.” Blackburn would visit Milnor again in October 1918.

Milnor’s work in London put him in a position to hear of casualties among the members of the Oxford detachments. On April 17, 1918, he learned that Sandford (“Sandy”), with whom he had trained at Tadcaster, was missing.45 A few days later he was given the grim task of going “to Henley to identify poor Tom Mooney who was burned in a R E 8”; Thomas F. Mooney was a member of the first Oxford detachment.46 On April 26, 1918, Milnor noted “Report that Stanberry [sic] has been killed”; Elwood D. Stanbery was in the second Oxford detachment. In May Milnor heard that “Alex Hammer” and “Dickie Mortimer” were missing or killed, presumably Earl Marschutz Hammer and Richard Mortimer, both of the first Oxford detachment. On June 22, 1918: “Mac Grider is missing.” The worst news for Milnor came towards the end of the summer. On August 27, 1918: “Ham unofficially reported missing but I don’t believe it, “ and then, on September 4, 1918: “A very bad day. Old Ham was officially reported missing and so was Tip. Ham was brought down from the ground so I’m afraid there isn’t much hope for him. It’s taken the life out of me. . . . Terrible gloom in the office.” (Tipton survived; Hamilton did not.)

Milnor also learned about fellow detachment members in hospital in England and, just as he had back in November 1917 when he visited Whidden in hospital, he made it his business to check on them. Shortly after reporting to HQ in March he “Went out to Tooting to see Kerk who is in hospital there”; Kerk was probably in Grove Military Hospital in Tooting, some way south of the Thames.47 On April 27, 1918, Milnor “Went out to Hampstead to see Bostick who is back from France as result of a terrible crash.” Bonham Hagood Bostick had been admitted to the R.A.F. Central Hospital in Hampstead a few days previously; Milnor’s diary records another visit to Bostick in early June 1918. In early July, Milnor noted that “Went out to the hospital in Regent’s Park to see Leach who is back from France wounded. Got an explosive in the shoulder which came out the back of his neck. Poor chap he is suffering pretty much and they are afraid of [sic] his arm.”48 The afternoon of August 15, 1918, Milnor “Went out to Dartford . . . to see Chalaire who was wounded. . . . He is doing splendidly. Bullet through the leg.” It was good news when at the end of July “Bostick dropped in to see us”; on September 11, 1918, “Leach and Chalaire came in the office after lunch. Both are doing very well.” Leach continued ambulatory, but about ten days later Milnor noted “Luncheon with Leach at the canteen. Poor chap, his arm doesn’t seem to get much better and he is still in a plaster cast.”49

Milnor made several trips out of London on business and pleasure. The first had been to what I assume was Henley-on-Thames, west of London, when Tom Mooney crashed and died while ferrying an R.E.8. In early June 1918 Milnor accompanied two new cadets to Oxford and took them to report to the commandant of the School of Military Aeronautics, Bertram Richard White Beor; he also saw Gerald Graham Adeley, assistant commandant, as well as Dud Mudge.50 A week later Milnor went up to Lincoln, apparently to check on men recently posted to South Carlton and Waddington, while also taking the opportunity to visit with friends.

