(Derby, Connecticut, March 20, 1896–Los Angeles, September 15, 1975)1

Oxford & Gratham ✯ No 38 Squadron ✯ Waddington ✯ Marske, Chattis Hill, C.D.P. ✯ With the I.A.F.

Payden was of Irish descent. His father, Thomas E., and his grandfather, John, who emigrated to the U.S. in about 1855, spelled their last name “Paden.” Thomas E. Paden was a tool maker employed for a time at the Birmingham Iron Foundry in Derby, Connecticut. In 1895 he married Jennie McCabe, whose parents had also emigrated from Ireland, and the next year Joseph Raymond, their only child, was born. The 1910 census shows Thomas residing and working as a tool maker in South Bend, Indiana, while Jennie and their son remained in Derby. Whether Thomas was seeking better prospects for his family or there had been a parting of the ways cannot be determined; he died in South Bend the next year. Joseph Raymond Payden was well endowed with aunts on his mother’s side, and he and Jennie resided with one of them while Jennie earned a living clerking in a clothing store.2 Payden attended high school in Derby, graduating with honors in 1915.3 He then began his studies at nearby Yale University, enrolling in Sheffield Scientific School to study engineering.4

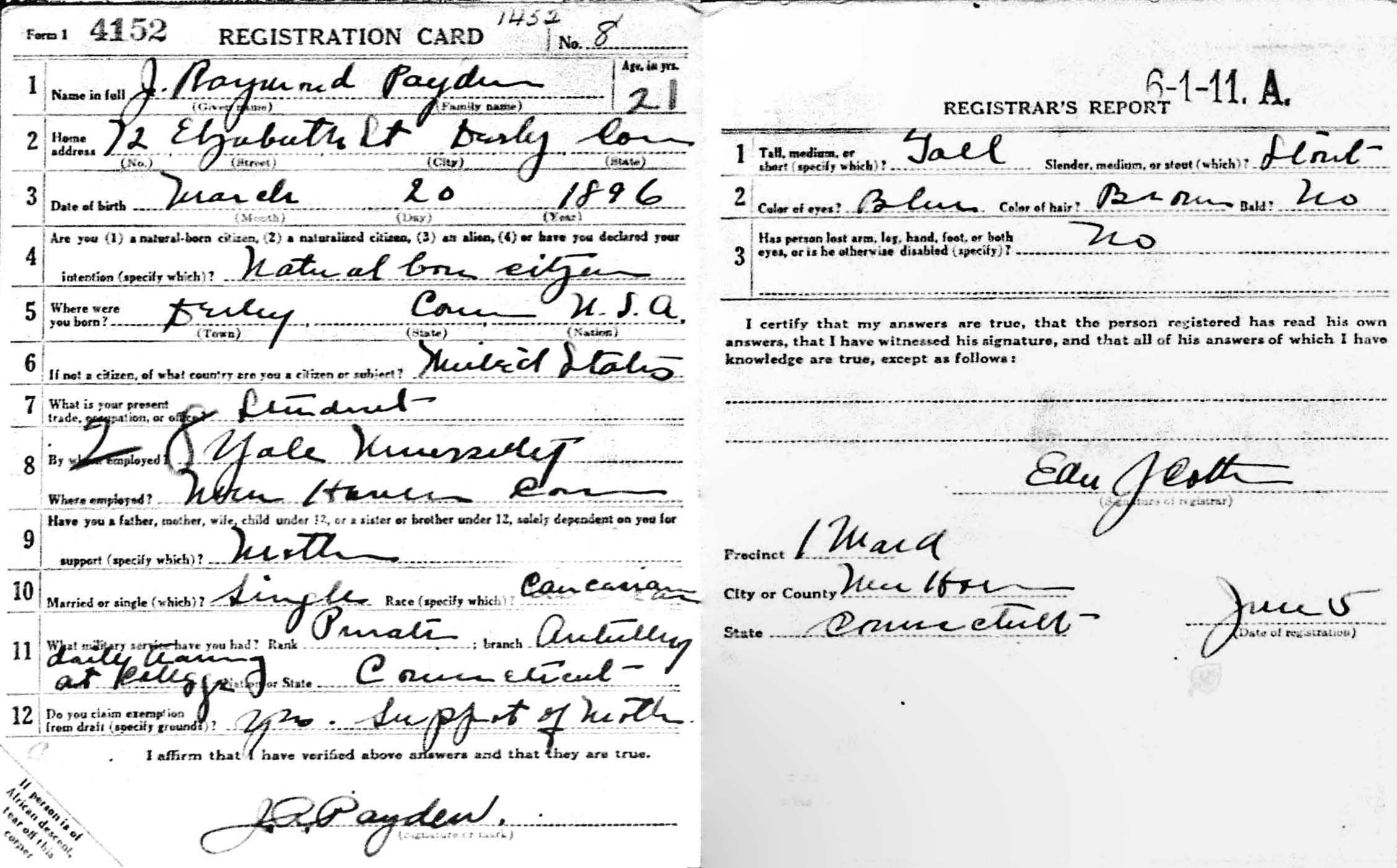

In connection with his high school graduation, Payden had written an essay titled “One Hundred Years of Peace” in which he expressed the hope that the U.S. would not be drawn into the war. 5 Over the next two years his views evidently changed. When he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, he noted that he had had daily military training at college.

Shortly thereafter, despite having claimed exemption from the draft because he was supporting his mother, Payden applied for and was accepted by the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. This meant interrupting his engineering studies, but universities during this period were supportive of men taking part in the war effort and accommodated them. By the end of June 1917 Payden was enrolled in ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; his class of approximately thirty-four men graduated on August 25, 1917.6

About a third of the men from this M.I.T. ground school class, including Payden, chose or were chosen to do their next training in Italy. After some free time, during which many of the men visited home, Payden and the others expecting to train in Italy gathered at Mineola on Long Island. On September 18, 1917, they were ferried to the west side of Manhattan to board the Carmania at a Cunard pier in the Hudson River. They sailed initially to Halifax. From there, on September 21, 1917, the Carmania set out as part of a convoy to cross the Atlantic. The 150 men of the detachment travelled first class and had plenty of leisure, apart from submarine duty towards the end of the voyage and daily Italian lessons given by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them.

Oxford & Grantham

It was thus a surprise when, on docking at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the members of the “Italian detachment” learned that they would not continue to Italy, but would remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford. There was some grumbling, but the men fairly quickly settled into rooms at Christ Church College and The Queen’s College and life at Oxford. Payden was among the ninety men housed initially at Christ Church. After a bibulous celebration by members of the first Oxford detachment (who had arrived at Oxford a month before the second) along with a few members of the second, irate British authorities insisted that all the Americans be housed in the same college. Thus, on October 22, 1917, everyone moved to Exeter College. 7 They were also ordered to purchase spiffier uniforms which included Sam Browne belts, and to exchange their American campaign hats for R.F.C. caps.