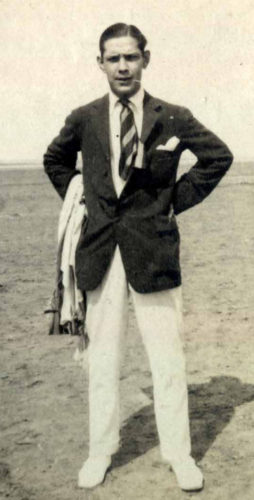

When he had a week’s leave in August, he spent it in Southport, a seaside resort town, which he chose in part because of its proximity to Liverpool where he hoped he might encounter his brother-in-law. Returned to London on August 27, 1918, he found that “Dwyer has shoved all the handling of the Handley Page work over to me.” Handley Pages were bombers, huge planes for the time, built and used by the British. The American air service wished to develop night bombardment squadrons and entered into an agreement with the British that involved manufacturing the component parts of this type of plane in the U.S. to be shipped for assembly to Great Britain, where American pilots would train on them. Assembly and training were to take place at sites on the southeast coast of England near Chichester, notably Ford Junction, where the school at No. 1 Field was opened in mid-August 1918.51 Milnor’s next trip out of London was thus to Ford Junction “to get a line on the work there.” “Just at present they only have a few B.E.s and Farmans but they manage go get along fairly well with these. They will have to til the H.P.s begin to arrive” (only one did before the war ended).52

Milnor made more trips to the south coast, but these were for pleasure, to visit the Cook family—Morton Lewis Cook and his wife Kate Cook, née Stancombe—who had befriended Milnor’s flatmate Morrison. The Cooks visited Morrison and Milnor in London and welcomed them to their home in Shoreham. In fact, the day Milnor returned to the flat from Ford Junction, he “Found Mrs. Cook, Morry’s ‘adopted’ mother there. She very kindly sewed on my two service chevrons for me.”53 Mr. Cook owned Cook’s Jam Factory, evidently a very successful business, and Mrs. Cook excelled in domestic skills, very much living up to her married name. From Milnor’s account of meals at “Campsie” (the name of the Cooks’ house) during his first quick visit to Shoreham in early October 1918, one would not know there was a war on. On another visit towards the end of the month, Milnor enjoyed a tour of the jam factory and visited the two Cook boys at their boarding school.

On November 1, 1918, a few days after returning from Shoreham, Milnor made an extensive entry in his diary beginning “Great surprise today. [Robert Alexander] Anderson, [John Owen] Donaldson and Tillinghast all came in the office this morning looking like ‘nothing on earth.’ All three had just come over from Holland after having escaped from a German Prison. . . . Tilley was my C.O. at So. Carlton and Andy came over with the big bunch in Sept. ’17. Donaldson was one of the later crowd that came over as officers. They are the first American flying officers to escape.” Whether formally or otherwise, the three men were debriefed, and Milnor wrote down a detailed résumé of their tale in his diary, anticipating the accounts later published by Anderson and Donaldson.54 “The three boys are now in London under orders from the attaché here and are waiting to hear Gen. Pershings decision on what they are to do.”

On November 7, 1918, Milnor and Morrison went to Liberty’s department store “at lunch time and bought some beautiful scarfs to send home for Christmas presents. Leach is taking them for us. We had a wild rumor about 4:00 that the armistice had been signed but no one could get any official ‘dope’ on it.” It looked the next day as though the scarves-for-Christmas plan would come to naught when “Warren Leach came in during the afternoon and said they were not going to let him go home until his wound healed. It’s a damn shame, I think.” Late the evening of November 10th “News came that the Kaiser and Crown Prince had abdicated, . . . and there was a good deal of cheering.” The next day Milnor wrote extensively in his diary about the armistice. “Gen [John] Biddle cancelled all work for the day,” and Milnor joined in the celebrations, making his way with the ever-swelling crowd to Buckingham Palace where he saw Churchill arrive and watched as the king and queen appeared on the balcony in the early afternoon: “And the crowd went wild.”55 Milnor ends his diary entry that day with the modest hope that “it won’t be so very many more months before I will be home.”

Returning home

At the office on November 12, 1918, where “no one seemed to feel like work,” a “Cable came from General [Mason] Patrick saying to close up all work that was incurring expense, as soon as possible. . . Lord but I hope they clean out England right away.” On November 15, 1918, there was a “Confidential report from Admiralty that they had enough ships in port now to take back all troops in England. . . .” After some uncertainty as to whether he would be required to remain at H.Q., and with help from Dwyer, Milnor learned that he would “leave for Liverpool about Saturday.”56 He made a hasty trip to Shoreham while Dwyer arranged “a stateroom on the first boat” for him and, back in London, made it his business to get “one of the plates of Fred’s pictures for Mr. Stillman.”57 On returning to the office he found “Paul [Stuart Winslow?] had called up to say there was no room for me on the Lapland and not to come down [to Liverpool] till to morrow.”

Paul’s information turned out to be incorrect, but by the time Milnor arrived at Liverpool with Frank Read on November 21, 1918, he found the booking on the Lapland, which sailed the next day, had been cancelled. He ran into Chalaire, and together they were able to get on a priority list for the next ship, the Mauretania, and they, along with second Oxford detachment members Anderson, Bostick, Raphael Sergius De Mitkiewicz, Gaipa, Lawton, Mudge, Read, Homer Ireland Smith, and Lynn Lemuel Stratton—as well as Leach, in a detachment of “Casual sick”—set sail on November 25, 1918. Though it sailed later, the Mauretania beat the Lapland home by two days, arriving December 2, 1918, to much publicity. It was, after all, the first ship carrying American soldiers and aviators from Europe to arrive back in the U.S. after the war.58

Milnor settled in Ridgewood, New Jersey, and resumed his work as a bond broker.59

mrsmcq June 29, 2020; extensively revised based on diary, September 15, 2020

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Milnor’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Mr Joseph K Milnor. The place and date of his death are taken from “J. Kirkbride Milnor.” The photo is from Milnor’s photo album. This and other photos on this page, unless otherwise noted, are courtesy of Jay Milnor, who has the album, with thanks to Mike O’Neal for reproductions.

2 Information on Milnor’s descent is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com. On his father, see “Lloyd Milnor.”

3 Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Joseph K Milnor (and family).

4 Private communication from Jay Milnor. On Lloyd Milnor’s education, see A History of the City of Chicago Its Men and Institutions, p. 269.

5 See his draft registtration, cited above.

6 “Here and Hereabouts” June 28, 1917.

7 “Here and Hereabouts” July 19, 1917.

8 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

9 Milnor, diary entry for September 19, 1917. Unless otherwise noted, most of the following account is based on Milnor’s diary; quotations from the diary are footnoted when the date of the entry might not otherwise be evident.

10 Milnor names his roommates in his diary entry for September 18, 1917.

11 Milnor, diary entry for September 21, 1917.

12 Milnor, diary entry for October 2, 1917. This is one of at least four explanations for the change of orders; see also those supplied by Hamilton Hadley on p. 4 (286) of “Foreign Aviation Detachments”; by Geoffrey Dwyer on p. 2 of “Report on Air Service Flying Training Department in England”; and by Claude E. Duncan as recorded in Sloan and Hocutt, “The Real Italian Detachment,” p. 44. Samuel Hynes remarks in his study of American flyers in World War I: “Eagerness plus belatedness equals muddle, and muddle would be the condition of the U.S. Air Service, its training program and its squadrons, throughout the war” (The Unsubstantial Air, pp. 39–40).

13 Milnor, diary entry for October 2, 1917.

14 Milnor, diary entry for October 7, 1917; Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of October 7, 1917.

15 Milnor, diary entry for October 8, 1917.

16 Milnor, diary entry for October 22, 1917.

17 Grider, in his diary entry for November 6, 1917, wrote that “Poor old Jim Stokes is in the hospital at Oxford for Hernia.”

18 Milnor, diary entry for November 16, 1917.

19 Milnor, diary entry for November 14, 1917.

20 [Cushing], The Story of U.S. Army Base Hospital No. 5, pp. 46–47.