Payden’s roommate at Oxford was Roy Olin Garver, a cadet from Illinois who had attended ground school at Ohio State University.8 Payden took several pictures of Reuben Lee Paskill at Oxford, so it seems likely that the two of them palled around together there—they had probably been roommates on the Carmania, as men had apparently been assigned to state rooms in alphabetical order.9

After a month, on November 3, 1917, twenty men from the detachment learned they would start flying training at Stamford, but the others, including Payden, were sent north to take a machine gunnery course at Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire. As Parr Hooper, also sent to Grantham, remarked, “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”10

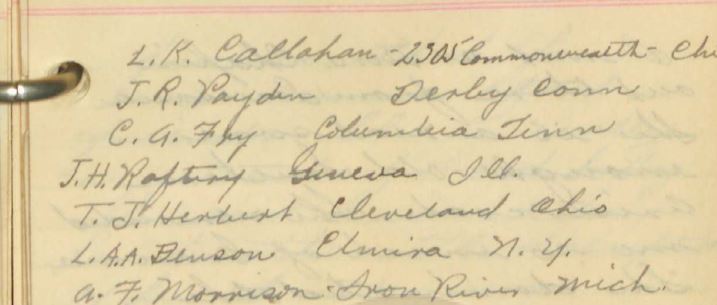

The men were assigned to huts at Harrowby Camp, and Payden shared his with Leslie Alfred Amzia Benson, Laurence Kingsley Callahan, John Hurtman Fulford, Clarence Horne Fry, John McGavock Grider, Thomas John Herbert, Finley Austin Morrison, and John Howard Raftery.11

No. 38 Squadron

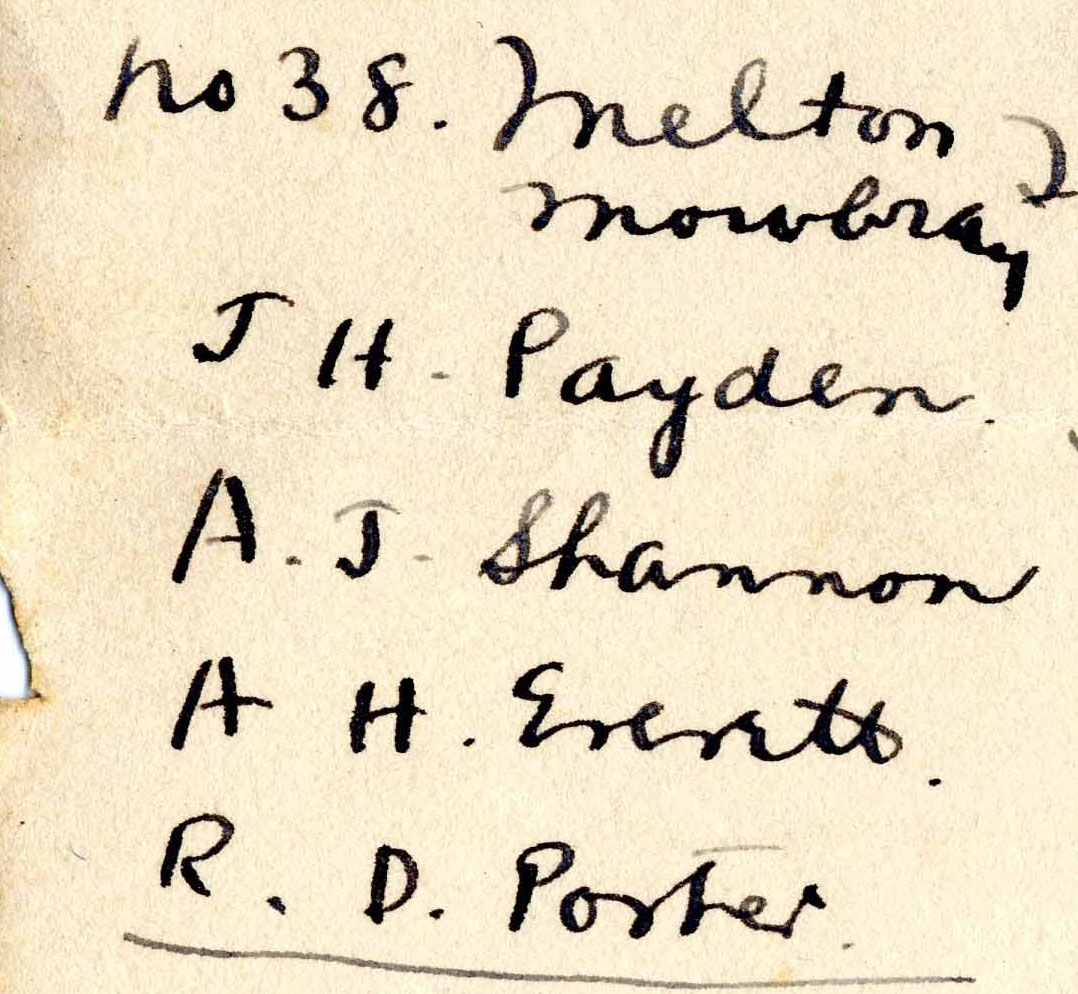

At last, on December 3, 1917, the Grantham men were posted to flying squadrons. Payden, along with Albert Frank Everett, Robert Brewster Porter, and Andrew Joseph Shannon, was assigned to No. 38 Squadron.14 Another photo kept by Payden shows himself, along with Everett, Porter, and four English officers, at No. 38, which was a home defense squadron, tasked with defending the West Midlands from Zeppelins. At the end of 1917, the squadron was flying F.E.2b’s and F.E.2d’s, two-seat fighter and bomber biplanes—not suitable for primary flight training, but the cadets could certainly have gone up as passengers. Headquartered at Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire, the squadron’s three flights operated out of Leadenham, Buckminster, and Stamford; the second Oxford detachment men probably spent most of their time at one of these sites.15 Payden retained photos of a crash landing made in early January 1918 by Edward Frank Wilson, who was on a training flight in an F.E.2b out of Stamford, and this suggests that Payden may have been with the 38 Squadron detachment at Stamford.16 Also indicating his presence at Stamford are a card Payden kept announcing a dance at the Drill Hall in Stamford on December 26, 1917, and two photos of a snowball fight that he captioned “H[ome] D[efense] Stamford.”17 There was probably some travel back and forth between Stamford and Melton Mowbray: this is suggested by an R.F.C. whist scoring card with the printed place and date: “Melton Mowbray, December 31st 1917.”18

Waddington

Quite a number of men from the second Oxford detachment were reassigned on January 25 and 26, 1918, including some who, like Payden, had been parked at squadrons where training opportunities were minimal. Along with William Thomas Clements, Raphael Sergius De Mitkiewicz, Fremont Cutler Foss, Leo McCarthy, Perley Melbourne Stoughton, Arthur Paul Supplee, and perhaps others, Payden relocated to Waddington, a major R.F.C. training center just south of Lincoln, and was assigned to No. 44 Training Squadron there.19 William Ludwig Deetjen, along with Payden’s ground school classmates Don Elsworth Carlton and Walter Chalaire, as well as Payden’s Yale classmate, Julian Carr Stanley, had ten days previously been posted from Stamford to Waddington. Deetjen noted in his diary that around the time Payden arrived that “A whole lot of our bunch came from Stamford and all over. We must number about 30.”20 There were also still some men at Waddington who had been sent there in mid-November from Grantham, including George Orrin Middleditch. Payden kept a photo almost certainly taken at Waddington of Middleditch standing between John Arnold “Jerry” Roth of the first Oxford detachment and Carlton of the second, all in flying gear.

The start of training at Waddington was shadowed by grim news. First, the cadets were aware that their fellow second Oxford detachment member Joseph Hiserodt Sharpe, who had been posted to Waddington in November 1918 with Middleditch and others, had died in an air crash there while flying a DH.6 (a two-seater designed for training) in early January. And soon after Payden’s arrival at Waddington, word came that his Oxford roommate, Garver, had been killed. Details were lacking or inaccurate, but Foss’s diary entry for January 28, 1918, shows that news of the death at Shoreham was received at Waddington on the day it occurred.