21 On this hospital, see “American Red Cross Military Hospital No. 22.”

22 On Whidden, see Carlisle, A Seven Years’ Record of the Society of Alumni of Bellevue Hospital, 1915-1921, pp. 17–19.

23 Milnor, diary entry for November 17, 1917.

24 This probable identification of Milnor’s “Ross-Hume” is based on a private exchange with Great War Forum member quemerford, who was able to supply a copy of P. G. Ross-Hume’s R.A.F. service record. There are (undocumented) statements associating P. G. Ross-Hume’s older brother, Alexander Ross-Hume, with No. 14 T.S. in 1917, but this does not appear to be borne out by the latter’s R.A.F. service record. Milnor’s description of his C.O. in his diary entry for November 21, 1917, seems to be a mix of fact (P.G. Ross-Hume had been awarded the M.C.) and inaccurate hearsay: I find no reliable source associating either Ross-Hume brother with Immelmann’s death, and both were older than “24,” their birth years being 1884 (Alexander) and 1888 (Percy Gilbert).

25 Milnor, diary entry for November 22, 1917.

26 Milnor, diary entry for January 3, 1918.

27 Milnor, diary entry for January 19, 1918.

28 Milnor, diary entry for January 21, 1918.

29 Milnor, diary entry for January January 28, 1918.

30 Murray, Air Service History, p. 80 (4).

31 Milnor, diary entry for February 8, 1918.

32 Milnor, diary entry for March 9, 1918.

33 Milnor, diary entry for February 7, 1918.

34 Milnor, diary entry for May 11, 1918. I have not been able to identify his colleague, to whom he refers her and elsewhere simply as “Pat.”

35 Milnor, diary entry for May 24, 1918.

36 Both Clements and Foss express dislike of Dwyer in their diaries, and on different occasions Milnor describes him as “quite disagreeable” (diary, January 28, 1918) and “terrible to work under at times” (April 12, 1918). Some of the bad feeling may have been related to Dwyer’s difficult liaison position between the British and the Americans and to his being the face of the bureaucratic “muddle” of war time.

37 Milnor, diary entry for March 18, 1918.

38 Milnor, diary entry for April 2, 1918.

39 On non-flying status, see cablegrams 726-S and 955-R.

40 Cablegram 1303-R.

40a See also McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 147,” regarding Milnor’s active duty status.

41 Milnor, diary entry for March 4, 1918.

42 Milnor, diary entry for August 28, 1918. I have not been able to identify Capt. Foster beyond his initials, P.L.

43 Milnor, diary entries for August 30 and September 15, 1918.

44 I am grateful to Jay Milnor for identifying “Black.”

45 Milnor learned the same day that Gustav Hermann Kissel, who had been at Ayr at the same time as Hamilton, was also missing. Both Sandford and Kissel were later confirmed dead.

46 There is a cryptic person casualty card for Mooney (“Mooney, T.F. (Thomas F.)”), which records only that he was killed April 22, 1918. The more informative incident casualty card for some reason gives his name as “A. M. Mooney” (“Mooney, A.M.”).

47 Milnor, diary entry for March 8, 1918; records related to Kerk show him taken off flying for a period, but don’t indicate why.

48 Milnor, diary entry for July 8, 1918.

49 Milnor, diary entry for September 23, 1918.

50 Milnor, diary entries for June 3 and 4, 1918. Milnor mentions meeting “Mrs. Brown and her daughter who are Canadians”; see Hooper, Somewhere in France, notes to letter of October 27, 1917, continuation on October 30, 1917, for possible identification.

51 See Night Bombardment Section, Air Service, A.E.F., England; and the succinct summary on pp. 120–22 of Fisher, The Development of Military Night Aviation to 1919.

52 Milnor, diary entries for September 18 and 19, 1918.

53 Milnor, diary entry for September 19, 1918.

54 Anderson’s story was published in installment in McClure’s in August 1919–February 1920; Donaldson published two accounts, “Escaping from Two German Prisons” and “My Capture and Escape.”

55 Milnor’s diary entry for November 11, 1918, courtesy of Jay Milnor.

56 Milnor, diary entry for November 17, 1918.

57 Milnor, diary entry for November 20, 1918.

58 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for casual officers, Air Service, on Mauretania.

59 Ancestry.com, 1940 United States Federal Census, record for Joseph K Milnor.