As noted, Payden was initially assigned to No. 44 Training Squadron. Deetjen wrote that “we learned that 44 T.S. is only a pool squadron. That is where men are held till the upper squadrons are emptied.”21 Some training must have occurred nonetheless, for on February 14, 1918, the day that Payden, along with Foss, De Mitkiewicz, and Stoughton, was reassigned from No. 44 to No. 47 T.S., Payden, according to Foss, “went solo on Longhorn”; he would not have done this without prior experience flying dual.22 And, indeed, Payden kept a photo of a Longhorn and noted (possibly on the back of the photo) that “I had my first flight training on this machine and made my first ‘solo’ 1918 on it. . . .”23

The “Longhorn” was the Maurice Farman S.7, a two-seat biplane that was used for reconnaissance early in the war, but that had long since been relegated to training; the name came from the landing skid extensions that projected out in front of the plane and curved up to hold an elevator. The M.F. S.7 was a “pusher,” i.e., the propeller was at the back, rather than at the front, of the nacelle (which housed the engine and cockpit). Payden’s initial training on a Longhorn was rather unusual, as the elementary flight training plane more often used was the similar, slightly later Maurice Farman plane, the M.F. S.11 “Shorthorn,” often referred to as a “Rumpty” or “Rumpety.” While Payden’s contemporaries (Clements and Deetjen) mention Rumpties and later historians document Shorthorns at Waddington, I have thus far found no mention of Longhorns there other than Payden’s.24

Although I cannot find it explicitly stated, it is apparent that the men who trained at Waddington had been selected to fly two-seat bomber and reconnaissance planes, rather than single-seat scout planes (Clements, who later went on to fly Camels, was transferred away from Waddington when he was selected to train on scouts).

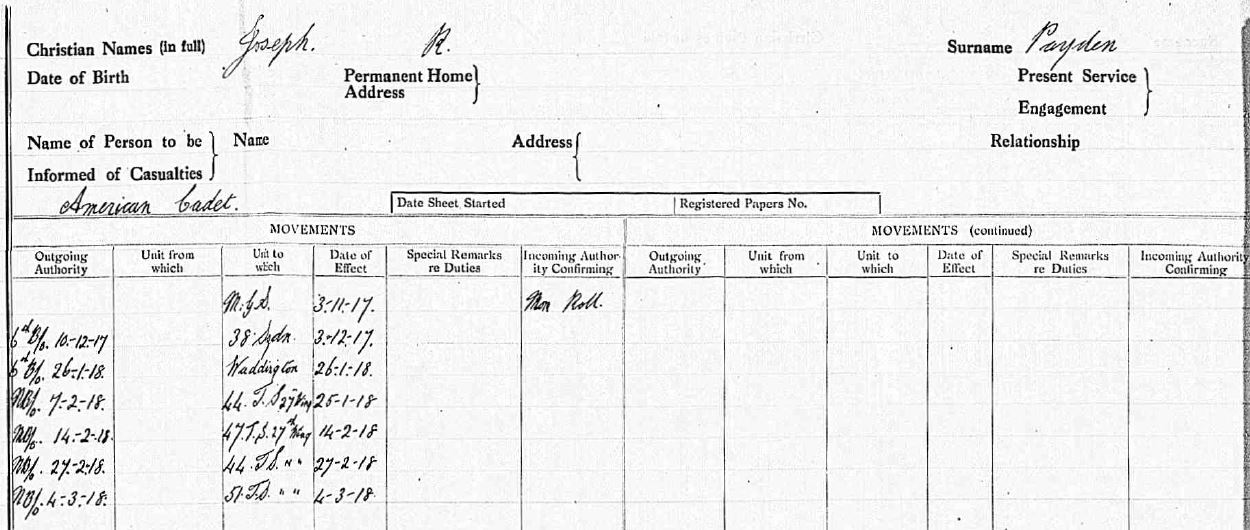

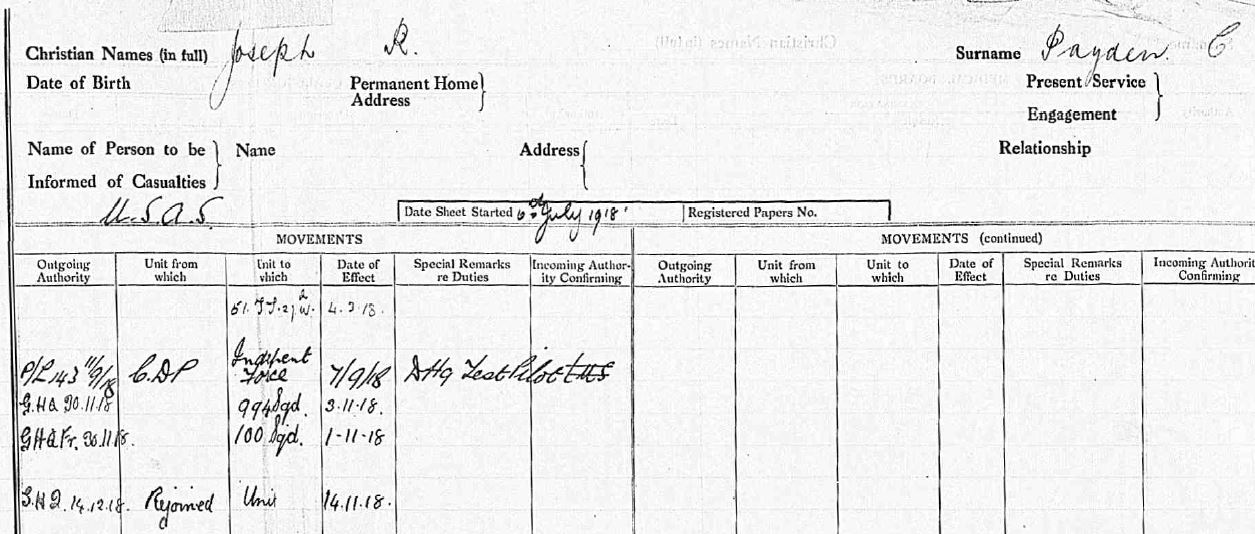

Payden’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card and his Pilot’s Flying Log Book are not extant, so details of the course of his training are lacking. But his training was almost certainly similar to that of Foss, Deetjen, McCarthy, and Coates, all of whom were stationed for a time at Waddington and all of whose training is fairly well documented. After his dual and solo practice on the Longhorn, Payden probably went on to put in many hours on DH.6s, initially dual, and then solo. Payden’s R.A.F. service record indicates that on February 27, 1918, he was once again assigned to No. 44 T.S., from which he was moved less than a week later to No. 51 T.S., still at Waddington.

At 51 he would have overlapped briefly with Deetjen, who wrote that “I am to stunt a deH6 with [instructor Barnard] and then go to BE2E’s.”25 (The B.E.2e was a two-seater originally designed as a bomber and reconnaissance aircraft, by this time obsolete and used for training.) While at No. 51. T.S., incidentally, Payden, like Deetjen, would have encountered the squadron C.O., Lawrence Arthur Pattinson, whom he would surely again encounter when Pattinson was with the Independent Air Force.

During this training period, an incident occurred that Payden recalled after the war. The last German Zeppelin raid on Britain began the evening of April 12, 1918. One of the five airships came inland from the North Sea over the Lincolnshire coast and, shortly before 11 p.m., reached Waddington, which, not having been alerted, was still illuminated. According to Payden, the airship “dropped a large bomb about six feet from the petrol tank at the Waddington station. Fortunately it was a ‘dud’ and failed to explode on contact with the ground.”26

It was almost certainly while Payden was at No. 51 T.S. that he passed the tests required for graduation from the first stage of R.A.F. training (on April 1, 1918, the R.F.C. became the Royal Air Force). Graduation involved clocking a stipulated number of flying hours and passing several tests: making a number of good landings, flying cross country solo, flying at high altitude, and flying on a “service machine”—in the case of Deetjen, Foss, and McCarthy, and probably also Payden, an R.E.8., another two-seat reconnaissance and bombing plane.27

Although not noted in Payden’s R.A.F. service record, he almost certainly was reassigned yet one more time at Waddington, again to No. 44 T.S. Payden kept a travel voucher from when he was “rejoining unit” at Waddington; it is dated May 2, 1918, and stamped by 44 T.S.28 Although Deetjen had described No. 44 as a “pool squadron,” it was evidently where many pilots—Coates, Deetjen, Foss, and McCarthy among them—did their more advanced training after graduation. At 44 they trained on DH.4s and DH.9s, the two-seat bomber and reconnaissance planes they would later fly in France. Payden’s flight on a service machine, qualifying him for graduation thus probably took place at 51 T.S. towards the end of April 1918, prior to his reassignment to No. 44.

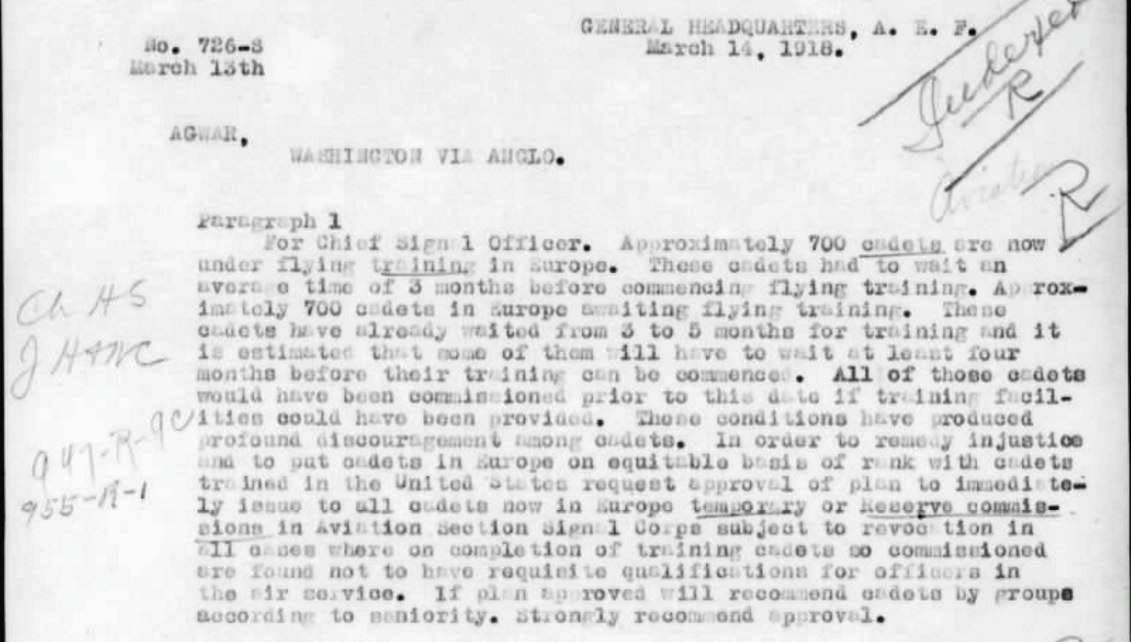

Meanwhile Pershing had sent a cablegram dated April 8, 1918, to Washington recommending that Payden, along with thirty-eight other second Oxford detachment members, as well as many other cadets, be commissioned.29 Pershing asked that they be made “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying.” The “non-flying” status arose from an effort by Pershing to rectify an injustice. In an earlier cable to Washington dated March 13, 1918, Pershing had described the situation of the approximately 1400 aviation cadets in Europe, some of whom had waited three months to start flying training, and some of whom, after five months, were still waiting and might have to wait another four.30 “All of those cadets would have been commissioned prior to this date if training facilities could have been provided. These conditions have produced profound discouragement among cadets.” To remedy this injustice, and to put the European cadets on an equal footing with their counterparts in the U.S., Pershing asked permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .”

Washington approved Pershing’s plan in a cable dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.”31

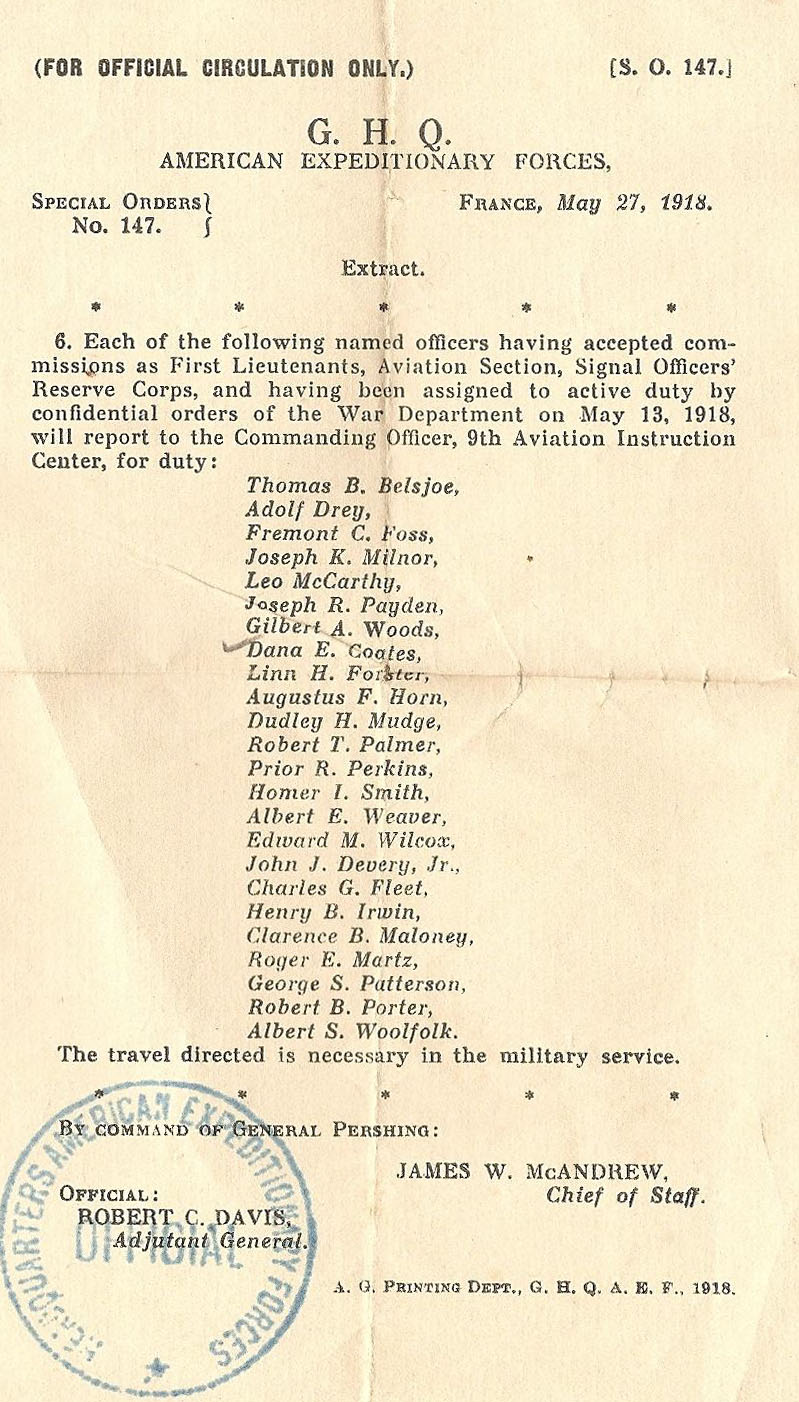

Washington took its time responding to Pershing’s April 8, 1918, cable. On April 30, 1918, an impatient Pershing wrote: “Request action taken on . . .” and lists cables dated March 29 through April 8, 1918.32 The cable from Washington confirming, finally, the commissions requested April 8, 1918, is dated May 13, 1918.33 For Payden and most of the other second Oxford detachment members listed in the April 8, 1918, cablegram, the “non-flying” status was irrelevant, as they had almost certainly qualified by the time word of the May 13, 1918, cablegram from Washington trickled down. Foss and Coates each kept a copy of an extract from Special Orders 147 dated May 27, 1918, that recorded that they, Payden, and a number of others had been commissioned and also placed on active duty.34

As noted, Payden was apparently reassigned by early May 1918 to No. 44 Training Squadron. Coates and Foss did not make this transfer until early June 1918, but, timing aside, Payden’s training was probably similar to theirs. Foss and Coates initially made a number of dual flights in DH.9s before flying DH.9s solo. There would have been landings and forced landing practice, practice firing at a target, bombing practice, formation flying, and a height test—the earlier height test had required flying at 8,000 feet, but now both Coates and Foss record going up to 17,000 feet.

Coates continued training at No. 44 T.S. well into July, but the last flight there that Foss recorded in his Pilot’s Flying Log Book was made on June 20, 1918, and he then evidently had a break from training.35 It seems likely that it was during the latter part of June that he and Payden both obtained leave and travelled around England and Wales together. Payden wrote his mother about the trip, and his letter was published—unfortunately without a date—in a local paper.36 “I have been having ‘some’ time this past week. I obtained a leave and as a result am touring the country a little. Tonight, as you will see by the letterhead, I am in Blackpool . . . I have been through Sheffield, . . . also through Manchester. . . . From there I went to Chester. . . . We next went to Wales, stopping at the town of Wrexham. . . . I made this trip with a fellow chum of mine from New Jersey. He had some friends living at Wrexham. . . .” It is apparent from the caption of a photo kept by Payden, that the “chum of mine from New Jersey” was Foss.37 While at Wrexham, the two of them visited St Giles’ Parish Church, where Payden was able to see the grave of Elihu Yale, the benefactor for whom Payden’s alma mater was named. They went on to Liverpool and thence to Blackpool, where Payden wrote his letter.

In the same newspaper article, a second letter from Payden was printed, this time with a date: July 5, 1918. Among other events, Payden mentions that, about two weeks previously, Prince Albert (later King George VI) “came up to see us” (from Cranwell, about ten miles south of Waddington). “Each of us was introduced to him and he shook hands with all of us.” Also: “On July 1 all the American officers at our place were instructed over to the Duke of Portland’s place. . . . We found that the duke had turned over his place to celebrate Dominion day. This is a Canadian holiday.” Payden appears to recount this with a straight face. Two days after the visit to Welbeck Abbey, Payden travelled down to London, “to see the 4th of July celebration”—the unfortunate nature of what occurred in 1776 again forgotten in Anglo-American amity. Payden’s London travel companion was first Oxford detachment member Edward Milton Wilcox, a “boy from Winsted whom I knew at Yale.”

Payden writes that he and Wilcox left for London on July 3, 1918, and that evening had tickets (stamped “uniform only”—Payden kept his ticket38) to a boxing match at the private National Sporting Club in Covent Garden. The next day they took in the sights and celebrations, and in the evening went to “a show, one of London’s latest. I have now seen about all of London’s best shows”—this suggests that this was but one of a number of trips Payden made to London during his training.

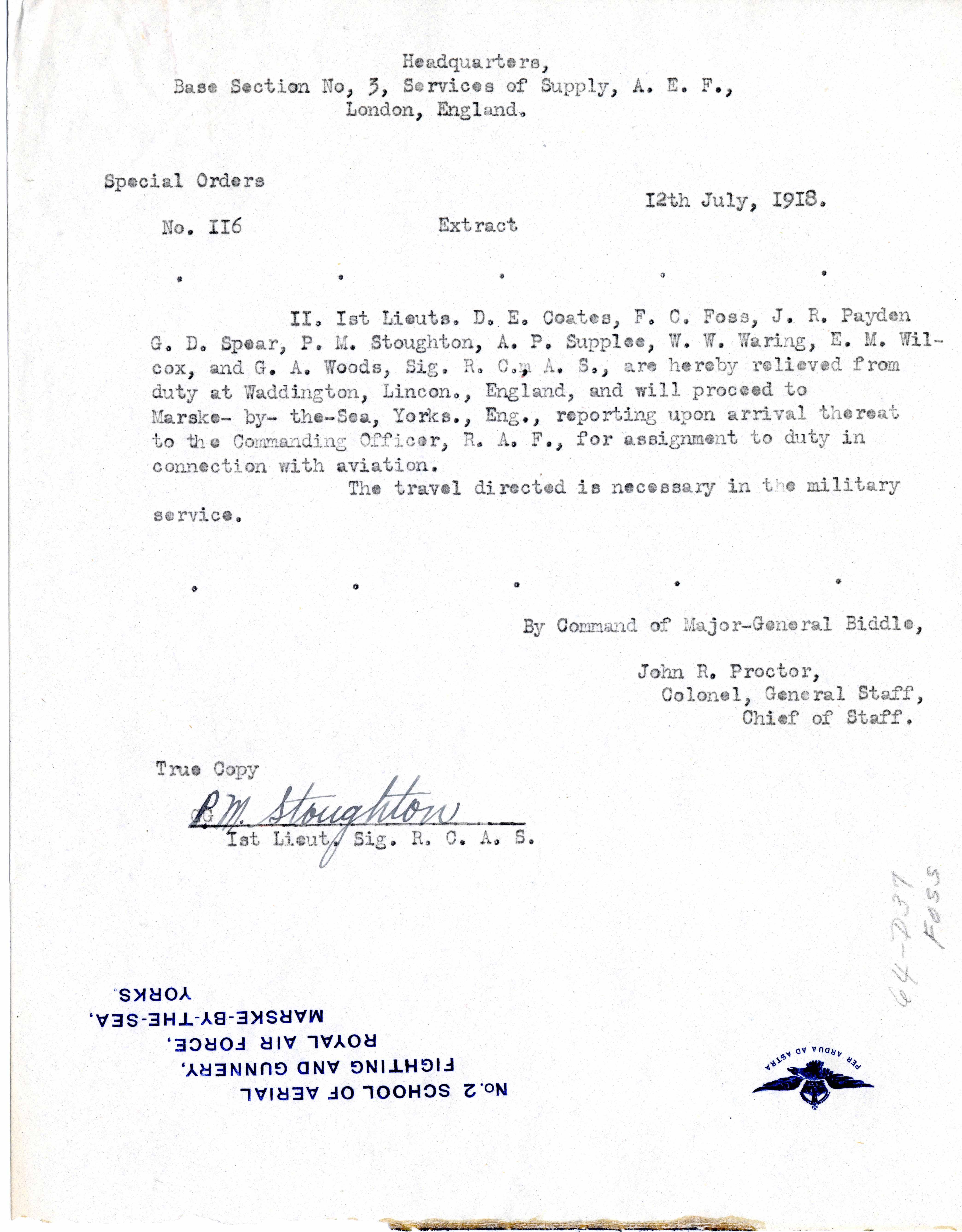

Marske, Chattis Hill, Central Despatch Pool

About a week after returning to Waddington from London Payden and Wilcox, along with Coates and Foss, and several others, were ordered to proceed from Waddington to Marsk-by-the-Sea in northeast Yorkshire where the No. 2 Fighting School was located.39 For a week or so, the men attended classes on the ground, but then took to the air to practice aerial gunnery and fighting. Both Coates and Foss, and thus probably Payden, made their initial flights at Marske as passengers in an Avro, evidently an opportunity for the instructor to check on their flying skills.40 In the case of Foss and Payden, this was a bit ironic, as it appears that neither had flown this basic training plane before. But they quickly moved on to flying DH.9s. In early 1919 Wilcox provided what appears to be an accurate account of his experience for a newspaper article and described how at Marske the men “practiced formation flying, aerial fighting with machine guns located in front of them, synchronized with the propeller blades so that they could dive at another machine or for a ground target and shoot it straight in front of them. They also practiced dropping bombs carrying either two 112-pound bombs or one 230 pounder.”41 In their pilot’s flying log books, both Coates and Foss record aerial fighting with a Camel as their opponent while flying DH.9s.

Somewhere around the end of July 1918, when Foss was ordered to Wiltshire for further bombing training and Coates began ferrying planes, Payden and Wilcox were sent to the Wireless Telephony School at Chattis Hill in Hampshire.42 C. G. Jeffords, in Observers and Navigators, describes how “Experimental work on speech transmission was under way in the UK by May 1915” and notes that field trials in wireless telephony (later known as radio telephony) were undertaken in France in 1917. The Wireless Experimental Establishment at Biggin Hill started training Bristol Fighter and DH.4 and DH.9 crews in January 1918; in early April 1918 the training was “taken over by the newly established Wireless Telephony School which moved to Chattis Hill” around April 15, 1918.43 This technology must have seemed a huge advance over the Morse code transmission and reception the second Oxford detachment members had spent many hours learning and practicing—but it still, as a newspaper account of Wilcox’s experience indicates, required effort and practice. Initially Wilcox and Payden

. . . worked with ground instruments learning the theory of the apparatus. They practiced talking into the transmitter and were instructed how to tune in on the receiving set. [The] wireless telephone, which was just getting perfected when [the war] closed is not like the ordinary phone. One has to hold the [trans]mitter, which is like the [mouthpiece] of an ordinary ‘phone, at an [angle of] 45 degrees and talk in a deep voice and enunciate very [clearly. A] high-pitched voice like a woman’s cannot be heard at all. . . . After three days of ground practice they then took up the aerial practice, receiving and sending messages while in their planes. First Lieut. Wilcox sent messages and Lieut. Payden would receive them and then vice versa. A message could only be sent one way as the person sending a message could not receive one at the same time with the same instrument as in ordinary telephoning. They carried out an aerial drill by telephoning, the sender directing his comrade to turn to the right or left, dip, etc. They could hear messages this way at a distance of five miles and those on the ground having a receiving machine could listen in and check up their movements.44

It is not recorded which planes Payden and Wilcox flew during these practice sessions, although one source indicates that at least two planes Payden was familiar with were available at the Wireless Telephony School, the R.E.8 and the B.E.2e,45 while Jeffords’s account suggests the DH.4s and DH.9s were also flown there. It is worth noting that one of the drawbacks of this newish technology (in addition to the messages being en clair) was the long aerials required. Chattis Hill was also a regular pilot training site, and one historian mentions the “clash between the units using the airfield. Avros and Camels of the [training squadrons] were buzzing round the circuit conflicting with the more staid machines of the Wireless School, which trailed yards of wire behind them”46—which would also be a problem operationally in formation flying and fighting.

Payden kept a railway warrant authorizing him to travel from Stockbridge (the nearest railway station to Chattis Hill) to London.47 It is dated August 5, 1918, which suggests that the course at Chattis Hill was short, while Wilcox recalled that it lasted from July 30 to August 14, 1918.48

Payden and Wilcox reported to the Air Ministry in London, where, on August 14, 1918, they were attached to the Central Despatch Pool R.A.F. as ferry pilots, i.e., they were to fly planes as needed from one station to another within England and between England and France.49 Again there is an account of this work based on Wilcox’s experience:

Every trip was made in a different machine. [Wilcox and Payden] would go to the factory in Bristol, Lincoln or Hendon as the case might be, and fly to Lympne, . . . and there report the machine O.K. or have needed repairs made, and fill up with petrol . . . and oil before making the channel trip. From Lympne they flew across to Marquise, France. It took about 50 minutes to go from one aerodrome to the other. They used their own judgment as to what height to fly at but usually flew at between 3,000 and 4,000 feet so that if the engine stalled or there was any accident they could glide to shore. In crossing there was a gap of only about two [20] minutes when this would not be possible. They went with loaded gun in case they met or were overtaken by a Hun as they went within 20 or 30 miles of the lines. They could not fly too high for they might be taken for Huns and be shot at. Arriving in France they returned to England on “leave” boats, crossing from Boulogne to Folkstone, or by a Handley-Page airplane ferry which made regular trips twice a day over the channel with 16 passengers on board besides the pilot and baggage.50

With the Independent Air Force

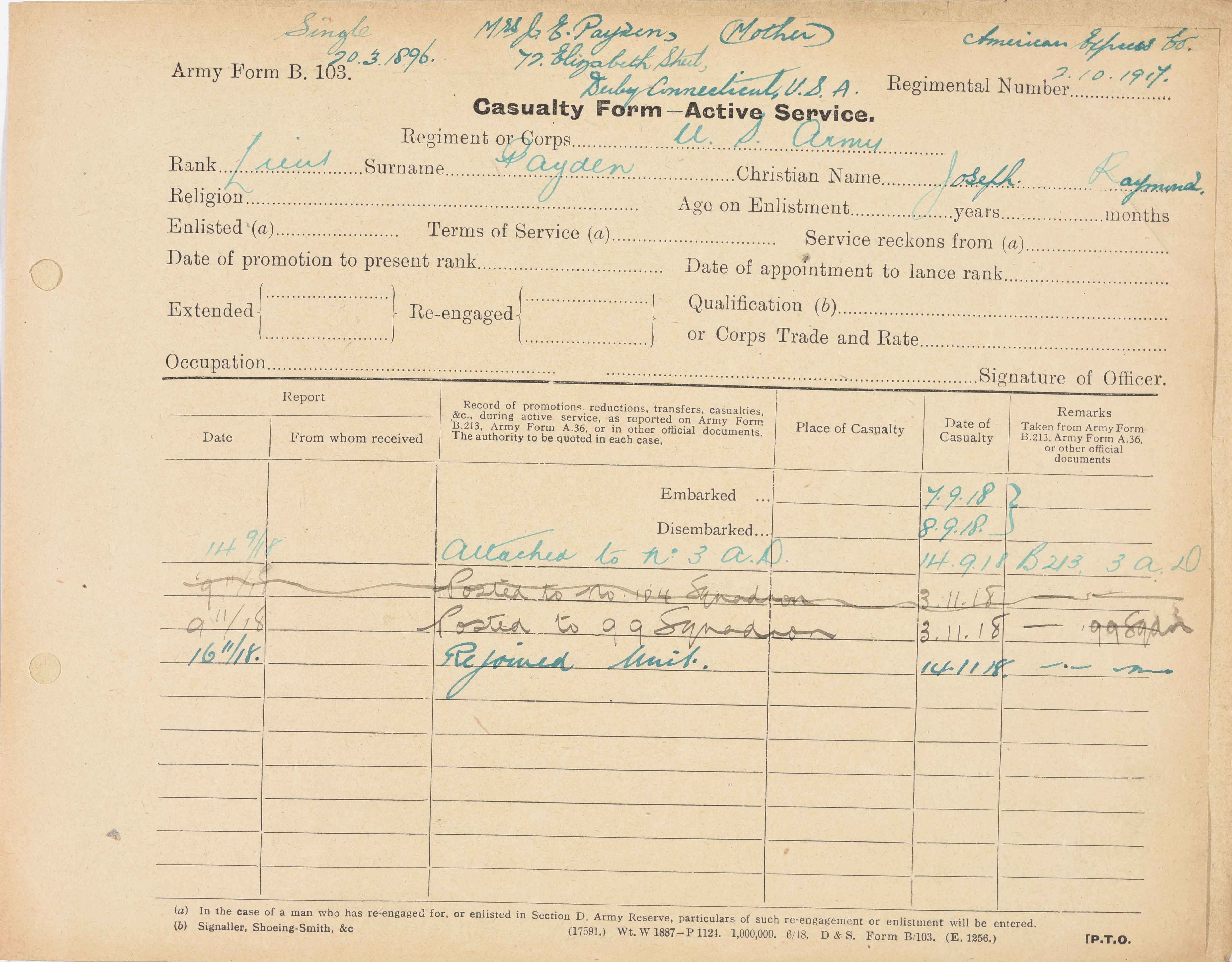

Payden’s and Wilcox’s assignments continued in tandem once they had completed a little over three weeks of ferrying duty. On September 7, 1918, they were assigned to the Independent Air Force.51 The I.A.F., commanded by Hugh Trenchard, was made up of R.A.F. day and night bombing squadrons, but operated independently of other forces (“neither under the orders of the Generalissimo [Ferdinand Foch] nor of Sir Douglas Haig,” as Maurice Baring put it52); it was tasked with long-range bombing of targets within Germany.53 The squadrons were stationed at various aerodromes south of Nancy (Ochey, Azelot, Xaffévillers and Roville-aux-Chênes), while Trenchard’s headquarters was somewhat farther southwest, at Autigny-la-Tour.54 (It is worth noting in passing that there were also Italian bomber squadrons in the vicinity—which accounts for the pictures of Caproni aircraft taken by Payden.55)

The two American pilots embarked for France on September 7, 1918, disembarking there the next day.56 What they did for the next six days is not clear, except insofar as some of the time must have been spent travelling across France to the Lorraine region. On September 14, 1918, both were assigned not to I.A.F. squadrons, but to No. 3 Aeroplane Supply Depot at Courban, about 125 miles southeast of Paris, and about eighty-five miles southwest of Nancy.57

As the number given to Courban’s A.S.D. indicates, the R.A.F. already had two depots where aircraft were assembled and issued. No.1, originally at St. Omer, was relocated during the German Spring Offensive to Marquise, where Wilcox and Payden would have delivered their planes while flying for the Central Despatch Pool. No. 2 had also been relocated, and was familiar to many American pilots in its location at Berck-sur-Mer. “The RAF depot at Courban was specifically created to supply the [I.A.F.] since the existing depots, located close to the Channel coast, were too distant to meet the organisation’s daily needs—notably the provision of replacement aircraft and aero-engines.”58

Once at No. 3 A.S.D., Wilcox and Payden assumed different duties: “it was then Lieut. Wilcox’s job to take machines to the front line squadron to replace casualties,”59 i.e., he continued ferrying duties, with the added danger of flying planes close to the front lines. Payden, on the other hand, became, according to his R.A.F. service record, a DH.9 test pilot.

It is unfortunate that there is no further or detailed information on Payden’s activities during the autumn of 1918: it would be of considerable interest to know exactly which planes he tested and how he went about it. His work at Courban apparently continued into early November 1918. On November 3, 1918, he, along with Wilcox, was reassigned to No. 99 Squadron R.A.F., which was stationed at Azelot.60 There is no record of either pilot flying missions with No. 99.61 Payden is unique among the members of the second Oxford detachment in having remained with the R.A.F. until the end of the war.

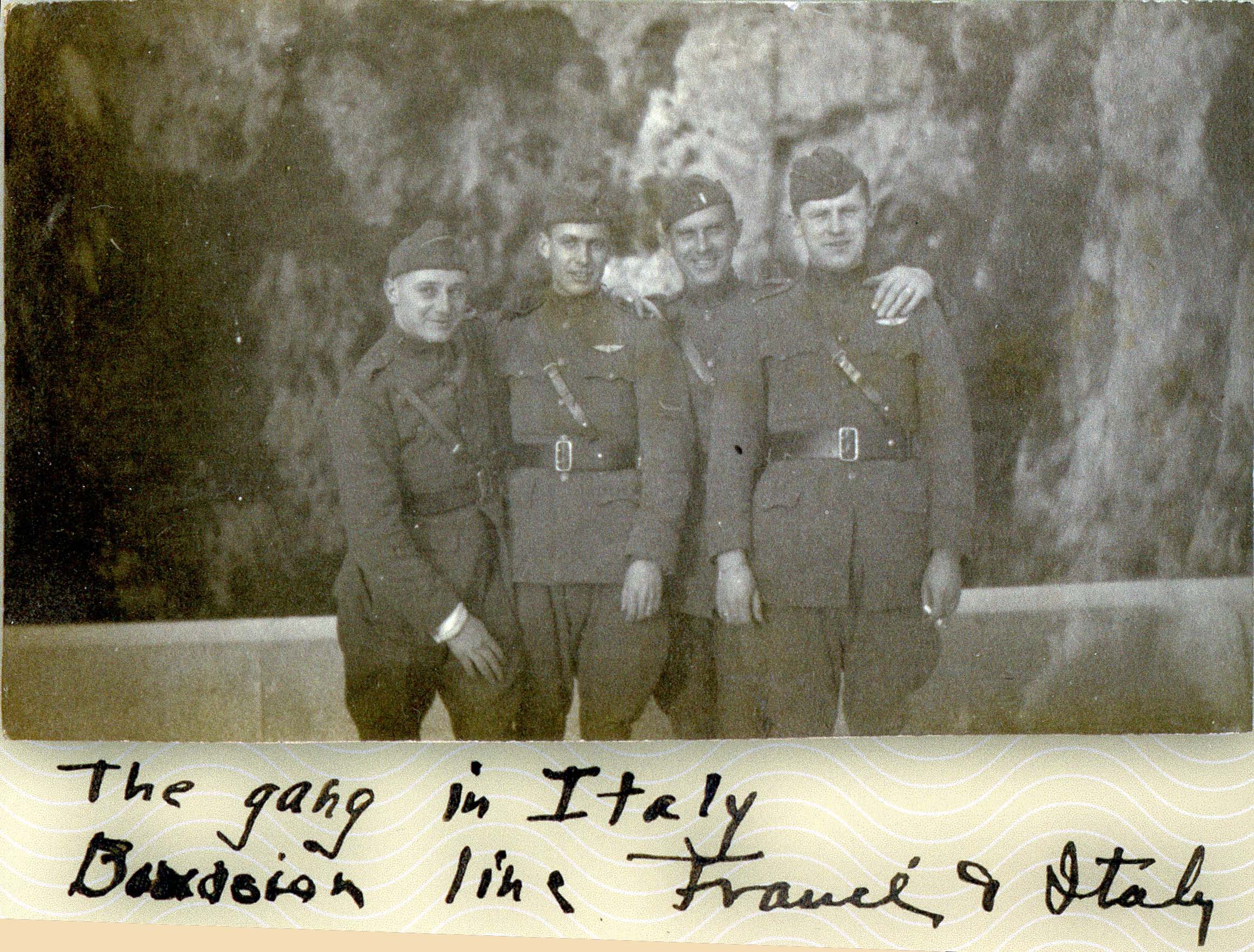

Three days after the armistice, both men “rejoined unit,” i.e., returned to the American forces.62 Payden’s friend Foss was assigned to the 2nd Aviation Instruction Center at Tours while awaiting orders home; Payden kept a Christmas 1918 dinner menu from Tours, which suggests he also was assigned there—unless he was simply visiting.63 Photos indicate that around the turn of the year, he, Wilcox, and fellow second Oxford detachment member Anker Christian Jensen (who had been with the U.S. 8th Aero Squadron and flying in the same general area as the I.A.F. squadrons), as well as Jensen’s observer, Arthur Paul Wilkinson, enjoyed time in southern France, Italy, and Monaco before returning to the U.S. 64

Wilcox was able to board a ship at Marseille at the end of January to return home. Jensen and Wilkinson left from Bordeaux in the latter part of February, but Payden had to wait another three weeks. On March 22, 1919, he began the voyage home on the Dirigo, which sailed from La Pallice, one of the ports associated with the U.S. Army embarkation camp at Bordeaux. The Dirigo, a Texas Company (Texaco) tanker that had been requisitioned by the United States for troop transport, dropped “anchor of Tompkinsville, N.Y.” on April 6, 1919, exactly two years after the U.S. entered the war.65 Payden returned to Sheffield Scientific School at Yale to complete his degree and then went to work for Union Carbide.66

mrsmcq October 27, 2021

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Payden’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for J Raymond Payden. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, California, Death Index, 1940–1997, record for Joseph R Payden. The photo of Payden is a detail from the full length portrait photo that serves as the frontispiece of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925. I am grateful to Joan Payden for a copy of this book and for her kind permission to use images from it.

2 Information about Payden’s descent and family are taken from documents available at Ancestry.com and from Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925, passim.

3 See copy of “Graduation Exercises of the Class of 1915 Derby High School” reproduced on p. 6 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925.

4 See Nettleton, Yale in the World War, vol. 2, p. 459.

5 Partially reproduced on pp. 7–8 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925.

6 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

7 See the account in War Birds, entry for October 22, 1917, as well as entries in the diaries of Barksdale, Deetjen, Grider, and Foss from around this time.

8 This according to the caption of a photo of Garver reproduced on p. 26 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925.

9 See the photos reproduced on pp. 25–27 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925.

10 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

11 See [Grider], Diary October 3, 1917 – February 7, 1918, entry for November 14, 1917, where there is a list of Grider’s hut mates; it does not include Fulford, but other entries indicate that Fulford was in the same hut.

12 Ibid., entry for November 8, 1917.

13 See Foss, diary entry for November 15, 1917.

14 Foss, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” (in Foss, Papers).

15 On No. 38 planes and locations, see p. 403 of Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force.

16 Sutherland and Canwell, Battle of Britain 1917, Chapter 9. (Sutherland and Canwell do not provide documentation, and I can find no record among casualty cards and casualty reports of this incident.)

17 Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925, pp. 43 and 38.

18 Ibid. p. 44.

19 On Payden’s assignment to No. 44 T.S., see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Joseph R. Payden.

20 Deetjen, diary entry for January 27, 1918.

21 Deetjen, diary entry for January 18, 1918.

22 Foss, diary entry for February 14, 1918.

23 Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925, pp. 31–32.

24 Clements, diary entry for January 30, 1918; Deetjen, diary entry for January 18, 1918; it is possible that their use of the term “Rumpty” did not distinguish between S.7s and S.11s. Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, include Shorthorns, but not Longhorns in their lists of planes available at Waddington training squadrons.

25 Deetjen, diary entry for January 18, 1918.

26 “Leaving Soon on Tour of World.” For details of this raid, see Castle, Zeppelin Raids, Gothas and ‘Giants’.

27 See Deetjen, diary entries for February 25 and 28, and March 5, 1918; Foss, R.F.C. Training Transfer Card; and McCarthy, R.F.C. Training Transfer Card.

28 Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925, p. 44. The voucher is for the most direct route from Winchester to Waddington—there is no indication of whether Payden had been in Hampshire for business or pleasure.

29 Cablegram 874-S.

30 Cablegram 726-S.

31 Cablegram 955-R.

32 Cablegram 874-S.

33 Cablegram 1303-R..

34 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 147.”

35 I should note that I have only seen digital images of Foss’s log book and that without examining the original I cannot rule out the possibility that pages are missing.

36 “Payden Has Seen Much of England.”

37 The photo is reproduced on p. 41 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925.

38 Reproduced on p. 43 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925.

39 Biddle, “Special Orders No. 116.” On the changing number, naming, and remit of the school at Marske, see Jefford, Observers and Navigators, p. 51. I suspect that the account in “Leaving Soon on Tour of World” is in error in reporting that Payden “was sent to an aerial gunnery school in Scotland.” However, photos on p. 34 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925 suggest he may have visited Scotland and Turnberry.

40 See Coates’s and Foss’s Pilot’s Flying Log Books.

41 “Life of an Aviator as Experienced by Lieut. Wilcox.”

42 See Ancestry.com, Connecticut, U.S., Military Questionnaires, 1919-1920, record for Edward Milton Wilcox; Payden’s postings paralleled Wilcox’s during this period. There should also be a Connecticut questionnaire for Payden, but I do not find it.

43 Jeffords, Observers and Navigators, p. 369.

44 “Life of an Aviator as Experienced by Lieut. Wilcox” (text in brackets is my best guess at missing portions of article).

45 Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Trainig and Support Units, p. 339.

46 Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 243.

47 Reproduced on p. 43 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925.

48 See Ancestry.com, Connecticut, U.S., Military Questionnaires, 1919-1920, record for Edward Milton Wilcox

49 See Ancestry.com, Connecticut, U.S., Military Questionnaires, 1919-1920, record for Edward Milton Wilcox; also Payden’s “Special Emergency [ration] Card,” reproduced on p. 43 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925, which indicates his “duty” began August 14, 1918.

50 “Life of an Aviator as Experienced by Lieut. Wilcox.” Where “gap of only about two minutes” is printed, in the copy available to me, “two” has been crossed out and corrected by hand to “20.”

51 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Joseph R. Payden; and “American Fliers with the I.A.F.,” which gives September 7, 1918, as the date of assignment to the I.A.F. for both of them.

52 Baring, R.F.C. H.Q., p. 272.

53 There is considerable controversy surrounding the I.A.F. Chapter 11 of Wise’s Canadian Airmen and the First World War provides an account and an assessment based on original documents that is worth reading.

54 See relevant entries in Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, on the squadron stations. See Baring, R.F.C. H.Q., 1914-1918, p. 277, regarding I.A.F. headquarters.

55 “I Caproni sul fronte francese e le esportazioni.” See pp. 55 and 58 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925, for photos of Capronis.

56 See “Lieut. Joseph Raymond Payden US Army” and “Lieut. Edward Milton Wilcox U. S Army.”

57 See casualty forms cited in preceding note.

58 Dye, Austin, and Davis, “The Gazetteer of British Flying Sites.”

59 “Life of an Aviator as Experienced by Lieut. Wilcox.”

60 “Lieut. Joseph Raymond Payden US Army” and “Lieut. Edward Milton Wilcox U. S Army.”

61 See the relevant entries in Rennles, Independent Force.

62 “Lieut. Joseph Raymond Payden US Army” and “Lieut. Edward Milton Wilcox U. S Army.”

63 The menu is reproduced on p. 38 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925.

64 See pp. 67–68 of Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925.

65 “Departmental News,” pp. 11–12; Colton, “Texas Steamship Company”; Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Joseph R Payden.

66 Payden and Payden, J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915–1925, passim.